6

Sales Force Management

Introduction

This chapter addresses sales force metrics. It lists and defines the most common measures for determining whether sales force effort and coverage of customers and potential customers are adequate. We also discuss pipeline analysis, which is useful in making sales forecasts and in allocating sales force effort to different stages of the selling process. Pipeline metrics are used to monitor the sequence of selling activities, from lead generation, through follow-up, to conversion and sales. The most important of these represents the percentage of initial leads who ultimately buy. Other measures of activity, productivity, efficiency, and cost can be useful at each stage of the selling process.

|

Metric |

Construction |

Considerations |

Purpose |

6.1 |

Workload |

Hours required to service clients and prospects. |

Prospect numbers may be debatable. Time spent trying to convert prospects can vary by territory, salesperson, and potential client. |

Assess the number of salespeople required to service a territory and to ensure balanced workloads. |

6.1 |

Sales Potential Forecast |

This is the number of prospects and their buying power. |

Doesn’t assess the likelihood of converting “potential” accounts. Definitions of buying power are more art than science. |

Determine sales targets. Can also help identify territories worthy of allocation of limited sales resources. |

6.2 |

Sales Goal |

Individual sales projections may be based on a salesperson’s share of forecasted sales, on prior-year sales and a share of increased district projections, or on a management-designed weighting system. |

Setting individual targets on the basis of prior-year sales can discourage optimal performance, as strong performance in one year leads to more aggressive targets in the next. |

Set targets for individual salespeople and for territories. |

6.3 |

Sales Force Effectiveness |

Effectiveness metrics analyze sales in the context of various criteria, including calls, contacts, potential accounts, active accounts, buying power of territory, and expenses. |

Depends on factors that also affect sales potential and workload. |

Assess the performance of a salesperson or team. |

6.4 |

Compensation |

Total payments made to a salesperson, typically consisting of base salary, bonus, and/or commission. |

Perceived relationship between incentive reward and controllable activities may vary widely among industries and firms. |

Motivate maximum sales effort. Enable salespeople and management to track progress toward goals. |

6.4 |

Break-Even Number of Employees |

Sales revenue multiplied by margin net of commission divided by cost per staff member. |

Margins may vary across products, time, and salespeople. Sales are not independent of the number of salespeople. |

Determine the appropriate personnel level for a projected sales volume. |

6.5 |

Sales Funnel, Sales Pipeline |

Portrayal of the number of clients and potential clients at various stages of the sales cycle. |

Funnel dimensions depend on type of business and definition of potential clients. |

Monitor sales effort and project future sales. |

6.1Sales Force Coverage: Territories

Purpose: To create balanced sales territories.

There are a number of ways to analyze territories.1 Most commonly, territories are compared on the basis of their potential or size. This is an important exercise. If territories differ sharply or slip out of balance, sales personnel may be given too much or too little work. This can lead to under- or over-servicing of customers. Territories can contain multiple salespersons, but the same challenges apply in terms of ensuring that there is appropriate coverage for the territory.

When sales personnel are stretched too thin, the result can be an under-servicing of customers. This can cost a firm business because over-taxed salespeople engage in suboptimal levels of activity in a number of areas. They seek out too few leads, identify too few prospects, and spend too little time with current customers. Those customers, in turn, may take their business to alternate providers.

Over-servicing, in contrast, may raise costs and prices and may therefore indirectly reduce sales. Over-servicing in some territories may also lead to under-servicing in others.

Unbalanced territories also raise the problem of unfair distribution of sales potential among members of a sales force. This may result in distorted compensation and lead talented salespeople to leave a company, seeking superior balance and compensation.

Achieving an appropriate balance among territories is an important factor in maintaining satisfaction among customers, salespeople, and the company as a whole.

