Chapter 12. if Tests

This chapter presents the Python if statement, which is the main statement used for selecting from alternative actions based on test results. Because this is our first in-depth look at compound statements—statements that embed other statements—we will also explore the general concepts behind the Python statement syntax model here in more detail than we did in the introduction in Chapter 10. And, because the if statement introduces the notion of tests, this chapter will also deal with Boolean expressions, and fill in some details on truth tests in general.

if Statements

In simple terms, the Python if statement selects actions to perform. It’s the primary selection tool in Python, and represents much of the logic a Python program possesses. It’s also our first compound statement. Like all compound Python statements, the if statement may contain other statements, including other ifs. In fact, Python lets you combine statements in a program sequentially (so that they execute one after another), and in an arbitrarily nested fashion (so that they execute only under certain conditions).

General Format

The Python if statement is typical of if statements in most procedural languages. It takes the form of an if test, followed by one or more optional elif (“else if”) tests, and a final optional else block. The tests and the else part each have an associated block of nested statements, indented under a header line. When the if statement runs, Python executes the block of code associated with the first test that evaluates to true, or the else block if all tests prove false. The general form of an if statement looks like this:

if <test1>: # if test <statements1> # Associated block elif <test2>: # Optional elifs <statements2> else: # Optional else <statements3>

Basic Examples

To demonstrate, let’s look at a few simple examples of the if statement at work. All parts are optional, except the initial if test and its associated statements; in the simplest case, the other parts are omitted:

>>>

if 1:...print 'true'... true

Notice how the prompt changes to ... for continuation lines in the basic interface used here (in IDLE, you’ll simply drop down to an indented line instead—hit Backspace to back up); a blank line terminates and runs the entire statement. Remember that 1 is Boolean true, so this statement’s test always succeeds. To handle a false result, code the else:

>>>

if not 1:...print 'true'...else:...print 'false'... false

Multiway Branching

Now, here’s an example of a more complex if statement, with all its optional parts present:

>>>

x = 'killer rabbit'>>>if x == 'roger':...print "how's jessica?"...elif x == 'bugs':...print "what's up doc?"...else:...print 'Run away! Run away!'... Run away! Run away!

This multiline statement extends from the if line through the else block. When it’s run, Python executes the statements nested under the first test that is true, or the else part if all tests are false (in this example, they are). In practice, both the elif and else parts may be omitted, and there may be more than one statement nested in each section. Note that the words if, elif, and else are associated by the fact that they line up vertically, with the same indentation.

If you’ve used languages like C or Pascal, you might be interested to know that there is no switch or case statement in Python that selects an action based on a variable’s value. Instead, multiway branching is coded either as a series of if/elif tests, as in the prior example, or by indexing dictionaries or searching lists. Because dictionaries and lists can be built at runtime, they’re sometimes more flexible than hardcoded if logic:

>>>

choice = 'ham'>>>print {'spam': 1.25,# A dictionary-based 'switch' ...'ham': 1.99,# Use has_key or get for default ...'eggs': 0.99,...'bacon': 1.10}[choice]1.99

Although it may take a few moments for this to sink in the first time you see it, this dictionary is a multiway branch—indexing on the key choice branches to one of a set of values, much like a switch in C. An almost equivalent but more verbose Python if statement might look like this:

>>>

if choice == 'spam':...print 1.25...elif choice == 'ham':...print 1.99...elif choice == 'eggs':...print 0.99...elif choice == 'bacon':...print 1.10...else:...print 'Bad choice'... 1.99

Notice the else clause on the if here to handle the default case when no key matches. As we saw in Chapter 8, dictionary defaults can be coded with has_key tests, get method calls, or exception catching. All of the same techniques can be used here to code a default action in a dictionary-based multiway branch. Here’s the get scheme at work with defaults:

>>>

branch = {'spam': 1.25,...'ham': 1.99,...'eggs': 0.99}>>>print branch.get('spam', 'Bad choice')1.25 >>>print branch.get('bacon', 'Bad choice')Bad choice

Dictionaries are good for associating values with keys, but what about the more complicated actions you can code in if statements? In Part IV, you’ll learn that dictionaries can also contain functions to represent more complex branch actions and implement general jump tables. Such functions appear as dictionary values, are often coded as lambdas, and are called by adding parentheses to trigger their actions; stay tuned for more on this topic.

Although dictionary-based multiway branching is useful in programs that deal with more dynamic data, most programmers will probably find that coding an if statement is the most straightforward way to perform multiway branching. As a rule of thumb in coding, when in doubt, err on the side of simplicity and readability.

