7. Shopper Models

Retail Marketing Definition

We subscribe to the definition of retail marketing as “all the activity that occurs approaching, within, and exiting retail locations.”1

Marketing at retail takes three forms:

• Branded manufacturers branding, marketing, and selling their products at retail

• Retailers branding, marketing, and selling their private-label products in their stores

• Retailers branding and marketing their stores in the general marketplace

Brands need retailers for the distribution they provide; retailers need brands to support the statements they want to make with their store’s positioning against other retail competitors and to drive category traffic. Even while brands are helping retailers with their positioning and the improvement of category results, retailers work to increase the share of private-label sales at the expense of the brands with whom they “partner.”

The job of all retail marketers is to leverage conscious and subconscious shopper behavior to improve results. The macro trends affecting retail create a newly empowered shopper operating within a hypercompetitive retail environment. Winning marketers must combine an understanding of what the shopper does and why she does it to design the optimal retail solutions that deliver superior results.

Shopper Understanding

The cognitive and behavioral research on shopper behavior focuses on information processing and decision making. This research can be broken into four general groupings according to the operative behavior drivers studied:

• Cognitive

• Logical

• Social

• Biologic

Cognitive studies focus on the subconscious use of schemata we employ to help us navigate a world that would otherwise quickly overwhelm us. Logical studies concentrate on the way we apply an analytical approach to completing our shopping missions, whereas social studies focus on the role groups play in driving our shopping decisions. Biologic studies center on the hard-wired elements of the brain at work in the way we process information and make decisions as tracked through neural mapping. Because we are such complex creatures, it is our view that all four elements work in concert to influence behavior in stores.

Cognitive Research

The application of cognitive research to retail marketing begins with an acknowledgment that today’s retail stores are too complex to deal with on a strictly rational level. A typical grocery store contains 30,000 SKUs supported, in the stores MARI measured, by 9,378 pieces of marketing material. If we spent just one-half second on each item or message option presented, we would be in the store for 55 hours. To deal with the complexity we face at retail and in the world in general, we need tools for simplification and improved efficiency. From an information processing standpoint, we employ selective perception and schemata to maintain our equilibrium and to operate effectively within a world that would otherwise overwhelm us. The example in Figure 7.1 illustrates some of the tools we all use to process information. It has been used to great effect by Dr. Hugh Phillips of Phillips, Foster & Boucher in Canada to describe our approach to the retail experience.

Deselection

Mark your time with a timer and then look at Figure 7.1 and stop the time when you locate the black oval:2

There are 25 symbols in the illustration. If you spent even one-fourth of a second on each symbol, it would have taken you six and one-quarter seconds to complete the assigned task. If you are like most people, you were much more efficient than that because you used a shortcut to locate the black oval. You scanned the illustration in search of the desired object and stopped when you attained your goal. This behavior is analogous to our use of brands and signage to assists us in our efficient movement through a modern store.

Looking away from the figure, can you recall what symbol was to the right or left of the oval? Can you recall what was above or below? Again, unless you have Rain Man-like powers of observation and short-term memory recall, you likely can recall nothing other than the position of the oval. In addition to scanning to locate the targeted symbol, you deselected everything that did not fit the criteria. Either you did not see it, or you saw it and discarded it as irrelevant to the task at hand.

Psychologists refer to a related concept as “inattentional blindness.” The concept was forcefully demonstrated by Daniel Simons and Christopher Chabris in a study they conducted in the 15th-floor elevator lobby at Harvard University.3 They prepared videos of two teams, one dressed in white and the other dressed in black, passing a basketball back and forth. They recruited subjects and asked them to view the video and to count the number of successful passes completed by the team in white. In one version of the video, a woman dressed in a gorilla costume entered after 45 seconds and walked right through the scene. Although she is clearly visible for a full 5 seconds, 56 percent of all participants did not recall the appearance. In a second version of the tape, the costumed character stops, faces the camera, and pounds her chest before walking off. Even with this extremely disruptive behavior that lasted 9 seconds, 55 percent of the subjects did not recall the gorilla. The test subjects were so completely focused on completing their task that they screened out everything that was not relevant to that task. To break through this focus, the disruptive power of the interruption would have to be extraordinarily powerful. Compare this example of unintentional screening while processing information to the predominant number of marketing at retail executions that are never observed by shoppers.