Construction

In defining or redefining territories, companies strive to

Balance workloads

Balance sales potential

Develop compact territories

Minimize disruptions during the redesign

These goals can have different effects on different stakeholders, as represented in Table 6.1.2

Table 6.1 Effects of Balancing Sales Territories

|

|

Balance the Workload |

Balance Sales Potential |

Minimize Disruption |

Develop Compact Territories |

Customers |

Responsiveness Relationships |

X |

|

X |

X |

|

Salespeople |

Earnings opportunities Manageable workload Reduced uncertainty Control of overnights |

X |

X |

X |

X

X |

Firm |

Sales results Effort control Motivation Travel cost control |

X X X |

X

X

|

X

X

|

X X |

Before designing new territories, a sales force manager should evaluate the workloads of all members of the sales team. The workload for a territory can be calculated as follows:

The sales potential in a territory can be determined as follows:

Sales Potential ($) = Number of Possible Accounts (#) * Buying Power ($)

Buying power is a dollar figure based on factors such as average income levels, number of businesses in a territory, average sales of those businesses, and population demographics. Buying power indices are generally specific to individual industries.

In addition to workload and sales potential, a third key metric is needed to compare territories. This is size or, more specifically, travel time. In this context, travel time is more useful than size because it more accurately represents the factor that size implies—that is, the amount of time needed to reach customers and potential customers. With changes in the way sales are done—most obviously via web-hosted meetings—geographic territorial size constraints are likely to be a less significant consideration for many firms, but workload still matters.

As a manager’s goal is to balance workload and potential among sales personnel, it can be beneficial to calculate combined metrics—such as sales potential or travel time—in order to make comparisons between territories.

Data Sources, Complications, and Cautions

Sales potential can be represented in a number of ways. Of these, the most basic is population—the number of potential accounts in a territory. In the copier case cited earlier, this might be the number of offices in a territory.

Estimating the size of a territory might involve simply calculating the geographic area that it covers. When salespeople have to travel to meet a client, average travel time is also important. Depending on the quality of roads, density of traffic, or distance between businesses, one may find that territories of equal area entail very different travel time requirements. Google Maps and similar services can generate helpful estimates.

Redefining territories is a famously difficult process. To perform it well, in addition to the metrics cited earlier, disruption of customer relationships and feelings of ownership among sales personnel must also be considered.

6.2Sales Force Objectives: Setting Goals

Purpose: To motivate sales personnel and establish benchmarks for evaluating and rewarding their performance.

In setting sales goals, managers strive to motivate their personnel to stretch themselves and generate the most sales possible. But they don’t want to set the bar too high. The correct goal levels will motivate all salespeople and reward most of them.

When planning sales goals, certain guidelines are important. Under the SMART (specific, measurable, attainable, realistic, and time-bound) strategy recommended by Jack D. Wilner, author of Seven Secrets to Successful Sales Management,3 goals should be

Specific: Goals should be specific to a department, a territory, and even a salesperson. They should be clear and applicable to each individual so that salespeople do not have to derive part of their goal.

Measurable: Measurable goals, expressed in concrete numbers such as “dollar sales” or “percentage increase,” enable salespeople to set precise targets and track their progress. Vague goals, such as “more” or “increased” sales, are not effective because they make it difficult to measure progress.

Attainable: Attainable goals are in the realm of possibility. They can be visualized and understood by both the manager and the salesperson.

Realistic: Realistic goals are set high enough to motivate but not so high that salespeople give up before they even start. (An alternative version of SMART uses Relevant to emphasis that goals should connect well to the firm’s wider objectives.)

Time-bound: Time-bound goals must be met within a precise time frame. This applies pressure to reach them sooner rather than later and defines an endpoint when results will be checked.

Construction

There are numerous ways of allotting a company’s forecast across its sales force. These methods are designed to set goals that are fair, achievable, and in line with historic results. Goals are stated in terms of sales totals for individual salespeople. In the following formulas, which encapsulate these methods, a district is composed of the individual territories of multiple salespeople.

A sales goal or allocation based on prior-year sales can be calculated as follows:4

A sales goal based on prior-year sales and the sales potential of a territory can be calculated as follows:

Sales goals can also be set by using a combined method, in which management assigns weightings to both the prior-year sales of each salesperson and the sales potential of each territory. These weightings are then used to calculate each salesperson’s percentage share of the relevant sales forecast, and percentage shares are used to calculate sales goals in dollar terms.

Sales Goal ($) = Weighted Share of Sales Allotment (%) * Forecasted Sales for District ($)

Data Sources, Complications, and Cautions

Sales goals are generally established by using combinations of bottom-up and top-down procedures. Frequently, top management sets objectives at a corporate level, and the sales manager allocates shares of that overall goal among the various members of the sales force.

