As previously explained, JavaScript doesn't provide support for interfaces or multiple inheritance. JavaScript allows you to add properties and methods on the fly; therefore, we might create a function that takes advantage of this possibility to emulate multiple inheritance and generate an object that combines two existing objects, a technique known as mix-in.

However, instead of creating functions to create a mix-in, we will create constructor functions and use compositions to access objects within objects. We want to create an application by taking advantage of the feature provided by JavaScript.

The following lines show the code for the ComicCharacter constructor function in JavaScript:

function ComicCharacter(nickName) {

this.nickName = nickName;

}The constructor function receives the nickName argument and uses this value to initialize the nickName field.

The following lines show the code for the GameCharacter constructor function in JavaScript:

function GameCharacter(fullName, initialScore, x, y) {

this.fullName = fullName;

this.initialScore = initialScore;

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

}The constructor function receives four arguments: fullName, score, x, and y and uses these values to initialize fields with the same name.

The following lines show the code for the Alien constructor function in JavaScript:

function Alien(numberOfEyes) {

this.numberOfEyes = numberOfEyes;

}The constructor function receives the numberOfEyes argument and uses this value to initialize the numberOfEyes field.

The following lines show the code for the Wizard constructor function in JavaScript:

function Wizard(spellPower) {

this.spellPower = spellPower;

}The constructor function receives the spellPower argument and uses this value to initialize the spellPower field.

The following lines show the code for the Knight constructor function in JavaScript:

function Knight(swordPower, swordHeight) {

this.swordPower = swordPower;

this.swordHeight = swordHeight;

}The constructor function receives two arguments: swordPower and swordHeight. The function uses these values to initialize fields with the same name.

We declared five constructor functions that receive arguments and initialize fields with the same name used for all the arguments. We will use these constructor functions to create instances that we will save within fields of other objects.

Now, we will declare a constructor function that saves the ComicCharacter instance in the comicCharacter field. The following lines show the code for the AngryDog constructor function:

function AngryDog(nickName) { this.comicCharacter = new ComicCharacter(nickName); Object.defineProperty(this, "nickName", { get: function() { return this.comicCharacter.nickName; } }); this.drawSpeechBalloon = function(message, destination) { var composedMessage = ""; if (destination) { composedMessage = destination.nickName + ", " + message; } else { composedMessage = message; } console.log(this.nickName + ' -> "' + composedMessage + '"'), } this.drawThoughtBalloon = function(message) { console.log(this.nickName + ' ***' + message + '***') } }

The AngryDog constructor function receives nickName as its argument. The function uses this argument to call the ComicCharacter constructor function in order to create an instance and save it in the comicCharacter field.

The preceding code defines a nickName read-only property whose getter function returns the value of the nickName field of the previously created ComicCharacter object, which is accessed through this.comicCharacter.nickName. This way, whenever we create the AngryDog object and retrieve the value of its nickname property, the instance will use the saved ComicCharacter object to return the value of its nickName field.

The AngryDog constructor function declares the drawSpeechBalloon method. This method composes a message based on the value of the message and destination parameters and prints a message in a specific format that includes the nickName value as its prefix. If the destination parameter is specified, the preceding code uses the value of the nickName field or property.

In addition, the constructor function declares the code for the drawThoughtBalloon method. This method also prints a message with the nickName value as its prefix. So, the AngryDog constructor function defines two methods that use the ComicCharacter object to access its nickName field through the nickName property.

Now, we will declare another constructor function that saves the ComicCharacter instance in the comicCharacter field. The following lines show the code for the AngryCat constructor function:

function AngryCat(nickName, age) { this.comicCharacter = new ComicCharacter(nickName); this.age = age; Object.defineProperty(this, "nickName", { get: function() { return this.comicCharacter.nickName; } }); this.drawSpeechBalloon = function(message, destination) { var composedMessage = ""; if (destination) { composedMessage = destination.nickName + ' === ' + this.nickName + ' ---> "' + message + '"'; } else { composedMessage = this.nickName + ' -> "'; if (this.age > 5) { composedMessage += "Meow"; } else { composedMessage += "Meeeooow Meeeooow"; } composedMessage += ' ' + message + '"'; } console.log(composedMessage); } this.drawThoughtBalloon = function(message) { console.log(this.comicCharacter.nickName + ' ***' + message + '***'), } }

The AngryCat constructor function receives two arguments: nickName and age. This function uses the nickname argument to call the ComicCharacter constructor function in order to create an instance and save it in the comicCharacter field. The code initializes the age field with the value received in the age argument.

