13

Human Resource Management in the Fiji Islands

Introduction

The human resource management (HRM) environment of the Fiji islands has changed a lot since its independence in the 1970s and has undergone rapid changes in the recent decade. Both endogenous and exogenous environmental factors are closely knitted to the dynamism in the HRM environment. In Fiji, personnel management is practised by micro and small businesses, HRM practices are adopted by medium enterprises and strategic human resource management (SHRM) practices are practised in large organisations (Naidu, 2011b). This chapter is divided into seven sections. This first section of this chapter outlines the historical development of personnel management, industrial relations, employment relations, HRM and SHRM in the Fiji islands. The second section outlines the role of various institutions such as the state, trade unions, employer associations, non-government organisations (NGOs), donor agencies and trade agreements in the HRM environment. The third section outlines the endogenous and exogenous environmental factors that affect HRM practices. The fourth section discusses key changes in the HRM functions. The fifth section examines the key challenges and the future of HRM in the Fiji islands. The final section provides a case study of Paradise Manufacturers Fiji Limited within the context of the SHRM environment present in the Fiji islands.

Throughout this chapter, the discussions are designed to effectively distinguish the personnel management, HRM and SHRM in the micro and small businesses, medium and large enterprises and public sector organisations. The HRM practices within these sectors are homogenous; however, the HRM practices across these sectors are heterogeneous.

Historical Development of Personnel Management, Industrial Relations, Employment Relations, HRM and SHRM

The industrialisation process can be traced back to the 1870s, when the indentured labourers came to the Fiji islands to work on the sugarcane plantations (Prasad, Hince and Snell, 2002). In total, 60,965 workers were transported from India to the Fiji islands (Gillion, 1962). The indentured labourers from India brought with them a new culture, new norms and values and new ways of performing tasks. This marked the start of the era of personnel management adopted by the British Colonial rulers. During the era of personnel management, the indentured labourers were harshly treated and made to work on the sugarcane plantations for long hours (Gillion, 1962). There was a five-year contract between the indentured labourers and the British rulers and this contract was known as the girmit. Women were usually molested and harassed by the British rulers and the indentured male labourers, subsequently resulting in high suicide and illegal birth rates (Gillion, 1962). Throughout the colonial period, the Colonial Sugar Refinery (CSR), an Australian monopoly, controlled all the economic resources of the sugar industry. The monopolistic position of the CSR, coupled with brutal British rulers, further degraded the working conditions of the indenture labourers (Prasad, Hince and Snell, 2002). For instance, the management of labourers by the CSR was a challenging task. This company tried to keep the wages of the labourers as low as possible in order to increase the profits and return to the investors. The personnel administration model of the CSR emphasised dividing the workers based on caste structures, importation of labourers from India and harbouring of racist attitudes (Snell, 2000).

Similar to the sugar industry, the other sectors such as gold, manufacturing and agricultural were also constrained with staggering labour conditions and corporal punishments from the British rulers. In the gold mining industry, the Emperor Gold Mines Ltd, also an Australian monopoly, began operations in Vatukoula in 1954 by drawing labour from all 14 provinces of the Fiji islands (Prasad, Hince and Snell, 2002). The working conditions at the Emperor Gold Mines Ltd have been poor and dangerous for the workers, resulting in deaths, injury, industrial conflicts and loss of productivity.

Workers started organising and forming trade unions in the sugar and public services in the 1930s. This marked the start of an era of industrial relations (Prasad, Hince and Snell, 2002). In the 1920s, trade unions started emerging in the sugar and later on in the mining and manufacturing sectors. With the enactment of the Industrial Association Act, formal trade unions started arising by the late 1940s. In 1951, all the trade unions were consolidated into one single umbrella body known as the Fiji Industrial Workers’ Congress (FIWC). The FIWC is currently known as the Fiji Trades Union Congress (FTUC). A major industrial dispute between the Oil and Allied Workers Union and the oil companies in 1959 clearly demonstrated the urgency to strengthen the labour legislation and institutions in the Fiji islands (Prasad, Hince and Snell, 2002). For instance, in the mining sector, there was increasing bitterness among the trade unions and the Emperor Gold Mines Ltd from 1950 to the 1960s. This contributed to widespread industrial sector unrest (Leckie, 2003) resulting in a decline in productivity, worker morale and economic growth. As a result of this conflict, the Fiji Employers’ Consultative Association (FECA) was formed.

In 1960, the trade unions were able to exert pressure on the Colonial government in order to develop proper law and labour practice in the Fiji islands. This marked the start of employment relations. During the 1960s, key reforms of labour legislation were initiated and collective bargaining agreements were extended to the private enterprises (Prasad, Hince and Snell, 2002). The establishment of the Fiji National Provident Fund (FNPF) in 1968 brought together the employers, employees and the government in a tripartite forum for the overall management and administration of this scheme. For instance, in FNPF, the Board of Directors (BOD) is a tripartite body, with two trade union representatives, two employer representatives and two government representatives, and the chairman of is the Permanent Secretary for Finance (ILO, 2010). Similarly, the Training and Productivity Authority (TPAF) was established as a tripartite organisation to provide training to workers and to upgrade workers’ skills.

