Herman Miller, Inc., an office-furniture maker based in Zeeland, Michigan, had long been a celebrated company, extolled by numerous business texts, including Tom Peters' best seller, A Passion for Excellence, and The 100 Best Companies to Work For in America by Robert Levering and Milton Moskowitz. Its furniture designs have been displayed in New York's Museum of Modern Art. It was a model of superb employee relations, and it stood in the forefront with environmentally sensitive policies. This company had been a paragon for almost seven decades.

But in the 1990s, circumstances began changing, and not for the better from Herman Miller's perspective. While sales had generally been increasing, although far from robustly, profits were seriously diminishing. Herman Miller remained the high-price, high-cost contender in an increasingly competitive market, and a market that itself was only expanding modestly. Amid these difficulties, one could wonder whether the enlightened approach to management might be turning out to be an albatross. Should it be modified or even abandoned?

D.J. DePree founded the company in 1923 in a small town in west-central Michigan. He named it Herman Miller after his father-in-law, who provided startup capital. For seven decades it was run by the DePree family, devout members of the Dutch Third Reformed Church, and they maintained a paternalistic relationship with their employees through the decades.

Early on, the family sought to set a kinder, gentler tone with employees, offering profit-sharing and employee-incentive programs long before they were fashionable. Along with this, participative management almost bordering on democracy was practiced. (See the following Information Box for a discussion of participative management.) This helped create a loyal work force that turned out well-made products that could be sold at premium prices.

Through the 1960s and 1970s, the company prospered with the expanding office furniture industry. D.J.'s sons, Hugh and Max, took the enterprise public but continued to nurture employees' commitment to the company. For example:

In the 1980s when hostile takeovers threatened many firms, the company instituted "silver parachutes" for all employees so that any who might lose their jobs would receive big checks.

It may be the only company in the United States to have had a vice-president of people.

In a time of escalating top executives' salaries by 1990 to as much as a hundred times companies' lowest wages, Herman Miller limited the top salary to no more than 20 times the average wage of a line worker in the factory.

Employees were organized into work teams and every six months both workers and their bosses evaluated each other.

In the middle 1980s, Max DePree, in the interest of ensuring the fullest career development of promising managers, announced that he would be the last member of the family to head up Herman Miller. Henceforth, the next generation of DePrees would not even be permitted to work at the company. See the following Issue Box for a discussion of the desirability of nepotism (favoritism granted by persons in high office to relatives and friends).

Of course, there had never been any serious efforts to unionize the work force.

Since 1968, the company had turned its attention to designing products for a so-called Action Office. It introduced components, such as desk consoles, cabinets, chairs, flexible panels and the like, that could give flexibility, and some degree of privacy, to the workplace. It emphasized innovative designs, and dealt with a number of "enormously gifted but extremely high-strung designers."[224] These vaulted Herman Miller into the top ranks of the industrial design world.

The company regularly budgeted between 2 and 3 percent of sales for design research, double the industry average. Sometimes its commitment to doing what was right (rather than what was best) brought it to a new level of corporate consciousness. For example:

In the 1970s, an enormously successful desk chair called the Ergon was introduced. Millions of these designed-for-the-body chairs were sold. Then an advanced desk chair called the Equa was proposed. It would cost about the same as the Ergon. At this point many companies would have scrapped it rather than cannibalize (take sales away from) their star. But Herman Miller introduced it nevertheless.

In March 1990, the Eames chair, the company's signature piece, was given a routine evaluation of the materials used. This was a distinctive office chair with a rosewood exterior finish, priced at $2,277. The research manager, Bill Foley, realized that two species of trees used, rosewood and Honduran mahogany, came from vulnerable rain forests. The decision was made to ban the use of these woods once existing supplies were exhausted, even though the CEO, Richard H. Ruch, predicted that this decision would kill the chair.[225]

Few firms have shown the concern for the environment that Herman Miller has. In addition to the rain forest example cited previously, here are several other instances of such concern:

The firm cut the trash it hauled to landfills by 90 percent since 1982.

