INTRODUCTION

The regulations tell companies what they must do, but they don't say how to do it. In short, they are prescriptive, not descriptive. The regulations all call for procedures, so companies are compelled to have them in place. Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) show how companies apply what the regulations say to their specific operations. As such, they must be clear, they must be true, and they must work together. SOPs also reflect good business because they are safeguards for ensuring that processes and activities occur as they should, so that they yield the same results every time. Surely then, having sound procedures in place makes for good compliance; moreover, and perhaps equally important, they help keep companies on track and functioning optimally. This chapter addresses the procedural infrastructures that companies must have. It answers the following questions:

- Why is there so much emphasis on SOPs and where can we find the requirements?

- How binding are SOPs for our company?

- How can we determine which SOPs we need?

- How many SOPs should a company have?

- At what point do we need to put SOPs in place?

- If we follow the regulations, and do quality assurance audits, will we be compliant?

- What are global SOPs?

- What are quality manuals, and why do companies have them?

- What's the difference between a work instruction, an SOP, and a policy?

- Do work aides, which are documents that help interpret our SOPs, need controls?

- Is it a good practice to maintain SOPs and IOPs?

- Is it acceptable to have SOPs but not to follow them?

- If our equipment already has a manual that tells how to use it, why should we write an SOP?

- Must we have an SOP on SOPs?

- Should every area of a company have its own physical set of SOPs?

- How do we prevent duplicate or overlapping SOPs?

- Shouldn't an SOP be a perfect document before it's put in place?

- Is it a good practice to post our SOPs to our company's intranet so that anyone can access them?

- If we are rolling out a new process that has four phases, and we have only implemented phase 1, can we write an SOP to cover all four phases that will eventually be in place?

- Since we have a multicultural, global workforce, should our SOPs all be in English, as the universal business language?

- Can a form serve as an SOP?

- Can we deviate from our SOPs?

- Is it okay to have pilot SOPs that only a few people follow, so that we can test the procedure?

- How should we control reference documents that are instructional?

- Does a sponsor need SOPs in place if CROs are managing clinical activities?

- If a CRO relies on our SOPs, is it necessary that a CRO has its own SOPs?

- What's the best way to control procedures?

- Why do companies follow a document control process?

- What's the difference between superseding and obsoleting an SOP?

- What do we do if we want to permanently obsolete an SOP and it's cross-referenced in other SOPs?

- Can we make our SOPs effective on the day they are signed off?

- How much time should we allow between approval of an SOP and issuing an effective date?

- Can we get rid of training forms if we scan them into our document management system?

- How often do SOPs require review?

- Does the FDA expect us to keep comments on SOPs that were generated during the review process?

- How can you paginate attachments to SOPs?

- Should forms be contained within SOPs?

- How can we link who completed an electronic form to the form itself?

- Is it okay to annotate a working copy of an SOP to reflect an improvement until we can get the new version through the system?

- What should we do when we recognize the need for a new procedure and need it faster than our system permits?

- How do you handle the situation where there is a new procedure that doesn't reflect what we actually do?

- If you make changes to an SOP, do you need to look at any other documents?

- Should the version number change when an SOP undergoes review and there are no changes to it?

- How can we know what changes we've made to SOPs in sum since the first version?

- Should SOPs have a table of contents?

- How long should SOPs be?

- What happens if we identify a need for an SOP and then decide we don't need it?

- Can I revise an SOP from the copy I have on my workstation, since I am the author?

- If a person who has authored SOPs leaves a company, what happens to those documents in the next review cycle?

- Do the regulators define any specific format for SOPs?

- What are the conventions for SOP formats?

- Should we simply put N/A if an element in an SOP doesn't apply?

- Is it good to use a template that has a series of tables with item and action?

- Should we update an SOP if we find a spelling or mechanical error?

- What documentation practices should SOPs cover?

- What SOPs do we need for our document and record-keeping systems?

- What SOPs should you have to support document and record-keeping systems?

- Must we include training requirements in every SOP?

- What happens if people undergo training, but fail to follow a procedure?

