CRAFT WITH

Networks of artisanal production

made relevant to modern markets

1 CRAFT WITH

![]()

Once in a city faraway in the desert, all was not well in the market. The craftsmen who made all the lamps and pots and rugs and cloths and jewellery found that local people were buying there less and less. Perhaps they preferred plastic and metal foreign goods, like they saw in the American films? The market stalls made the goods cheaper. They even started making copies of the imported goods. But this just seemed to make things worse. And as the craftsmen didn’t do so well, the other businesses around didn’t do so well. And then people bought even less.

One day, a man came to the town. He had grown up there as a boy but then lived in faraway lands making his fortune. He was sad when he saw that the craftspeople had so little work, as he loved all their products that reminded him of his happy childhood.

So do you know what he did? He opened a hotel. It was lavishly decorated with the cloths and carpets, the pots and rugs. The craftspeople had plenty of work here to revive their trades. And they got to make new things in new ways, to fit in with his hotel design that also drew upon ideas and styles he had met on his travels.

The hotel was fabulous and became well known. As tourists came to stay, they would buy crafts from the market to remind them of this charming city. And the local people too, seeing all those crafts in such a stylish modern context, started to be proud of what they made again and started to buy them too.

![]()

These stories are about bringing artisanship into the 21st century. Craft is something the Interland was well known for historically. Now, producers with a feeling for craft are creating customized but scalable systems of production and design to revive this for today. Case stories include: Karen Chekerdjian whose designs fuse industrial modernist styles and handmade craft; Timur Savci, producer of Magnificent Century, a hit TV show in 43 countries; Demitri Saddi, founder of .PSLAB that does for lighting what couture does for fashion; and Nevzat Aydin, whose food ordering system has brought modern online search, service and support to one in seven restaurants in Turkey.

What follows are a series of interviews with people who are passionately connected with their craft, their work process, their business. Creating to standards (not of popularity, or recognition, but truth); what one calls “sincerity”. Another explains that they had to go after awards to reassure international clients that they met safety and quality standards. An instrumental view. One not over-tainted by ego. In these stories is a first inkling of what might be different when you start outside the West, within a tradition that makes a more vital and living connection with people’s work.

I met Karen Chekerdjian in her store in Beirut. She showed me around, explaining that what she sold there was divided into “things we make, and things we love”. As we looked around, she told me mainly about the guest products, and not too much about her own. “I don’t like to talk so much about my own work,” she said shyly.

I think what broke the ice was when I picked up a brass casting of what looked like a flint stone. Turning it over in my hand, feeling its weight, its coldness, its edges, I told Karen that I had once written a paper (studying for a masters in Jungian psychology) about what I called flint think, which was the set of intuitions that we must have inherited from the two million years of human evolution when our ancestors worked on stone tools. Like the feeling a beaver must have for its dams, or a bird for its nests.

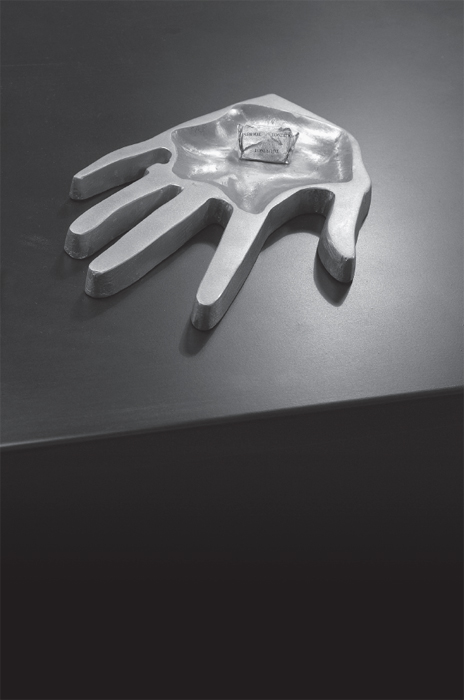

“That’s exactly what the range is about!” Karen exclaimed. “I would love to read that!” We talked about the brass flint, and how that feeling of working with our hands helps us to “grasp” things. Karen showed me across the other pieces in the Archetypes range. She told me that the first one she had designed was the cast of the indent made by a hand. Then she did the flint. Then a hammer (like the ones used by doctors to test reflexes), whose original Karen had found and “never knew what I would do with”.

