In 1992, the airlines lost a combined $2 billion, matching a dismal 1991, and bringing their three-year red ink total to a disastrous $8 billion. Three carriers—TWA, Continental, and America West—were operating under Chapter 11 bankruptcy, and others were lining up to join them. But one airline, Southwest, was profitable as well as rapidly growing—with a 25 percent sales increase in 1992 alone. Interestingly enough, it was a low-price, bare-bones operation, run by a flamboyant CEO, Herb Kelleher. He had found a niche, a strategic window of opportunity, and oh how he milked it! See the following Information Box for further discussion of strategic windows of opportunity and their desirable accompaniment, SWOT analysis.

Herb Kelleher impressed people as an eccentric. He liked to tell stories, often with himself as the butt, and many involved practical jokes. He admitted that he sometimes was a little scatterbrained. In his cluttered office, he displayed a dozen ceramic wild turkeys as a testimonial to his favorite brand of whiskey. He smoked five packs of cigarettes a day. As an example of his zaniness, he painted one of his 737s to look like a killer whale, in celebration of the opening of Sea World in San Antonio. Another time, during a flight he had flight attendants dress up as reindeer and elves, while the pilot sang Christmas carols over the loudspeaker as he gently rocked the plane.

Kelleher is a "real maniac," said Thomas J. Volz, vice-president of marketing at Braniff Airlines. "But who can argue with his success?"[201]

Kelleher grew up in Haddon Heights, New Jersey, the son of a Campbell Soup Company executive. He graduated from Wesleyan University and New York University law school, then moved to San Antonio in 1961, where his father-in-law helped him set up a law firm. In 1968, he and a group of investors put up $560,000 to found Southwest; of this amount, Kelleher contributed $20,000.

In the early years he was the general counsel and a director of the fledgling enterprise. But in 1978 he was named chairman, despite his having no managerial experience, and in 1981 he became CEO. His flamboyance soon made him the most visible aspect of the airline. He starred in most of its TV commercials. A rival airline, America West, charged in ads that Southwest passengers should be embarrassed to fly such a no-frills airline, whereupon Kelleher appeared in a TV spot with a bag over his head. He offered the bag to anyone ashamed to fly Southwest, suggesting it could be used to hold "all the money you'll save flying us."[202]

He knew many of his employees by name, and they called him "Uncle Herb" or "Herbie." He held weekly parties for employees at corporate headquarters. And he encouraged such antics by his flight attendants as organizing trivia contests, delivering instructions in rap, and awarding prizes for the passengers with the largest holes in their socks. But the wackiness had a shrewd purpose: to generate a gung-ho spirit to boost productivity. "Herb's fun is infectious," said Kay Wallace, president of the Flight Attendants Union Local 556. "Everyone enjoys what they're doing and realizes they've got to make an extra effort."[203]

Southwest was conceived in 1967, folklore tells us, on a napkin. Kelleher was still a lawyer, and Rollin King, one of his clients, had an idea for a low-fare, no-frills airline to fly between major Texas cities. He doodled a triangle on the napkin, labeling the points Dallas, Houston, and San Antonio.

The two tried to go ahead with the plan, but were stymied for more than three years by litigation, battling Braniff, Texas International, and Continental over the right to fly. In 1971, Southwest won, and it went public in 1975. At that time, it had four planes flying between the three cities. Lamar Muse was president and CEO from 1971 until he was fired by Southwest's board in 1978. Then the board of directors tapped Kelleher.

At first, Southwest was in the throes of life-and-death low-fare skirmishes with its giant competitors. Kelleher liked to recount how he came home one day "beat, tired, and worn out. So I'm just kind of sagging around the house when my youngest daughter comes up and asks what's wrong. I tell her, 'Well, Ruthie, it's these damned fare wars.' And she cuts me right off and says, 'Oh, Daddy, stop complaining. After all, you started 'em.' "[204]

For most small firms, competing on a price basis with much larger, well-endowed competitors is tantamount to disaster. The small firm simply cannot match the resources and staying power of bigger competitors. Yet Southwest somehow survived. Not only did it initiate the cutthroat price competition, but it achieved cost savings in its operations that the larger airlines could not. The question then became: How long would the big carriers be content to maintain their money-losing operations and match Southwest's low prices? And the big airlines eventually blinked.