Conscious Processing

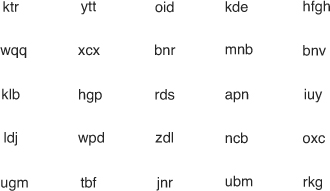

Borrowing another example from Hugh Phillips, look at Figure 7.2 for six seconds and look away after trying to remember as many groupings as possible:4

Figure 7.2 Conscious Processing

Most participants can remember fewer than seven of the groupings. As Hugh Phillips notes in The Power of Marketing at Retail, “the capacity of the attention span is surprisingly limited. Scientists measure the capacity of the attention span in terms of chunks—a chunk being a well-known word or phrase. Under laboratory conditions, it has been found to be around seven ‘chunks.’ However in the real world it is less.”5

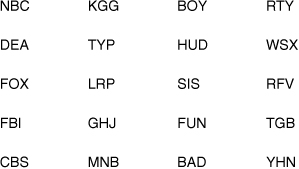

Try the experiment again with a second set of letter groupings in Figure 7.3.

Figure 7.3 Conscious Processing

If you were like most participants, you remembered more of the letter groupings because they were familiar to you. If you were quick and clever, perhaps you created a mnemonic scheme to help you remember more of the groupings. You might have found relations between groups such as three networks (NBC, CBS, FOX), federal government agencies (FBI, DEA, HUD), or created a story such as, “a BOY and his SIS had FUN being BAD.” If you did so, you were trying to increase your efficiency (the number of things you could remember) by decreasing the number of things that you had to recall. What is almost certain is that all the groupings you retained came from columns one and three and none from columns two and four. We all screen for the groupings that had meaning. It is hard work to use our conscious attention. We subconsciously look for ways to make our lives easier and fulfill our duties more efficiently by screening, seeking things that have meaning, and looking for patterns.

Selective Perception

What we observe is not necessarily what we see. Our brains deal with only a fraction of what we “see,” and we sometimes process information differently than the way it is presented. Optical illusions offer a prototypical illustration of selective image processing. In Figure 7.4, you see either a duck or a rabbit, depending on which elements you selectively process.6

Pattern and Structures

We use our mental capacity to identify meaning in the images we confront and establish an order in the world around us. To make this task easier, we employ an underlying organizational pattern or structure.7

Figure 7.4 Selective Perception

The utilization of these conceptual frameworks allows us to complete everyday tasks on a type of autopilot that does not make us work as hard and frees our conscious processing for other tasks. In the beginning, these shortcuts involve a conscious learning. Over time and through repetition, they become “second nature” and we perform these tasks automatically. Examples include any type of sporting endeavor pursued diligently over time, whether it is driving a golf ball, skiing downhill, or shooting a free throw.

One illustration is driving a car. When we first begin to drive, we consciously walk through all the behaviors—signaling, viewing the mirrors, gently merging into traffic, reading road signs, and so on. Over time, the routine tasks of driving require less conscious processing and our everyday commutes fall into regular patterns that do not actively engage our conscious processing. In the retail world, we all accept the basics of retailing that are routinely taught to new employees. We know the general layout of the stores, we expect to find certain items within defined categories, we expect sections to be blocked, and such. These shortcuts give us tools to navigate the complex store environment. Stores that fit our internal structures are “easy to shop” and will likely be revisited, all other things being equal. Those that do not fit the patterns are hard work and will fail. The Target store in Pasadena illustrates this phenomenon for us. The store is unusual in that it is one of the few multilevel stores in the chain. A few years ago, Target totally remodeled the store to make room for a food section. In doing so, they split the fashion merchandise on different floors so that, rather than having all the apparel in one location broken into children’s, men’s, and women’s sections, they had women’s apparel on the first floor and men’s and children’s clothing on the second. We logically understand the intent to link children’s apparel with toys, sporting goods, and seasonal merchandise, thereby achieving the adjacencies we would expect in a more typical layout. However, the layout so violently conflicts with our internal sense of the way it should be, we never feel comfortable, and always experience a sense of having to work to figure out where things will be in the store. Consequently, we actively work to avoid going to the store, and our visitation is less than half what it used to be before the re-merchandising. We offer this not as a condemnation of the store layout that may be successful, but only as an example of the impact of internal patterns on shopping.

Consistency

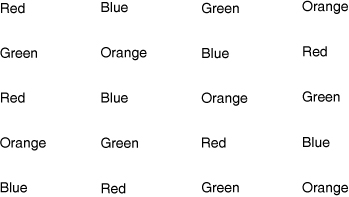

Let’s briefly visit one final sample from Roger Blackwell in an exercise that is typically run in large group settings.8 On a sheet of paper, write the words in Figure 7.5 with coloured pens so that the color matches the word. On a separate piece of paper, repeat this list with the colors for the letters that do not match the word, so that red is written in blue ink, green is in red ink, and so on.