1. Why Is There So Much Emphasis on SOPs and Where Can We Find the Requirements?

Written procedures are a requirement of all the regulations that drive the therapeutic product industry. The International Organization for Standardisation (ISO) sums it up well: “Say what you do, and do what you say” (1). The predicate rules in the United States Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) all call for procedures, as do the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) guidelines (2) and the regulations for most companies involved in developing, manufacturing, or distributing products in the health-care industry.

2. How Binding Are SOPs for Our Company?

If you put an SOP in place, you must adhere to it. SOPs are legally binding for the company. They are based on the requirements in all the binding regulations for therapeutic products that say there “shall be procedures.” The Office of the Inspector General also gives this message: “Procedures are really the law for the company. Companies are very tightly bound by their procedures, which are required to be established. By regulation, such procedures must be written, trained to, followed, documented, and supervised in execution. They must be approved by the quality unit of a company. The agency (FDA) holds a company accountable for this compliance” (3).

3. How Can We Determine Which SOPs We Need?

There is no magic formula. SOPs must reflect what you do relative to your company. In sum, procedural documents form the backbone of the operation, whether you are in preclinical, clinical, manufacturing, distribution, or tracking products in the marketplace. If you are a contractor providing services along this continuum, you are also subject to the regulations that call for SOPs. These documents tell “how it happens here” (4).

4. How Many SOPs Should a Company Have?

There is no correct answer, because each company should have SOPs that address all areas of their business. SOPs, work instructions, and other informative documents work together to promote a uniform working platform and provide a basis for consistent training.

5. At What Point Do We Need to Put SOPs in Place?

It depends on your level of comfort with risk. SOPs provide the basis for doing work in a uniform manner. If your work is not uniform, how good are the results? If you are doing straight research, procedures are not a requirement, except for those that support chemical hygiene, and safety, and companies typically put documents in place for compliance with 29 CRF 1910. However, once you have proof of concept, it's time to start thinking about standardizing what you do. Good controls actually help the business function, they help ensure that your development activities will be compliant, and thus they support your product from early development and beyond.

6. If We Follow the Regulations and Do Quality Assurance Audits, Will We Be Compliant?

You must follow the regulations, to be sure. But while the regulations tell you what you must do; they don't tell you how to do it. Furthermore, they are explicit in calling for written procedures that are followed. Even though you may follow the regulations, you must have SOPs that explain how you do so. The Office of the Inspector General issued a guidance on Developing a Compliance Program for Pharmaceutical Manufacturers which called for these elements for an effective compliance program:

- Implementing written policies and procedures

- Designating a compliance officer and compliance committee

- Conducting effective training and education

- Developing effective lines of communication

- Conducting internal monitoring and auditing

- Enforcing standards through well-publicized disciplinary guidelines

- Responding promptly to detected problems and undertaking corrective action

Note that the very first item is written policies and procedures. The additional elements, in turn, should be reflected in written policies and procedures (5).

7. What Are Global SOPs?

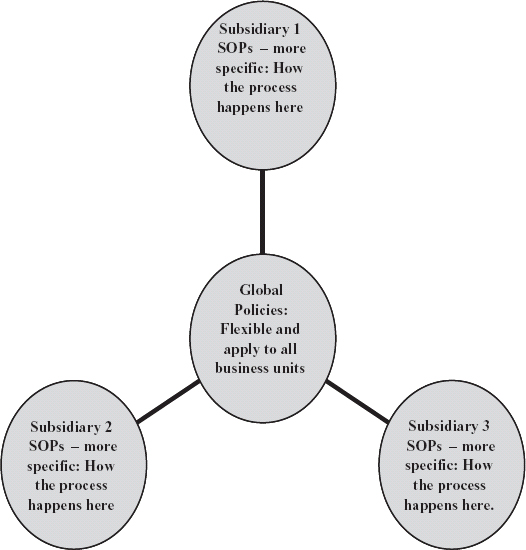

These are documents that address the big picture. Often a parent company will issue global SOPs to its sites, and the sites will then, in turn, create SOPs that define how things happen there. (See Figure 7.1.) Another way to look at the structure of the SOP system is as a pyramid: The top-level or global documents give the “big picture,” and SOPs show the backbone of what actually happens across the company, while work instructions tell how to perform specific tasks that have defined start and stop points and one or two people can carry them out.

