CHAPTER 9

INVESTING IN TOMORROW’S ORGANIZATION

In 1994, we found out that our large practice of complex knee- and hip-joint replacements lost money—actually about $2 million per year. When you are an orthopedic surgeon and working very hard and dealing with patients referred by other orthopedic surgeons, this is very difficult to accept. Partly this reflected the nature of our practice, as we do a fair number of surgeries to replace failed implants, but it also resulted from things we were doing—keeping people in the hospital too long, for instance. Most significantly, however, the loss stemmed from the implants we were using, for we were implanting 10 to 12 versions of half a dozen major designs for any one clinical indication. Clearly, things needed to change.

It is important to remember that the Mayo Clinic culture is very strong. My colleagues and I have all given up our ability to earn as much money as we could in private practice. We have bought into a culture where we labor for the common good and are focused on doing what is in the patient’s best interest. When you say to these MDs, “We have to reduce cost in caring for patients,” that flies in the face of what we are doing here.

Physicians revert to primal instincts when confronted with information strongly suggesting that they change the care of patients. They begin hiding behind rocks—the first is the data quality rock. They will argue, “Your data are flawed. Go back and look at this again.” It is a cultural expression saying, “We are unwilling to change.” So we made sure the data presented to physicians were accurate. And, since this was physician-led, it was physician-to-physician communication rather than financial analyst-to-physician. So, I was able to say, “The data are accurate, and you can’t question them. But if you can demonstrate to me that they are inaccurate, then I’ll rework the data. Lacking the demonstration, however, the data are accurate.” So, we blew up the first rock.

Then most physicians will hide behind the clinical quality rock. It is usually expressed in some variation of this message, “I’m not going to do that because I have the best interest of my patient in mind.” We needed a logical argument that enabled the physicians to see the needed change as an expression of our culture. For years we had held such a strong commitment to the best interests of the patient that there was hesitancy to question physicians’ clinical preferences when they hid behind this rock. Consequently, we’d come to this wide variation in our practice based on the surgeons’ personal perceptions of what was best.

The first step in change was to get my colleagues to accept the premise that each of 12 different prosthetic knee implants was probably not “in the best interests of the patient,” particularly when surgeons had their favorite implants and their cost varied widely. And, when we faced the losses from our practice, it seemed that cost did matter. So, as medical scientists we came to understand that variation is expensive and standardization is a way both to control cost and to improve quality. We blew up the clinical quality rock with this ground rule: We will adopt evidence-based criteria to identify what is best for patients and then choose the lowest-cost prosthetic joints that do not compromise the quality of patient outcomes. Our goal was to reduce the choice to two implants for any one clinical indication.

So, we partnered with our colleagues in supply-chain management who negotiated with the manufacturers of the implants. It turns out that we moved the net operating income of the knee and hip practice from a negative number to a positive number in two years—an $8 million swing in the Rochester practice alone. Even more important, there was no compromise in the patient outcomes; the complication rate in our patients did not change. The savings have held for a decade and been multiplied as the Florida and Arizona practices as well as Mayo Health System have adopted this approach.

This account by Dr. Bernard Morrey, past chair of orthopedic surgery and past member of the board of governors, illustrates the primary principle guiding Mayo Clinic as it invests in its future: Mayo Clinic will succeed best by being Mayo Clinic.

As Dr. Morrey negotiated this change in the clinical practice among his colleagues, there was no compromise of the core value: the needs of the patient come first. In fact, by working together on the problem, they also lived the teamwork value while better meeting the needs of their individual patients because they lowered expense without compromising clinical care. This case study became the model for other Mayo initiatives. According to James R. Francis, chair of supply chain management for Mayo Clinic, a similar project in the pharmacies has saved more than $40 million during the past five years. Other projects—all physician-led—have produced efficiencies in cardiovascular medicine, gastroenterology, radiology, and capital equipment.

The discipline that Mayo exhibits in these supply-chain examples reveals an organization fueled by the internal power of teamwork and focused simultaneously on the customer’s needs and on the financial outcomes required to sustain Mayo Clinic for future generations of patients. As discussed later in the chapter, this organizational discipline and power is now implementing evidence-basedquality measures across the organization. In service organizations, “Control of destiny is a success sustainer…. The senior leaders of the business determine its course—not competitors, not lenders, not institutional shareholders, not unions, not suppliers, not community activists, not the media, not politicians. The senior leaders keep the organization focused on creating superior value for customers, and this focus helps secure the organization’s future.”1

In this chapter, we explore Mayo Clinic’s commitment to tomorrow as seen through the strategic priorities it pursues today: integration of the three campuses into a single, smoothly functioning organization is our first topic. Following are improved quality and safety in the clinical practice, high-value care based on clinical outcomes over time, innovation in healthcare delivery, advocacy on behalf of patient-first interests in healthcare practice and policy reform, and leadership development.

Realizing the Power of One

Dr. Denis Cortese, CEO of Mayo Clinic, is clear: “Mayo Clinic’s purpose in life is caring for patients. We have a hundred years of practice at building a delivery system centered on the individual patient.” Mayo knows where it comes from and where it wants to go, but Mayo Clinic’s destiny is being forged in perhaps the most complex scientific, social, and political environment in its history. The United States is engaged in a national conversation about a healthcare delivery system that most analysts agree is broken; cynics even ask, “What system?” Also looming are questions about how to finance the healthcare that Americans have come to expect. As the entire industry deals with the social and political demand for change, Dr. Cortese sees a national movement toward the vision Mayo has developed: “A healthcare system delivering care focused on the individual patient while providing high value, better outcomes, better safety, better service, and lower cost by integrating and coordinating care among different providers and organizations.” He asserts, “Mayo Clinic is better prepared to live through this than any other large institution.” But Mayo Clinic is not perfect. Its leadership is working to ensure that the organization lives up to its reputation— that it consistently delivers the implicit promise of the brand that brings comfort and peace of mind to those who think of Mayo Clinic when grave illness strikes.

