Chapter Six. How to build great teams

So, you’ve got your Big Idea—you know what the business is for and why customers might want a piece of that. Now it’s the exciting part—shaping a team that can deliver on that Big Idea. First task is to plan to make that team a happy one ...

Happy teams make you more money. The best customer service is delivered by happy, motivated people. You cannot be a great modern retail business without happy and motivated teams. The best performance improvement strategy I could ever recommend is “make your team happy.”

A happy team of friendly motivated people, pulling together, having fun with customers, bristling with ideas and enthusiasm, people with passion for the job, can build huge performance improvements. Like so much in retail, the recommendation to create a happy team is very, very obvious, but is also a massive challenge. The best of us still struggle to get every new hire right, to always make the best decision in a given situation, to not drop the ball when the going gets tough. Management is hard to do right—that is why business rates good managers so highly.

Because managing people is hard, great teams are still the exceptions rather than the rule. That’s actually a good thing for you. Think of it as competitive advantage through team building.

A consistency I’ve seen through great retail businesses is that they understand their Big Idea, tend to be very clear on what the business is trying to do (mission), allow people to behave like grown-ups (respect) and are very good at recognizing positive behaviors (recognition). Let’s call these three things “cornerstones”: Mission, Respect, Recognition. Wherever the three are in evidence, great team and store cultures emerge and I firmly believe that this is a bit of a secret, if there is such a thing, of great leadership:

Cornerstone 1 Mission: We understand what we want to do for our customers.

Cornerstone 2 Respect: We make sure our people know they are empowered to do those things.

Cornerstone 3 Recognition: We reinforce those positive things by recognizing them when they happen.

The three then exist as a self-reinforcing loop: the clearer we are about what our business is for and the better we enable our people to do those things, and the more we notice and say “thank you” when they do them, then the better we become.

I’ll go into each cornerstone in more detail over the next few pages but first I want to illustrate the value and importance of a great store culture. I would also like to show you that your individual store culture can still be a great one even if the wider company culture isn’t.

Leadership

Things get a little bit tricky when we start to think about leadership and teams. I have a heartfelt belief that leadership cannot be taught—indeed we once lost out on a large bit of consultancy business because I fundamentally disagreed with the notion that leadership could be taught: A UK retailer with 1300 stores was looking to improve store cultures and was very proud of the expensive leadership program they had pushed 1300 managers through. But when we peeled back the detail of what had actually happened, it became clear that any gains they’d seen as a result of this leadership program were pretty much down to the fact that those 1300 managers had spent two days out of their stores and were hyper-aware that senior people were watching them like hawks post-course. It was also clear that those gains would evaporate quite quickly. And here’s where we lost the relationship: I’m not sure that the role of Human Resources is to teach a fundamental in-the-genes skill such as leadership. No, I believe its job is to find the best existing 1300 leaders out there within the total 48,000-strong workforce and then to put those natural leaders in the right roles. Pointing that out led to a huge disconnect from that particular client and we’ve not been back since. When I say “disconnect” I do, of course, mean “hissy fit”; as expected, their leadership program didn’t work and this company has experienced flat or declining performance in the seven years since I first wrote about them. I don’t want to be crowing “I told you so”—that doesn’t generate invoices—but, well, “I told you so.”

So, do you have to be a good leader to be a great retailer? Do you have to be a good leader to create a strong store culture? The painful answer is that to a large degree, yes, you do. You might want to do a bit of soul-searching for a moment on that. It might help if I define leadership—it’s really about answering one question: Are you able to inspire others to line up behind your chosen course of action?

Now—having got you through that (I’m hoping you answered “yes”), we get to the notion that great leaders can, and sometimes do, still fall on their behinds. Being able to lead is essential to the job at hand, but understanding where to lead and how to structure the journey is essential too. And that’s where your Mission–Respect–Recognition cornerstones come in handy; it’s like a leadership map: Follow those steps and you’ll get to where you want to go.

Let’s look at why it’s worth making a great store culture one of your destinations.

Why bother building a great team?

