Sharia-compliant investments and wealth management

Sharia-compliant estate distribution and Islamic wills by Haroon Rashid

INTRODUCTION

Islam has a profound effect on how Muslims invest and manage their wealth. The following are key influencing factors:

- Investments must be sharia-compliant – the subject/activity underpinning the financial transaction has to be a permitted activity (e.g. cannot relate to alcohol, gambling, etc.), it has to be free of interest, it has to be free from contractual ambiguity/uncertainty and an investor can seek a return only if they take some commercial risk in the investments they are making.

- Contractual principles (as per Chapter 4) need to be adhered to.

- The sharia has comprehensive guidance on how one’s wealth should be distributed on death, i.e. inheritance laws.

- It is obligatory for Muslims who possess a certain minimum level of wealth to give a part of their wealth in charity every year (system of zakat).

- As we saw in Chapter 3, Islam has a distinctive perspective on wealth and upholds certain principles and values with respect to wealth.

In this chapter, we will focus on:

- sharia-compliant investments – what are the key asset classes and key principles underpinning each asset class;

- zakat – the obligatory charity due on wealth acquired. The chief executive of the National Zakat Foundation in the UK, Iqbal Nasim, discusses the key principles underpinning this important area;

- Islamic wills and estate planning – a leading practitioner in this field, Haroon Rashid, gives an explanation of how important this area is from an Islamic perspective, the key principles underpinning Islamic inheritance law, and the implications for practitioners in light of practical issues such as taxes levied on inheritance. This area is a fundamental part of sharia-compliant wealth management.

SHARIA-COMPLIANT INVESTMENTS

There is a need for investments that meet the requirements of the sharia – invariably planning for life events such as university fees for our children or having the best possible income in retirement, or simply putting surplus monies to productive use requires investing money for the future.

There are now more than 1,000 sharia-compliant funds around the globe (see Figure 7.1),1 with $56 billion invested. While this is only 4.7 per cent of global Islamic assets, investment into sharia-compliant funds is growing at an impressive rate and there is growing traction for such investments among non-Muslim investors. The range, depth and quality of sharia compliant investments have improved over time.

Figure 7.1 Number of sharia-compliant funds globally, 2007–13

Table 7.1 Islamic funds broken down by domicile, number and size

| Domicile | No. of funds | Assets under management ($ million) |

|---|---|---|

| Malaysia | 263 | 10,164 |

| Saudi Arabia | 163 | 6,056 |

| Luxembourg | 111 | 3,401 |

| Pakistan | 62 | 2,364 |

| Indonesia | 53 | 2,157 |

| Ireland | 53 | 1,742 |

| Jersey | 33 | 1,286 |

| Kuwait | 26 | 705 |

| South Africa | 21 | 663 |

| Canada | 19 | 248 |

| United Kingdom | 12 | 248 |

| UAE | 12 | 231 |

| Other | 91 | 248 |

Malaysia, Saudi Arabia and Luxembourg are recognised as the leading hubs for Islamic funds, collectively playing host to 71 per cent of Islamic funds globally.2 Table 7.1 shows the breakdown of funds in terms of their domicile, number and size.

Key asset classes

Asset classes in the sharia space are similar to the mainstream conventional market. Clearly interest-based investments are prohibited. Instead within the sharia-compliant space, asset classes include categories referred to as ‘Islamic deposit accounts and money market funds’ and sukuk (as discussed in Chapter 6 and often referred to as Islamic bonds). The broad asset classes offered therefore are:

- Islamic deposit accounts and money market funds;

- property;

- equities;

- commodities;

- sukuk.

Some funds are structured to give exposure to more than one asset class and as such are referred to as ‘mixed funds’.

Figure 7.2 is a classic depiction of the asset classes in terms of the risk and return trade-off across different asset classes – this is very generic and may not hold true for all investments.

Figure 7.2 Risk and return trade-off across different asset classes

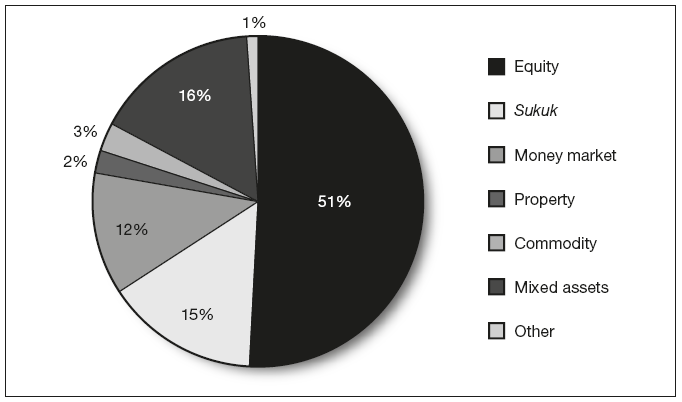

In terms of the relative number of funds available in each asset class, the Thomson Reuters ‘Global Islamic Asset Management Report 2014’ reported the breakdown for data collected in 2013 shown in Figure 7.3.

Figure 7.3 Number of funds available in each asset class, 2013

Source: Thomson Reuters, ‘Global Islamic Asset Management Report 2014’.

Islamic deposit accounts and money market funds

While money market funds, as in Figure 7.3, are not as common as equity or sukuk funds, they are the largest asset class in terms of monies invested, as outlined in the Thomson Reuters report. The report highlights that this asset class accounted for more than $20 billion (over one-third of the investment into Islamic funds) in 2013.

Islamic deposit/savings accounts tend to operate on either a wakala or mudarabah basis, as illustrated in Chapter 5. Here the return is not interest but a profit delivered to the depositor from investing in sharia-compliant investments. The underlying investments will tend to be low risk with a high level of certainty as to what the return to the investor will be. For example, Al Rayan Bank’s deposit accounts offer returns to investors based primarily on investments into its own property finance schemes. The rate of return on Al Rayan Bank’s property finance schemes is known; the main risk to investors is customers defaulting on making payments. The default rate tends to be very low because of the relatively high entry requirements to secure property finance, e.g. the upfront deposit required from customers by the bank tends to be quite high – at the time of writing the minimum deposit required was 20 per cent. Hence the return to depositors is highly predictable and certain.

Some banks have in the past and some continue to provide Islamic deposit accounts based on commodity murabaha. As discussed in Chapter 5 this practice has come under quite a lot of criticism due to its synthetic nature and countries such as Oman have not permitted its use.

Sharia-compliant money market funds tend to invest in a portfolio of Islamic deposit accounts, sukuk and other ‘fixed-income’ type investments such as ijarah-based investments. Such funds, through pooling and scale, can command better returns than individuals investing on their own.

Here are two examples of sharia-compliant money market funds.