The first order of business under Dr. Cortese’s leadership as president and CEO has been the integration of the three campuses into a single organization. As discussed in Chapter 8, when the Florida and Arizona campuses were opened, it was unclear whether they needed to function as part of a single organization. Some of Mayo’s leaders thought that the parent organization, known as Mayo Foundation at the time, should serve as a holding company with various business units operating with some significant autonomy. When the decisions to expand were made in 1983, Mayo’s leadership was responsible only for Mayo Clinic in Rochester—an outpatient clinic with fewer than 8,000 employees. Many of the organization’s leaders believed that Mayo Clinic was about to reach the maximum size that could be managed effectively. Furthermore, in 1983 the Mayo Clinic operation in Rochester was poised to assume responsibility in 1986 for two local hospitals—Saint Marys and Methodist—which would more than double the number of employees and add untold complexity to the Rochester operation. Given this challenge, Mayo’s leaders were reluctant to become deeply involved in two fledging campuses. It also seemed reasonable to allow the new campuses to have some distance from Rochester’s culture and practices because they were operating in new, unfamiliar regional markets.

However, by 2003 when Dr. Cortese became CEO, it was clear that integration into a single Mayo Clinic organization was necessary. Dr. Dawn Milliner is chair of the clinical practice advisory group. This group consists of leaders from the clinical practice committees on each of the three campuses and is charged with increasing coordination of Mayo’s entire clinical practice. As chair of the clinical practice advisory group, Dr. Milliner has been at the center of the campus integration project. “When we started, people didn’t know each other or where expertise even resided, because we had grown so rapidly and were so separated by geography.” Since the late 1960s Mayo has had a powerful priority paging system that connects two consultants by phone in seconds. It was extended to Jacksonville and Scottsdale in the 1980s. It is a vital communications tool, particularly within the staff on each campus. This technology, however, could not solve the underlying problem: consultants who did not know one another. Videoconferencing also has been available since the practices started in Florida and Arizona. Videoconferencing is helpful, but it also works best after some face-to-face familiarity is established. Shirley Weis, chief administrative officer, indicates that Mayo now realizes the importance of establishing more personal familiarity across the campuses to facilitate integration. This means more travel than in the past.

Dr. Milliner sees the integration initiative as a chance to recapture what the Mayo brothers accomplished in their day—bringing every resource they could to each individual patient. “However, today,” she says, “we have a wonderful opportunity to bring the best of Mayo Clinic care to each patient, no matter where in our system the expertise resides or where the patient is receiving care. We are in a digital age where communication tools permit integration within a much larger organization.” The use of the electronic medical record or a digital CT scan combined with a phone call or an e-mail, for instance, permits real-time consultation with the most qualified expert among all 2,500 Mayo Clinic physicians without regard to geographic location. As we will see later in the chapter, the enterprise learning system has powerful potential to provide automated just-in time patient management information to any Mayo physician whose patient has a rare clinical finding. Dr. Milliner concludes, “It is a daunting task and won’t be easily accomplished. But for me the exciting part is that we are going back to what we inadvertently lost—the ability to leverage our entire system to address each patient’s needs.”

Because integration is a work in progress, its full implications are, as yet, undetermined. But even now, the organization can understand some of what integration means to the Mayo organization. Most importantly, it means that patients will receive the same high-quality service, diagnosis, and treatment regardless of which campuses they use. It means that any physician hired to work on a Mayo Clinic campus is qualified to work on the other two, and today, in contrast to the past, hires are frequently vetted by clinical peers across more than one campus. It means that ultimately there may be one appointment office where now there are three. Integration is leading to common information management systems instead of each campus selecting its own software infrastructure. And very importantly, capital investments and growth decisions will reflect judgments about what is best for Mayo Clinic overall rather than the interests of a single campus. Dr. Cortese speaks of today’s Mayo Clinic as “an organism—a single entity—so if any part of it is not doing well, the whole organism is affected.”

Quality—“We Can Do Better”

Mayo Clinic seeks to control its destiny by accelerating its efforts and investments to improve quality. Dr. Cortese explains that quality—defined by clinical outcomes, safety, and service—at Mayo is excellent, but he believes that the organization can do better. Dr. Stephen Swensen, professor of radiology and Mayo Clinic director for quality, notes, “Mayo Clinic leads all other U.S. providers when you look at objective measures of outcomes, safety, service, preventable death, mortality rates adjusted to account for preexisting medical problems and health status, and adverse events with harm to the patient. For instance, when the hospital standardized mortality rates were first released a couple years ago, Saint Marys Hospital had the lowest mortality rate of any general hospital in the United States and the United Kingdom. When you look at all these measures as a composite, Mayo is at the top.” But, he warns, “We are just at the top of the group of elite providers; we are not as far ahead as we aspire to be.” The caution that Dr. Swensen articulates has become a rallying call from leadership throughout the organization. Dr. Swensen is confident that Mayo will rise to the challenge, “No one is better positioned to break away from the rest of the leaders in clinical reliability than an integrated group practice that values teamwork, understands the dividends of a more horizontal, cross-functional team of nurses, technicians, doctors, pharmacists, and administrators, and has a century-long history of patient-centered care facilitated by a large contingent of systems engineers.” It is clear from interviews with Mayo leaders that they expect improvement.

Mayo Clinic is not isolated from the rest of U.S. healthcare. Although more than 60 percent of Mayo’s physicians have had some training at Mayo Clinic, few have trained there exclusively. Dr. Milliner explains, “Those of us in American medicine accepted error and poor outcomes as inevitable. We told ourselves, ‘That’s just the way it is when you treat complex conditions—there will be some number of adverse effects—we can’t help it.’ Still everyone working from this mindset was trying to get better, while they tolerated some bad outcomes.” Dr. Milliner also suggests that between the 1960s and the end of the 1980s, U.S. medicine experienced tremendous technological advances. “Everyone was focused on new treatments and procedural interventions—using those to improve outcomes. They were not paying much attention to errors in judgment, handoff problems, and safety issues.” In 2000, the Institute of Medicine startled Americans by asserting that as many as 98,000 patients died needlessly each year in U.S. hospitals.2 Mayo Clinic, with the rest of U.S. healthcare, took notice. “We need to take a critical look at ourselves,” Dr. Milliner suggests. “Mayo has been at the front of the curve from the start, but the whole curve is shifting. Even though we do well today, it is not good enough. We know now that it is not the best we can do.”

