CHAPTER 11

Antitrust

The world of antitrust enforcement has changed dramatically over the past century. It started at the end of the 1800s with the passage of the Sherman Antitrust Act and has moved along a winding path that featured periods of more and less antitrust enforcement. At present, there is relatively little antitrust enforcement compared to periods such as the 1950s and 1960s. Antitrust enforcement declined into the 1970s and became relatively dormant in the 1980s (see Exhibit 11.1).1 In response to criticisms that antitrust was too inactive for the market’s good, some defenders of the antitrust policies at that time asserted that the market was sufficiently competitive and did not need the assistance of the government as it did in the past.

In the 1990s, this changed somewhat. The antitrust enforcement authorities started to pursue their work with somewhat greater vigor. This vigor reached a peak when the Antitrust Division of the Justice Department aggressively pursued Microsoft – one of the most successful companies in American history. This case did not mark a major change in the intensity of antitrust enforcement, but it did show that the Justice Department was supposedly prepared to pursue even very large actions.1 Some years ago, when the second edition of this book came out, the then head of the antitrust division, one Christine Varney, an Obama administration appointee, asserted that antitrust enforcements involving larger actions would become more intense. Her predictions, ones that she should have had some control over, did not come to pass. Nonetheless, she was able to leverage her somewhat uneventful service at the Justice Department to a partnership at the prominent law firm Cravath Swaine and Moore. So, for her personally, the appointment at the justice department was a big success.

EXHIBIT 11.1 Volume of antitrust lawsuits in the United States.

Source: Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts, Washington, DC.

Exhibit 11.1 shows that while concentration has increased in many industries, the number of antitrust actions by the Federal Trade Commission has remained modest and actually declined somewhat since 2016. What is more troubling is the sharp decline in the number of actions initiated by the Justice Department. It is as though, the Justice Department is phasing itself out of the antitrust enforcement business.

The decline in lawsuits by the Justice Department and the relative inactivity by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) may be explained by the regulatory system that is in place. It is common for commissioners and chairs at the FTC to leave the commission and then work at law firms defending companies against regulatory challenges.(*) These individuals may make a modest income working for the government but they make much higher income after they leave the government. The same is true at the Justice Department. It is simply not credible to think that such regulators are not planning their future career moves when they are evaluating transactions and dealing with law firms which could possibly be future employers given them a dramatically higher income in the future. There is simply a great incentive for them to “play nice” and curry favor with such potential future employers.

In one recent merger, the head of its antitrust division at the Justice Department, Makan Delrahim, came under strong criticism for allegedly serving in the role of a deal maker in the 2019 T‐Mobile and Sprint merger.(**) One can only wonder what future employment opportunities Mr. Delrahim may pursue after he leaves the Justice Department. The conflicts inherent in the antitrust regulatory system are great and help explain the significant increase in concentration that has occurred in the U.S. economy.

Antitrust cases present opportunities for experts, typically economists, to express opinions on both the liability and the damages sides of the case.2 An antitrust case is typically a larger project than a commercial damages case even though both involve commercial damages. While economists are the most common type of expert working on antitrust cases, there are also opportunities for accountants to work on certain aspects of the analysis.

Antitrust Laws

The main antitrust laws are:

- Sherman Antitrust Act

- Clayton Act

- Federal Trade Commission Act

- Celler‐Kefauver Act

- Hart‐Scott‐Rodino Act

Of these, the Sherman Act is the most important.

Sherman Act

The Sherman Act is the cornerstone of U.S. antitrust laws. Signed in 1890 by President Benjamin Harrison, it was named after Senator John Sherman. The law was part of an effort to control the anticompetitive activities of large trusts that started to exercise growing influence over corporate America. The trusts were often under the control of major banks, such as Morgan Bank. These trusts gained voting power over large amounts of equities of various companies and then used the voting rights associated with these shares to merge and combine various companies. The goal of these transactions was to try to create larger and more economically viable entities.

It is ironic that just after the passage of the country’s first major piece of antitrust legislation, the first merger wave took place.3 Between 1898 and 1904, a major wave of mergers and acquisitions occurred. This wave featured many horizontal combinations that resulted in markedly increased concentration in many industries. There are several reasons why the Sherman Act did little to influence the large number of horizontal combinations. Among them was the difficulty that the enforcers at the Justice Department had in interpreting a law that they wrongly believed was so broad that it could be applied to any commercial transaction. That, combined with the limited resources of the department, led them to put the Sherman Act to little use during the merger wave.

The two main sections of the Sherman Act are described in Table 11.1.

Given the uncertainty on the part of the courts and the Justice Department about how the Sherman Act should be used to foster competition, legislators passed two other laws in 1914 to facilitate antitrust enforcement. These were the Clayton Act and the Federal Trade Commission Act.

Clayton Act, 1914

There are four main components of the Clayton Act; they are described in Table 11.2 along with the section of the act to which they apply.

Federal Trade Commission Act

In 1914, the Federal Trade Commission Act was passed at the same time as the Clayton Act. Among its purposes was to establish an agency charged with the enforcement of anticompetitive practices and mergers. In 1938, the law was expanded to also focus on false or deceptive advertising. The commission was given investigative powers and the ability to hold hearings and issue cease‐and‐desist orders.

TABLE 11.1 Main Sections of the Sherman Act

| Section 1 | Outlaws all contracts and combinations that restrain trade. |

| Section 2 | Makes the process of monopolization and attempts to monopolize illegal. It does not necessarily make monopolies illegal but makes actions a person or firm might take to monopolize a market illegal. |

TABLE 11.2 Selected Sections of the Clayton Act

| Section 2 | Prevents price discrimination except that which can be justified by costs economies. This was further clarified and enhanced by the Robinson‐Patman Act of 1936. |

| Section 3 | Makes illegal tying contracts (which tie the purchase of one product to the purchase of another) and exclusive dealing (which results in the impairment of competition). |

| Section 7 | In its original wording, made illegal the purchase of stock of competing corporations that results in reduced competition. Amended under the Celler‐Kefauver Act of 1950, which closed the asset loophole and made the law apply to both stock and asset acquisitions. The Celler‐Kefauver Act also made vertical and conglomerate mergers and acquisitions illegal if they have an adverse effect on competition. |

| Section 8 | Makes illegal interlocking directorates of competing corporations. |

Celler‐Kefauver Act

The Celler Kefauver Act, passed in 1950, strengthened the Clayton Act while also amending the Sherman Act. It has been referred to by some as the anti‐merger act. It closed the asset loophole in the Clayton Act that had allowed asset acquisitions that were anticompetitive. The Celler Kafeuver Act also gave the government the ability to halt vertical and conglomerate acquisitions that it believed were anticompetitive. The passage of this law set the stage for some of the intense antitrust enforcement that took place in the 1950s and 1960s.

Hart‐Scott‐Rodino Improvements Enforcement Act of 1976

The Hart‐Scott‐Rodino Act was designed to prevent the completion of mergers and acquisitions, which regulatory authorities might find objectionable. Under Hart‐Scott‐Rodino, a merger or acquisition cannot be completed until either the Justice Department or the Federal Trade Commission gives its approval. This approval process requires that the merging firms submit a 16‐page form that includes various business data broken down by Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) codes. The Justice Department and the Federal Trade Commission decide between themselves which has jurisdiction.

