CHAPTER FOUR

THE TOOLS OF ONLINE TEACHING

Technology has changed dramatically since we wrote the first edition of this book and continues to do so at a rapid pace. The course management systems that were newly developing in 2001 have become the foundation on which most online courses are built now. However, that too is changing. Mobile technology is creating a stronghold in education and is being used in both face-to-face and online courses. Tablets such as the iPad and others are beginning to replace notebook and desktop computers. Many colleges and universities have invested in iPads, distributing them to new students and conducting iPad projects, a topic we discuss later in this chapter. Open source course management systems, which have been developed and are supported by communities of users, are quickly replacing the commercial course management systems that have ruled the online education world over the past decade.

Regardless, technology is not the focus of the online course and remains merely the vehicle for course delivery. The late Don Foshee, first president of the Texas Distance Learning Association, remarked in 1999 that the use of technology is only as good as the people and content behind it. He offered some lessons learned from the evolution of technology in education at that time, noting, “Good teaching is good teaching and bad teaching is even worse in a technology-based environment” (p. 26). And he stated what we cannot emphasize enough: nothing substitutes for good planning. Planning should cover the technology to be used, as well as programs to be developed and courses to be taught. These thoughts were true in 1999 and remain true today: technology is the vehicle, not the driver, of the online course.

In this chapter, we look at how technology is being used in education now, noting with caution that with the rapid development of both hardware and software applications, what we say today may not be true even by the time this book is published. We will, however, discuss how to work within the strengths and limitations of the technology available to us, thus assisting instructors in the planning process for their online courses and providing some suggestions for evaluating their technology needs. In addition, we explore ways in which online courses and programs can be developed and delivered when the institution has limited financial resources, which is so much easier today due to the availability of applications on the Internet and the use of mobile technology. We pay special attention to mobile technology: how it is affecting our work and how it can be effectively used for online teaching.

Technology in the Twenty-First Century

In 1999 the National Center for Educational Statistics (NCES) published its first report (no longer available) that discussed the ways in which distance learning technology had advanced and changed. The report's authors noted that the key features of the technology in use were the increased level of interactivity between students and faculty, with the resulting ability to exchange greater amounts of information, greater variety in the types of information that could be exchanged, and significantly shorter amounts of time required for information exchange to occur. The types of online technology to which they were referring included e-mail, chat sessions, electronic bulletin boards, video, CD-ROM, audioconferencing, and desktop videoconferencing. The report cautioned that the use of advanced technologies did not necessarily mean better implementation of distance learning programs. Technology needs vary with instructional and learner needs. In other words, just because various technologies are available does not mean that they need to be used in the delivery of a course. One course may be delivered using only discussion boards, whereas another might make good use of chat or a whiteboard. There have been several updates to the NCES reports since 1999, many of which have focused on learning effectiveness through the use of technology and the degree to which technology is being integrated into teaching.

A survey conducted by Allen and Seaman (2007) revealed that more than two-thirds of forty-three hundred higher education institutions in the United States are offering some form of online education. In addition, 69 percent of traditional and nontraditional universities believe that student demand for online courses will continue to grow. As of 2007, 83 percent of the institutions already offering online courses expected their enrollments in these courses to continue to increase. The primary reasons cited for offering online courses and degrees is to improve student access and increase student completion rates (Allen & Seaman, 2007). Given constituent pressures on institutions in both of these areas, it is clear that online instruction will continue to expand.

A similar trend is happening in the K–12 sector. There are now online programs at the high school level in every state, and online programs are also being offered in every province in Canada. These programs especially serve students living in rural areas or provide access to courses no longer being offered by school districts due to budget cuts. Online education in K–12, also called virtual schooling, is growing at about 30 percent annually (North American Council for Online Learning, 2007). The North American Council for Online Learning and the National Education Association (n.d.) have both developed standards for quality teaching online and are advocating for states to create online teaching credentials.

