1

Deploying Ubuntu Server

Ubuntu Server is an extremely powerful distribution of Linux for servers and network appliances. Whether you’re setting up a high-end database or a small office file server, the flexible nature of Ubuntu Server will meet and surpass your needs. In this book, we’ll walk through all the common use cases to help you get the most out of this exciting platform. Ubuntu Server features a perfect mix of modern development frameworks and rock-solid stability, and its hardware support enables it to be installed on the latest server hardware.

In this chapter, I’ll guide you through the process of deploying Ubuntu Server from start to finish. We’ll begin with some discussion of best practices, and then we’ll obtain the software and create our installation media. Next, I’ll give you a step-by-step rundown of the entire installation procedure. By the end of this chapter, you’ll have an Ubuntu Server installation of your own to use throughout the remainder of this book. In addition, since Canonical (the makers of Ubuntu) now offers official support for Raspberry Pi, we’ll look at the process of setting that up as well.

In this chapter, we will cover:

- Technical requirements

- Determining your server’s role

- Choosing a device for our server

- Obtaining installation media

- Creating a bootable flash drive

- Installing Ubuntu Server

- Installing Ubuntu Server on a Raspberry Pi

To get started, we’ll first take a look at some of the technical requirements for deploying a server with Ubuntu.

Technical requirements

To follow along with the examples in this book, you’ll need an Ubuntu Server installation to work with. In general, the following specifications are the estimated minimums to successfully install Ubuntu Server:

- 64-bit CPU

- 1 GB RAM

- 10-GB hard disk (16 GB or more is recommended)

64-bit CPU support is now a requirement, with the only exception being the Raspberry Pi version. This is because Canonical no longer makes versions of Ubuntu available for 32-bit PC and server processors. While this may seem like a downside, all computers sold today support 64-bit operating systems, and consumer CPUs have been 64-bit capable since at least 2003. Even if you have an older PC lying around that you don’t think is capable of running a 64-bit operating system, you’d be surprised—even the later models of the Pentium IV (which is quite old) support this, so this requirement shouldn’t be hard to meet. Don’t worry about the particulars of this right now, we’ll go through the requirements in more detail later on in this chapter.

Now that we understand the technical requirements of Ubuntu Server, let’s consider the role our server will play in our organization.

Determining your server’s role

You’re excited to set up an Ubuntu Server installation so you can follow along with the examples contained in this book. It is also important to understand how a typical server rollout is performed in the real world. Every server must have a purpose, or role. This role could be that of a database server, web server, file server, and so on. In a nutshell, the role is the value the server adds to you or your organization. Sometimes, servers may be implemented solely for the purpose of testing experimental code. And this is important too—having a test environment is a very common (and worthwhile) practice.

Once you understand the role your server plays within your organization, you can plan for its implementation. Is the system mission critical? How would it affect your organization if for some reason this server malfunctioned? Depending on the answer to this question, you may only need to set up a single server for this task, or you may wish to plan for redundancy such that the server doesn’t become a central point of failure. An example of this may be a DNS server, which would affect your colleagues’ ability to resolve local hostnames and access required resources. It may make sense to add a second DNS server to take over in the event that the primary server becomes unavailable for some reason.

Another item to consider is how confidential the data residing on a server is going to be for your environment. This directly relates to the installation procedure we’re about to perform, because you will be asked whether or not you’d like to utilize encryption. The encryption that Ubuntu Server offers during installation is known as encryption at rest, which refers to the data stored within the internal storage volumes on that server. If your server is destined to store confidential data (accounting information, credit card numbers, employee or client records, and so on), you may want to consider making use of this option.

Encrypting your hard disks is a really good idea to prevent miscreants with local access from stealing data. As long as the attacker doesn’t have your encryption key, they cannot steal this confidential information. However, it’s worth mentioning that anyone with physical access can easily destroy data (encrypted or not), so remember to keep your server room locked!

At this point in the book, I’m definitely not asking you to create a detailed implementation diagram or anything like that, but instead to keep in mind some concepts that should always be part of the conversation when setting up a new server. It needs to have a reason to exist, it should be understood how critical and confidential the server’s data will be, and the server should then be set up accordingly. Once you practice these concepts as well as the installation procedure, you can make up your own server roll-out plan to use within your organization going forward. All in all, understanding the purpose of each component in your infrastructure is a great mindset to adopt.