Following the submission of the required forms, the regulatory authorities respond within certain stipulated time periods (which vary depending on whether the deal is a cash or securities offer). The authorities can extend the response period to an additional number of days; this is usually a sign that they have problems with the deal. Given the more relaxed pattern of antitrust enforcement in recent years, merging companies have been asking for an early termination of the Hart‐Scott‐Rodino waiting periods based upon a lack of antitrust concerns.4

Antitrust Enforcement

Antitrust enforcement is the joint responsibility of both the Justice Department and the Federal Trade Commission. When the Justice Department wants to take action, it can bring a civil suit in federal court. Among the tools at its disposal are injunctions, which it can wield to halt the objectionable activities. It can also pursue criminal proceedings against the targeted individuals or companies.

The Federal Trade Commission, however, can take action that is brought to an administrative law judge whose decision is then reviewed by the Federal Trade Commissioners. The Federal Trade Commission may get a cease‐and‐desist order to halt the illegal activities.

In addition to antitrust actions being pursued by the Justice Department and the Federal Trade Commission, individuals also have the right to file suits alleging antitrust violation. If successful, such suits can result in an award of treble damages.

Basic Concepts Underlying Antitrust Enforcement

Antitrust law is designed to prevent private sector companies from engaging in conduct that reduces economic welfare. Companies may increase their market power through legitimate means such as through fair competition. However, when market power is increased though noncompetitive means, then it may draw the attention of antitrust regulators. However, market power that is achieved through legitimate competition is normally thought of as not being an antitrust violation. We say normally in recent years some tech companies have achieved very dominant positions in the marketplace and this has raised some concerns as to whether their mere size and power preempts future competition.

There are two major steps in the analysis of actions that may warrant the attention of antitrust regulators. The first is an examination of the conduct at issue to determine if it was anticompetitive. An example of such conduct could be price fixing. In fact, price fixing is considered per se illegal, which means the conduct is illegal and it is not necessary to determine if the conduct resulted in economic harm. Per se illegality is based upon the implicit assumption that a reduction in economic welfare will likely occur while it is also likely that increased economic welfare will not occur.

There are several main means that have often been used to achieve enhanced market power. One is through mergers and acquisitions. Through such deals a company may possibly achieve a market share that allows it to dominate rivals and hurt consumers. Another means could be when competitors collude with each other in a manner that reduces economic welfare. Still another is through exclusionary conduct, which, for example, may possibly push rivals out of the market or weaken them so that they are not able to compete effectively.

The second step in the process involves an analysis of the impact on economic welfare. Regulators must prove not only anticompetitive conduct but also why that conduct adversely affected the level of competition in the market. As the U.S. Supreme Court noted in Brunswick v. Pueblo, antitrust laws are designed to protect the level of competition, not specific competitors.5 There are several reasons why this is important for antitrust regulators to keep in mind. Effective regulation can be a time‐consuming and costly process and many apparent violations may not be worth pursuing. However, the whole issue of not protecting competitors from large, winner‐take‐all, firms is being reevaluated in light of the great consolidation that has occurred in many US industries.

Economics of Monopoly

Antitrust laws are based on the principle that there are certain benefits of competition that are reduced when markets are monopolized. From a legal perspective, the basic element of a monopolization claim are “(1) the possession of monopoly power in the relevant market and (2) the willful acquisition or maintenance of that power as distinguished from growth or development as a consequence of a superior product, business acumen, or historic accident.”6 A claim of attempted monopolization requires the plaintiff to prove a “dangerous probability” of achieving monopoly power.7

In order to understand why the law seeks to promote competition and avoid monopolies, it is necessary to understand the benefits of market competition. In order to understand these benefits, it is necessary to explore the microeconomics of market structures. In microeconomics, there are several different broad forms of market structure. At one extreme is pure competition, which is a market structure characterized by many independent sellers each selling a small fraction of total market output. Being so small, their impact on the market is insignificant, and they cannot do anything to influence market price. That is, the market price does not change when they vary their output. In addition, pure competition assumes that the products produced in the competitive market are homogeneous and undifferentiated. Based on these assumptions, the firms in the industry are price takers; they cannot do anything to influence market price. The assumption of being a price taker means that the demand curve is a flat, horizontal line. This line also becomes the firm’s marginal revenues curve. The marginal revenue function is the function that shows how much additional revenue a firm receives when it sells another unit of output.

The profit‐maximizing output of the competitive firm is shown in Exhibit 11.2 as qc. As with all types of firms, the profit‐maximizing output is selected as the point where marginal revenue equals marginal costs. The difference in the case of pure competition is that the marginal revenue curve is flat and is the same as the demand curve. In a monopoly, the only seller in the market is the monopolist. Therefore, the demand curve that the monopolist faces is the demand curve for the product itself.

Like all firms, even purely competitive ones, the monopolist selects its profit‐maximizing output by where marginal revenue and marginal costs are equal. The difference between this market structure and pure competition is that with the demand curve having the usual downward‐sloping structure given by the inverse relationship between quantity demanded and price, the marginal revenue is also downward‐sloping and below the demand curve. The intersection of the upward sloping marginal cost curve with the downward‐sloping marginal revenue function gives us the profit‐maximizing output Qm shown in Exhibit 11.2.

EXHIBIT 11.2 Perfectly competitive industry and firm.

It is possible for us to compare this monopolistic output with that of pure competition by trying to hypothesize what output this monopolist would produce if it acted as if it were operating under pure competition. Exhibit 11.2 shows that the purely competitive industry structure results in a larger market output, which, in turn, causes market price to decline. These fewer units traded in monopoly result in a welfare loss – this is the loss of consumer and producer surplus. This is shown in the shaded region in Exhibit 11.2.

Use of Standard Economic Models

Standard economic models of market structure, such as the model of a purely competitive market compared to a monopolistic market structure, are based upon certain simplifying assumptions that may not compare well to specific firms and industries that may be involved in antitrust litigation. While these models may yield strong and convenient conclusions, they cannot be blindly applied if they do not fit the facts. This was the case in Concord Boat Corp. v. Brunswick Corp., where the court excluded an economist’s testimony who opined that in a two‐firm market, the assumptions of equal market shares drawn from a standard Cournot duopoly model should apply and that one company had a share greater than 50%; this had to be attributable to wrongful conduct. In this case the court concluded that the assumptions from the standard Cournot model – that the products and their costs be identical – would normally not be the case in a typical industry. Here the expert failed to adapt the model to fit the real‐world differences between the two producers and too blindly applied the simple textbook microeconomics.

Antitrust Injuries

For a plaintiff in an antitrust case to collect damages, the harm must be caused by an antitrust injury. An antitrust injury is one that is caused by anticompetitive behavior that is proscribed by the relevant antitrust laws. The focus of the enforcement of antitrust laws is on the consumer and opposed to protecting competitors. Anticompetitive behavior that has adverse effects on consumers will draw the attention of enforcement authorities more than competitors who may have been harmed by the anticompetitive behavior. This is due to the fact that enforcement authorities consider their role to be one of protecting consumers as opposed to protecting competitors from each other. This is not a new concept. In fact, in Brown Shoe v. United States, the first case in which the Supreme Court interpreted the Celler‐Kefauver Act, the court made this point clear when it said, “It is competition not competitors which the Act protects.”8 This has been the position of the courts in the United States and also is how competition policy is enforced in the European Union.