As happened in the AngryCat constructor function, the preceding code also defines the nickName read-only property whose getter function returns the value of the nickName field of the previously created ComicCharacter object, which is accessed through this.comicCharacter.nickName. This way, whenever we create an AngryCat object and retrieve the value of its nickname property, the instance will use the saved ComicCharacter object to return the value of its nickName field.

The AngryDog constructor function declares the drawSpeechBalloon method that composes a message based on the value of the age attribute and the values of the message and destination parameters. The drawSpeechBalloon method prints a message in a specific format that includes the nickName value as its prefix. If the destination parameter is specified, the code uses the value of the nickName field or property.

In addition, the constructor function declares the code for the drawThoughtBalloon method. This method also prints a message including the nickName value as its prefix. So, as happened with

AngryDog, the AngryCat constructor function defines two methods that use the ComicCharacter object to access its nickName field through the nickName property.

We want the previously coded AngryCat constructor function to be able to work as both the comic and game character. In order to do so, we will add some arguments to the constructor function and save the GameCharacter instance in the gameCharacter field (among other changes). Here is the code for the new AngryCat constructor function:

function AngryCat(nickName, age, fullName, initialScore, x, y) {

this.comicCharacter = new ComicCharacter(nickName);

this.gameCharacter = new GameCharacter(fullName, initialScore, x, y);

this.age = age;We added the necessary arguments: fullName, initialScore, x, and y to create the GameCharacter object. This way, we have access to the GameCharacter object through this.gameCharacter. The following code adds the same read-only nickName property that we defined in the previous version of the constructor function and four additional properties:

Object.defineProperty(this, "nickName", {

get: function() {

return this.comicCharacter.nickName;

}

});

Object.defineProperty(this, "fullName", {

get: function() {

return this.gameCharacter.fullName;

}

});

Object.defineProperty(this, "score", {

get: function() {

return this.gameCharacter.score;

},

set: function(val) {

this.gameCharacter.score = val;

}

});

Object.defineProperty(this, "x", {

get: function() {

return this.gameCharacter.x;

},

set: function(val) {

this.gameCharacter.x = val;

}

});

Object.defineProperty(this, "y", {

get: function() {

return this.gameCharacter.y;

},

set: function(val) {

this.gameCharacter.y = val;

}

});The preceding code defines the fullName read-only property whose getter function returns the value of the fullName field of the previously created GameCharacter object, which is accessed through this.gameCharacter.fullName. This way, whenever we create the AngryCat object and retrieve the value of its fullName property, the instance will use the saved GameCharacter object to return the value of its fullName field. The other three new properties (score, x, and y) use the same technique with the difference that they also define setter methods that assign a new value to the field with the same name defined in the GameCharacter object.

In this case, the GameCharacter object uses fields and doesn't define properties with a specific code—such as validations—in the setter method. However, imagine a more complex scenario in which the GameCharacter object requires many validations and defines properties instead of fields. We would be reusing these validations by delegating the getter and setter methods to the GameCharacter object just by reading and writing to its properties.

The following code defines the methods that we defined in the previous version of the constructor function:

this.drawSpeechBalloon = function(message, destination) {

var composedMessage = "";

if (destination) {

composedMessage = destination.nickName + ' === ' +

this.nickName + ' ---> "' + message + '"';

} else {

composedMessage = this.nickName + ' -> "';

if (this.age > 5) {

composedMessage += "Meow";

} else {

composedMessage += "Meeeooow Meeeooow";

}

composedMessage += ' ' + message + '"';

}

console.log(composedMessage);

}

this.drawThoughtBalloon = function(message) {

console.log(this.nickName + ' ***' + message + '***'),

}The following code declares three methods: draw, move, and isIntersectingWith. These methods access the previously defined properties of fullName, x, and y:

this.draw = function(x, y) {

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

console.log("Drawing AngryCat " + this.fullName +

" at x: " + this.x +

", y: " + this.y);