The rallying call for improving quality is seen, in a sense, as a corrective action. In the early days of Mayo Clinic, the physicians practiced with clear standard procedures. Dr. Swensen notes, “The archives in radiology show, for instance, that a barium exam had an absolute template procedure down to how the tech handed the cup to the patient. We drifted away from that standard work to a more autonomous model where we let physicians come here and practice the way they wanted. So we developed a more heterogeneous practice, which is not a hallmark of high reliability and the ultimate safety environment.” Because Mayo Clinic has hired superb physicians and support staff, its outcomes are still excellent. However, the increased availability of publicly reported data revealed that Mayo has only a narrow lead in positive outcomes generally and that it lags behind other elite providers in some specific cases. “We have a tinge of complacency where we assumed that we were always giving the best care and that our outcomes were always world class—without an opportunity to get much better,” Dr. Swensen adds.

The catalyst to change in this broad initiative is transparency— open sharing of the performance measures of the clinical groups both inside and outside of Mayo Clinic. According to Dr. Cortese, “Transparency means measuring our performance, sharing what we learn broadly, working together to find ways to improve, and reporting our outcomes so that we’re honest with ourselves and others about whether we’re meeting our goals. Mistakes can be a great catalyst for change. Learning from our mistakes is the only way to prevent them from happening again.” Dr. Swensen concurs, “The more we share with one another about our performance—how often diabetics get the best care or when the wrong dose of a medicine is given to a patient or when the right dose goes to the wrong patient— the more we have a catalyst for change, for being the best we can be,” Dr. Swensen says. Mayo Clinic started posting performance outcomes by each practice site on its intranet in October 2007. These outcomes were placed on Mayo Clinic’s Internet site www.MayoClinic.org in December 2007 for public viewing.

Complementing the quality improvement journey are two additional strategic priorities: individualized medicine and the science of healthcare delivery. Individualized medicine stems from recent developments in genomics, “the study of all the genes in a person, as well as interactions of those genes with each other and with that person’s environment.”3 This science opens a new era in which the tools of genomics will likely predict disease and in many cases point to the optimal preventive strategies or treatments. For instance, a patient with genes associated with early onset of colon cancer might be screened with a colonoscopy beginning at age 30 rather than age 50 as recommended for the general population. With early identification and removal of precancerous polyps, colon cancer can be prevented. Individualized medicine may also be applied in cancer treatment where the chemotherapy agent selected for a patient could be determined in some cases by his or her genes.

With a tragic story, Dr. Swensen illustrates the power and vital importance of harnessing the power of genomics and the science of healthcare delivery so as to increase the quality of outcomes, safety, and service. In the recent past, a young Mayo Clinic patient died unnecessarily. “It was a preventable death,” Dr. Swensen says, “The death happened because ‘Mayo didn’t know what Mayo knows.’” The patient was experiencing cardiac symptoms, and the electrocardiogram (ECG) showed a rare “long QT interval,” which is a disorder of the heart’s electrical system. The patient was scheduled for a follow-up appointment in cardiology but died a week before the appointment date.

Dr. Michael Ackerman, a pediatric cardiologist at Mayo Clinic, is the world’s leading authority on long QT interval. He sequenced the gene for an ion channel (a potassium channel in the heart). Out of the three billion nucleotides in the human genome, he determined that when a particular nucleotide is wrong, the patient can suffer a fatal cardiac arrhythmia. The long QT interval on an ECG is clinical evidence often associated with the rare genetic syndrome that leads to the sudden death of a number of children and young adults each year. The lifesaving treatment is the implantation of a defibrillator that is activated when it detects the fatal arrhythmia. Dr. Ackerman’s treatment standards also identify medications that should and should not be used in the presence of this syndrome. But not all caregivers at Mayo Clinic know what Dr. Ackerman knows. Disseminating his knowledge throughout the institution called for a new capability in the science of healthcare delivery.

The parents of a deceased patient made a large donation to Mayo Clinic for the express purpose of improving the reliability of care at Mayo. The initial project creates an electronic means of moving Dr. Ackerman’s knowledge to any Mayo Clinic physician at the moment he or she needs it, whether or not the doctor knows the information is needed. Specifically, Mayo Clinic’s systems engineers built a link between the computer that analyzes the ECG and the mind of the patient’s ordering physician. Today, when the ECG computer identifies the long QT interval and it is verified by a cardiologist, the ECG computer routes the information into the outpatient’s electronic medical record and also routes an automated message to the physician who ordered the ECG. The system has a feedback loop to confirm that the physician received the message. The automated message has a link to Mayo’s enterprise learning system (ELS) which first provides a directory of Mayo Clinic experts on the disease or condition, and then offers answers to frequently asked questions, key facts, and clinical guidelines. The electronic systems provide specialized knowledge to the managing physicians so that they can know what they don’t know about safe care for their patient. This innovation in the science of healthcare delivery helps ensure that patients always get the best care regardless of whom they see or where they are seen in the system.

The ELS represents a large and essential investment in the science of healthcare delivery. Dr. Farrell Lloyd, director of the Education Technology Center, emphasizes that it is impossible for doctors to stay current on all the medical literature produced today as more than 500,000 new reports are added each year to Medline, an online database of published medical research, a service of the U.S. National Library of Medicine. In testimony before Congress, the director of the Library of Medicine described a conscientious physician who faithfully reads two articles each day for a year, and, “By the end of such a year, this good doctor will have fallen 648 years behind on reading the new publications.”4 Moving knowledge from research to patient care is slow and difficult; one study determined that it takes 17 years to translate 14 percent of original research to the benefit of patient care.5 Today, medical education is moving from an emphasis on memorization to the skills of locating and using critical information at the point-of-need in the day-by-day practice of medicine. “The enterprise learning system,” says Dr. Lloyd, “is Mayo Clinic’s way of making the needed information accessible to the physicians as quickly and simply as possible.”