8. What Are Quality Manuals, and Why Do Companies Have Them?

Quality manuals are comprehensive, big picture documents that show how quality drives the operations, from the CEO down. They tell what regulations a company adheres to, and they indicate how quality is communicated throughout the company. They address quality records as well. They are required for device companies and companies adhering to ISO standards. Right now there is no dictate that pharmaceutical companies put them in place, but that may change as GMPs evolve. Required or not, many pharmaceutical and biotech companies have quality manuals because they make sense, particularly if the companies supply product or services to a client base.

9. What's the Difference Between a Work Instruction, an SOP, and a Policy?

Companies often make distinctions as to document types. Typically, a policy is a top-level document that describes what is to be done but now how it is to be done. An SOP is a high-level document that describes how a process occurs. A work instruction provides details that describe a process in detail, typically with defined start and stop points. Regardless of what a company calls its documents, they require tight controls.

Figure 7.1. Organization of SOPs for multiple sites.

10. Do Work Aides, which Are Documents that Help Interpret Our SOPs, Need Controls?

Yes, any “how to” document that gives instructions needs to be controlled. “How to” documents include work instructions, instructions, global policies, franchise documents, and more. It doesn't matter what you call them; they are subject to the same processes as your formal SOPs.

11. Is It a Good Practice to Maintain SOPs and IOPs?

Some companies maintain two sets of procedures: Standard Operating Procedures and Internal Operating Procedures. The difference is that SOPs are what are made available during inspections and audits, and IOPs reflect what is actually done in more detail. There's no need to cover the same processes in two sets of documents, however. A danger is that you will update one document, but fail to adjust its coordinate document. Auditors may and often will ask to review both SOP and IOPs because all instruction documents are relevant to the processes under inspection. Such redundancy also implies that the company does not want to reveal what it actually does, and that is a red flag for investigators.

12. Is It Acceptable to Have SOPs but Not to Follow Them?

No. If a procedure is in place, regardless of whether the regulations call for it, it is binding, and you must follow it. If you have procedures that are superfluous, the best thing to do is retire them and create SOPs that you want to follow because it makes good business sense.

13. If Our Equipment Already Has a Manual that Tells How to Use It, Why Should We Write an SOP?

The regulations for all therapeutic products are specific in requiring that companies have SOPs that tell how activities occur, so companies need to comply with the law. But more importantly, SOPs make sense. A manual may cover more than your process calls for; it will not detail scope and responsibilities as they apply to your company; and you have no guarantee that the manual will stay current with your actual practices.

14. Must We Have an SOP on SOPs?

Some industry experts believe that all companies should have an SOP on SOPs, a document that explains the system for creating, reviewing, approval, and controlling SOPs. But there is no specific dictate for such a document. What is more important is that SOPs cover all facets of documentation, so a company may have a document management SOP that includes SOPs. This model is particularly effective when there is an e-system in place and all documents are contained within it.

15. Should Every Area of a Company Have Its Own Physical Set of SOPs?

It's not necessary today with hybrid and fully electronic systems. It used to be convenient to have a full manual of SOPs for each area when systems were purely paper-based. Now, because electronics have made controlled accessibility possible, all areas of a company can adhere to common SOPs. Since it's unlikely that every SOP will apply to every area, SOPs can tell where a procedure applies in the Scope section. Such an approach to procedures prevents overlaps where more than one SOP addresses the same process. In the past, such a practice has proved to be troublesome, since through the revision process such replicate SOPs often become modified and eventually may be significantly different and even contradictory.

16. How Do We Prevent Duplicate or Overlapping SOPs?

The key to ensuring that SOPs do not duplicate information is to have each SOP address a process or a part of a process. SOPs must also identify where the SOP applies. Furthermore, if an area of a company determines that it needs an SOP to cover a certain process, the first thing to do is search the system to see if there is an SOP that covers related information that can be modified to incorporate the new information and the scope of application.

17. Shouldn't an SOP Be a Perfect Document Before It's Put in Place?

It's better to put an SOP in place even if you don't think it's 100% perfect. An SOP in place is better than a planned SOP, and a planned SOP is better than no concept of an SOP. Putting an SOP in place lets you perform the process in real time, and you'll see what needs correcting pretty quickly. As soon as you do, you can put it into review for revision, while you still have the original in place. The next version will be better. That's the process of SOPs—they are really organic documents that grow and change as the company's processes do. With that said, you should not put an SOP in place that you know is incorrect. It is one thing to lack detail, but is quite another to provide incorrect information.