A 2007 survey of K–12 teachers, administrators, and professional development trainers showed the disparity between the amount of preparation teachers receive to teach online and their preparation for other teaching endeavors. The variance in time devoted ranged from 0 hours to 270 hours annually. In addition, 62 percent of teachers reported having no training prior to teaching online (Rice & Dawley, 2007). Credentialing programs in all states require some competency in computer-assisted instruction, but no state has a credential specifically for online teaching.

Based on this level of demand, it is clear that the need for experienced faculty to teach these classes is very large and that institutions need to develop plans for recruiting, hiring, training, developing, and supporting online faculty (Green, Alejandro, & Brown, 2009). Training and development of faculty to teach online should include both discussion of the tools available to them, along with pedagogical strategy for their use.

Clearly the technology tools available to instructors to create and increase interactivity in online courses are varied and continue to be developed. As we noted earlier, the continuum of technology use in courses is no longer from zero to fully offered using technology; technological tools are generally employed in all courses taught today at all levels. Manning and Johnson (2011) note that the use of technology in education is a process by which we use those tools to address an educational problem. The tools, then, serve the function of supporting learning. Where we once made distinctions between the tools contained within course management systems and those we might encounter on the Web or elsewhere, those distinctions have now blurred. Manning and Johnson note that the proliferation of what are known as Web 2.0 tools (social media, wikis, blogs, and the like, all of which we discuss later) and the ability to link those to a course management system or use them to create the course outside of a course management system have moved us from what was a static approach to course development to a place where instructors can collaborate with students to share authorship for courses.

Again, however, we cannot stress enough that the availability of these tools does not dictate their use. Given that the tools are designed to support learning and address educational problems, instructors should design courses with learning outcomes and objectives in mind, building learning activities that allow students to reach those objectives using technology. The tools used should be chosen to match the outcomes and objectives and serve as a vehicle for reaching them.

We now look specifically at some of those tools—Web 2.0 technologies and mobile technologies—and along the way discuss how matching these tools to outcomes might be effectively done.

Matching the Technology to the Course

The selection of distance learning technologies should involve the assessment of course content, learning outcomes, and interaction needs. No one technology is optimum for achieving all learning objectives, and conversely, instructors will rarely have the latitude to integrate all technologies into a course. Olcott (1999) provided what he called the five I's of effective distance teaching: interaction, introspection, innovation, integration, and information. They continue to be good hallmarks of ways in which to choose appropriate technologies to use in online or hybrid courses:

- Interaction refers not only to the communication that should occur between the student and the instructor and the student with other students but also the interaction between the student and the content of the course. Thus, asynchronous and synchronous communications, as well as the presentation of print materials and links to the Internet, form the technology needs of interaction.

- Introspection is the interpretation, revision, and demonstrated understanding of concepts. Discussion boards, graphics, and even audio and video can be effective technologies to encourage introspection.

- Innovation refers to the ability of instructors to experiment with technologies to address various learning styles and learning cycles students will go through during a course. Thus, combinations of audio, video, synchronous, and asynchronous discussion can provide various opportunities for students to learn. As important as using various technologies is implementing various modes of assessment of student work in a course. Reliance on one means of assessment, such as tests and quizzes, may not align well with the outcomes the instructor is hoping students will achieve (Palloff & Pratt, 2009). Instructors may even choose to offer students choices of ways in which they will be assessed, furthering the goal of student empowerment in the learning process.

- Integration reflects the integration of facts, concepts, theories, and practical application of knowledge. Using case studies, simulation exercises, the production of audio, video, or graphic presentations, and role-play can create a setting in which integration can occur. These collaborative activities can easily be accomplished in an asynchronous environment, and Web 2.0 applications and mobile technology can support their development.

- Information refers to the knowledge and understanding that is a prerequisite for students to move to the next level of learning. Instructors have traditionally thought of the transfer of information that occurs in a lecture. However, reliance on lecture in the online environment tends to reduce the dynamic capacity of an online course, while collaboration and interaction can effectively enhance it (Palloff & Pratt, 2004).

This discussion should illustrate that any form or forms of technology can be used to deliver a course. What is more critical to a successful online course is good learner-centered teaching. Consequently, the first consideration when choosing the forms of technology to be used in a course should be the outcomes to be achieved as well as the technology that students commonly use. All else should flow from there. In many cases, learning outcomes can be achieved with the least complex technology. This also allows the course to be accessed by the majority of users with little difficulty.

Access and accessibility continue to be important considerations in the development and delivery of a course, and mobile technology is helping to close the digital divide: students might not have computers at home or in their dorm rooms, but they are likely to own a cell phone. We now turn our attention to the impact and use of mobile technology in teaching and learning and how they are helping to increase access.

What Are Web 2.0 Technologies?

Web 2.0 refers to the second generation of the World Wide Web, offering higher levels of user interaction and collaboration. Much of Web 2.0 emerged from the desire of young people for self-expression through creation of content posted on the Web, easy communication with peers, and ways to stay connected to friends. However, interest in and engagement with Web 2.0 technologies is no longer relegated to younger people or those who are technologically savvy. Adults are now using Web 2.0 technologies in greater numbers, and businesses are making use of these technologies for marketing purposes and to connect and communicate more effectively with consumers.

Web 2.0 tools range from those that allow personal expression to those that support community building. Educational applications of Web 2.0 technologies are increasing rapidly.

Common Forms of Web 2.0 Technologies

Here we examine some of the more common forms of Web 2.0 technology currently being integrated into online courses, with examples of how they are being used.

Blogs

Blogs (Web logs) are online journals maintained by individuals, which are generally commentaries on particular topics. They are being incorporated into online courses in several ways. Instructors are encouraging students to set up blogs both inside and outside courses in order to serve as a journal of their reflections on the course and, in the case of journalism or writing courses, to experience the “blogosphere” that has become an integral part of journalism today.

Some instructors are using blogs as a means to conduct online courses, having students post assignments in the form of blogs, and asking students as well as experts in the field to comment on the blog postings. Instructors are also using blogs as a substitute for lecturing in that they allow instructors to reflect on course material and bring in additional perspectives.

Learner-Generated Context

Also known as collective intelligence, learner-generated context (LGC) is a system that collects the expertise of a group rather than an individual to make decisions and generate knowledge and can include wikis (defined separately), collaboratively generated digital content (such as through YouTube video content and Flickr graphic content), learning spaces, approaches to learning designed collaboratively by learners, and shared databases.

Learner-generated context is a collection of tools, information, and research conducted by others gathered by a group of learners to create a learning space that meets their needs. The interdisciplinary London Research Group is studying this form of technology and has defined it as “a context created by people interacting together with a common, self-defined or negotiated learning goal. The key aspect of learner generated contexts is that they are generated through the enterprise of those who would previously have been consumers in a context created for them” (Lukin et al., 2007, p. 91). LGC can include the development of wikis, Google Docs, YouTube video content, Flickr, and other digital technologies. It is being used as adjunct material to an online course, but we have not yet encountered a full course developed and delivered through LGC, although this is the goal of those studying this form of technology.

The downside to the use of LGC is that the instructor has limited control of the direction in which learners might go. The upside, as Lukin et al. (2007) noted, is that LGC breaks out of the boundaries of traditional pedagogy and significantly boosts collaboration among students.

Wikis

Wikis are systems that allow the creation and publishing of a web page or website. Wikipedia, is the most well known, but many other wiki sites exist. Anyone with access or permission can contribute to or edit a wiki.

The use of wikis is becoming increasingly popular in online courses, and the ability to create them is now built into many course management systems, although those wikis are not as robust as wiki applications found on the Web, which allow the creation of user accounts for the purpose of developing wikis. Students working on wiki assignments collaborate on gathering information and building a web page where that information is displayed. Students can add to or edit content if they have permission to do so.

Small groups in an online course can be working on multiple wikis simultaneously and can share the final products with the other groups, the instructor, or outside experts. Wikis can easily be added to portfolios for assessment and documentation of student work. Because of the ability to edit at will, wikis usually contain an accessible revision history that indicates the author of the edits. Due to this editing function, however, students need to develop “wiki etiquette” so as to keep collaboration primary and avoid possible conflict as content is deleted or edited.

Podcasts

Podcasts are audio or video recordings posted in an online course or on the Web that can be downloaded and played on a computer or an MP3 player.

Podcasting is another form of Web 2.0 technology that has gained significant popularity in online courses due to the ease of creation, download, and use. Podcasts are generally used for the delivery of just-in-time lecture content from the instructor and can be added to a course by file attachment, posting in iTunes or on YouTube in the case of video, or through an RSS feed, which we discuss in the next section. Given the availability of open source software for the creation of podcasts (Audacity) and vodcasts (iMovie, Windows Movie Maker, Jumpcut) and the ease with which the final products can be made available, students can also create podcasts and vodcasts alone or collaboratively to add content to courses or complete assignments.

RSS

RSS (Really Simple Syndication) feeds refer to real-time information, usually in the form of news, blogs, or podcasts, that can be streamed to a website in real time.

Almost all course management systems allow the inclusion of RSS feeds. Instructors can choose to include them from outside sources that are relevant to course content or create feeds from blogs or any other updated content, such as podcasts as they are created. Students can also subscribe to RSS feeds on mobile devices. The feeds can help keep students abreast of new developments as they occur and students connected to the instructor and the class.

Social Networking

Social networking sites such as MySpace and Facebook allow people to connect with a select group of people around personal or professional interests. MySpace is generally considered a place where younger people (mostly in high school) meet, while Facebook appeals more to college students and adults.

As of September 2012, it was estimated that over 937 million people worldwide were subscribed to Facebook (Internet World Stats, 2012) and 34 million young people were subscribed to MySpace (Social Compare, 2012). Users of social networks establish a list of “friends” with whom they communicate, share information about their lives, and in general connect socially and personally. Many academics are researching the impact of social networks, and some instructors are using social networks as a means by which to deliver online courses. Embedded within Facebook, for example, are applications such as wikis and groupware, useful for creating study groups that allow posting notes and sharing documents. Asynchronous discussion and the posting of files, photos, and other media are all possible with Facebook. Due to privacy concerns on Facebook, however, many instructors are turning to newer applications offered by Google and others, where membership can be restricted.

Twitter is a form of a social networking space that allows short (140 character) microblog entries known as “tweets.” Tweets are delivered instantly to people who have signed up to “follow” a person on Twitter.

Known as a form of social networking, Twitter users, like Facebook and MySpace users, declare the list of people they choose to follow. Unlike Facebook or MySpace, where postings are limited to an identified group of friends, postings to Twitter (known as tweets) can be read by any Twitter user who chooses to follow a particular person. Although replies to Tweets are possible, this does not commonly occur (Angwin, 2009). A study of Twitter (Huberman, Romero, & Wu, 2009) concluded that Twitter users have a very small number of “friends” compared to the number of followers and followees they may have.

Twitter at this juncture is not being widely used in online teaching. However, some instructors are using it to communicate bits of information to students, including websites to visit, experts to follow, and what the instructor is currently reading or recommends for reading (Perez, 2009).

Skype

Skype is an Internet-based phone service that also can be used for conference calling, document sharing, and text messaging. It is becoming a popular online teaching tool for teaching a variety of content areas and particularly in the teaching of languages where voice contact is important.

The ability to use Skype for voice, video, and chat helps instructors and students alike to meet a number of communication needs. When students are located all over the globe, Skype can make both individual and conference calling easy and carries no expense, a significant benefit. Skype also allows file transfers, file sharing, and whiteboarding.

Second Life

Second Life (SL) is a virtual world in which users interact in real time through the use of avatars, which are graphical representations of themselves. It has its own economy and the ability to buy land; many universities own land in SL and are using it to deliver distance learning programs.

Second Life has not achieved the promise in online teaching that was initially predicted. There is a learning curve involved, and several orientation programs to Second Life, along with how to use it in teaching, have emerged to address this challenge. Users create avatars and interact in real time. Because classes are conducted in the virtual world and it is possible for students to speak at any time (versus threaded discussions, which occur in an asynchronous online course), instructors note that a new set of classroom norms needs to be developed to avoid chaos (Nesson, 2007). However, because SL is a virtual world in which instructors and students have physical representation, users believe that it helps to create a sense of community in an online class. The use of avatars has also raised questions about this, given that students can represent themselves as anything from human, to animal, to fantasy creatures. Additional concerns relate to the lack of security in SL: given that this is a virtual world that was not created for academic purposes, students can wander into less-than-desirable areas, creating possible liability issues for academic institutions.

Using Web 2.0 Tools in Online Courses

As with any other form of technology, Web 2.0 technologies have both positives and negatives associated with their use. Some examples of concerns include the following:

- Because these technologies are available in the public domain for the most part, issues of copyright may emerge. Users of Facebook, for example, sign waivers acknowledging that Facebook owns the copyright to materials on the site.

- Another concern relative to the public nature of sites like Facebook and Second Life is that given that they are primarily social in nature, students can “wander” into areas that may be questionable. This raises possible liability issues for universities.

- Because materials are created on and posted to another site, there may be concerns about archiving and loss of content.

- Privacy concerns emerge in the use of social networking sites and Second Life.

- The use of social networking sites also blurs the lines of formality: some instructors object to being “friended” by their students.

- Instructors fear the loss of control that accompanies the collaborative and more social nature of Web 2.0 technologies and are discovering the need to develop new norms for their use.

These concerns must be addressed when using Web 2.0 sources for the creation of community or to extend the reach of an online course. The positive aspects of using these forms of technology, however, may outweigh the negatives. They do have the ability to support the development of an online community, thus contributing to more effective collaboration among students (Palloff & Pratt, 2004). Relying on any one of them to accomplish that task is a bit shortsighted; however, the inclusion of a variety of means by which community is developed in an online course can facilitate this task by increasing the means and amount of communication possible between students as well as between students and instructor. The sense of community can be significantly deepened, thus supporting the ability to collaborate online.

Web 2.0 technologies designed to connect people to one another also serve to increase the sense of social presence in an online course through these various forms of communication. The use of Web 2.0 technologies can help to reduce the isolation and distance that students often feel in an online course and thus are worthy of exploration.

Choosing Technology Wisely

Despite the proliferation of mobile technology and Web 2.0 applications, instructors are required to use the course management system that their academic institution has chosen to deliver online courses or components of their face-to-face courses. However, often they do have the freedom to augment that system with other technologies, such as the mobile technologies or the Web 2.0 technologies we just discussed. How, then, can an instructor make good choices about what to use, given the wide array of what is available?

Manning and Johnson (2011) suggest some broad considerations to aid in these decisions and suggest that these elements be applied to any form of technology being considered for an online course:

- The educational problem the tool is designed to address and solve. Significant analysis should be devoted to this decision lest the tool end up creating rather than solving an educational problem.

- The platform on which the course will be offered. Is this a tool that will supplement a course management system, augment traditional classroom instruction, or be used with a hybrid approach?

- What the tool is best used for. Will it help meet the stated outcomes of the course?

- The cost. Will the cost be borne by the institution or the students themselves? Keep in mind that cost also includes staff time required to support the use of the tool.

- The accessibility of the tool. Aspects of accessibility include the various learning needs of students, technical competence, and the availability of the technology for students. In other words, do students need to acquire or download software in order to use the tool effectively? Is it easily accessed on the Web? Can students with disabilities, who may also be using assistive technologies such as screen readers, easily use it?

Course management systems have been grappling with these issues and working to make their systems accessible. When instructors go outside the course management system, they need to address these same issues themselves:

- What special technical equipment or technical requirements need to be addressed in order to use the tool, and what level of technical expertise, competencies, or skills will be needed to use it? If special equipment is required or students need a high level of competency to use the tool, the instructor must be prepared to offer technical assistance to students or have support staff available to provide the needed help. Manning and Johnson (2011) suggest that knowing the technical competence of students before the course even begins allows the instructor to avoid possible problems through the creation of tutorials or other training to support students in their use of the tool.

- Another evaluation concern for technical tools is whether its use is synchronous versus asynchronous. The use of synchronous tools, where students meet together to use the tool in real time, requires significantly more planning and facilitation than does the use of asynchronous tools, where students can use them at any time and from any place.

- When new technologies are used in a class, they tend to come with new vocabulary. Manning and Johnson (2011) note the need for instructors to learn the vocabulary associated with the tools in use so as to educate students to that vocabulary. Speaking the same language is important when introducing technological tools into an online or hybrid class.

A final and important consideration in choosing technology for online or hybrid courses is ensuring a balance between the tools in use and the outcomes for the course. It's enticing to incorporate all of the new technologies into a course to increase the level of engagement and excitement that they can potentially generate. Too many bells and whistles, however, can overwhelm and confuse students. An important lesson is to choose only the technology that serves learning objectives. Anything beyond that can create more problems than it solves.

When the Technology Is a Problem

If an instructor is put in the position of using technology that was chosen by the institution and is not serving learning objectives well, creativity is the key. Supplementing it with the use of tools available outside the course management system may be appropriate in these cases. It is also important to respond to student concerns about the use of that technology without allowing the concerns to become the focus of the course. Setting up a discussion forum where students can work together on strategies for learning despite the shortcomings of the technology can let students be heard while keeping the focus on learning.

Faculty collaboration is critical to solving these problems at the institutional level. Communicating with one another about the problems experienced and brainstorming ways to solve those problems helps all instructors learn about the technology in use while supporting their students. It is important to convey concerns to administrators as well. It may not be possible to change the technology, but it may be possible to discuss the concerns with the software developer so that future releases can include modifications that are responsive to stakeholder needs.

Evaluating Technology

Including faculty in the selection process of technology for the institution is critical. If at all possible, it is helpful to include students in the process as well. Although these appear to be obvious conclusions, often faculty and students, the prime users of the technology selected, are overlooked in the evaluation and selection process. Often technology-based decisions are made by technical personnel who base their decision on personal use, attendance at vendor-sponsored workshops, reading about it in trade publications, or having used other products from the same vendor or at other institutions. Clearly the ability of technical personnel to support the chosen technology should be one of the criteria used to evaluate what the institution adopts. However, this should not be the only means by which the decision is made. Technical personnel should be only one voice in the decision-making process; the faculty and students who are the users of the technology should hold the majority vote.

Because each institution has its own needs, requirements, and resources available—all factors in the choice of technology—there can be no standards for selection that cut across all situations. However, some common elements need to be considered regardless of the specific needs of the institution, its faculty, and students. Lawrence Tomei (1999) divided the common elements into three broad categories: use of technology, infrastructure, and instructional strategy. We consider each category and provide some questions to assist in establishing strategies for technology selection.

Use of Technology

Purchasing computers and software without a sense of how they will be used either in or to support the work of the classroom is shortsighted. We recently consulted to an institution that purchased iPads for all of its faculty and students. Although this sounded like an exciting move, when we asked them how they intended to use them, they admitted that they had no idea. They figured that they'd get to that once everyone had the iPads in hand. Clearly not much planning went into the purchase, and it is likely that only confusion will result.

Here are some questions to consider regarding the use of technology:

- How do we envision using the technology? Will we consider it to be a support to the face-to-face classroom, will it be used to deliver classes and programs, or both?

- How will the technology meet the instructional needs in our institution?

- What do we see as the implications of the technology use in our institution?

- How extensive do we expect the use of the technology to be? Will its use be phased in, or will we move directly to offering full programs that require immediate implementation?

Infrastructure

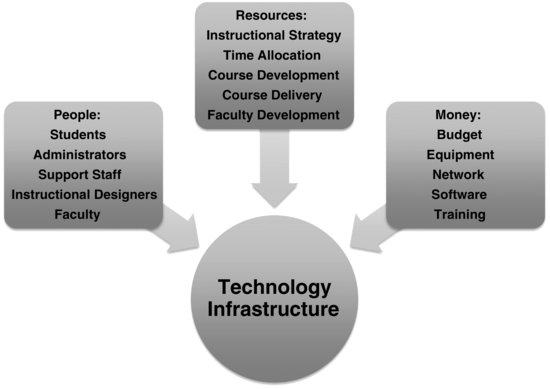

Many institutions embark on the delivery of online classes without first building a solid infrastructure to support the use of technology. The critical elements of the infrastructure are people, money, and resources, as illustrated in FIGURE 4.1. The figure demonstrates the number of influences and even pressures that converge in the decision-making process. Accounting for all of the elements helps to support a solid infrastructure.