}

this.move = function(x, y) {

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

console.log("Drawing AngryCat " + this.fullName +

" at x: " + this.x +

", y: " + this.y);

}

this.isIntersectingWith = function(otherCharacter) {

return ((this.x == otherCharacter.x) &&

(this.y == otherCharacter.y));

}Tip

JavaScript allows you to add attributes, properties, and methods to any object at any time. We take advantage of this feature to extend the object created with the AngryCat constructor function to AngryCat + Alien, AngryCat + Wizard, and AngryCat + Knight. We will create and save an instance of the Alien, Wizard, or Knight objects and add the necessary methods and properties to extend our AngryCat object on the fly.

The following code declares the createAlien method that receives the numberOfEyes argument. The method calls the Alien constructor function with the numberOfEyes value received in the argument and saves the Alien instance in the alien field. The next few lines add the numberOfEyes property. This works as a bridge to the this.alien.numberOfEyes attribute. The following code also adds two methods: appear and disappear:

this.createAlien = function(numberOfEyes) {

this.alien = new Alien(numberOfEyes);

Object.defineProperty(this, "numberOfEyes", {

get: function() {

return this.alien.numberOfEyes;

},

set: function(val) {

this.alien.numberOfEyes = val;

}

});

this.appear = function() {

console.log("I'm " + this.fullName +

" and you can see my " + this.numberOfEyes +

" eyes.");

}

this.disappear = function() {

console.log(this.fullName + " disappears.");

}

}The following code declares the createWizard method that receives the spellPower argument. The method calls the Wizard constructor function with the spellPower value received in the argument and saves the Wizard instance in the wizard field. The next few lines add the spellPower property. This works as a bridge to the this.wizard.spellPower attribute. The following code also adds the disappearAlien method that receives the alien argument and uses its numberOfEyes field:

this.createWizard = function(spellPower) {

this.wizard = new Wizard(spellPower);

Object.defineProperty(this, "spellPower", {

get: function() {

return this.wizard.spellPower;

},

set: function(val) {

this.wizard.spellPower = val;

}

});

this.disappearAlien = function(alien) {

console.log(this.fullName + " uses his " +

this.spellPower + " to make the alien with " +

alien.numberOfEyes + " eyes disappear.");

}

}Finally, the following code declares the createKnight method. This method receives two arguments: swordPower and swordHeight and calls the Knight constructor function with the swordPower and swordHeight values received in all the arguments and saves the Knight instance in the knight field. The next few lines add the swordPower and swordHeight properties that work as a bridge to the this.wizard.swordPower and this.wizard.swordHeight attributes. The following code also adds the unsheathSword method. This method receives the target argument and uses its numberOfEyes field and calls another new method: writeLinesAboutTheSword. Note that with the following lines, we finish the code for the AngryCat constructor function:

this.createKnight = function(swordPower, swordHeight) {

this.knight = new Knight(swordPower, swordHeight);

Object.defineProperty(this, "swordPower", {

get: function() {

return this.knight.swordPower;

},

set: function(val) {

this.knight.swordPower = val;

}

});

Object.defineProperty(this, "swordHeight", {

get: function() {

return this.knight.swordHeight;

},

set: function(val) {

this.knight.swordHeight = val;

}

});

this.writeLinesAboutTheSword = function() {

console.log(this.fullName + " unsheaths his sword.");

console.log("Sword Power: " + this.swordPower +

". Sword Weight: " + this.swordWeight);

};

this.unsheathSword = function(target) {

this.writeLinesAboutTheSword();

if (target) {

console.log("The sword targets an alien with " +

target.numberOfEyes + " eyes.");

}

}

}

}Now, we will code three new constructor functions: AngryCatAlien, AngryCatWizard, and AngryCatKnight. These constructor functions allows you to easily create instances of AngryCat + Alien, AngryCat + Wizard, and AngryCat + Knight.