Dr. Swensen admits, “A standard treatment protocol is an incendiary concept for many doctors—they call it ‘cookbook medicine’— because it means they have to perform like the physician next to them and their colleagues on other campuses. But the Mayo Clinic model of care is patient-centered—what would the patient want? Patients come to get Mayo Clinic world-class care. They should get it no matter what door they open. Our quality initiative takes the model of care off the wall and makes it part of how we perform reliable care.”

Others echo Dr. Swensen’s message. James G. Anderson, chief administrative officer in Arizona whose career spans nearly 40 years in healthcare administration inside and outside Mayo, is adamant, “The model that we know as the Mayo Clinic—the integrated practice, shared physician/administrator management, salaried physicians, practice emphasis complemented by research and education—is a powerful and differentiated model in the marketplace. If we are not satisfied with our results, the problem is in our execution, not who we are or our strategic approach to the market.” Mayo Clinic at its best—a team focused on a challenge, responsible for change with resources at hand—is a powerful force. Dr. Swensen describes how Mayo Clinic becomes Mayo Clinic at its best through its approach to quality improvement:

We identify a physician leader who owns the responsibility and assign key team members including a systems engineer who has no other responsibility for the 100-day duration of the project, an administrative project manager, and a data specialist. In addition, a cross-functional team is assembled—physician experts in the disease, nurses, technologists, pharmacists, technicians—with members from across the campuses of the Mayo system. The team is keyed up with a charter so we will know what we are going to measure. And then there is a control phase afterwards. Basically there are 100 days of intense focus on an opportunity for improvement. So with pneumonia in the hospital our team was to identify the best practice. Then they deployed that and measured it. Did it make a difference? We decreased the length of stay, lowered the readmission rate, and demonstrated a lower disease-specific mortality rate for patients with pneumonia who got optimal treatment. We started from a baseline where we had excellent performance, but we thought there was opportunity to get even better. We did that.

Mayo Clinic today holds this belief: the highest quality outcomes, a reliably safe environment, and stellar service come when colleagues work together to determine what is the best care for the individual patient and then execute this care model and patient experience consistently in every clinic and hospital at Mayo Clinic. In other words, every door—including virtual doors—provides the same experience. “Then from that standard of excellence we can innovate because we have something to compare it to,” Dr. Swensen concludes. “Our approach to quality has to be scientific, evidence-based. We need control charts and biostatisticians. This is the science of healthcare delivery.”

Prudent, High-Value Care

As one Mayo leader shared, “We are doing quality for the right reason—to improve the outcomes and safety and reliability of our care. No question that this is the right reason.” There is, of course, a business case as well for driving out needless variation, waste, and defects from the care of patients. Most organizations outside of healthcare do this to improve the bottom line. But for Mayo Clinic, the primary business case is not the net revenue published in the annual report. Rather it is in the affirmation of the fiscal efficiency of Mayo Clinic’s integrated care model. Mayo Clinic must be able to tell its patients and their insurance companies or employers that this high-quality care is not a luxury but a prudent, high-value purchase.

Healthcare is the largest business sector in the United States, and it underperforms all others in terms of efficiency and defect rates. It is frequently not a high-value purchase. A recent study in the New England Journal of Medicine shows that about one-half of the care delivered by physicians in the United States is not based on current best practices.6 As we discuss in Chapter 4, Mayo gets high marks from patients for its efficient use of their time, but some insurers and patients are not quite as sure that Mayo’s care is an efficient use of their money. Mayo Clinic bills can be large in part because all services from physicians, all laboratory tests, and all hospital charges are bundled into a single bill. Integrated bills for care are not the norm in healthcare because services are frequently obtained from several different organizations.

Robert Smoldt, recently retired chief administrative officer of Mayo Clinic, and Dr. Denis Cortese, president and CEO, have led internal efforts to ensure that Mayo’s care is high-value care. They advocate that value is the best metric to identify high-quality, cost-effective medical care among all providers across the nation. In a recent article, they offer a value equation dividing quality (outcomes of care, safety, service) by the cost per patient over time.7 Dr. Cortese observes, “While our charges may be near the top for individual line items on a bill, we don’t do things as often as most others, so the cost over time is favorable.” He also notes that every Mayo Clinic doctor has access to all the laboratory studies, radiology reports, and notes from the other doctors, and this provides fiscal efficiency as well— no need for duplication. Furthermore, if Mayo can prevent a patient from developing a disease such as type-2 diabetes, then the value over time is very high. Diabetes is expensive to manage as a chronic disease for the balance of a lifetime and, if poorly managed, multiple complications create even greater expenses and a compromised quality of life for the patients. Dr. Cortese adds, “By predicting the potential for disease, preventing it when possible, accurately diagnosing disease when it occurs, and then specifically treating, for instance, the type of breast cancer or diabetes, we will over time provide high-quality, high-value care.”

Dr. Dawn Milliner, who led a task force that studied the value equation, takes a big-picture view on the cost issue: “All of us delivering healthcare in the United States need to step back and ask ourselves, ‘What is it about our national system that creates these high costs and poor outcomes.’ Mayo cannot be a responsible provider of healthcare if we don’t look critically at this issue. Mayo Clinic needsto do its part in helping lead the effort to provide better value in healthcare. It is a responsibility to our patients as it is in their best interests—it absolutely squares with our primary value.” Many purchasers of healthcare services—the federal government, major employers, and health plans—have themselves stepped forward with incentives for providers to improve. Under the general rubric of “pay for performance,” these payers have been using money—slightly higher reimbursement levels—in an effort to ensure that their beneficiaries get quality care. However, Smoldt and Dr. Cortese argue that these programs pay for processes, not specifically for outcomes. Further, several of the programs increase payment on a percentage basis, so the inefficient providers whose cost of care is high earn higher dollar rewards than do the efficient providers.