Improved customer service

Customers prefer to be served by happy friendly people—every observational study proves that conclusively. Tied in to improvements in employee retention (see p. 38) are corresponding improvements in employee effectiveness and knowledge. People who stay with you longer tend to get better at their jobs and that filters through directly to the customer experience.

• Customers come back more often and they rave about you.

Customers prefer to be served by happy friendly people—every observational study proves that conclusively.

• Customers return to stores that feel good to be in—the “people” part of a store is critical to that feeling.

• Customers share their great experiences, most of which relate to how your people have looked after them.

Cost savings

• Reduced shrinkage—happy people don’t steal from you and they care more about reducing customer theft as well

• Reduced employee turnover—happy people, and people who feel valued, stay with you longer and that means savings not only on advertising for replacements but also savings on training and your time.

Walking the talk

We cover values and mission statements later (don’t yawn, we’re talking practical advice, not management consultant waffle), when I’ll explain why these are so important to the success of your business. A great store culture makes an excellent starting point for making values and mission statements really work for you. Walking the talk also means that new ideas tend to be adopted more readily and more happily by the team: Everybody is up for driving the team forwards.

Support

You could create a happy team by letting everyone run riot, throw parties whenever they want, and help themselves to whatever they fancy from the stockroom. That of course wouldn’t do anything for the performance of the business. A great store culture still encompasses the unpleasant things such as firing people who don’t make the grade and reprimanding staff when they let the team down. However, if you have that great culture built and you have a happy team, they will tend to be far more supportive of you in those difficult decisions. That’s useful because it helps keep the disruption of such moments down to a minimum and the team gets over it more quickly.

Enjoyment

Happy teams are nicer to work within. Fun is a powerful component in a high-performing team. Shopping is in itself fun: In all but a few circumstances, customers like getting to go out and buy stuff so it’s reasonable to aim for a fun store culture too.

Reasons not to?

A lot of managers say “the company culture is so awful that I can’t make a difference here in my store.” Although I’m sympathetic to the additional pressure a bad company culture puts on its store managers, I can’t accept this as a real excuse to avoid building a great store culture. Retail superstar Julian Richer has this to say about the ability of a store manager to lead culture in their own store: “The culture of the store is determined by the manager and then we try to get our company culture on top of that.” It’s managers who create the store culture, not head office.

Why assistant managers must become “keepers” of the culture

Richer also remarked that “it is sad whenever a store manager leaves.” It is indeed sad when a great store manager leaves, and it can often mean the death of a team. This is why store managers should work closely with their assistant managers in planning and building a great culture. Aim to leave a little bit of yourself behind so that whoever takes over, ideally your assistant store manager, can strengthen the culture further, building on your work. For most of us, and I include myself in this, there is massive pleasure to be had from discovering that something you helped build is still solid and in play years later.

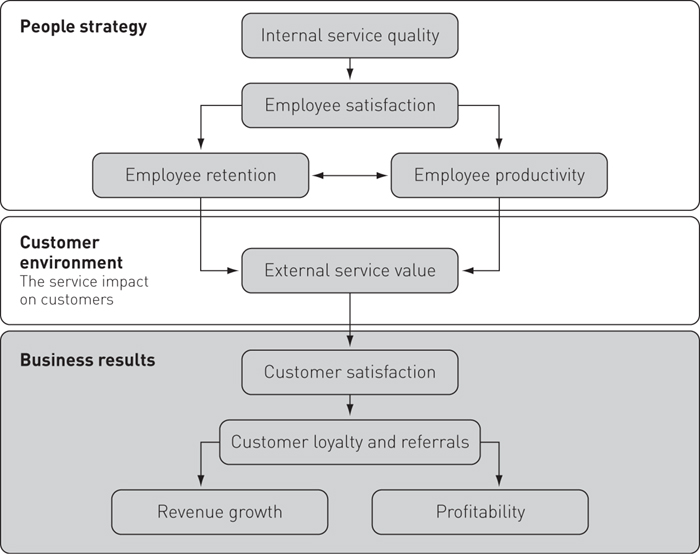

Service Profit Chain

I’m not keen on theory for its own sake and I get irritated by diagrams that have more to do with consultants trying to be clever than making a clear point, and that’s why there’s just the one diagram in the whole of this book. It’s a pretty important one though—some years ago, I was introduced to the basic idea that within retail and service organizations, it’s employees who have the biggest impact on customers” experience of the brand. Sounds obvious when you put it like that, and it’s true. What Service Profit Chain theory does is turn the fluffy bit of that equation into a way to measure the pound-note impact of treating your employees with respect, care, and integrity.