In its early years, Southwest faced other legal battles. Take Dallas and Love Field. The original airport, Love Field, is close to downtown Dallas, but it could not geographically expand at the very time when air traffic was increasing mightily. A major new facility, Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport, replaced it in 1974. This boasted state-of-the-art facilities and enough room for foreseeable demand, but it had one major drawback: it was 30 minutes farther from downtown Dallas. Southwest was able to avoid a forced move to the new airport and to continue at Love. But in 1978, competitors pressured Congress to bar flights from Love Field to anywhere outside Texas. Southwest was able to negotiate a compromise, now known as the Wright Amendment, that allowed flights from Love Field to the four states contiguous to Texas. In retrospect, the Wright Amendment forced onto Southwest a key ingredient of its later success: the strategy of short flights.[205]

Southwest grew steadily, but not spectacularly, through the 1970s. It dominated the Texas market by appealing to passengers who valued price and frequent departures. Its one-way fare between Dallas and Houston, for example, was $59 in 1987, versus $79 for unrestricted coach flights on other airlines.

In the 1980s, Southwest's annual passenger traffic count tripled. At the end of 1989, its operating cost per revenue mile—the industry's standard measure of cost-effectiveness—was just under 10 cents, which was about 5 cents per mile below the industry average.[206] Although revenues and profits were rising steadily, especially compared with the other airlines, Kelleher took a conservative approach to expansion, financing it mostly from internal funds rather than taking on debt.

Perhaps the caution stemmed from an ill-fated acquisition in 1986. Kelleher bought a failing long-haul carrier, Muse Air Corp., for $68 million, and renamed it TransStar. (This carrier had been founded by Lamar Muse after he left Southwest.) But by 1987, TransStar was losing $2 million a month, and Kelleher shut down the operation.

By 1993, Southwest had spread to 34 cities in 15 states. It had 141 planes, and each of them made 11 trips a day. It used only fuel-thrifty 737s, and still concentrated on flying large numbers of passengers on high-frequency, one-hour hops at bargain fares (average $58). Southwest shunned the hub-and-spoke systems of its larger rivals and took its passengers direct from city to city, often to smaller satellite airfields rather than congested major metropolitan fields. With rock-bottom prices, and no amenities, it quickly dominated most new markets it entered.

As an example of Southwest's impact on a new market, it came to Cleveland, Ohio, in February 1992, and by the end of the year was offering 11 daily flights. In 1992, Cleveland Hopkins Airport posted record passenger levels, up 9.74 percent from 1991. "A lot of the gain was traffic that Southwest Airlines generated," noted John Osmond, air trade development manager.[207]

In some markets, Southwest found itself growing much faster than projected, as competitors either folded or else abandoned directly competing routes. For example, in Phoenix, America West Airlines cut back service in order to conserve cash after a Chapter 11 bankruptcy filing. Of course, Southwest picked up the slack, as it did in Chicago when Midway Airlines folded in November 1992. And in California, Southwest's arrival led several large competitors to abandon the Los Angeles-San Francisco route, unable to meet Southwest's $59 one-way fare. Before Southwest, fares had been as high as $186 one way.[208]

Cities that Southwest did not serve began petitioning for service. For example, Sacramento, California, sent two county commissioners, the president of the chamber of commerce, and the airport director, to Dallas to petition for service. Kelleher consented a few months later. In 1991, the airline received 51 similar requests.[209]

A unique situation was developing. On many routes, Southwest's fares were so low that they competed with buses, and even with private cars. By 1991, Kelleher did not even see other airlines as his principal competitors: "We're competing with the automobile, not the airlines. We're pricing ourselves against Ford, Chrysler, GM, Toyota, and Nissan. The traffic is already there, but it's on the ground. We take it off the highway and put it on the airplane."[210]

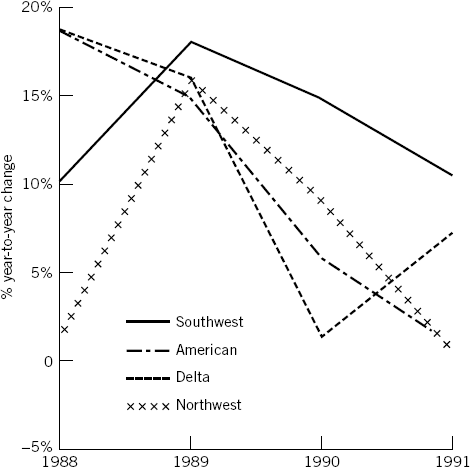

Various aspects of Southwest's growth and increasingly favorable competitive position during the salient years from 1987 to 1991 are depicted in Tables 13.1, 13.2, and 13.3, and Figure 13.1. While Southwest's total revenues were still less than those of the major airlines in the industry, its growth pattern indicated a major presence, and its profitability was second to none.