At this point, we now understand how we might identify a role for our server and how it will fit into our organization. In the next section, we’ll take a look at the process of actually installing Ubuntu Server, so we will have at least one test machine to use for the examples in this book.

Choosing a device for our server

I bet you’re excited to set up your very own installation of Ubuntu Server and dive in. But before we can do that, we have to decide what to actually install it on. For the purposes of this book, there isn’t a specific requirement in terms of hardware. You just need an Ubuntu Server installation of some sort, and it wouldn’t hurt to set up multiple servers if you can—you don’t need them all to be on the same device type. Having multiple servers will help you experiment with networking when we get to that point later on in the book. But for now, it’s only a matter of utilizing whatever you have at your disposal to get an Ubuntu installation going.

In particular, the following list includes the most common devices you can consider for your Ubuntu Server installation:

- Physical server

- Physical desktop

- Laptop

- Virtual machine

- Virtual private server

- Raspberry Pi

Let’s take a look at each of these options in more detail.

Physical server

Nowadays, it’s very easy to find used physical servers for an affordable price. Dell PowerEdge is a very common model, and the R610 and R710 specifically are good choices that are readily available second. These servers are commonly made available in the reseller market after companies upgrade to newer models. The R610 and R710 are a bit old, but their specs are still great for testing purposes. If you’re able to find a newer model (such as the R720) for a reasonable price, even better.

The downside with physical servers is that they take up a lot of room and can often be power-hungry (and noisy). Make sure to shut them down when not in use and look into the cost of electric services in your area—these servers can be very cheap to run or very expensive, depending on your electricity rates.

Physical desktop

If you don’t have access to a physical server, you might consider running Ubuntu Server on a desktop. It’s common for some computer users to hang onto their older PC after upgrading to something new and shiny. So rather than let your old desktop collect dust, why not put it to work? Sure, your older computer may not run today’s high-end games, but that doesn’t matter for our purposes. Ubuntu Server runs very well, even on older hardware. In fact, it’s quite common for home learners to use small form factor PCs, such as the Intel NUC, for this purpose. In addition, using a physical desktop has some advantages over physical servers as well. They often use much less power than server hardware, and they also tend to produce less noise.

When it comes to production servers (installations of Ubuntu Server for use within your organization), desktops are typically not a good pick. Depending on the model, actual server hardware might have additional hardware and features that might not be present with a desktop. For example, true server builds often feature true hardware RAID, Error Correction Code (ECC) memory, multiple processors, and more. Although a desktop tower typically lacks those features, if you install Ubuntu Server on your old PC it’s every bit as valid a server as an actual server chassis would be – though it wouldn’t scale well in a data center. Since we’re just learning though, that doesn’t matter for us for our current use-case.

Laptop

Another option worth considering is to install Ubuntu Server on a laptop. If you have an older laptop lying around that you’re no longer using, it might be a great option for learning Ubuntu Server. If you do decide to use a laptop for this purpose, then the same factors will apply to this as I wrote regarding using a desktop.

However, the reason I decided to give laptops their own section here is because there are some additional benefits with these that you can take advantage of. With a real data center server rack, you’ll typically have access to a Keyboard, Video, and Mouse (KVM). This might mean that you could have a physical monitor, keyboard, and mouse attached to the server, or a special device with all three built in. Servers within data centers will also have an Uninterruptible Power Supply (UPS) that will keep them running for a time, even when your power goes out.

When it comes to a laptop, it has those same features. Laptops have a built-in keyboard, mouse, and display. If the battery that’s installed in the laptop works, then you have a UPS as well. For those reasons, a laptop might even have an advantage over desktops overall.

However, just like desktop computers, laptops aren’t generally acceptable for use in an actual data center. For our use-case though, we only need one or more installations of Ubuntu Server for going through the examples in this book. And for that purpose, dedicating any computers you’re not currently using would be more than adequate.

Virtual machine

If you don’t have access to a physical machine, you might consider a Virtual Machine (VM). Most computers sold nowadays support the ability to run VMs. VirtualBox is a great solution, as it’s easy to use and available for all of the major operating systems. Just like Ubuntu itself, VirtualBox is available for free, so it’s typically the lowest-cost entry-point for getting started. Also, VirtualBox allows you to easily create snapshots of your Ubuntu installation, so you can create a point-in-time backup before going through an example in this book, and then restore it to repeat tasks as often as you’d like. The ability to utilize snapshots alone makes a VM especially attractive for our needs.