Example

The Gulf-based bank Emirates NBD has an Islamic money market fund. A description of the fund from Emirates NBD is as follows:

The Emirates Islamic Money Market Fund (the ‘Fund’) is a Shari’a compliant open ended fund that aims to achieve a higher profit return than traditional Shari’a compliant bank deposits of similar liquidity, predominantly from a diversified portfolio of Shari’a compliant money market instruments including the use of collectives investing in such instruments. The Fund will seek over time to acquire a diversified portfolio, including, but not limited to, instruments such as (or schemes investing in) Islamic deposits, Shari’a compliant synthetic instruments, murabaha, sukuk and international trade contracts.

Source: www.emiratesnbd.co.uk/en/

The reference to sharia-compliant synthetic instruments would suggest the fund does invest in commodity murabaha-based investments.

Example

The second example is from National Bank of Kuwait. Again this is an extract from its website, providing information on the fund:

The Watani USD Money Market Fund According to Islamic shariah principles is an open-ended fund, which aims to generate returns that are in excess of the USD Fixed Deposit rates. This will be achieved through investing in high-quality money market instruments such as murabaha transactions and ijarah according to Islamic shariah principles.

Source: www.kuwait.nbk.com

In this case, ijarah is mentioned. Ijarah lends itself well to providing investors a relatively low-risk, predictable income stream – which is in keeping with the risk and return profile of this asset class. As we will see below, ijarah also features strongly within the sukuk asset class.

Sukuk

As we saw in Chapter 6, sukuk as a sharia-compliant capital markets instrument has grown impressively for more than a decade. As an asset class to invest in, they have become more accessible because:

- many sukuk are now listed on recognised stock exchanges around the world;

- the growth and listings have enabled an active secondary market to develop, which in turn has enabled sukuk funds to emerge. Indeed, sukuk funds now account for 15 per cent of the total sharia-compliant funds on the market, and around $4 billion is invested in sukuk-based mutual funds (just under 10 per cent of the total investment into Islamic mutual funds).3

The sukuk asset class is an important part of the Islamic investment universe – it often provides a fixed-income investment instrument that is tradable (hence the fact it is often referred to as an Islamic bond). Investors, whether individuals or institutions such as banks, often want these types of instruments as opposed to equities or property-based investments which tend to be more risky and/or illiquid.

As we discussed in Chapter 6, ijarah is a popular investment technique when structuring sukuk. This is because an ijarah usually allows a predictable and defined income stream for investors with a known exit price at maturity and the investor is able to trade the sukuk. All these features are appealing to investors. Within the sharia-compliant investment universe there are a number of leasing funds comprising assets that are purchased by the fund and leased out. Investment into such funds will therefore often have a similar risk profile to sukuk-based investments.

An example of a sukuk fund is the Global Sukuk Plus Fund provided by QIB UK. An extract from a factsheet4 of the fund reads as follows:

The Fund’s assets are invested in sukuk issued by sovereign, quasi sovereign and corporate issuers in accordance with the Fund’s investment guidelines. Sukuk are sourced globally.

The tradability and liquidity of sukuk investments have improved over time as the market has expanded and an increasing number of sukuk have been listed on the major stock exchanges around the world. However, compared with the relatively large and mature conventional bond market, the sukuk market is not as liquid. This will improve as the market expands further.

Property

Investment into property has been very popular across the globe for decades and many investors have made significant returns as property prices generally across the world have risen significantly.

As an asset class, it lends itself well to sharia-compliant investing because:

- the investment relates to a physical asset – hence is asset-backed;

- the returns to investors can be in the form of rentals and/or profit on sale of properties – all of which is sharia-compliant.

As we saw earlier in the chapter, property funds accounted for only 2 per cent of the total sharia-compliant fund universe in 2013. However, many investors have and want to invest directly into property. The challenge they often face is getting access to sharia-compliant finance to purchase property. Access to sharia-compliant property finance has improved significantly in the last decade as Islamic banks and international banks with an Islamic window/offering have had quite a strong focus in this area. In a country like the United Kingdom, where Islamic finance is very much a niche area, you can now find sharia-compliant property finance for buying your home, buy-to-let residential investments, commercial property finance and to some extent real estate development finance. This will undoubtedly spur on the demand from individuals looking to invest in the property sector in a sharia-compliant way.

Access to sharia-compliant funding is also an important factor for the provision of sharia-compliant property investments from providers. An example is an investment offered by a company called London Central Portfolio Ltd (LCP). In recent years the company has started offering investment opportunities into the prime central London residential market on a sharia-compliant basis. A feature of its business model and investment proposition is to fund the investments through sharia-compliant finance as well as monies received from investors. Its latest investment memorandum5 says the following:

It is anticipated that shariah compliant leverage will be obtained on the best terms offered. The terms below are indicative...:

Term: From drawdown for five years Security: First legal charge over the portfolio Leverage to refurbished value: Up to 50% Profit rate cover ratio: 135% at all times Profit rate periods: Six months and/or 5 years The level of leverage is set at 60% of the purchase price, which is estimated to represent 50% of the refurbished value at the beginning of the Investment Period. Property values would therefore have to fall in the region of 50% before negative equity would be reached.

Thus the availability of sharia-compliant finance has helped the provision of such investment options in the property sector.

Equity

As we saw earlier, equity funds are the most popular type of fund, representing 51 per cent of the total sharia-compliant fund universe. Investing into equities equates to buying a stake in a business. Naturally the issue of whether or not an equity investment is sharia-compliant is broadly dependent on the sharia permissibility of the activities that the business engages in and the financial make-up of the company.

With so many sharia-compliant equity funds now in existence, the criteria used to determine sharia compliance are relatively well established and mainstream. Many of the major stock exchanges around the globe have indices made up of equities that comply with the sharia criteria: for example, there is the Dow Jones Islamic Market Index and the FTSE Shariah Global Equity Index.

The criteria used to determine sharia compliance essentially come down to two parts.

- The industry screen. This looks at the industry in which the company is involved. Businesses involved in activities prohibited by the sharia such as drinking alcohol, eating pork, gambling and pornography would clearly not qualify as eligible sharia-compliant investments. For example, the Dow Jones Islamic Market Index screens out companies involved in the following sectors:

- alcohol;

- pork-related products;

- conventional financial services;

- entertainment;

- tobacco;

- weapons and defence.

- The financial screen. The current reality of investing in equities listed on all the major stock exchanges is that very few companies will be fully sharia-compliant. While there are plenty of companies that engage in lines of business that are fully sharia-compliant (i.e. they avoid the type of industries listed above), the overwhelming majority of companies will have some involvement in interest – either through interest-based borrowings or through interest accruing on monies held in a conventional bank account.

The mainstream sharia scholars have opined to allow investment into equities that have these ‘impurities’ as long as they are below certain thresholds. They have justified this on the following grounds:

- Any ‘impure income’ such as interest received must be calculated and given to charity, so as to purify the return to investors. In this sense there is zero tolerance on earning any interest.

- Stock markets perform an important function in the economy in providing the platform for businesses to gain equity funding. This funding facilitates the running and growth of businesses, which in turn creates jobs and prosperity for others. Therefore at this stage in the development of Islamic finance (relative to the established nature of global stock markets) it may harm the public interest not to allow investment into equities listed on the stock market.