On 10 October 1970, the Fiji islands gained independence from British rule and adopted the Westminster system of political democracy (Prasad, Hince and Snell, 2002). The independence of the Fiji islands marked a major change from personnel management to HRM in large organisations. The HRM model from the 1970s to the late 1990s was based on the principles postulated and enacted under the following nine pieces of labour legislation: Employment Act 1965, Trade Unions Act and Trade Unions (Recognition) Act 1998, Trade Union Disputes Act and Trade Union Disputes (Amendment) Decree 1992, Sugar Industry Act 1984, Health and Safety at Work Act 1996, Wages Council Act 1985, Shop (Regulation of Hours and Employment) Act 1964, Industrial Associations Act and Factories Act 1971. In the case of micro and small businesses, these legislations were poorly implemented while in the case of medium and large enterprises (including multi-national corporations), these legislations were properly implemented (Naidu, 2011b). The personnel management model in micro and small businesses are largely determined by the discretion of the owner or manager. In the majority of instances the micro and small business owners or managers have policies for annual leave and hours of work, but the effective implementation of these policies is dependent on the owner or manager. For instance, the majority of the restaurants in Fiji are small in nature and are family owned. According to the owners or managers of these restaurants, implementing employment law may not be cost effective and economically viable for these businesses due to their smallness and their limited access to resources (Naidu, 2011b).

After the 1980s, large organisations began to change their practice from personnel management to HRM and since the 1990s, as a result of the influence of HRM from Australia and New Zealand, SHRM began in the Fiji islands. In order to survive in the dynamic environment, organisations from both the private and public sectors are aligning their HRM policies and practices with the goals, missions and objectives of the organisations. Furthermore, from 2007, the SHRM model of the Fiji islands evolved around the Employment Relations Promulgation (2007) (ERP 2007). The ERP (2007) is an employment act that is based on the following five guiding principles (Naidu, 2012a):

- creating the labour standards that are equally fair to both employers and employees

- eliminating discrimination from the workplace • providing the structure for collective bargaining and dispute resolution for employers and employees

- establishing institutions such as the Employment Relations Tribunal and the Employment Relations Court for dispute resolution

- fostering labour management consultation and cooperation.

Employers in Fiji are required to adhere to the ERP (2007) as it establishes the minimum standards for industrial relations and HRM policies and practices. The HRM policies and practices of organisations in Fiji have to be aligned to the ERP (2007). Once the HRM policies and practices have been aligned to the ERP (2007), then the next step is aligning HRM policies and practices with the goals, missions and objectives of the organisation. This employment law emphasised equality, integrity, transparency, teamwork, consultation and cooperation among the HRM partners. The ERP (2007) is properly implemented in the public and some sections of the private sector. In the case of the micro and small businesses in the private sector, the ERP (2007) is poorly implemented, whereas in the case of medium and large enterprises, the ERP (2007) is properly implemented (Naidu, 2011b; Naidu, 2012a; Naidu 2012b). A major change in the SHRM model occurred during September 2011 when the Essential National Industries (Employment) Decree was implemented by the military-led interim government. This decree requires existing trade unions to re-register as trade unions, trade union representatives to be workers of the designated corporations that they represent, and all existing collective bargaining agreements to be null and void 60 days after the implementation of the decree (Ministry of Labour Fij, 2011). This decree also has a provision for re-negotiation of the collective bargaining agreements if the employer is suffering from operating loss for two consecutive years. For instance, the employers have more avenues for aligning the HRM practices towards the goals and objectives of the organisation because the newly implemented Essential National Industries (Employment) Decree has more employer benefits as compared to the employee benefits (Naidu, 2011a, 2011b, 2012a, 2012b).

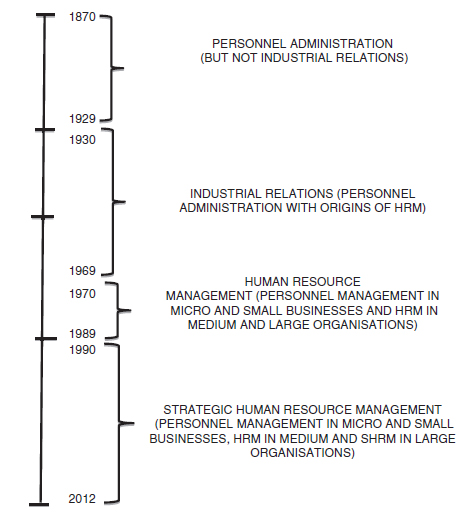

Figure 13.1 shows the historical development of HRM from personnel administration (PA)/industrial relations (IR)/employment relations (ER). It has been organised in chronological order. In summary, Figure 13.1 shows that from 1870 to 1929 personnel administration was practised in Fiji followed by industrial relations, employment relations, HRM and SHRM. The transition from personnel administration to SHRM occurred in a lapse of more than 100 years.

More specifically, the transition from industrial relations to employment relations and later to HRM and SHRM occurred on an average of 10 to 20 years. However, the transition from personnel administration to industrial relations took 59 years. For example, during the personnel administration period, Fiji was under British rule, hence it was challenging for the personnel administration model to evolve to ndustrial relations as the British rulers used brutal employee management practices.

Source: Council of Labor Affairs, Executive Yuan, Yearly Bulletin of Labor Statistics, various years

HRM Partnership

There are six key national actors in the HRM partners in the Fiji islands. These six actors are the state, trade unions, employers, non-government organisations, donor agencies and trading partners. Out of the six key actors, the state is the most important. The other five have equal importance in determining the HRM model of the Fiji islands. The following sections will provide an overview of the role of each of the actors.