In trying to establish damages, it is not enough for the plaintiff to show it has incurred damages. It must show that it has incurred antitrust damages. In Brunswick Corp. v. Pueblo Bowl‐O‐Mat, the Supreme Court unanimously found that the plaintiff did not incur an antitrust injury. In its opinion, the Court stated, “For plaintiffs in an antitrust action to recover treble damages on account of § 7 [Clayton Act] violations, they must prove more than that they suffered injury which was causally linked to an illegal presence in the market; they must prove injury of the type that the antitrust laws were intended to prevent and that flows from that which makes the defendants’ acts unlawful. The injury must reflect the anticompetitive effect of either the violation or of anticompetitive acts made possible by the violation.”9

Fact Versus the Amount of Damages in Antitrust Cases

Economic analysis in antitrust cases can be divided into two parts: establishing the fact that damages occurred and actually measuring the damages. The analysis of antitrust cases is similar to the analysis of other types of cases, such as employment and personal injury analysis. First, it must be established that the plaintiff incurred measurable damages that were caused by the actions of the defendant. Some courts have referred to this process as establishing the fact and the amount of damages. The fact of damages itself has two parts: proving that the plaintiff was damaged and that these damages were caused by the defendant.10 Establishing the fact of the damages is the key first hurdle that an antitrust plaintiff must traverse. Courts have used phrases such as reasonable probability11 and reasonable certainty12 when describing the standard to be used in establishing the fact of damages and the causal relationship between the defendant’s actions and the damages incurred by the plaintiff.

The strict requirements in establishing the fact of the damages present many opportunities for defendants to find other factors that could have caused the plaintiff’s damages. These factors will vary from case to case, but often they may be found in the economic and industry analysis that was covered in Chapters 3 and 4. The defendant may accomplish its goals even if it cannot conclusively prove that such other factors caused the plaintiff’s damages. The defendant may be able to accomplish its goal by raising doubts about the causal link put forward by the plaintiff. For example, in the United States Football League v. National Football League, the defendant was able to establish that factors such as mismanagement were important explanatory variables.13

A good example of a defendant finding relevant factors other than the anticompetitive conduct is the Brunswick Boat Motor case.14 In this case, the plaintiff’s expert assumed that in a world without the anticompetitive behavior of the defendant, the plaintiff’s product and the defendant would have equal market shares. In the actual world, the defendant had a 70% market share, and the plaintiff’s expert assumed that the difference in market shares was the result of the alleged behavior. However, the defendant was able to show that the plaintiff’s expert ignored some very important other factors, such as the fact that the plaintiff’s product had major product defects, which led to a large‐scale product recall, which, in turn, caused buyers to switch to the defendant. This underscores the fact that each expert has to be knowledgeable about the conditions and major events occurring in the industry. Often an industry expert, and a candid client, can be quite helpful to the damages expert in this regard.

Once the fact of the damages has been established, courts tend to apply a more relaxed standard to measuring the amount of the plaintiff’s damages.15 This is partially due to the fact that once the world has been changed by the defendant’s conduct, it is difficult to reconstruct the position of the plaintiff. While the burden of proof may be less for measuring damages, the analysis still must be nonspeculative. If the defendant can show that the plaintiff’s damages analysis is speculative, then such damages may not be recoverable.

Interpretation of Antitrust Violations: Structure Versus Conduct

There are two opposing schools of thought in antitrust enforcement. The structure school of antitrust sees that the mere possession of monopoly power is by itself an antitrust violation. Under this view, a firm is guilty of an antitrust violation even if it did not engage in conduct that would otherwise be considered a violation of antitrust laws. Mere size alone would be enough to be found guilty of antitrust violations. This would be the case even if the firm did not do anything to limit the ability of other firms to enter the market and to limit the ability of the other companies in the industry to compete.

Under the conduct view, the mere possession of monopoly power is not a per se violation. The firm would have to engage in other unacceptable conduct in order for it to be guilty of antitrust violations. It is even possible that one firm that had a large market share but did not engage in any anticompetitive behavior could be innocent of antitrust violations. At the same time, a firm that had a smaller market share but took actions to try to limit competition could be found guilty.

Changing Pattern of Antitrust Enforcement

Initial Comments

In this section of this chapter we devote space to reviewing the cases that underlie the development of antitrust law. At first this may not seem very useful in light of the fact that the U.S. economy has changed so much over the past century that one might question the relevance of laws designed to regulate old economy companies in the age of new economy companies, such as Facebook, Google, and Amazon. However, that difference is the point of this review. The current U.S. antitrust laws are old laws that have been changed little and are not well equipped to deal with the nuances of modern companies. The application of the “old laws” has, unfortunately, evolved in a limited way, through various legal decisions that have tried to apply them to new companies and their modern technologies. The problem is lawmakers have been more focused on political fights than on the job that they were actually hired for: passing laws that are relevant and facilitate economic growth and the welfare of the people who elected them.

Evolution of the Application of Antitrust Laws

In the early part of the twentieth century, the courts focused on a combination of structure and conduct. They sought companies that clearly had very large market shares, but they also considered their anticompetitive conduct. These decisions quickly evolved into the rule of reason, in which behavior became the main focus of the court.

Early Cases

In 1911, two major antitrust cases were brought against two companies that held dominant positions that they achieved through the use of various forms of anticompetitive behavior. The first of these is the Standard Oil case. The Court focused on the many anticompetitive acts in which the company engaged to garner a 90% market share of the petroleum industry.16 The large market share raised the Court’s suspicions. It was even more concerned, though, with the variety of anticompetitive behaviors that the company engaged in to drive out competitors in order to achieve this market share. Such behavior included industrial espionage and local price wars. The court’s solution was to require dissolution of the company; it was disassembled into 34 separate companies.17

In the same year, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against American Tobacco for similar reasons.18

Rule of Reason and the U.S. Steel Case

The evolution of the rule of reason took a major step with the U.S. Steel case.19 Here U.S. Steel was shown to have a dominant position as evidenced by its market share – which was far larger than that of any of its competitors. The firm was formed through a consolidation of many different plants and competitors, leaving it with the majority of the market’s production. This process was part of an overall consolidation that was occurring throughout the U.S. economy and constituted the first merger wave in American economic history. However, the court concluded that even though U.S. Steel did possess market power, it did not engage in any offensive conduct. The court found that even though the company accounted for approximately one‐half of the market, its market share had actually fallen from as high as 66%.

In the U.S. Steel case, the court focused on the fact that the company did not make any attempt to price its products in a manner that would drive out competitors. In its decision, the court stated that size alone was not anticompetitive, and U.S. Steel did not use its dominant position to limit competition.

Structure and the Alcoa Case

The position of the court shifted in 1945 when it moved away from the rule of reason and began to consider size by itself to be objectionable. In his decision, Judge Learned Hand found that Alcoa had built up its bauxite reserves with the intention to monopolize the aluminum industry.20 He was particularly impressed by the dominant position of Alcoa. Hand was concerned that even if the company had not used its market power to engage in anticompetitive conduct, the mere possession of such power, and the clear ability of a firm to dominate markets, was sufficient to constitute an antitrust violation. Judge Hand’s solution was to force Alcoa to sell off parts of the company to competitors Reynolds Metals and Kaiser Aluminum and not to build any more plants for a period of time.

It is noteworthy to mention that the Alcoa decision was followed by another major antitrust decision in the following year. In 1946, the court continued a pattern of more intensive antitrust enforcement when it found the management of A&P guilty of anticompetitive behavior.21 In the same year, the big three tobacco companies, American Tobacco, Liggett and Myers, and R.J. Reynolds, which controlled 75% of the market, were found guilty of monopolization.22 In later years, however, the “Alcoa doctrine” was discredited, and the mere possession of a monopoly position was not construed to be a violation of antitrust laws.