18. Is It a Good Practice to Post Our SOPs to Our Company's Intranet So that Anyone Can Access Them?

It can be if you exercise some controls. Posted documents must be exact replicas of the official document, and they must be posted in a form that doesn't allow for alteration of the document (read only). It they are printed, it's possible to include a time and date stamp with the words “Valid only on print date.” It's never a good idea to have uncontrolled copies of SOPs because you run the risk of people not following the correct SOP, and that is definitely something that inspectors look for.

19. If We Are Rolling Out a New Process that Has Four Phases, and We Have Only Implemented Phase 1, Can We Write an SOP to Cover All Four Phases that Will Eventually Be in Place?

No SOP should be approved and made effective if the process has not been verified or the users of the SOP cannot perform the procedure. It is better to issue an SOP for the current phase and then update it as the subsequent phases roll out.

20. Since We Have a Multicultural, Global Workforce, Should Our SOPs All Be in English, as the Universal Business Language?

This is a matter of quality. Which language will best ensure compliance with the SOPs? SOPs need to be in the language that the users understand.

21. Can a Form Serve as an SOP?

Many companies are moving toward this model, where forms are instructional. Such companies build directions into the forms themselves, so that the forms become the documentation for the procedure. It's important that the procedures themselves be identified in a master list or log, and that training on the forms is the same as for any other procedure.

22. Can We Deviate from Our SOPs?

Deviations are either planned or unplanned. A company may have a special project that requires a somewhat different process than the SOP in place specifies. In such an instance, for the special project, the company can write a planned deviation in advance of the project. Deviations that are unplanned—say a failure to do a QA check on gowning—require documentation of the deviation, investigation, and resolution of the outcome.

23. Is It Okay to Have Pilot SOPs that Only a Few People follow, So that We Can Test the Procedure?

Yes, provided that your SOP on SOPs explains how the pilot SOP system works. A company can approve a pilot SOP and train a limited number of operators to test the new process. The existing, effective SOP remains in place, and the rest of the workforce follows it until the pilot either becomes effective and supersedes it or there is a decision not to implement the pilot process.

24. How Should We Control Reference Documents that Are Instructional?

Reference documents can provide important information. But if they are not binding, you can say so, much the way that the FDA does in its guidance documents. In short, your formal procedures are binding; reference documents do not have to be. Reference documents are a good place to put information that is nice to have, but does not affect the outcome of a process. For instance, preferences for speaking about products can go into a reference document such as a style guide. As another example, if you say “put one space between sentences” in an SOP, you make the directive binding, and that's just silly. Such information is best reserved for reference documents.

25. Does a Sponsor Need SOPs in Place If CROs Are Managing Clinical Activities?

Yes. While there is no requirement in the regulations, guidance documents clearly establish this expectation. But if you think about it, a sponsor needs to ensure that its products, in any phase of testing, are subject to correct controls so that the outcome is valid. A sponsor can rely on a CRO's SOPs, but only if the SOPs are approved equivalents of the sponsor's own procedures.

26. If a CRO Relies on Our SOPs, Is It Necessary that a CRO Has Its Own SOPs?

Yes. As a service organization, a CRO must be compliant with the regulations that govern its activities. The regulations for this industry require SOPs.

27. What's the Best Way to Control Procedures?

Procedures are documents that have a life cycle that includes review and reversioning. Before anyone writes a procedure, there should be a search of a log or electronic system to make sure that no one else is writing a similar document, or that the new document will be redundant or contradictory to one that's already in place. For revisions, the search should provide evidence that no one else is currently revising the document. So the first step is approval of the concept for creating a new or revising an existing document. A new document is drafted in a blank template, and a revision is to a controlled copy of the electronic file of the previous version. Review by designated reviewers and revision are part of the cycle. When there is concurrence, designated approvers sign off, and the document history log gets updated. Next there should be a training period, followed by release of the new document or new version of a document. Finally, the document is issued as “effective,” and any previous versions are archived.

28. Why Do Companies Follow a Document Control Process?

The regulations are quite clear on what has to happen. Even though a company may not be a “manufacturer,” the standards for products, regardless of the stage of development, need to be consistent. Here's what the regulations say:

Sec. 820. 40: Document Controls.