Top management generally uses multiple metrics to forecast sales, including prior-year sales of the product in question, total prior-year sales in the relevant market, prior-year sales by competitors, and the company’s current market share. After the corporate sales forecast is derived, a sales force manager verifies that these targets are reasonable and pushes back where necessary. The manager then allots the projected sales among the sales force in a district, based at least in part on measures of individual performance from the prior year. Of greatest importance in this calculation are each salesperson’s historic percentage of sales and the sales potential of his or her territory.

It is important to reevaluate sales goals during the year to ensure that actual performance is running reasonably close to projections. If, at this checkpoint, it appears that more than 90% or less than 50% of the sales force is on track to achieve their goals, then it may be advisable to alter the goals. This will prevent salespeople from easing off too early because their goals are in sight or giving up because their goals are unattainable. In setting goals, one possible rule of thumb would be to plan for a success rate of 75%. That would ensure that enough salespeople reach their goals and that the goals are sufficiently challenging.

If “rebudgeting” becomes necessary, it is important to ensure it this is properly recorded. Unless care is taken, revised sales goals can slip out of alignment with financial budgets and the expectations of senior management.

6.3Sales Force Effectiveness: Measuring Effort, Potential, and Results

Purpose: To measure the performance of a sales force and of individual salespeople.

When analyzing the performance of a salesperson, a number of metrics can be compared. These can reveal more about the salesperson than can be gauged by his or her total sales.

Construction

An authoritative source lists the following ratios as useful in assessing the relative effectiveness of sales personnel:5

These formulas can be useful for comparing salespeople from different territories and for examining trends over time. They can reveal distinctions that can be obscured by total sales results, particularly in districts where territories vary in size, in number of potential accounts, or in buying power.

These ratios provide insight into the factors behind sales performance. If an individual’s sales per call ratio is low, for example, it might indicate that the salesperson in question needs training in moving customers toward larger purchases. Or it might indicate a lack of closing skills. If the sales per potential account or sales per buying power metric is low, the salesperson may not be doing enough to seek out new accounts. These metrics reveal much about prospecting and lead generation because they’re based on each salesperson’s entire territory, including potential as well as current customers. The sales per active account metric provides a useful indicator of a salesperson’s effectiveness in maximizing the value of existing customers.

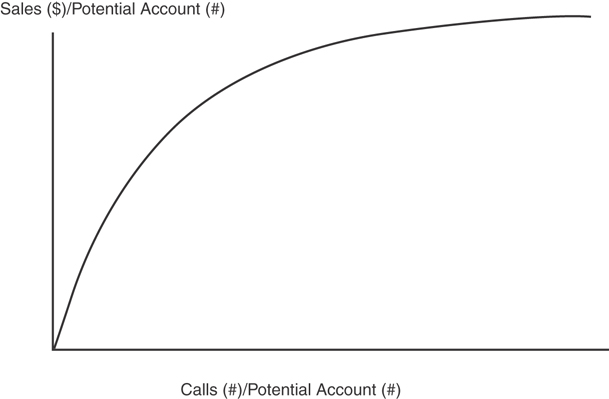

Although it is important to make the most of every call, a salesperson will not reach his or her goal in just one call. A certain amount of effort is required to complete sales. This can be represented graphically as shown in Figure 6.1.6

Figure 6.1 Sales Resulting from Calls to Customers

Although one can increase sales by expending more time and attention on a customer, at a certain point, a salesperson encounters diminishing returns in placing more calls to the same customers. Eventually, the incremental business generated by each call will be worth less than the cost of making the call.

In addition to the formulas described earlier, one other important measure of effectiveness is the ratio of expenses to sales. This cost metric is commonly expressed as a percentage of sales and is calculated as follows:

If this ratio is substantially higher for one salesperson than for others, it may indicate that the individual in question has poor control of his or her expenses. Examples of poor expense control could include making unnecessary trips to a client, overproducing product pamphlets, or hosting too many dinners. Alternatively, expenses may represent a high percentage of sales if an individual possesses poor closing skills.