It built an $11 million waste-to-energy heating and cooling plant, thus saving $750,000 per year in fuel and landfill costs.

Herman Miller employees used 800,000 styrofoam cups, material anathema to waste disposal. So it distributed 5,000 mugs and banished styrofoam. The mugs carried this admonition, "On spaceship earth there are no passengers . . . only crew."[226]

The company spent $800,000 for two incinerators that burned 98 percent of the toxic solvents coming from the staining of woods, thereby exceeding Clean Air Act requirements. CEO Ruch, under questioning from the board of directors for the costly exceeding of standards, stated that having the machines was "ethically correct."[227]

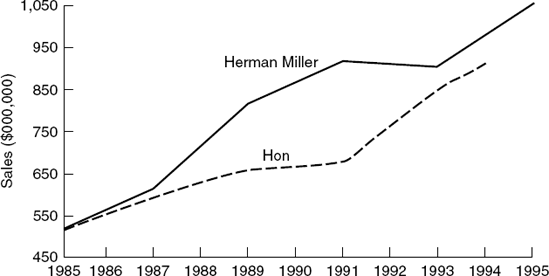

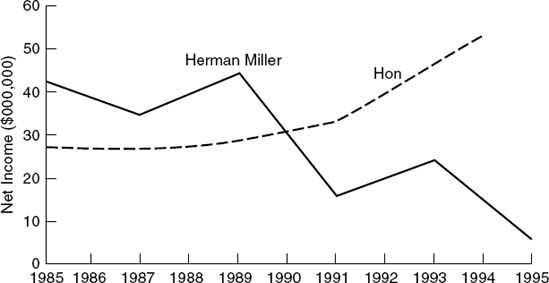

By 1995, Herman Miller was a $1 billion corporation. But given that its sales in 1989 had been almost $800 million, this was not a significant accomplishment, especially because profits had slid from over $40 million in most of the 1980s to $4.3 million in 1995. And in 1992, it recorded a net loss of $3.5 million, its first loss ever. Table 14.1 shows the trend in revenues for selected years from 1985 to 1995. Table 14.2 shows the net income disappointments during these years. Earnings by 1995 were 90 percent less, on higher sales, than in many years in the 1980s. And net income as a percent of revenues had been declining steadily since 1985, from 8.3 percent to only .4 percent in 1995.

Perhaps most indicative of the worsening performance of Herman Miller was in its "competitive battles." Hon Industries was such a close competitor, one with virtually the same size and aiming at similar markets. Table 14.3 shows the sales and net income of Hon during these same years. Unlike Herman Miller, Hon's profits had risen steadily, and net income as a percentage of revenues was two to three times better in the 1990s. Figures 14.1 and 14.2 show these competitive battles graphically.

Any top executive has to be concerned with the fortunes of the company's stock price, and the satisfaction of shareholders. While Hon Industries' stock price had climbed fourfold in the last decade, Herman Miller's barely moved: in 1985 its over-the-counter shares sold at $24; in 1995 they were about the same—this in the midst of the greatest bull market in stock market history.

Table 14.1. Herman Miller Revenues, 1985–1995

Millions | Percent Change | |

|---|---|---|

Source: Company public records. | ||

Commentary: While somewhat erratic, the increase in sales should hardly in itself be a cause for alarm. But this does not tell the whole story of Herman Miller's problems. See Table 14.2. | ||

1985 | $ 492 | |

1987 | 574 | 17.6 |

1989 | 793 | 38.2 |

1991 | 879 | 10.8 |

1993 | 856 | (2.6) |

1995 | 1,083 | 26.5 |

Table 14.2. Herman Miller's Total Net Income, and Percent of Sales, 1985–1995

Millions | Percent of Sales | |

|---|---|---|

Source: Company public records. | ||

Commentary: Here the trend is far more serious than in Table 14.1. The trend in total profits is steadily downward since the 1980s, despite the increase in sales during most of these years. While the results for 1995 are particularly troubling (and resulted in the chairman's "retirement"), of particular concern is the erosion of profi ts as a percentage of total sales. And this is not for a single year but for all of the 1990s. | ||