Karen said these pieces were designed to be “tools” for a modern office; working with computers, sitting at a table, and never so much with our hands:

It’s to have something in your office that reminds you. Tools you can get out of the box and put on the table. You feel attracted to touch, to feel the material. They are tools you probably won’t use in a literal sense. But they ground you. You feel something. You connect to the earth. Everything today is so unreal, so unrealistic. Tools were the first object that mankind created.

We talked about that same need perhaps being why iPhones with touchscreens had proved so popular. Because they drew on an innately human way of touching an object. “You can give a baby an iPhone.” said Karen.

At another point in the conversation, when she was talking about her early career with high-end design brands in Italy, Karen said “I am not a tool”. She was explaining how others around her were much more proficient in technical drawing, or computer-aided design. I thought it was an interesting contrast given the tools Karen had created to humanize office life. The choice was to find yourself and be fully human; or to become mechanized, spiritless, like a machine or tool in a production line. It seemed like Karen had made this choice, long before creating that brass flint.

Karen’s passion, she told me, is storytelling. You hear that word a lot around design these days, but – like the tool/tool dichotomy – what Karen meant turned out to run deeper than most (who often mean just an elegant way of selling design). Her dream had been to become a movie director. She had come close to breaking into the movies, but then fate had intervened. So now she put that impulse into her design work. “Every time I start a new project I have to tell the story. The material I use. An encounter. Some random thing that becomes the story of that object.” We talk about the way that mass-produced goods that are all the same can become alienating. “I think they have no spirit,” Karen says.

All of Karen’s designs are handmade. She told me that originally this was simply because she had no choice. When she worked in Italy she had access to high-tech manufacturing. They could make almost anything she could imagine. Back in Beirut, if she was going to manufacture, she would have to work with local artisans. Over time, this had created something unique, and really important to her, “so my curse became my blessing”. If she had not come back, she would probably still be designing in identical ways to her friends in Paris and Bologna, part of a system and not developing her own way of working, finding herself in her work.

Not only was it an opportunity for her own design vision to branch out, but Karen saw she could “give the chance for these craftsmen to have a new life”. But it had been a struggle, she told me. And it still was whenever she worked with new craftspeople. Karen told me about working with the brass caster, who used to make traditional items for tourist shops. “I told him now you have to forget everything you have done.” She pointed to the tray our coffees had come on as an example. They looked completely bare. But when I picked up my coffee later, I noticed there was a single bird engraved at the centre; looking like a French naïve “oiseaux” illustration. Karen’s tray had a fish.

For him that was nothing. Usually a tray had to be completely engraved with sentences from the Koran, with drawings, flowers. I wanted no engraving at all. The guy thought I was crazy. It was a three-year struggle to make him follow me. Now he thanks me for pushing him further, getting him to try new things; to think different.

Karen Chekerdjian had changed her approach too, with that long slow process of collaboration leading to new understanding on her side of working with real materials. Sometimes she had found that her ideas just couldn’t work. For instance, her perforated sheet metal screens lacked strength, so were hard to curve well. But more than this, she learned to appreciate imperfections. “I originally wanted perfectionist objects. But when they are hand cut and handmade from wood they are never perfect.” She showed me the organic line of a join in the table we were sitting at. This had a surprising advantage, she told me – you wouldn’t hear a customer say “I can’t buy this table, it’s marked”. The objects were imperfect to start with. That was just their look. It also was “alive” she said, in the way it would age, the copper getting more “brownish”.

I asked Karen about her sense of time, how that comes into her work. She told me that she was very attracted to futuristic themes. She talked about the way the future was portrayed in a recent film Hunger Games; the fascinating way that in future cities they have to mix the gleaming technology with a bit of dirt, something gritty to make it real. In her design work, Karen said there was often something about it that looked almost retro and familiar. But when you looked close, you realized that you haven’t seen anything like it before. Or that it had been taken to a new extreme, through technical research. She described it as “winking” – something playful in the object, like the pull chain on her mushroom-shaped Hiroshima lamp, that felt almost Art Deco until you looked closer. It was a way of “taking you into” the object, starting with the feeling of familiarity, of there “being no conflict”, but then drawing you on, into the 21st century.

Karen next showed me a range of children’s toys she had designed. It had started with the large oval boxes they came in, made of what looked like plywood. Karen told me they were originally used for sweet pastries that she remembered from her childhood. But gradually that market had gone over to plastic containers. She tracked down one of the last places making them in Damascus (in Syria, just before the war) and she felt she wanted to give it a second life, so on an impulse she ordered some. Given the connection with her own childhood, she decided to create toys to go in the boxes. The first toy set called Adam’s came about by accident, when a friend’s young kid was visiting and Karen gave them some wooden blocks that she uses to hold display placards to play with. These worked great as toys. So instead of painting the blocks, she ordered them in different woods; sycamore, beech, oak, mahogany and ash – and also different shapes – cubes, cones and cylinders and so on. By having much less to them than most toys, they leave more space for imagination.

