6

Human Resource Management Practices in Taiwan

In this chapter the human resource management practices in Taiwan will be introduced by nine sections, which are the background and development of HRM, the development stages of HRM, the strategic role of HRM, the key factors determining HRM practices, a review of HR practices, key changes in the HR function, key challenges facing HRM, what is likely to happen to HR functions in the next five years, and a case study of HTC, a worldwide known smartphone and tablet company in Taiwan.

Background and Development of HRM

Socio-economic Background of Taiwan

The island of Taiwan is located in the Pacific Ocean about 160 kilometers off the south-eastern coast of China, with Japan in the north and the Philippines in the south. In 2010 the population was approximately 23.162 million and the area was approximately 36,129 square kilometers, the combination of which made Taiwan one of the most densely populated areas in the world (640 persons/km2). Lacking natural resources, Taiwan has relied heavily on human resources for economic development. As a result of sustained economic growth over the past few decades, the per capita gross national product (GNP) of Taiwan has risen from US$97 per year in 1950 to US$19,155 in 2010, an almost 200-fold increase (Council for Economic Planning and Development, 2011).

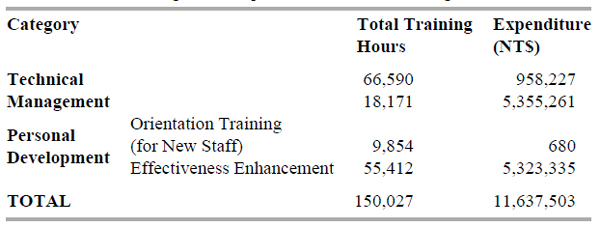

In the mid-1980s, the global economic boom greatly accelerated Taiwan’s economic growth, which registered annual percentage growth rates in the double digits. Taiwan’s export trade spurred on the vigorous development of the island’s manufacturing industry, which accounted for 39.4 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in 1986, the highest recorded percentage up to that point. From 1987 onward, export expansion slackened while domestic demand strengthened. The dampening of exports reversed industrial growth, resulting in an appreciable reduction in its share of GDP. The rapid expansion of domestic demand led to the rapid development of the service sector, whose relative importance in the economy rose tremendously (Huang, 2004) (see Figure 6.1).

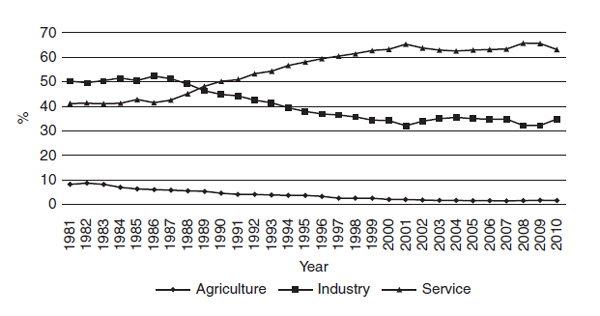

The employment structure also showed the same shift (see Figure 6.2). Agricultural employment declined from 18.8 percent in 1981 to 5.2 percent in 2010. Industrial employment reached a peak of 42.8 percent in 1987, but by 2010 it had dropped to 35.9 percent. Service employment has grown at a relatively stable pace over the years. It has been the largest share of total employment since 1988, increasing to 58.8 percent in 2010.

Figure 6.1 Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of Taiwan by Industry Structure (1981–2010)

Source: Council of Labor Affairs, Executive Yuan, Monthly Bulletin of Labor Statistics, various years

Figure 6.2 Employed by Industry Structure in Taiwan (1981–2010)

Source: Council of Labor Affairs, Executive Yuan, Yearly Bulletin of Labor Statistics, various years

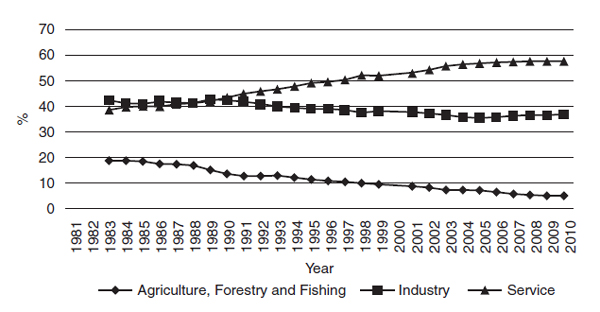

Taiwan’s civilian population of age 15 and over has risen from 10.8 million in 1978 to 19 million in 2010. During that same stretch of time, the labor force increased from 6 million to 11 million. At its peak, the labor participation rate (LPR) accounted for 60.93 percent of the civilian population (aged 15 and over) in 1987, and then decreased gradually to 58.1 percent in 2010 (Council of Labor Affairs, 2010). Taiwan’s unemployment rate by the late 1960s had fallen to below 2 percent, and Taiwan enjoyed a low unemployment rate for a long time (Directorate General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics, 2011). Although Taiwan’s economy was affected by the Asian Financial Crisis in 1998, its economic growth rate was 4.8 percent, higher than the growth rates of each of the other three Asian tigers (Hong Kong, South Korea and Singapore) (Directorate General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics, 2011; IMF, 2011; HIS Inc, 2012). In 2000, the unemployment rate dramatically increased to 2.99 percent and reached 5.2 percent in 2010. The main reasons for these statistical spikes included the influences of several unexpected important events, such as 1999’s 921 earthquake, 2000’s dotcom bubble, 2001’s 9/11 terrorist attacks, the Toraji and Nari Typhoons and 2008’s global financial crisis. However, in 2010, Taiwan’s economic growth rate reached 10.9 percent, the highest in the past 20 years (Council of Labor Affairs, 2010). Compared to 2009, an additional 2.1 percent of the population joined the labor force in 2010. Unemployed persons and the unemployment rate decreased from 639,000 people and 5.9 percent of the population to 577,000 people and 5.2 percent of the population (see Figure 6.3).

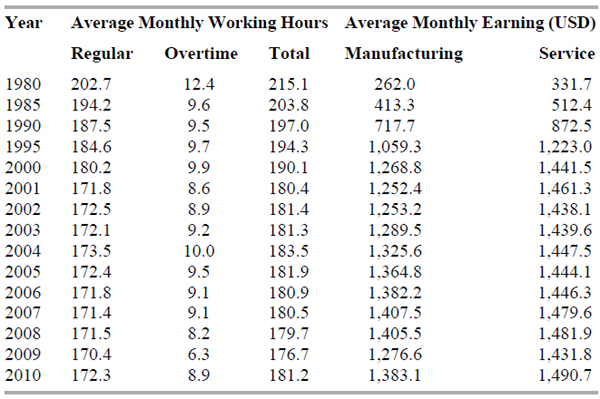

On average in Taiwan, the total monthly working hours of individual laborers throughout all industries decreased from 215.1 hours/month in 1980 to 181.2 hours/month in 2010; and on average in Taiwan, the total monthly earnings of individual laborers (1) in the manufacturing sector increased from US$262 in 1980 to US$1,383.1 in 2010 and (2) in the services sector increased from US$331.7 in 1980 to US$1,490.7 in 2010 (see Table 6.1). The fast growth of labor costs has contributed to the decline of Taiwan’s manufacturing sector, especially in Taiwan’s labor-intensive companies, many of which have transferred plants to Mainland China or southeast Asian countries. Taiwan is currently transforming itself from a labor-intensive industrialized economy to a capital- and technology-intensive industrialized economy.

Figure 6.3 Labor Force, Labor Participation Rate and Unemployment Rate in Taiwan (1978–2010)

Source: Council of Labor Affairs, Executive Yuan, Yearly Bulletin of Labor Statistics, various years

Without plentiful natural resources, one of the factors that contributed to the success of Taiwan is commonly considered to be the development of human resources. Therefore, Taiwan’s HRM development stages will be introduced in the following section.

Development Stages of HRM

Taiwan’s HRM development has proceeded through four stages. Stage I took place before the mid-1960s. In that period, HRM was a part of administration. Its major responsibilities were hiring, attendance and leave, payroll and employee welfare, and performance appraisal (Yao, 1999). According to Negandhi (1973), Taiwanese firms never stated or documented human power policies, never established independent personnel departments, seldom engaged in job evaluations, established no clear criteria for selection and promotion, based most promotions on age and experience, focused their training programs only on operatives, and relied on financial rewards as the main incentives for promoting worker productivity. Therefore, he concluded that the people-management practices in local Taiwanese firms could not effectively harness the available high-level human power.