Southwest's formidable competitive power was perhaps never better epitomized than in its 1990 invasion of populous California. By 1992, it had become the second-largest player, after United, with 23 percent of intrastate traffic. This was achieved by pushing down fares as much as 60 percent on some routes. The big carriers, which had tended to surrender the short-haul niche to Southwest in other markets, suddenly faced a real quandary in the "Golden State." Now Southwest was being described as a "500 pound cockroach, too big to stamp out."[211]

Table 13.1. Growth of Southwest Airlines; Various Operating Statistics, 1982–1991

Operating Revenues ($ millions) | Net Income ($ millions) | Passengers Carried (thousands) | Passenger Load Factor | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Source: Company annual reports. | ||||

Commentary: Note the steady increase in revenues and in number of passengers carried. White the net income and load factor statistics show no appreciable improvement, these statistics still are in the vanguard of an industry that has suffered badly in recent years. See Table 13.2 for a comparison of revenues and income with the major airlines. | ||||

1991 | $1,314 | $26.9 | 22,670 | 61.1% |

1990 | 1,187 | 47.1 | 19,831 | 60.7 |

1989 | 1,015 | 71.6 | 17,958 | 62.7 |

1988 | 860 | 58.0 | 14,877 | 57.7 |

1987 | 778 | 20.2 | 13,503 | 58.4 |

1986 | 769 | 50.0 | 13,638 | 58.8 |

1985 | 680 | 47.3 | 12,651 | 60.4 |

1984 | 535 | 49.7 | 10,698 | 58.5 |

1983 | 448 | 40.9 | 9,511 | 61.6 |

1982 | 331 | 34.0 | 7,966 | 61.6 |

Table 13.2. Comparison of Southwest's Growth in Revenues and Net Income with Major Competitors, 1987–1991

1991 | 1990 | 1989 | 1988 | 1987 | % 5-year Gain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Source: Company annual reports. | ||||||

Commentary: Southwest's revenue gains over these five years outstripped those of its largest competitors. While the percentage gains in profitability are hardly useful because of the erratic nature of airline profits during these years, Southwest stands out starkly as the only airline to be profitable each year. | ||||||

Operating Revenue Comparisons ($ millions) | ||||||

American | $9,309 | $9,203 | $8,670 | $7,548 | $6,369 | 46.0 |

Delta | 8,268 | 7,697 | 7,780 | 6,684 | 5,638 | 46.6 |

United | 7,850 | 7,946 | 7,463 | 7,006 | 6,500 | 20.8 |

Northwest | 4,330 | 4,298 | 3,944 | 3,395 | 3,328 | 30.1 |

Southwest | 1,314 | 1,187 | 1,015 | 860 | 778 | 68.9 |

Net Income Comparisons ($ millions) | ||||||

American | (253) | (40) | 412 | 450 | 225 | |

Delta | (216) | (119) | 467 | 286 | 201 | |

United | (175) | 73 | 246 | 426 | 22 | |

Northwest | 10 | (27) | 116 | 49 | 64 | |

Southwest | 27 | 47 | 72 | 58 | 20 | |

The California market was indeed enticing. Some 8 million passengers each year flew between the five airports in metropolitan Los Angeles and the three in the San Francisco Bay area, this being the busiest corridor in the United States. It was also one of the pricier routes, as the low fares of AirCal and Pacific Southwest Airlines had been eliminated when these two airlines were acquired by American and US Air.

Table 13.3. Market Share Comparison of Southwest with Its Four Major Competitors, 1987–1991

1991 | 1990 | 1989 | 1988 | 1987 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Source: Company annual reports. | |||||

Total Revenues (millions): | |||||

American, Delta, | |||||

United, Northwest | $29,757 | $29,144 | $27,857 | $24,633 | $21,835 |

Southwest Revenues: | 1,314 | 1,187 | 1,015 | 860 | 778 |

Percent of Big Four | 4.4 | 4.1 | 3.6 | 3.5 | 3.6 |

Increase in Southwest's market | share,1987- | −1991: 22% | |||

Figure 13.1. Year-to-year percentage changes in revenues, Southwest and its three major competitors, 1988–1991.

Into this situation Southwest charged, with low fares and frequent flights. While airfares dropped, total air traffic soared 123 percent in the quarter Southwest entered the market. Competitors suffered; American lost nearly $80 million at its San Jose hub, while US Air also lost money even though it cut service drastically. United, the market leader, quit flying the San Diego-Sacramento and Ontario-Oakland routes, where Southwest had rapidly built up service. The quandary of the major airlines was all the greater because this critical market fed traffic into the rest of their systems, especially the lucrative transcontinental and trans-Pacific routes. They could hardly abdicate California to Southwest. American, for one, considered creating its own no-frills shuttle for certain routes. But the question remained: could anyone stop Southwest with its formula of lowest prices and lowest costs and frequent schedules? And, oh yes, good service and fun.