Python Syntax Rules

I introduced Python’s syntax model in Chapter 10. Now that we’re stepping up to larger statements like the if, this section reviews and expands on the syntax ideas introduced earlier. In general, Python has a simple, statement-based syntax. But, there are a few properties you need to know about:

Statements execute one after another, until you say otherwise. Python normally runs statements in a file or nested block in order from first to last, but statements like

if(and, as you’ll see, loops) cause the interpreter to jump around in your code. Because Python’s path through a program is called the control flow, statements such asifthat affect it are often called control-flow statements.Block and statement boundaries are detected automatically. As we’ve seen, there are no braces or “begin/end” delimiters around blocks of code in Python; instead, Python uses the indentation of statements under a header to group the statements in a nested block. Similarly, Python statements are not normally terminated with semicolons; rather, the end of a line usually marks the end of the statement coded on that line.

Compound statements = header, “:,” indented statements. All compound statements in Python follow the same pattern: a header line terminated with a colon, followed by one or more nested statements, usually indented under the header. The indented statements are called a block (or sometimes, a suite). In the

ifstatement, theelifandelseclauses are part of theif, but are also header lines with nested blocks of their own.Blank lines, spaces, and comments are usually ignored. Blank lines are ignored in files (but not at the interactive prompt). Spaces inside statements and expressions are almost always ignored (except in string literals, and when used for indentation). Comments are always ignored: they start with a

#character (not inside a string literal), and extend to the end of the current line.Docstrings are ignored, but saved and displayed by tools. Python supports an additional comment form called documentation strings (docstrings for short), which, unlike

#comments, are retained at runtime for inspection. Docstrings are simply strings that show up at the top of program files and some statements. Python ignores their contents, but they are automatically attached to objects at runtime, and may be displayed with documentation tools. Docstrings are part of Python’s larger documentation strategy, and are covered in the last chapter in this part of the book.

As you’ve seen, there are no variable type declarations in Python; this fact alone makes for a much simpler language syntax than what you may be used to. But, for most new users, the lack of the braces and semicolons used to mark blocks and statements in many other languages seems to be the most novel syntactic feature of Python, so let’s explore what this means in more detail.

Block Delimiters

Python detects block boundaries automatically, by line indentation—that is, the empty space to the left of your code. All statements indented the same distance to the right belong to the same block of code. In other words, the statements within a block line up vertically, as in a column. The block ends when the end of the file or a lesser-indented line is encountered, and more deeply nested blocks are simply indented further to the right than the statements in the enclosing block.

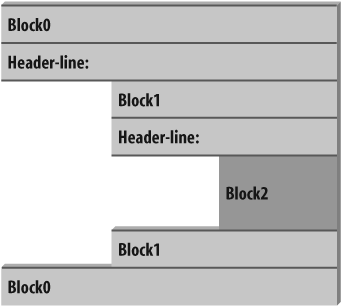

For instance, Figure 12-1 demonstrates the block structure of the following code:

x = 1 if x: y = 2 if y: print 'block2' print 'block1' print 'block0'

This code contains three blocks: the first (the top-level code of the file) is not indented at all, the second (within the outer if statement) is indented four spaces, and the third (the print statement under the nested if) is indented eight spaces.

In general, top-level (unnested) code must start in column 1. Nested blocks can start in any column; indentation may consist of any number of spaces and tabs, as long as it’s the same for all the statements in a given single block. That is, Python doesn’t care how you indent your code; it only cares that it’s done consistently. Technically, tabs count for enough spaces to move the current column number up to a multiple of 8, but it’s usually not a good idea to mix tabs and spaces within a block—use one or the other.

The only major place in Python where whitespace matters is when it’s used to the left of your code, for indentation; in most other contexts, space can be coded or not. However, indentation is really part of Python syntax, not just a stylistic suggestion: all the statements within any given single block must be indented to the same level, or Python reports a syntax error. This is intentional—because you don’t need to explicitly mark the start and end of a nested block of code, some of the syntactic clutter found in other languages is unnecessary in Python.

Making indentation part of the syntax model also enforces consistency, a crucial component of readability in structured programming languages like Python. Python’s syntax is sometimes described as “what you see is what you get”—the indentation of each line of code unambiguously tells readers what it is associated with. This consistent appearance makes Python code easier to maintain and reuse.

Consistently indented code always satisfies Python’s rules. Moreover, most text editors (including IDLE) make it easy to follow Python’s indentation model by automatically indenting code as you type it.