A more challenging set of sales force performance metrics involves customer service. Customer service is difficult to measure because there are no concrete numbers representing it, other than repeat rates or customer complaints. Each of those is telling, but how can a sales manager evaluate the service provided to customers who are not repeating, leaving, or complaining? One possibility is to develop a survey, including an itemized scale to help customers quantify their opinions. After enough of these surveys are completed, managers will be able to calculate average scores for different service metrics. By comparing these with sales figures, managers can correlate sales with customer service and grade salespeople on their performance.

Data Sources, Complications, and Cautions

Calculating the effectiveness of a salesperson is not difficult, but it does require keeping track of a few important numbers. Fortunately, these are commonly tracked as part of sophisticated sales management and customer relationship management (CRM) software packages.

The most important statistics are the amount of each sale (in dollars) and the contribution generated by each sale. It may also be important to keep track of which items are sold if a salesperson has been instructed to emphasize a certain product line. Additional useful information would include measures of the number of calls made (including both face-to-face and phone meetings), total accounts active, and total accounts in the territory. Of these, the latter two are needed to calculate the buying power of a territory.

The largest problem in performance review is a tendency to rely on only one or two metrics. This can be dangerous because an individual’s performance on any one measure may be anomalous. A salesperson who generates $30,000 per call may be more valuable than one who generates $50,000 per call, for example, if the former generates greater sales per potential account. A salesperson in a small territory may generate low total contribution but high dollar sales per buying power. If this is true, it may be advisable to increase the size of that person’s territory. Another salesperson may show a dramatic increase in dollar sales per active account. If achieved by simply by eliminating weaker accounts, without generating incremental sales, this would not be grounds for reward. In reviewing sales personnel, managers are advised to evaluate as many performance metrics as possible.

Although the customer service survey described earlier is grounded upon a straightforward concept, managers can find it difficult to gather enough data—or sufficiently representative data—to make it useful. This could be because customers hesitate to fill out the surveys or because they do so only when they encounter a problem. A small sample size or a prevalence of negative responses might distort the results. Even so, some effort to measure customer satisfaction is needed to ensure that salespeople don’t emphasize the wrong issues—or neglect issues that have a substantial impact on customers’ lifetime value.

6.4Sales Force Compensation: Salary/Reward Mix

Purpose: To determine the mix of salary, bonus, and commission that will maximize sales generated by the sales force.

When designing a compensation plan for a sales force, managers face four key considerations: level of pay, mix between salary and incentive, measures of performance, and performance–payout relationships. The level of pay, or compensation, is the amount that a company plans to pay a salesperson over the course of a year. This can be viewed as a range because its total will vary with bonuses or commissions.

The mix between salary and incentive represents a key allocation within total compensation. Salary is a guaranteed sum of money. Incentives can take multiple forms, including bonuses or commissions. In the case of a bonus, a salesperson will receive a lump sum for reaching certain sales targets. With a commission, the incentive is incremental and is earned on each sale. In order to generate incentives, it is important to measure accurately the role a salesperson plays in each sale. The higher the level of causality that can be attributed to a salesperson, the easier it is to use an incentive system.

Various metrics can be used to measure a salesperson’s performance. With these, managers can evaluate a salesperson’s performance in the context of past, present, or future comparators, as follows:

The past: Measure the salesperson’s percentage growth in sales over prior-year results.

The present: Rank salespeople on the basis of current results.

The future: Measure the percentage of individual sales goals achieved by each salesperson.

Sales managers can also select the organizational level on which to focus an incentive plan. The disbursement of incentive rewards can be linked to results at the company, division, or product-line level. In measuring performance and designing compensation plans along all these dimensions, managers seek to align salespeople’s incentives with the goals of their firm.

Finally, a time period should be defined for measuring the performance of each salesperson.

Construction

Managers enjoy considerable freedom in designing compensation systems. The key is to start with a forecast for sales and a range within which each salesperson’s compensation should reside. After these elements are determined, there are many ways to motivate a salesperson.

In a multi-bonus system, the following formula can represent the compensation structure for a salesperson:

Compensation ($) = Salary ($) + Bonus 1 ($) + Bonus 2 ($)

In this system, bonus 1 might be attained at a level approximately halfway to the individual’s sales goal for the year. The second bonus might be awarded when that goal is met.