Although Southwest's operation under Kelleher had a number of rather distinctive characteristics contributing to its success pattern and its seizing of a strategic window of opportunity, the key factors appear to have been cost containment, employee commitment, and conservative growth.

Southwest has been the lowest-cost carrier in its markets. While its larger competitors might try to match its cut-rate prices, they could not do so without incurring sizable losses. Nor did they seem able to trim their costs to match Southwest. For example, in the first quarter of 1991, Southwest's operating costs per available seat mile (i.e., the number of seats multiplied by the distance flown) were 15 percent lower than America West's, 29 percent lower than Delta's, 32 percent lower than United's, and 39 percent lower than US Air's.[212]

Many aspects of the operation contributed to these lower costs. Because all its planes were aircraft of a single type, Boeing 737s, the costs of training, maintenance, and inventory could be reduced. And because a plane earns revenues only when flying, Southwest was able to achieve a faster turnaround time on the ground than any other airline. Although competitors take upwards of an hour to load and unload passengers and then clean and service the planes, some 70 percent of Southwest's flights have a turnaround time of 15 minutes, while 10 percent have even pared the turnaround time to 10 minutes.

Southwest also curbed costs in areas of customer service. It offered peanuts and drinks, but no meals. Boarding passes were reusable plastic cards. Boarding time was minimal because there were no assigned seats. Southwest subscribed to no centralized reservation service. It did not even transfer baggage to other carriers; that was the passengers' responsibility. Admittedly, such customer service frugality would be less acceptable on longer flights—and this helped to account for the difficulty competing airlines had in cutting their costs to match Southwest's. Still, if the price is right, many passengers might also opt for no frills on longer flights.

Kelleher was able to achieve an esprit de corps unmatched by other airlines despite the fact that Southwest employees were unionized. His relationship with the unions was not adversarial, so that Southwest was able to negotiate flexible work rules, with flight attendants and even pilots helping with plane cleanup. Employee productivity continued very high, permitting the airline to be lean staffed. Kelleher resisted the inclination to hire extravagantly when times were good, necessitating layoffs in leaner times. This contributed to employee feelings of security and loyalty. The low-key attitude and sense of fun that Kelleher engendered helped, perhaps more than anyone could have foreseen. Kelleher declared, "Fun is a stimulant to people. They enjoy their work more and work more productively."[213]

Not the least of the ingredients of success was Kelleher's conservative approach to growth. He resisted the temptation to expand vigorously—for example, to seek to fly to Europe or get into head-to-head competition with larger airlines with long-distance routes. Even in its geographical expansion, conservatism prevailed. The philosophy of expansion was to do so only when enough resources could be committed to go into a city with 10 to 12 flights a day, rather than just one or two. Kelleher called this "guerrilla warfare," with efforts concentrated against stronger opponents in only a few areas, rather than dissipating strength by trying to compete everywhere.

Even with a conservative approach to expansion, the company showed vigorous but controlled growth. Its debt, at 49 percent of equity, was the lowest among U.S. carriers. Southwest also had the airline industry's highest Standard & Poor's credit rating.

In its May 2, 1994 edition, prestigious Fortune magazine devoted its cover story to Herb Kelleher and Southwest Airlines. It raised an intriguing question: "Is Herb Kelleher America's Best CEO?" It called him a "people-wise manager who wins where others can't."[214] Southwest's operational effectiveness continued to surpass all rivals in such productivity ratios as cost per available seat mile, passengers per employee, and employees per aircraft. Only Southwest remained consistently profitable among the big airlines, by the end of 1998 having been profitable for 26 consecutive years. Operating revenue had grown to $4.2 billion (it was $1.3 billion in 1991—see Table 13.2), and net income was $433 million, up from $27 million in 1991.

In 1999, Herb Kelleher was named CEO of the Year by Chief Executive magazine.

Late in October 1996, Southwest launched a carefully planned battle for East Coast passengers that would drive down air fares and pressure competitors to back away from some lucrative markets. It chose Providence, Rhode Island, just 60 miles from Boston's Logan Airport, thus tapping the Boston-Washington corridor. The Providence airport escaped the congested New York and Boston air-traffic-control areas, and from the Boston suburbs was hardly a longer trip than to Logan Airport. Experience had shown that air travelers would drive a considerable distance to fly with Southwest's cheaper fares.