“We have quite a bit of evidence to show that Mayo Clinic’s care model does produce high-value care,” says Smoldt. He points to The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care as the best source of data.8 The Dartmouth researchers contend that the data on healthcare costs in the last six months and the last two years of life are a good measure of efficiency. These costs are high since about a third of all Medicare expenditures for individual patients is made in the last two years of a person’s life. Using the massive data sets for all U.S. Medicare patients, the Dartmouth researchers argue that more care is not necessarily better care: “The extra spending, resources, physician visits, hospitalizations, and diagnostic tests provided in high spending states, regions and hospitals doesn’t [sic] buy longer life or better quality of life….The problem is waste, and overuse … not underuse and healthcare rationing.”9 In discussing academic medical centers, the Dartmouth researchers note that, in their last six months of life, patients using one university hospital in New York City “had 76 physician visits per person; Mayo Clinic patients had only 24 visits.” In the last two years of life, patients at one California university hospital used “twice as much physician labor—measured as full-time equivalent physicians—as does the Mayo Clinic.”10 Although the report does not rank Mayo Clinic as the most efficient provider on every measure in the academic medical center peer group, Mayo is consistently among the most efficient. The authors conclude that most patients near the end of life have no one in charge of their care. However, “Large group practices like Mayo Clinic and integrated delivery systems like Intermountain Healthcare provide examples of how it can be done.”11

In the end, by making the case for recognizing and rewarding high-value providers, Mayo Clinic is advocating for patients. They get higher-quality clinical outcomes, safer treatment, and better service. Making the case for an evidence-based value score will, in the view of Mayo’s leaders, provide two paybacks. First, it will encourage the U.S. healthcare establishment, including doctors, hospitals, payers, and health policy makers, to consider both quality and cost over timein the payment systems of the future. Second, it will position Mayo Clinic as a prudent, high-value purchase.

Delivering Health

Dr. Nicholas LaRusso wants Mayo Clinic to become a leader in the coming transformation of healthcare delivery. An imperative for change seems to be forming around forces that promise to disrupt healthcare business as usual—genomics, communications technologies, a broken and expensive healthcare system, and a maturing Facebook generation that is already breaking many conventional rules. As the founding director of Mayo Clinic’s Center of Innovation and Healthcare Transformation, Dr. LaRusso is focused on things new. He is particularly interested in healthcare delivery that emphasizes maintaining health rather than treating illness. This may well be the dividing line between the medicine of today and the medicine of tomorrow.

In the early 1980s, the Clinic’s leaders were deeply concerned that patients could not or would not continue traveling to Rochester, Minnesota, for care. Today’s leaders have a similar, nagging fear that centers on a potentially more radical revolution of healthcare delivery that would render some types of on-site care obsolete. Communication technologies could—and likely will—replace some, if not much, of the current face-to-face consultation between patients and their physicians. Dr. LaRusso, who is also a past chair of the department of internal medicine in Rochester, sees a distinct possibility that the “annual exam” as now traditionally performed with a standard medical history and a head-to-toes physical exam may become obsolete. A health risk assessment coupled with genetic analysis of the patient may eventually predict disease much more efficiently than a traditional general exam could ever detect it. “Personalized genomic medicine, coupled with evolving imaging techniques, may very well become a disruptive force that will revolutionize the practice of medicine,” states Dr. LaRusso. “While Mayo Clinic will participate in the discovery revolution, it should lead the deliveryrevolution—we need to create a system of delivery that can rapidly introduce these and other innovations as they become available.”

Dr. Glenn Forbes, CEO of Mayo Clinic Rochester, suggests, “With knowledge of the individual’s genetic makeup, people and the medical community will, in the future, shift more focus on the predictive and preventive part of the healthcare curve.” He sees the role of the Center of Innovation and Healthcare Transformation as developing innovations required for bidirectional, interactive wellness relationships. Dr. Forbes illustrates:

Sometime in the future, I could be living any where on the planet, or I could be traveling. I have some type of communication with Mayo because I’m partnering with Mayo in my wellness. It may be a computer chip embedded in a card, or it may be a computer chip embedded in me. Mayo knows my genetic makeup and has cross-referenced my genetic profile with millions of aberrations and cohorts that are similar to my situation to identify several predictive and preventive issues to address. Mayo knows my vulnerabilities, risks, my strengths—that is part of the database.

I feel fine, but I check in every once in a while. If I have a chip embedded, I might even be unknowingly “checking in.” Every seven days, Mayo checks my blood sugar and could send me a message about needing to cut back on the cookies because my sugar level went up from 116 to 124. This information and advice is part of my partnership— part of what I have decided to purchase for my personal benefit.

But now, I’m traveling in France and I feel ill and need some interaction with Mayo. To stimulate my chip—if on a plastic card— I stick it into the Health Maintenance “ATM” in the hotel, and the ATM recognizes me—just like a bank today recognizes me when I use my bank card on the streets of Paris. I tell Mayo what is going on—I’ve been having headaches. Mayo responds, “Your genetics suggest that you are prone to headaches if you’ve been eating too much pasta. But, if you want to see a doctor, we have a Mayo Clinic alumnus or affiliated provider located, according to your GPS information, just two miles away. Here are the coordinates for the office, and we’ve already alerted the office that you will probably be coming.”

Here, I have a partnership with Mayo, and I’m using whatever communications technology is available at the time to give intelligent consultations and interactions as I live my life in wellness.

Physicians in this new era will still analyze clinical data and convey its meaning to patients; the conversations will still require listening skills and sensitivity to the uniqueness of individuals. New, however, will be the conversation about the meaning of the risks identified in a patient’s genetic profile. Dr. LaRusso illustrates, “We already have two genetic patterns that predict one’s chances of getting breast cancer—breast cancer gene mutation 1 (BRCA1) and BRCA2. But these together account for only a small percentage of all breast cancer. When we get BRCA3, 4, 5, 6, 7, … 10, tests which are on the horizon, we may identify genetic patterns for early disease onset where the individual should start getting mammograms or another special diagnostic test at age 20. Other patterns might suggest an optimal window in which the woman should have children.” Likewise, some patients may have genetic patterns associated with cancer onset after menopause, so mammograms could safely wait years beyond today’s recommendations.

Much of this testing and information exchange does not require that the patient be present in front of a Mayo Clinic doctor. Increasingly, such care could be delivered to patients anywhere in the world through new communications technology. “This could lead to a new concept of Mayo Clinic as a destination medical center—a URL,” observes Dr. LaRusso. “An appointment with Mayo would not always require you to leave your home.” In fact, Mayo, in partnership with Blue Cross Blue Shield of Minnesota, is already conducting a feasibility project between clinics in the Duluth, Minnesota, area and Mayo Clinic Rochester. If the patient and the primary care doctor in Duluth feel a referral to Rochester is in order, they can opt for a “virtual consultation” where a doctor in Rochester reviews the provided information from a secure Web portal and shares an opinion electronically within 48 hours. Business models for this type of service are already being tested. “We’ve learned from our proof of concept testing so far that most patients and their primary care doctors can be served in this virtual model and that the patient will not need to travel to Rochester,” says Barbara Spurrier, senior administrator for Mayo’s Center of Innovation and Healthcare Transformation. “When it is determined that the patient needs to come to a place like Mayo Clinic for a major surgical or procedural intervention, their care management is expedited because of the virtual consult.”

Mayo Clinic’s reputation for reliability and patient advocacy should position the Clinic favorably in the business of this healthcare information exchange. But before a new idea can become a reality in the marketplace, it must be transformed into a viable customer experience and a solid business proposition. This is where the new Center enters the picture. Barbara Spurrier emphasizes that transforming ideas and innovations requires expertise that does not fully exist inside Mayo Clinic today: “Innovation will be approached as a discipline.”

The innovation center grows from the SPARC (see, plan, act, refine, communicate) project that was based in the department of internal medicine under the leadership of Dr. LaRusso and Spurrier, who was the lead administrator for the department at the time. SPARC has focused on redefining how in-person healthcare is delivered. A large suite of office and examination space in Mayo’s outpatient facility in Rochester was converted into a care delivery laboratory. The facility features movable walls, for instance, that can be reconfigured to test the functionality of space. After a care delivery prototype is created, it is studied in real time as it serves as an outpatient clinic used by doctors and patients for actual appointments. More than 25 major explorations in care delivery have been conducted in SPARC.

Both Dr. LaRusso and Dr. Forbes emphasize that the transformation envisioned will not make bricks and mortar institutions obsolete. The relationships formed in wellness healthcare would convert to illness healthcare if necessary and, perhaps, even on a Mayo Clinic campus. “Patients will still need hands-on, in-person medical care for procedures and surgeries. Patients will also require access to sophisticated diagnostic and treatment equipment,” says Dr. Forbes. “We intend to maintain Mayo Clinic as an attractive destination—both in the virtual sense and in the sense of a physical location.”

Speaking Out

In 2006, the Mayo Clinic Health Policy Center officially entered the high-level public conversation on healthcare reform. “Our public trustees asked Mayo Clinic’s leadership to invest some of Mayo’s reputation for patient advocacy in the dialogue and debate on reform of the U.S. healthcare system,” says Robert Smoldt who became the founding director of the Health Policy Center in 2005 while still serving as Mayo Clinic’s chief administrative officer. Looking back at the proposals of the 1980s and even the efforts of President Bill Clinton’s administration beginning in 1993, it is clear that the voice of the patient doomed what policymakers thought were good ideas. Patients wanted choice, and they wanted care from doctors and hospitals that were motivated by the patient’s clinical best interests. “The long success of Mayo Clinic, our high patient satisfaction, and the early evidence of Mayo Clinic as a high-value provider create much of the credibility for our voice in the discussions,” says Smoldt.

Three tenets underscore Mayo Clinic’s position on health reform: First, everyone in the United States needs health insurance. Second, everyone needs access to integrated care. This idea suggests that community medicine everywhere should reflect key elements, such as common medical records, doctors working collaboratively and seamlessly between clinical specialties, and doctors and hospitals functioning smoothly together in the best interests of patients. Third, all healthcare provided should be evaluated by a value metric that considers medical outcomes as well as cost over time. These positions have been formulated from patients, patient advocacy groups, and leading healthcare thinkers who have attended Mayo-sponsored symposia and working sessions around the country since 2006.

In an interview conducted for this book, Smoldt paused, and then told this story:

In the 1970s, early in my career at Mayo Clinic, I had a chance to work for Dr. Jack Hodgson, who was the chair of radiology and on the board of governors. He just loved Mayo Clinic like a lot of us do. Outside of his work at Mayo, he was a visible and outspoken pacifist. After I’d gotten to know him for a year or so, he asked, “What do you think of Mayo Clinic?” I didn’t have a quick response, so he continued, “You know, I’m a pacifist, but I think that I’d kill for Mayo Clinic.”

Smoldt then acknowledges that, like Dr. Hodgson, he is of two minds. The first is an altruistic emphasis on a healthcare policy that focuses on the needs of patients. The second is his personal desire that organizations like Mayo Clinic be protected and preserved for future generations of patients. Smoldt’s second concern is not just his own; it is shared by Mayo’s trustees and leaders as well as by patients. Healthcare is not fully controlled by market forces. Medicare and Medicaid patients make up 30 to 60 percent of the patients treated on the individual campuses of Mayo Clinic. Those patients do not pay “market rates” for their services because price caps have been imposed by public policy. Healthcare providers work in a market where public policy, political philosophies, and political “horse trading” can have rich or devastating impacts. Smoldt continues:

We in the Health Policy Center believe that sometime in the next decade the United States will either undertake major healthcare reform or will have to reform the Medicare program. The huge inflow of baby boomers into an environment where medicine can do more and more for patients makes Medicare as it exists today unsustainable. Something has to happen. Some ask, “Do you think how Medicare gets reformed will have much of an impact on Mayo Clinic?” I think it will be huge. It is in Mayo Clinic’s own self-interest to be very involved in the discussion and seek a result that will enable us to continue our long tradition of patient-centric medical care.