Read the first list aloud.

Now repeat the process with the second set of words.

Typically, groups have no problem completing the first task. However, while groups generally start out correctly and in synch on the second chart, by the end of the first line execution starts to fail, and it totally disintegrates on the second line. What is happening is that when the words match the visuals, we process the information easily because it conforms to our expected norms. In the second example, the visuals do not match the verbal. We have to override the subconscious perception of color to complete the conscious processing of reading text. Our brains have to work hard to complete the task, and collectively we begin to fail early in the process. Compare this to your execution of marketing at retail material and the conformation to expected patterns for shoppers in the store.

Our brief examination of the application of research into how we process information illuminates five key points:

• Conscious processing is hard work and limited in scope. Consequently, we look for ways to increase our efficiency and ease our burdens.

• Information processing is deselective. We search for that which is relevant to our task at hand and exclude that which is not.

• What we “see” is different from what we observe, and our processing of information into meaningful segments is driven by a search for order that drives our interpretation and perception.

• We use patterns and structures to simplify complexity. Wherever possible, we move from a conscious consideration of every action to the employment of shortcuts to minimize our effort.

• Efficient processing breaks down when the conscious and subconscious do not synch. When our conscious processing does not match our subconscious expectation, our workload increases dramatically, we become fatigued, and performance deteriorates.

A recent personal experience for one of us highlights the application of many of these principles in the retail store. While preparing for a major holiday meal, I realized I did not have enough yeast for the planned amount of baking. I had already completed my major shopping trip to stock up for the meal. But, as typically happens, I needed to make a fill-in trip for the forgotten items and last-minute additions. My mental list was only five items, and my expectation was that I could complete my journey through the store in a few minutes. I grabbed a hand basket, picked up the first three items in produce, headed to the baking aisle, and stopped short. I could not find the yeast. I knew that the yeast was in this aisle because I shopped this store frequently. I knew that it was at eye level above the flour, and yet I could not find it; I could not find the empty hole to indicate it was out of stock, and I could not understand why I was having difficulty. I literally had to stop my anticipated pace of progress through the store and move consciously, item by item, across the shelf until I located the product. At last, after several painful seconds, I found my yeast and continued on.

Being immersed in the marketing at retail research, I naturally had to analyze what had occurred. For as long as I can remember, yeast had been packaged and merchandised in a horizontal package, as shown in Figure 7.6.

Without realizing what I was doing, I was deselecting everything on the shelf that did not have this shape. When I discovered the item for which I was searching, it looked like Figure 7.7 on the shelf.

Everything was the same, except the square packets of yeast had been stacked to create a vertically oriented rectangle instead of the horizontal pattern I had in mind. I had created a heuristic for yeast that was based on its uniquely horizontal orientation on the shelf and excluded all the other potential visual clues such as color, logo, and so on. I recognized the space optimization associated with a more efficient use of the cube and then immediately wondered if the category had lost sales while shoppers built new visual associations with the product.

The search for yeast had become a task similar to searching for Waldo in a cartoon. The challenge for all retail marketing participants is to avoid creating their own Where’s Waldo situations and, instead, define clear easy paths to find presentations, such as these in Figure 7.8.

Figure 7.8 Clearly Defined Sections

Logical

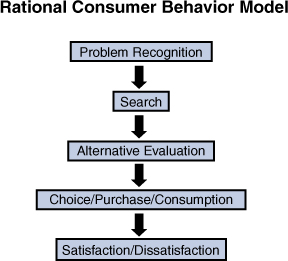

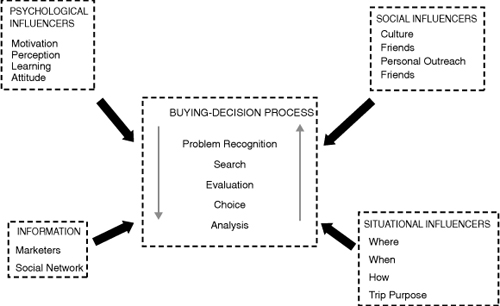

Although we all take shortcuts and respond to subconscious stimuli while in-store, the act of shopping is also a rational process. Roger Blackwell, formerly of The Ohio State University, published a number of studies that deal with the logical aspects of shopping. In general terms, as shoppers, we identify a problem, search for a solution to the problem, evaluate alternatives, and then make a choice. After consumption or use of the purchased product, we evaluate our satisfaction or dissatisfaction with our decision and incorporate that into our knowledge base for future evaluations (see Figure 7.9).9

Of course, as we work through this process, we are confronted with a tremendous amount of marketing at retail that tries to persuade us to choose option A over option B and to pick up items C, D, and E along the way.