My favourite toy, though, was Beit Claire, the tablecloth at the other end of the table where we were sitting. Hanging to the floor on three sides, it was an off-white cloth printed with thick ochre-coloured lines, in a naïve style, to look like a play house; with the window cut out in a square so you could look out. If you climb under the table, you find that inside the cloth are printed a stove and other play house images. On top are drawn some place settings so that after having your friends over to play, you can have tea together. Karen told me that Beit Claire was the result of thinking about “how to get a house into a sweet box”. And the inspiration came from remembering how “children love playing under tables”.

That’s the kind of insight that gives Karen Chekerdjian’s work such warmth. The style and materials can be modernist, almost industrial. But there is that spark of recognition when you see someone has had the same idea as you. Like the spark of recognition I got when I picked up the flint. Perhaps most of her customers have that experience with something in the store? Karen is making things in a way that you could describe as the opposite of “alienation”. (Could “humanation” be a word?)

Karen Chekerdjian is using storytelling as a structuring intelligence to guide her intensively crafted designs. We next meet someone who used craft and absolute attention to production quality to reinvent storytelling in the previously quite debased medium of Turkish television. In a way, their creative ethic is similar – guided by a strong intuition and putting their own subjective selves at the heart of the creative process. But whereas the largest thing Karen tends to design is something like a retail interior (for her glamorous neighbour, Rabih Kahrouz), our next interviewee makes lavish TV epics that set audience ratings records, and is easily one of Turkey’s biggest cultural exports.

Timur Savci describes himself as a serial entrepreneur. I think this is so much more accurate than “TV producer” as he has created new markets, products and genres, often with considerable commercial risk. I met him at his production company Tim’s. Timur told me that he started out trying to please his parents by studying to be a lawyer. As soon as he entered university, he hated it. Meanwhile, to make ends meet as a student, he embarked on a career as a waiter and also DJ-ing in clubs. He loved these side jobs more than his studies. The café he worked at was a popular social hangout for creative people. One of these was the famous writer Meral Okay, who he worked with decades later on the TV series Magnificent Century.

One day, Timur went to see his cousin on the set of a TV commercial shoot. As soon as he saw the set, Timur knew, in an epiphany, that was what he wanted to do with his life. I asked him why and he said: “First it was a very different world. Second there was discipline in it. Everyone had a role and yet it was flexible and relaxed – a bit like waiting the tables. And of course it was very creative.”

Timur hung around at the shoot all day. Then at midnight there was a crisis. The commercial was for a brand of detergent, and they needed some fabric dye. Timur volunteered to find some – “Just give me a car” he told them. He succeeded, of course, and the next day the boss gave him a job as a runner. From then until 1998, Timur worked his way up, becoming production manager and then production coordinator in that company, making movies as well as TV commercials.

At that time, Timur happened to become the production manager of a TV series called Second Spring. Timur was used to working in commercials and cinema where the production values, art direction, scenarios and stories had a developed quality. Turkish mainstream TV was, as he put it, “Indian style” – cheaply made, with poor storylines and acting, and often made by a famous singer, who also starred in the show. Timur brought a whole different production quality to this show – using a team mostly from cinema, also bringing in expensive lighting and new techniques.

At that time, Timur’s main work was still in making commercials, which was much better paid. With a friend, he had started his own commercials production company. They had a couple of golden years of success, making commercials not just in Turkey but also for international brands in Japan and the USA. Then in 2001, there was a huge financial crisis in Turkey and the entire commercials production industry simply stopped. Much worse for Timur’s company, though (because of their balance of payments in and out), was that the Turkish exchange rate plummeted. Overnight, they were broke. He couldn’t even go and work as a producer for another advertising company because they saw him as a rival. So Timur was unemployed. And he sat around the house, feeling hopeless and depressed for five to six months with nothing to do.

Then the phone rang. Based on his work on that one previous TV show, a production company wanted to hire him as a coordinator for what was (for him) a very low fee. The project at the outset looked quite low-grade creatively. “Like one of those TV productions where a famous singer is the star.” But Timur bit his lip. “I had to take the job, because I had to pay my electricity bill.”