Table 6.1 Working Hours and Monthly Earnings in Taiwan (1980–2010)

Source: Council of Labor Affairs, Executive Yuan, Republic of China, Monthly Bulletin of Labor Statistics, various years.

The second stage began in the mid-1960s and extended into the late 1970s. In that time, some US multinationals (for example, IBM, RCA and TI) and Japanese multinationals (for example, Matsushita and Mitsubishi) established operations in Taiwan while transplanting their home-country personnel-management practices. During the 1970s in Taiwan, there emerged some informal organizations that, devoted to personnel management, would meet regularly to exchange related information (Farh, 1995). Also during this same period, Taiwanese HRM tended to be operational and reactive: Its major responsibilities were hiring and retention, providing competitive packages and basic training programs, and maintaining harmonious employee–industry relations.

The third stage lasted approximately from 1980 to 2000. In this period, the HRM departments in Taiwanese firms began to play a stronger functional role, particularly in new areas such as personnel planning and control, management training, career development, and counseling for line managers. Human resources started to be viewed as a professional field. Active during this stage were two notable professional HRM organizations (Chinese Human Resource Management Associations and the Human Resource Development Association of the Republic of China (ROC)). Both of them organized and sponsored a number of seminars, workshops and training programs to promote modern HRM practices. In addition, the establishment of two academic institutions—the National Sun Yat-sen University and the National Central University—contributed extensively to HRM insofar as both of them offered master and PhD programs in the field (Huang, 2004).

The fourth stage started in approximately 2000 and is ongoing. Taiwan joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2002. To successfully survive in the twists and turns of competitive business environments, organizations have to adjust their strategies accordingly. During this stage, some HR departments became involved in the formulation of business strategies. The role of HRM transformed from administrative to strategic by providing value-added practices and by establishing mechanisms and contexts to facilitate organization change and development. The 2002 Human Resource Survey for Twelve Nations in Asia, conducted by the Towers Watson Company, showed that in more than half of 65 listed companies, HR had inked policies and practices reflective of core organizational values, established an evaluation system of HR effectiveness and invested in the development of HR professionals. Also, 40 percent of the sample companies had engaged in long-term human power planning (Byars and Rue, 2010).

The Importance and Strategic Role of HRM

According to Huang’s study (1998), HR managers in the late 1990s declared that HR departments’ most important contributions to organizations were training and development, followed by compensation and benefits, and then by HR planning. As the importance of HR topics increased, HR planning, training and development, and performance appraisal acquired the greatest emphasis.

Beaumont (1993: 16–17) defined ‘strategic’ as the type of HRM that makes human factors an integral part of broad-based, long-term planning for implementing an organization’s objectives. Strategic human-resource management (SHRM) implies a managerial orientation ensuring that human resources are employed in a manner conducive to the achievement of organizational goals and missions (Gomez-Mejia, Balking and Hardy, 1995).

Several Taiwan-based empirical studies have supported the assertion that SHRM can enhance firm performance. For example, Chi and Chang (2006) found that the HR role of strategic partners can be positively associated with firm performance, while the role of administrative experts can be negatively associated with organizational performance. Lee, Lee, and Wu (2010) argued that integrating HRM practices with business strategies can be positively associated with firm performance. The research results of Hsu and Leat (2000) also show that HRM policies can be integrated with corporate strategy and that HRM should be involved in decision making at a broad level.

The results of the 2008 Cranet Taiwan Survey show that, in Taiwan, 85.8 percent of organizations had an HR department and that 69.6 percent of those organizations that lacked an HR department tended to rely chiefly on administrative directors’ handling of HR practices. In addition, 67.1 percent of the people responsible for HR practices had a seat on the board of directors or in an equivalent committee. They were involved in different stages of the strategy-formation process: 50.9 percent were participants from the outset, 20.5 percent were participants through subsequent consultation, 21.8 percent were participants upon implementation of a particular project, and only 6.8 percent helped form strategy even though the organization had not consulted them.

Another critical requirement of SHRM is the full involvement of line departments in HRM functions and activities. SHRM emphasizes close coordination between such internal HRM functions as recruiting, selection, training, development, performance appraisal, and compensation. At the same time, HRM must be integrated with functions external to HRM departments such as marketing, finance, production, and research and development (Anthony et. al., 1996).

The results of Hsu and Leat (2000) show that some HRM decisions have been shared between line management and HR specialists and that line managers have had a particularly influential role in decisions regarding recruitment and selection, training and development, and workforce expansion and reduction. The results of the 2008 Cranet Survey show that in Taiwan major policy decisions on recruitment and selection (42.4 percent), training and development (45.1 percent), pay and benefits (39.4 percent) and industrial relations (30.9 percent) have been made primarily by HR departments in consultation with line managers, whereas major policy decisions on workforce expansion and reduction have been made primarily by line managers in consultation with HR departments (42.5 percent). That is, both line management and HR departments have primary responsibility for major HR policy decisions.

Key Factors Determining HRM Practices

HR practices are greatly influenced by external environments. Economy, demography, culture, education, and politics and governmental policies generally are primary factors.

Economy

Taiwan’s economy experienced several critical transformations, starting out as chiefly an agricultural economy (before 1960), then coming to rely on labor-intensive industries (1960–80) before expanding heavily into technology and service industries (1980–90) and most recently capital-intensive and knowledge-intensive industries (1990–present).

In addition to the difficulties stemming from a rapidly evolving economy, Taiwanese companies have faced a sometimes brutally competitive business environment. In order to obtain a further comparative advantage, many companies relocated their operations to low-wage countries, especially to mainland China and Southeast Asia (Zhu and Warner, 2001). Global competition is also reflected in the formation of regional economic arrangements such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the European Economic Community (EEC) and in the establishment of global economic arrangements such as the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and the World Trade Organization (WTO). Therefore, the need for knowledge and skill acquisition and upgrades, as well as diversification and internationalization, has become crucial to HRM.

Demography

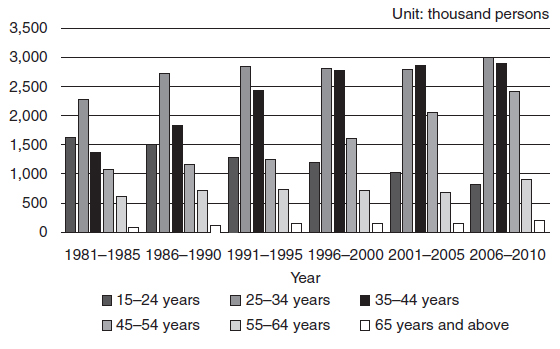

The population growth rate during the 1950s and 1960s was very high. However, as a result of the success of family-planning programs, the rate decreased dramatically to less than 2 percent in the 1970s and kept decreasing to around 1 percent in the 1980s. In 1998 it stood at 0.86 percent (Huang, 2004). It is expected that the older labor forces will increase as a percentage of the population and that young labor forces will decrease as a percentage of the population (see Figure 6.4). In the near future, a large number of employees will retire, and the subsequent benefits, retirement and succession issues will influence HR practices greatly. To reduce the negative impact of population structure change, companies would adopt outsourcing (41.5 percent), investment on autonomy (32.0 percent) and introducing foreign workers (29.5 percent) (Yan, 2006).

Culture

Confucianism is the most clearly identified traditional culture in Taiwan. Harmony, guanxi and paternalistic leadership are the major features of Taiwan’s Confucian business culture.

Harmony is one of the basic tenets of Confucian philosophy. It reflects an aspiration toward a conflic-free, group-based system of social relations. In order to maintain harmony and to save face in the workplace, managers generally handle with great delicacy any policy calling for the implementation of full performance appraisals or of highly individualized pay. Guanxi (relationship) is a distinctly East Asian feature that also existed in Taiwanese business operations. For example, the use of personal connections or networks is a popular method for recruitment and selection (Stone, 2009). In addition, Confucianism emphasizes hierarchy and status: Employees are expected to respect their supervisors; at the same time, managers are expected to be role models for subordinates by establishing sound rules for subordinates, fairly meting out rewards and punishments, and generally looking after the welfare of employees and their families, all of which reflects paternalistic leadership (Cheng, 1995). However, the influence of traditional culture seems to be declining owing to globalization, company size and type, and senior managers’ education and experience (Huang, 2004).