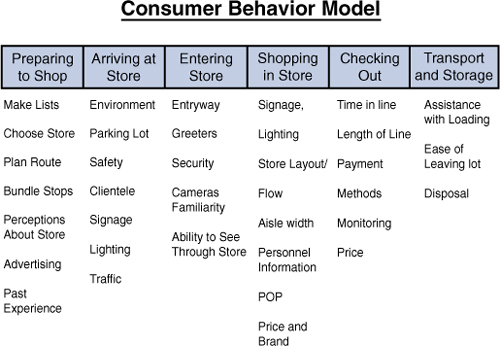

As Blackwell further dissects the logical aspects of a typical retail trip, we engage in groupings of behaviors. As we prepare to shop, we make lists and then decide which stores we will visit and the route we will take. We arrive at the store, and our experience is influenced by a host of influences including other shoppers, signage, traffic, parking ease, and more. As we continue into and through the store, our experience is affected by the people we meet and physical aspects of our journey. After our purchase decision is made, we continue to gather information and impressions formed by our experience in the process of checking out and exiting the shopping location. Together, these become part of our memory and play a role in our evaluation of alternatives when we are choosing a store in the future (see Figure 7.10).10

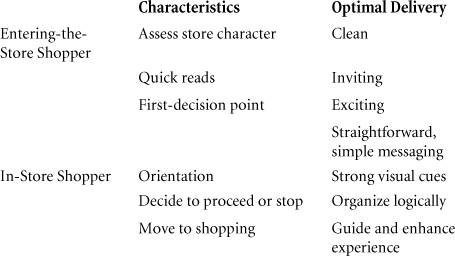

As we enter the store, we continue with a formal process of

![]()

Figure 7.10 Consumer Behavior Model

We repeat this process until our mission is complete and our eventual basket likely contains a mix of planned and unplanned purchases, unless we are fulfilling a specific task. In total, we choose a store and decide on a navigation of that store, during which we make product category, brand, and quantity choices. These items then combine to create a total shopping basket for this trip, as depicted in Figure 7.11.

Figure 7.11 The Shopping Process

For most retail marketers, the parking lot would not seem to be near the top of any marketing consideration. However, the research shows that shoppers evaluate this criterion, often subconsciously, in terms of availability of parking, safety, and ease of exit, and that these considerations have an impact on sales. On the negative side, shoppers avoid a lot that is in disrepair as signaling that the store cannot be well-ordered within; they will also avoid an undersized parking lot during peak periods because cars line up in the road to jostle for parking.

At the other extreme is an example one of us experienced on a visit to the Pick and Pay Hypermarket in Durban, South Africa. I had heard from our hosts about how the parking lot experience enhanced the overall shopping trip and wondered how, outside of the typical access to convenient parking, this could be possible.

Upon arriving at the store’s parking lot and much to my pleasant surprise, there was a uniformed greeter. He was not only welcoming me to the store, but he was also pointing me to a convenient parking space. He had the biggest, most sincere smile on his face, with one arm waving hello while the other pointed me to my spot. My immediate response was, if the store goes to this effort to make the shopper feel welcome outside of the store, I can only imagine the in-store experience. I was not disappointed and, for the first time, actually understood how an effort outside the location can affect perception of the inside of a store.

While making individual store selections, a number of other factors come into play, including

Weber’s Law—We evaluate things in relative versus absolute terms so that differences between options must be large enough to matter to us before they influence us to change our behavior.

Adaptation level theory—We evaluate stimuli relative to the existing knowledge we have.

Perceived risk—We compare the level of uncertainty about performance against the consequences of poor performance.

Personal accounting—We incorporate our perception of losses versus gains on our internal scorecard.

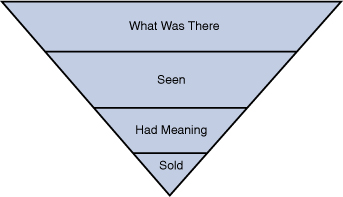

Throughout our search for and acquisition of products, we move through an environment in which many more stimuli are presented than are seen; of those that are seen, fewer have meaning; of those that have meaning, even fewer result in a sale (see Figure 7.12).