- Scholars have taken the view that they will allow stock market investment as long the ‘impurities’ are below certain thresholds – ensuring that the overriding core and majority of the investment is sharia-compliant. Scholars have also stipulated that over time they will tighten these thresholds so the tolerated level of impurity diminishes.

The financial screens used and approved by scholars are broadly similar across different organisations and jurisdictions but are not uniform. This is an example of where, in my opinion, standardisation would benefit the industry, by having one set of criteria agreed by a central sharia board/governing body presiding over the entire Islamic finance industry.

AAOIFI, the Bahrain-based standard-setting body for the Islamic finance industry, has stipulated the following ratios for the financial screen in terms of investing into equities (AAOIFI sharia standard 21):

- Conventional debt/Total market capitalisation <30%.

- (Cash + cash deposits)/Total market capitalisation <30%.

- (Total interest + income from non-compliant activities)/Revenue <5%.

Let us now look at the rationale underpinning these ratios.

Conventional debt/Total market capitalisation <30%

Clearly, many companies have taken on conventional, interest-bearing debt to partly finance the business. From a sharia perspective, paying interest as well as receiving interest is not permissible. For the reasons mentioned above, scholars have generally permitted up to one-third (30 per cent in the case of AAOIFI) of the capital structure of a company to be financed by conventional interest-bearing debt.

What do you define as the capital structure of the company?

By this I mean, what do you measure conventional interest-bearing debt against to see whether it exceeds 30 per cent or 33 per cent? In practice, different measures are being used in the industry. For example, as we saw above, AAOIFI has used ‘total market capitalisation’ as the value, the FTSE Shariah Global Equity Index and the MSCI Islamic Index use ‘total assets’, and the Dow Jones Islamic Market Index uses ‘trailing 24-month average market capitalisation’ as the value.

There are pros and cons in using any of these measures – those that use market capitalisation will tend to have a larger pool of eligible stocks as the market value of a company tends to be greater than the value of its total assets. However, market values of listed companies can be volatile and stocks may end up fluctuating in and out of sharia compliance. Again a standard approach to this issue would be welcome from both an industry and a consumer perspective. It also highlights the point that although AAOIFI is the leading standard-setting body within the industry, the guidance and standards it produces are not mandatory and therefore organisations have produced their own criteria which their own sharia scholars have endorsed and certified.

Why have scholars used one-third as the fraction they have allowed?

Prophet Muhammad is reported to have said: ‘One third is big or abundant’ (source: Imam Tirmidhi). So scholars have used this as a basis for setting this particular threshold. This threshold is considerably more than the 5 per cent threshold set for non-permissible income. Anything that affects the income of the company is seen as a ‘greater impurity’ – thus not only is the threshold lower but any impermissible income has to be given to charity.

(Cash + cash deposits)/Total market capitalisation <30%

Trading cash at anything but par would be regarded as interest. So if a company’s asset base has a significant amount of cash, then the trading of shares in that company is getting closer to trading cash. Based on the premise that one-third is regarded as ‘abundant’ in the sharia, scholars have stipulated that cash plus cash deposits must not exceed one-third of a company’s assets.

Sharia-compliant investing: more than just avoiding prohibitions

It is clear that for investments to qualify as sharia-compliant they must not violate certain prohibitions and that the subject matter of the investment must be permissible by Islamic law. However, there is a broader picture. The rules of the sharia are designed to achieve certain objectives (referred to as maqasid al sharia in Arabic).

Renowned Muslim scholar Abu Hamid Al-Ghazali (1058 to 1111) described the objectives of the sharia as follows:

The very objective of the shariah is to promote the well-being of the people, which lies in safeguarding their faith (deen), their lives (nafs), their intellect (ñaql), their posterity (nasl), and their wealth (mal). Whatever ensures the safeguarding of these five serves public interest and is desirable, and whatever hurts them is against public interest and its removal is desirable.

Therefore there is clearly a call for sharia-compliant investments to be in ventures and sectors that serve to enhance and protect the public interest. In this broader context, the Islamic teachings would encourage investment into areas such as renewable/green energy, social housing and fair trade farming. Similarly, in addition to prohibiting investment into areas considered haram, such as alcohol and gambling, the sharia in this broader context would discourage investment into areas that serve to harm the public interest, such as projects that harm the environment or exploit ‘cheap’ labour.

Sharia-compliant investments in substance have a broader mandate than merely not violating certain prohibitions. Indeed, there is a strong affiliation with socially responsible investment (SRI) and ethical investments. However, one has to be careful: the screening criteria used in the mainstream SRI and ethical investment space are not usually totally in line with sharia criteria. For example, such criteria will not look to screen out companies with interest-bearing debt.

There has been a growing call and consensus that the Islamic finance investment industry needs to increasingly position its value proposition in the SRI/ethical space. This has a resonance with the overall objectives of the sharia and with human beings of all faiths or no faith. This in turn will make the proposition more inclusive and appealing to a much broader audience – a ‘win-win’ situation for all.

It is worth noting, too, that the sharia principles promote certain investment and economic behaviours that are beneficial to the public interest:

- Investors, to earn a legitimate return, must take some commercial and/or asset risk in what they are investing in; they cannot merely take credit risk as in the case of an interest-bearing loan. This in turn means investors have to invest in real projects and businesses, which in the long run means the economy’s foundation will be the production of real goods and services. This is generally seen as healthy as opposed to an over-reliance on the financial sector, dominated by interest-bearing transactions and banks. The structure of the UK economy, for example, has been criticised for its over-reliance on the financial services sector and a relatively weak manufacturing sector.

- Equity finance is promoted and debt instruments demoted relative to conventional finance – this in turn promotes investors and financiers investing in projects and businesses with the best business credentials as opposed to those with the best collateral or credit rating. Again for the long-term health of the economy this will be better, ensuring the finance is allocated to the best business ventures. Unhealthy debt levels and a recognition that small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), to flourish, need access to equity finance are contemporary topical issues in the mainstream.

As mentioned in the introduction we now go on to look at two very important aspects of Islamic wealth management: the Islamic duty to give a portion of one’s wealth to charity every year, and the clear and overt guidance in the sharia on how to distribute one’s wealth on death.

ZAKAT BY IQBAL NASIM

The core obligatory acts of worship in Islam are five:

- The testimony of faith (shahadah).

- Five daily prayers (salat).

- Annual alms-giving (zakat).

- Fasting in the month of Ramadan (sawm).

- The pilgrimage to Mecca (hajj).

Zakat is therefore the third of the five pillars and the only one that is intrinsically connected to one’s wealth. Specifically it involves an annual transfer of fixed portions of certain types of one’s wealth to an eligible recipient, provided that one’s net zakatable assets are above a given threshold (nisab). As a core act of worship, there are strict rules that govern the calculation, payment and distribution of zakat, all of which contribute ultimately to its proper fulfilment and acceptance.