State: The state’s primary role is to design and implement essential labour legislations. The Fiji islands’ contemporary HRM model is largely influenced by the Essential National Industries (Employment) Decree 2011 (see section 2.0). Some of the sections of the ERP (2007) are still in force while other sections have been abrogated by the implementation of the Essential National Industries (Employment) Decree 2011. The state also ensures that institutions (Employment Relations Court and Employment Relations Tribunal) are established in order to provide effective dispute resolution machinery. In addition to this, the state also establishes the minimum benchmark for HRM policies and practices for employment leave, compensation, employment benefits and grievance procedures. Another essential role of the state in HRM partnership is the role of surveillance and monitoring. The state through the Ministry of Labour ensures that labour legislation is effectively implemented. For instance, the Ministry of Labour carries out training for employers on employment law that is implemented in the country. This ministry also monitors organisations to ensure that employment law is effectively implemented in the country (Naidu, 2012a).

Trade unions/Employees: There are two trade union umbrella bodies: the Fiji Trades Union Congress (FTUC) and the Fiji Island Council of Trade Union (FICTU) in the Fiji islands. Initially, the members of the FICTU were members of the FTUC. A total of 15 trade unions who were disenchanted with FTUC combined to form the rival body of FTUC known as FICTU (Prasad, Hince and Snell, 2002). The officials of FTUC usually participate in tripartite forums that are involved in the design and implementation of labour laws. Other roles of trade unions include the representation of employee interests, influencing government on issues affecting employees and negotiating collective bargaining agreements (Elek, Hill and Tabor, 1993). The implementation of the Essential National Industries (Employment) Decree 2011 had major impact on the powers of trade unions. The trade unions are currently influencing the government to re-instate the powers that it had under the ERP (2007). For example, the National Secretary of FTUC is unhappy on the implementation of the Essential National Industries (Employment) Decree 2011 and emphasised that FTUC is currently working on protecting the trade union rights and reinstatement of ERP (2007) in all sectors of the economy (Anthony, 2011).

Employers/Employer associations: Currently, there is a single employer association in the Fiji islands known as the Fiji Employers and Commerce Association (FECA), formerly known as the Fiji Employers Federation. The FECA was formed in 1960 with 11 employers after the dispute between the oil industry and the Oil and Allied Workers Union (Prasad, Hince and Snell, 2002). The primary aim of FECA is to foster free trade and commerce activities for economic sustainability. Other activities of FECA include (Fiji Employers and Commerce Association, 2011: 1–2):

- providing a tripartite forum for consultation and collaboration on issues affecting employers

- establishing interdependent networks among employers

- promoting training of members.

For example, the CEO of FECF stated in a press statement that FTUC should engage in dialogues with the government rather than engaging in destructive lobbying with international trade unions, in order to solve the trade union crises that have aroused from the implementation of the Essential National Industries (Employment) Decree 2011. Any industrial actions by international trade unions will affect trade and communications as well as travel and the tourism industry (Chaudhary, 2011).

Non-government organisations (NGOs): NGOs such as the Fiji Women’s Rights Movement (FWRM), the International Labour Organisation (ILO), United Nations Human Rights (UNHR), United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and Save the Children Fund have an impact on the HRM partnership. These NGOs influence the government on child labour and equal employment opportunity legislations. Together with the state, the ILO plays a key role in providing capacity building to the tripartite constituents, technical assistance for the review of employment law, the implementation of programmes aimed at human resource development, and in tackling child labour issues via education of children. Currently, Fiji has ratified 31 labour conventions, out of which 28 are in force. For example, before an employment law is gazetted in Fiji, it is discussed at the ILO meeting by the representatives from the government, employers and the employees. Once all parties have reached mutual agreement, the employment law is gazetted and implemented in Fiji (ILO, 2012).

Donor agencies: The major donor agencies giving funds to Fiji are Australian Aid (AusAid), New Zealand Aid (NZAid), the European Union (EU), Japan and China. The aid programmes of these donor agencies are primarily directed towards delivery of essential social services, rural development, improving access to financial services, improving livelihoods and supporting sustainable development of the developing countries for the optimistic drive towards achieving Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) (Chand and Naidu, 2010). These donor agencies influence the government on laws, policies and practices towards the focus area of aid programmes. For example, the 2005 to 2010 NZAid policy still remains in force even though the partnership between the NZ and the Fiji government is frozen after the political turmoil of December 2006. The current NZAid policy is focused on promoting democracy and assisting people in squatter and non-squatter settlements in Fiji (ILO, 2010).

Trade agreements: Trade agreements such as the Melanesian Spearhead Group (MSG), the Pacific Island Countries Trade Agreement (PICTA), the Interim Economic Partnership Agreement (IEPA), the South Pacific Regional Trade and Economic Cooperation Agreement (SPARTECA) and the Pacific Agreement on Closer Economic Relations (PACER) have an impact on the HRM partnership in the Fiji islands. These economic agreements are based on conditions and rules of origin that influence employers and government to take a certain course of action in order to benefit from the trade agreements. For example, under the rules of origin of the SPARTECA agreement, Australia and New Zealand offer duty free, unrestricted or concessional access for all products originating from Fiji. The garment investors from China in Fiji produce the garments in Fiji at a higher cost as compared to China and export the garments to Australia and New Zealand in order to benefit from SPARTECA. These investors are not allowed to ship the garments produced in China to Fiji and re-ship these garments to Australia and New Zealand. In order to reduce the cost of production and increase profits, the Chinese garment factories import the Chinese workers to Fiji and make them work under very restrictive working conditions (Chand, 2011). Another example is the suspension of Fiji from the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF), which had a devastating impact on the PACER-Plus negotiations. Fiji was suspended from the PIF due to the deteriorating human rights issues in the country after the December 2006 coup (PIF, 2009).