Each manufacturer shall establish and maintain procedures to control all documents that are required by this part. The procedures shall provide for the following:

(a) Document Approval and Distribution. Each manufacturer shall designate an individual(s) to review for adequacy and approve prior to issuance all documents established to meet the requirements of this part. The approval, including the date and signature of the individual(s) approving the document, shall be documented. Documents established to meet the requirements of this part shall be available at all locations for which they are designated, used, or otherwise necessary, and all obsolete documents shall be promptly removed from all points of use or otherwise prevented from unintended use.

(b) Document Changes. Changes to documents shall be reviewed and approved by an individual(s) in the same function or organization that performed the original review and approval, unless specifically designated otherwise. Approved changes shall be communicated to the appropriate personnel in a timely manner. Each manufacturer shall maintain records of changes to documents. Change records shall include a description of the change, identification of the affected documents, the signature of the approving individual(s), the approval date, and when the change becomes effective (6).

29. What's the Difference Between Superseding and Obsoleting an SOP?

Supersede usually mean that a new version of the document is effective and the previous version is no longer effective. Obsolete usually means that no new version of the document will be made and the current version is no longer effective.

30. What Do We Do If We Want to Permanently Obsolete an SOP and It's Cross-Referenced in Other SOPs?

Before an SOP can be made obsolete, all SOPs that reference it must be updated to remove the reference. The history of the obsolete document must also indicate why it is no longer active.

31. Can We Make Our SOPs Effective on the Day They Are Signed Off?

It's not the best practice. There must be sufficient time to make sure everyone impacted by a new or revised SOP knows about it and undergoes training as appropriate.

32. How Much Time Should We Allow Between Approval of an SOP and Issuing an Effective Date?

It depends on how quickly you can train the people who will use the SOP. You may be able to train the users the same day the SOP is made effective, or it may take a week or more. The key is to train the users before they use the SOP. This doesn't that mean all users of the SOP have to be trained by the effective date.

33. Can We Get Rid of Training Forms If We Scan them into Our Document Management System?

As with all paper records, once they are scanned to make electronic records and those records are backed up, the paper record can be destroyed. Most companies keep paper records for a short time period such as when they are actively being accessed or are subject to audit. Most companies also realize the cost savings associated with only keeping electronic records and destroy paper records at regular intervals.

34. How Often Do SOPs Require Review?

The regulations call for “periodic review.” Industry in the United States has determined that a 2-year cycle is appropriate for SOPs, but some companies adhere to a yearly or 18-month cycle. In some countries, an initial SOP is reviewed after one year, and then the SOP goes into a 3-year cycle. More important, SOPs require review any time the processes that they control are modified.

35. Does FDA Expect Us to Keep Comments on SOPs that Were Generated During the Review Process?

No. The regulations are clear in the requirement for review, and accordingly you must show that there is a review component to your SOP system. If you have an e-system, the review process is documented in the metadata. Some companies export a document for review, and they route a paper copy with a signature form. Others make a PDF copy and route it through the company's intranet, so reviewers can post comments. Either way, based on the review comments, the SOP draft changes until there is concurrence and a version that is approvable. The final version then receives approval. You don't need to keep reviewer's comments.

36. How Can You Paginate Attachments to SOPs?

This is a matter of preference and precedent. Most documents are created from MS Word. You can either continue numbering or restart numbering for the attachment. In some cases, such as a single page form, you may not want a page number on an attachment. As long as the SOP identifies the attachment and it is clear where the attachment begins and ends, you are free to paginate as you like.

37. Should Forms Be Contained Within SOPs?

Whether forms should be included in SOPs is a matter of opinion. Forms should have a unique document number and version number and should be controlled, and SOPs should reference those used in a process. Forms typically undergo revision faster than SOPs do. That's one reason companies keep forms separate, because revising the form could mean revising the SOP. Some companies that do handle forms this way state that “Revision to the form does not require revision to the SOP.” If a form is in an SOP, then the SOP and form have to be updated together. If a form is separate from the SOP, care must be taken to update the SOP if updates to the form impact the instructions. In no cases should a form be in an SOP and also be separate.