Given its importance, zakat is supposed to be administered at state level and in many Muslim countries this is the case. Kuwait and Malaysia stand out as two countries where the zakat systems appear to be the most developed. In non-Muslim countries where Muslim communities exist, organisations and charities that collect and distribute zakat have emerged, typically relying on local Muslim scholars to guide their policies and procedures.

Linguistic meaning and spiritual significance

The word zakat appears 32 times in the Qur’an and it is noteworthy that, on 28 of these occasions, its mention is conjoined with reference to salat (prayer), the second pillar. Indeed, the two concepts are mentioned in many places as core pillars of pre-Islamic prophets and faiths, as if to remind us that prayer and charity have always been utterly fundamental practices of anyone who holds a belief in God.

Linguistically, the word zakat carries meanings of purification, growth and blessing. These literal translations hold great significance when it comes to the spiritual importance of zakat. By paying zakat, one is purifying one’s soul from miserliness and greed, purifying one’s wealth and laying the foundations for a more blessed and prosperous future. By contrast, abstaining from paying one’s zakat is considered to be a way of inadvertently sullying all of one’s wealth and possibly leading to a less fortunate outcome in terms of financial prosperity.

Therefore, Muslims see zakat as a core part of sensible wealth management. In fact, the zakat payer simply considers a certain portion of his or her wealth every year as being the God-given right of someone who qualifies as an eligible recipient. The zakat payer is a temporary guardian over this portion until it is transferred to the rightful owner. Zakat is not considered in the same way as conventional charity, whereby a donor may feel that he or she is conferring a favour to the beneficiaries of a charitable initiative. Rather, zakat is to be seen through a lens of duty, responsibility and honouring the basic rights of others.

Other forms of charity

As mentioned, all aspects of the payment and distribution of zakat come with specific parameters and zakat is considered to be an obligatory act. Outside of zakat, however, voluntary charity (sadaqah) is heavily encouraged and has few, if any, restrictions in terms of amounts given and causes supported.

It is important to understand that not all valid causes for support are necessarily taken care of via zakat. It is simply the minimum requirement and therefore addresses basic needs. Beyond zakat, voluntary giving, the establishment of endowments and parallel fiscal systems (in a Muslim country) would all need to exist for a well-rounded approach to fulfilling the overall needs of a community.

Paying Zakat

Who pays Zakat?

Muslim scholars agree that once someone meets the following criteria, he or she must pay Zakat:

- To be Muslim.

- To have reached the age of physical maturity (and therefore personal accountability from an Islamic perspective).

- To be of sound mind.

- To have been in possession, for the period of one lunar year, of net zakatable assets whose value equals or exceeds a given threshold (nisab).

Where there is some disagreement is in relation to points 2 and 3 above. The majority of Muslim scholars hold that even though they are conditions for all other acts of worship, neither being of the age of physical maturity nor being of sound mind are necessary conditions for zakat to be paid on one’s wealth, i.e. if savings have accumulated in a child’s name or if someone who is mentally incapacitated possesses the necessary quantum of wealth, then zakat is due in both cases, with the parent or guardian being responsible for fulfilling the calculation and payment.

The other important factor here is the definition of the nisab, or threshold above which zakat becomes due. The first point to note is that the nisab varies for different asset classes within zakatable wealth. So, for example, cattle and agricultural produce are subject to zakat, with specific numbers and measures to determine whether any zakat is due and if so, how much.

For most conventional assets today, i.e. cash, business stock and other investments, the traditional measure of the nisab in gold and silver terms is used to determine an equivalent value in today’s currency.

Since real gold and silver coins were effectively the cash of the day at the time of Prophet Muhammad, he defined the nisab accordingly, equating to approximately 85 g of gold and 595 g of silver. As of August 2014, using live gold and silver prices, the nisab values are approximately £2,100 and £240 respectively. Muslim scholars advocate that, where one’s only asset is gold, the threshold of gold should be used. But where (as is far more likely) one possesses a mix of assets, the silver threshold should be used. Therefore, if one’s net zakatable assets are valued at £1,000, zakat should be calculated at 2.5 per cent and £25 should be paid.

When should it be paid?

Zakat is paid once every lunar year. The zakat payer must have a fixed zakat anniversary in the lunar calendar, this being the date that he or she will analyse their financial situation and calculate the zakat they owe. Zakat is therefore very much a balance sheet calculation. Once calculated, zakat should be paid immediately or as soon as possible. In most cases in the United Kingdom, this is done directly to registered charities. However, in some cases, a zakat payer may wish to pay their zakat directly by hand to a needy person whom he or she may not meet for some time. In this case, it is valid to delay the payment of zakat up to a maximum of one lunar year, i.e. it must be paid before the next zakat becomes due.

Zakat can be paid in advance of the calculation date. In this case, one might pay in monthly instalments or on one-off occasions, perhaps in response to a particular charitable appeal. In this case, when it comes to making the annual consideration of zakat, the calculation process remains the same but whatever has already been paid can be subtracted from the amount owed and the balance can then be discharged. If the zakat paid to date ends up exceeding the amount owed, then unfortunately there are no refunds. The surplus amount will simply be considered as supplementary or voluntary charity. Finally, the intention of fulfilling one’s zakat at the time of payment is critical. A person cannot retrospectively include general charitable donations that were not intended as zakat as part of their zakat fulfilment at a later date.

Where should it be paid?

Zakat should be paid either directly to an individual or cause that is known to be eligible to receive zakat, otherwise to a credible organisation or state body that is trustworthy when it comes to administering zakat funds.

How should it be calculated?

The basic principle of zakat calculation is that all items for personal use are exempt from zakat except for cash and, in the opinion of some scholars, gold and silver. A person’s house, car, clothes, etc. are not subject to zakat.

The essential steps of a zakat calculation are as follows:

- Add up the value of all of the zakatable assets.

- Calculate and subtract qualifying debts and liabilities.

- Compare the net value against the nisab (threshold).

- If the net zakatable assets equal or exceed the threshold then zakat is due on the total net value at a rate of 2.5 per cent.

The conventional assets and liabilities for a zakat calculation are shown below. For the sake of simplicity and relevance, zakatable assets such as minerals, crops and cattle are excluded here.

Zakatable assets

Cash and liquid investments

Cash and liquid investments are fully subject to zakat. This includes cash in all types of bank accounts, in a person’s wallet and under the mattress. If interest has been earned on liquid investments, then it should be given to charity separately and only the principal amount should be noted for zakat purposes.

Gold and silver

Some scholars consider gold and silver to be intrinsically subject to zakat, meaning that gold and silver jewellery, whether used as personal items or simply stored, would be subject to zakat.

Most scholars are of the opinion that if such items are worn and are held for personal utility, no zakat is due. However, if they are kept as an investment or simply hoarded, then zakat would be due.

The value of gold and silver, whether in jewellery form or held as bars or biscuits, can be calculated by a jeweller based on the selling price.

Business assets

These include cash and business assets for which the primary intention is to sell them on at a profit, such as stocks of finished goods, work in progress and raw materials. It also includes receivables, i.e. monies owed to businesses.