Cultivating Tomorrow’s Leaders

Mayo Clinic’s senior leaders have few worries about the next generation of Clinic leaders, including the physician leaders. In fact, two generations of future leaders are mostly on campus today, and they are being deliberately readied for senior leadership positions. The talent pool includes many from which a smaller number will become candidates for major positions as they open over time. This speaks to two important commitments: First, Mayo’s commitment to find internal talent to sustain the values, culture, and clinical model that have proven to be effective for so long. Never has the chief executive officer come from outside of Mayo, and in only a few cases has an individual been hired from outside Mayo to fill a senior administrative leadership position. Second, Mayo has a commitment to deliberately cultivate physician and high-level administrative leaders. The talent pool seems deeper than in the past, thanks in part to the Mayo Clinic career and leadership development program.

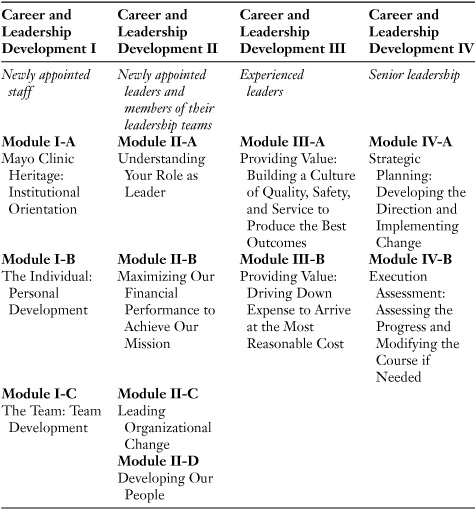

The current program is a successor to training courses conducted on campus beginning in the mid-1990s. In 2005, the new program began to take shape with the realization that Mayo’s general introduction to management skills and fundamental content from short courses in finance, marketing, and management were not sufficient for the physician/scientist leaders needed in the twenty-first century. “Also most external programs were not specific enough to address Mayo’s needs,” states Dr. Teresa Rummans, chair of the career and leadership development program at Mayo Clinic and a member of the executive board in Rochester. “This program does address the unique needs of Mayo and its future leaders in an economically feasible way.” The facilitators and presenters are predominantly internal, but external experts from academia lead topics such as individual development and change management.

“This program strives to create leaders who can lead comprehensive changes in care management,” wrote its designers.12 Change in healthcare is difficult because leaders lead peers, not underlings. Physician leaders must persuade and inspire physicians to change. “We try to explain to those in the course how one can drive change in Mayo Clinic with its various committees and its commitment to consensus management,” says Dr. Robert Nesse, currently the CEO of Franciscan Skemp, a Mayo Health System organization in La Crosse, Wisconsin, and a member of the board of governors. Dr. Nesse was selected as a presenter in the course based on his deep leadership experience in Rochester before going to La Crosse; he speaks with an authority about Mayo Clinic’s management culture as no one from outside Mayo could.

The program (outlined in Table 9-1) begins with three modules (identified in the left column) that all new physicians go through. These three modules are spread over a week. The level II program, taught over three and one-half days, is required of all new chairs and their leadership team members. Both physicians and administrators participate in this program. In level III, selected department chairs and other leaders—sometimes as many as 250 individuals—participate

Table 9-1

Mayo Clinic’s Career and Leadership Program

in the one and one-half day program. Finally, level IV serves the combined executive boards of the three campuses as well as the board of governors. “One special feature of this program is that it is justin-time education. The courses are offered just before or after the participants first need the information,” explains Dr. Rummans.

Dr. Nesse observes that another objective of the program is to create “a community of leaders” among the newly appointed young leaders who may interact with one another over the next decade or two. By thinking of themselves as leaders rather than as just ophthalmologists, or pathologists, or rheumatologists, they can identify with a new role in their career of Mayo Clinic leadership.

Lessons for Managers

Great leaders create the future of their organizations. That is a tall order for any company in the twenty-first century and quite challenging in healthcare. Healthcare delivery of tomorrow is being shaped today by forces that a healthcare provider, even a very large provider like Mayo Clinic, can influence but not control. Around the world, laboratories in universities and corporations are developing new science and technology. In executive conference rooms and legislative halls, committed minds are grappling with healthcare policy, costs, and controls. Society wrestles with issues of equity and rights that determine who has access to the best that healthcare can offer. Physicians try to make the delivery system work for patients even as they often struggle with conflicting interests within this system that includes hospitals, insurers, employers, and pharmaceutical companies in addition to themselves. Yet, as one participant in this complex web of interests and players, Mayo Clinic strives to control its own destiny by being true to its core values and strategies while investing to ensure its strategic relevance and quality leadership tomorrow. Managers can learn from this organization where power is distributed widely and leaders can lead but not control.

Lesson 1: Excellence is a journey. Excellence is a journey and perfection—zero defects—is the elusive destination. The first great leap in excellence at Mayo Clinic came when the Mayo brothers decided to wash their hands between surgical cases—an idea they got from others. Though their father first scoffed at the idea, the low mortality in their subsequent work convinced him and also earned their clinic its initial reputation for excellence. The battle against hospital-acquired infections, a century later, still has not been won, and the hand-washing journey at Mayo and other healthcare institutions continues.

Every organization that strives for excellence must define the goal and map the journey. Mayo Clinic is not content to be a leader in a cluster of excellence, so it has embarked on an aggressive effort to widen the distance between its measured quality and the rest of the best. The map reflects the “Mayo way”—a collaborative effort using the best resources available to produce a higher level of quality to serve the best interests of the patient. This is difficult work, and, in part, the employees are powered on this journey by leaders who challenge and inspire—extrinsic fuel.

Mayo Clinic is fortunate because its work force is intrinsically driven. There is no bonus for extra effort, no extra vacation days at Mayo. Mayo endeavors to hire the best—those achievers who earlier were satisfied only when their name was at the top of the grade curve posted after exams. Transparency of the gap between what is and what could be will further energize an organization whose workforce is committed to learning, high achievement, and the best for its customers.

Mayo Clinic, the strongest healthcare brand in the United States, has a sense of urgency about improving the quality of service it delivers and the range of services it offers. That Mayo is an industry leader in various quality metrics takes a back seat to its desire to get better. Having built its stellar reputation by delivering care to the sickest of patients, Mayo is now embarking on extending its care model to help prevent sickness. Excellent organizations such as Mayo Clinic always focus their energies on getting better—the journey—and this is a valuable lesson for all managers.