At first, he just did the production coordination job and kept his head down. Timur couldn’t bear to tell most of his friends what he was working on because it wasn’t something he could exactly be proud of. But then before it even aired, the production ran into trouble and he was offered the exec producer job, which he jumped at. Now he could run the show. That TV show was called Lady of the Ivy Mansion and to this day it still holds the TV ratings record for Turkey.

Timur first brought a different level of professionalism to the whole production process. And with this, a raft of more advanced production techniques that were familiar from commercials production and cinema, but had never been used in Turkish TV: like commercials-style colour grading and filming with steadicam. Second, rather than shooting the show as intended in a bland location in South East Turkey, he moved the setting to Cappadocia, the area that famously “looks like a lunarscape”. Hence following how cinema enthrals its audiences by creating a unique, crafted, visual identity and setting – a life-world that you get immersed in.

At this point our translator Anil broke into the conversation to say how much she had loved the Lady of the Ivy Mansion. How amazing it had looked and how addictive it was; how friends used to tape it for her when she was living in London. Anil was fairly typical apparently. 80% of the entire country used to tune into this weekly show.

Another common factor in both this show and his previous TV series, Second Spring, was working with that famous writer who used to come to his café, Meral Okay.

Timur explained that most of his subsequent successes were based on being forced to analyze where the gaps were in the industry. He wasn’t established enough to survive without being entrepreneurial. His first production after launching Tim’s in 2006, called Daydreamers, broke new ground as the first Turkish drama made for a young audience. Retrospectively, an obvious gap. Turkey is a young country. So why force teens and young adults to sit through shows that were “made for their mothers”?

I asked Timur how he was able to spot what could be a potential hit. He told me that it was mainly instinct. Or more particularly, what he looked for was a quality of “sincerity”. What this meant, he explained, was that the feelings portrayed are sincere, that they touch you as real, true, in an intimate way. As if they know the inner you.

I see a connection between Timur’s work and Karen’s here, even though they work in such different fields. Both bring this subjective quality into their work; of life as it is lived from the inside. The audience feeling that defines such work is recognition; you recognize a part of your own inner life, your feelings in it. Like you do when you hear a song and feel that the lyrics must have been written about you.

Magnificent Century, Timur told me, represented a new stage in his career. Now he had money and a track record and for the first time had the freedom to do pretty much whatever he wanted. And what he wanted was to make something big. And different than anything on Turkish TV before. In fact, it would have to be produced for a global audience, from day one, because there was no way that the economics of Turkish television would stretch to the sort of epic production Timur had in mind.

For several years before this, Timur had been talking with Meral Okay about a creative departure for both of them – making a historical drama set in the Ottoman Empire. I asked Timur whether this was part of the growing confidence in Turkey at that time. For instance, in the UK when Merchant Ivory had been making similarly lavish historical dramas for TV and cinema, it was in the context of Margaret Thatcher, Laura Ashley, Paul Smith, British Airways and a general return to British identity. Timur said not at all. It had nothing to do with conditions in Turkey.

I asked other people I interviewed this question and they said the same thing. Magnificent Century had, according to adman Serdar Erener, been “a real Black Swan”. Serdar also told me that far from being a part of the New Ottoman rhetoric from Erdogan’s AKP, the show had led to a huge clash with the Prime Minister who publically denounced it: “This man spent 40 years on his horse, conquering,” Erdogan had complained, “not sitting around in his harem”. Timur also tactfully neglected to mention that his own government had threatened to introduce a law “banning programs that infringe on national values by insulting, denigrating, distorting or misrepresenting historical personalities and events”. So it does seem, from what I gleaned, that Timur could justly claim not to have jumped on the Ottomania bandwagon, but rather to have started (or at least anticipated) the trend.

And here comes the entrepreneurial catch 22. There was no way on earth that Turkish TV channels would ever finance such a lavish production; especially ahead of the trend that would make it so obvious in retrospect (a hit movie on the start of the Ottoman period followed, and even a Suleiman-branded property development in central Istanbul). So they had to fund it themselves. First they had to spend a year developing the storylines and scenarios. Then there was another lengthy period of research and development, working with academicians and history consultants to get every detail right in the costumes, the sets. So over this time Timur put all the money that Tim’s had made in the preceding years into the project.