Factors Determining HRM Practices

Similar to other small island developing states in the Oceania region, the HRM practices in the Fiji islands are largely affected by endogenous and exogenous factors. Endogenous factors include those variables that are determined by other variables in the system while exogenous factors include those variables that are determined by other variables outside of the system (Pathak et al., 2005; Schuler and Jackson, 2007). The exogenous factors include political, social and economic conditions and the endogenous factors include the characteristics of the work-force, competitive dynamics and characteristics of the company. The exogenous and endogenous factors that affect the HRM practices are all interdependent with one another (Budhwar and Debrah, 2001; Budhwar and Sparrow, 2002). The following section will provide an overview of the endogenous and the exogenous factors that affect the HRM factors.

Economic factors: Out of all the endogenous and exogenous factors discussed below, economic factors have the most severe impact on the HRM practices. The primary motive of the private sector is to maximise profits, hence the adoption of HRM practices is dependent on the economic situation of the company. Over the last five years, the annual growth rate of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has been negative; hence employers are adopting cost-cutting and rigid HRM practices. When the economy tightens up, the employers focus more on unilateral decision making, reducing the power of trade unions and cutting down on general employment benefits. The global economic shocks from the Greece and Italy debt crises and the slowdown of the European Union and American economies are also having an adverse impact on the HRM practices adopted by organisations in the Fiji islands. For example, the global financial crisis has had a major impact on the tourism industry of Fiji, clearly indicated by the decline in tourist numbers. According to Reddy (2010), the global financial crisis affected the tourism industry of Fiji, evidenced by tourist numbers declining from 585,031 in 2008 to 542,186 in 2009. This resulted in micro and small tourist operators closing down or cutting down on labour costs. Cutting down on labour costs was in the form of making workers redundant or suppressing employees’ wages (Sziraczki, et al., 2009).

Political and legal factors: The state is the major player in the political and legal environment because they establish the benchmark for the HRM practices in both the private and public sectors. Political and legal affairs such as government stability, international relations of the government and labour laws have a direct impact on the HRM practices adopted by organisations in the Fiji islands. For instance, in large multi-national corporations, such as British American Tobacco (BAT), the ERP (2007) and the Essential National Industries (Employment) Decree 2011 has an impact on the HRM practices adopted by the Fiji-based subsidiary. The Fiji-based BAT subsidiary provides maternity and paternity leave to employees. Maternity leave is a requirement under the ERP (2007); however, there is no mandatory requirement for paternity leave. As BAT is a United Kingdom-based MNC operating in Fiji, the company uses UK standards of managing employees (providing paternity leave) while at the same time adhering to the local labour standards (providing maternity leave). Another example is the case of hotels in Fiji. The hotels have to hire 5 per cent of the graduates from the National Employment Centre (NEC) even though the preference of the employers is University of the South Pacific (USP) graduates. The military regime has made it mandatory for all the employers in Fiji that have more than 50 workers to employ attachés from NEC on a ratio of 5 per cent of the total workers employed in the company (Government of the Republic of Fiji, 2009).

Societal factors: The societal factors such as the culture, values, norms, ethics, good governance and societal expectations all have an impact on the HRM practices adopted by organisations. In order to survive in the dynamic environment, most large organisations commit to wider corporate social responsibility to gain public support, an optimistic corporate image and to attract talented employees. For instance, J Hunter Pearls Fiji Ltd employs villagers from the Savusavu community and maintains good relationship with the indigenous people to improve sales and to improve the quality of the products. This company uses a consultative and cooperative approach to deal with sensitive societal issues. Another example is Jacks Fiji Ltd that has become the leader of handicrafts in Fiji by purchasing the handicrafts directly from the villagers. Jacks Fiji Ltd is able to maintain authenticity of the handicrafts while its competitors are unable to. Jacks Fiji Ltd also hires staff that are able to effectively communicate with the village handcrafters. When there is a death in one of the villages, this company takes part in the funeral and financially supports the families of the handcrafters’ (White, 2007).

Characteristics of the workforce: Workforce characteristics such as education level, male to female ratio and ethnic background have an impact on the HRM practices adopted by organisations. In the micro and small businesses, employers usually employ casual workers and focus more on unilateral decision making because the workers are not well educated and aware of their rights in the work-place. For instance, the garment workers are ill-treated because of lack of understanding on the part of the workers about their fundamental rights in the work-place. In the case of medium, large and public sector organisations, the workers are well educated about their rights in the workplace, hence they are empowered and motivated to perform. For example, in the hotels sector of Fiji, the turnover rate of the workers in the cleaning, food and beverage division is usually high and the staff turnover at the front office is very low. Workers in the cleaning, food and beverage division are less motivated to perform as compared to the workers at the front office. The managers in the hotels sector of Fiji rate front office staff as more important than the cleaning, food and beverage staff. As a result of this, the front office staff are highly motivated by the managers to perform and the cleaning, food and beverage staffs are ignored to some extent. This has resulted in higher absenteeism and a higher turnover rate of the cleaning, food and beverage staff as compared to the front office staff (White, 2007).

Competitive intensity: The higher the competitive intensity in the market, the lower the market share and profits, resulting in more rigid HRM practices adopted by organisations. In the case of technical industries, the effect is opposite as organisations try to employ the best workers and grab employees from the competitors to gain sustainable competitive advantage. For instance, Vodafone was enjoying a monopoly in the mobile market in Fiji until recently, that is, before Digicel entered Fiji’s market. The competitive intensity caused both of the organisations to compete for the best technical staff in the market. Similarly, in the hotels sector in Fiji, due to intense competition in the workplace, employers engage in poaching of the senior employees to gain a sustainable competitive advantage over the other hotels. In order to tackle this issue the companies are implementing flexible HRM strategies to retain as many competent employees as possible (White, 2007).