The downside to VirtualBox is that you’ll need to be able to dedicate at least 1 GB of RAM to your Ubuntu Server VM, and your CPU will need to support virtualization extensions, which you’ll need to enable in your computer’s settings if your device supports it.

VirtualBox can be downloaded here: https://www.virtualbox.org.

Virtual private server

Services such as Amazon Web Services, Google Cloud, Linode, Microsoft Azure, Digital Ocean, and others allow you to set up Ubuntu Server in the cloud for you to connect to and manage via OpenSSH. Choosing the Virtual Private Server (VPS) option has some benefits; you don’t need to find room for a large physical server, and you don’t need to worry about power usage either. Another benefit is that you won’t even need to go through the installation process in this chapter at all; the cloud provider will do that for you when you choose to deploy Ubuntu Server on their platform. The main downside, though, is that VPS instances are not free—you’ll need to look at the costs associated with running Ubuntu on such a server and decide if that cost makes sense. Some VPS services allow you to set up instances for as little as $5 USD per month, which can be lower than the cost of the electricity needed to run a physical server in some areas.

Raspberry Pi

Raspberry Pi units are quickly becoming a user favorite for server use cases. They are inexpensive (some models are available for less than $40 USD) and they also use very minimal electricity—you can leave them powered on 24/7 with a virtually unnoticeable difference in your power bill. In fact, they use about as much power as it takes to charge a high-end cellphone. Another benefit is that a Raspberry Pi is generally going to be more powerful than an entry-level VPS. The cheapest VPS instances typically have just 1 CPU core and 1 GB of RAM, but modern Raspberry Pis are produced with quad-core CPUs, as well as 2 GB, 4 GB, or 8 GB of RAM depending on which model you purchase. This means that a Raspberry Pi can possibly perform better than cheaper VPS instances. The downside to Raspberry Pi is that some applications are unavailable, since they utilize ARM CPUs instead of x86. This means that some examples in this book will not work on a Pi (although the majority will).

Once you’ve chosen a device to install Ubuntu Server on, we can continue. If you chose to utilize a VPS, you can move on to the next chapter, Chapter 2, Managing Users and Permissions, as you won’t need to walk through the installation process. In the case of the Raspberry Pi, if that’s your chosen platform, you can skip to the end of this chapter for a dedicated section about setting that up. For all other devices, continue reading for a walk-through for the Ubuntu Server Live Installer.

Obtaining installation media

It’s time to get started! If you’ve decided to utilize a physical server, desktop, laptop, or VM as your test server, then you’ll need to go through the installation process to set up Ubuntu. Don’t worry—it’s very easy to do and it might even be easier than you’d think, as there are fewer overall steps in the process when compared to older versions. If you’ve instead opted to use a VPS or Raspberry Pi, you won’t need to go through this process, as VPS providers do this for you and Raspberry Pi has a different setup method altogether (we’ll cover this later in the chapter, in the Installing Ubuntu on a Raspberry Pi section).

Assuming that you’ve decided to use a device that does require going through the installer, we’ll need to download Ubuntu Server and then create bootable installation media to install it. How you do this largely depends on your hardware. Does your device have an optical drive? Is it able to boot from USB? Refer to the documentation for your device to find out.

It’s recommended to utilize a flash drive for the installation if you can, preferably one that uses USB 3.0 or higher since you’d benefit from its faster speed compared to USB 2.0. The reason for the preference for using a flash drive is due to the fact that they are typically faster than a DVD.

However, if your device is older, you won’t have a choice, as legacy devices are not able to boot from USB at all. As a general rule, use a flash drive if you can and opt for a DVD only if you have no choice.

In the past, Ubuntu Server ISO images could be used to create either a bootable CD or DVD. Nowadays, writable CDs don’t have enough space to support the download size. Therefore, if you choose to burn to bootable optical media, you’ll need a writable DVD at a minimum.

Unfortunately, the differing age of servers within a typical data center introduces some unpredictability when it comes to how to boot installation media. When I first started with servers, it was commonplace for all standard rack servers to contain a 3.5-inch floppy disk drive, and some of the better ones even contained an optical drive. Nowadays, servers typically contain neither. If a server does have an optical drive, it could potentially go unused for an extended period of time and become faulty without anyone knowing until the next time someone goes to use it. Some servers boot from USB, others don’t. To continue, check the documentation for your hardware and plan accordingly. Your server’s capabilities will determine which kind of media you’ll need to create.