Figure 6.4 Employed Person by Age in Taiwan (1981–2010)

Source: Council of Labor Affairs, Executive Yuan, Yearly Bulletin of Labor Statistics, various years

Education

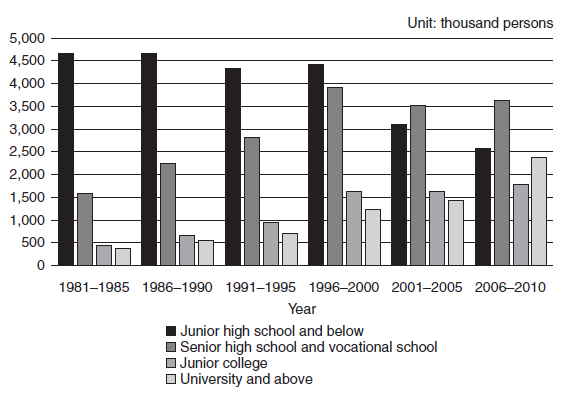

In 1970, Taiwan implemented nine-year compulsory education, and twelve-year compulsory education is to be implemented in 2014. In the past decades, the Taiwanese people’s average level of education has increased significantly; in particular, the number of employees whose education level went beyond a senior high school degree has grown during this period (see Figure 6.5).

The prevalence of higher-education attainment has improved the quality of the labor force, which has facilitated industry transformation. For organizations, higher levels of human capital mean better added-value knowledge and skills and better problem-solving capabilities, which enhance employee productivities. For example, the rapid expansion of college trained workers in production work suggests that increasing numbers of these workers are no longer working on assembly lines but instead are becoming highly skilled workers and technicians engaged in roles where independent judgment and problem-solving abilities are necessary (Lee, 2002). However, higher educational levels also result in employees’ higher expectations regarding job content, career development and rewards. Thus, the need for comprehensive HR practices increases as well.

Figure 6.5 Employed Person by Education Attainment in Taiwan (1981–2010)

Source: Council of Labor Affairs, Executive Yuan, Yearly Bulletin of Labor Statistics, various years

Politics and Governmental Policies

Legislative environments are coercive for organizations and yet are critical for HR functions. For example, in order to cope with the increase in production costs, many companies employ foreign workers with the permission of the government (up to 30 percent of their total employees) (Zhu, Chen and Warner, 2000). Labor laws generally cover the conditions of employment, labor relations, anti-discrimination matters and employment safety, which—in Taiwan—are the province of the Council of Labor Affairs in the Executive Yuan. The following are several major Taiwanese labor laws.

The Labor Standard Law (1985) is the most important base for HR policies, covering the areas of labor contracts, wages, working hours, leave-taking, retirement, compensation for occupational accidents and other terms and conditions of employment. The New Collective Employment Laws, including the Labor Union Law, the Collective Agreement Law and the Settlement of Labor Disputes Law were passed in 2010. They regulate the establishment, membership, officers, meetings, operational funds, supervision and protection of labor unions. Other important labor laws include the Employee Service Law (1992), the Gender Equality in Employment Act (2002), the People with Disabilities Rights Protection Act (2007), the Labor Insurance Act (1958), the Employment Insurance Act (2002) and the Labor Safety and Health Act (1974).

A Review of HR Practices

Staffing

This section describes Taiwanese companies’ staffing approaches, which include recruitment and selection methods, employee reduction and formal programs for enhancing labor participation and flexible job arrangements.

The results of the 2008 Cranet Taiwan Survey show that organizations have adopted different approaches to recruiting employees according to the type of employee being sought. At the time of the recent survey, the common methods preferred by company managers were internal recruitment (80.5 percent), commercial websites matching job positions with job-seekers (74.3 percent), recruitment agencies (48.7 percent) and company websites (44.3 percent). Job-seeking professionals tended to prefer commercial websites matching job positions with job-seekers (91.1 percent), company websites (61.3 percent) and internal recruitment (52.9 percent). For clerical job-seekers, commercial websites matching job positions with job-seekers (89.8 percent), company websites (58.4 percent), and internal recruitment (51.8 percent) were the most prominent methods used. Manual laborers in search of work were most likely to rely on commercial websites matching job positions with job-seekers (50.7 percent), job centers (45.3 percent) and speculative applications (38.2 percent). It is obvious that, nowadays, websites and internal recruitment have been the most common methods whereas use of advertising, word of mouth and educational institutions for employee recruitment has been relatively rare.

As to selection, although various kinds of methods have been developed, organizations have preferred to adopt traditional methods, such as one-on-one interviews and application forms oriented toward select knowledge and skills. For managers as of 2008, organizations used chiefly one-on-one interviews (85.4 percent), application forms (49.6 percent) and psychometric tests (42.0 percent). For professionals, one-on-one interviews (89.7 percent), ability tests (49.6 percent) and technical tests (42.0 percent) dominated. The preferences of clerical job-seekers were for one-on-one interviews (86.7 percent), application forms (55.3 percent) and ability tests (55.3 percent), and the preferences of manual workers seeking employment were for one-on-one interviews (46.9 percent) and application forms (37.2 percent). Overall these days, interview panels, references, assessment centers and graphology have played relatively small roles in selection processes.

In addition, organizations have decreased their number of employees in several ways. The 2008 survey shows that 71.2 percent of organizations used recruitment freezes; more than 50 percent used redeployment, non-renewal of fixed-term contracts and voluntary redundancies; and more than 20 percent used early retirement, compulsory redundancies, and outsourcing.

Organizations have provided recruitment, training and career programs for enhancing labor participation, especially for people with disabilities (50.0 percent, 25.7 percent and 8.4 percent respectively), women (33.2 percent, 27.9 percent and 18.6 percent respectively), and workers under the age of 25 (35.0 percent, 35.0 percent and 15.6 percent respectively). The same types of programs have also served ethnic minorities, older workers, women returning to the work-force after an absence and low-skill laborers.

More and more flexible job arrangements have emerged in the past several years. Atypical employment (such as temporary work and part-time work) has increased gradually. The most common forms of job flexibility—as of 2008—were overtime (92.9 percent), fixed-term contracts (72.6 percent), shift work (69.1 percent), weekend work (65.2 percent), temporary or casual work (56.4 percent), flexible hours (53.8 percent), and part-time work (36.6 percent). Other arrangements that have gained prominence include shared work, annual hourly contracts, tele-work, compressed work weeks and home-based work.

Training and Development

Taiwanese organizations have, in recent years, implemented training, career-development, and performance-appraisal programs, described as follows.

According to the 2008 Cranet Survey, organizations were spending an average of 3.63 percent of their annual payroll on training. Organizations were devoting an average of 7.2, 8.5, 5.9, and 5.6 days per year to training for managerial, professional, clerical and manual work respectively. Of all the organizations surveyed, 60 percent were systematically evaluating the effectiveness of training. The methods that organizations employed for evaluating training effectiveness included reaction evaluations immediately after training (73.6 percent), goal realization (71.4 percent), informal feedback from line managers (67.6 percent), informal feedback from employees (63.7 percent) and total number of training days (62.1 percent). Of less prominence were methods involving job-performance evaluations either months after or immediately after training, and evaluations of return on investment (ROI).

For career development, the methods that organizations generally used (according to the 2008 survey) were special projects (96.8 percent), projec-oriented team work (90.5 percent), cross-organization or cross-discipline tasks (87.3 percent), planned job rotation (83.6 percent), experience schemes (74.9 percent) and secondments to other organizations (72.6 percent). More than 50 percent of firms adopted mentoring, coaching, e-learning, succession plans, networking, formal career plans and high-flier schemes.

Of the surveyed organizations, 91.0 percent had a formal appraisal system for managerial employees, 92.7 percent had one for professional employees, 93.2 percent had one for clerical employees and 76.7 percent had one for manual employees. Immediate supervisor, supervisors’ supervisor and employee were ranked as the first three contributors—in order of importance—to performance management, regardless of position; subordinates, peers and customers also were part of raters sometimes. Organizations used appraisal data when making pay decisions (92.8 percent), training and development decisions (79.6 percent), workforce planning (67.0 percent) and career moves (51.6 percent).

Compensation and Benefits

Recent trends in Taiwanese organizations’ implementation of pay levels, incentive programs and benefits packages are described as follows. In general, pay levels are determined by a variety of factors, such as the external labor market, internal equity and employees’ seniority and performance. According to the 2008 Cranet Survey, three organizational entities—an organizational division, an individual within an organization and establishment/site—determined pay levels of managers, professionals, clerical workers and manual workers.