I asked Timur why they had picked the story of Suleiman and Roxelana (the red-haired foreign wife, who became the Sultan’s queen and greatest love). Timur thought it came down to two factors. One was that Roxelana and Suleiman was the archetypal love story, like Romeo and Juliet; one that everyone in Turkey knows. Secondly, other Ottoman shows had looked half-baked and drab, but that period in history was the absolute height of Turkish power. It was a magnificent time, in terms of power, opulence, culture, confidence, success. So the potential was to make everything in the show – every shot, every surface, every costume – magnificent. To create an immersive world of magnificence that the viewer would be enraptured by.

Timur realized just what a risk this strategy was when he visited the sets as they were now completing pre-production. It looked like a scale of production he had only ever seen in Hollywood. It looked, in other words, incredibly expensive. At this point, Timur got the fear. He finally realized why his friends had been telling him he was crazy for the last few years. But he decided – what the hell? – there was no turning back now.

The rest is history. The show was a huge success in Turkey. Audiences were mesmerized. It was picked up in a bidding war for international rights by Gulf TV networks. And if anything, it was an even bigger hit there. It prompted national debates about whether Saudi husbands were as romantic, attentive and “magnificent” as they should be! The show eventually aired in 43 countries. It spread to the Balkans, across the former Ottoman Empire, and even beyond. When I arrived back in London, my Asian taxi driver told me him and his family were going to Istanbul for a family holiday. Did his wife watch Magnificent Century I asked? Oh yes, he replied, that was why they were going.

I asked Timur “What next?”. He told me that he was developing two projects.

One was based upon a bestselling novel called Kiliç Yarasi Gibi (Like a Sword Wound). He didn’t give many details, but I did my own research. It is another historical story, set in the 1920s. And the novel’s author, Ahmet Altan, is a controversial figure, who was fired from newspaper Millyet for writing an alternate history of Turkey called Attakurd (in which he wondered how Turkish people would react if they lived in a Kurdish country that tried to ban the Turkish language). Like a Sword Wound is not only about Turkish history, though; it is a complex love story, set in the last days of the rule of Sultan Abdul Hamid, when the Young Turks were organizing their revolution. It sounds in every way a worthy successor to Magnificent Century; something like a Turkish Doctor Zhivago.

More intriguing still, what Timur told me he believes will be “the next big trend in Turkey” is another show he has in development called 41. It is set in the present day and concerns people who have supernatural powers; “not like American superheroes” but rather with “immortal love that goes on after death”. Timur describes it as “a metaphysical drama”, strongly influenced by Sufi sensibilities, drawing on quotes and ideas from Rumi’s Mevlana.

If you were a chef, a nightclub owner, a gallery (like London’s Barbican), a hotel or a wealthy home-owner and you wanted to use light in a way that was totally unique to your space, your brand, that created a unique effect in line with your own vision… then .PSLAB might be the best people in the world to talk to.

If you were an architect trying to source some reasonably contemporary lighting installations to complement the rest of your creative concept and you wanted a flexible supplier who would work to a tight brief (or preferably just supply something similar to what you saw in a hotel once, or in a design magazine) – then forget it. From the view of that sort of architect or designer with fixed ideas, .PSLAB could be a nightmare. You’d see them as difficult to work with and potentially show-stealing.

This would never be a problem in reality because .PSLAB are very choosy and wherever possible they work directly with the end client, not “intermediaries”.

.PSLAB seem very careful about how their brand is presented and described, so allow me to quote their website:

.PSLAB are designers and manufacturers of site-specific lighting products, founded in 2004 with over 100 team members and working out of four bases in Europe and the Middle East including Beirut, Stuttgart, Bologna and Scandinavia. Our work can be found in private homes in London, art galleries in Beirut, restaurants in Rome, hotels in Paris, conceptual boutiques in Antwerp, offices in Berlin and at events and in public spaces worldwide.

We are to lighting what haute couture is to fashion – through a customized project approach we offer a complete service, which has allowed us to build ongoing working relationships with our collaborators. Our creative and technical teams work together on every aspect of product development, from concept to construction giving us the edge at the core of the .PSLAB identity. Our concepts are born out of the individualities of a space and our products conceived for specific projects, custom-manufactured by our artisans in our workshop and hand-finished with minute attention to detail.

I met with Dimitri Saddi, .PSLAB’s founder, at their workspace in Beirut. Dimitri told me that they had reached a new stage in their development. He was questioning their whole approach. Previously they had to establish their brand and reputation internationally. And they had succeeded in that: with seven Red Dot (global design) awards to their name. In that previous stage of expansion, they had to be ruthlessly disciplined about what they were and what they stood for. And so their work, their brand and all their manifestations had a tightly and centrally controlled identity. The problem was that this ran against their most basic belief which is that each solution is unique and grows out of the context, the need, the client’s vision and so on. And if it led to controlling their international offshoot offices too tightly, Dimitri felt that “this is the approach to make another Starbucks”.