“Nice” means profit.

Source: Smart Circle Limited

Let’s step through those boxes then:

Internal service quality

• Treating your people well is good.

Employee satisfaction

• Because happy, motivated, and respected staff are more satisfied.

Employee retention

• They stay longer with you.

Employee productivity

• They get better at their jobs.

External service value

• And happy, stable, and productive teams tend to deliver the best customer service experiences.

• Which makes customers happy.

Customer loyalty and referrals

• And they come back more often, spend more money with you, and they recommend you to their pals.

Revenue growth

• Which means you stuff your registers with wads of cash.

Profitability

• Goes up and up and we all start to have baths filled with money instead of water.

And the thing is, the logic of this process is inescapable and can be seen at work inside the world’s best retailers—yet it’s rarer than it should be. Putting Misson, Respect, and Recognition at the heart of your management style will deliver this good stuff. Great employment experiences drive great customer experiences and that probably equals promotions all around.

The three cornerstones

Let’s just recap on those three cornerstones I mentioned earlier:

Cornerstone 1: Mission

We understand what we want to do for our customers.

Cornerstone 2: Respect

We make sure our people know they are empowered to do those things.

Cornerstone 3: Recognition

We reinforce those positive things by recognizing them when they happen.

So now on to the detail!

Values

This is another area where a lot of awful trash has been spouted by management gurus. It means that talking about values can feel a little ridiculous. This is a shame because a set of defined values becomes the practical tool that helps you to apply the mission statement to the everyday running of the store. Where the mission statement tells you what the company does, the values tell you how it wants to go about doing it. They are a reflection of what the company stands for. We’re talking about a list of words such as innovative, fun, honest, and inspirational. The trick is to mold these values into a set of practical sentences that tell us how to apply the values to the jobs we do every day.

A great way to think about values is to fix in your mind the perfect customer experience in your store, then imagine talking to that customer outside afterwards; what five emotions might they tell you they felt during that experience? Write down that list of emotions and then ask yourself this question: If my customers leave my store feeling those five things—are they likely to come back again? If the answer is “yes” then you’re on to something good.

Walking the talk

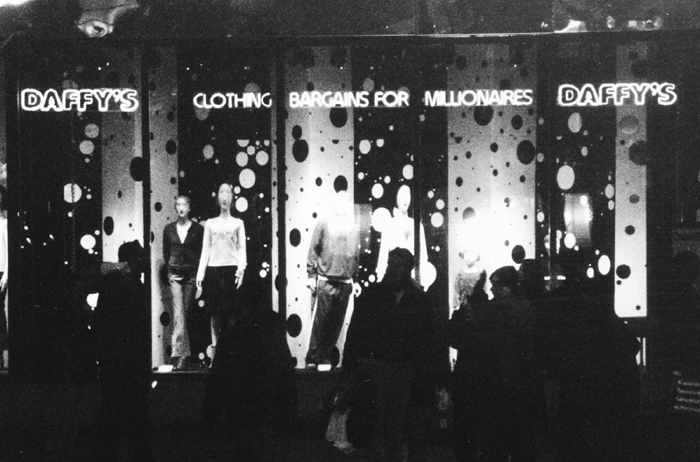

Defining a good mission statement and then living the values in-store—”walking the talk”—is good for you because it improves the customer experience and builds stronger teams; this in turn increases business performance. In a case such as the Best Buy one, walking the talk in store is doubly powerful because everything the central team does, such as advertising, promotions, and store investment, is also right in line with the mission and values. They strengthen each other.

Big Idea and mission perfectly expressed right there.