Incentive programs that managers were most likely to use when dealing with employees were bonuses based on individualized goals (73.5 percent), profit sharing (69.8 percent) and employee share schemes (64.0 percent). For professionals, the most popular incentive programs were bonuses based on individualized goals (75.7 percent), profit sharing (61.5 percent) and performance-based pay (56.2 percent). For clerical workers, the most popular incentive programs were bonuses based on individualized goals (69.5 percent), profit sharing (60.6 percent), performance-based pay (47.8 percent) and bonuses based on team goals (44.2 percent). For manual workers, the most popular incentive programs were bonuses based on individualized goals (46.6 percent), profit sharing (37.6 percent), performance-based pay (34.5 percent) and bonuses based on team goals (32.3 percent). Stock options and flexible benefits appeared to be less important. It is clear to see that bonuses based on individualized goals and profit sharing were the most commonly used incentive programs in businesses, regardless of which level employees hold.

Employees at organizations ranked types of benefits in the following order: maternity leave (91.6 percent), career-break schemes (90.2 percent), paternity leave (88.4 percent), training breaks (72.4 percent), parental leave (71.1 percent), pension schemes (63.1 percent) and private health-care schemes (32.4 percent). Workplace child care (8.9 percent) and childcare allowances (6.7 percent) were of considerably less importance.

Employee Relations and Communications

Trade unions did not play a significant role in the relationships between organizations and employees. Organizations communicated to employees by verbal means (96.8 percent), written missives (93.5 percent), electronic formats (89.4 percent), team briefings (73.3 percent) and representative staff bodies (50.7 percent). Employees communicated to organizations through immediate supervisors (98.6 percent), senior managers (86.9 percent), electronic formats (80.5 percent), attitude surveys (80.1 percent), regular workforce meetings (75.1 percent), work councils (74.0 percent), suggestion schemes (73.3 percent), team briefings (58.8 percent) and trade-union representatives (29.0 percent)

Only 21.5 percent of employees were members of a trade union. The results show that 64.1 percent of companies considered trade-union activity to have no influence on their organizations, and 77.2 percent stated that the influence of trade unions had remained the same during the past three years.

Key Changes in the HR Function

Taiwanese companies face intense global competition. They must have the ability to respond rapidly and effectively to unexpected but influential “black swan” events, such as the 2008 financial crisis. The McKinsey Quarterly (2007) identified the three most important factors affecting business operations: competition for talent, global and regional economic activities, and business connection with technology. For businesses, human resources factors are no less important than changes in an economic environment or the creation of highly competitive business performance.

Overall, the HR orientation of Taiwanese companies has gradually shifted from administration to strategy. In the past, companies focused mostly on the sub-functions of HR, operational activities and policy implementation, but in recent years companies have focused more on overall business management, strategic activities and decision-making participation (Wu et al., 2011).

Technology has also facilitated the transformation of HR’s role. First, human-resource information systems’ (HRISs’) digitalized administrative tasks, including payroll, attendance and insurance. Employees could maintain and update information on their own and therefore improved the effectiveness of the HR personnel. Second, HR portals could facilitate the sharing of personal information among employees and their supervisors for different purposes. Moreover, some companies have adopted outsourcing for activities such as training and recruiting, so HR professionals have more time for strategic and other value-added activities.

What follows is a series of descriptions regarding specific changes in the sub-functions of HR, staffing, employee development, compensation and employee relations.

Staffing

In the midst of globalization, Taiwanese companies have started to attract international talent, and the need to manage diverse employee populations has grown. For example, Taiwanese businesses that move to China must meet the requirements of related employment contracts and the five-year income plan (that is the average annual growth of income being no less than 15 percent) (Huang, Ci and Cheng, 2010). Also, China-based Taiwanese businesses must have the ability to manage local talent and a large number of employees (Chung and Wang, 2010).

Not only has the scale of operations grown for such businesses, but also most of them cannot directly replicate in China their previous successful Taiwanese experiences.

Another change involves e-recruiting, which is defined as using the Internet to disseminate recruitment ads and to attract job applicants. Many companies adopt this approach because of cost advantages over non-Internet recruitment strategies. HR-recruiting sites include corporate career websites, commercial websites, talent databases and various professional websites (Wu et al., 2011). The first two types of resources are the most commonly used in Taiwanese businesses (Sun et al., 2008).

In addition, owing to businesses’ need for human power flexibility and the imbalance between the supply of labor and the demand for skilled labor, more and more companies have extensively hired atypical employees (for example, dispatched employees, temporary workers) and have adopted flexible work schedules (for example, employee-tailored work weeks) (Noe et al., 2008).

Employee Development

The training systems of large and small companies develop in different directions. For large companies, their rapid expansion strains their efforts to find sufficient and adequate talent coming from the current education system and from company-based training mechanisms. Therefore, some large companies establish their own business universities (Ding, 2011). On the other hand, small and medium-size enterprises (SMEs) lack resources for large-scale talent development, and in response, the Council of Labor Affairs has promoted the Taiwan Train Quali System (TTQS), similar to International Organization for Standardization (ISO) certification, to help SMEs enhance their training quality and effectiveness (Council of Labor Affairs, 2010).

New training methods such as experiential learning and e-learning are available to many companies. The process of experiential learning takes a step-by-step approach to observation, reflection, summary and application. The purpose of experiential learning is to link games and work through personal involvement rather than through listening and watching in classrooms (Yan, 2011). Another factor influencing people’s learning is technology, such as web-based training (WBT) (Chung, Tsen and Yeh, 2008). Companies convey training content to their workers via the Internet, and employees choose and proceed through courses at their own pace. This method not only overcomes time and space constraints in physical classrooms but also creates learner-centered learning environments.

In traditional East Asian culture, the preservation of both inter-personal harmony and individual dignity has been a critical factor in governing performance-appraisal outcomes, which thus have been, at least until recently, unreliable as accurate reflections of employees’ real contributions. In recent years, however, due to intense competition, Taiwanese companies have started to recognize the importance of performance management. More and more companies have used the results for development purposes and have linked the results of performance appraisal and compensation to the goal of motivating employees.

Compensation and Employee Relations

Rewarding employees with bonus stocks at par-value has been a prominent characteristic of the Taiwanese high-tech industry but has come under heavy criticism for their possible threat to stockholders’ equity. After 2008, the employee bonus shares are recognized as company expenses and the receiving individuals are taxed by fair market value. This change has encouraged high-tech companies to use cash instead of bonus stocks for talent attraction and retention.

Many companies view incentive programs as important rewards. Take Hon Hai as an example: They have used organizational, departmental and individual performance as the basis for bonuses, such as performance bonuses, year-end bonuses, year-end banquet lotteries and bonuses for research and development (R&D) projects (Hon Hai Precision Ind. Co., Ltd, 2010).

In recent years, increases in vocational pressures coinciding with younger generations’ growing valuation of extra-vocational time have led Taiwanese to pursue higher-quality work experiences and better work–family balance. Benefits—in addition to salary and incentives—have become an important means by which companies can meet employees’ needs and can, thereby, achieve talent retention. Companies have developed a variety of benefit programs. Take TSMC’s Employee Assistance Program (EAP) as an example: They provide their workers with employee services, health centers and an employee-welfare committee. Employee services include a food court, a laundry service, dormitory security, transportation, an activity center, art galleries, bookstores, a coffee bar, a lounge and convenience stores; the health center provides outpatient services, health examinations, health seminars, health camps, nursing rooms and legal, relationship, and family counseling; the employees’ welfare committee provides a variety of clubs and associations, internal publications, emergency assistance, film and art activities, family days, children’s summer camps, coupons and kindergartens (Taiwin Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC, 2012).

Key Challenges Facing HRM

Ageing Population

In recent years, Taiwan has been experiencing the trends of high divorce rates, low crude marriage rates, late marriages and late childbearing; within this context, Taiwan’s fertility levels have been steadily decreasing, and the average age of the population has been increasing (from 34 years old in 2001 to 43 years old in 2011). The changes in the Taiwanese population’s age structure have not only influenced the supply of young workers but also influenced the size of consumer markets while hampering the development of businesses. Also, the increased number of older workers has led to a spike in the demand for related HR practices, such as life-long learning, opportunities for atypical employment and medical-care systems (San, 2011).