Regardless of whether we plan on creating a bootable USB or DVD, we only need to download a single file. Navigate to the following site in your web browser to get started: https://www.ubuntu.com/download/server.

From this page, we’re going to download Ubuntu 22.04 LTS by clicking on the Option 2 – Manual server installation button:

Figure 1.1: Ubuntu Server 22.04 download page

Next, you’ll be offered one or more versions of Ubuntu Server for download:

Figure 1.2: Revealing Ubuntu Server 22.04 download options

As of the time this chapter was being written, Ubuntu Server 22.04 is the latest version, and is shown as the primary download option. There may be other versions of Ubuntu Server listed on this page, such as 22.10 and 23.04, depending on when you’re reading this. New releases of Ubuntu are published every six months. However, this book only covers the Long Term Support (LTS) release, due to the fact that it benefits from five years of support.

By comparison, non-LTS versions (or “interim releases”) are only supported for nine months and are therefore not an appropriate choice for production servers. Organizations don’t typically utilize non-LTS releases at all, except for testing upcoming features prior to general availability, so for our purposes, we’ll stick with the LTS version. Once the download is completed, we’ll end up with an ISO image we can use to create our bootable installation media.

If you’re setting up a VM, then the ISO file you download from the Ubuntu downloads page will be all you need; you won’t need to create a bootable DVD or flash drive. In that scenario, all you should need to do is create a VM, attach the ISO to the virtual optical drive, and boot it. From there, the installer should start, and you can proceed with the installation procedure outlined later in this chapter, in the Installing Ubuntu Server section. Going over the process of booting an ISO image on a VM differs from one virtualization solution to another, so detailing the process with each would be a very difficult task. Thankfully, the process is usually straightforward and you can find the details within the documentation of your hypervisor. In most cases, the process is as simple as attaching the downloaded ISO image to the VM and then starting it up.

If your device does not support booting from USB and you find yourself needing to create a bootable DVD, the process is typically just a matter of downloading the ISO file and then right-clicking on it. In the right-click menu of your operating system, you should have an option to burn to disk or some similar verbiage. This is true of Windows, as well as most graphical desktop environments of Linux where a disk-burning application is installed.

The exact procedure differs from system to system, mainly because there is a vast amount of software combinations at play here. For example, I’ve seen many Windows systems where the right-click option to burn a DVD was removed by an installed CD/DVD-burning application. In that case, you’d have to first open your CD/DVD-burning application and find the option to create media from a downloaded ISO file. As much as I would love to outline the complete process here, no two Windows PCs typically ship with the same CD/DVD-burning application. The best rule of thumb is to try right-clicking on the file to see whether the option is there, and, if not, refer to the documentation for your application. Keep in mind that a data disk is not what you want, so make sure to look for the option to create media from an ISO image or your disk will be useless for our purpose.

At this point, you should have an Ubuntu Server ISO image file downloaded. If you are planning on using a DVD to install Ubuntu, you should have that created as well. In the next section, I’ll outline the process of creating a bootable flash drive that can be used to install Ubuntu Server.

Creating a bootable flash drive

The process of creating a bootable USB flash drive with which to install Ubuntu used to vary greatly between platforms. The steps were very different depending on whether your workstation or laptop was currently running Linux, Windows, or macOS. Thankfully, a much simpler method has come about. Nowadays, I recommend the use of Etcher to create your bootable media. Etcher is fantastic in that it abstracts the method such that it is the same regardless of which operating system you use, and it distills the process to its most simple form.

Another feature I like is that Etcher is safe; it prevents you from destroying your current operating system in the process of mastering your bootable media. In the past, you’d use tools like the dd command on Linux to write an ISO file to a flash drive. However, if you set up the dd command incorrectly, you could effectively write the ISO file over your current operating system and wipe your entire hard drive. Etcher doesn’t let you do that.

Before continuing, you’ll need a USB flash drive that is either empty or one you don’t mind wiping. This process will completely erase its contents, so make sure the device doesn’t have information on it that you might need. The flash drive should be at least 2 GB or larger. Considering it’s difficult to find a flash drive for sale with less than 4 GB of space nowadays, this should be relatively easy to obtain.