Characteristics of the company: Company characteristics such as type of industry, ethnic background of the owner and size and country of origin of the owner have an impact on HRM practices adopted by organisations in the Fiji islands. As mentioned above, micro and small businesses have poor HRM practices while medium, large and public sector organisations have a proper HRM department with proper implementation of HRM practices. Organisations whose country of origin is a developing country such as China and India usually exploit labour in Fiji (the garment industry) while companies whose country of origin is a developed nation such as the United Kingdom (BAT) and the United States have proper standards for motivating and compensating workers. For example, Ghim Li Fiji was a Chinese-based garment company operating in Fiji. This company used to employ a high volume of female staff and engaged in sweatshop conditions to squeeze the maximum out of the workers (Storey, 2004).

Key Changes in the HRM Function

The HRM function of Fiji is changing and is largely dependent on the organisation’s economic status. As already mentioned above, large organisations in Fiji are focusing on aligning the HRM practices and policies towards the goals, objectives and mission statement of the organisation and moving to SHRM. Unlike the traditional approach, whereby HRM was involved only in recruiting and retaining competent and knowledgeable employees and motivating these employees to perform, the contemporary focus of HRM in Fiji is more strategic in nature. Some of the key aspects of the HRM function that have changed include the following:

Understanding the Individual Needs of the Employees

Under the traditional approach of HRM, the main function of HRM involved understanding the individual needs of the employees and career goals. Currently, the SHRM function involves identifying individual needs and aligning these needs to the profit-maximisation goal of the organisation. For instance, in large organisations in Fiji such as Goodman Fielder, Carpenters Group and Reddy Group, employees are only rewarded if their department is performing well or the company’s overall financial position is improving. In cases when the company is not performing well, employees are motivated to increase their efforts in debt collection and so forth so that they could be rewarded based on their productive efforts (Naidu, 2012b).

Ensure EEO for all Groups Irrespective of Gender, Ethnicity and Race

The traditional approach to HRM involves maintaining balance between the employees from different genders, races and ethnicities. Under the contemporary function of SHRM, organisations are largely focusing on recruiting employees that are competent and can perform the required tasks and at the same time are concerned with maintaining balance with gender, ethnicity and race. For example, at the Fiji Electricity Authority (FEA), in the maintenance and field work section, more males are employed as compared to the females because the nature of the job requires considerable physical effort. To get the maintenance and fieldwork done by the female staff may not be productive for FEA (Naidu, 2011b).

Providing Training and Development for the Employees

The traditional approach to HRM requires organisations to provide training and development for employees. Under the modern SHRM approach, large organisations in Fiji are carrying out proper training needs’ analysis before training is provided to employees. For example, at the Fiji Sugar Corporation (FSC), proper training needs’ analysis is carried out by the training department in conjunction with the HRM department before the training is provided to the employees (Naidu, 2011b). The content of the training is usually aligned with the goals and objectives of the organisation.

Employee Empowerment

Under the traditional approach to HRM, employees are empowered so that they feel a sense of belongingness and accountability towards the organisation. Under the contemporary SHRM approach to HRM, only those employees are empowered in large organisations that are performing and working towards the goals and objectives of the organisation. For instance, at the Australia New Banking Corporations branch in Fiji, the managers that are good advocates and ambassadors of the organisation are empowered to improve the company’s profitability while the trouble makers are punished (through suspension) and non-performers have to work under the strict supervision of the supervisors (Naidu, 2012a).

Effectively and Efficiently Addressing Employee Grievances

The traditional approach to HRM requires efficiently and effectively meeting employee grievances. Under the modern approach to SHRM, employees are required to solve the grievance keeping in mind the organisation’s quality (reputation and image) and profitability. For instance, at the Reddy Group of companies, more specifically at the Tanoa International Hotel, employees have to be nice and humble towards the tourists and the local customer even though the customers may be wrong sometimes (Naidu, 2011b).

Objective Performance Management System

The traditional approach to HRM requires a performance appraisal system to be objective in nature. Under the new SHRM approach to managing employees in Fiji, organisations are ensuring that the performance appraisals are objective and the outcome of the appraisal should be directed towards the goals, mission and objectives of the organisation. For example, at the Reddy Group of Companies, the 360-degree performance appraisal is conducted by a centralised HRM department to ensure the accuracy, reliability and transparency of the appraisal. The HR manager ensures that the outcome of the performance appraisal should increase the company’s profitability.

Key Challenges Facing HRM

The HR managers are finding their role as employee champions and management advocates very demanding. Some of the main challenges facing the HRM include:

Implementing Proper HRM Information Systems in Order to Effectively Manage and Make Informed Decisions

Generally, the implementation of HRM information systems in Fiji is poor. There is no HRM information system in small organisations and in large organisations the HRM information system is implemented with a lack of skilled labour to manage the system. For instance, in small businesses the employees are casually hired, hence the employers do not see a necessity to implement a HRM information system. In large organisations, there is lack of specialised and skilled labour to implement proper HRM information systems (Naidu, 2012a).

Aligning the HRM Practices with the Goals, Objectives and Mission Statements of the Organisation

Aligning the HRM policies and practices to the goals, objectives and mission statements of the organisation is a very challenging task. The HR managers are faced with various difficulties in undertaking this task. For instance, the primary goal of any organisation in Fiji is to maximise its returns to the shareholders but HR managers are faced with difficulties as they have to implement policies that minimise the labour cost and at the same time motivate employees to perform (Chu and Siu, 2001).