All business assets should be valued at their current market price. For finished goods, this should be their retail sale price. For unfinished goods, this should be whatever price one expects the unfinished good to fetch on the zakat anniversary date.

Shares and equity investments

If shares are purchased with the express intention of resale then the entire holding is subject to zakat at market value. If, however, shares are purchased as an investment to generate dividends, then as zakat is due only on the zakatable assets of the firm, a realistic attempt must be made to calculate the percentage of the shareholding relating to zakatable assets.

Any dividends received should be added to one’s cash balance for zakat purposes.

Property and other fixed assets

The house in which a person lives is not subject to zakat. If a property or other fixed asset has been purchased with the express intention to resell, then the entire value of the property/asset is subject to zakat. If there is any other intention, it is not subject to zakat.

Any rental income from properties owned should be added to a person’s cash balance for zakat purposes.

Pension

For monies set aside for pensions prior to retirement, zakat is payable only if the pension assets are being invested on behalf of the pension holder and the value of a person’s investments/pension pot can be specifically determined. If pension monies are being invested, the zakat liability will be determined by the nature of the investment (property or shares, etc. as per the third and fourth points above).

Debts owed to oneself

Zakat is payable on strong debts, i.e. money that is owed to somebody that he or she is confident will be repaid. This may include personal loans to friends and family. This does not include outstanding wages, dowry or inheritance.

Debts and liabilities

Not all debts and liabilities are deductible for zakat purposes. For example, the outstanding portion of long-term debts, such as a mortgage or a personal loan from a bank that are repayable by instalments, should not be deducted. Some scholars do allow for up to a year’s worth of the principal portion of such debts to be subtracted, but this allowance should be taken only if one’s ability to meet the repayments is likely to be adversely affected by excluding them from one’s zakat calculation. That said, personal loans among friends and family are deductible since they can be immediately recalled at any time.

Upcoming bills and liabilities are not to be deducted. However, outstanding or overdue liabilities can be subtracted, including those where there is a legal/formal/signed commitment to an upcoming payment.

The principles apply to both personal and business situations.

Final calculation and payment

Once all the zakatable assets have been valued and all relevant debts/liabilities have been subtracted, then the net value should be compared to the nisab (threshold) and if the figure is above the threshold, 2.5 per cent of the total net zakatable assets should be paid as zakat.

Example

Abdullah has £10,000 of zakatable assets and £6,000 of outstanding debts to friends and family. Net zakatable assets are therefore £4,000. Since this figure is above the nisab, zakat is due at 2.5 per cent, i.e. £100 is payable.

Distributing zakat

To whom is zakat distributed?

The Qur’an (Chapter 9, verse 60) specifies eight categories for the distribution of zakat:

- The poor.

- The needy.

- Those employed to administer zakat.

- Those whose hearts are to be reconciled.

- Those in slavery.

- Those in debt.

- In the way of God.

- The destitute traveller.

Each of the above categories has distinct criteria, and discussions as to exact definitions of some of the categories in today’s context continue among scholars. Here, we will simply address the first two categories in a little more detail.

Technically, the poor and needy are defined as those whose zakatable assets are valued below the nisab level and whose surplus non-zakatable assets are also valued below the nisab level. Surplus assets are defined as any non-zakatable assets that are never used. Someone whose surplus assets are valued above the nisab level, and who also has zakatable assets valued below the nisab level, does not pay or receive zakat.

The distinction between the poor and the needy is typically that the former represents absolute poverty (i.e. absence of food, clothing, shelter) and the latter represents a sense of relative poverty (i.e. necessities of life are in place but a person still struggles with some essentials on a regular basis).

When should it be distributed?

Zakat should be distributed within a lunar year of being calculated. If one is giving zakat to a charity or organisation, then its policies should be reviewed to ensure that zakat distribution is taking place on an annual cycle.

Where should it be distributed?

One of the core principles of zakat is for it to be distributed in the area in which it is collected. The socio-economic impact of zakat and the binding effect between the haves and the have-nots are supposed to occur within localities and communities in which funds are collected.

Due consideration must also be given to areas of extreme poverty and/or difficulty as a result of conflict or natural disaster, as well as to relatives who may be eligible to receive zakat. The latter is considered important as a way of maintaining the ties of kinship but excludes one’s ordinary dependants as well as direct ascendants and descendants.

How should it be distributed?

Zakat should be distributed through the most appropriate method that meets the needs of recipients, as well as being practical, impactful and honouring the trust of zakat payers. Methodologies may vary between communities and situations, but the key to zakat distribution is the empowerment of the beneficiary and ultimate transformation from a payer to a recipient.

Iqbal Nasim has been at the helm of the National Zakat Foundation (www.nzf.org.uk) since November 2011. Prior to this, he worked for over five years in the investment banking industry as an equity research analyst in London. He is currently studying for an MSc in Voluntary Sector Management at Cass Business School and holds an MA in Economics and Management from Cambridge University.

Iqbal is passionate about unleashing the potential of Zakat in empowering individuals and societies across the world. He believes Zakat is not just about poverty alleviation, but that it can be integral to the development of a community at every level.

He has spoken about Zakat and NZF extensively across the UK and also at an international level. In 2011, he spoke on the topic of Zakat at the Global Donors Forum, convened by the World Congress of Muslim Philanthropists in Washington DC, and conducted the Zakat Masterclass at the 10th World Islamic Economic Forum in Dubai.

SHARIA-COMPLIANT ESTATE DISTRIBUTION AND ISLAMIC WILLS BY HAROON RASHID

Historical context

Islam is regarded as a complete way of life. This extends to rules relating to the distribution of an estate following death. This is an important consideration in the wider context of Islamic finance, as Muslims will often be looking for professional advice in relation to financial planning at the same time as dealing with affairs relating to their will and the inheritance of their estate.

In many Muslim jurisdictions the law relating to the distribution of estates is based upon the Islamic rules set out in the Qur’an and Sunnah. In all jurisdictions that do not adhere to Islamic principles it is therefore necessary for the individual to plan and ensure that their estate is distributed in accordance with their faith. The importance of Islamic inheritance can be illustrated by a saying of the Prophet:

Any Muslim who has anything to will should not let two nights pass without writing a Will about it.

(Imam Bukhari)

Although this saying of the Prophet is categorised as being advisory by scholars, it is particularly pertinent in non-Muslim jurisdictions as the will can be used to ensure the estate is distributed in the correct Islamic manner. This part of the chapter will deal with some of the key issues that need to be considered by a practitioner advising a Muslim client. It is important to have a grasp of these issues, even when not directly advising in relation to wills, in order to ensure that the key issues are identified and clients are directed correctly.

Waqfs (permanent endowments)

Historically the Islamic inheritance rules have provided for substantial good within Muslim society. It is worth noting that prior to the revelation of inheritance rules, women had no share in the estates of their close relatives – all assets would pass to male relatives and generally to the eldest son. As a result of the Islamic inheritance rules, women received a guaranteed share in the estate from all their closest relatives for the first time, something which was unthinkable in much of the world, even within the last century.

