7. Dealing with Those Pesky Finances

Making good decisions with the money you have will better prepare you to secure the money you need and want. When you steward your finances well you’ll be able to focus on growing your creative business.

Creative at Work Justin Van Leeuwen is an Ottawa-based commercial and portrait photographer.

Web: www.jvlphoto.com

Twitter: @justinvl

I made my first couple of years of high school a lot more difficult than they needed to be, and for that I blame the emergence of rap music and the confusing fashion trends of the late 1980s. A couple of years earlier at my first school dance, I had discovered that girls like to dance with boys; in high school I thought I’d found my groove in the poetic raps and fluid beats of Maestro Fresh-Wes and MC Hammer.

When I moved from a small town to a bigger suburb I broke into my new high-school scene by teaching myself how to hip-hop dance. I wasn’t very good, so my career was short, but it was my wardrobe that caused the most social damage. In order to look the part, I decided to wear pants that had a very low inseam; these were not available locally so my mother graciously offered to make me a pair. Next came the black, collared shirt with white polka dots. I finished the outfit off with a “Fiddler-on-the-Roof”-esque hat turned backwards (so that it looked like a beret) and I strung a United Colors of Benetton cologne bottle around my neck. (I thought wearing a clock like Public Enemy hype man Flavor Flav would be trying too hard.) New friends were hard to come by, and the snickers and jeers were not as polite as you’d expect from Canadian teenagers. Most tragically, the girls were nowhere in sight.

Creative people often feel like they’re the misfits in the marketplace. Inspiration and creativity will never align perfectly with the dollars and cents that underwrite creative efforts; you need to know how to make good decisions and take fewer financial risks.

Risking It All Without Risking Your Future

It’s an exciting thing, getting paid to be creative. To put your skills and passions on the line in exchange for real money—the kind you can use to pay bills, buy that shiny piece of gear, pay for that vacation you always wanted—is an exhilarating experience. The vision of vocational independence and financial security is intoxicating. The single biggest threat to this dream of yours isn’t the mysterious forces of the market; it’s being immature with your finances. Unless you want to carry around a 500-pound cologne bottle of shame around your neck for the rest of your life, it’s time to set some ground rules, or make a change, so you can make good decisions about how you’re going to spend and make money (yes, in that order).

When it comes to your art, producing mediocre work is risky. When it comes to your business, neglecting your finances is just as risky. I’m not suggesting that becoming a financial wizard should be your goal, or that you should become a slave to your bank statement, but if you were to make just one decision, or one change, right now that would have the biggest impact on your chances for success, it’s this: Take your financial well-being seriously.

Your finances are made up of dollars and cents, the ones you spend and the ones you earn. It’s significantly harder to earn money as an independent business owner than it is to spend it. The imbalance is primarily created by the amount of energy you spend on both sides of the proverbial coin. Securing new work takes calculation and diligence, and fulfilling it takes hard work. By contrast, you can purchase new gear rashly, self-indulgently, and with ignorance as to its impact to your bottom line. The rationalized expense is the most dangerous. You know the one: You feel compelled to drop a bunch of money—usually money you don’t have—on something you think you need to get to the next level. Or maybe you just think you’re only a couple of new projects away from covering that expense. Sending these messages to your brain tricks you into believing your own lies. Try making it harder on yourself to spend money because that increased resistance will serve you in the end.

Starting a creative small business as a way to get yourself out of debt is not a good idea.

Debt-riddled ventures put undue pressure on your craft and assume perfect market conditions for your start-up. Should you find yourself in a worsening debt situation, the best action is to seek a financial counselor or a debt counselor. Reach out to a professional who can help you determine how you got into debt and what behavior you can change to reverse the trend, as well as help you build a plan to deal with your debt (and keep yourself accountable to it). If you’re not willing to deal with your debt, any other aspect of your business development will be in vain. When it comes to spending, hear my plea: Don’t spend in hope of a windfall. It’s like walking down the street in hope of finding a bag of cash or winning the lottery. Visions of a distorted reality, of some outside force solving your problems, are not the kind of hopes you should build a dream on.