Economic, Political and Legal Crisis

Managing human resources in the context of economic, political and legal crises is difficult as these environmental factors are dynamic and are continuously changing. Pressures from the global economic crisis, local and international politics and the legal crisis are imposing challenges on HRM. For instance, the implementation of the Essential National Industries (Employment) Decree 2011 is making managing HR very challenging because this decree has created a labour turmoil and this has largely affected the management of human resources in organisations. The implementation of the Essential National Industries (Employment) Decree 2011 has resulted in labour unrest and trade unions are strategising to take industrial action in conjunction with the international trade unions (Anthony, 2011).

Lack of Financial Budget for Training and Development

Lack of financial budget for training and development is a major issue for micro, small and medium organisations in Fiji. The main aim of the micro, small and medium enterprises is to survive in the dynamic internal and external environment. For instance, according to the majority of the business operators in the tourism sector, survival has become a concern due to a decline in tourist numbers. Currently, the tourism business operators do not have sufficient funds to invest in training and development (Naidu, 2011b).

Lack of Awareness of Employees about their Fundamental Rights at the Workplace

Employees in Fiji lack awareness and knowledge about their fundamental rights in the workplace. This is simply because a large majority of the workforce in Fiji are not well educated. For instance, employees in the garment industry are not well aware of their rights under the ERP (2007). This is the major reason that they are exploited in the workplace (Naidu, 2011b).

The Future of the HRM Function in the Fiji islands

The future of the HRM function in the Fiji islands is unpredictable. The development of the HRM function is closely knitted to the economic, political and legal situation of Fiji. Generally, the development of the HRM function in the Fiji islands can be divided into two functional categories. The first category includes the pessimistic approach to the future development of the HRM function. This approach foresees a worsening of Fiji’s economy. If Fiji’s economy worsens then it could come to a stage that HRM may be eliminated from some sectors of the economy and gets replaced by the traditional methods of managing employees. The following changes will be eminent.

Increase in Labour Unrest and Employee Grievances

If the economy of Fiji contracts then employers will pressure the government to implement labour laws that are employer-friendly so that labour costs could be lowered and the maximum could be squeezed out from the workers. This will result in an increase in labour unrest and employee grievances. For instance, the implementation of the Essential National Industries (Employment) Decree 2011 has resulted in labour unrest and trade unions are strategising to take industrial action in conjunction with the international trade unions (Anthony, 2011).

Elimination of SHRM from some Sectors of the Economy

The SHRM model (Figure 13.1) may be eliminated from the essential industries of Fiji such as the financial industry (Australia and New Zealand Banking Corporation, Bank of Baroda, Bank of South Pacific, Westpac Banking Corporation and Fiji Revenue and Customs Authority), the telecommunications industry (Fiji International Communications Ltd, Telecom Fiji Ltd, Fiji Broadcasting Corporation Ltd), the Civil Aviation Industry (Air Pacific Ltd) and the Public Utilities Industry (Fiji Electricity Authority, Water Authority of Fiji) if the economic, political and legal conditions of Fiji further worsen. These are all the essential industries gazetted by the military government. For instance, the deterioration of the economic, political and legal condition of Fiji will initiate a major reform of the existing labour laws. The new labour laws that will be implemented will deteriorate the employees’ working conditions and rights in the workplace, hence making it impossible for employers to implement the SHRM model (Naidu, 2012b).

Replacement of Strategic Human Resource Management with Personnel Management

If Fiji’s situation further worsens then it is likely that the existing SHRM model (the SHRM model presented in this paper) will be replaced by personnel management. The employment conditions in Fiji may worsen if more employment decrees are implemented that do not have the support of trade unions, donor agencies and THE ILO. As a result of this, there will be a drastic increase in ‘brain drain’. For instance, a large bulk of the educated workforce will migrate to countries such as New Zealand and Australia for greener pastures (Naidu, 2011b).

The second category includes the optimistic approach to the future development of HRM. The following changes will occur in the HRM function if there is a positive outlook for Fiji’s economy.

Investment in Cross-Functional and International HRM

If there is a positive outlook for Fiji, employers will be required to invest in cross-functional HRM in order to gain a sustainable competitive advantage. In future, the business environment will become more complex and dynamic, hence there will be a need for HR managers that are well versed in marketing, operations and finance but not just in HRM. Parallel to the argument of institutional theory, the HR managers will be required to understand the different functions of the organisation so that they are able to effectively and efficiently manage employees from different departments. Organisations will expand, hence there will be a need to invest in international HRM. For example, as Flour Mills of Fiji and Punjas spreads its operations across the Pacific islands, the HR managers of each of these companies have to invest in managing employees from different islands in the Pacific because there is significant variability in culture (Naidu, 2011b; Chu and Siu, 2001).

Computerisation of HR Functions

Organisations will have to spend more resources in computerising HR functions. HR processes have to be computerised in order to achieve efficiency and effectiveness. New software will be developed for managing the different HRM practices. For example, currently Fiji does not have sufficiently talented employees to manage the HR information systems. The tertiary institutions are not providing specialised courses on HR information systems. All these factors will create challenges for managing HR information systems and organisations will have to implement strategies to counter these challenges (Naidu, 2011b).