Source: Koworld

If you work in a business that has a clear and consistent set of values, use them to your advantage. Live and breathe them: “walk the talk” will improve performance. In an independent store, you too must define a mission and a set of values—everything else flows from them.

A good set of mission and values reads naturally: It uses language that a normal person can easily make sense of. Simple things—strongly stated.

Street Time

Now that you’ve read about Big Ideas, Mission, and Values—please have a look at the Street Time tool in Appendix III. As well as being good fun to do, it’s something that will help you to go out and find many ways to improve and change your businesses.

A disrespectful market

The mobile-phone retail business enjoyed, or suffered, a yo-yo sales curve during the 1990s and into the 2000s. Excellent businesses such as Carphone Warehouse (CPW) were not immune when the market first dipped sharply. But when picture messaging and color-screen phones (wow, sounds like the sort of phone my Grandad would have used) helped re-ignite the market, CPW benefited more than most. Carphone Warehouse is the honest phone retailer that emerged out of a time when the sector was dominated by sharks and cowboys. This is a retailer that prides itself on looking after everybody’s needs: customers and staff alike. It is a retailer whose successful employment policy is built on respect. It is also a retailer that has benefited from the very positive knock-on effects of such a policy.

Talk to an employee of CPW and they will tell you that the work is hard, the hours long, and the standards are stretching and rigorously applied. They will also tell you that they enjoy it enormously. Push a little harder: ask them “Why do you enjoy it here?” A consistent story emerges:

• “We get treated with respect.”

• “I’m trained so well that I never look stupid in front of customers.”

• “My ideas are worth something.”

• “I’m allowed, no I’m encouraged, to use my brain.”

• “It’s made clear that I can have a proper career at Carphone Warehouse if I want one.”

So, now how are things for CPW? The company thrived, has pushed through another recession, and continues to lead with its principles of respect, fairness, and honesty intact. It’s no coincidence that they have also aligned themselves closely with another leader that is built on similar principles—CPW and Best Buy now have a number of joint ventures, including 50/50 ownership of Carphone Warehouse and Best Buy stores in Europe. Respect and honesty, it seems, pays.

An alternative approach can be seen in the same marketplace. Back in 2003, Phones 4u was featured in a fascinating TV documentary. In one now infamous scene, a manager was shown enjoying the dubious honor of receiving what could be considered as quietly threatening phone calls from the then millionaire chairman John Caudwell. These phone calls were to remind that manager that he had but one week to improve the numbers or face the sack. That’s a classic example of management by fear rather than management by respect. I asked Phones 4u at the time how they felt about the picture portrayed in that documentary. They told me the result had been an upsurge in job applications from people they called “real go-getters, the sort of people who respond to a bit of pressure.”

When I wrote the first edition of Smart Retail, I said I was keen to see how this attitude would pan out for customers over the long term. The short answer is that Carphone Warehouse ran away with the prize, John Caudwell sold Phones 4u (for a tidy profit, mind) and the business has spent the last seven years working hard to improve its customer service standards as well as improving the way it manages its people. And guess what—it’s working but perhaps too slowly to significantly dent Carphone Warehouse’s lead. Customers have long memories ...

Flight to quality

In a fast-growing market, where price and availability are the overriding considerations, many customers will happily buy from the cheapest outfit regardless of reputation. The situation then changes quickly when market conditions tighten and saturation is reached. In the slowdown, customers gravitate to quality, they think a little more carefully about what they want, and they look for reliable sources of good advice. Then, when things begin to pick up again, customers often stick with the new relationships they’ve formed. They value those relationships with retailers who have looked after them knowledgeably, honestly, and with a smile. More than that—in an era in which customers have lots of choice, they tend to vote with their feet and go where the best overall experiences are. Technically it’s called a “flight to quality”—which is jargon, but it’s jargon that makes sense.

We saw this in 2010 as the UK ground out of recession—sales at Waitrose, of Tesco’s “Finest” range, of premium brands such as Sony and L’Oréal all grew where lower mid-range brands saw shrinkage. Right now, being a retailer who has proven to be a provider of great customer experiences is showing real sales benefits: Customers get fed up with austerity shopping and, while still spending less overall, they start to put what they do spend into nice purchases: “We’ll have nice week at the seaside this year but then a big family adventure to the Caribbean next year—instead of our usual annual trips to Spain.”