To get started, head on over to https://www.balena.io/etcher/, download the latest version of the application from their site, and open it up. The window will look similar to the following screenshot once it launches:

Figure 1.3: Utilizing Etcher to create a bootable flash drive

At this point, click Flash from file, which will open up a new window that will allow you to select the ISO file you downloaded earlier. Once you select the ISO, click on Open:

Figure 1.4: Selecting an ISO image with Etcher

If your flash drive is already inserted into the computer, Etcher should automatically detect it. In the event that you have more than one flash drive attached, or Etcher selects the wrong one, you can click Change and select the flash drive you wish to use:

Figure 1.5: Selecting a different flash drive with Etcher

Finally, click Continue to get the process started. At this point, the flash drive will be converted into Ubuntu Server installation media that can then be used to start the installation process:

Figure 1.6: Etcher in the process of writing a flash drive

After a few minutes (the length of time varies depending on your hardware), the Flashing process will complete, and you’ll be able to continue and get some installations going. Before we get into that, though, we should have a quick discussion regarding partitioning.

Planning the partitioning layout

Partitioning your disk allows you to divide up your hard disk to dedicate specific storage allocations to individual applications or purposes. For example, you can dedicate a partition for the files that are shared by your Apache web server so changes to other partitions won’t affect it. You can even dedicate a partition for your network file shares—the possibilities are endless. Each partition is mounted (attached) to a specific directory, and any files sent to that directory are thereby sent to that separate partition. The names you create for the directories where your partitions are mounted are arbitrary; it really doesn’t matter what you call them. The flexible nature of storage on Linux systems allows you to be creative with your partitioning as well as your directory naming, since the Linux filesystem gives you more flexibility when it comes to mounting storage devices in specific folders.

Admittedly, we’re getting ahead of ourselves here. After all, we’re only just getting started and the point of this chapter is to help you set up a basic Ubuntu Server installation to serve as the foundation for the rest of the chapter. When going through the installation process, we’ll accept the defaults anyway. However, the goal of this section is to give you examples of the options you have for consideration later. At some point, you may want to get creative and play around with the partition layout.

With custom partitioning, you’re able to do some very clever things. For example, with the right configuration, you’ll be able to wipe and reload your distribution while preserving user data, logs, and more. This works because Ubuntu Server allows you to carve up your storage any way you want during installation. If you already have a partition with data on it, you can choose to leave it as is so you can carry it forward into a new install. You simply set the directory path where it’s mounted to be the same as before, restore your configuration files, and your applications will continue working as if nothing happened.

One very common example of custom partitioning in the real world is separating the /home directory into its own partition. Since this is where users typically store their files, you can set up your server such that a reload of the distribution won’t disturb their files. When they log in after a server refresh, all their files will be right where they left them. You could even place the files shared by your Apache web server on to their own partition and preserve those too. You can get very creative here.

It probably goes without saying, but when reinstalling Ubuntu, you should back up partitions that have data you don’t want to be wiped (even if you don’t plan on formatting the partitions). The reason being, one wrong move (literally a single checkbox) and you can easily wipe out all the data on that partition. Always back up your data when refreshing a server.

Another reason to utilize separate partitions may be to simply create boundaries or restrictions. If you have an application running on your server that is prone to filling up large amounts of storage, you can point that application to its own partition, limited by size. An example of where this could be useful is an application’s log files. Log files are the bane of any system administrator’s life when it comes to storage.

While helpful if you’re trying to figure out why something crashed, logs can fill up a hard disk very quickly if you’re not careful. In my experience, servers have been known to come to a screeching halt due to log files filling up all the available free space on a server where everything was on a single partition. The only boundary the application had was the entirety of the disk itself.

While there are certainly better ways of handling excessive logging (log rotating, disk quotas, and so on), a separate partition would certainly help. If the application’s log directory was on its own partition, it would be able to fill up that partition, but not the entire drive, which would cause issues but wouldn’t affect the entire server. As an administrator, it’s up to you to weigh the pros and the cons of these strategies to avoid server overload and develop a partitioning scheme that will best serve the needs of your organization.