I get a kick out of the phrase “time is money” as the justification for spending money. Rich people, not emerging sole proprietors, can say that and get away with it. For the rest of us, that adage holds true only if you can make more money than you spent while someone else was doing the work. If not, you have to suck it up and spend the time. Money is money. Save it. Live on the cheap. Make do with what you have and relish in the lameness. Put money in glass jars in your cupboard. Cut up your credit cards. Whatever. Get tough on your spending and your business will thank you.

And with respect to the Tax Man, don’t resent him; it’s your job as a citizen to pay your taxes. A lack of cash is an understandable reality of starting a new business, but the government won’t be understanding, so make a habit early on in your business career of setting aside a healthy portion of each billing in a separate bank account, and treat that as untouchable money until tax time arrives. Creditors, by and large, are more forgiving than government tax collectors. If you have to get creative with how you spend the money you have (or don’t have), just make sure your taxes are at the top of the priority list. If you’re curious as to how much you should set aside, from what I’ve seen, if you’re not setting aside a minimum of 20% of each and every payment you deposit, you very well might have sticker shock at year-end; if your business expenses are high, you might have a nice pile of money built up.

Though a financial professional would be the one to answer your specific questions on what is or isn’t a legitimate business expense that you can write off on your taxes, I think a general definition will help here. Reasonable costs that you incur in order to earn income usually qualify as legitimate business expenses and can be deducted for tax purposes. Personal expenses, like costs associated with living and dwelling, are not related to the business, and thus cannot be deducted for tax purposes. If you’re a shoebox keeper—as in, you chuck your purchase receipts into a pile and sort them out at the end of the year—stop it. Seriously. Make notes on the top of each receipt (so you can remember what they are for) and, at minimum, use monthly envelopes to get them organized in some form or fashion. Categorizing them further is even better. With a little paper flow you’ll decrease your stress exponentially.

For your small business to function as a business, it needs to make money. If you just want to be creative, pursue your art as a hobby and, if you can occasionally get paid for it, do a little freelancing for fun. It’s not a matter of labor hours; it’s a matter of intent. You define what you do. Your work doesn’t define who you are. You have to make money in order to eat, sleep, and dwell, so don’t let the origin of a paycheck distract you from working your way into self-employment. Try to have a job that gives you the flexibility you need or access to opportunities you can leverage down the road. If your current job is too intense and sucks the life out of you, switch jobs, or move to part-time if your business income justifies it.

Making the jump to self-employment usually requires a financial buffer, and a day job can do that. Money in the bank is a buffer that too few creatives employ. It minimizes your launch risk. Having a minimum of three months worth of your previous salary saved up should make for a fair transition. This option gives you the most time possible to get organized, get working, and hopefully put some good building blocks in place to start working towards a sustainable business. Of course, a spouse or family member can provide that buffer too, but put a timeframe on your dependence on their support in order to prevent loved ones from resenting your freedom as they slave away at their job.

Despite your insatiable need to have a clear-cut timetable for when you can or should stop holding down secure employment in favor of working more on your sole proprietorship, I’m sorry to say, there is no magic answer. But going cold turkey doesn’t work. If you’re already limiting your discretionary spending, you’re on track. If you’re making at least some money outside your business and you’re able to bank it instead of buying more stuff, you’re making the jump to full-time self-employment easier on yourself. If you’re turning down work or lucrative opportunities on a weekly basis, the proof is starting to whip itself into pudding. Only you can determine the timing, because only you can decide how much more time you need to tackle business-building tasks. One thing I’m certain of: Being a creative in the marketplace is a very unlikely way to get rich quick, so if you need to hit the reset button, or take a second or third shot at breaking free from your day job, it’s all good! Seriously. You’re not alone—keep on keeping on!

Creative Work: Brihadeeswarar Temple in Tanjore, Tamil Nadu, India (2009). Photograph by Piet Van den Eynde while in India during a one-year bicycle trip through Asia.

Building a Pricing Strategy

If I had a nickel for every time a creative asked me “How much should I charge?” I’d be rich—or at least I’d have my coffee budget covered. The short answer is not an answer at all but another question: “How much are you worth?” For the most part that’s not for you to decide. Your market, whether it’s local or national, is somewhat self-regulating (as Adam Smith explains in The Wealth of Nations); you won’t be able to simply pick a big number and pull it off. High-end pricing comes further down the road. My concern for emerging creatives is that big numbers are harder to ask for and so the race to the bottom takes precedence.