Statement Delimiters

A statement in Python normally ends at the end of the line on which it appears. When a statement is too long to fit on a single line, though, a few special rules may be used to make it span multiple lines:

Statements may span multiple lines if you’re continuing an open syntactic pair. Python lets you continue typing a statement on the next line if you’re coding something enclosed in a

( ),{}, or[]pair. For instance, expressions in parentheses, and dictionary and list literals, can span any number of lines; your statement doesn’t end until the Python interpreter reaches the line on which you type the closing part of the pair (a),}, or]). Continuation lines can start at any indentation level, and should all be vertically aligned.Statements may span multiple lines if they end in a backslash. This is a somewhat outdated feature, but if a statement needs to span multiple lines, you can also add a backslash (

) at the end of the prior line to indicate you’re continuing on the next line. Because you can also continue by adding parentheses around long constructs, backslashes are almost never used.Triple-quoted string literals can span multiple lines. Very long string literals can span lines arbitrarily; in fact, the triple-quoted string blocks we met in Chapter 7 are designed to do so.

Other rules. There are a few other points to mention with regard to statement delimiters. Although uncommon, you can terminate statements with a semicolon—this convention is sometimes used to squeeze more than one simple (noncompound) statement onto a single line. Also, comments and blank lines can appear anywhere in a file; comments (which begin with a

#character) terminate at the end of the line on which they appear.

A Few Special Cases

Here’s what a continuation line looks like using the open pairs rule. You can span delimited constructs across any number of lines:

L = ["Good", "Bad", "Ugly"] # Open pairs may span lines

This works for anything in parentheses, too: expressions, function arguments, function headers (see Chapter 15), and so on. If you like using backslashes to continue lines, you can, but it’s not common practice in Python:

if a == b and c == d and d == e and f == g: print 'olde' # Backslashes allow continuations...

Because any expression can be enclosed in parentheses, you can usually use this technique instead if you need your code to span multiple lines:

if (a == b and c == d and d == e and e == f): print 'new' # But parentheses usually do too

As another special case, Python allows you to write more than one noncompound statement (i.e., statements without nested statements) on the same line, separated by semicolons. Some coders use this form to save program file real estate, but it usually makes for more readable code if you stick to one statement per line for most of your work:

x = 1; y = 2; print x # More than one simple statement

And, finally, Python lets you move a compound statement’s body up to the header line, provided the body is just a simple (noncompound) statement. You’ll most often see this used for simple if statements with a single test and action:

if 1: print 'hello' # Simple statement on header line

You can combine some of these special cases to write code that is difficult to read, but I don’t recommend it; as a rule of thumb, try to keep each statement on a line of its own, and indent all but the simplest of blocks. Six months down the road, you’ll be happy you did.

Truth Tests

The notions of comparison, equality, and truth values were introduced in Chapter 9. Because the if statement is the first statement we’ve looked at that actually uses test results, we’ll expand on some of these ideas here. In particular, Python’s Boolean operators are a bit different from their counterparts in languages like C. In Python:

Any nonzero number or nonempty object is true.

Zero numbers, empty objects, and the special object

Noneare considered false.Comparisons and equality tests are applied recursively to data structures.

Comparisons and equality tests return

TrueorFalse(custom versions of 1 and 0).Boolean

andandoroperators return a true or false operand object.

In short, Boolean operators are used to combine the results of other tests. There are three Boolean expression operators in Python:

-

X and Y Is true if both

XandYare true.-

X or Y Is true if either

XorYis true.-

not X Is true if

Xis false (the expression returnsTrueorFalse).

Here, X and Y may be any truth value, or an expression that returns a truth value (e.g., an equality test, range comparison, and so on). Boolean operators are typed out as words in Python (instead of C’s &&, ||, and !). Also, Boolean and and or operators return a true or false object in Python, not the values True or False. Let’s look at a few examples to see how this works:

>>>

2 < 3, 3 < 2# Less-than: return 1 or 0 (True, False)

Magnitude comparisons such as these return True or False as their truth results, which, as we learned in Chapter 5 and Chapter 9, are really just custom versions of the integers 1 and 0 (they print themselves differently, but are otherwise the same).

On the other hand, the and and or operators always return an object instead—either the object on the left side of the operator, or the object on the right. If we test their results in if or other statements, they will be as expected (remember, every object is inherently true or false), but we won’t get back a simple True or False.