As Southwest entered new markets, most competitors refused any longer to try to compete price-wise; they simply could not cut costs enough to compete. Their alternative then was either to pull out of the short-haul markets or be content to let Southwest have its market share while they tried to hold on to other customers by stressing first-class seating, frequent-flyer programs, and other in-flight amenities.

In April 1997, Southwest quietly entered the transcontinental market. From its major connecting point of Nashville, Tennessee, it began nonstops both to Oakland, California, and to Los Angeles. With Nashville's direct connections with Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland, Providence, and Baltimore-Washington, as well as points south, this afforded one-stop, coast-to-coast service, with fares about half as much as the other major airlines.

Two other significant moves were announced in late 1998. One was an experiment. On Thanksgiving Day, a Southwest 737-700 flew nonstop from Oakland to the Baltimore-Washington Airport, and back again. It provided its customary no-frills service, but a $99 one-way fare, the lowest in the business. The test was designed to see how pilots, flight attendants, and passengers would feel about spending five hours in a 737, with only peanuts and drinks served in flight. The older 737s lacked the fuel capacity to fly coast-to-coast nonstop, but with Boeing's new 737-700 series this was no problem. The Thanksgiving Day test was a precursor of more nonstop flights, because Southwest had firm orders for 129 of the new planes to be delivered over the next seven years. This would enable it to compete with the major carriers on their moneymaking transcontinental flights.

In November 1998, plans were also announced for starting service to MacArthur Airport at Islip, Long Island, which would enable Southwest to tap into the New York City market. By late 1999 it was flying to 54 cities in 29 states. Table 13.4 list the cities.

Table 13.4. Cities Served by Southwest, October 1999

Albuquerque | Hartford, CT[a] | New Orleans | Sacramento |

Amarillo | Houston (Hobby & | Oakland | St. Louis |

Austin | Bush Intercontinental) | Oklahoma City | Salt Lake City |

Baltimore/Washington | Indianapolis | Omaha | San Antonio |

Birmingham | Islip (Long Island) | Ontario, CA | San Diego |

Boise | Jackson, MS | Orange County | San Francisco |

Burbank | Jacksonville | Orlando | San Jose |

Chicago (Midway) | Kansas City | Phoenix | Seattle |

Cleveland | Little Rock | Portland | Spokane |

Columbus | Los Angeles (LAX) | Providence, RI | Tampa |

Corpus Christi | Louisville | Raleigh-Durham | Tucson |

Dallas (Love Field) | Lubbock | Reno/Tahoe | Tulsa |

Detroit (Metro) | Manchester, NH | Rio Grande Valley | |

El Paso | Midland/Odessa | (South Padre | |

Ft. Lauderdale | Nashville | Island/Harlingen) | |

[a] Service to Hartford began October 31, 1999. | |||

By mid-2002, with the 9/11 disaster still affecting airline travel, Southwest was the only major carrier that had been operating profitably in the 18 months since. U.S. airlines were posting losses of as much as $8 billion in 2002—eclipsing the record in 2001 of $7.7 billion, with the loss in the more profitable business travel being particularly acute. The high-cost airlines faced enormous pressure from low-fare carriers, most notably Southwest, but also from Internet sites that allowed bargain hunting. Southwest was now the nation's sixth-largest airline, and it had been profitable for 29 consecutive years.

In June 2001, just months before the September 11 attacks, Herb Kelleher retired. He was replaced by James Parker, who had joined Southwest in 1986, and Parker readily admitted that he was no Herb Kelleher. His immediate challenge was to contain the operating costs of soaring liability insurance and unionized workers' agitation for raises to match the rich contracts negotiated at other airlines before September 11. However, the bankruptcies of United Airlines and US Airways in late 2002 highlighted the need for airlines to slash billions in operating costs, notably through labor give-backs of extravagant union contracts, and this helped subdue new labor demands.[215]

In the increasingly brutal airline market, even Southwest was getting squeezed. It still remained profitable, and its seat capacity for the first half of 2004 was up 29 percent from four years earlier, but because of mounting price competition, revenue had risen only 18 percent during this time. It remained profitable while the worldwide airline industry had incurred losses of about $30 billion since 2001. But Southwest now faced price competition from a new breed of low-price competitors, such as JetBlue Airways, which offered amenities like inflight TV. The bigger airlines also were becoming more competitive, for they had substantially lowered their costs and their ticket prices. Some pilots on major airlines, with their compensation give-backs, were even making less than Southwest pilots. In this environment, CEO James Parker abruptly retired after only three years on the job. He was replaced in July 2004 by 50-year-old Gary Kelly, former chief financial officer of Southwest.