1950s–1960s

Following the Alcoa and the A&P decisions, antitrust enforcement grew intense. Antitrust laws were buttressed by the passage of the Celler‐Kefauver Act in 1950, which strengthened the Clayton Act. It bolstered the decisions of the 1940s to create an environment in which the Justice Department and the Federal Trade Commission wielded considerable power. The fact that there were not as many landmark decisions in this period is not indicative of the intensity of antitrust enforcement. Companies were often reluctant to pursue a case through trial and ended up settling by entering into agreements with the Justice Department.

When companies wanted to expand in the 1960s, they ran into extremely stringent antitrust enforcement. It limited their ability to expand within their own markets or even outside their usual industries. The intense antitrust enforcement of this period combined with the desire of companies to expand following the longest recovery in modern U.S. economic history caused the third merger wave. This wave, which took place in the late 1960s, featured conglomerate mergers – mergers outside of the company’s industry.23 Companies were reluctant to expand within their own industries because they knew that such moves were often challenged. The antitrust enforcement became so intense that even conglomerate mergers were questioned.

On January 17, 1969, the last day of the Johnson administration, the government began its famous lawsuit against IBM.24 The case dragged on for years but finally went to trial in 1975. The government alleged that IBM, which commanded approximately three‐quarters of the mainframe computer market, engaged in various anticompetitive actions (such as predatory pricing), tying of various computer products (such as hardware and software), and other acts. The case was very costly and very time consuming; in the end, the case was dismissed. Some have termed this case the Justice Department’s Vietnam.

1970s–1980s

The 1970s and 1980s were periods of more relaxed antitrust enforcement. More pro‐business administrations in Washington, DC, came to power and placed similarly minded individuals in positions of power at the Justice Department. These individuals held the belief that even in oligopolistic market structures, there can be significant competition among the participants of the industry. Broader definitions of markets were applied, and consideration was given to factors such as global competitiveness.

One landmark antitrust development that took place in the 1980s was the dismantling of the Bell System. This event can be traced to a 1974 Department of Justice lawsuit that contended that AT&T was hindering competition of fledgling rivals such as MCI and that AT&T obstructed telecommunications equipment companies from selling to the components of the Bell System that it controlled. The suit contended that AT&T used its monopoly of the local telecommunications market to dominate the long‐distance and equipment markets. AT&T argued that its control of the Bell System had resulted in the finest telecommunications system in the world. It stated that their dominant market position was actually good for the market. However, fearful that the ultimate legal result might be adverse, AT&T agreed to a consent decree, which broke up the system. This breakup separated the operating systems from the long‐distance entity while also releasing the equipment component from the combined entity. The operating companies were grouped into seven large regional holding companies, which were consolidated in later years through mergers and acquisitions. It is ironic that in the 1990s and 2000s, these holding companies would compete with AT&T and one of them, SBC Corp., acquired AT&T in 2005 and assumed the AT&T name. SBC Corporation – which stands for Southwestern Bell Corporation, a former Baby Bell – had already acquired Pacific Telesis, another former Baby Bell spun off in the breakup of AT&T. Thus the acquisition of AT&T by SBC reconstituted much of the former AT&T without the vertical integration component of AT&T. Verizon, another former Baby Bell, is another part of the old AT&T and represents the merger of two other former Baby Bells, Nynex and Bell Atlantic.

The two‐decade period from 1970 to 1989 saw the rise of what is referred to as the Chicago School influence on industry organization and antitrust law. Relationships, such as vertical relationships, some of which had been viewed by courts as being anticompetitive, were seen to have some beneficial aspects that might even work to the benefit of consumers. The change in thinking brought about by Chicago School professors such as Richard Posner, Robert Bork, and Sam Peltzman is still quite influential in court decisions to this day.25

1990s

The 1990s marked a slight move away from the more relaxed posture of antitrust enforcement that was the norm during the 1980s. Mergers that may not have been questioned in the 1980s were given closer scrutiny by the Justice Department. Certain major firms that held dominant positions in markets, such as Microsoft, were watched carefully. They were challenged when they attempted acquisitions within their broadly defined industry category or when they tried to market products that could be construed as giving their products an unfair advantage over competitors. The Microsoft case was the highlight of the Justice Department’s increased aggressiveness in the enforcement of antitrust laws. The Justice Department’s suit alleged that Microsoft bundled its Web browser, Internet Explorer, with its dominant operating system in a manner that violated Section 1 of the Sherman Act.

The Justice Department argued that in doing so, Microsoft violated a 1994 order‐and‐consent decree when it bundled these products together in sales to original equipment manufacturers and consumers.26 The Justice Department experienced an initial victory that was greatly tempered by subsequent setbacks. In United States v. Microsoft Corp., the U.S. District Court found that Microsoft violated Sections 1 and 2 of the Sherman Act through what this court saw as Microsoft’s efforts to use its Windows operating system to hold down competition in related areas such as Web browsers. The court based its decision in part on the Jefferson Parish Hospital District No. 2 v. Hyde and Northern Pacific Railway Co. v. the United States decisions.27 However, the U.S. Appeals court for the D.C. Circuit affirmed the District Court’s decision on monopoly maintenance but reversed its decision on attempted monopolization and tying as well as the District Court’s suggested remedy.28 The Justice Department declined to pursue a breakup of Microsoft, and in November 2001, the parties entered into a settlement agreement that placed restrictions on Microsoft’s behavior.

Antitrust and the New Economy

The Justice Department’s pursuit of Microsoft drew attention to the application of traditional antitrust laws to “new economy companies.” Richard Posner defines new economy companies as firms operating in one of three areas:

- Computer software manufacturers

- Internet‐based companies (such as AOL)

- Communication services and equipment manufacturers designed to support the above two categories29

Posner pointed out that the economics of these industries differs markedly from the traditional capital‐intensive industries that antitrust laws were designed to regulate. These traditional firms are so embedded in economics that they are used as the model for presentations on the determination of optimal output and price in many microeconomics textbooks. While such firms experience economies of scale in production, these scale economies are bounded by the limitations of the plant or plants they operate. This is not the case with many of the new economy businesses. They have falling average costs over large output ranges, and, unlike their old economy predecessors, their businesses are not capital‐intensive. The other obvious difference between these two types of industries is that the main output of the new economy companies is intellectual property. Such “goods” are characterized by very significant fixed, up‐front costs but comparatively low marginal costs. The “production” component of these costs may be close to zero; however, there may be other nonzero marginal costs, such as selling costs.

The growth of some of the major tech giants such as Amazon, Apple/Alphabet, Facebook, and Google has drawn new attention to the potential need for reenergized antitrust enforcement in the U.S. Indeed, this has now become an issue that is widely discussed in the antitrust law literature even if regulators seem deaf to this growing challenge.(*) Part of the reason for that is there are concerns that the sheer size of some of these companies has given them monopsonist power to control wages of workers and that this has increased inequality as shareholders and upper managers of these companies have enjoyed huge increases in wealth while so many workers are falling further and further behind.30 The issue is complex and beyond the bounds of this book.31 However, it is relevant because some political factions have seized upon this issue and this may give rise to greater antitrust enforcement. This was underscored in 2019 when the Justice Department announced that it was doing a sweeping review of how online platforms may have achieved market power and whether this has adversely affected smaller competitors and consumers.32 In 2020 the Justice Department announced that it was also doing a review of prior acquisitions by the tech giants.

Monopolization and Attempts at Monopolization

As noted earlier, Section 2 of the Sherman Act prohibits a company from monopolizing an industry or taking actions that are designed to achieve this goal. It is important to note, however, that it is not a violation of antitrust laws to develop a monopoly position by lawful methods. Monopolists can choose to compete as aggressively as competitive firms to achieve optimal profits.