Low Labor Participation Rate

The LPR of Taiwan in 2009 was 57.9 percent, which is lower than that figure in most other developed economies, such as South Korea, Singapore, Japan, the United States, Canada, Germany and the United Kingdom. The female LPR of Taiwan was 49.6 percent in 2009, with more room for development than was available to male workers (San, 2011). Also, young Taiwanese have been entering the labor market later than traditionally because of longer educations and different work values. In addition, family–work conflict has created a situation where the percentage of Taiwanese women who are over 45 years old and returning to work after an absence is lower than the corresponding percentages in South Korea, Japan and the United States (San, 2011).

The Gap between School Education and Business Needs

The number of the college and above graduates increased rapidly in past decades (Figure 6.5); however, 28.4 percent of the unemployed are college graduates. Also, there has been a mismatch between the disciplines of higher-education institutions and the specialized demands of businesses—a mismatch that has been quite difficult to adjust to in the short term (San, 2011), such as the lack of technical manpower in traditional manufacturing. A related point concerns the upgrades that most Taiwanese vocational education institutions have undergone in recent years and that have blurred the distinctions between the general education system and the vocational education system, leading to a lack of skill-based workers (G. He, 2011). Also of interest is the fact that most research and development (R&D) talent potentially available to the Taiwanese business/industrial community has been shifting to other sectors of the economy. A case in point: 87.3 percent of Taiwanese PhD graduates chose to take on work at academic and research institutions in 2009 (San, 2011).

Weaknesses in Human Capital Investment for SMEs

The Taiwanese government’s expenditures on vocational training accounted for 0.02 percent of GDP in 2006, which is similar to the corresponding statistics for Japan and the United Kingdom. However, Japanese businesses have a legal obligation to provide their own workers with vocational training, and companies in the United Kingdom also train their own employees. In Taiwan, more than 98 percent of companies are SMEs and have less than 200 employees. Without either legal requirements for minimum expenditures or adequate resources, the companies’ investment in human capital is less than their counterparts in other economies (San, 2011). Plus the gap between school and business, as discussed above, has strengthened the importance of public training institutions in this area of concern.

Shortage of Professionals and Talent Recruitment

OEM (Original Equipment Manufacturing) was once the major strategy of Taiwanese manufacturing companies (Ceng, 2010); however, Taiwan is facing economic transformation and needs different types of labor. For example, the manufacturing industry needs software developers (Lin, 2011), semiconductor engineers, integrated-circuit design experts and green (energy-related) professionals (Ding and Gu, 2010); the service industry requires catering, logistics (Wang and Wang, 2011), and financial professionals (S. He, 2011); and the upgraded agriculture industry needs bio-tech and transportation professionals.

The results of the 2008 Cranet Survey in Taiwan show that succession planning and talent management have been the first two challenges besetting HR systems. The Talent Shortage Survey (Manpower, 2007) showed that the main reason for the turnover of middle-managers has been a lack of career-development programs. The vast majority of businesses in Taiwan are owned by single families; that is, the businesses exhibit no rigorous separation between ownership and management and, consequently, few businesses implement succession planning for high-level managers. In addition, the failure rate of foreign-company managers working for local firms is about 60 percent owing to irresolvable differences between their management philosophies (Li, 2011). Talent management is another issue. Lacking competitive compensation packages and the international working environment make attracting foreign talents more difficult. Moreover, Taiwanese expatriates generally lack satisfactory adaptability, regional-management, and sales capabilities (Gao, 2010).

Shortage of Entry-Level Laborers and Taiwan’s Foreign-Worker Policy

The development of technology has led to the polarization of the labor force: on the one end is professional talent and on the other is unskilled, entry-level labor. So that Taiwanese businesses have access to insufficient human power, the government and the private sector have adopted several approaches to the issue of labor supply (San, 2011). The Taiwanese government agreed to permit the entry of foreign workers into the island’s labor-supply pool beginning in 1992, and mandated that the basic-monthly-pay for workers would increase from NTD17,880 to NTD18,780 in 2012. Businesses have improved the safety of workplace conditions, as well as job security, fair labor practices and employee benefits. Also, businesses have adopted business process reengineering, outsourcing and automation in order to reduce the need for human labor. Although the labor-shortage problem has slackened, the situation remains unstable.

The Inflexibility of Atypical Employment

Taiwan is ranked 13th out of 139 economic bodies in the International Institute for Management Development (IMD) 2010 Global Competitiveness Report and 45th out of 183 economic bodies in the 2010 Doing Business Report. However, in terms of employment-flexibility indexes, Taiwan is ranked 153rd in the former publication and 114th in the latter (San, 2011). That is, the inflexibility of atypical labor contracts and atypical labor systems hampers not only the recruitment of foreign talent, but also the competitiveness of Taiwanese businesses.

The provisions for contracts in Taiwan’s Labor Standards Law are more restrictive than the terms in other developed countries’ corresponding laws. However, as Taiwan’s industries have evolved and Taiwan’s labor force has diversified, atypical employment there has become a notable trend. It is important for the Taiwanese government to review related policies and to provide a more friendly and flexible environment for workers and businesses (San, 2011).

Future of HRM in Taiwan

According to the 2011 Asian Competitiveness Annual Report announced by Beijing University of International Business and Economics Publishing Co., Ltd, Taiwan is ranked second, after South Korea, among 35 Asian economic bodies. The report states that the strength of Taiwan rests on the island-economy’s education and innovation systems.

To attract and develop talent for maintaining and even enhancing business-competitiveness advantages on the basis of current strengths is critical for Taiwanese businesses, especially in the turbulent economic environment that started in 2008. Of use at this point in the chapter would be a discussion, which follows, about the related trends of global talent development, work–life balance, new workforce dimensions and new technology.

Global Talent Development

Gunz and Peiperl (2007) surmised that from 2000 to 2040, as globalization progresses, the talented labors that companies seek will divide into three phases: expatriates, local talents and global citizen. In the third phase, global talent will search for job opportunities on the basis of personal experiences and career plans.

It has been predicted that the GDP of the Asia-Pacific region will account for approximately 45 percent of global GDP in 2015 (S. Li, 2010). Owing to emerging markets’ demand for specifically skilled labor, international companies— especially those based in China—have doubled their talent-recruitment efforts, often targeting Taiwan. The strengths of Taiwanese workers are their understanding of Chinese culture and business, their bilingual skills and their notable integration and innovation capabilities. The most popular areas in which Taiwanese workers exhibit notable skills are semiconductor engineering, LCD (Liquid Crystal Display) engineering and Integrated Circuit (IC) design. More and more Taiwanese professionals are willing to work in China because of the country’s rapid economic development.

Taiwanese companies are good at developing effective business models in order to take advantage of niche markets. However, they started to face different challenges when they went beyond Taiwan to engage in more large-scale operations in China where scalability of operation skills and business models is important (Li, 2011). Given that they speak the same language and have the same root of culture as Chinese mainlanders, the task of recruiting a large labor force and the follow-up training and development still pose a formidable challenge. The well-publicized multiple suicide incidents in Foxconn’s China factories in recent years reflected the need for more understanding on the subjects of stress management for employees in a high-pressure working environment, the enterprise–employee relationship in a fast-changing society, compensation augmentation at a very high pace, training of special skills for a large number of workers, and so forth.

The agreement between China and Taiwan to allow for direct cross-strait flights greatly strengthened the convenience of allocating skilled labor from one state to the other. The major types of workers that Chinese businesses need are entry-level workers, middle-level managers, and professionals. Regarding the growth of China’s internal markets, entry-level workers are for the rapid growth of the service industry, middle-level managers are for Taiwan experiences, and professionals are for sales and marketing, design, and the financial industry (You, 2010).

Balance Between Work and Life

According to the 2011 Neilsen Survey, the percentage of Taiwanese ranking work–life balance as the most pressing issue they face increased by 31 percent from the last such survey (The Nielsen Company, 2012). In Taiwan, per capita annual income was about US$20,000; however, Taiwanese workers generally put in more hours over the course of a year than do Chinese, whose per capita income was less than US$4,000. The employee productivity of Taiwan has increased more than that of China, South Korea, Hong Kong and Singapore in the past five years because of the long work hours and the stagnant wages and salaries in Taiwan (Chen, 2011). Taiwanese work hours added up to 2,074 hours per year in 2009, which is higher than the 1,911 hours per year in the United States. These figures imply that Taiwanese workers are under heavy stress. The common disorders stemming from work-related stress are psychosomatic disorders and generalized anxiety disorders. From 1998 to 2009, psychosomatic disorders underwent a fourfold increase in Taiwan. Generalized anxiety disorders afflicted 31.7 percent of Taiwan’s population of age 20 and over (Lin and Sie, 2011).