There were two implications. Firstly, that they would now try relaxing and let each office develop aesthetics that responded to its local market. The second implication was to work even harder to formulate what it was in the process that made them unique: the “who we are in what we do”. This shouldn’t be confused, Dimitri told me, with other terms like skillset. It was their method of working together that had an influence on the outcome. To develop that further would mean to question some of the “invisible boundaries” that people would tread carefully around, but not cross. Dimitri also felt that now they had proved themselves commercially, they needed to be much more selective. “It’s not about producing more now, it’s about what we want to be part of.”

Dimitri Saddi showed me around because he felt that the physical space was a big part of their design philosophy. He showed me the large prototyping spaces that made it possible to do early work with physical materials rather than just on screens. And his next step, he said, was building a kitchen. I thought it was a metaphor at first. That when he talked about “teams cooking and eating together” he was referring to close-knit project work. But no, he really meant a kitchen; with a herb and vegetable garden. Dimitri felt that bringing more humanity, more social rituals into the workplace would help to break down those invisible barriers he mentioned earlier.

It wasn’t all about soft competences. Part of their proving phase had been about demonstrating they could work to international standards. They had to gain credibility for electrical safety, and quality control. No easy task as, like Karen Chekerdjian, .PSLAB had been forced by being based in Beirut to work with local artisanal production. This was a blessing in the same way as for Karen, in encouraging them to develop a unique approach. But it was also a challenge when, as Dimitri told me, some of their producers had “Post World War II” type facilities. Whereas their competitors – in Germany – would have suppliers within easy reach with state-of-the-art equipment and controls. To build sufficiently robust quality assurance systems, Saddi told me they had to invest heavily in their production facilities and the lab testing.

I was curious to know in today’s jet-set world, and with such strong credentials, why it wasn’t possible to run all their operations from Beirut. Dimitri told me that it was because they had to gain the confidence of local clients, work with them closely and collaboratively. “People have to come in and chat, touch the materials.” It was a similar point to that of needing, where possible, to deal directly with the end client. He told me it was ultimately about creativity – wherever there are distances, people are more inclined to play it safe, and they won’t take risks, even good ones. “The quality of work depends on the quality of the dialogue.” That means that their typical client was an up-and-coming brand, one that has a solo owner. They especially liked working with clients who were creative themselves; like a chef or a fashion designer.

Saddi told me he felt that there was an intimate link between the development of the company and “your development as a human being”. If you as a leader had hang-ups and barriers, so would the company. If you worked on them and grew as a person, so would the company.

My favourite bit of the tour was when Dimitri pointed out the high industrial yard wall and huge sliding metal door that screened them from the world outside. “You need a barrier between you and the outside world,” Dimitri told me, if you wanted to stay authentic: “The real issue now is you get so consumed out there. People jump on you, ravage you, consume you and then move on to the next brand.” Being authentic meant resisting that, he told me. And it meant holding fast to your own version of the world, and “not just chasing the money just because there is a market”. That’s why I suspect .PSLAB had become reminiscent of something more like a working monastery than an office; restrained, cloistered, disciplined, but inwardly flourishing.

Next to Istanbul, another highly designed office. Nevzat Aydin is one of the best-known entrepreneurs in Turkey. Not only because he has one of the biggest internet successes, with a recent investment round of $44 million from US Venture firm General Atlantic, but also for his appearances on the Turkish version of Dragon’s Den.

Nevzat turned out to be an unassuming man, quietly spoken, charming. He’s the first interviewee in this chapter who wasn’t dressed in black. A practical business builder with a real sense of humility about him, coming from – he told me – quite an ordinary background. That’s why he had taken on the TV appearances; to show by his own example that you could come from any background and create something. In his case, something extraordinary.

Nevzat had come back to Turkey in 2000, after taking an MBA in Silicon Valley. He knew that he wanted to do something entrepreneurial and had gone there mainly to “breathe the air” and absorb what was happening in e-commerce. His passion for the internet had started much earlier, in 1994, when he had done his undergraduate degree in computer engineering.

Within the tenth minute I knew I would do something with this. I was just browsing the site of Yahoo. It was all text based. You just hit the return button on links. Immediately I thought “This is going to be huge”. And the more time I spent on it, the more I thought that.