The 1980s retail legacy

Back in the 1980s, there was a surge in consumer-spending. In the UK, this surge ran alongside unprecedented levels of unemployment—for some everything was rosy and for others desperate. A group of UK retailers became incredibly successful off the back of the surge but some chose to exploit their workforces, knowing that the threat of unemployment loomed large. With demand for fashion, food, and consumer goods outstripping supply at times, leading stores were able to sell almost everything they could present. The best of these looked after their staff well and saw background unemployment as a reason to be a good employer rather than a bad one. On the flip side were those retailers who saw people as disposable, an expendable resource to be bullied into line. Customers were blind to the effects of this as they scrambled over themselves to buy, buy, buy and so the bully-boy retailers got away with treating staff badly.

I started in-store in 1985 and witnessed the worst of this first-hand: a management style emerged, and it was called JFDI, or “just flipping do it” (you and I both know that I’ve changed one of those words to a print-friendly alternative). JFDI was anti-respect: It was all about conformity and subservience. I first entered retailing in the middle of these years and it was mean at times. Nasty even. It was an atmosphere that chewed people up, burnt them out, took advantage of job insecurity, and made some people’s lives a horrid experience.

But come the early 1990s and the boom and bust cycle was beginning to flatten; with that flattening came a calming in the rabid consumerism and large reductions in levels of unemployment—a longer-term sustainable prosperity was established. And something happened in the way people, especially in the UK, shopped: They became more discerning, as if the hangover of the 1980s was accompanied by an understanding that spending for the sake of spending wasn’t a great idea any more.

And customers appeared to begin to notice that those businesses run on the principles of JFDI weren’t nice places to shop. Customers aren’t stupid: They might not be able to define what it is that they notice in a JFDI-led store, but it does affect them.

This effect is just one very good reason to invest in and show respect for your staff. Forget even the straightforward cost benefits of keeping your staff longer; the simple reality is that teams built on respect and passion ultimately bring more profit into your business. Teams built on fear and unreasonable pressure do often create short-term sales gains but they always crack, and usually this happens very quickly. What is more, they leave customers feeling negative about their interaction with the brand and less inclined to ever come back again. In an age of real-time access to live sales numbers, it can be easy to fall back, under pressure, into a JFDI management style. Don’t. What your business gains today it will lose tomorrow and next week.

The respect deal

Respect, thankfully, is a two-way street. Yes, you will still have to deal with under-performing colleagues. Yes, you might find yourself having to exit people from your business. That is always hard to do but in a team that has been built on respect, you will have worked hard with that person to make things right. The people in your team will know that and will support your decisions rather than becoming unsettled by them.

We have that phrase “You have to earn respect”; well, in retail management that gets warped a little. You, as a manager, have to earn respect from your team, sure—but you must respect them from day one! People are always wary of change, which is why you will have to work hard to earn their respect. But this is not a mutual deal. Even before you first meet your team you have to respect them. If you didn’t, if you came into a new store with an attitude that said “I’m in charge and until I know you I am reserving my judgement,” then people tend to turn off.

Luckily, the most effective way to earn respect is to give it! If you systematically go about building trust, recognizing people’s contribution, sharing training and creating opportunities for personal growth, then you will build a strong successful team that likes and respects you. You will have gone a long way to building a brilliant culture.

For some great tips on how to build respect, read Chapter 5 which is on Motivation; I’ve listed a whole series of them there.

Ownership—the value of mistakes

Mistakes are great. Mistakes are brilliant—get on with making things happen, make mistakes and learn from them, and try more stuff.

People make mistakes when you let them make decisions. They get a lot right too. Being as close as they are to where the action is, your team is absolutely the best people to be making more decisions for the business.