Assuming that you have your fair share of competition with respect to technical skill, it’s the other pieces of the pie that start to play a role. Your experience, uniqueness, endorsement by others, and professionalism, in that order, can and should have an impact on how much you charge. You have all of these things early on in your business venture, but they’re not as developed as they will be later on. Newly independent creatives across every discipline struggle to determine their market value because they try to set a price without any evidence or conviction. You’ll get stranded on the dance floor if you don’t know how to do the price dance, and keeping it simple is always the best way to go.

Your primary task is to remove the guesswork by determining your base price. This is your “out the door” fee, the default price that you work off of when considering a project. It’s not your minimum, which should be lower than your base price. Your base price is an average rate or simply an amount you’re comfortable with; you should be able to easily describe, in general, the benefits and basic deliverables associated with your work. From this point on, based on the project specifics, you attach dollar signs to the variables, such as add-on services and unique specifications in scope. Then, and only then, can you add project expenses. Itemize your expenses in your quote or proposal, or hide this itemization from your client if you like, but account for them nonetheless.

Industry association stats and pricing guidelines can be helpful, and peer advice is even better, but it’s hard to acquire it. To be honest, setting your base price is mostly arbitrary. Pick a number and go for it, and then adjust it from project to project as needed.

This is just a sample. Come up with your own baseline pricing matrix so that you can take the mystery out of quoting your first few jobs to get the ball rolling.

Lots of creatives publish their prices online. This isn’t always a bad idea, but caution is required. Publishing pricing on your website attracts clients who shop for creative services based primarily on price, and that may not be the kind of client you want to attract. Err on the side of not broadcasting your price so you can learn more about a project before the buyer starts setting their expectations about how much you’ll charge.

The idea of the base price shouldn’t be confused with a day rate. John Harrington, in Best Business Practices for Photographers, 2nd Edition (Course Technology, 2009), warns that day rates should be “banished from your lexicon as your bell bottoms and bleached jeans are exiled to your attic or jettisoned to a landfill.” Though directed at editorial photographers, his advice applies to many types of creative service providers: Pricing your services based on a day rate, like an hourly rate, implies that the value is in the coverage of time, instead of whether or not the objective has been accomplished or the quality of the work. Sometimes, you can account for your time in such definitive terms, and in some industries it’s very much the norm, but consider alternative revenue models if you can. Fashion tips aside, John knows what a lot of creatives ignore—that your creativity has unique value.

The good news about pricing is that there’s no easy answer. If there was an easy answer, everyone would charge the same thing and your creative soul would be on the butcher block, sold by the pound. Creative services do not generally serve anyone when there’s just one price. With inflexible pricing and deliverables, you either force your client into contracting for features they don’t want, or fail to extract the kind of value you need from the opportunity. When selling creative work, a rigid price can work for a specific period of time, but based on good or bad sales results, you should experiment with increasing or decreasing your base price until you have closed deals. Alternatively, creatives who make up numbers on the fly and answer the “How much?” question on the spot are exposing themselves to the anxiety and awkwardness that ensues. Your price says a lot about you, but how you deliver the value behind it says even more.

Many service providers, when they set their pricing, tend to “pad” a quote. It’s not as deceptive as it sounds, but it should be done carefully. First of all, it’s a practice that should not come as a result of wizardry or deception. Unceremoniously increasing your price without adding value means you’re trying to trick your clients. If you feel compelled to do that, you’ve either underprepared your base price or you’re trying to gouge them. Secondly, it’s a method that zaps confidence in your price and sets you up to fail if or when a client pushes back on pricing. You can’t back up that increase, so you’ll lose that extra money and you will have lost face in the process. Padding works only when you’re creating a buffer in which you’re anticipating or planning for some unknowns, like a contingency. In this case, rather than simply puffing up the price indiscriminately, consider itemizing it on your quote and make it a term that can be dealt with at a later time.