The following lines show the code for the AngryCatAlien constructor function, which receives all the necessary arguments to call the AngryCat constructor function. Then, it calls the createAlien method for the created object. Finally, the following code returns the object after the call to createAlien that added properties and methods:

var AngryCatAlien = function(nickName, age, fullName, initialScore, x, y, numberOfEyes) {

var alien = new AngryCat(nickName, age, fullName, initialScore, x, y);

alien.createAlien(numberOfEyes);

return alien;

}The following lines show the code for the AngryCatWizard constructor function, which receives all the necessary arguments to call the AngryCat constructor function. Then, it calls the createWizard method for the created object. Finally, the following code returns the object after the call to createWizard that added properties and methods:

var AngryCatWizard = function(nickName, age, fullName, initialScore, x, y, spellPower) {

var wizard = new AngryCat(nickName, age, fullName, initialScore, x, y);

wizard.createWizard(spellPower);

return wizard;

}The following lines show the code for the AngryCatKnight constructor function. This function receives all the necessary arguments to call the AngryCat constructor function. Then, it calls the createKnight method for the created object. Finally, the following code returns the object after the call to createKnight that added properties and methods:

var AngryCatKnight = function(nickName, age, fullName, initialScore, x, y, swordPower, swordHeight) {

var knight = new AngryCat(nickName, age, fullName, initialScore, x, y);

knight.createKnight(swordPower, swordHeight);

return knight;

}The following table summarizes the objects that are included in other objects after we create instances with all the different constructor functions:

|

Constructor function |

Includes instances of |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

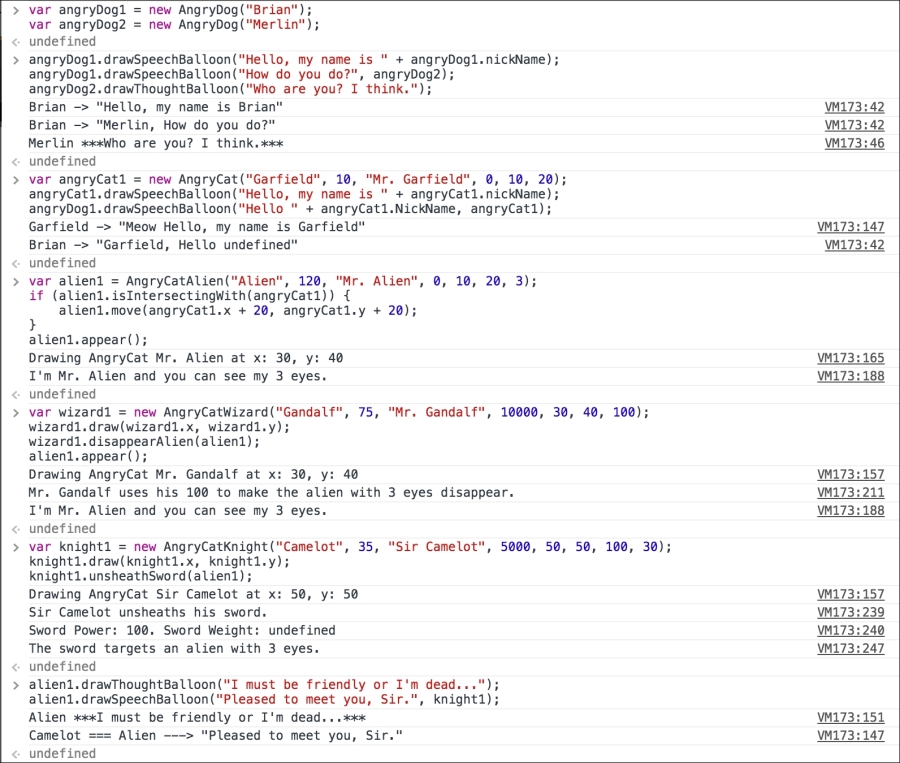

Now, we will work with instances created using all the previously declared constructor functions. In the following code, the first two lines create two AngryDog objects named angryDog1 and angryDog2. Then, the code calls the drawSpeechBalloon method for angryDog1 twice with a different number of arguments. The second call to this method passes angryDog2 as the second argument because angryDog2 is an AngryDog object and includes the nickName property:

var angryDog1 = new AngryDog("Brian");

var angryDog2 = new AngryDog("Merlin");

angryDog1.drawSpeechBalloon("Hello, my name is " + angryDog1.nickName);

angryDog1.drawSpeechBalloon("How do you do?", angryDog2);