And yet, providing local decision-making tools to individual stores is something that fills most retail directors with horror. It is easy to see how senior central management can get scared about letting their store managers loose. But all the evidence tells us that this is wrong. Wherever proper decision-making power has been delegated down to individual store teams, it has led to increased sales and profit. Yes, it has also, sometimes, resulted in more mistakes being made. But mistakes are only unlearned lessons. You make one, you learn from it, and you move on.

Maybe that sounds a little too much like a homespun philosophy but it also happens to be true. Think about the early careers of people like Richard Branson, bankrupt in his teens, or Ray Kroc, the genius behind McDonald’s, who had a string of mistakes, false starts, and lean times behind him when, at 62, he spotted the potential for franchised fast-food. Mistakes are made when you try something new, different, or difficult. Sure, you reduce your errors down to zero if you never try anything, but just see what happens to your business when you do that.

Please don’t make a fuss

One of the issues that makes recognition hard to do at first is a cultural one. The British are embarrassed by praise, we struggle to accept it. Indeed the most common response among British workers to receiving praise is to blush and to break eye contact. The strange parallel to that praise response is that we generally do not have the same problem when receiving criticism. When on the receiving end of criticism, most British workers will listen, if not always graciously, but they will listen. We all tend to have a system for receiving criticism, maybe not always a positive system but it is nonetheless a system. When it comes to receiving praise, although we really like the feeling, we are a little unsure of how to react.

There is also a crucial difference between the delivery of praise and of criticism. We tend to be specific when criticizing but only general when praising. It is this lack of clarity, I believe, that makes people so bad at giving and receiving praise. We give usefully specific criticism such as “the budget you did isn’t right, where are the print costs?” whereas praise would be vague, “nice work on the budget.” This is important because the whole point of praise and recognition is that we do it in such a way that recipients understand exactly what they did well so that they can repeat that behavior. In the budget example above, the person who has been criticized knows they have to now go and sort out the print costs. The other person, praised with the “nice work on the budget” comment has no idea why this budget was better than the last one, or what it was exactly that they ought to repeat to get some more praise next time. Better praise would have been “I like how you’ve laid out the budget. That’s going to make it easier for me to get it approved. Thanks.”

“Doing” recognition

“Little and often” is a brilliant management maxim. It’s absolutely perfect when applied to recognition. To make too much of a moment of praise can make everybody feel uncomfortable. It can even sometimes encourage resentment from the team toward whoever you have singled out for extra-double helpings of praise. You are not attempting to make an individual feel like they are God’s gift to retail. If the thing they’ve done is really special then by all means mention it at a team meeting. But for the rest of the time, the best way to “do” recognition is this: spot something good, mention it quickly, say “thank you,” and be specific.

The bad recognition-habits we managers get into, often because we’re embarrassed by praise, include: worrying about singling out individuals, delaying praise, over-blowing praise, concentrating on catching people getting it wrong, and the inability to be specific with our praise. Delaying praise reduces the effectiveness of recognition. Recognition works best when fresh.

Too many people build their management style around spotting staff making mistakes and then correcting the errors. If you are one of them, try catching people doing good things instead. Do that and you will quickly find that staff actively attempt to repeat those good things and that they look for more and more good things to do. Recognition taps into so many crucial psychological needs. The easy bit to accept is that recognition, done properly, makes people feel good.

It is nice also to link recognition to small rewards, but this isn’t at all critical. Study after study shows that the part employees actually value is that moment where their manager, or a colleague, or a customer, says “thank you for ...”

Behaviors

Although a good recognition habit is all about being spontaneous, saying “thank you” whenever you see the need, it helps to have in mind a list of the sorts of things that you will be looking out to give praise for. At the risk of sounding like I’ve been snacking on a jargon cookie, what you should be basing your recognition on are “observable positive behaviors.” Essentially that’s all the good stuff people do that you can spot them doing.

When you first decide to introduce recognition, putting together a list of these “observable positive behaviors” helps the whole team to get a handle on what it is that you are looking for. Once you’ve sat down and really thought about these behaviors, you can stick a list up on the noticeboard. Give a copy to new starters, and use it as a basis for review meetings.