In a commission system, the following formula would represent compensation for a salesperson:

Compensation ($) = Salary ($) + [Sales ($) * Commission (%)]

Theoretically, in a 100% commission structure, salary might be set as low as $0. Many jurisdictions, however, place limits on such arrangements. Managers must ensure that their chosen compensation structures comply with employment law.

Managers can also combine bonus and commission structures by awarding bonuses on top of commissions at certain sales levels or by increasing the commission rate at certain sales levels.

After a sales compensation plan has been established, management may want to reevaluate the size of its sales force. Based on forecasts for the coming year, a firm may have room to hire more salespeople, or it may need to reduce the size of the sales force. On the basis of a given value for projected sales, managers can determine the break-even number of employees for a firm as follows:

Data Sources, Complications, and Cautions

Measurements commonly used in incentive plans include total sales, total contribution, market share, customer retention, and customer complaints. Because such a plan rewards a salesperson for reaching certain goals, these targets must be defined at the beginning of the year (or other time period). Continual tracking of these metrics will help both the salesperson and the company to plan for year-end compensation.

Timing is an important issue in incentive plans. A firm must collect data in a timely fashion so that both managers and salespeople know where they stand in relation to established goals. The time frame covered by a plan is another important consideration. If a company tries to generate incentives through weekly rewards, its compensation program can become too expensive and time-consuming to maintain. By contrast, if the program covers too long a period, it may slip out of alignment with company forecasts and goals. This could result in a sales force being paid too much or too little. To guard against these pitfalls, managers can develop a program that mixes both short- and long-term incentives. They can link some rewards to a simple, short-term metric, such as calls per week, and others to a more complex, long-term target, such as market share achieved in a year.

A further complication that can arise in incentive programs is the assignment of causality to individual salespeople. This can become a problem in a number of instances, including team collaborations in landing sales. In such a scenario, it can be difficult to determine which team members deserve which rewards. Consequently, managers may find it best to reward all members of the team with equal bonuses for meeting a goal.

A final concern: When an incentive program is implemented, it may reward the “wrong” salespeople. To avoid this, before activating any newly proposed program, sales managers are advised to apply that program to the prior year’s results as a test. A “good” plan usually rewards the salespeople whom the manager knows to be the best.

6.5Sales Force Tracking: Pipeline Analysis

Purpose: To forecast upcoming sales and evaluate workload distribution.

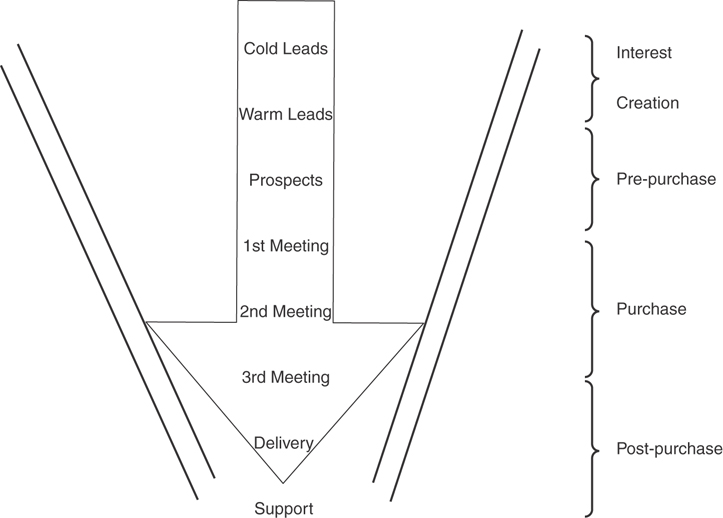

A convenient way to forecast sales in the short term and to keep an eye on sales force activity is to create a sales pipeline or sales funnel. Although this concept can be represented graphically, the data behind it are stored electronically in a database or spreadsheet.

The concept of the sales funnel originates in a well-known dynamic: If a sales force approaches a large number of potential customers, only a subset of them will actually make purchases. As salespeople proceed through multiple stages of customer interaction, a number of prospects are winnowed out. At the conclusion of each stage, fewer potential customers remain. By keeping track of the number of potential customers at each stage of the process, a sales force manager can balance the workload within a team and make accurate forecasts of sales.

This analysis is similar to the hierarchy of effects discussed in Section 2.7. Whereas the hierarchy of effects focuses on the impact of advertising or mass media, the sales funnel is used to track individual customers (often by name) and sales force efforts.