1985 | $40.9 | 8.3 |

1987 | 33.3 | 5.8 |

1989 | 41.4 | 5.2 |

1991 | 14.1 | 1.6 |

1993 | 22.1 | 2.6 |

1995 | 4.3 | .4 |

J. Kermit Campbell became the company's fi rst outsider CEO in 1992. He had had a 32-year career at Dow Corning. In an annual report, he seemed to espouse all the best values of the DePrees: "I truly believe that there is something in human nature that wants to soar."[228]

Table 14.3. Sales and Profit Performance of Major Competitor, Hon Industries, 1985–1994

Revenues (millions) | Net Income (millions) | Income as Percent of Sales | |

|---|---|---|---|

Source: Company public records. | |||

Commentary: Hon and Herman Miller are surprisingly close in total sales. If anything, Herman has been growing slightly faster than Hon. But looking at profits tells a different story. While Herman's profits have been eroding badly. Hon's have steadily been increasing. And the improvement in profits as a percent of sales for Hon is impressive indeed, while this is the great source of Herman Miller's trepidation. | |||

1985 | $473.3 | $26.0 | |

1987 | 555.4 | 24.8 | 5.5 |

1989 | 602.0 | 27.5 | 4.5 |

1991 | 607.7 | 32.9 | 5.4 |

1993 | 780.3 | 44.6 | 5.7 |

1994 | 846.0 | 54.4 | 6.4 |

Campbell was named chairman in May 1995 when Max DePree retired. He acted quickly to cut costs, and, in the process, to discharge several top executives. The head of Herman Miller's biggest division, workplace systems, a 20-year veteran, was let go. Also, the company's chief financial officer was removed. Campbell's goal was to pare selling and administrative costs to 25 percent from the current 30 percent.

He wanted to cut about 200 employees from a work force of 6,000, doing so through early retirements but also from firings. He closed plants in Texas and New Jersey, as well as several showrooms. At this point, Herman Miller was rapidly losing its reputation as one of the best companies to work for in America. But Campbell could point out that survival was more important than preserving a pristine worker relationship.

Campbell's tenure proved to be short. In mid-July, barely two months into his chairmanship, on the same day the company announced its annual results and the nearly 90 percent drop in profits from the previous year, his departure was also announced. What was not clear was whether the board was dissatisfied with Campbell's cost-cutting as being too little or too much.

In any case, the board named Michael Volkema as new chief executive. Volkema had joined Herman Miller in 1990 when it acquired cabinetmaker Meridian. He had the reputation of being driven and charismatic, and he was young—only 39. He had come to the board's attention for his cost-cutting efforts in the small Meridian operation ($100 million in sales).

The marketplace was hardly the same in the 1990s as it was in the heydays of the 1960s and 1970s. Sales of office furniture were not expected to grow at more than 5 percent, even if corporate profits remained high. A basic shift in demand was blamed for this: Computer technology required fewer layers of management, leading to general downsizing of office space needs.

Not only was total demand growing slowly, but the premium-end of the market, which had long been Herman Miller's niche, was also drying up as businesses in general chose to reduce costs by using lower-priced furniture.

In 1994, Herman Miller introduced a new Aeron chair, made from a mesh material that helped keep the body cooler. Although its design was unique and artistic, it retailed for up to $1,150, hundreds of dollars more than most other office chairs. Sales were disappointing.

Given limitations in the business market, the company saw opportunity in the home office sector. "We'll have 40 million to 50 million people working some part of their day at home," Campbell predicted. He hoped that the firm's quality image would be especially appealing to a significant part of this market.[229] So, the company introduced its first home office line, carrying a price tag of $1,799 for a desk. Early results were not promising; hundreds of OfficeMax and Office Depot stores featured fully acceptable desks for no more than $725.

Herman Miller's problem of arousing demand for its admittedly high-quality, well-designed furniture was further impeded by the company's traditional practice of doing very little product advertising. While such a strategy worked in decades past, was it still appropriate in the 1990s?

A central issue in the Herman Miller shift toward operational mediocrity and deterioration in recent years had to do with its enlightened management style toward both employees and the environment. Long the model for superb employee relations, Herman Miller faced the dilemma: In an age of impersonal cost-cutting and downsizing, can a company be competitive with altruistic policies that protect employees and the environment? Perhaps more to the point, were Herman Miller's problems the result of such policies being unrealistic today, or was something else wrong, something having little to do with employee relations and environmental concerns?

Let us address the crucial question: Do the best in employee relations add unacceptable costs? What employee relations are we talking about? Giving employees participation in many decisions? Giving them profit-sharing incentives? Giving them opportunities for advancement as far as their abilities will take them? Making them feel wanted and appreciated, and part of a team? Giving them a feeling of job security at a time when so many firms were downsizing and forcing many employees out, whether done under the guise of early retirement or outright forced discharges? Involving them with products they can take pride in? Do such things add to unacceptable costs against "lean and mean" competitors?

While these questions or issues could be debated at some length, perhaps the only question that really is a detriment to achieving necessary cost savings is that of job security. Some paring down might need to be done to stay competitive cost-wise, especially in a computer age where middle management and staff positions can be consolidated.

Unfortunately, management and workers alike must face the grim realities of today's environment: That their skills and experience may no longer be as needed today. That they must be prepared to shift their jobs and learn new skills, or be prepared for early retirement, no matter how enlightened the firm. To compete, it must be "lean" if not "mean." Such early retirements or terminations can be done harshly or empathetically. Empathetically suggests reasonable early retirement incentives, help with finding alternative employment or with the training needed to develop new skills. Counseling can be important—and time. Time to adjust to the harsh realities and to pursue alternative employment opportunities before being cast out. All these add some costs. But an organization does not have to be "mean" in seeking to be competitive. Can't a firm be kind to loyal employees, even if it adds a little to its costs temporarily?

Regarding the environment, did Herman Miller lose money by not using for its chairs certain tropical hardwoods found in rain forests? Maybe some; yet substitute woods should have proven acceptable to virtually all customers. Other costs, such as going beyond 1990 Clean Air Act requirements for incinerators and building an $11 million waste-to-energy heating and cooling plant, resulted in some cost savings, although not as much as the investments made. On the other hand, substituting reusable mugs for styrofoam cups resulted reportedly in cost savings of $1.4 million.[230] So, environmental concern and action does not have to result in major additional expenditures.

It seems, then, that indicting the altruistic policies of Herman Miller for its less-than-laudable recent operating results might be mistaken. Perhaps the blame rather lies in the aged strategy: high-quality, well-designed products, priced at the top of the market, with the major promotional reliance on word-of-mouth rather than advertising. What worked well in the 1980s and before may need to be reevaluated in the 1990s and beyond. This is more an age of austerity, with aggressive competitors and killer-category chains, such as Office Depot, offering good merchandise at prices half or less those of Herman Miller. In particular, perhaps Herman Miller should have tested the waters for medium-priced goods. It would not need—or want to—discard its quality reputation, nor abandon the high-end of the market. Rather, it could have expanded its offerings downward from the very high end.

Herman Miller also seemed to have miscalculated in the receptivity of the home-office market to its high-priced furniture. While undoubtedly a few wealthy individuals would willingly pay the steep price for a desk and other furniture of highest quality at the cutting edge of design, this market might not be very sizable.

Michael Volkema changed things for the better, after the painful downsizing and restructuring of Herman Miller in the industry slump of the mid-1990s. By the end of 2000, five years under Volkema, sales almost doubled to $1.938 billion and operating income went from $1.2 million to $140 million for a net profit percentage of 7.2 percent. Comparing with the major competitor, Hon Industries, revenues were almost the same, but Herman Miller's net income was well above Hon's of $106 million and net profit percentage of 5.2 percent.

In January 2000, Forbes selected Herman Miller to its "Platinum List," those exceptional corporations that "pass a stringent set of hurdles measuring both long-and short-term growth and profitability.[231]

Volkema had expanded the narrow high-end customer base to emerging and midsize businesses, and homes. In three years he spent more than $200 million on computer systems and other technology, aimed at assuring speedy delivery, and another $100-million-plus on research and development for new products. To attract consumers, a website was developed featuring office furniture specially designed for this market.

Employees were still catered to, with a bright and airy new plant in Holland, Michigan, where workers assembled furniture to music by U2, the Allman Brothers, and Sting. "A sign near the front door boasted that workers there haven't been late in shipping a single order in 75 days."[232]

By 2001, revenues reached beyond $2.2 billion, with net income $144 million, both statistics the best ever. Then the market collapsed in 2002 in the aftermath of 9/11. Since 2004, both revenue and income have shown steady gains, with fiscal 2006 having a 14.6 percent revenue gain, with net earnings 46 percent above the previous year.

Herman Miller was still widely recognized both for its innovative products and its business practices. In fiscal 2004 it was named recipient of the prestigious National Design Award for product design from the Smithsonian Institution's Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum. In 2005, it was again included in Business Ethics magazine's "100 Best Corporate Citizens," and was cited by Fortune as the "most Admired" company in its industry.[233]

Invitation to Make Your Own Analysis and Conclusions

How would you improve the business model of Herman Miller? Support your analysis and recommendations.

"A worker-sensitive firm is bound eventually to face a competitive disadvantage. It cannot control its labor costs." Evaluate this statement.

Do you see any risks in Herman Miller lowering its quality and its prices? Do you think it should have done so?

What do you think of the "enlightened" policy announced by Max DePree as he retired that henceforth no DePree will ever work for the firm again, in order that able people can have unimpeded career paths within the company? Discuss as many facets of this policy change as you can.

Evaluate the statement by Dunlap of Scott Paper that "I see no point in sacrificing 100 percent of the employees for the 35 percent who ought to leave."

What do you think of the decision to forego using an attractive wood, because it was taken from the rain forest that needed to be protected?

What would be your prescription for a successful change manager? You might want to compare with Campbell who only lasted two months at Herman Miller.

Before

Operating results for fiscal year 1987 have just come out. They show that netincome dropped 11.9 percent from the previous year and 19 percent from1985. What is even more troubling, net income as a percent of sales fell from8.3 percent in 1985 to 5.8 percent. What do you propose at this time?

After

It is July 1995. Chairman Campbell has just "resigned" under pressure fromthe board. You have been named his successor. What do you do now? (Youmay have to make some assumptions, but keep them reasonable and statethem specifically.) Don't be bound by what actually happened. Maybe adifferent strategy would have been more successful.

Debate both sides of the controversy of whether a firm with enlightened and em-pathetic employee relations can compete in a climate of aggressive competitors and severe downsizing.

What is the situation with Herman Miller today? Is Michael Volkema still chief executive? Has Herman Miller continued its turnaround? Can you find any recent information about its employee and environmental relations?

[224] Kenneth Labich, "Hot Company, Warm Culture," Fortune, February 27, 1989, p. 75.

[225] D. Woodruff, "Herman Miller: How Green Is My Factory?" Business Week, September 16, 1991, PP. 54–55.

[226] Ibid.

[227] Ibid.

[228] Justin Martin, "Broken Furniture at Herman Miller," Fortune, August 7, 1995, p. 32.

[229] Marcia Berss, "Tarnished Icon," Forbes, July 31, 1995, p. 45.

[230] Woodruff, p. 55.

[231] Brian Zajac, "The Best of the Biggest," Forbes, January 10, 2000, pp. 84, 85.

[232] "Reinventing Herman Miller," Business Week, April 3, 2000, p. EB88; and Ashlea Ebeling, "Herman Miller: Furnishing the Future," Forbes, January 10, 2000, pp. 94–96.

[233] Press release, June 28, 2006, http://www.HermanMiller.com.

[234] Kenneth Labich, "Why Companies Fail," Fortune, November 14, 1994, p. 53.