The situation is different when the monopoly position is attained or maintained by unlawful means. In this case, whether the firm truly has a monopoly position becomes more important. As part of the process of making a judgment on whether a firm has a monopoly position, various quantitative microeconomic measures can be employed. One of the first steps in this process is to define the relevant market.

Market Definition

For a plaintiff to prove a monopolization claim, it needs to define the relevant geographic and product market.33 The definition of a market determines the products and services that are competing with the product in question as well as the geographical area within which such competition occurs. Therefore, a market can be defined in two broad ways – geographic markets and product markets. Each way has its own quantitative measures that are employed.

Geographic Market Definitions

Geographic definitions of markets have varied considerably over time as the intensity of antitrust enforcement has varied. As markets have become broader and more internationalized, the definition of the relevant markets in some instances has widened. The degree to which increased internationalization is relevant to a case depends on the industry and the facts of the case.

Economists usually define the geographic boundaries of a market by judging whether an increase in the price in one market affects the price in another market.34 Other factors related to this market’s definition are variables such as transportation costs that are incurred to move products from one market to the other. The more significant the transportation costs in the total costs of the product, the more likely that such costs might serve to segregate the market into separate markets. However, the expert needs to consider factors that could offset these costs, such as the existence of storage or distribution facilities.

Regulatory factors may play a role in the definition of a geographic market. For example, governmental regulations that prohibit selling the product or service outside certain boundaries may help define the geographical boundaries. Such factors have played an important role in the banking industry, although their importance has declined significantly as the industry has undergone deregulation.

If marketing and advertising play a major role in generating demand for the product or service, then the geographic limitations of the often‐used advertising media may help define the geographic market. However, as the marketing and advertising industry have themselves undergone major changes, the role of this factor may vary considerably.

In some cases, such as those involving hospital mergers, economists have tried to employ certain tests to understand the market. The Elzinga‐Hogarty test was introduced in the 1970s as an attempt to understand the movements of commodities.35 An Elzinga‐Hogarty analysis examines the movements of products or services into and out of a possible geographic market area to draw conclusions regarding the relevant geographic market boundary. It has been used extensively in hospital‐related cases, although many criticize its use as the sole tool to determine geographic markets. Even though it has been used in antitrust cases involving hospitals, a debate exists as to how useful an Elzinga‐Hogarty analysis really is in an antitrust case. One drawback is that it examines historical flows and may not be as useful in determining future market activity.36 Some also believe that it fails to define the market for antitrust purposes.37 Another tool that is sometimes employed is critical loss analysis, which considers how much of a price increase a prospective monopolist could withstand before its profits would start to decline.

Product Market Definitions

The broader the market, the less likely it is that a given firm is found to have monopolized it. Competitive products are those that are substitutes for one another. Products X and Y are demand substitutes for each other if an increase in product X causes an increase in the quantity demanded of product Y. Products A and B are supply substitutes if an increase in the price of product A causes companies that are producing B to alter their production mix and increase their production of A.

Price and Substitutability

The degree of substitutability between two products is not constant; it varies as the price changes. At a low price, two products (X and Y) may not be substitutable, but at higher prices, they may become substitutes. There tends to be a price at which consumers look for substitutes. The fact that at a higher price of good X its seller faces competition from substitutes does not mean that the company selling X lacks market power. Its market power may lie in the fact that it has the ability to sell the products at as high a price as possible before it faces significant competition.

One classic example of the varying degree of substitutability as a function of price is the Cellophane case.38 In this case the court concluded that DuPont did not have market power because at the prices that cellophane was selling for, there were a number of other substitutes, such as paper bags. The decision drew attention because it was clear that price exceeded marginal cost.

Determining the Existence of Substitutes

A simple method of determining the degree to which products are considered substitutes is to survey the marketing and sales professionals in the industry. Salespeople without any knowledge of economics may know very well who their competition is as they try to sell their products. Marketing professionals who develop marketing campaigns usually also have intimate knowledge of who their major competitors are.

USING CORRELATION ANALYSIS

If two products are substitutes, then presumably their prices move together as they engage in price competition. The degree to which these prices move together may be measured using correlation analysis. Correlation analysis is discussed in Chapter 2 in the context of causality in commercial litigation. If the correlation coefficients are high, this usually indicates that the products are substitutes. Low correlations do not support the assertion that products are substitutes. However, this is not to imply that correlation analysis alone is conclusive.

Another method of determining whether a particular product, Y, may be a substitute for another one, X, is to find yet another product, Z, that is accepted as a substitute for X. Correlations of the movements in the prices of X and Z can be computed to measure their degree of association. This value is then used as a benchmark.39 This correlation is then compared to the correlation between the prices of X and Y. Very different correlation coefficients fail to support the assertion that X and Y are in the same market. However, this is a general statement, and each case has other factors that may offset this difference in the correlation coefficients.

CROSS‐PRICE ELASTICITY OF DEMAND

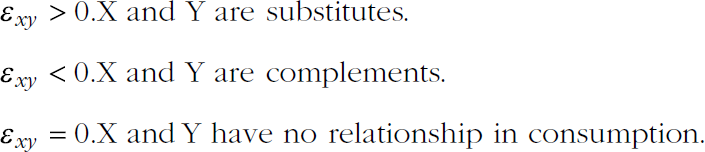

A quantitative measure that may be useful in assessing the extent to which two products are substitutes is the cross‐price elasticity of demand. It measures the percentage change in the quantity demanded of good X in response to a given percentage change in the price of good Y. This measure is expressed as shown in Equation 11.1.

Two goods can have three different values for the cross‐price elasticity of demand: positive, negative, or zero. Such values reflect the extent to which they are substitutes, complements, or have no interrelation in consumption. Substitutes are goods that can be used in place of the good in question because they have some similar characteristics in the eyes of consumers. Complements are goods that must be used together. Many consider tea and lemon complements; Coca‐Cola and Pepsi Cola are considered substitutes.

When the price of good Y increases and the quantity demanded of X increases, X and Y are said to be substitutes in consumption. When the price of Y rises and the quantity demanded of X decreases, the two goods are said to be complements. If there is no change in the quantity demanded of X when the price of Y changes, the consumption of the two goods may not be interrelated. This relationship is summarized as:

OWN‐PRICE ELASTICITY OF DEMAND VERSUS CROSS‐PRICE ELASTICITY OF DEMAND

The own‐price elasticity of demand is the percentage change in the quantity of X that occurs as a result of the percentage change in the price of X. This is different from the cross‐price elasticity of demand, which is the percentage change in the quantity of X in response to a percentage change in the price of Y. Both elasticity measures are relevant to antitrust analysis and a firm’s market power. The own‐price elasticity of demand is relevant to understanding the ability of the firm to raise price above marginal costs and enjoy above‐normal profits; the cross‐price elasticity of demand is also relevant in assessing competitive effects.