Success when maintaining a server is a matter of efficiently managing resources, users, and security—a good partitioning scheme is certainly part of that. Sometimes it’s just a matter of making things easier on yourself so that you have less work to do should you need to reload your operating system. For the sake of following along with this book, it really doesn’t matter how you install or partition Ubuntu Server. The trick is simply to get it installed—you can always practice partitioning later. After all, part of learning is setting up a platform, observing any issues that may occur, and then fixing it up.

Here are some basic tips regarding partitioning:

- At a minimum, a partition for the root filesystem (designated by a forward slash) is required.

- The

/vardirectory contains most log files and is therefore a good candidate for separation for the reasons mentioned previously in this section. - The

/homedirectory stores all user files. Separating this into a separate partition can be beneficial as it gives you the possibility of having your user files survive a reinstall of Ubuntu. - If you’ve used Linux before, you may be familiar with the concept of a swap partition, which is a special partition that can act as RAM when your memory becomes full. This is no longer necessary—a swap file will be created automatically in newer Ubuntu releases.

When we perform our installation in the next section, we’ll choose the defaults for the partitioning scheme to get you started quickly. However, I recommend you come back to the installation process at some point in the future and experiment with it. You may come up with some clever ways to split up your storage. However, you don’t have to—having everything in one partition is fine too, depending on your needs.

Now that we have an understanding of what partitioning is, we should have all of the essential topics covered to enable us to actually get the installation of Ubuntu Server going. Let’s go ahead and work on that now.

Installing Ubuntu Server

At this point, we should be ready to get an installation of Ubuntu Server going. In the steps that follow, I’ll walk you through the process.

To get started, all you should need to do is insert the installation media into your server or device and follow the onscreen instructions to open the boot menu. The key you press at the beginning of the POST process differs from one machine to another, but it’s quite often F10, F11, or F12. Refer to your documentation if you are unsure, though most computers and servers tell you which key to press at the beginning. You may miss this window of opportunity the first few times, and that’s fine—to this day I still seem to need to restart the machine once or twice to hit the key in time.

Once you successfully boot your device while using your Ubuntu Server installation media, navigating the installer is relatively straightforward. You simply use the arrow keys to move up and down to select different options, and press Enter to confirm choices. The Esc key will allow you to exit from a sub-menu. Moving around within the installer is pretty easy once you get the hang of it.

Once the installer starts, you’ll see the first of many selection screens. The first option, Ubuntu Server, allows you to start the Ubuntu Server installer. The second option, Test memory, runs a special program that helps you determine if you have any physical defects with the RAM modules installed inside your device. I always recommend testing the memory of your device once per year at least, and especially before you install an operating system for the first time. Memory issues can be rare, but you’d be surprised. It might be a good idea to test your memory just to be safe.

If you wish to test the memory of your device, you can go ahead and do so. In order to move on though, we’ll need to choose the Ubuntu Server option in order to start the installer:

Figure 1.7: The initial boot screen for the Ubuntu Server installation media

Next, you’ll see a screen allowing you to select your language as in the following screenshot:

Figure 1.8: Language selection at the beginning of the installation process

If your language is anything other than English, you’ll be able to select that here. Once you’re satisfied with the chosen keyboard layout, you continue by selecting Done at the bottom of the screen.

After choosing your language, you’ll be brought to a screen that enables you to set your Keyboard configuration. If the proper keyboard layout wasn’t automatically selected, you can change it here.

Figure 1.9: Setting the layout of your keyboard

Next, we’ll see an option to install Ubuntu Server, or Ubuntu Server (minimized). For this, we’ll choose the first option. Choosing to install a minimized version of Ubuntu Server might be a good fit for creating smaller installations, however for this book, we’re going to focus on the normal installation type.

Figure 1.10: Choosing your installation type

Next, the Ubuntu Server installer will attempt to automatically detect the appropriate parameters for your network card. By default, it should detect the appropriate settings via Dynamic Host Control Protocol (DHCP). We’ll go over DHCP in a future chapter, specifically Chapter 11, Setting Up Network Services. For now, the defaults should be fine. Select Done to continue.

Figure 1.11: Network configuration within the Ubuntu Server installer

Continuing, the next screen will give us an opportunity to set a proxy address if we need one. Most readers shouldn’t need this, and those that do might’ve been provided particular proxy settings from a network administrator. So for us, we’ll select Done to continue:

Figure 1.12: Proxy settings within the Ubuntu Server installer

On the next screen that appears, we’ll see an option to set a mirror address for our installation. As we’ll discuss further in Chapter 3, Managing Software Packages, this pertains to an online source from which installable applications (packages) can be downloaded. In some cases, an organization might host its own repository for available software.