Case 1: Paradise Manufacturers Fiji Limited (PMFL)1

Paradise Manufacturers Fiji Limited (PMFL) is a tobacco manufacturing United Kingdom-based MNC that started its operations in the Fiji islands in 1951. The PMFL has 45 cigarette companies in 39 countries worldwide. This company’s vision is to establish higher standards of leadership in Fiji’s tobacco industry under the guiding principles of strength, diversity, open-mindedness, freedom through responsibility, and enterprising spirit. On the packet of every cigarette that is sold in Fiji there is clear indication of the average level of nicotine and tar that each cigarette will deliver. The PMFL is affected by high taxation and stringent regulation of the tobacco market. Serious health warnings on tobacco packets, smoking being restricted in public places, and a ban on advertising of tobacco-related products are some of the issues that PMFL has to deal with.

On the HRM side, the Occupational Health and Safety of the employees is a primary concern to the company. There are stringent guidelines and notices placed in the manufacturing area regarding employee safety. One of the most important HRM policies of this company is that employees have their safety gear on while they are in the manufacturing area. Employees who do not adhere to this policy have to face stringent penalties. For instance, workers that do not have safety equipment on while on site have to face the disciplinary committee who decide on the penalty for the crime committed by the employee. The HRM policies on fundamental principles and rights at work; employment relations advisory board; appointments, powers and duties of officers; contracts of service; protection of wages; holidays and leave; hours of work; equal employment opportunities; children; maternity leave; redundancy for economic, technological or structural reasons; employment grievances; registration of trade unions; rights and liabilities of trade unions; collective bargaining; employment disputes; strikes and lockouts; protection of essential services, life and property; institutions and offences are all guided by the Employment Relations Promulgation (2007) and the Essential National Industries (Employment) Decree 2011. The PMFL uses its own discretion in managing labour employed from other countries. This company also gives priority to team work, employee empowerment and quality circles to improve the quality of the products. The PMFL workers are unionised and dispute resolution machinery is effectively set out in the collective bargaining agreement. This company is trying its level best to effectively manage employees in the light of the economic downturn that it is currently facing. Some of the factors that have shaped the HRM practices adopted by the PMFL include economic factors, political factors, societal factors, the characteristics of the workforce, competitive intensity and the characteristics of the company. Currently, the global economic pressures from the Italy debt crisis and the political instability of Fiji are having considerable impact on the earnings of the PMFL.

Primarily, the workers employed by the PMFL can be divided into two categories. The first category consists of those who are highly educated and skilled. These workers are the core employees of the organisation and they are motivated for best performance. The second group of workers are from the uneducated category. As PMFL is an MNC with cohesive and internationally recognised labour practices, the company treats the uneducated group of workers as being as important as the educated group of workers. This company also believes that profits could be improved if synergy could be achieved between both groups of workers.

Recently, many changes have occurred in the HRM function of PMFL. In particular, the implementation of the Essential National Industries (Employment) Decree 2011 has resulted in key mandatory changes to the HRM policies and practices. Some of these changes include re-registering of the existing registered trade unions under the Employment Relations Promulgation (2007), replacement of all existing collective bargaining agreements and suspension of the majority of trade union activities such as job actions, strikes, slowdowns and any form of financially harmful activity. These new clauses of the Essential National Industries (Employment) Decree 2011 make it obligatory for PMFL to change the collective bargaining and grievance handling function of the HRM.

According to the HR manager, the contemporary legal, political and economic pressures are making the task of managing employees in the PMFL very challenging. The HR manager also indicated in his interview that the future of HRM at the PMFL is very strong for the employees. Employees are the key asset to the company and managing employees effectively and efficiently is one of the priority concerns for PMFL.

Discussion Questions

- Why is Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) a primary concern for the PMFL? Explain with examples.

- Describe the employee management model practiced by PMFL. Explain with examples.

- Explain some of the factors that are affecting the HRM function of PMFL.

- Explain the impact of the newly implemented Essential National Industries (Employment) Decree 2011 on the employee management practices at PMFL.

- Why is managing employees a challenging task for PMFL?

Conclusion

This chapter has discussed the HRM environment in the Fiji islands. The first section of this chapter outlined the historical development of personnel management, industrial relations, employment relations, HRM and SHRM in the Fiji islands. The second section of this chapter outlined the role of the state, trade unions, employer association, non-government organisations (NGOs), donor agencies and trading partners in the HRM environment. The third section outlined the endogenous and exogenous environmental factors that affect HRM practices. The fourth section discussed the key changes in the HRM function. The fifth section examined the key challenges and the future of HRM in the Fiji islands. The final section provides the case study of PMFL.

Useful websites

www.usp.ac.fj/editorial/jpacs_new/Snell.PDF

https://ojs.lib.byu.edu/spc/index.php/PacificStudies/article/viewFile/9853/9502

www.asu.asn.au/media/all-airlines-bulletin14-110919-factsheet.pdf

www.fijitimes.com/story.aspx?id=175648

www.fijitimes.com/story.aspx?id=175648

www.stuff.co.nz/world/south-pacific/5621934/Top-NZ-lawyer-criticises-Fijis-suppression

www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/lang--en/index.htm

www.ilo.org/public/english/bureau/program/dwcp/download/fiji.pdf

http://news.smh.com.au/breaking-news-world/new-fiji-decree-hits-unions-20110809–1ikja.html

Note

1. This is a pseudonym and not the real name. The real identity of the company is not revealed as this was one of the conditions attached by the company when permission was granted to study the HRM practices.

References

Anthony, F. (2011) Regime Enforces Repressive Decree, Fiji Trades Union Congress. Fiji Islands: Des Vouex Road Suva.