As we process the store environment, we loathe dissonance and will go to great lengths to make things consistent in our minds. We search for experiences in tune with our expectations within the stores we select; we filter messages aggressively; we utilize the information we have; we weigh the risks and rewards; and, after taking action, justify our decisions and purchases while maintaining a personal scorecard.

With an understanding of logical shopper behavior as shoppers move through the store and fulfill their shopping goals, we can optimize our efforts:

Social

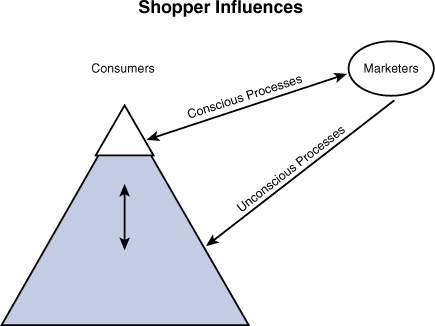

Expanding our area of focus, we now consider the role of social forces on the shopping process. As we have seen both in the previously cited studies and the field research in stores, the way shoppers make decisions is multilayered, and the relationship between consumers and marketers is complex. The communication between the two occurs at both conscious and subconscious levels with the weight of the subconscious far surpassing the conscious. Figure 7.13 depicts the relationship between shoppers and marketers:

Figure 7.13 Shopper Influences

This process involves our attitudes, including the way we feel about a store or product, our intentions relative to the available shopping options, and our beliefs. Social forces play a significant role in shaping the attitudes that affect behavior. Although we have an ostensibly logical process for acquiring the products we want, it is influenced not only by the way we process information but also by social and group forces (see Figure 7.14).

As we move through the preceding elements, social and group forces work to mold our state of mind before shopping, while they also directly affect our actions at retail. For a reference point on the impact of social or reference groups, consider the persuasive power of the groups to which we belong in shaping our perception of what is hot or cool, or even necessary. Likewise, it is easy to observe the impact of a child on the items that end up in the shopping basket and the total basket size, or the power of a tightly knit clique of teenagers in driving actions in a Saturday trip to the mall.

Social factors also play a role in our collection and processing of data. Beyond the information that retailers and manufacturers create and deliver, consumers and shoppers also seek data from social sources. These may be delivered on-line, in traditional media, or in person. The careful cultivation of early technology adopters for electronics, or rap stars and basketball players for the launch of the Cadillac Escalade, serve as witness to the social role in information gathering. Self-referential groups can remain relatively constant as they do for preteens or shift depending on the considered area; that is, geek friends for technology, music aficionados for music, and so on.

Finally, situational factors work to guide our decisions on why, where, when, and how we buy. These situational factors could be societal, like the chilling effect of a market recession on our willingness to make large purchases even though our individual purchasing capacity is not at risk. Or the factors could relate to a small group or individual. Our central point is that attitudes before we enter the store, our consumption of information, and our approach to shopping are influenced by a set of social influences that combine megatrends with self-composed reference groups.

As we assimilate these social influences, we tend to respond and pay attention to things that reinforce our world view and filter out the things that do not fit with that view. We remember things with personal significance, things that are consistent with our views of the world, and things that have either important consequences or associations.

We form perceptions of ourselves by observing our own behavior: “If I took this action, it must be rational.” We evaluate choices with the available knowledge, but that information base extends beyond personal history and data points such as price references and brand imagery presented in stores to include social endorsements. Social forces shape our attitudes and choices of stores, brands, and products. In stores, these social forces can influence product selection, impulse buying, and brand switching. At the same time, situational factors affect our logical/economic shopping decisions and choices at all levels.

Consistency Versus Boredom

When we shop, we seek comfort in consistency and familiarity. However, a potential conflict arising in that sameness can breed boredom that can result in a loss of impulse sales as everything except the necessary is excluded from consideration. Shopping on autopilot provides a sense of comfort, but shoppers tend to not see anything outside of the mental list they are using to shop. Interrupting the autopilot creates dissonance.

This dissonance causes shoppers to “see” new things, opening them for purchase consideration at the same time that it causes stress by injecting thought into the shopping process. To optimize results, we need to balance the artful interruption of the shopping experience with the consistency shoppers expect.