Market Definition and Microeconomic Analysis

Each case is different and each presents its own data limitations which may limit the type of analysis an economist may conduct. However, the expert will likely be questioned about the analysis that was done and about what could have been done but was not. This was an issue in Lantec, Inc. v. Novel, Inc., where the Court of Appeals was troubled about the analysis of the plaintiff’s expert, John Beyer of Nathan Associates. The Court of Appeals agreed with the district court when it found that “Dr. Beyer used (a) unreliable data; (b) did not understand computers or the computer market; (3) testified that the relevant market was defined by consumer purchasing patterns but did not conduct or cite surveys of consumer preferences; (4) did not calculate the cross‐price elasticity of demand to determine which products were substitutes; (5) changed his opinion from the opinion he gave in an earlier expert report; and (6) did not address changes in the computer market.”40

Market Power

In microeconomics, market power is measured by the ability of the seller to charge a price above marginal costs. Marginal costs are taken to be the price that would prevail in a purely competitive market when sellers set price equal to marginal cost. However, few industries correspond to the exact characteristics of a purely competitive market. These characteristics are:

- Many independent sellers

- Perfect information

- Homogeneous, undifferentiated products

- No barriers to entry

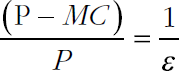

Most firms have some element of market power, whereas others possess significant market power. To the extent that a given firm has some market power, its price exceeds marginal costs. One of the problems of applying a concept such as marginal cost is that it is difficult to measure. If, however, a reasonable approximation can be made, then market power is measured using the Lerner Index (LI). This index, named after the economist Abba Lerner, may be expressed as shown in Equation 11.2.

The left‐hand side of this equation is called the price‐cost margin. This margin is a function of the price elasticity of demand – ε. Specifically, the magnitude of the margin is inversely related to the price elasticity of demand. That is, when the price elasticity of demand is low, price is significantly greater than marginal costs. However, when the price elasticity of demand is high, marginal costs are very close to price.

The Lerner Index is useful in that it shows how a monopolist’s market power is related to its ability to set price above marginal costs. The more inelastic demand is, the greater the monopolist’s ability to widen the gap between price and marginal costs.

It is important to note, however, that merely having monopoly power, as measured by the ability to set price above marginal costs, does not mean that a firm makes a profit. It could be that the firm has fixed costs that make a positive profit at its optimal output – the output where marginal revenue equals marginal costs – impossible. This is shown in Exhibit 11.3. In this example, average costs (AC) are always above the demand curve, which means that price (P) is always less than average costs even at the optimal output qm.

A Lerner Index can be computed for an entire industry as opposed to just one company. The industry version of this index can be expressed as shown in Equation 11.3:

where:

- LII = the LI for the industry

- Si = the market share of the ith firm

- N = total number of firms

EXHIBIT 11.3 Average costs exceed price.

The interpretation of the industry LI is similar to the firm version. The higher the value, the further we are from competitive conditions. While the industry index makes theoretical sense, it is difficult to apply to actual cases. It is easy to count the number of companies in the industry (N), but it is more complicated to try to reliably measure marginal costs or elasticities. Some academic studies have attempted to do this for various industries.41

Obviously, the mere possession of market power does not prove that anticompetitive behavior will take place. Some have argued that the relationship between market power and anticompetitive behavior is more complex and varies as a function of many factors such as market conditions and the price elasticity of demand.42

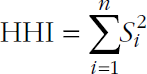

Measures of Market Concentration

In economics, there are two opposite types of market structure – pure competition and monopoly (see Exhibit 11.4). In pure competition, the firms lack market power; in a monopoly, however, the monopolist has some degree of market power. In reality, most industries are neither monopolists nor purely competitive. However, depending on how close they are to either end of the industry spectrum, some of the characteristics of either form of industry structure may apply. Toward this end, it is useful to measure the degree of concentration in an industry. This can be done in different ways, the most basic of which is to use concentration ratios.

EXHIBIT 11.4 Monopoly versus pure competition.

Concentration Ratios

Concentration ratios measure the amount of total market output that is accounted for by the top 4, top 8, or even top 12 companies in the industry. The greater the market share accounted for by a smaller grouping of firms, the closer an industry is to monopoly. Industries where the top 4 or 8 companies account for most of the industry output usually are considered oligopolies. An example of the wide range of concentration ratios in different industries can be found in the Census Bureau’s reports.43 It is important to keep in mind that one cannot judge the degree of competition in an industry by looking at concentration ratios alone. An industry can have a significant degree of competition even when there are relatively few competitors. There is some support, however, for what is known as the differential efficiency hypothesis, which is the view that firms with high market shares will tend to have high price‐cost margins and profits. There is support in the empirical research literature for the differential efficiency hypothesis.

Increased Concentration and Its Effects

It is clear that regulatory authorities have allowed certain industries to become much more concentrated through mergers and acquisitions. One such industry is the airline industry.44 Here mergers of large carriers have limited competition in certain markets and have even discontinued certain routes.

Grullon et al. have shown that over the last two decades, three‐quarters of U.S. industries experienced increased concentration.45 They showed that this increased concentration was associated with higher profit margins and positive abnormal stock returns. They also were able to relate these changes to “lax enforcement of antitrust regulations,” especially as it relates to mergers and acquisitions.

Azar et al. have shown that the adverse effects of increased concentration may be more pernicious than what simple concentration ratios and HHI measures show.46 This is due to the potential impact of common share ownership of competitors. In equity markets institutional investors, such as mutual funds, often hold large stock positions in companies that are competitors. Azar et al. have shown that this common ownership provides incentives for reduced competition. They traced these incentives to higher product prices.

Major concerns for the U.S. economy are that workers are not realizing significant real wage growth and there is a reason to believe that income inequality is rising. For example, David Autor et al. have shown that labor’s share of profits has declined.47 These troubling trends arise at a time when concentration in many industries has risen significantly. Covarrubias, Gutierrez, and Philippon analyzed the trends in corporate profits, investment, and market shares over the past 30 years.48 They found that in the 1990s, industry concentration was not as high, although increasing, yet price competition was greater and so was investment and productivity. However, they showed that after 2000, rising concentration and rising barriers to entry were associated with lower investment, higher prices, and reduced productivity. Indeed, Professor Philippon has opined that as the U.S. economy has gotten more concentrated and market power in certain industries has risen, partly due to the power of corporate lobbyists and how they influence U.S. politicians and their willingness to sell what little integrity they may have to the highest bidder, competition has declined, prices have risen above competitive levels, and productivity has declined. 49

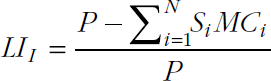

Herfindahl‐Hirshman Index

Concentration ratios are not very sensitive to changes in industry concentration caused by mergers among firms in the same size category. For example, if the top firms constitute 98% of total industry output and there is a merger between the sixth‐ and seventh‐ranked companies in the industry, the top eight concentration ratios will shed little light on the competitive effects of this change in control. To remedy such problems, regulatory authorities rely on the Herfindahl‐Hirschman Index (HHI). The index was created by economists Orris Herfindahl and Albert Hirschman. It is expressed as shown in Equation 11.4.

where:

- Si = the market share of the ith firm

HHI can be expressed as decimals and thereby it can range between 0 and 1. However, more typically it is expressed as whole percentages, which means the values can vary between 0 to 10,000 (1002). A value of 10,000 means the industry is a monopoly.

Given that the market shares of the firms are squared, the index places disproportionately greater weight on larger firms. In the example, the merger between the sixth‐ and seventh‐largest firms has little impact on the top‐eight concentration ratio other than to promote the relatively small, previously ninth‐ranked firm to the number‐eight spot. However, the HHI may rise significantly when the sixth‐ and seventh‐ranked firms merge.

In an effort to prohibit types of mergers and acquisitions that are unacceptable, the Justice Department has created merger guidelines in terms of the Herfindahl‐Hirschman Index. A competitive market is one that has a score of 1,500 or lower. If the HHI value is between 1,500 and 2,500 the market is considered moderately concentrated. When the HHI value is above 2,500 the Justice Department considers the market highly concentrated and any merger that increases the HHI by 200 points could create antitrust concerns.

EXHIBIT 11.5 Herfindahl‐Hirschman Index.