Therefore, on this screen, you can choose a different server to provide software if you have your own. For our needs, we’ll select Done to accept the default and continue:

Figure 1.13: Mirror settings within the Ubuntu Server installer

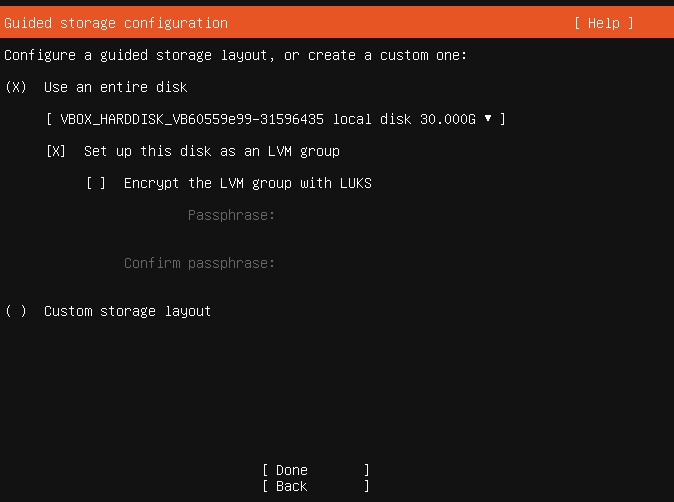

Next, we’ll see settings for storage. In particular, this is where we can configure the hard disk layout for our installation. Earlier in this chapter, I mentioned that it’s common practice to adopt a custom partitioning scheme. If you have a preferred partition layout, this is the screen where you would input those decisions by selecting Custom storage layout.

However, doing so would be jumping ahead of the book a bit, so instead I recommend selecting Done to accept the default, which will take over the entire hard disk:

Figure 1.14: Configuring storage while installing Ubuntu Server

After we inform the installer how to set up the storage device on our server, we’ll next see a screen that summarizes our selections while configuring storage. Since we chose the default layout, we’ll see a basic layout presented on this screen. If you did decide to set up a customized partitioning scheme, you’d want to ensure that the selections shown here match what you had in mind. If you’re confused as to what any of this means, don’t worry too much about it for now. We’ll cover more details surrounding storage in Chapter 9, Managing Storage Volumes. For now, select Done to accept the default storage layout:

Figure 1.15: Storage configuration summary screen while installing Ubuntu Server

If you didn’t already know, this process will erase everything on the hard disk of your device, and replace it with your new Ubuntu Server installation. This means that if you haven’t backed up any important data that might be saved on your device, you will lose that information forever. The screen that comes up next will explain that this is the last step before your disk is wiped and Ubuntu Server is installed. If you’re certain that your disk doesn’t have any important data on it, you can select Continue:

Figure 1.16: Confirming the installation and wiping of the hard disk

When we install Ubuntu Server, it will create an initial user account for us as part of the process. This user will be used for configuring and maintaining the server after installation. In this section of the installer, we’ll be given an opportunity to name this user and create a password.

Fill out your information on this screen, as I have in the following screenshot. One important thing to keep in mind is that the user you create here will have administrative access. You can always create other users later on, but the user you create here will have special privileges. When finished, arrow down to Done and press Enter:

Figure 1.17: Ubuntu Server installer, configuring user details

Next, you’ll see an Install OpenSSH server option. I recommend that you enable this. OpenSSH is the closest thing to a default we have when it comes remotely managing Ubuntu servers, and is discussed in more detail in Chapter 10, Connecting to Networks. For now, let’s enable this option as it will be one less thing for us to do later. To do so, you can press the spacebar while the cursor is on the option to add an asterisk symbol into its checkbox, which signifies a selection. After you do that, select Done to continue:

Figure 1.18: Choosing whether or not to set up OpenSSH while installing Ubuntu Server

Next, we’ll see a selection of some of the more common applications that can be run on Ubuntu Server. For example, we have selections for Nextcloud, Docker, and more on this screen. For now, we’ll ignore these since we’ll be going through the process of manually setting up many services throughout the book. So for now, select Done to continue:

Figure 1.19: Featured application selection

That’s pretty much it—the installer will continue along on its own, as it has all the information it needs from you at this point. Once it’s done, you’ll see a Reboot option at the bottom of the screen; go ahead and select that:

Figure 1.20: Completed installation, pending reboot

At this point, your server will reboot and then Ubuntu Server should start right up. Congratulations! You now have your own Ubuntu Server installation!