FIGURE 4.1 THE TECHNOLOGY INFRASTRUCTURE

The people who should be considered while the infrastructure is being built are faculty, students, administrators, instructional designers (if the institution uses them), technology coordinators, and support staff. Simply identifying the stakeholders in the technology infrastructure is not enough, however. The training needs of each are also an important element here. The people and their training needs have a direct impact on the budget, or the money component, of the technology infrastructure. In addition to training expenses, budgetary concerns should include hardware and software purchases and upgrades, technical support and assistance, and incentives for faculty to develop online courses. The resources component of the infrastructure includes the allocation of time and effort necessary to make the use of technology viable. Release time for course development and delivery, and time for faculty and staff development, are important elements of the resources component. Questions to consider when building a technology infrastructure include these:

- How many faculty are interested in and ready to teach online classes?

- How many faculty will we need to train so that they can begin to develop and teach online classes? What levels of training do we need to provide for users (from novice to experienced)?

- How do we intend to provide training for faculty? What will it cost us to deliver training on an ongoing basis?

- What are student training needs? How will we meet them? What will it cost us to train our students?

- Will we be able to offer faculty incentives for course development? Will faculty be expected to teach online courses in addition to their existing teaching loads, or will they be given a lighter load in order to teach online?

- How will we provide technical support to both faculty and students?

- What kind of technology budget, in terms of both money and time, can we expect to develop? Will the institution support an expenditure for technology on an annual basis? If so, what will it look like?

Instructional Strategy

As we have been emphasizing, decisions about curricular direction and learning objectives must precede those about the use of technology in teaching and learning. If hardware and software are selected without a good sense of the learning outcomes the institution is hoping to achieve, there may be resistance to the implementation of technology in the curriculum and poor use among the faculty for both the creation and delivery of courses.

We once worked with a small college that had received an endowment from one of its alumni that was earmarked to purchase technology for the school. The school invested in smart classrooms, computer labs, and other forms of technology without involving faculty and students in those decisions. The outcome was faculty resistance to incorporating technology into the delivery of their courses, minimal to no use of the resources available, and frustration on the part of administrators. There had been no discussion of the learning objectives that the use of technology might serve, and resistance was the result.

Once decisions about learning outcomes are made, appropriate choices of technology as a tool for learning and a vehicle to achieve outcomes can then follow. Discussion of how students will be evaluated should also be included during consideration of instructional strategy, because that has some influence on the technology chosen. Questions to consider in the area of instructional strategy are these:

- What programmatic, course, and learning outcomes are we attempting to achieve?

- How will technology assist us in achieving these outcomes?

- How will students' learning outcomes be evaluated? How will the technology selected assist us in evaluating students and their achievement of learning outcomes?

Planning is clearly the key component to an evaluation of technology purchases. It often appears that the rapid movement in the direction of online learning has sacrificed a good comprehensive planning process. However, nothing substitutes for a well-thought-out, comprehensive, inclusive approach that offers time for input from all stakeholders. Many of the institutional concerns that have been expressed about faculty resistance to teaching online can be overcome with good planning processes that allow them to have a strong voice in the technology that they will be expected to use, training in how to use it, and support once they begin to teach with it. In addition, planning and budgeting for a strong infrastructure to support an online learning endeavor can help to sustain it. Cutting corners in these areas amounts to nothing less than self-sabotage and needless expenditure of money. Obtaining the money to invest in online distance learning is a concern for many institutions. Consequently, we now turn to a discussion of means by which institutions can offer online courses when money concerns are very real.