Source: Gustavo Grullon, Yelena Larkin, and Roni Michaely, “Are U.S. Industries Becoming More Concentrated?,” Review of Finance, April 23, 2019.

Exhibit 11.5 shows how the Herfindahl‐Hirschman index has markedly risen since 1987. This trend has come at a time when antitrust enforcement has declined. The combination of these two trends has raised concerns.

Concentration, Structure, and the Efficiency Debate

From a policy perspective, the importance of industry concentration is an outgrowth of the structure versus behavior and market efficiency debate that has been quite active since the passage of antitrust laws starting in 1890. Structure is important not just in the case of an outright monopoly but also in an oligopolistic market. Research studies that were published over a half century ago initially lent support to the importance of market concentration. For example, Joseph Bain analyzed the profitability of 42 different industries and found a relationship between greater concentration and higher industry profitability.50 Bain’s study was followed by several other studies that, to different degrees, provided support for “structuralist” arguments. Policy makers then latched on to these findings and sought to take actions to “deconcentrate” industries.

The structuralist views were opposed by the Chicago School of efficiency theorists, who found the higher profitability of some more concentrated industries to be the product of the success of more efficient firms. These researchers contended that the higher market shares of some firms were the product of their success in being more efficient than their competitors.51 This debate on the importance and relevance of industry concentration continues today. In a litigation context, it is determined by the empirical findings specific to the industry in question.

Common Types of Antitrust Cases

With the dramatic increase in mergers and acquisitions that occurred in the 1980s and 1990s, lawsuits involving alleged increases in market power resulting from such transactions may require antitrust analysis. These cases draw on the type of analysis that was discussed earlier. However, in addition to allegations of basic monopolization of markets, certain other types of antitrust violations arise: predatory pricing and tying contracts. Predatory pricing is a violation of Section 2 of the Sherman Act; tying contracts violate Section 3 of the Clayton Act. There is an abundant literature on each of these types of violations that is well beyond the scope of this chapter. However, an introduction is provided to some of the issues and tools that may be employed in a litigation environment.

Mergers and Acquisitions Antitrust Analysis

The 1980s featured a dramatic increase in both the number and size of mergers and acquisitions (M&A). This period was the fourth merger wave that occurred in U.S. economic history. It ended in the late 1980s with the collapse of the junk bond market. This helped fuel the high number of hostile deals that occurred, as well as the overall slowdown in the economy. However, after a relatively short hiatus, the pace of mergers and acquisitions increased in 1993, and the resulting merger frenzy surpassed even the lofty levels reached in the 1980s. This period was the fifth merger wave.52 That wave ended with the recession of 2001. In the next few years, though M&A volume picked up again, this next merger period, the fifth wave, was partially driven by the rapidly growing demand from private equity funds. This continued until the latter part of 2007, when the subprime crisis began to unfold. By 2008, and the start of the Great Recession of 2008–09, M&A volume was way down as deal financing dried up. In fact, the cutoff in financing led to large‐scale deal cancellations. Once the economy began to recover and enter the longest expansion of post‐war U.S. economic history, high deal volume returned. This period also coincided with the tremendous growth of certain very large firms in the tech sector. Their growth and apparent dominance became a very controversial issue.

Regulatory Framework

Mergers and acquisitions are highly regulated. Purchases of stock beyond the 5% threshold require the filing of a Schedule 13D disclosure statement pursuant to the Williams Act or Section 13(d) of the Securities and Exchange Act; tender offers require the filing of a Schedule TO pursuant to Section 14(d) of the same law. However, in addition to these securities laws, a special disclosure‐related law exists for the antitrust ramifications of mergers and acquisitions. This law, the Hart‐Scott‐Rodino Improvements Act, requires the filing of a form that includes data on sales by SIC (or now NAICS) code for merger partners above a certain size. This form is filed with both the Justice Department and the Federal Trade Commission; they determine which has jurisdiction. If the transaction is objectionable, they may ask for more information (which is usually a sign of a potential problem), or they will indicate that they oppose the deal. The purpose of the law is to give merger partners an advance ruling. This prevents the government from having to file a lawsuit after the fact and having to try to disassemble the combined entities.

Horizontal Mergers and Acquisitions

Section 7 of the Clayton Act, which was amended in 1950 by the Celler‐Kefauver Act to include asset transactions, makes illegal those deals in “any area of commerce” or in “any section of the country” that lessen competition or tend to create a monopoly. The wording of these excerpts from the law is revealing. The term “any area of commerce” implies that the industry definition is flexible. In addition, regional concentration becomes an issue under the wording “any section of the country.” The phrase “tend to create a monopoly” makes the law applicable even if the deal did not result in a clear monopoly. Given its broad wording, this section of the Clayton Act and the Sherman Act are potent weapons in the hands of regulators who are predisposed to oppose such deals.

One of the most common antitrust complaints in mergers and acquisitions has to do with increases in market power caused by horizontal transactions, such as a merger between rivals. This claim was asserted more often in the mid‐1990s as the industry consolidations of the fifth merger wave started to have an effect on the degree of concentration in some industries. This led to the Justice Department playing a more active role in examining, not merely rubber‐stamping, the mergers that took place.

In an effort to establish standards that potential merger partners could look to try gauge the government’s position on the competitive effects of a given deal, the Justice Department, starting in 1968, began to issue merger guidelines. The original version of these guidelines consisted of concentration ratios for industry structures that the Justice Department would consider less concentrated versus those that it would consider highly concentrated. These early guidelines were somewhat simplistic and inflexible. They were changed in 1982 when the Justice Department put forward the use of the Herfindahl‐Hirschman Index as an alternative to simplistic concentration ratios. The department set forth particular values of the index that apply highly concentrated (greater than 1800) as opposed to less concentrated industries. The guidelines were updated in 1992 when the Justice Department allowed for the consideration of other economic factors, such as the price elasticity of demand and the effect that a given price increase, such as 5%, would have on quantity demanded by consumers. In 1997, there was still another iteration of the guidelines, which allowed for efficiency effects to be taken into account in mergers that might otherwise be considered anticompetitive.

Vertical Mergers

As we have noted, the Clayton Act also provides for challenges of vertical, and even conglomerate, mergers and acquisitions. Challenges to vertical mergers are much less common than challenges to horizontal deals. For example, over the period 2000–2017 the FTC pursued 22 challenges to vertical mergers – “about one per year.”53

Vertical deals are those in which the participants have a buyer‐seller relationship (even if they were not necessarily buying/selling from each other at the time but were buying/selling to others in the same overall industry). The U.S. Supreme Court has decided relatively few major cases involving vertical mergers under the Clayton Act. The first in which it applied the Clayton Act was the DuPont case, where the Court found that DuPont’s acquisition of 23% of the shares of General Motors foreclosed a market to other suppliers of paint and materials that DuPont suppled.54 This led the court to conclude that the deal was anticompetitive.

The DuPont decision was followed five years later by the Brown Shoe case.55 Here the Court concluded that the primary vice of a vertical merger was the foreclosure of a market to competitors. In reaching its decision the court said market share might not be the critical factor, as opposed to horizontal deals where it is of primary importance. In vertical mergers the Court noted that other factors, such as the real purpose and goal of the merger, can possibly have greater importance.