An additional, much overlooked benefit of the rules of inheritance was in the widespread establishment of waqfs. A waqf can be equated to a modern-day trust, the essential elements being that an asset leaves the ownership of the waqif or settlor and enters into the possession of muttawallis or trustees, whose responsibility it is to manage the trust in accordance with the wishes of the waqif. Because Islamic inheritance rules provide that one-third of the estate can pass to charity, there is wide utilisation of this provision, such that at its height waqfs accounted for a huge proportion of public buildings and utilities such as roads, hospitals, schools and shelters for the needy. The whole system of waqf was managed by central government and registers were kept of all waqf property, such that there are still examples of waqf property that was settled nearly 1,000 years ago being utilised for its original purpose.

Waqfs can also be established in one’s lifetime and can provide useful opportunities for tax planning and asset-protection purposes.

Forced Heirship and Testamentary Freedom

Inheritance systems around the world generally fall in between two polar categories: forced heirship versus complete testamentary freedom. The two regimes have conflicting policy considerations and these can be summarised as follows.

Forced heirship

A forced heirship regime is one where the distribution of a deceased’s estate is not within the individual’s control but rather is decided by government or the law of the land. The primary concern in such jurisdictions is to ensure that the surviving family are adequately provided for. In particular, this avoids a situation where a testator is allowed to maliciously disinherit his close family for personal and vindictive reasons or simply because they felt that others would benefit more from their wealth. This model (in part) can be seen in countries such as France and Spain.

Testamentary freedom

The alternative model commonly in use is that testators are given absolute freedom in relation to the distribution of their estate. This is the position in the United Kingdom and the policy consideration at the heart of this decision is that an individual should be able to dispose of his or her wealth as they see fit, and it is not for the government to dictate who or what is the correct distribution for individuals. This does, however, inevitably lead to situations where families have been left in great difficulty as a result of a will, and therefore it is also common that legislation has been enacted that allows a surviving family member or dependant to challenge the will of the deceased (a control on the ‘complete’ testamentary freedom).

The Islamic system

The Islamic system of inheritance of the estate combines elements of both forced heirship and testamentary freedom.

The testamentary freedom element allows a testator freedom to distribute up to one-third of their estate in any manner they see fit, provided they do not benefit the primary inheritors, who must benefit from at least the remaining two-thirds of the estate. This one-third is known as the ‘wasiyyah’ (literally ‘the will’ as this is the only part a Muslim can ‘will’ – the balance is not within their jurisdiction, it is God’s Will). The wasiyyah can be used for charity or to benefit other family, friends or relatives, or anyone who does not benefit from the two-thirds.

At least the remaining two-thirds (it can be more if the one-third is not used in full) represents the forced heirship element in that this must pass in accordance with the Islamic law, which provides a comprehensive system of calculation and distribution of the shares, which will be considered in more detail later in this chapter. Importantly, the surviving spouse, parents and children will usually always benefit from at least two-thirds of the estate, provided they survive the deceased. If one or more of these relatives is not alive at the time then wider family, such as brothers, grandparents, nieces and nephews, etc., may be brought into the distribution.

Therefore the Islamic system ensures that the closest family relatives are provided for as well as allowing the testator freedom over up to one-third of the estate to provide for others who may be in need and/or charitable objects.

Major principles of Islamic inheritance law

An overview of Islamic inheritance

Islamic inheritance is a complex subject, and books have been written about the topic in its own right. There are a few key concepts that are essential for advisers to be aware of when advising clients.

First, they should know there are three main types of inheritors under Islamic law: zawil furood, asabah and zawil arhaam (see Figure 7.4).

Figure 7.4 The three main types of inheritors under Islamic law

Zawil furood

The zawil furood, or the obligatory inheritors, are those inheritors who are mentioned in the Qur’an and Sunnah and they total 12 in number. There are eight female relatives: the wife, mother, grandmother, daughter, granddaughter, full sister, paternal sister and maternal sister. The four male relatives mentioned are the husband, father, paternal grandfather and maternal half-brother.

Although it is not crucial to know all these relations, what is important is to note that the zawil furood are those relations who receive a specified share of the deceased’s estate. From the 12 relations mentioned only the spouse, parents and daughter receive a share of the estate as of right, assuming there are no barriers to inheritance (see later).

Asabah

The asabah are residuary beneficiaries of the deceased and are those relatives who receive the remainder of the estate after the zawil furood, or fixed-share inheritors, have received their proportion. In simple terms this is usually the son(s) of the deceased or, if the deceased does not have a son, then the deceased’s father, failing which his grandfather, brother, paternal uncles and then paternal nephews.

Zawil arhaam

In the vast majority of cases the inheritors will be divided among the zawil furood and the asabah and there will be nothing remaining for the final category of inheritors, the zawil arhaam. This category contains the more distant relatives of the deceased (for example, this includes the maternal grandfather, aunts and sister’s children) and it is sufficient for most circumstances just to know that this category exists.

A basic distribution

As can be gathered from the above, the Islamic system of inheritance is not straightforward and any practitioner looking to fully advise in this area should seek to gain proper training on the full implementation of how the distributions are calculated. However, most clients will have a fairly straightforward distribution, which, given some practice (and utilising the tools mentioned below as checks), can quickly be calculated.

Some rules of thumb to bear in mind are as follows:

- Immediate family will always inherit (assuming no bars on inheritance – see below). This means clients should be advised that their parents, children and spouse are always entitled to receive a share of the estate. The exact proportion will depend on who survives the deceased.

- Where a son survives and parents also survive, the mother’s and father’s shares will always be 1/6th each.

- Where the deceased leaves behind a husband, the husband will receive either 1/2 or 1/4th of the estate. If the deceased was survived by a child then the husband will receive 1/4th, otherwise he will receive 1/2. (It should be noted it is whether the deceased had a surviving child or not that is the key question – the child does not necessarily have to be the surviving spouse’s child as well.)

- Similarly, where the deceased leaves behind a wife, the wife will receive either 1/4th or 1/8th of the estate. If the deceased was survived by a child then the wife will receive 1/8th, otherwise she will receive 1/4th.

- Where a son or sons alone (or together with daughter(s)) survive the deceased, the children as a whole will receive the balance of the estate (in accordance with point 6 below) after the parents and spouse have been allocated their respective shares.

- Where sons and daughters survive the deceased, each son will receive twice the share of each daughter. As an example, where the deceased is inherited by two sons and three daughters, each son will receive a 2/7ths share of the amount passing to the children as a whole and each daughter will receive a 1/7th share.

Example

You meet with a new client in relation to tax planning and sharia-compliance advice. She confirms that her close family is as follows:

- Husband.

- Mother.

- Father.

- Two daughters and one son.

- Three brothers.

Applying the rules above, you can advise that the current distribution of her estate in accordance with sharia law is as follows:

- Her brothers will not inherit as she is survived by a son.