In early 2005 Southwest announced its invasion of the Pittsburgh market, taking advantage of US Airways' major service cuts there. This was the latest move in Southwest's continuing buildup in the East. It had entered the Philadelphia market in May 2004, and with its arrival traffic rose more than 51 percent and average fares fell more than 37 percent. Pittsburgh now had six low-cost carriers, and the dominant hub position of US Airways had eroded.[216]

Southwest also added Fort Myers, Florida, and Denver in 2005, and planned to offer flights to Washington's Dulles Airport by Fall 2006. Its Baltimore presence already tapped Washington's northern and eastern Maryland suburbs, and now Dulles would expose it to the burgeoning population in northern Virginia.

In these expansions into more competitive airports, the growth was nudging Southwest toward becoming a typical big airline. It even began testing whether it should move to assigned seating instead of its hallmark open-seating policy; early results suggested that assigned seating could shave a minute or so off boarding time, but would lead to more disappointed customers. Still, it had no first-class seating, no meals, and no posh airport VIP clubs. By the end of 2006, Southwest had 478 planes, more than United's 460 mainline jets. Long promoted as "the low-fare carrier," it had raised fares nine times since the middle of 2005, including a $10 increase on some flights over the July Fourth weekend.

CEO Kelly maintained that nothing was imminent, but "it's a matter of when, not if" Southwest will launch service to Mexico, Canada, or even the Caribbean. As it grew larger, change was threatening to dilute Southwest's efficiency built around its all-Boeing 737 fleet. The possibility of flying 100-seat jets to smaller markets was being considered. Further erosion of the successful bare-bones business plan seemed probable, such as adding some type of in-flight entertainment. The market niche as the lowest-fare carrier was eroding.

Several other factors threatened the bare-bones leadership. One was the end of Southwest's advantage over rivals in fuel costs. It had used contracts to lock in future fuel prices—a fuel-hedging program—and this saved $900 million in 2005, but would wind down in 2007. The other was largely a factor of its 60 consecutive quarterly profits by July 2006, a record of profitability unique in the industry. Labor negotiations loomed, and while Southwest's pilots were the highest paid in the industry, thanks to big pay cuts for pilots in the major airlines, Southwests' maintained that they had earned raises.[217]

By the end of 2006, the so-called legacy carriers had become reinvigorated. With their restructuring, often under the umbrella of bankruptcy, and the severe price cutting of previous years, they now had costs that only discounters previously could enjoy; in addition these major airlines had the premium overseas traffic that discounters did not have. This situation impacted stocks of JetBlue, AirTran, Frontier Airlines, and Southwest as they reported sharply lower profits.[218]

The business plan that had been so successful in the forty years before, now was challenged in an environment of aggressive low-price competitors as well as legacy carriers also competing on price. Southwest CEO Gary Kelly reduced expansion plans. Underperforming flights were moved to more lucrative routes. For example, daily flights from Baltimore to Cleveland and Providence to Phoenix were reduced, while flights to Denver added 14 daily arrivals. Nonstop flights on some routes, such as between Philadelphia and Los Angeles, and Baltimore and Oakland were even eliminated.

In addition to streamlining schedules and routes to maximize efficiency, Southwest sought to win more business travelers willing to pay somewhat higher fares for amenities, such as renovated boarding areas featuring roomier seats and power outlets, workstation counters with stools and flat-screen TV sets. Preferential boarding, bonus frequent-flier credits and free cocktail vouchers were offered in "Business Select" fares. The corporate sales team that promoted flying Southwest to company travel agents, was expanded to 15 people. The open boarding system was modified to issue passengers numbers dictating their order of boarding, thereby cutting time in line to five minutes from up to an hour. Further amenities were being considered, such as Internet access and movies or television.[219] The fear was that these moves toward the mainstream would compromise Southwest's uniqueness.

In March 2008, revelations about negligence with safety inspections and maintenance were to cause greater management concern than changing the boarding system or offering more amenities.

In early March 2008, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) accused Southwest of "serious and deliberate" safety violations, and proposed a $10.2 million fine, a fine believed to be the largest ever imposed on a major U.S. passenger carrier. The penalty stemmed from Southwest's negligence in continuing to fly 46 older Boeing 737s without the required inspections of the fuselage from June 2006 to March 2007. The inspections were aimed at finding cracks in aging planes that could bring down a modern jetliner. Six of the planes were found to have cracks, the longest a few inches, but these were not serious enough by themselves to bring down a plane. A week later, Southwest temporarily grounded another 38, after it could not determine whether an important safety inspection had been done properly.

Southwest had prided itself in never having a passenger fatality due to a crash. It was generally regarded as the best-run domestic airline. "They start off with a lot of money in the goodwill bank, and they make a really, really bad mistake," said a travel manager.[220] But Southwest's lapse was to be the tip of the iceberg: Other airlines soon had to ground their planes until tardy safety inspections were completed.

Invitation to Make Your Own Analysis and Conclusions

Your analysis, please, of CEO Kelly's contemplated new business plan for Southwest.

Do you think this inspection snafu will have any long-term effect on Southwest's public image?

Southwest has been undeviating in its pursuit of its niche. For years, while others tried to copy, none were able to fully duplicate it. For years, Southwest was the nation's only high-frequency, short-distance, low-fare airline. As an example of its virtually unassailable position, Southwest accounted for more than two-thirds of the passengers flying within Texas, and Texas was the second-largest market outside the West Coast. When Southwest invaded California, some San Jose residents drove an hour north to board Southwest's Oakland flights, skipping the local airport where American had a hub. And in Georgia, so many people were bypassing Delta's huge hub in Atlanta and driving 150 miles to Birmingham, Alabama, to fly Southwest that an entrepreneur started a van service between the two airports.[223]

Unlike many firms, Southwest did not permit success to dilute its niche strategy. It has not attempted to fly to Europe or South America, or to match the big carriers in offering amenities on coast-to-coast flights—Yet! In curbing such temptations, it has not sacrificed growth potential. It still has many U.S. cities to embrace. Despite its price advantage now being countered by low-price competitors and even by some major airlines desperately trying to reduce overhead to better compete with discount carriers on certain routes, Southwest is still the market leader in its niche.

Seek dedicated employees.—Stimulating employees to move beyond their individual concerns to a higher level of performance, a truly team-oriented approach, was by no means the least of Kelleher's accomplishments. The esprit de corps enabled planes to be turned around in 15 minutes instead of the hour or more of competitors; it brought a dedication to serving customers far beyond what could ever be expected of a bare-bones, cut-price operation; it brought a contagious excitement to the job obvious to customers and employees alike.

Kelleher's extroverted, zany, and down-home personality certainly helped in cultivating dedicated employees. So did his legendary ability to remember employees' names, his sincere interest in them and, of course, the company parties. Flying in the face of conventional wisdom, which says that an adversarial relationship between management and labor is inevitable with the presence of a union, Southwest achieved its great teamwork while being 90 percent unionized. It helped, though, that Kelleher started the first profit-sharing plan in the U.S. airline industry in 1974, with employees eventually owning 13 percent of the company stock.

Whether the high degree of worker dedication can pass the test of time, and the test of increasing size, is uncertain. Kelleher himself has retired, and his two successors have different personalities. Yet here is a model for an organization growing to large size and still maintaining employee commitment. In Chapter 2 we examined the leadership style of Sam Walton and the growth of Walmart to become the largest retailer.

The attainment of dedicated employees is partly a product of the firm itself, and how it is growing. A rapidly growing firm—especially when its growth starts from humble beginnings, with the firm as an underdog—promotes a contagious excitement. Opportunities and advancements depend on growth. And where employees can acquire stock in the company, and see their shares rising, potential financial rewards seem almost infinite. Success tends to create a momentum that generates continued success.

Can you identify additional learning insights that could be applicable to other firms in other situations?

In what ways might airline customers be segmented? Which segments or niches would you consider Southwest's prime targets? Which segments probably would not be?

Discuss the pros and cons for expansion of Southwest beyond short hauls. Which arguments do you see as most compelling?

Evaluate the effectiveness of Southwest's unions.

On August 18, 1993, a fare war erupted. To initiate its new service between Cleveland and Baltimore, Southwest announced a $49 fare (a sizable reduction from the then standard rate of $300). Its rivals, Continental and US Air, retaliated. Before long, the price was $19, not much more than the tank of gas it would then take to drive between the two cities—and the airlines also supplied a free soft drink. Evaluate the implications of the price war for the three airlines.

A price cut is the most easily matched marketing strategy, and usually provides no lasting advantage to any competitor. Identify the circumstances when you see it desirable to initiate a price cut and potential price war.

Do you think it is likely that Southwest will remain dominant in its niche despite the array of discount carriers? Why or why not?

What is your forecast for the competitive environment of the airline industry 10 years from now?

Herb Kelleher has just retired. And you are his successor. Unfortunately, your personality is quite different from his: you are an introvert and far from flamboyant, and your memory for names is not good. What would be your course of action to try to preserve the great employee dedication of the Kelleher era? How successful do you think you will be? Did the board make a mistake in hiring you?

Herb Kelleher has not retired. He is going to continue until 70, or later. Somehow, his appetite for growth has increased as he has grown older. He has charged you with developing plans for expanding into longer hauls, and maybe to South and Central America, and even to Europe. Be as specific as you can in developing the desired expansion plans.