When Money Is an Issue

Many smaller institutions are finding that the purchase and maintenance of hardware and software for online learning can be costly. Although the cost for a license to download and run course management software may not be exorbitant, particularly if open source options are chosen, technical personnel are needed to configure and install it and provide ongoing technical support. There are also some course delivery vendors that do not offer the purchase of a license but instead require that institutions pay a fee for course development and hosting in addition to paying per student. Many institutions lack the budget or ability to purchase servers and licenses for software, hire support personnel, or pay high fees to a company that is willing to host and maintain their courses. How, then, can these institutions offer online options to their students and do so within their means?

Luckily, many low-cost or no-cost options now exist. Termed “open source,” these options are often free downloads or provide the ability to create and access courses on a server that is not hosted or supported by the institution.

Another solution is that many textbook companies are providing digital versions of their texts with accompanying materials and exercises, as well as communication tools. Access to the materials is generally by subscription or an added cost to textbook purchase. In addition, the Web 2.0 technologies we have discussed are options. In order to enter online teaching, then, money should not be considered an obstacle.

Accessibility Is a Major Concern

In contrast to financial concerns, access and accessibility issues are significant in online learning. Access can be a problem for students who own an older computer or own no computer at all. In addition, accessibility can be an issue for people with disabilities. Many mistakenly believe that computer technology serves all people with disabilities equally well. However, the use of computers is predicated on the ability to read what is on a monitor and type on a keyboard, watch video presentations, listen to audio presentations, or participate in synchronous sessions that involve both audio and video. Not all disabled people are able to accomplish these tasks. Assistive technologies exist, such as screen readers and voice-activated software, that are designed to help people with disabilities of varying kinds to use technology and access the Internet. However, this does not ensure that a website or course site will be accessible unless it is constructed with accessibility in mind. “In reality, an increasingly sophisticated Internet, one rich with graphics, multimedia clips and compressed text, has meant a less accessible Internet for the disabled” (Strasburg, 2000, p. B3).

Coombs (2010) notes that instructors do not need to be familiar with assistive technologies, but they do need to be familiar with principles of universal design, which allows for the greatest level of use by all users. These principles, which can be found on the website for the Center for Universal Design, include these components:

- Equitable use, meaning that the design should be appealing to all users

- Flexibility in use, meaning that the design accommodates a range of preferences and abilities

- Simplicity and intuitiveness, allowing users with all levels of experience, knowledge, language skills, or concentrations to use the site

- Perceptible information, that is, communicating necessary information effectively and easily

- Tolerance for error, which minimizes the potential for accidental or unintended actions

- Low physical effort, allowing users to move about easily and with minimal effort or fatigue

- Size and space for approach and use, allowing all users access to all components regardless of their body size or degree of mobility as well as accommodating assistive technologies

Designing online courses with these principles in mind can provide the highest levels of access for all students, not only those with disabilities, and thus are simply considered good practice.

• • •

Again, it is important to note that technology needs to be treated as just another learning tool. It is only a vehicle to meet learning objectives. When viewed in this way, the needs of the learners are kept primary, which is as it should be in the learner-centered online classroom.

- Choose technology for an online course with the learner and learning outcomes in mind first. Instructor or staff needs should come second.

- Do not use a technological tool simply because it is available. Use tools only if they serve learning goals.

- Synchronous tools or the use of lecture capture is neither the best way to deliver content nor the worst. Use these options judiciously, cautiously, and with specific learning goals in mind so as to increase access for all.

- Evaluate and adopt a course management system based on programmatic and learning goals, not sales hype. The system should be easy to use, transparent, and predominantly in the control of the instructor or an instructional team.

- Be wary of systems that promise “total solutions.” If the technology is not under the control of faculty and the institution, concerns ranging from the ownership of intellectual property to the flexibility of use can arise and become problematic.

- Allow faculty to augment the course management system with Web 2.0 and mobile tools to increase flexibility and levels of student engagement and assist with achievement of learning objectives.

- Include faculty and, if possible, students in evaluating and choosing technology for the institution. This not only helps to increase a sense of ownership and buy-in but also is more likely to result in a choice that more closely aligns technology use with learning objectives.

- Above all, keep it simple. A simply constructed course site with minimal use of graphics, audio, and video is more likely to be accessible to all users and cause fewer problems in the long run.