38. How Can We Link Who Completed an Electronic Form to the Form Itself?

Depending on the electronic form used, you may be able to capture the user logged on to the operating system. You may have to prompt the user to enter their name or other identifier. Some forms are part of computer systems that require the user to log in, so the user is automatically captured.

39. Is It Okay to Annotate a Working Copy of an SOP to Reflect an Improvement Until We Can Get the New Version Through the System?

It's best not to. SOPs are binding for companies, and annotations violate the process for review and approval of changes. An option is to prioritize the review process for a new version, so that it goes through your system more quickly. If you violate your process for SOP generation, review, and approval in the process, however, it is a deviation, and you must document it.

40. What Should We Do When We Recognize the Need for a New Procedure and Need It Faster than Our System Permits?

This is a deviation from your standard SOP on SOPs, and you must document the deviation. Make sure all the appropriate people have buy in for the new procedure, then write, approve, train, and implement as quickly as possible.

41. How Do You Handle the Situation Where There Is a New Procedure that Doesn't Reflect What We Actually Do?

Suppose your boss pushes an SOP through the system for a process that you are not aware of, and then tells you to train your staff, but it's not workable for what you actually do. Several issues are at play here. If you have a procedure for generating an SOP, has the boss followed it? If so, why don't you know about it in advance? You may have a faulty SOP on SOPs because impacted areas need to know about planned procedures and ideally participate in the generation and review. You can then suggest revisiting the SOP on SOPs. But your problem may reflect personnel issues if the boss believes that he or she is immune from adhering to established procedures. In such a case, you may need to enlist (tactfully) the assistance of your QA group to stress that failure to adhere to standard procedures poses a compliance risk to the company.

42. If You Make Changes to an SOP, Do You Need to Look at Any Other Documents?

Yes. Any documents referenced or affected by an SOP should be considered when making changes to an SOP. These include forms, templates, or other documents that are part of the process related to the SOP being updated. Documents rarely stand alone. For instance, a quality manual may talk about quality in general terms, but an SOP may give an overview of calibration within the company. A next-level document might be instructions for calibrating specific equipment, such as a scale. A calibration sticker is also part of the documentation.

43. Should the Version Number Change When an SOP Undergoes Review and There Are No Changes to It?

Companies do not need to change a version number if no changes are made to the SOP. The review is recorded in the document's history. Not changing the version ensures that the training records always link to the correct document. That said, changing the version number for every review cycle is optional, and many companies build that feature into their systems to verify regular review cycles. Regardless, the SOP that addresses the handling of SOPs must tell how the company handles reversioning and training.

44. How Can We Know What Changes We've Made to SOPs in Sum Since the First Version?

SOPs should contain a version history that details the types of changes made to each version. This document history is a roadmap that shows the evolution of the procedure.

45. Should SOPs Have a Table of Contents?

Typically, SOPs have standard sections and therefore a table of contents is not necessary.

46. How Long Should SOPs Be?

SOPs should be a short as possible. Most companies prefer to have SOPs that are less than 10 pages; but outside the United States longer SOPs are common. It's best to remember, however, that SOPs are working documents, not manuals.

47. What Happens If We Identify a Need for an SOP and Then Decide We Don't Need It?

Once an SOP has been assigned a document number, that number may not be reused. The number and title and status remain in the log as a history of what you actually planned but then decided against. Your log should also explain the decision not to issue an SOP to justify why you identified an SOP but have no actual document.

48. Can I Revise an SOP from the Copy I Have on My Workstation, Since I Am the Author?

Doing so is a weak practice on two counts. One, the document is an electronic file, even if you maintain an official paper copy; and as such, it requires Part 11 controls as they apply. The secure electronic file is the one that should be released for revision. Two, the copy you have on your workstation may not reflect every change that was made to the document before approval. For instance, does your system allow for mechanical changes such as for typos or spacing? Such changes may have been made to the official previous version, and you may not have them in your version, and are thus not revising the actual document in place.

49. If a Person Who Has Authored SOPs Leaves a Company, What Happens to Those Documents in the Next Review Cycle?

Documents should not be owned and authored by a single person. SOPs describe a process, and maintenance of the SOP is the responsibility of all people that are affected by the document. When a document has to be reviewed, the people with the most process experience participate in the revision process.