“Observable” is the key word in this bit of jargon. It tells you that the behaviors you are looking for are those that you actually have to “see” happen. Sales is not an “observable positive behavior” because it is an activity that (a) you already measure closely in the performance numbers, and (b) you will be discussing the sales action with each member of the team anyway. How a person makes a sale though—that could easily include a positive observable behavior: going out of their way to find a bit of information for a customer, or selling an item that was right for the customer but that had a lower commission-rate on it for the salesperson.

Those “observable positive behaviors” that relate to helping make customers happy are important. With any luck, such behavior will show up as a sale, but even if it doesn’t, that customer has left the store with a good feeling about your business. That is worth its weight in gold but in a way that is very hard to see from looking just at the hard performance numbers.

Take a look at the “Great moments” section in Chapter 9 for a little set of illustrations of observable positive behaviors in action.

Easy ways to “do” recognition

There are two easy routes you can go down to build recognition into your team culture. Doing specific recognition needs to be learned, so don’t be embarrassed that it might not be part of your current style. You will get there by practice. Equally, don’t assume that because you do often say “thank you” that you are getting recognition right. I’ll lay down good money that, when you are honest with yourself, you will find that 90% of those “thank you” moments are non-specific.

In the years between the first edition and the one you’re reading now, loads of managers have fed back that this part of the book is the one they were most skeptical about but that once done had been the most rewarding. I guess I’m saying “disconnect the cynicism for a bit and give this stuff a go—you’ll be glad you did.”

Method one—The 20-second ceremony

Use a couple of team meetings to make up your team’s list of “observable positive behaviors.” A good way to get a great list together is to start with the Big Idea, the mission, and values too, and think about the kind of things you can do to support them.

Now make up some “thank you” notes. These should have space on for the recipient’s name and a bigger space for you to write down why you are pleased enough to want to say “thank you.” Print out a bunch of these and keep some in your pocket at all times. Whenever you see an opportunity to say “thank you,” fill one out quickly and go put it into the hand of the person you want to say “thanks” to. You don’t even have to say “thanks” if you don’t feel you can. You don’t have to make a song and dance of it, you don’t even have to speak if you feel uncomfortable. What is important is that the exchange of this note is something both of you understand: It tells the recipient that you have noticed and that you are pleased, nothing more, nothing less. Takes about 20 seconds to do.

Dish out blank “thank you” notes to the team as well. Encourage everyone to use these “thank you” notes. Workmates recognizing each other’s efforts has almost as much power as when you do it. You have really cracked it when you get customers to fill in “thank you” notes.

The 20-second ceremony works so well and is unobtrusive: I’ve seen this work successfully in a tiny KFC that was processing 50,000 lunch transactions a week. People really do respond to it. The notes can feel a bit silly at first but that soon goes and the process of recognition becomes part of the everyday team culture. You will never find a cheaper or more effective way in which to transform your team’s performance.

Method two—The Heroes Board

Allocate a piece of wall space to recognition. Make up some “thank-you” notes similar to the ones mentioned above. Start giving them to people under the same criteria, and tell recipients to hang them up on the wall. This method introduces a little bit of peer pressure because everyone can see who is being praised, but you might find it more comfortable for you than recognition method one.

In both methods, you can use the best examples to determine what you do with your non-cash rewards (which we go through in Chapter 5). It’s quite nice to build in a little focus at team meetings for recognition. It’s even more effective to use one such meeting, each week, for a little bit of extra recognition. Take the best “thank you” or “hero” example from that week and give the person a decent bottle of wine, a case of beer, flowers, or good chocolates. Not too much, but it feels great to receive, and it really sets the scene for a rousing and effective team meeting.

Why recognition works

Why does specific recognition like that work so powerfully? It’s about clarity: You say to somebody “Well done, good job today” and it feels good to that person for a bit, but when they later ask themselves “What did I do different that meant I got praise today?” it’s difficult to actually know for sure. When instead you say “Well done, thanks—you’ve made that new person feel welcome and I appreciate it, helps to bring us closer as a team” that staff member walks away knowing exactly what behaviors to repeat in order to get nice praise again.