Ten years after Brown Shoe, the Court found that Ford Motor Company’s decision to buy a spark plug manufacturer, Autolite, was anticompetitive, The Court also rejected Ford’s weak argument that by being combined with Ford, Autolite would be a more credible competitor in the spark plug business.56

While the early cases in which the Supreme Court applied the Clayton Act projected a dim view of some vertical deals, some other lower federal court decisions, such as the Second Circuit decision in Fruehauf Corp. v. FTC, took a different view. In Fruehauf the court approved a merger that was opposed by the FTC. In its reasoning, the court pointed out that K‐H, a brake and wheel manufacturer, the target of the vertical acquisition by Fruehauf, the largest U.S. truck manufacturer, was too small to have any significant effect on its competitors.57

In later decisions by other circuits, those courts looked to the potential efficiency enhancing effects of vertical mergers. These decisions seem to rely on the possibility of efficiency enhancements and costs savings being passed on to consumers even though there was not necessarily a basis to know that at the time of the decisions.58

The positive view of vertical deals continued until the 2018 decision by the District Court for the District of Columbia in which the court ruled against the Justice Department.59 “AT&T, a content distributor, and Time Warner, a content creator, argued that a merger was necessary in order to remain competitive with already vertically integrated companies such as Netflix, Hulu, and Amazon.”60 In reaching its decision the district court did allow for the possibility that the combination could possibly reduce competition. However, the court also said the burden to prove that was the government’s and that it had failed to prove it sufficiently to stop the merger.

In recent years, concern about new large mega companies, ones that dominate industries, have brought a new focus on vertical deals. When a vertical target is acquired by a huge company with great cash resources, does the target thereby gain a large competitive advantage over rivals? If those rivals also vie for business with the huge buyer, do they lose their ability to compete?

It is ironic that the Justice Department has revised its merger guidelines several times since it issued its 1968 Merger Guidelines. In its 1982 revision it added the use of the Hirfindahl‐Hirschman measure. Its guidelines were later revised in 1992, 1997, and 2010. However, the guidelines that govern vertical mergers have been unchanged since 1982. As companies have grown and have used vertical mergers to facilitate that growth, calls for a new focus on vertical deals have increased.

Predatory Pricing

The term “predatory pricing” refers to the use of price competition to drive rivals out of business and to prevent competitors from entering into the firm’s market. Obviously, one of the key tasks in a predatory pricing analysis is to determine whether the price competition was the product of ordinary competitive actions or was part of a predatory process. This is one of the problems of predatory pricing economic analysis – distinguishing predatory pricing from ordinary competition.61 Courts have recognized that cutting prices is one of the main forms of competition.62 In order to determine this, one must compare price to some measure of the alleged predator’s costs. This usually involves showing that the predator incurred losses, usually short‐run losses, in order to generate long‐term gains.

Predation is more likely in markets where the predator has certain advantages over current or potential rivals. These advantages may come in the form of larger size or lower costs. Certain game theory issues arise when the competitors do not know the other firm’s cost structure; they merely formulate guesses based on a variety of observable variables, such as the rival’s prices and responses to the prices of competitors.

Areeda and Turner’s Marginal Cost Rule of Predatory Pricing

One of the leading treatises in the area of predatory pricing was the 1975 article by Philip Areeda and Donald Turner.63 Under the Areeda and Turner standard, pricing is predatory if it falls below the alleged predator’s short‐run marginal cost. This implies that costs above short‐run marginal costs are lawful. However, given the difficulty in measuring marginal costs, Areeda and Turner suggest that average variable costs be used as a proxy for marginal costs. Alternatives to the Areeda and Turner average variable costs rule have been put forward. These include using long‐run marginal costs as well as average total costs. Given that average variable costs are generally below average total costs, it may not be necessary to look at both, because prices that are below average variable costs should be below average total costs.64

The courts have not put forward one accepted measure of costs. For example, this issue was sidestepped in both Cargill, Inc. v. Monfort of Colorado and Matsushita Electrical Industrial Corp. v. Zenith Radio Corp. et al. Even in Brooke Group Ltd. v. Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp., the court did not have to deal with this issue; both parties to the suit agreed that the appropriate cost measure was average variable cost. Another unresolved cost issue is how to treat fixed versus variable cost. This issue includes how to deal with costs that are fixed over one time period but vary as the time period expands.

Recouping of Losses

One important result that one can derive from Brooke Group v. Brown & Williamson Tobacco is that the plaintiff must demonstrate that the defendant has a reasonable probability of recouping the losses it incurred by allegedly pricing below costs. This process involves showing that over some reasonable time period, the defendant would be able to increase price above the competitive level.65 The present value of these future profits must offset the present value of the costs incurred through the losses caused by the below‐cost prices.

The ability of the defendant to recoup initial losses caused by the predatory price can enhance the ability of the plaintiff to prove its case. This was the case in Spirit Airlines v. Northwest Airlines, Inc., when the court accepted the plaintiff’s expert analysis, which indicated that the defendant could recoup its losses quickly.66

Criticisms of the Economics of Predatory Pricing Claims

There has been much criticism of the appropriateness of predatory pricing claims. Much of this criticism revolves around whether predatory pricing can be an effective means of acquiring monopoly power.67 Some question the sense of a competitor who prices at a level where it incurs losses simply to impose losses on other firms.68 John McGee, a famous critic of rationality of predatory pricing claims, has emphasized that there are much less costly ways to obtain the same advantages that predators are seeking, such as mergers.69

In addition, he points out that once competitors perceive that the predator’s actions are temporary, they may wait out the loss period with the predator. If the actions force them to leave the industry, McGee states that they may reenter. Others have questioned McGee’s criticisms, saying that they seem accurate in theory but do not hold up when confronted with the realities of certain market situations.70 When the predator is far larger than the rivals, they may not be able to wait out the losses as easily as a well‐financed predator. In addition, rivals that were once forced out by losses incurred at the hands of a predator may think twice before devoting capital to an industry that has dealt them such unpleasant experiences. Other, more attractive opportunities may exist.

Credibility and Alleged Predation over Time

In Matsushita Electrical Co. Ltd. v. Zenith Radio Corporation et al.,71 the Supreme Court questioned the soundness of claims of predatory pricing that extended over two decades. The court concluded that it is not reasonable that any competitor would incur losses over such a long time period in the hope of recouping these gains at some indeterminate time in the future. Such a plan implies that the alleged predator is using a rather unreasonable discount rate in its competitive strategy. Ruling out such a strategy, the court concluded that the prices must be the product of normal competition. One lesson that arises from this case is that the time period over which the alleged predatory pricing occurred must be of a reasonable length. It cannot be so long as to make the claims lack credibility.

Predatory “Costing”

An interesting variant of predatory behavior is where a firm seeks to drive out rivals not by lowering their revenues through predatory pricing but by taking actions that increase their costs. Competitors that have their costs increased may reduce output, potentially allowing the predator to increase its market share.72

Price Discrimination

Price discrimination is illegal under Section 2 of the Clayton Act, which was amended by the Robinson‐Patman Act of 1936. Under the Robinson‐Patman Act it is illegal to discriminate in the prices charged to purchasers of a product where the effect of that discrimination is to lessen competition or to create a monopoly.

The theoretical basis for price discrimination is well established in basic microeconomics,73 which states that in order for price discrimination to be effective, sellers must be able to segregate customers according to their price elasticity of demand. It is also important that consumers in the relevant markets be kept separate so that product from the low‐price market does not “leak” into the higher‐price market.74 There are many examples of this type of price discrimination in practice. For instance, discount ticket buyers of airline tickets have a significantly higher price elasticity than those who seek first‐class or unrestricted coach fares.

For companies that are the victim of higher prices, their damages may be the difference between the two prices times the quantity that is determined to be the relevant amount. However, each case is different and brings with it unique circumstances that may affect this determination.

Price Fixing