How would you feel personally about a five-hour transcontinental flight with only a few peanuts, and no other food or movies? Would you be willing to pay quite a bit more to have more amenities?

The Thanksgiving Day nonstop transcontinental experiment went fairly well, although customers and even flight attendants expressed some concern about the long, five-hour flight with no food and no entertainment. No one complained about the price.

Debate the two alternatives of going ahead slowly with the transcontinental plan with no frills, or adding a few amenities, such as some food, reading material, or whatever else might make the flight less tedious. You might even want to debate the third alternative of dropping the idea entirely at this time.

The so-called legacy airlines were having resurging revenues and profitability by the end of 2006, to the detriment of Southwest and the other discount carriers. What is your assessment of the situation from Southwest's standpoint? Is this only a short-term phenomenon, or is the discounter model—low fares and rapid, mostly domestic growth—vulnerable long-term?

What is Southwest's current situation? What is its market share in the airline industry? Is it still maintaining a high growth rate? Has the decision been made to expand the nonstop transcontinental service, and have any changes been made in the no-frills service for this. How about international flights? Have other discount carriers, such as JetBlue, made any sizable inroads in Southwest's niche?

[201] Kevin Kelly, "Southwest Airlines: "Flying High with 'Uncle Herb'," Business Week, July 3, 1989, p. 53.

[202] Ibid., p. 53.

[203] Richard Woodbury, "Prince of Midair," Time, January 25, 1993, p. 55.

[204] Charles A. Jaffe, "Moving Fast by Standing Still," Nation's Business, October 1991, p. 58.

[205] Bridget O'Brian, "Southwest Airlines Is a Rare Air Carrier: It Still Makes Money," Wall Street Journal, October 28, 1992, p. A7.

[206] Jaffe, p. 58.

[207] "Passenger Flights Set Hopkins Record, Cleveland Plain Dealer, January 30, 1993, p. 3D.

[208] O'Brian, p. A7.

[209] Ibid.

[210] Subrata N. Chakravarty, "Hit 'Em Hardest with the Mostest," Forbes, September 16, 1991, p. 49.

[211] Wendy Zellner, "Striking Gold in the California Skies," Business Week, March 30, 1992, p. 48.

[212] Chakravarty, p. 50.

[213] Ibid.

[214] Kenneth Labich, "Is Herb Kelleher America's Best CEO?" Fortune, May 2, 1994, pp. 45–52.

[215] Scott McCartney, "Southwest Sets Standards on Costs," Wall Street Journal, October 9, 2002;DanielFisher, "Is There Such a Thing as Nonstop Growth? Forbes, July 8, 2002, pp. 82, 84.

[216] Melanie Trottman, "At Southwest, New CEO Sits in a Hot Seat," Wall Street Journal, July 19, 2004, pp. B1 and B3; idem, "Southwest Feels Squeeze," Wall Street Journal, August 23, 2004, p. B3; idem,"Southwest Will Fill US Airways' Pittsburgh Gap," Wall Street Journal, January 6, 2005, p. D9.

[217] Compiled from: Dan Reed, "At 35, Southwest's Strategy Gets More Complicated," USA Today, July 11,2006, pp. B1 and B2; Susan Warren, "Keeping Ahead of the Pack," Wall Street Journal, December 19,2005, pp. B1 and B3; and Susan Warren, "Southwest to Offer Flights to Dulles Starting This Fall," WallStreet Journal, April 5, 2006, p. B2.

[218] Melanie Trottman and Susan Carey, " 'Legacy' Airlines May Outfly Discount Rivals," Wall Street Journal, October 30, 2006, pp. C1 and C4.

[219] Susan Stellin, "Now Boarding Business Class," New York Times, February 26, 2008, p. C6.

[220] Compiled from Jeff Bailey, New Inspections Ground 38 Southwest Jets," New York Times, March 13, 2008, pp. C1 and C4; Andy Pasztor, "FAA Seeks to Fine Southwest $10.2 Million," Wall Street Journal, March 7, 2008, p A4; Andy Pasztor and Melanie Trottman, "Southwest Airlines CEO Apologizes for Lapses," Wall Street Journal, March 14, 2008, pp. B1 and B2.

[221] Jaffe, p. 58.

[222] Source: The idea of expectations affecting customer satisfaction was suggested by Ed Perkins for Tribune Media Services and reported in "Hotels Must Live Up to Promises," Cleveland Plain Dealer, November 1, 1998, p. 11-K.

[223] O'Brian, p. A7.