50. Do the Regulators Define Any Specific Format for SOPs?

No. But while procedures may look somewhat different from company to company, they mostly adhere to the same conventions.

51. What Are the Conventions for SOP Formats?

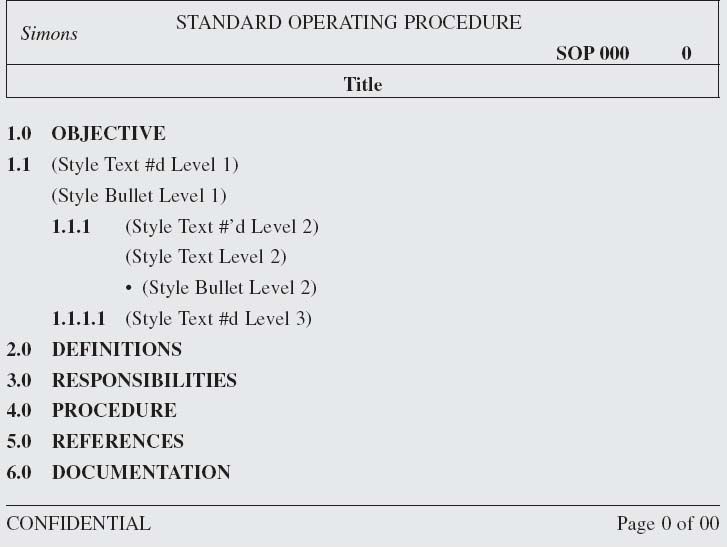

SOPs have headers and footers that identify the type of document, the title, the document ID or number and version, pagination, and, for hybrid systems, an effective date. Common elements such as the following are arrangement with military numbering (1.1, 1.1.1, 1.1.1).

Objective or Purpose

Scope

Acronyms and Definitions

Materials and Equipment

Responsibilities

References/Related Documents

Procedure

Warnings, Cautions, and Notes

Documentation

Appendices

Approvals (for paper and hybrid systems)

Distribution (for paper and hybrid systems)

(See Box 7.1.) Each company must choose the elements their SOPs need. Small companies may have as few as three elements, while a larger organization may have eight or more elements.

52. Should We Simply Put N/A If an Element in an SOP Doesn't Apply?

Many companies do that, since not every procedure calls for materials and equipment, for example. Other companies create templates that are more flexible, so that if a section doesn't apply to a certain process, an author can remove it. Once deleted, the template numbering adjusts accordingly. In such a system, not every SOP has identical elements, but rather elements that are appropriate to the type of process the documents addresses.

53. Is It Good to Use a Template that Has a Series of Tables with Item and Action?

SOPs that use tables for each section are based on information mapping. A strong argument for this sort of organization is that it may be easier to read. Information mapping, however, requires a lot more paper if documents are printed.

54. Should We Update an SOP If We Find a Spelling or Mechanical Error?

There's no need to reversion an SOP for a minor error that has no bearing on the content. Some companies keep a log of changes that they will make to SOPs in the next review cycle. Such a log is a place to record document imperfections—such as a numbering gap or inaccurate punctuation mark that wasn't caught in the last review cycle. It's a vehicle that helps ensure that the review cycle will catch and repair these minor issues. The SOP on SOPs or document management should address this practice.

55. What Documentation Practices Should SOPs Cover?

SOPs should drive all documentation practices. So if a company prepares GLP study reports, for instance, an SOP should delineate the “how to” for that document type.

56. What SOPs Do We Need for Our Document and Record-Keeping Systems?

Each system needs to have an SOP that explains how to use it. Administration of the system may be an additional SOP. For instance, if a LIMS system allows input from scientists and technicians in a laboratory, they will need to have instructions for inputting and accessing data. An administrator, on the other hand, must know how to structure security access and archive data. Similarly, users of an electronic document system must know how to access the system and use it to initiate, review, or approve documents.

57. What SOPs Should You Have to Support Document and Record-Keeping Systems?

Since systems these days are either fully electronic or hybrid electronic and paper, there must be SOPs that support how systems function. Here are some SOPs to think about:

- Facilities Security. This is the first line of defense for your company records and activities. Such an SOP covers facility access control accounts, visitor policy, and loss management.