For or tests, Python evaluates the operand objects from left to right, and returns the first one that is true. Moreover, Python stops at the first true operand it finds. This is usually called short-circuit evaluation, as determining a result short-circuits (terminates) the rest of the expression:

>>>

2 or 3, 3 or 2# Return left operand if true (2, 3) # Else, return right operand (true or false) >>>[ ] or 33 >>>[ ] or { }{ }

In the first line of the preceding example, both operands (2 and 3) are true (i.e., are nonzero), so Python always stops and returns the one on the left. In the other two tests, the left operand is false (an empty object), so Python simply evaluates and returns the object on the right (which may happen to have either a true or false value when tested).

and operations also stop as soon as the result is known; however, in this case, Python evaluates the operands from left to right, and stops at the first false object:

>>>

2 and 3, 3 and 2# Return left operand if false (3, 2) # Else, return right operand (true or false) >>>[ ] and { }[ ] >>>3 and [ ][ ]

Here, both operands are true in the first line, so Python evaluates both sides, and returns the object on the right. In the second test, the left operand is false ([]), so Python stops and returns it as the test result. In the last test, the left side is true (3), so Python evaluates and returns the object on the right (which happens to be a false []).

The end result of all this is the same as in C and most other languages—you get a value that is logically true or false, if tested in an if or while. However, in Python, Booleans return either the left or right object, not a simple integer flag.

This behavior of and and or may seem esoteric at first glance, but see this chapter’s sidebar "Why You Will Care: Booleans" for examples of how it is sometimes used to advantage in coding by Python programmers.

The if/else Ternary Expression

One common role for Boolean operators in Python is to code an expression that runs the same as an if statement. Consider the following statement, which sets A to either Y or Z, based on the truth value of X:

if X: A = Y else: A = Z

Sometimes, as in this example, the items involved in such a statement are so simple that it seems like overkill to spread them across four lines. At other times, we may want to nest such a construct in a larger statement instead of assigning its result to a variable. For these reasons (and, frankly, because the C language has a similar tool[31]), Python 2.5 introduced a new expression format that allows us to say the same thing in one expression:

A = Y if X else Z

This expression has the exact same effect as the preceding four-line if statement, but it’s simpler to code. As in the statement equivalent, Python runs expression Y only if X turns out to be true, and runs expression Z only if X turns out to be false. That is, it short-circuits, as Boolean operators in general do. Here are some examples of it in action:

>>>

A = 't' if 'spam' else 'f'# Nonempty is true >>>A't' >>>A = 't' if '' else 'f'>>>A'f'

Prior to Python 2.5 (and after 2.5, if you insist), the same effect can be achieved by a careful combination of the and and or operators because they return either the object on the left side or the object on the right:

A = ((X and Y) or Z)

This works, but there is a catch—you have to be able to assume that Y will be Boolean true. If that is the case, the effect is the same: the and runs first, and returns Y if X is true; if it’s not, the or simply returns Z. In other words, we get “if X then Y else Z.”

This and/or combination also seems to require a “moment of great clarity” to understand the first time you see it, and it’s no longer required as of 2.5—use the more mnemonic Y if X else Z instead if you need this as an expression, or use a full if statement if the parts are nontrivial.

As a side note, using the following expression in Python is similar because the bool function will translate X into the equivalent of integer 1 or 0, which can then be used to pick true and false values from a list:

A = [Z, Y][bool(X)]

For example:

>>>

['f', 't'][bool('')]'f' >>>['f', 't'][bool('spam')]'t'

However, this isn’t exactly the same, because Python will not short-circuit—it will always run both Z and Y, regardless of the value of X. Because of such complexities, you’re better off using the simpler and more easily understood if/else expression as of Python 2.5. Again, though, you should use even that sparingly, and only if its parts are all fairly simple; otherwise, you’re better off coding the full if statement form to make changes easier in the future. Your coworkers will be happy you did.

Still, you may see the and/or version in code written prior to 2.5 (and in code written by C programmers who haven’t quite let go of their coding pasts).

Chapter Summary

In this chapter, we studied the Python if statement. Because this was our first compound and logical statement, we also reviewed Python’s general syntax rules, and explored the operation of truth tests in more depth than we were able to previously. Along the way, we also looked at how to code multiway branching in Python, and learned about the if/else expression introduced in Python 2.5.

The next chapter continues our look at procedural statements by expanding on the while and for loops. There, we’ll learn about alternative ways to code loops in Python, some of which may be better than others. Before that, though, here is the usual chapter quiz.

BRAIN BUILDER

[31] * In fact, Python’s X if Y else Z has a slightly different order than C’s Y ? X : Z. This was reportedly done in response to analysis of common use patterns in Python code, but also partially to discourage ex-C programmers from overusing it! Remember, simple is better than complex, in Python, and elsewhere.