Lesson 2: Align structure with the brand. The brand must be the same in every venue and offering. Mayo Clinic’s patients expect to find Mayo Clinic behind every door and every portal that bears the name. Although the patient satisfaction studies showed that the patient experience was successfully replicated and the culture of service had been transplanted in the new clinics in Florida and Arizona, something was still not right after 15 years of operation. The collegial teamwork value suffered when sister organizations competed with one another, when physician colleagues over a thousand miles away were strangers, and when leaders grumbled as central resources were allocated. The clinical services Mayo provides are not always completed at the site where they begin; complex patient care is sometimes handed off from one campus to another. So it is not sufficient for each campus to execute the Mayo model of care independently. Patients appropriately expect that the teamwork between campuses be equivalent to the teamwork on one campus.

Controlling the destiny of an organization requires an alignment of forces in services and in management. Though rare, service lapses clarified that the holding company model did not work for the geographic extensions of the Mayo Clinic brand. “One Mayo” became the mantra, and its definition is maturing through personal relationships, clinical collaborations, investment in common systems, more staff movement between campuses, and numerous multicampus experiments. For instance, Dr. Wyatt Decker serves as the chair of the department of emergency medicine in both Rochester and Jacksonville. The department of neurology has a “division” structure in neurology subspecialties such as clinical neurophysiology and behavioral neurology with membership that spans the three campuses to coordinate research and education. Determined senior leaders are investing significant resources toward the journey to “one Mayo.” For an organization that invented the concept of an integrated, multispecialty medical practice, a concerted effort to strengthen geographic teamwork became inevitable once the decision was made to expand geographically. It was a matter of “when” and “how,” not “if.” Culture could take the organization only so far; structure had to do its part, too.

One of the most vexing issues that leaders of all multiunit organizations face is determining and implementing the proper balance between centralization and decentralization. The issue is not, “What is the best structure?” but, rather, “What is the best structure to execute the strategy?” As discussed in Chapter 8, a brand is a promise of performance. It is instructive that Mayo’s leadership is using an internal brand—one Mayo—to help strengthen its external brand.

Lesson 3: Challenge the performers to improve the performance. Few employees, regardless of profession or vocation, who have become proficient in their work take kindly to advice from “management” or outsiders who have never sat in their chair. The teamwork value takes some of the edge away from Mayo doctors as the clinical decision is often a shared rather than a solo performance, and in general, physicians surrender some autonomy to serve at Mayo Clinic. Examples earlier in this chapter show physicians leading successful changes in the clinical practice of their peers; for instance, establishing a higher standard of care in the management of pneumonia and instigating a cost reduction resulting in a positive $8 million savings on the bottom line for the orthopedic practice in Rochester. Here surgeons using evidence-based research both honored Mayo’s underlying values and determined scientifically the changes needed in their own practice. They, not the CEO or the chief financial officer or even the department chair, brought the changes into being.

In preparing for tomorrow today, Mayo is redoubling efforts to improve in every part of the organization (Lesson 1). It is doing so by delegating improvement to the people who know the work best; the performers are being challenged to improve the performance. Teams of employees are being charged with achieving higher standards of quality for the practice. Doctors lead, but representatives from the whole care team—nurses, therapists, technicians, computer programmers, systems engineers—gather to solve the problems. The team members are drawn from the various campuses in the spirit of “one Mayo.” Together these experts design the care protocols and implementation plan and then measure the results. The authority to take an organization to a higher level of performance is in the minds and hands of the subject experts who do the work. Although leaders must articulate the vision, communicate its importance, and provide the resources of time and tools, they become active spectators as the teams transform service delivery.

Summary

A pivotal question for any service provider is, “What is the impact of the Facebook generation on my organization?” Investing in the future requires an answer to this and other questions. Sustaining yet extending an excellent organization to serve a new generation of customers means transformation, but it begins with a clear sense of identity based on commitment to core values. It requires innovation and leaders who can lead change. It depends on performers who are committed to improving the performance. It is a daily challenge, a quest without end centered on serving the needs of tomorrow’s customers.

NOTES

1. Leonard L. Berry, Discovering the Soul of Service: The Nine Drivers of Sustainable Business Success (New York: The Free Press, 1999), p. 111.

2. Committee on Quality Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine, To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2000).

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, available at: www.cdc.gov.

4. Donald A. B. Lindberg, “NIH: Moving Research from the Bench to the Bedside,” statement to U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Energy and Commerce; subcommittee on Health, 108th Congress, 1st Session, July 10, 2003.

5. E. Andrew Balas and Suzanne A. Boren, “Managing Clinical Knowledge for Health Care Improvement,” 2000 Yearbook of Medical Informatics (Bethesda, MD: National Library of Medicine) pp. 65–70.

6. E. A. McGlynn, S. M. Asch, J. Adams, et al., “The Quality of Healthcare Delivered to Adults in the United States,” New England Journal of Medicine, 2003, pp. 2635–2645.

7. Robert K. Smoldt and Denis A. Cortese, “Pay-for-Performance or Pay for Value?” Mayo Clinic Proceedings, February 2007, pp. 210–213.

8. Dartmouth Medical School Center for the Evaluative Clinical Sciences, Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care, available at: www.dartmouthatlas.org.

9. John Wennberg, Elliott Fisher, and Sandra Sharp, “Executive Summary” from The Care of Patients with Severe Chronic Illness: An Online Report on the Medicare Program, (Trustees of Dartmouth College, 2006), p. 1. Available at: http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/atlases/2006_Atlas_Exec_Summary.pdf.

10. Wennberg, Fisher, and Sharp, p. 2.

11. John Wennberg, Elliott Fisher, and Sandra Sharp, The Care of Patients with Severe Chronic Illness: An Online Report on the Medicare Program, (Trustees of Dartmouth College, 2006), p. 71. Available at: http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/atlases/2006_Chronic_Care_Atlas.pdf.

12. Robert Nesse, Teresa Rummans, and Scott Gorman, “The New Physician/Scientist Leaders: Mayo Clinic Responds to Changing Trends in Healthcare Executive Education,” Group Practice Journal, April 2007, pp. 13–17.