angryDog2.drawThoughtBalloon("Who are you? I think.");The following code creates the AngryCat object named angryCat1. Its nickName is Garfield. The next line calls the drawSpeechBalloon method for the new instance to introduce Garfield in the comic character. Then, angryDog1 calls the drawSpeechBalloon method and passes angryCat1 as the destination argument because angryCat1 is the AngryCat object and includes the nickName property. Thus, we can also use AngryCat objects whenever we need the argument that provides the nickName property or field:

var angryCat1 = new AngryCat("Garfield", 10, "Mr. Garfield", 0, 10, 20);

angryCat1.drawSpeechBalloon("Hello, my name is " + angryCat1.nickName);

angryDog1.drawSpeechBalloon("Hello " + angryCat1.NickName, angryCat1);

The following code creates the AngryCatAlien object named alien1. Its nickName is Alien. The next few lines check whether the call to the isIntersectingWith method with angryCat1 as its parameter returns true. The method requires an instance that provides the x and y fields or properties as the argument. We can use angryCat1 as the argument because one of its included objects is ComicCharacter; therefore, it provides the x and y attributes. This method will return true because the x and y properties of both instances have the same value. The line within the if block calls the move method for alien1. Then, the following code also calls the appear method:

var alien1 = AngryCatAlien("Alien", 120, "Mr. Alien", 0, 10, 20, 3);

if (alien1.isIntersectingWith(angryCat1)) {

alien1.move(angryCat1.x + 20, angryCat1.y + 20);

}

alien1.appear();The first line in the following code creates the AngryCatWizard object named wizard1. Its nickName is Gandalf. The next lines call the draw method and then the disappearAlien method with alien1 as the parameter. The method requires an instance that provides the numberOfEyes field or property as the argument. We can use alien1 as the argument because one of its included objects is Alien; therefore, it includes the numberOfEyes field or property. Then, a call to the appear method for alien1 makes the alien with three eyes appear again:

var wizard1 = new AngryCatWizard("Gandalf", 75, "Mr. Gandalf", 10000, 30, 40, 100);

wizard1.draw(wizard1.x, wizard1.y);

wizard1.disappearAlien(alien1);

alien1.appear();The first line in the following code creates the AngryCatKnight object named knight1. Its nickName is Camelot. The next lines call the draw method and then the unsheathSword method with alien1 as the parameter. The method requires an instance that provides the

numberOfEyes field or property as the argument. We can use alien1 as the argument because one of its included objects is Alien; therefore, it includes the numberOfEyes attribute:

var knight1 = new AngryCatKnight("Camelot", 35, "Sir Camelot", 5000, 50, 50, 100, 30);

knight1.draw(knight1.x, knight1.y);

knight1.unsheathSword(alien1);Finally, the following code calls the drawThoughtBalloon and drawSpeechBalloon methods for alien1. We can do this because alien1 is the AngryCatAlien object and includes the methods defined in the AngryCat constructor function. The call to the drawSpeechBalloon method passes knight1 as the destination argument because knight1 is the AngryCatKnight object. Thus, we can also use instances of AngryCatKnight whenever we need an argument that provides the nickName property or field:

alien1.drawThoughtBalloon("I must be friendly or I'm dead...");

alien1.drawSpeechBalloon("Pleased to meet you, Sir.", knight1);After you execute all the preceding code snippets, you will see the following output on the JavaScript console (see Figure 2):

Brian -> "Hello, my name is Brian" Brian -> "Merlin, How do you do?" Merlin ***Who are you? I think.*** Garfield -> "Meow Hello, my name is Garfield" Brian -> "Garfield, Hello undefined" Drawing AngryCat Mr. Alien at x: 30, y: 40 I'm Mr. Alien and you can see my 3 eyes. Drawing AngryCat Mr. Gandalf at x: 30, y: 40 Mr. Gandalf uses his 100 to make the alien with 3 eyes disappear. I'm Mr. Alien and you can see my 3 eyes. Drawing AngryCat Sir Camelot at x: 50, y: 50 Sir Camelot unsheaths his sword. Sword Power: 100. Sword Weight: undefined The sword targets an alien with 3 eyes. Alien ***I must be friendly or I'm dead...*** Camelot === Alien ---> "Pleased to meet you, Sir."

Figure 2