One immediate application Nevzat found was that every week there was a national newspaper competition with really obscure general knowledge questions; “And every week I was winning!”

Nevzat says he wasn’t a very good student, and hence while he’d have loved to have gone to Stanford, he ended up at the University of San Francisco. But he did manage to get some work experience at big name tech companies. And he witnessed both the upsides, like companies going IPO (making the founders a fortune through selling stock, by making an Initial Public Offering), and also some dramatic dotcom failures.

Returning to Turkey, he rejected his first three ideas – creating the equivalents of an eBay, a Match.com, or a betting site – because all of them would run up against problems with local legislation. Instead, he went for a safer a model and one very close to the Turkish heart; how to order local food online from that delicious but slightly disorganized little kebab place up the road. Perhaps one you hadn’t even tried before. The model, he worked out, could include a directory of thousands of restaurants, some information on each, all the information you needed to order, and it would also handle the transaction itself. The result was Yemeksepeti.com (which means “food basket”).

He knew that to pull this off, he would need a team. Nevzat figured what he was best at was the creativity, innovation and motivation. There were two other key parts of the business. One was IT. And while he says he is an “okay” computer engineer, he knew a much better one, who was a friend. The other key piece was restaurant relations. The kind of person who could “do cold calling and get a result on the fourth or fifth attempt”. Which definitely wasn’t him. But again he knew someone perfectly qualified. The three teamed up in September 2000, and by January 2001 the site went live, albeit with only 30 restaurants at the time. For the next four to five years they struggled with limitations. Most customers, for instance, used a dialup modem and they had to ask them to log off the internet if anything went wrong, so they could contact them by phone.

What Nevzat Aydin thinks they got right from the start (and where comparable sites in the USA went wrong) was the business model. Firstly, they never charged a restaurant except for commissions on actual orders. No fees for membership, or listings, or leads. And they never ever charged the end customer, who hence always paid the same as if they had phoned the restaurant direct. Secondly, they never went in for logistics (and hence only signed restaurants who could already do local deliveries). All they did was take and transmit the order in the fastest, most robust way, and also offered perfect end-to-end support to customers if anything ever went wrong. And looking around his office, there was a large team on the phones doing customer support. I think of it a bit like asking a hotel concierge to organize a takeaway for you.

Over that initial period, they managed to increase their daily orders fivefold, but it still wasn’t enough. Then when broadband hit in 2005-6, order numbers went through the roof. Towards the end of 2005, they reached financial break even. Today they process over 55,000 orders per day. Around one in seven of all the restaurants in Turkey that deliver food are on the site. They have launched in Cyprus. And they are launching in three or four more countries in the next six months, using the funding from General Atlantic. Plus they plan many more food-related services in Turkey.

The other key to their success, Nevzat thought, was finding a cooperative model, where everyone wins; the customers, the restaurants and his own company all doing better, functionally and economically.

What Nevzat and his team had done was create something that made existing small businesses more successful – giving them everything they needed to rival the big players like American pizza delivery chains. Their latest venture, Nevzat told me, was taking this even further, into the much more local specialities. Their new model so far only includes 50-100 suppliers that have been handpicked by food experts as offering the best of the unique regional speciality food. Hence you can order the really local varieties of olive oil – or typical dishes such as Gaziantep’s baklava or Trabzon’s cornbread that you can’t find in the big cities. Anil Altas, my translator for Timur’s interview (also a writer of books on digital Turkey), told me “even my parents are using this”.

Nevzat thought that if he had founded the company in another country, he’s not sure it would have got this far. His employees in Turkey had a particular knack for trying things, being practical, making changes. They also really stuck with stubborn problems until they solved them. And they didn’t mind adversity, struggle, chaos and setbacks – that was just normal to them. He told me about a Yemeksepeti group ordering feature that had been really problematic, so they had had to remodel it four to five times. But now it was a huge hit with university students and was on track to account for a quarter of all their orders in a few years’ time.

Just as well they were adaptable, as everything kept changing so fast. Mobile a year ago only accounted for 1% of their volume. Now it was 5% and will soon hit 20%. And – while the practical, improvisational Turkish entrepreneurial mind-set might cope better than most – things will change even faster in the future. Nevzat told me that he had been watching his friend’s two-year-old son using a touch screen and realized that quite soon new generations would be coming up “with visions that we never had”.

The model throughout this chapter is one of finding ways to connect the quality of small-scale and high-end craft quality with the design, convenience and service demands of modern consumers. While the service may include your own designs, it’s the process, the production flow, the collaboration that is critical.