As a creative business grows, so does the sophistication of pricing. Alan Weiss challenges consultants and business-building service providers to change their paradigm with respect to earning money in his book Value-Based Fees: How to Charge and Get What You’re Worth (Pfeiffer, 2008). This is an intense book, and I guarantee it will push you out of your comfort zone, but the days of the hourly rate are gone, project costing is the norm, and the concept of getting paid based on one’s contribution is the future, at least for some. If you contribute to strategic planning, business development, branding, or product creation, give yourself some crazy homework and give it a read.

As for working free or on the cheap, free is the new F-word and cheap is its trashy cousin.

Doing free work for an unsolicited consumer means agreeing to devalue your brand. If this prospect isn’t on your hit list or a strategic part of your marketing plan, politely let the opportunity pass you by. If they’re approaching you, but they are an ideal prospect, it’s still a bad idea; all you’re communicating by taking the free gig is that you’re not a service provider, you’re a doormat. Free gigs rarely yield great opportunities, and every time you take one, you will have given away a piece of your soul and your time and energy will be maxed out, making your paying work suffer. That’s not good business. The only exceptions are personal projects or charities that you pursue (versus being asked to donate your time or do something on the promise of payment down the road) and collaborative projects that have clear marketing or creative value.

When it comes to accommodating budget constraints, if a potential client says they have no budget, know this: They’re wrong. Everyone has some sort of a budget. It may be very small, but there’s always something; otherwise, they wouldn’t be operating themselves. And when it comes to offering discounts, only do so when you can add terms and conditions that favor you, that make the work easier or more enjoyable for you, or that ensure you realize an opportunity you can leverage as much as possible. Provide discounts when you know it will actually make a difference to the big picture (i.e., more work down the road, increased client satisfaction, and a better working arrangement for you). And don’t offer a discount without bringing special attention to it. I’ve hired a lot of freelancers over the years, and when they give me discounts I’m not expecting, I’m embarrassed on their behalf because they just paid me to hire them.

Another form of zero-dollar pricing is quite misunderstood. Contra deals are a barter arrangement, where you agree to exchange goods or services with another person or company without money changing hands. It’s an age-old method of commerce: You do something and they do something of equal value. With creative work the standard rules pretty much apply except when you are offering innovation.

Side projects that don’t affect anyone’s records have a way of skewing not only your Cost of Business (COB) but also the time and energy you spend operating it. The casual contra deal is a very attractive method of getting something you need but can’t, or don’t, want to pay for; however, unsigned, non-contracted, or otherwise unconfirmed work effort produces a lot of variables, the least of which is that you end up providing more value than you get back. As well, when you look back and assess your revenue performance, the work and your expenditures aren’t reflected. Creative small business owners should consider formalizing all contra deals by exchanging zero-balanced invoices. Based on the type of service or goods exchanged, there may be some tax implications, like unequal valuation, so a quick discussion with a financial professional is always a good idea when doing this the first couple of times. Doing this protects you from being taken advantage of, and clarifies your contribution and its value so that future deals, especially paid ones, produce expected numbers.

Asking for Money

When you send a request for money, you should get paid. Too many creatives assume their clients are uncomfortable spending money, just as you’re uncomfortable asking for it. I’m here to tell you, that’s not the case.

Before work begins on any project, you need to discuss the price and the payment terms. A contract will often clarify this, but in some cases there’s room for interpretation, especially when a work effort doesn’t involve a proposal process. Enter “The Estimate,” a powerful document that can be short and sweet but acts like a pre-invoice that states the basic financial details of the project and clearly itemizes the terms of payment. Decision-makers love, and need, this kind of paperwork because it removes the mystery of the engagement and prepares them to do what you want, and that’s to pay you. An estimate calms the waters and gives both you and your client the chance, upfront, to agree upon the financial components, and it saves you that awkward conversation about money at the end of the project, especially if the work effort went differently than planned. Save yourself the trouble and get approval on an estimate before you move forward on any creative work.