- Her husband, parents and children are all entitled to a share of her estate.

- As she has a son, her parents will each receive 1/6th (or 4/24ths each) of her estate.

- As she has children, her husband will receive 1/4th (or 6/24ths) of her estate.

- The children will receive the balance of the estate, 10/24ths. This will be divided into four equal shares and each daughter will be entitled to one of these shares, with her son receiving the remaining two shares.

Ten key issues

There are some key issues that occur on a regular basis and it is therefore important that advisers have the background to these. Although you may not be preparing the will or advising directly in this regard, it is important to be able to pass this information on to a specialist in the preparation of Islamic wills for them to advise you accordingly. A summary of the key issues is provided below.

1. Funeral expenses

The deceased’s estate is primarily responsible for funeral expenses and this is the first expense that must be deducted from the estate before any of the inheritors can be given their share or any other liabilities can be satisfied. In the majority of cases the deceased’s family will cover the expense; however, Islamically there is no obligation that they do so, and therefore this can be claimed back as part of their share of the estate as appropriate.

2. Debts

Islamically, an individual is responsible for all debts that he or she has accrued during their lifetime and there is strong encouragement for individuals to ensure debts are paid as soon as possible. Where this has not been possible during one’s lifetime, the debts must be cleared from the estate even if this exhausts all funds. The payment of liabilities will obviously be a matter that is also considered during the estate administration under the law of the appropriate jurisdiction, and therefore advice should be taken from a suitably qualified probate lawyer in this regard, particularly when dealing with insolvent estates.

3. Wasiyyah

As mentioned above, Islamic inheritance law incorporates elements of both forced heirship and testamentary freedom. An individual has freedom to ‘will’ up to one-third of his estate to any beneficiaries who do not automatically inherit. Quite often this is used to benefit charity and may also be used in conjunction with other tax-planning options to reduce any estate duty/inheritance tax that may be payable by the estate.

4. Non-Muslims as inheritors

Where the deceased has a non-Muslim relative(s) who would otherwise inherit, Islamic inheritance law states that they will not inherit as of right. (The deceased can, however, leave a share of the estate to them from the wasiyyah.)

5. Male versus female shares

In some cases, but not all, where a male and female relative of the same relation (such as sons and daughters) inherit together, the male will be entitled to twice the share of the female. By way of example, if there are two sons and one daughter of the deceased then the share passing to the children will be divided into five equal shares, and each son will be entitled to 2/5ths and the daughter will receive the remaining 1/5th.

This, however, is not always the case and quite often male and female relatives will inherit equally, such as the mother and father of the deceased inheriting equally when the deceased leaves a son. There are also a number of scenarios where a female of the same degree inherits more than her male equivalent heir. For example, where a deceased leaves behind a mother, a father, a husband and two sons, each son is entitled to 5/24ths of the estate. In exactly the same scenario, but this time where there are two daughters instead of two sons, each daughter receives 4/15ths or approximately 6 per cent more each of the estate than if the deceased had left two sons.

Islamic scholars have commented on some of the wisdoms behind the difference in shares received by male and female heirs of the same degree. Sharia law operates on the maxim of equity. In relation to inheritance, this means that where individuals have received a greater share of inheritance, such as in the case of a son over a daughter, the son has at the same time been given greater responsibilities for the maintenance of his family. The daughter, however, has no such responsibilities and is free to utilise her inheritance in any way she sees fit. As an example, if a brother and sister have both received inheritance from a deceased father, it is the brother’s responsibility to maintain his sister if she is unmarried and has no adult son (who would first be responsible). This system therefore ensures an equilibrium is established between rights and responsibilities of individuals in society.

6. Pensions

Unlike other assets, pension death benefits do not usually form part of the estate for sharia purposes, provided the individual has no right to encash the pension death benefit during their lifetime. In such cases any pension lump sum or continuing payments can be allocated to an individual or multiple individuals as the testator sees fit. Where such pensions are available this can often be used to provide greater financial security for the surviving spouse of the deceased.

7. Life policies

Life insurance is generally considered to be impermissible for Muslims (see Chapter 8 on Islamic Insurance – Takaful). However, where a life policy has been taken out, a testator can be advised that the proceeds of such a policy may in certain circumstances be utilised to pay the estate duty/inheritance tax that the estate is liable for, it being incumbent that the balance of any life policy proceeds be given to charity. There are differences of opinion on this issue among scholars and therefore clients should be advised to take appropriate advice considering their individual circumstances. The life insurance is regarded as ‘the lesser of two evils’ compared with taking the rights of the rightful heirs.

8. Charity and obligations

Muslims are obligated to complete certain acts such as daily prayers, zakat, fasting and pilgrimage. Where some or all of these obligations have not been fulfilled, clients should be advised that they can utilise their wasiyyah to make payments to charity as a recompense.

9. Non-inheritors

As a rule, adopted, illegitimate and stepchildren do not inherit as of right from the deceased, although again these inheritors can receive a share from the wasiyyah.

10. Different schools of thought

For Sunni Muslims there are four main schools of thought. Helpfully, however, there is a consensus among them in practically all common family scenarios.

There are a number of inheritance tools that can be utilised to ascertain the distribution of the deceased’s estate or the potential distribution. These include:

- I Will Solicitors app (available on mobile devices).

- IRTH calculator – this is software designed to calculate the inheritance due to the various inheritors as defined by Islamic law. (www.islamicsoftware.org/irth/irth.html)

Haroon Rashid is perhaps the leading specialist on Islamic Wills in the UK. He has worked as a solicitor for some of the top law firms in the country and also lectures on Wills and probate matters. Currently in the process of writing a book on Islamic Wills he qualified as a lawyer in 2000. In 2003 he wrote his own Islamic Will in what was perhaps the beginning of professionally drafted Islamic Wills in England and Wales. In 2007 he founded I Will Solicitors, the first and perhaps still the only firm in the country that solely specialises in Islamic Wills, Haroon has overseen the preparation of well over 2,000 Wills to date and has lectured up and down the country on the topic of tax efficient Islamic Wills.

ISLAMIC WILLS AND PLANNING

Tax planning

Taxation of estates

Although there are variations around the world, most jurisdictions have some form of estate duty/inheritance tax. The basic principle behind such taxes is that where an individual has passed away with significant assets they should be required to recontribute to wider society, particularly as they have received the benefits during their lifetime. Further, it is generally agreed that the wealthier an individual, and therefore the larger an estate, the more of a tax hit the estate should take (one of the policy objectives effectively being that wealth is redistributed rather than continually being hoarded).

In the United Kingdom, inheritance tax is charged on wealth, usually at the time of death. Inheritance tax applies to estates (and gifts made in the seven years prior to death) exceeding £325,000 (as at 2014/15). Above the threshold of £325,000 inheritance tax is chargeable at 40 per cent. Therefore, in simple terms, an estate of £425,000 will be liable to tax on £100,000 at 40 per cent, resulting in a tax bill of £40,000 (all else remaining equal).