Biologic Research

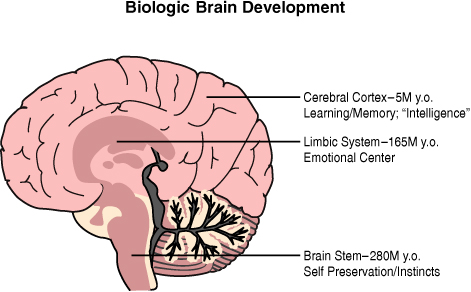

The biologic studies begin with the development of the brain over 280 million years of evolution. The team at ShopConsult, a German company that is a leader in the field, links the brain’s development with its larger role in decision making. The brain stem, which is roughly 280 million years old, is our instinctual center and the locus of self-preservation behavior. The limbic system is our emotional center and dates to 165 million years ago. The center of “intelligence” or learning and memory is the cerebral cortex, which weighs in at a youthful 5 million years in age (see Figure 7.15).11

Figure 7.15 Biologic Brain Development

By studying the neurological reactions to stimuli, the researchers can identify primary, secondary, and tertiary response levels. At the primary level we focus on safety and our base needs of food, sex, and shelter. This would describe the dominant operating system under times of deprivation or distress, where all other concerns shut down. A more standard level of operating in North America and the developed world has us moving through life at a social level in which we seek interaction and our limbic system is active. At peak performance levels, we seek discovery through physical or mental challenges that demand the processing of our cerebral cortex.

Our response to visual stimulation, likewise, triggers activity in different parts of the brain as we move from safety to social and discovery considerations. Negative or pain avoidance imagery triggers a reaction in the brain system, whereas social events activate the limbic system, and aspirational personal achievement stimulates the cerebral cortex.

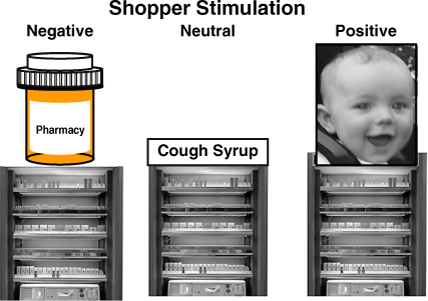

Applying this learning to in-store marketing, the imagery used in display presentations triggers a variety of responses that create an emotional link to the brand and affect purchase. Consider the different options presented here: the depiction of a spoonful of medicine posed next to a professional physician-like bottle of elixir, as opposed to the display with no picture but just a category description, and then the presentation of a healthy baby. In the examples in Figure 7.16, the medicine is a means to an end—the way to achieve the smiling health of the last picture. The negative image of a bottle of medicine works against the brain stem, whereas the positive imagery of the happy infant activates the more developed regions of the brain.

Figure 7.16 Shopper Stimulation

Summary

Moving beyond the field research that measured shopper’s actions in-store with great precision, we reviewed some of the key academic research that applies to the shaping of shopper attitudes and behavior in stores. The research is broken into four categories:

• Cognitive—A review of the way we process information in general that applies directly to our collective and almost universal approach to dealing with the tremendous number of choices and messages we confront in a typical retail store.

• Logical—The task solution approach to the fulfillment of our product needs. This approach is related to classic economic theory that holds that all purchase decisions will be rationally based on our personal completion of a value equation for each choice (value = quality / cost).

• Social—A consideration of the interconnected relationships that shape our attitudes and behaviors in stores, affect our choice of credible information sources, and influence our decision on whether we should purchase and how we should purchase.

• Biologic—An evolutionary look at the underlying basis for our reaction to stimuli in the market that is influenced heavily by our need state while shopping.

Together, the academic research helps us understand the “why” behind the “what” that occurs in store. We know that a small fraction of the marketing material presented at retail is seen by the shopper. We now can understand how the advertising we present must work against the four areas of human psychology to be effective.

Endnotes

1. Roger Blackwell, Retail Marketing, Orlando, FL (2003).

2. Hugh Phillips http://www.instore-research.com/Images/Hugh%20PFB%20Presentation1.pdf, page 9.

3. Christopher Chabris and Ben Sherwood, What it Takes to Survive (New York: Crown Publishing, 2010) http://www.newsweek.com/2009/01/23/what-it-takes-to-survive.html.

4. Hugh Phillips http://www.instore-research.com/Images/Hugh%20PFB%20Presentation1.pdf, page 5.

5. Hugh Phillips, The Power of Marketing at Retail, (Alexandria, VA:, POPAI, 2008) 31.

6. Ibid., 32.

7. Hugh Phillips, The Power of Marketing at Retail, (Alexandria, VA, POPAI, 2008), pages 34–36.

8. Roger Blackwell, Retail Marketing, Orlando, FL (2003).

9. Ibid.

10. Ibid.

11. Christoph Haibock, NeuroMarketing at Retail, Dubai (2005).