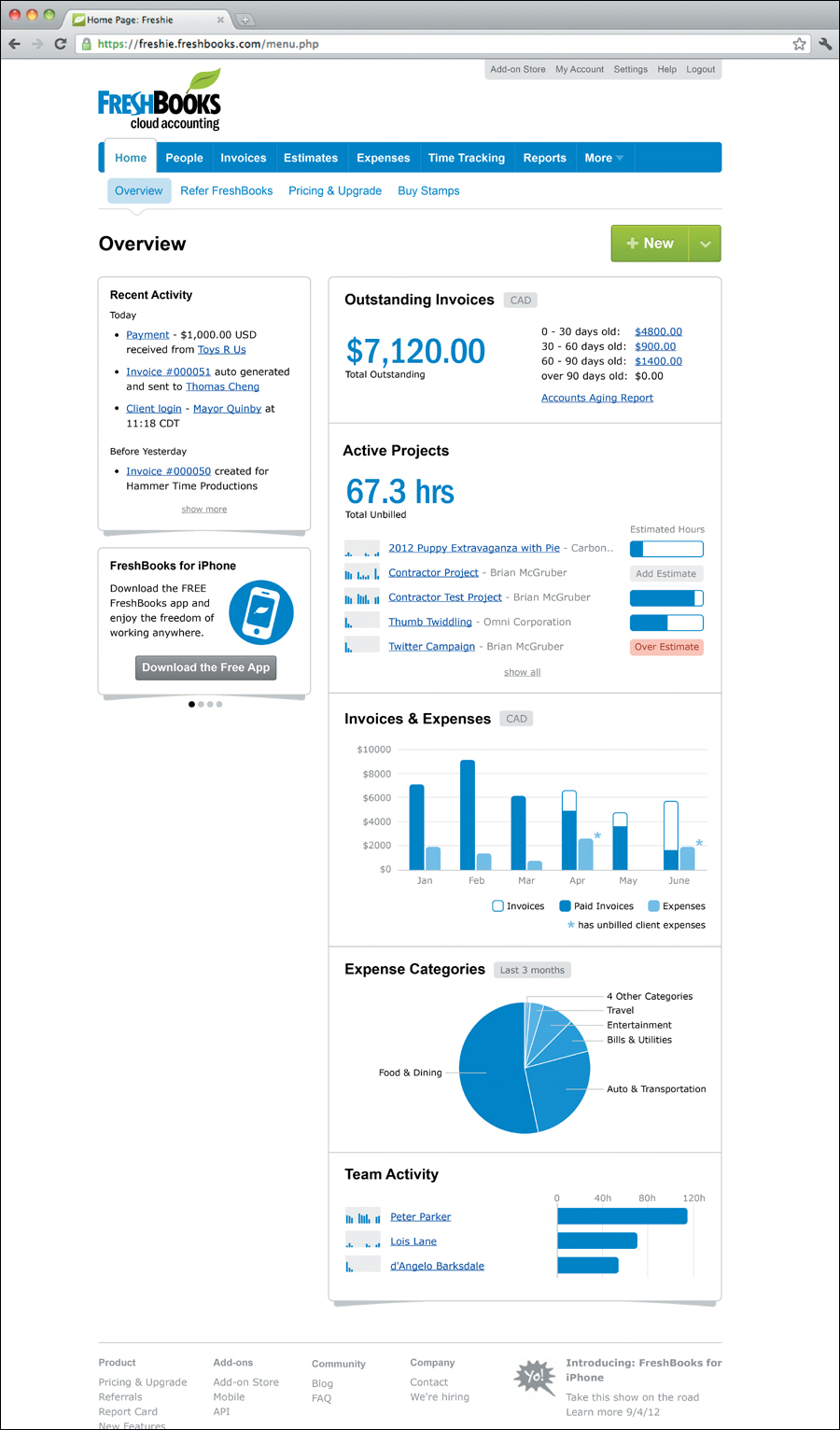

The best way to move forward is to send an invoice. I realize that with over 4.5 million users I’m not singing a new tune here, but FreshBooks.com has revolutionized the way creatives manage their time, expenses, estimates, and invoices. This web-based service has a user-friendly interface and an iPhone app that works seamlessly. Even though I love this tool for a number of reasons, they all pale in comparison to the real reason: FreshBooks users get paid faster. My clients and I can attest to that; in fact, FreshBooks states that their users receive payments 11 days quicker than the average. If you want to stop chasing clients and get paid sooner, send a professional invoice digitally, on time, and to the right person, so you can make that trip to the bank before your rent check bounces.