Tax-planning opportunities for Muslim clients

It can be seen from the above that it is important that practitioners and advisers are aware of the tax implications for their clients when advising about wills and Islamic finance products generally. This can be particularly pertinent for Muslim clients, as shown in the examples below.

Example

In the United Kingdom, where a Muslim woman passes away leaving behind a husband, children and parents and an estate worth £6 million, the Islamic distribution would be as follows:

- Husband receives 1/4th of the estate, or £1.5 million.

- Mother receives 1/6th of the estate, or £1 million.

- Father receives 1/6th of the estate, or £1 million.

- Children receive the balance of the estate, or £2.5 million.

In the United Kingdom, taxation on the estate, in simple terms, would be worked out as follows:

- Estate is £6 million.

- Deduct share passing to surviving spouse* – £1.5 million.

- Deduct non-taxable portion of the estate – £325,000.

- Balance £4,175,000.

- This is taxed at 40 per cent, equating to tax of £1,670,000.

*This is considered to be free of tax.

There are various tax-planning measures that clients in similar situations should be advised about: this will obviously vary significantly between jurisdictions and therefore advisers will need to take different measures in different jurisdictions. Some of these measures are considered in more detail below.

Life interest trust will

UK legislation provides that all assets passing between spouses pass free of tax (provided that certain domicile rules are met) – this is known as spouse exemption. Additionally, the spouse exemption is available where one spouse leaves their entire estate into a trust fund whereby the surviving spouse is entitled to the income from that trust. In the United Kingdom, such trusts are known as life interest trusts, where the spouse is a life tenant (the one entitled to the income). It is important to note that although the surviving spouse has a right to the income, the trustees of the trust have discretion to appoint capital to any beneficiary.

The use of a life interest trust will with the surviving spouse as a life tenant in a will for wealthy Muslim clients can ensure significant inheritance tax or estate duty savings, and this is best illustrated by looking again at our example above.

Example

Where the same Muslim woman passes away leaving behind husband, children and parents and a £6 million estate, but having a life interest trust will with the surviving husband as the life tenant, the tax position is significantly improved.

In the United Kingdom, the taxation on the estate would be calculated as follows:

- Estate is £6 million.

- Entire estate is deemed to pass to spouse – £6 million.

- Balance £0.

- Resulting in tax saving on first death of £1.67 million.

As this example shows, the entire estate is treated as being that of the surviving husband, although he is entitled to income only for as long as there are assets within the trust. The trustees can distribute, after the death of the wife, the capital to any named beneficiary and where an Islamic will is required, the trustees would invariably distribute the capital to the beneficiaries in the appropriate way. Wills usually have a side letter of wishes requesting that the trustees ensure an Islamic distribution is effected.

As with any tax-planning measures, each jurisdiction must be considered on its own terms to ascertain the most appropriate planning option.

Lifetime giving

Often an appropriate tax-planning strategy, especially for older wealthier clients, would be for them to gift assets outright to their children, to their grandchildren or to charity as appropriate. Islamically, an individual is allowed to make gifts during their lifetime as they please. Generally speaking, gifts to children should be made equally (or according to some views, in accordance with the sharia distribution on death). This can be varied, however, if the individual has good reason to favour one child over another, such as one child being in greater financial need.

Making gifts during one’s lifetime is also a way of reducing the size of an estate for inheritance tax or estate duty purposes. However, advisers should be aware of any provisions within a jurisdiction that limit an individual’s ability to do so for tax-planning purposes. As an example, in the United Kingdom an individual’s estate is considered to be the assets they own at death, together with any gifts over £3,000 that have been made in the seven years preceding death. The aim of this legislation is to avoid a situation where an individual gifts his whole estate to a beneficiary on his deathbed, thus avoiding the tax that would otherwise have been payable. Similarly, in the United Kingdom, where an individual makes a gift but continues to benefit from that gift, this will still be considered to be part of his estate irrespective of how long ago they actually made the gift.

Under Islamic law there is a concept of marawdul maut or deathbed illness. Where an individual is in the final illness that actually leads to his death and is bedridden as a result of this illness, his usual freedom of discretion in relation to gifting is curtailed. The limit of the deathbed illness is one lunar year prior to death. In such a state, where an individual makes a gift to a beneficiary of his estate, this is valid only if the other beneficiaries all agree (all individuals must be adult). Where an individual makes a gift to another beneficiary of his estate, it will be treated as being a part of his wasiyyah and therefore only a maximum of one-third of the estate value can be given. Appropriate advice should always be sought in situations where an individual is in his final illness.

Lifetime trusts (waqfs)

Rather than making an outright gift to an individual a client may prefer to retain control of the asset. In such circumstances a waqf or trust would be an appropriate vehicle in which to provide for tax planning as well as allowing the client to retain control of the asset as trustee. Provided that the trustee could no longer benefit from the asset, and the control of the asset is not solely in the hands of the person making the gift, it is likely to be deemed valid for Islamic law purposes as well as in the jurisdiction in which the asset is gifted into trust.

Protecting assets for beneficiaries

By making a gift into a trust a client can obtain another benefit, in that the asset can be protected for the use of a vulnerable beneficiary. Trusts are an excellent vehicle where a beneficiary is young, elderly or mentally or physically disabled. The trustees appointed to the trust can utilise the assets of the trust and invest the same for the benefit of the vulnerable beneficiary. Advisers should be able to identify situations in which a trust fund would be appropriate and advise clients accordingly.

The Islamic law of inheritance is a complex subject and practitioners, when advising on the same, will need to be aware of the local jurisdiction and any conflict with the Islamic position, as well as having a thorough understanding of the Islamic law of inheritance.

CONCLUSION

This chapter has looked at three very important topics:

- sharia-compliant investments;

- the obligatory duty to give a proportion of one’s wealth to charity (zakat);

- sharia-compliant estate distribution and Islamic wills.

All these areas have a profound impact on how Muslims manage their wealth and as this chapter has shown, there is a set of principles and a framework that have developed for each of these areas.

At the very least it is useful for practitioners to have an appreciation of these areas. In particular, asset managers interacting with the Islamic space need to know about sharia-compliant asset classes and the criteria used to determine sharia compliance. Lawyers and other professionals advising Muslims on estate planning, wills and inheritance tax need to have a working knowledge of Islamic inheritance laws. Wealth managers need to know about all three of these areas to advise their Muslim clients on effective wealth-management strategies that ensure wealth is earned in a permissible way, the obligatory duty to give to charity is factored into the annual planning, and an estate plan is in place that is sharia-compliant and tax-efficient.

1 Thomson Reuters, ‘Global Asset Management Report 2014’.

2 Thomson Reuters, ‘Global Asset Management Report 2014’.

3 Thomson Reuters, ‘Global Islamic Asset Management Report 2014’.

4 January 2014 factsheet.

5 Investment Memorandum for investment into London Central Apartments II Limited, 5 February 2014.