Australian Council of Trade Unions (2011) Union Condemn Fiji’s Continued Attack on Work Rights, Press Release, 12 September. Australia: ACTU.

Baljekal, R. (2010) Building Human Capital: A strategic perspective, Leaders’ Forum, 29 March, Statham Campus. Fiji: University of the South Pacific.

Budhwar, P. S. and Debrah, Y. (2001) ‘Rethinking comparative and cross national human resource management research’, The International Human Resource Management Journal 12(3): 497–515.

Budhwar, P. S., and Sparrow, P. R. (2002) ‘An integrative framework for understanding cross national human resource management practices’, The International Human Resource Management Journal 12(3): 377–403.

Chand, A. (2011) Global Supply Chains in the South Pacific Region: A study of Fiji’s garment industry. New York: Nova Science Publishers.

Chand, A., and Naidu, S. (2010) ‘The Role of the state and Fiji Council of Social Services in service delivery in Fiji’, International NGO Journal 5(8): 185–193.

Chaudhary, F. (2011) ‘Threat worry’, Fiji Times, 21 July, p. 1.

Chu, P., and Siu, W. (2001) ‘Coping with the Asian economic crisis: The right sizing strategies for the small and medium sized enterprises’, The International Journal of Human Resource Management 12(5): 845–858.

Commonwealth Secretariat (2009) Small States: Economic review and basic statistics. London: Commonwealth Secretariats Publication House.

Elek, A., Hill, H. and Tabor, S. R. (1993) ‘Liberalisation and diversification in a small island economy: Fiji since 1987 coups’, World Development, 21(5): 749–769.

Fiji Employers and Commerce Association (2011) Fiji Employers Federation Research Report, Press Release, 25 October. Fiji: FEF.

Gillion, K. L. (1962) Fiji’s Indian Migrants: A history to the end of indenture in 1920. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

Ministry of Labour Fiji (2011) Essential National Industries (Employment) Decree. Government Printers: Fiji Islands.

Government of the Republic of Fiji (2009) National Employment Centre Decree: 2009. Suva. Fiji Islands.

ILO (2010) Decent Work Country Programme: Fiji. Switzerland: Geneva.

ILO (2012) About the ILO. Switzerland: Geneva.

Irvine, H. J. (2004) Sweet and Sour: Harbouring for South Sea islanders labour at the North Queensland Sugar Mill in the 1800’s, Working Paper, Faculty of Commerce. Australia: University of Wollongong.

Leckie, J. (2003) ‘Trade union rights, legitimacy, and politics under Fiji’s post coup interim administration’, The Journal of Pacific Studies 16(3): 87–113.

Naidu, S. (2011a) ‘Economic challenges imposed by employment relations promulgation (2007) on the private sector of Fiji’, Asia Pacific Journal of Research in Business Management 2(11): 82–98.

Naidu, S. (2011b) Employers Awareness on the Employment Relations Promulgation (2007): Challenges for contemporary and future employment relations. Germany: Lambert Academic Publishing.

Naidu, S. (2012a) ‘The economic impact index of the employment relations Promulgation (2007) on the Fiji Islands’, International Journal of Business Growth and Competition 2(2): 152–164.

Naidu, S. (2012b) ‘The nexus between human resource management practices and employment law in the Fiji Islands: A study of the employment relations promulgation’, International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business (in press).

Naidu, S., and Chand, A. (2012) ‘A comparative study of the financial obstacles faced by the micro, small and medium enterprises in the manufacturing sector of Fiji and Tonga’, International Journal of Emerging Markets 7(3) (in press).

Naidu, V. (2004) Violence of Indenture in Fiji. Fiji Islands: Institute of Applied Science.

Pacific Islands Forum (PIF) (2009) 2009 Statement to Pacific Island Forum Trade Ministers Regarding Deliberations on Potential PACER-Plus Negotiations. Suva: Fiji Islands.

Pathak, R. D., Budhwar, P. S., Singh, V. and Hannas, P. (2005) ‘Best HRM practices and employees’ psychological outcomes: A study of shipping companies in Cyprus’, South Asian Journal of Management 12(4): 7–24.

Pathak, R. D., Chauhan, V. S., Dhar, U. and Gramberg, B. V. (2009) ‘Managerial effectiveness as a function of culture and tolerance of ambiguity: A cross cultural study of India and Fiji’, International Employment Relations Review 15(1): 74–90.

Prasad, S., Hince, K., and Snell, D. (2002) Employment and Industrial Relations in the South Pacific: Samoa, the Cook Islands, Kiribati, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Fiji Islands. Australia: McGraw-Hill.

Reddy, S. (2010) The Future of Fiji’s Economy, Presentation to the Fiji Institute of Accountants. Fiji Islands: Suva.

Schuler, R. S., and Jackson, S. E. (2007) Strategic Human Resource Management, 2nd edn. USA: Blackwell Publishing.

Snell, D. (2000) ‘Globalisation and workplace reforms in two regional agri-Food industries: Australian meat processing and Fiji’s sugar mills’, The Journal of Pacific Studies 24(1): 51–76.

Storey, D. (2004) The Fiji Garment Industry. Oxfam. New Zealand.

Sziraczki, G., Huynh, P. and Kapsos, S. (2009) The Global Economic Crisis: Labour market impacts and policies for recovery in Asia, ILO Asia Pacific Working Paper. Switzerland: Geneva.

White, C. M. (2007) ‘More authentic than thou: Authenticity and othering in Fiji tourism discourse’, Tourism Studies 7(1): 25–49.