The highest risk segment of this population is female, young and working for flexible pay; also at high risk are those who work significantly long hours and get over-involved in their work, and those who lack job security. A total of 80 percent of female workers needed to take care of elders or children at home and, in general, female workers’ salary was only 80 percent of their male counterparts’ salary (He, Huang and Lu, 2010). The suicide events that happened in Foxconn during the years of 2010 and 2011, given that they all happened in China, also reflected the stress that this new generation of workers faces. Work-related strains for individuals, organizations’ emphasis on maximum efficiency and income and wealth disparities are all major contributors of stress for workers (Jiang and Huang, 2010).

More and more Taiwanese companies have started to increase the flexibility of employees’ schedules and have established and strengthened employee assistance programs (EAPs) and other types of programs aiming to help employees balance vocational responsibilities with life outside work. In addition, the Taiwanese government amended the Occupational Safety and Health Act in 2011, requiring employers to devote more resources to the physical and psychological health of employees. Companies with more than 50 employees must provide health-related services to employees. Also, employers are responsible for occupational injury if they cannot prove that they had provided appropriate protection such as protective clothing or equipment.

New Dimensions of the Workforce

The increase in older, female and atypical employees is a global trend. The high percentages of populations that are middle-aged or older have led to pressing financial problems. Potential solutions include increasing the birth rate, employing more immigrants and extending the retirement age of employees (Wu, 2010). These are some of the measures that promise to increase the supply of labor and counter the negative stereotypes about older and immigrant workers. In response to the need, the Taiwan Labor Standards Law, passed in 2008, extended the mandatory retirement age from 60 to 65.

The Council of Labor Affairs’ statistics showed that, among females, the labor-participation rate would peak for those aged from 25 to 29 and would subsequently decrease, mainly because women who were above that age would likely have extra responsibilities with respect to taking care of their newly formed families. Of women who exit the workforce after giving birth, the percentage who return to the workforce is far lower in Taiwan than in Europe, Japan and other regions. Taiwan’s Council of Labor Affairs also showed that in the United States, Canada, France, Germany, and other developed countries, women aged from 35 to 54 can maintain a high labor-participation rate of about 60 percent to 70 percent: For Taiwan, the rate of reemployment is only about 40 percent (Council of Labor Affairs, 2010).

A Women Employment Survey conducted by 104 Job Bank (2011), Taiwan’s largest online job site showed that, in Taiwan, 56 percent of female workers decided to return to the workplace within two years of taking family leave; however, companies generally considered that women could not simultaneously perform salaried work and care for their families (41 percent), while more women needed flexible working hours that were not provided by most companies (40 percent). In short, the stereotypes attached to mothers and the lack of time flexibility are two major obstacles that women face when returning to work after a family leave. While the LPR rate for Taiwan-based males has exhibited a downward trend, the rate for females has moved in the opposite direction. To improve their own business performance, businesses could make good use of their advantages, such as their sense of responsibility and their resistance to stress.

Atypical employment is another trend. In the past decade many businesses have sought greater flexibility for hiring employees, and dispatched employees or employees under contract are becoming more popular. Based on Huang’s study (2011), the number of employees in Taiwan’s industrial and service sectors in February 2010 increased by approximately 93,000 people compared to the number in the same month in the previous year. Of which, 18,000 were dispatched employees. Other forms of atypical employment such as temporary workers and short-term contractors have also gained in popularity. The first priority for some older and female workers seeking jobs is a flexible work schedule, which enables them to hold down a steady job without sacrificing their life outside the workplace.

New Technologies

New technologies such as the Internet affect business operations tremendously. In particular, notable features of Web 2.0—participation, sharing and interaction among users—influence HR practices in several ways. The core concept of “mass collaboration” of Web 2.0 is widely accepted. Underlying Web 2.0’s architecture is participation. The most well-known tools that serve this purpose are blogs, wikis, social networking sites (SNSs; for example, Facebook, Twitter and Plurk) and video-sharing sites (for example, YouTube and TED).

Web 2.0’s applicability to HR practices varies from recruitment and training to development and efficiency enhancement. Companies can use SNS to recruit employees and to check references. Moreover, companies can construct meaningful short videos that serve as teaching-material, thereby saving time and money. Worthy of note here is a study by Lytras, Castillo-Merino and Serradell-Lopez (2010). Using a sample of 2,029 SMEs, the researchers demonstrated that the efficiency of firms exhibited a significant improvement when the firms combined information and communication technologies (ICTs) with employee-assessment systems and other HR practices. These new tools are especially helpful in improving worker autonomy, flexibility of worker schedules and decentralization of decision-making processes within the firms.

Of the seven Web 2.0 principles that O’Reilly (2005) proposed, two of them —the “web as platform” principle and the “harnessing collective intelligence” principle—have important implications for innovation management. McAfee (2006) argued that email, intranet and portal are not the best tools for knowledge management, but Web 2.0 provides solutions. First, wikis can record knowledge in a work-in-progress form whose revision function promotes fast idea exchange. Second, effective usage of “tags” changes approaches to knowledge classification. Traditional taxonomies would set a first-level category, under which existed a second-level category; however, the bottom-up feature of tags reflects the actual cognition map of workers and also constitutes invisible links connecting workers to one another. Third, Rich Site Summary (RSS) enables workers to access dynamics knowledge for further knowledge accumulation. Fourth, workers can increase their weak-ties through their original strong-ties via SNS, which provides more opportunities to exchange heterogeneous ideas and to engage in innovation.

Case Study: Case Study: Beating out Apple and Samsung, HTC earns the “2011 Device Manufacturer of the Year” award

(The text of this case is summarized from the 2010 HTC Annual Report.)

Background Information

HTC was founded in Taiwan in May 1997. It sustained expansion in overall business operations and HTC’s brand development crowned HTC’s experiences. They shipped 24.67 million smartphones in 2010, the first time in their history where shipments surpassed the 20 million mark; that is, the firm more than doubled their 2009 shipment record, giving HTC a year-on-year growth rate much higher than the sector average. Net profits after taxes for the year reached NTD39.5 billion, to set a new all-time record. By the close of 2010, global recognition of the HTC brand had risen to 50 percent.

HTC today holds the attention of many global businesses and many exponents of technology media. Bloomberg Businessweek, Fast Company and MIT’s Technology Review put HTC on their respective lists of the world’s 50 most innovative companies in 2010 (Einhorn and Amdt, 2010). That same year, T3 magazine proclaimed HTC its “tech Brand of the year” (Mayne, 2011). Also that year, Newsweek named HTC one of the top ten innovative companies. At the 2011 Mobile World Congress, HTC overcame competition from Apple and Samsung to earn the “Device Manufacturer of the Year” award. In October 2011, Interbrand Company announced HTC as the 98th global brand, estimating their brand value to be about US$3.605 billion, having increased 163 percent over the previous year.

Human Resources

Employees represent one of HTC’s most valuable assets. The company has in recent years actively recruited outstanding talent into its ranks, particularly in the areas of product design, user interface, brand promotion and sales and marketing. While bringing on professionals from Europe and the Americas, they have also invested significant resources into making the work environment at HTC diverse, challenging and encouraging. As of the close of March 2011, HTC employed 12,943 staff worldwide, and 22.9 percent of all HTC managerial positions were held by 218 non-Taiwanese managers. Non-Taiwanese managerial and technical staff filled 13.5 percent of HTC managerial and technical positions. Women have held 16.2 percent of HTC’s 951 managerial positions since the company’s inception. HTC has consistently devoted considerable resources to in-house R&D capabilities. Today, R&D professionals account for almost 30 percent of HTC’s headcount, and annual R&D investments regularly represent 4 to 6 percent of total revenues.

At HTC, the Division of Talent Management handles corporate HR development and administration, promotes HTC corporate culture and employee benefit programs, and conducts organizational and HR planning to support corporate development.

Hiring and retaining exceptional employees is a key objective of HTC’s HR strategy. They are an equal opportunity employer and recognize the practical benefits that employee diversity brings to HTC corporate culture and to the reinforcement and extension of innovation. HTC hires all new employees through open selection procedures, with candidates offered positions based on merit. HTC works through cooperative programs with universities, internship programs and summer work programs to provide work opportunities to a large number of students each year. They participate actively in job fairs and recruitment events in Taiwan and abroad as part of their ongoing, organized effort to tap the best talent available.