If you’re creating invoices from scratch in a text editor, retyping client addresses, or calculating totals or tax on your own, you’re ready for a change and your clients will welcome it. Erroneous invoices create unnecessary stress on a business relationship, and a structured, simple system like this really helps the cause. Clearly I have a crush on FreshBooks. They even have Certified FreshBooks Beancounters you can reach out to if you need specific help with your business. There are lots of features I won’t get into, but here are a few that stand out to me:

• You can give your clients online access to any invoices, estimates, or time sheets you wish; buyers love being able to check in on the financial status of a contracted project.

• You can use the “Pay me now!” feature to enable your clients to pay instantly using PayPal (or one of 11 other integrated payment gateways), which means you can pass along the convenience while collecting payment instantly.

• You can find out who owes you money and how much by signing up to receive email reports. And you can remind your clients that they owe you by automating late payment reminder emails.

Another awesome site that I’m compelled to tell you about is Kashoo Online Accounting. This web-based tool is a double-entry accounting system that follows the rules of GAAP (generally accepted accounting principles). They also have an amazing iPad app. So, for all you QuickBooks or Simply Accounting users, or wannabes, this is right up your alley. Kashoo.com takes care of invoices expense entries, and it can automatically import all your bank statements for that ever-enjoyable reconciliation process. Though it’s a full-service system, it also integrates with FreshBooks to provide a great step-up option as your business grows. When it comes time for your accountant to take care of your tax preparation, everything is in perfect order. This makes your accountant happy and saves you money.

The Freshbooks Account Overview provides a quick snapshot of what’s happening with your billings and expenses; a perfect view for a quick check-in.

The Kashoo system has a great QuickView Dashboard too – see, tracking your money doesn’t have to look scary.

If you’re looking for a really light touch, Mint.com is a free web tool that helps you understand your personal finances.

If you need to prepare a complicated quote or invoice for large creative undertakings, like big photo shoots or film projects, Blinkbid.com is a great software package that has stood the test of time.

Borrowing Money and Making It Count

You can’t always build a creative venture on blood, sweat, and tears alone; sometimes you need to throw some money into the mix. When you don’t have the money you need to start or grow your business the way you want, you start to look to outside sources. Some have the option of approaching family—or, dare I say, friends—but the most common place to look is your bank. The remainder of this chapter is based a conversation I had with my banker about how small business owners can increase their chances of getting the financial support of a bank. The most important thing I learned is that securing financing is a slow dance, and most people don’t bring much to the dance floor.

Seeking financing to cover nonbusiness debt or to subsidize one’s start-up salary is like trying to learn how to break dance in 10 seconds or less. It’s not going to happen, and you’re going feel embarrassed for trying.

When looking to borrow money, begin by approaching your own financial institution. Regardless of your banking history your bank is your first stop, because if you walk across the street in hopes of starting fresh, the bank you approach will likely want to know where you came from and they’ll start digging. Transparency is the foundation of a lending relationship, and banks take their relationships seriously. Their goal is to make money, and they want to lend money to those they trust. So give your bank the respect they deserve and approach them first. Your primary goal is to build a great relationship with your banker so that they can present your loan application to the bank with confidence. A banker’s personal endorsement plays a very minor role in getting you a loan, but it’s something you have control over, and building good rapport could be the tipping point. In a sea of red tape, you’ll want all the help you can get.

If you’re not happy with your financial institution, move your banking elsewhere and build new relationships. But don’t expect to be able to “shop” your business idea around as a way to secure financing. It doesn’t work like that.

As you find your financial groove you’ll start to find a rhythm that will relieve stress and help propel you to more rewarding work. Regardless of how much or how little you have, managing your money well sets you up for success no matter what moves you make.

Creative Work by Joey armstrong—photographer, coffee drinker, and food blogger from Vancouver, Canada.

Web: www.joeyarmstrong.ca

Twitter: @joey_arm_strong