- Network Security. This is the second line of defense for your company records and activities. Such an SOP covers network user access, password requirements, mandatory password change intervals, screen saver password use, remote access, Internet access, and virus protection.

- System Backup. Such an SOP tells how records are backed up on networked servers, individual workstations, and parts of systems. It also covers media labeling, reuse, and destruction.

- Data Archiving. Such an SOP tells how to archive data to make more storage space available and how to make archived data retrievable for review and inspections.

- Computer System Event Recording. Such an SOP identifies logs for recording modifications to a system. Logs create an audit trail for the system by capturing the date of the event, description of the event, testing explanation, tester, and date of completion.

- Computer System Change Control. One change control process may be used for all systems or each system can have a system-specific change control procedure. Such SOPs identify logs to record modifications.

- Computer System Disaster Recovery. Such an SOP tells how systems can be brought back online following the loss of facility, hardware, software, connectivity, or data.

- Electronic Signature Policy. If a system employs electronic signatures, an SOP delineates how users are held accountable for actions initiated under electronic signature and that e-signatures are legally binding equivalents of wet signatures.

- Record Retention. Such an SOP tells how long the company retains records and how data can migrate from a system. The legal requirements for e-records are the same as for paper.

- Scanning. Such an SOP tells how to scan documents and verify replication.

- Computer System Validation. Such an SOP tells how to validate a computer system, usually for COTS software applications.

- E-Mail Policy. Such an SOP tells how e-mail is backed up, archived, and retained, and it may include deletion policies.

- Time Management. If the company has sites in different time zones, such an SOP tells how to handle time and date stamps across the organization.

- Software/Hardware Procurement. `Such an SOP tells how to evaluate potential vendors in relation to user requirements.

- Software Vendor Auditing. Such an SOP tells how a company evaluates the software development life cycle (SDLC), regulatory experience, and vendor and product history.

- Systems Inventory. Such an SOP tells how systems are inventoried, ranked according to risk, and analyzed for gaps with the industry standards. The inventory includes plans for upgrades or retirement.

- Software Development. If a company creates its own software, such an SOP tells how it the software development life cycle is performed and documented.

- Internal Auditing. Such an SOP tells how a company audits its own systems and provides an auditing schedule.

- Hosting a Compliance Inspection. Such an SOP tells the protocol for receiving investigators, what records the company makes available, who serves as a host, and how investigators/auditors access records and documents,

- Central Records Management. Such an SOP tells how the company stores, protects, and accesses paper records.

- Transitioning to an E-System. Such an SOP tells how documents will move into a new, validated system. Typically, an SOP like this retires after the process is done.

- Part 11 Committee. Companies with substantial resources often form Part 11 Committees to make decisions about systems. If they do, they should put a Part 11 committee SOP in place to explain the purpose, responsibilities, and protocol for action.

58. Must We Include Training Requirements in Every SOP?

No. Training is mandatory, and firms need to have an SOP that addresses training overall. To reiterate this requirement in each SOP is redundant.

59. What Happens If People Undergo Training, But Fail to Follow a Procedure?

Retraining is in order. If failure to follow a procedure is consistent, the company needs to look at the procedure itself to see if it reflects an efficient and workable process. It may be that the procedure requires revision. If the procedure is sound, the company may have a personnel problem, perhaps an employee who is unable to perform the task or willfully disregards the established procedure. In that case, reassignment of the employee to another work area or disciplinary action may be in order. If many people fail to follow a procedure, management must investigate possible language and prerequisite skill sets deficiencies.

REFERENCES

1. www.iso.org, accessed July 18, 2009.

2. www.fda.gov/regulations/guidance, International Conference on Harmonization Guidance.

3. Food and Drug Administration, Drug Information Comment FDA/CDER from Office of Compliance, e-mail to author, February 13, 2009.

4. Gough, Janet, and Hamrell, Michael. Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs): Why Companies Must Have Them, and Why They Need Them. Drug Inform J. 43:69–74, 2009.

5. Developing the compliance program guidance for pharmaceutical manufacturers, Federal Register 68(86), Monday, May 5, 2003/Notices.

6. 21 CFR Part 820.40 Document Controls.

Managing the Documentation Maze, By Janet Gough and David Nettleton

Copyright © 2010 John Wiley & Sons, Inc.