For employee retention, HTC offers incentives to employees possessing special skills in order to keep them with the company and to ensure that they benefit from their employer-oriented efforts. Long-service awards are presented at a company-wide ceremony that recognizes employees with five- and ten-year-long service records. In order to enhance employees’ professional experience and career planning, HTC facilitates employee transfers within the company.

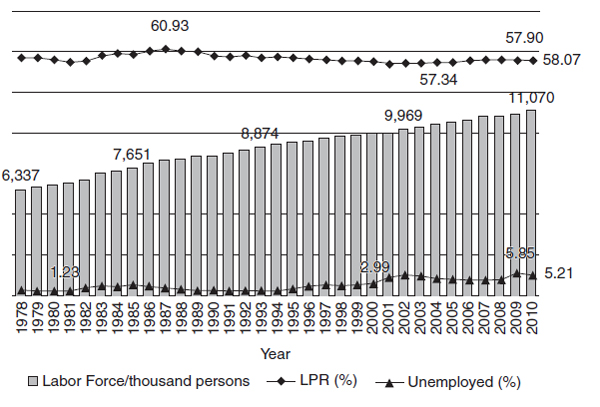

Employee Development

HTC operates a workplace environment highly conducive to learning and professional growth. By encouraging employees to improve themselves and to maintain and enhance their professional skills, HTC helps sustain its competitive advantage while keeping a promise to help employees grow as individuals. Supplementing their extensive in-house technical training curriculum, HTC offered its employees in 2010 specially designed management and personal development curricula (including language training and new-staff orientation) to help employees diversify their skill sets, explore new potentials and deepen expertise. HTC has also launched a dedicated e-learning and mobile learning platform able to deliver a diverse range of learning tools within a highly accommodating learning environment. HTC further has offered its employees in-service training scholarships, effectively subsidizing off-site training to encourage growth and permit the pursuit of personal fulfillment (see Table 6.2).

Compensation and Benefits

HTC employees earn market-competitive salaries that take into consideration academic background, work experience, seniority and current professional responsibilities. On the basis of HTC’s current-year business performance, the president proposes—and the board of directors approves— the amount of funds to be set aside for the annual employee-performance bonuses. The firm also allocates employee profit-sharing bonuses to employees each year on the basis of motions that derive from the board of directors and that are adopted by resolution at annual shareholders’ meetings.

The Labor Pension Act (the “Act”), which provides for a new defined contribution plan, took effect on July 1, 2005. Employees can choose to remain subject to the defined benefit pension mechanism under the Labor Standards Law (the “Law”) or can choose to be subject instead to the Act. The Act mandates that the rate of a company’s required monthly contributions to an employee’s individual pension accounts shall be at least 6 percent of the employee’s monthly wages salaries, and that these contributions shall be identified as pension expenses in the employee’s income statement.

Employee Relations and Communications

HTC’s work environment is geared to challenge, stimulate and fulfill employees. The company maintains various outreach initiatives designed to motivate employees, enhance employee benefits and facilitate greater dialogue between the company and its workforce.

HTC is committed to fostering an atmosphere of trust in its labor relations and assigns great importance to internal communications. HTC further offers employees various channels through which to submit opinions, suggestions and complaints, which may be delivered via a telephone hotline, an email address or physical mail—all of which are made known through HTC’s regular employee opinion surveys.

Future Challenges

HTC is now an important player in global telecommunications, and anticipates continued growth in the smartphone sector. HTC is responding to intense competition, and in this regard the company’s future efforts will continue to focus on tailoring innovative products ever more closely to users’ daily lives and on winning over increasing numbers of consumers.

In order to achieve long-term sustainability and competitiveness, HTC in 2010 acquired the software-customization house Abaxia. HTC made this acquisition specifically to broaden and deepen its capabilities in software development, integrated cloud computing and the development of varied connected services. HTC also announced a great recruitment plan in the first half of 2011: The company’s goal is to hire more than 1,000 R&D employees, equal to 30 percent of the current research team.

It is a big challenge for a fast-growing international company to effectively manage its employee talent, especially so large a number of R&D personnel, foreign workers and high-level managers. To balance discipline and innovation at the same time is the other challenge for any team to pursuit high performance. HTC, with its past record of achieved excellence, carries the promise of a bright future for all smartphone consumers.

Useful Websites

104 Assessment Expert: www.104assessment.com.tw/service.jsp

104 Job Bank: www.104.com.tw

1111 Job Bank: www.1111.com.tw

Adecco: www.adecco.com.tw/index.asp

Asia-Learning: www.asia-learning.com

Bureau of Employment and Vocational Training: www.evta.gov.tw

Bureau of Labor Insurance: www.bli.gov.tw

Career Consulting: www.career.com.tw

China Human Resources Development Academic Society: www.hrda.tidi.tw

Chinese Human Resource Management Association: www.chrma.net/eng/index. php

Chinese Management Association: www.management.org.tw

Chinese Personnel Executive Association: www.hr.org.tw

China Productivity Center: www.cpc.org.tw

Council of Labor Affairs: www.cla.gov.tw

e-job Bank: www.ejob.gov.tw

Kung-Hwa Management Foundation: www.mars.org.tw

Manpower Group: www.manpower.com.tw

Taiwan Academy of Management: www.taom.org.tw

Taiwan TrainQuali System: http://ttqs.evta.gov.tw/Default.aspx

Yes123 Job Bank: www.yes123.com.tw/admin/index.asp

References

Anthony M. S., Clarkson, R. B., Hughes, C. L., Morgan, T. M. and Burke, G. L. (1996) ‘Soybean is flavones improve cardiovascular risk factors without affecting the reproductive system of peripubertal rhesus monkeys’, The Journal of Nutrition 126: 43–50.

Beaumont, P. B. (1993) Human Resource Management: Key concepts and skills. London: Sage.

Beijing University of International Business and Economics Publishing Co., Ltd (2011, May) The Research Institute of Boao Forum for Asia: Asian Competitiveness Annual Rreport 2011. http://english.boaoforum.org/u/cms/www2/201109/07135115oewz.pdf, accessed February 1, 2013.

Byars, L. L. and Rue, L. W. (2010) Human Resource Management. KY: Muze Inc.

Ceng, R. (2010) ‘Goodbye, 5 Electronic Companies’, Business Weekly, 1191: 114–22 (in Chinese).

Chen, Y. (2011) “‘Jin’ Indisputable Force”, CommonWealth 464: 98–104 (in Chinese).

Cheng, B. (1995) ‘Chaxu geju (concentric relational configuration) and Chinese organizational behavior’, Indigenous Psychological Research in Chinese Societies 3: 142–219 (in Chinese).

Chi, N. and Chang, H. (2006) ‘Exploring the Relationships Between Human Resource Manager Roles, HR Performance Indicators and Organizational Performance’, Journal of Human Resource Management 6(3): 71–93 (in Chinese).

Chung, M., Tsen, H. and Yeh, F. (2008) ‘The Study of the Effectiveness of Web-Based Training’, Taiwan Business Performance Journal 2(1): 119–40 (in Chinese).

Chung, Y. and Wang, W. (2010) ‘The Limit of Blood-and-Iron’, Business Weekly 1176: 114– 24 (in Chinese).

Council for Economic Planning and Development (2011) Taiwan Statistical Data Book 2011. Taiwan: Council for Economic Planning and Development, www.cepd.gov.tw/m1.aspx?sNo=0015742, accessed February 1, 2013.

Council of Labor Affairs. (2009, May 27). Yearly Bulletin. Taiwan: Council of Labor Affairs. www.cla.gov.tw/cgi-bin/siteMaker/SM_theme?page=49c056e1, February 1, 2013.

Ding, S. and Gu, S. (2010). ‘Three Emerging Areas of Shortage’, CommonWealth 451: 56–60 (in Chinese).

Ding, Y. (2011) ‘Domestic enterprises, “corporate universities”‘, Management Magazine 444: 38–39 (in Chinese).

Directorate General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics (2013, January) Monthly Bulletin Of Statistics. Taiwan: Executive Yuan, http://eng.dgbas.gov.tw/lp.asp?CtNode=1998&CtUni t=1053&BaseDSD=35&mp=2, accessed February 1, 2013.