They all approached this in a way that seemed very intuitive; as if they just recognized the right approach. But that’s not to say that it is unthinking. All of them had done lots of analyzing and correcting, fitting their empirical learning to the market rather than blindly chasing after second-hand fads. In an aside, Karen Chekerdjian told me that she had started out making abstract, artsy objects, like round “storage balls” for keeping things in. But she found that people couldn’t connect with them, couldn’t imagine them in their home. So she started to work instead from really familiar forms, and then let her more artistic side work on the nuances, meaning and intelligibility.

As Karen suggested, this may partly be because they have had to wrestle with the physical making of things and with local limits. Not working with concepts, but with brass. And with stubborn artisans who know how to work with brass. Timur’s craftsmen were originally drafted in from cinema, bringing a different dynamic into the flow of TV production; put together less hastily, more carefully constructed.

Discipline was also a key element of all of these stories.

I also think what Timur said about being an entrepreneur is key. They are running their own business and even when dealing with commissioning are making sure that they are wholly involved, taking responsibility for the complete outcome. While Karen talked a lot about storytelling, she also told me at points about her business; about margins, international deals, the problems of getting represented right by galleries.

The complete picture is one of work, as it should be. Not suffering from the division of labour, from client Chinese whispers, from double and triple guessing. You are then completely operating as a whole human being, taking in all of the information (with a team of collaborators) and giving a whole response.

The point that Dimitri makes about having a process, not a preconception, strikes me as incredibly powerful. As does his way of creating the interior of his company as a kind of microcosm, a world apart that can then effortlessly produce more creative, more original work because it isn’t too beholden to trends, it is authentically “apart”.

Another key theme from .PSLAB is the idea of a creative process as an open and flowing conversation. One that it’s important not to have firewalls within – such as the one that can be introduced between client and contractor or through internal “invisible boundaries”.

Authenticity is a key part of these stories – or “sincerity” as Timur put it. That’s I guess what makes all their products so globally successful too. Because in our own hyper-real societies, authenticity is hard to find, and fleeting when you do. We have so few functioning traditions and customs that we rely on the new new thing; fresh, cool, popular, a trend. A year later we see it hanging in a cupboard or parked on a driveway and it feels not so current, not so alive to us. These designers are bringing their own authenticity, vision and resistance: to create the enduring appeal of “instant classics”.

If you had to summarize what unites these approaches when it comes to the end product being so appealing, the main connection would be a dedication to craft. And a kind of intrinsic, authentic, quality that comes from a deep and full involvement of the Self. The craft takes on a modern precision, sharpness, quality – but also retains a handmade feel, whether it is Timur’s penchant for steadicam, or Karen’s love of lines that wobble slightly. But these interviewees are not the craftsmen themselves, wordlessly chiselling, turning and working their material. They are operating on a more semantic, symbolic level. And the key word for that – a word that recurred throughout the interviews across this whole region – is storytelling. Not just the abstract storytelling of an entertainer, but the involved storytelling of a participant in the drama. One, for instance, who has learned their humility and resilience because blocks or setbacks have made them change their plans.

Finally, there is the question of what motivates them to produce such beautiful products, often at great commercial risk, when their markets can have much lower standards. Obviously there is a commitment to their ideas, to what they produce having value: but not through egotism. Rather, because they have developed it with a protective respect, not to be so easily parlayed away by any idiots who don’t get it (they all told me stories of such idiots, and how they rebuked them, or walked away).

And it also perhaps comes from an unspoken assumption that the world actually deserves better than the “affordable” lazy mush that furnishes our home, lights our public spaces or fills our TV channels?

Another factor is bringing their brilliance to a humble category. TV dramas; office furniture; kebab shops; lighting. I don’t mean for a moment to downplay their work. I thought it was creatively top-notch. But it’s even more brilliant because they didn’t apply it to a world with the lazy instant glamour of fashion, architecture or cinema.

Bringing humanity to making is a big theme of the next chapter too. Only here it is about how to humanize and socialize inventions (in that otherwise soulless world of the pointless techno gadget)….

“ Its to have something in your office that reminds you. Tools you can get out of the box and put on the table. You feel attracted to touch, to feel the material. They are tools you probably won’t use in a literal sense. But they ground you. You feel something. You connect to the earth. Everything today is so unreal, so unrealistic. Tools were the first object that mankind created.”

Karen Chekerdjian

Hands On, design by Karen Chekerdjian Studio, photograph by Nadim Asfar