Construction

In order to conceptualize a sales funnel or pipeline, it is helpful to draw a diagram showing the stages of the selling process (see Figure 6.2). At any point in the year, it is likely that all stages of the pipeline will include some number of customers. As Figure 6.2 illustrates, although there may be a large number of potential customers, those who actually make purchases represent only a percentage of these original leads.

Figure 6.2 Sales Force Funnel

Interest Creation

Interest creation entails building awareness of a product through such activities as trade shows, direct mail, and advertising. In the course of interest creation, salespeople can also generate leads. That is, they can identify targets to add to their pool of potential customers. Two main classifications of leads include cold leads and warm leads.

Cold Lead: A lead that has not specifically expressed interest. These can be identified through mailing lists, phone books, business listings, and so on.

Warm Lead: A lead that is expected to be responsive. These potential customers may have registered through a website or requested product information, for example.

Pre-Purchase

The pre-purchase stage involves identifying prospects from among cold and warm leads. Salespeople make this distinction through initial meetings with leads, in which they explain product features and benefits, and cooperate in problem solving with the customer. The desired result of such an early-stage meeting is not a sale but rather the identification of a prospect and the scheduling of another meeting.

Prospect: A potential customer who has been identified as a likely buyer, possessing the ability and willingness to buy.8

Purchase

After prospects are identified and agree to additional calls, salespeople engage in second and third meetings with them. It is in these sessions that traditional “selling” takes place. Salespeople engage in persuading, negotiating, and/or bidding. If a purchase is agreed upon, a salesperson can close the deal through a written proposal, contract, or order.

Post-Purchase

After a customer has made a purchase, there is still considerable work to be done. This includes delivery of the product or service, installation (if necessary), collection of payments, and possibly training. There is then an ongoing commitment to customer service.

After salespeople visualize the different stages represented in a sales funnel, they can track their customers and accounts more accurately. They can do this electronically by using a database or spreadsheet. If a sales pipeline file is maintained on a shared drive, any member of a sales force will be able to update the relevant data on a regular basis. This will also enable a sales manager to view the progress of the team at any point in time. Table 6.2 is an example of a spreadsheet form of a sales funnel.

Table 6.2 Spreadsheet Sales Funnel

Salesperson |

Interest Creation |

Pre-purchase |

Post-purchase |

||||

Cold Leads |

Warm Leads |

Prospects |

1st/2nd Meeting |

2nd/3rd Meeting |

Delivery |

Support |

|

Sandy |

56 |

30 |

19 |

5 |

8 |

7 |

25 |

Bob |

79 |

51 |

33 |

16 |

4 |

14 |

35 |

A manager can use the information stored in such a funnel to prepare for sales in the near future. This is a form of pipeline analysis. When a firm faces inventory issues, or when sales goals are being missed, this represents vital information. By applying historical averages, a sales or marketing manager can improve sales forecasts by using the data in a sales funnel. This can be done manually or with specialized software. The underlying assumption behind a sales funnel is that failure at any stage eliminates a prospect from the funnel. The following example illustrates how this bottom-up forecasting could be applied.

Data Sources, Complications, and Cautions

In order to populate a sales funnel correctly, salespeople must maintain records of all their current and potential customers and the status of each within the purchase process. Each salesperson must also share this information, which can then be aggregated in a comprehensive database of sales force activities. By applying assumptions to these—including assumptions drawn from historical sales results—a firm can project future sales. For example, if 25% of warm leads are generally converted to sales within two months, and 200 warm leads currently appear in a sales funnel, management can estimate that 50 of these will be converted to sales within two months.

At times, the use of a sales funnel leads to the pitfall of over-prospecting. The incremental contribution likely to be generated by a customer should be compared to the probable cost of acquiring that customer, using customer lifetime value metrics as appropriate.

Difficulties in the sales cycle can also arise when a salesperson judges that a potential customer may be a prospect because he or she has the willingness and ability to buy. To solidify this judgment, the salesperson must also confirm that either the customer possesses the authority or is likely to obtain approval to buy.

Further Reading

Jordan, Jason, and Michelle Vazzana. (2011). Cracking the Sales Management Code: The Secrets to Measuring and Managing Sales Performance. McGraw-Hill Education.