Einhorn, B and Amdt, M. (2010, April 15) The 50 Most Innovative Companies. www.business-week.com/magazine/content/10_17/b4175034779697.htm, accessed February, 1, 2013.

The Epoch USA, Inc (2011, May 18). ‘Taiwanese Women Who Turnover After Marriage 9 to 5 Intend to Return to the Workplace’, http://tw.epochtimes.com/b5/11/3/8/n3190862p.htm (in Chinese), accessed February 1, 2013.

Farh, J. (1995). ‘Human Resource Management in Taiwan, Republic of China’, in L. F. Moore and P. D. Jennings (eds), Human Resource Management on the Pacific Rim: Institutions, Practices and Attitudes. Berlin, New York: de Gruyter, pp. 265–294.

Gao, F. (2010). ‘Two Wings for the Talent’, Management Magazine 427: 102–03 (in Chinese). Gomez-Mejia, L. R., Balking, D. B. and Cardy, R. (1995) Managing Human resources. New York: Prentice-Hall International, Inc.

Gunz, H., and Peiperl, M. (2007) Handbook of Career Studies. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

He, G. (2011). ‘Three Times Competitive—I was Highly Paid’, CommonWealth 473:102–04 (in Chinese).

He, G., Huang, Y., and Lu, J. (2010) ‘Affairs of State? Family? A Woman Thing?’, Common-Wealth 451: 82–87 (in Chinese).

He, S. (2011) ‘What Kinds of People Would the Boss Want?’, Business Weekly 1,217: 116–17 (in Chinese).

Hon Hai Precision Ind. Co., Ltd. (2010) Welfare. Taiwan: Hon Hai Precision Ind. Co., Ltd, www.honhai-hr.com.tw/welfare.htm (in Chinese).

Hsu, Y. and Leat, M. (2000) ‘A Study of HRM and Recruitment and Selection Policies and Practices in Taiwan’, International Journal of Human Resource Management 11(2): 413–435.

HTC (2011, April 17) 2010 HTC Annual Report. Taiwan: HTC. www.corpasia.net/taiwan/2498/annual/2010/CH/2010%20HTC%20Annual%20Report%20(C)_FkajQyaI-qnNf_C4rBALHNJEiL_FfQr7JnnHEkj_uMunDAc3kJCR.pdf (in Chinese), accessed February 1, 2013.

Huang, T. (1998) ‘The strategic level of human resource management and organizational performance: Empirical investigation’, Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources 36(2): 59–72 (in Chinese).

Huang, T. (2004). Human Resource Management, 7th edn, eds L. L. Byars and L. W. Rue. Taipei: McGraw Hill (in Chinese).

Huang, T. (2011). Human Resource Management, 10th edn, eds L. L. Byars and L. W.Rue. Taipei: McGraw Hill (in Chinese).

Huang, T., Ci, D. and Cheng, S. (2010) Human Resource Management: Theory and practice, 3rd edn.Taipei, Taiwan: OpenTech (in Chinese).

IHS Inc. (2012). IHS Global Insight: Country and Industry Forecasting. Colorado: IHS Inc, www.ihs.com/products/global-insight/country-analysis, accessed February 1, 2013.

International Monetary Fund (IMF) (2011) IMF elibrary-data. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund, http://elibrary-data.imf.org.

Jiang, Y., and Huang, J. (2010) ‘High-voltage failure, the dilemma of a new generation of management’, CommonWealth 448: 36–39 (in Chinese).

Lee, F., Lee, T. and Wu, W. (2010) ‘The relationship between human resource management practices, business strategy and firm performance: evidence from steel industry in Taiwan’, The International Journal of Human Resource Management 21(9): 1,351–1,372.

Lee, J. S. (2002) Human Resource Development and Taiwan’s Move towards a Knowledge-Based Economy. Taiwan: The Pacific Economic Cooperation Council.

Li, S. (2010) ‘Taiwan staged to grab people’s congresses combat’, Management Magazine 434: 68–71 (in Chinese).

Li, Y. (2011) ‘Organizational transformation—the boss to do, or to introduce the CEO of?’, Business Week 1,236: 36–40 (in Chinese).

Lin, S. (2011) ‘Technology industry to get people—cottage[s] provide[d]? to lure them away to dig to [in?] China’, Business Weekly 1,227: 58–62 (in Chinese).

Lin, S. and Sie, M. (2011) ‘Health Killer—Psychosomatic Disorders’, CommonWealth 473: 128–37 (in Chinese).

Lytras, M. D., Castillo-Merino, D. and Serradell-Lopez, E. (2010) ‘New Human Resources Practices, Technology and Their Impact on SMEs’ Efficiency’, Information Systems Management 27(3): 267–273.

McAfee, A. (2006). Enterprise 2.0 – the dawn of emergent collaboration, MIT Sloan Management Review 47(3): 21–28.

McKinsey Quarterly, The (2007, November) The Organizational Challenges of Global Trends: A McKinsey global survey. London: McKinsey & Company, http://download.mckinsey quarterly.com/organizational_challenges.pdf., accessed February 1, 2013.

Manpower (2007, April 9) 2007 Talent Shortage Survey Results. Wisconsin, United States: Manpower Inc, www.manpower.com.tw/pdf/talent_shortage_2007_en.pdf, accessed February 1, 2013.

Mayne, M. (2011, September 8). HTC Scoops Top Gongs at T3 Gadget Awards 2010. www.t3.com/news/htc-scoops-top-gongs-at-t3-gadget-awards-2010, February, 1, 2013.

Negandhi, A. R. (1973) Management and Economic Development: The Case of Taiwan. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff.

Noe, R. A., Hollenbeck, J. R., Gerhart, B. and Wright, P. M. (2008) Fundamentals of human resource management, 3rd edn. New York: McGraw-Hill Irwin.

O’Reilly, T. (2005, September 30). What is Web 2.0. California: O’Reilly Media, Inc, www.oreillynet.com/pub/a/oreilly/tim/news/2005/09/30/what-is-web-20.html, accessed February 1, 2013.

San, G. (2011) ‘Retrospect and Prospect of Taiwan’s human resources planning,’ Yan Kao Shuang Yue Kan 35(2): 71–93 (in Chinese).

Stone, R. J. (2009). Managing Human Resources: An Asian Perspective, 1st edn. Milton: John Wiley & Sons.

Sun, S., Lou, Y., Chao, P. and Wu, C. (2008) ‘A study on the factors influencing the users’ intention in human recruiting sites,’ Journal of Human Resource Management 8(3): 1–23 (in Chinese).

The Neilsen Company (2012, February 27) ‘Consumer confidence, concerns and spending intentions, http://nl.nielsen.com/site/documents/NielsenGlobalConsumerConfidenceQ12012.pdf, accessed February 1, 2013.

TSMC (2012) Employee and People Care. Taiwan: Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, www.tsmc.com/english/csr/employee_and_people_care.htm, accessed February 1, 2013.

Wang, Y. and Wang, S. (2011) ‘Recruiting! 58% increase in the Job vacancy’, Global Views Monthly 299: 200–06 (in Chinese).

Wu, Y. (2010) ‘Seventy-year-old retired is not too late’, CommonWealth 458: 181 (in Chinese).

Wu, B., Wun, J., Liao, W., Huang, J., Han, J. and Huang, L. (2011) Human Resource Management: Basis and Application, 1st edn. Taipei, Taiwan: Hwa Tai Publishing (in Chinese).

Yan, C. (2011) ‘Experiential learning method like the real thing’, Management Magazine 446: 84–87 (in Chinese).

Yan, J. (2006). The Reuse of the order Retired Professional Human Resource: The orientation of enterprise requirements, unpublished master’s thesis, National Chengchi University, Taiwan (in Chinese).

Yao, D. (1999). ‘Human resource management challenges in Chinese Taipei’, Human Resource Management Symposium on SMEs Proceedings 2: 30–31.

You, Z. (2010) ‘New Cross-Strait Their Jobs Report,’ Business Weekly 1,156: 88–94 (in Chinese).

Zhu, Y., Chen, I. and Warner, M. (2000) ‘HRM in Taiwan: An empirical case study’, Human Resource Management Journal 10(4): 32–44.

Zhu, Y. and Warner, M. (2001) ‘Taiwanese business strategies vis a vis the Asian financial crisis’, Asia Pacific Business Review 7(3): 139–156.