In addition to server-specific hardware and virtual machines, Ubuntu Server can also be installed on a Raspberry Pi, and that’s exactly what we’ll take a look at in the next section.

Installing Ubuntu on a Raspberry Pi

The Raspberry Pi platform has become quite a valuable asset in the industry, and a useful server platform. These tiny computers, now with four cores and up to 8 GB of RAM, are extremely power efficient and their performance is good enough that you can actually transform them into actual servers. In my lab, I have several Raspberry Pis on my network, each one responsible for performing specific tasks or functions. In many cases, you wouldn’t even tell that they were devices with lower-powered hardware. Perhaps even more surprising is the fact that the Raspberry Pi 4 can outperform some lower-tier cloud instances, giving you a powerful server without the monthly cost if you don’t need a high-end CPU. All this, in such a small form factor—these devices are smaller than the coaster under your coffee mug!

Ubuntu Server is available for Raspberry Pi models 2, 3, and 4. To get started, all you’ll need to do is visit the official download page for the Raspberry Pi version of Ubuntu, here: https://ubuntu.com/download/raspberry-pi. This will take you to the following screen:

Figure 1.21: The download section for Raspberry Pi on the official Ubuntu website

Once there, you’ll see a listing of multiple versions for the Pi that are available for download. Refer to the preceding screenshot for an example of options that are available, but keep in mind that Ubuntu may redesign their web page at any time. So as a rule of thumb, download the version that matches the type of Raspberry Pi you have, and go with the 64-bit version if it’s available (the Raspberry Pi 2 only has a 32-bit option available).

The download for the Pi versions will come in the form of a compressed image, which can be written directly to an SD card. To get the process going, open up Etcher, which we downloaded in an earlier step. Once Etcher is open, click Flash from file:

Figure 1.22: Etcher, ready for action

Now, choose the file that was downloaded earlier and select Open:

Figure 1.23: Selecting the file to use to write to the SD card

Next, go ahead and insert an SD card into your computer that will become dedicated to Ubuntu Server. Etcher will completely erase the SD card, so make sure you don’t need any of the data that may be on it. If your computer does not have an SD card slot, you can use a USB card reader. If the proper device isn’t selected, you can click Select target to choose the SD card to use, as shown in Figure 1.24. Then click Continue:

Figure 1.24: Choosing an SD card to use with Etcher for the Raspberry Pi

Once you’ve selected both the image file to use and the target SD card, you’re ready to proceed. Click Flash! to begin the process of writing the image:

Figure 1.25: Etcher, ready to start flashing the SD card

Now, Etcher will prepare the target with the source image file. The process can take anywhere from 5 to 15 minutes depending on the speed of your hardware:

Figure 1.26: Etcher in progress

Once Etcher is finished writing to the SD card, you can eject it from your computer and insert it into the Pi, which can be accessed remotely via SSH. When it finishes booting for the first time, you can log in and begin using it as you would any other Ubuntu Server installation (the username and password both default to ubuntu). From there, you can create a new user for yourself, install applications, and experiment.

Summary

In this chapter, we covered a couple of different installation scenarios in great detail. As with most Linux distributions, Ubuntu Server is scalable and able to be installed on a variety of server types. Physical devices, VMs, and even the Raspberry Pi have versions of Ubuntu available. The process of installation was covered step by step, and you should now have an Ubuntu Server instance of your own to configure as you wish. Also in this chapter, we covered determining the role of your server, the process of creating bootable media, and a walkthrough of setting up Ubuntu Server on your server device (as well as on a Raspberry Pi). You’re now on your way to Ubuntu Server mastery!

In the next chapter, we’ll show you how to manage users. You’ll be able to create them, delete them, change them, manage password expiration, and more. We will also cover permissions so that you can determine what your users are allowed to do on your server. See you there!

Relevant tutorials

- Install Ubuntu Server (Video Tutorial) from LearnLinuxTV: https://linux.video/install-ubuntu-server

Join our community on Discord

Join our community’s Discord space for discussions with the author and other readers: