CHAPTER 5

Between a Rock and a Hard Place: A Study of Megaprojects in Developing Economies

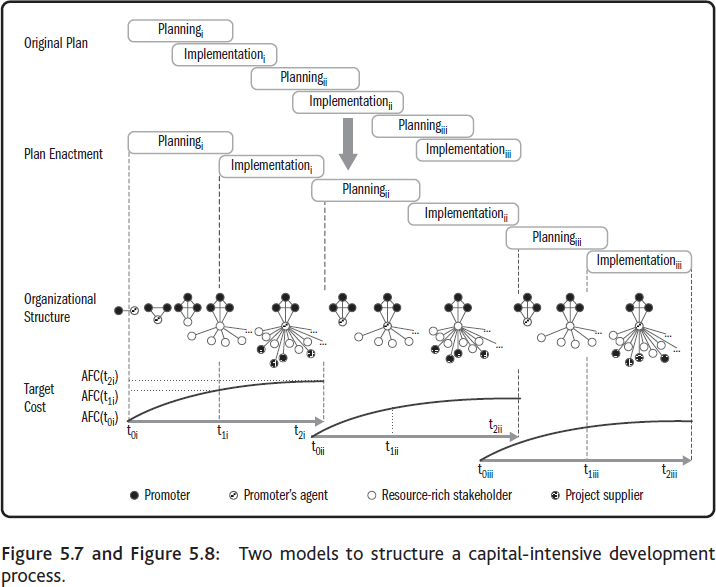

This study aims to further our understanding of the relationship between the development process and performance in developments of complex sociotechnical systems in contexts of weak institutions and scarce resources. We ground our research in a sample of capital-intensive infrastructure projects set up to address pressing needs in developing economies. Our analysis reveals two distinct approaches to structure the development process. In the sequential approach, the implementation stage is only allowed to start after planning is substantially completed. Hence, project suppliers are only procured after most critical resources are secured from independent organizational actors. In the overlapped approach, the implementation and planning stages overlap significantly after rushing buyer-supplier agreements. We find that a sequential approach attenuates uncertainty in requirements during implementation, but leads to development timescales that are wholly inadequate to the problem's urgency. In turn, the overlapped approach puts excessive faith on the ability to resolve bottlenecks through improvisation, problem-solving ingenuity, and flexibility, and thus also fails to speed up the development life cycle. We discuss the implications to literature and policy of this choice among these two unsatisfactory alternatives.

Introduction

Extant research on project-based organizations formed to develop capital-intensive systems has been informed by phenomena in advanced economies (Davies & Brady, 2000; Flyvbjerg, Bruzelius, & Rothengatter, 2003; Gil, 2007; Hobday, 1998, 2000; Hughes, 1987; Miller, Hobday, Lewroux-Demer, & Olleros, 1995; Morris, 1994). This literature presupposes that project organizations are surrounded by an environment rich in regulations, laws, and institutions that enforce a public-private divide. It also assumes munificence of management and technical skills, and other resources critical to achieve the system goal.

In Western contexts, a major challenge when developing a new capital-intensive system is to acquire critical resources up front, such as financing, regulatory consent, political support, and knowledge of needs in use. The control over these resources is distributed across multiple independent actors in the environment—the so-called “project stakeholders” (Cleland, 1986; Hobday, 1998, 2000; Miller & Lessard, 2001; Morris, 1994; Pitsis, Clegg, Marosszeky, & Rura-Polley, 2003). In exchange for committing these resources to the enterprise, these stakeholders claim rights to directly influence strategic choices. Diffusion of decision-making power leads to problems of cooperation that are intrinsic to pluralistic settings (Denis, Lamothe, & Langley, 2001; Gil & Tether, 2011; Jarzabkowski & Fenton, 2006). Resolving cooperation problems involves a search for mutually consensual plans, and the development of social norms of cooperation. Once consensus emerges, the promoter can use prices to “buy” cooperation from the suppliers who will implement the plans.

Here, we aim to extend literature on capital-intensive developments to development economy contexts. These settings suffer from multiple “lacks”—in capital, skills, and basic infrastructure networks (Hirchman, 1967); they also lack institutions for supporting markets, mediating conflicts, and enforcing the law—what Khanna and Palepu (2010) call “institutional voids.” As such, developing economies present a more complicated context for developing capital-intensive systems—it is “development on the knife-edge” (Levy, 2014). In these settings, inter-elite contestation for power and resources is strong, the normative separation between the public and the private is weak, and the use of corruption and force to appropriate private property of others is not uncommon (Levy, 2011; Woods, 2006). There is also an abundance of informal economic activity, either to seek rents by breaking the law or circumvent ambiguity in formal rules (Uzo & Mair, 2014). Furthermore, a narrow tax base, poor tax morality, and high collection costs starve the public sector of funds. And yet, once funds are acquired to finance a new development, institutional voids give the promoter potentially more leeway to do things in its own way.

A fundamental choice faced by any promoter is the decision of whether or not to overlap the planning and implementation stages. Planning is a search problem; that is, it involves searching for a solution to an existing problem. In the context of capital-intensive developments, planning is about searching for a solution that gains the support of the actors who control the resources critical for the development to forge ahead. In contrast, implementation is an execution problem; that is, it is about allocating existing resources in order to enact an identifiable solution for an identifiable problem. In the context of capital-intensive developments, implementation involves procuring and assembling a network of specialist suppliers that can be capable of transforming an existing plan into a functional designed artifact.

The choice of whether or not to overlap the planning and implementation stages in a development process is germane to management studies. Brooks's (1975) study on software development was among the first to claim that complex system developments structured as a linear sequence of phases with limited overlap (the “waterfall” model) are slow and ineffective. Subsequent studies on product development concluded that overlapping development steps and involving suppliers early on speeds up development while gaining flexibility to cope with evolving needs (Clark & Fuijimoto, 1991; Iansiti, 1995). Likewise, Eisenhardt and Tabrizi (1995) argue that experiential approaches that rely on improvisation, design iterations, real-time experience, and flexibility are advantageous to reducing the time-to-market products that are outmoded quickly. Unifying these studies is the notion that the gains in time from the overlapped approach outweigh the added costs of adapting upstream planning decisions as more information becomes available in implementation (Thomke, 1997).

The debate on the value of overlapping planning and implementation stages has extended to one-off, capital-intensive developments such as large infrastructure projects; here, the overlapped approach has three aims: (1) to compress the development life cycle, (2) to postpone commitments on downstream design choices until uncertainties in technology and user needs are resolved, and (3) to leave more time for searching mutually consensual design solutions without compromising ambitious timescales for project completion (Gil & Tether, 2011; Pitsis et al., 2003). In one-off, capital-intensive developments of designed artifacts that are hard to decompose in modular systems, however, the costs of late adaptation of the upstream design choices in response to new information emerging in implementation can be very high (Gil, 2007). Attending to the high adaptation costs of integral designed artifacts, studies on capital projects that emphasize efficiency advocate sequential state-gate processes (Cleland & King, 1968; Morris, 1994). The planning literature, too, favors a sequential approach to create more accountability for the initial pledges (Flyvbjerg et al., 2003).

Extraordinarily, this unresolved theoretical debate mirrors two distinct approaches to structure the capital-intensive development process in developing economies. Development agencies such as the World Bank and Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) rule out extreme planning-implementation overlaps. In contrast, Chinese state-owned organizations are amenable to experimental approaches. This makes developing economies a suitable setting to help us move the debate forward. To probe deeper into this research question, we built a sample of six projects to develop transport infrastructure to meet pressing local needs. The sample varies in two dimensions. First, it includes cases where the funders released financing for implementation only after planning was substantially resolved and cases where the two stages overlapped extensively. Second, we varied the context surrounding the project. Specifically, we studied projects in India, a “competitive rule-of-law state,” where political and economic rules have become impersonal, although some institutions remain weak; projects in Uganda, a “dominant discretionary state,” where political leadership has consolidated its grip on power, but most institutions remain weak and the public-private divide is blurred; and Nigeria, a country in a development trajectory between the aforementioned two (Levy, 2014).

Our inductive research produces three main contributions. First, we reveal that power diffusion over strategic choice, a structural characteristic of pluralistic settings, is central to understanding the performance of capital-intensive developments in developing economies. This claim is valid even in developing contexts, where it is arguable whether a democratic bargain is on offer. We trace the pluralistic structure of a capital-intensive development in these settings to two factors: (1) the sharing of decision-making power between cash-strapped governments and institutional funders, and (2) legal frameworks protecting property rights.

Second, we show that the propensity for slippages in the project performance targets (scope, cost, schedule) that is endemic to projects unfolding in pluralistic settings is exacerbated in a developing country. We trace this finding to two factors: (1) lack of referee structures to settle disputes (apart from inefficient court systems), and (2) the scarcity of slack resources such as budget contingencies and time buffers to reconcile incompatible goals.

And third, we illuminate the trade-offs intrinsic to the choice of whether to overlap planning and implementation or not. We find that extreme overlaps are attractive for the pledge of quick developments. In a developing country context, this approach relies on opaque cooperation, which enables suppliers to have a head start on implementation even if planning is substantially incomplete. However, the overlapped approach carries a high risk of the development process derailing if improvisation, ingenuity, and flexibility cannot resolve the bottlenecks that may ensue later on. In contrast, a sequential approach relies on substantive investment up front in planning to acquire critical resources before procuring suppliers through open tendering. The sequential approach attenuates overruns in implementation, but pledges timescales that fail to respond to the urgency of the problems.

We organize the remainder of this chapter as follows. First, we review our understanding of the relationship between development structure and performance in capital-intensive projects. We then introduce our research method and database. In the analysis, we reveal how slippages in performance targets occur irrespective of whether the planning and implementation stages overlap or not. We show that slippages occur in planning during the sequential approach, and in implementation during the overlapped approach. In the discussion, we leverage these insights to advance our understanding of the relationship between the structure of the development process and performance in capital-intensive developments. We conclude with a discussion of implications to practice and policy of this lack of a superior alternative.

Background: The Planning-Implementation Overlap in Development Processes

The development of complex systems that are made up of many interacting components can be conceptualized as a process of resolving multiple bottlenecks. That is, resolving “parts of the system that have no—or very poor—alternatives at the present time” (Baldwin, 2015). The system's bottlenecks fall into two categories. Resolving socioeconomic bottlenecks requires a combination of agreements about organizational boundaries and property rights. Resolving technical bottlenecks requires engineering technological solutions for defined problems. Both kinds of bottlenecks are intertwined. A socioeconomic bottleneck rooted in the self-interest of interdependent agents can be removed if a technical solution is found that bridges differing interests. Likewise, changes in financial arrangements or regulations can enable technological solutions that otherwise would be unviable.

Resolving some of the emerging bottlenecks in one-off, capital-intensive developments involves a search for mutually consensual solutions (Gil & Tether, 2011; Hobday, 1998; Jessop, 1997). These solutions require pooling interdependent resources that are directly controlled by independent actors. For example, resolving some of the bottlenecks in large infrastructure developments requires pooling finance, land, knowledge of needs in use, and regulatory power; these resources are individually controlled by funders, landowners, operators, and regulators (Lundrigan, Gil, & Puranam, 2015). Importantly, the problem of pooling these resources is not one that can be resolved just with transactions, because not all resources can be clearly defined, counted, and paid for (Baldwin, 2008). Rather, pooling these interdependent resources revolves around cooperation between the promoter and resource-rich actors. This cooperation hinges on letting resource-rich actors enter the development organization. Put differently, in exchange for committing private resources to a collective goal, these actors gain rights to directly influence one-off strategic design choices. This sharing of decision-making power among autonomous actors creates a pluralistic organizational structure in the planning stage. This means that many strategic choices are political, and involve both bargaining and deliberative processes (Denis et al., 2001, 2011). Once a consensual solution is found in planning, it is up to the promoter as the designated leader to “buy” cooperation from the suppliers in order to implement the agreed-upon plans.

The planning of capital-intensive systems is, however, complicated by the ambiguity in value creation that is endemic to long-lived choices. Whenever multiple claimants to single choices adopt different planning horizons, it is hard to reconcile their individual preferences (Gil & Tether, 2011; Ostrom, Gardner, & Walker, 1994). Matters become more complicated because the ambiguity endemic to long-term developments makes it hard to develop robust social contracts, a coordination mechanism that requires goal clarity and mutual credibility (Gibbons & Henderson, 2012). In these pluralistic settings, the risk is therefore high that indecision will escalate and controversies will drag on unresolved for a long time (Denis, Dompierre, Langley, & Rouleau, 2011). Furthermore, disputes over the evidence that various parties produce to back up their claims can lead to the risk of inaction and reversal of choices that were previously agreed upon—what Langley (1995) calls “paralysis by analysis.”

When strategic choice is political, it is tempting to overlap the planning and implementation stages. The reason is that if the two stages overlap, as planning choices move into implementation, the cost of reversing the planning choices escalates. As the adaptation costs increase, it gets more difficult for other actors to demand late changes. Overlapping planning and implementation can also be attractive to create an option to achieve the end goal faster (Gil & Tether, 2011). Furthermore, rushing planning to start implementation work leverages what Hirchman (1967) calls the “hidden hand principle”—this is the idea that inadequate planning and utopian visions enable people to misjudge the nature of the tasks and underestimate the real costs. This is helpful in offsetting people's tendency to underestimate the problem-solving power of creativity, ingenuity, and flexibility; as Hirchman (1967) puts it, “the hiding hand is essentially a way of inducing action through error” (p. 28).

However, a decision to progress a capital-intensive development into implementation when strategic choices are unresolved creates high uncertainty in the requirements. If the system is hard to decompose, this uncertainty increases the risk of high adaptation costs, and impairs the production of reliable cost and/or schedule forecasts (Morris, 1994). High uncertainty also makes planning vulnerable to promoter's optimism bias, and to deliberate misrepresentation of the socioeconomic value of the enterprise (Flyvjberg et al., 2003).

Given these downside risks, the choice to overlap planning and implementation in capital-intensive developments is regulated in Western contexts especially in publicly financed schemes. In the United Kingdom, for example, any major public infrastructure project can only start after the land is acquired and a planning application approved. Regulation is enforced by a system of “referees” or “umpires” (e.g., courts, public inquiries, parliamentary committees) that are empowered to settle disputes. Capital-intensive private industries enjoy more flexibility to overlap planning and implementation tasks insofar as the promoter stays within legal rules and regulatory frameworks. For example, extreme planning-implementation overlaps are the norm in developments of semiconductor fabrication facilities. For chipmakers, the potential benefit of reaching the market first with a new commercial product way outweighs any adaptation costs stemming from the concurrent development of new chips and the factories where the chips will be made (Gil, Tommelein, & Schruben, 2006).

In developing economies, the overlap between planning and implementation in capital-intensive developments is much less regulated (Brautigam, 2011; Hirchman, 1967; Levy, 2014). Hence, once the financial bottleneck is resolved, the environment will let the promoter choose whether to overlap planning and implementation or not, given urges to solve the problem. We turn now to discuss how we set out to explore alternative ways to structure the development process by looking at urgent infrastructure projects in developing economies.

Research Design, Sample, and Methods

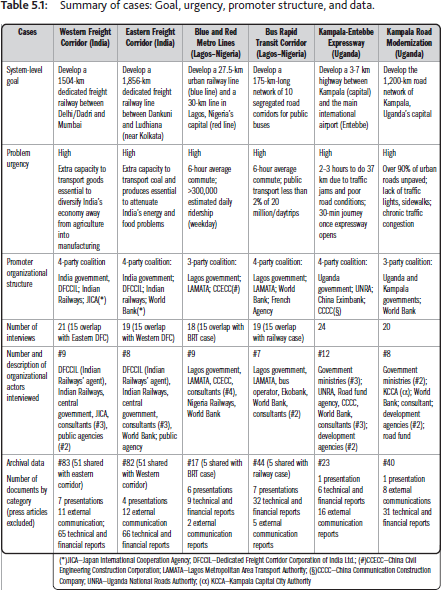

As mentioned, our research is inductive and follows a multiple-case study research method (Eisenhardt, 1989; Yin, 1984). Our cases consist of capital-intensive infrastructure development projects created to meet an urgent local need. Our sample varies in two dimensions. First, we varied the source of financing. This was important to include cases of extreme planning-implementation overlap (enabled by a constellation of Chinese actors) and cases with a sequential approach to development (enabled by the World Bank or JICA). Second, we varied the context. New infrastructure projects involve vast sums of money, which makes them vulnerable to illegal activity—the more so, the more fragile the institutional environment is. Embezzlement of funds, corruption, and fraud could thus explain slippages in performance targets. To control for this, we included projects in Uganda, a dominant state (so-called “big-man rules”) where disparity between the power of the rulers and opponents is large and the public-private divide is weak; India, a “rule-by-law” state where politics is more competitive and impersonal, even if other aspects of democratic sustainability are yet to be achieved; and Nigeria, a country in which the legal and political system falls in between the two (Levy, 2014). (In the 2014 Transparency International corruption perception index for 175 countries, India ranked 85; Nigeria, 136; and Uganda, 142.) Table 5.1 summarizes, for each case, the system-level goal, the urgency of the local problem, the organizational structure of the project promoter, and the data sources.

Data Collection

Data collection started in 2013 and lasted two years as part of an independent research study to extend our understanding of capital-intensive developments to contexts with weak institutions. We adopted two approaches to gain access to data. In the case of India, we cold-called the chief executive of the public agency formed to develop a new railway system—the Dedicated Freight Corridor Corporation of India Ltd. (DFCCIL)—who gave us access to the research site. In the other cases, we collaborated with civil servants who were on study leave at our university. One graduate student–cum–civil servant helped us gain access to the top management team of LAMATA, the public agency set up to modernize the transport infrastructure of Lagos, Nigeria's capital; another graduate student–cum–civil servant helped us gain access to the top management teams of Uganda National Roads Authority (UNRA), the public agency leading the development of the Kampala-Entebbe Expressway in Uganda, and the Kampala Capital City Authority, the local government of Kampala, Uganda's capital.

In all cases, we adopted a snowball approach (Biernacki & Waldorf, 1981) to develop our database. Hence, for each case, we systematically asked the first respondents to introduce us to other relevant actors. In this way, we successfully interviewed multiple organizational actors, including funders, consultants, contractors, public agencies, and government departments. Through one- to two-week visits to each site, we conducted 91 formal interviews up to two-hours-long each; we tape-recorded all interviews. We conducted follow-up interviews by phone and email. We were not asked to sign nondisclosure agreements, but were asked not to use particular quotes. To gather extra data and allow for member checks (Lincoln & Guba, 1985), we shared factual and chronological accounts with the respondents. In the Uganda and Nigeria cases, we also produced hand-recorded verbatim notes of the informal chats we engaged with during three-hours-long visits to the construction sites.

To improve data accuracy and the robustness of the insights (Jick, 1979), we triangulated the verbal accounts against archival data (Miles & Huberman, 1984). The public agencies promoting the developments shared with us technical and financial reports, PowerPoint presentations, and articles published in governmental publications. We complemented this information with a wealth of information found online. First, the projects funded by the World Bank and JICA are well documented online. Key documents supplied by the funders include technical reports assessing the schemes’ viability and progress reports. There is limited information publicly available on schemes financed by the Chinese actors, but all the developments were closely monitored by the local presses (in English), particularly in terms of announcements of performance targets, achievement of milestones, and land disputes. To encounter relevant articles, we googled the names of the top management staff and elected politicians who were directly involved in the new infrastructure developments.

Methods

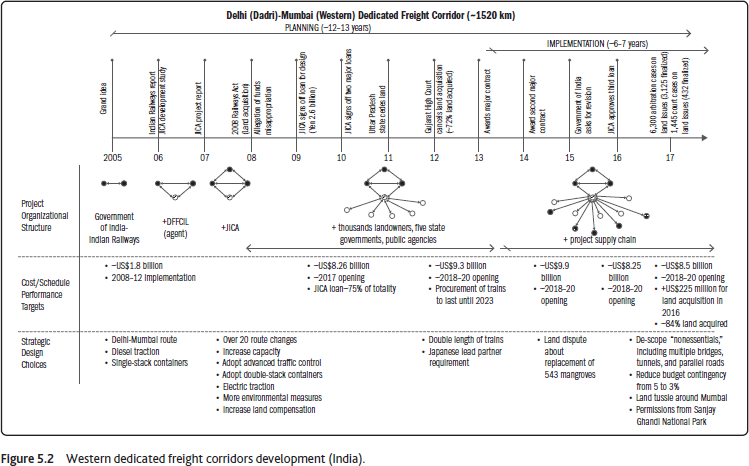

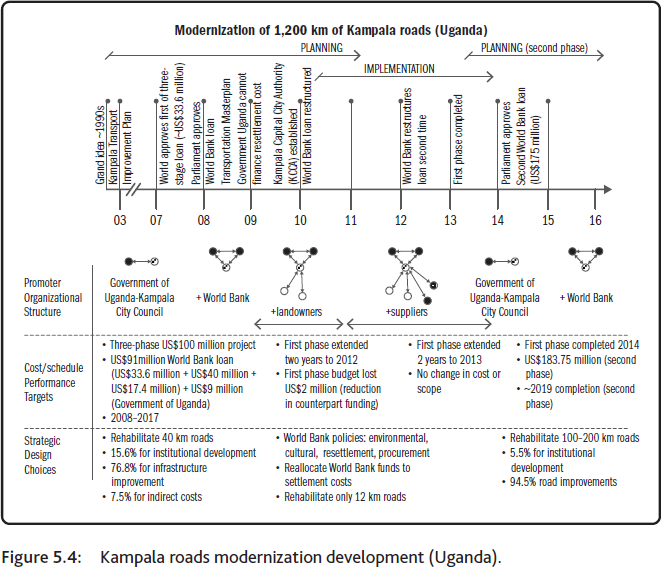

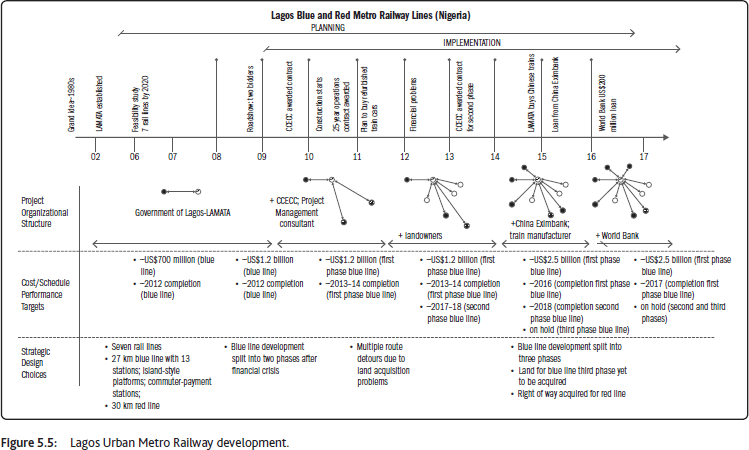

Following recommendations for inductive reasoning (Ketokivi & Mantere, 2010; Langley, 1999), we started our analysis by producing detailed chronological and factual accounts for each case to guard against account bias (Miles & Huberman, 1984). We then analyzed the data using coding and tabular displays (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). In addition, we developed stylized maps of the development life cycles. In each map, summarized in Figures 5.1, 5.2, and 5.3, we captured the evolution of the developments along three dimensions: strategic design choices, organizational structure, and performance targets (cost, schedule, scope). As we iterated between reviewing data, constructing the development life cycle maps, and theory-building, an argument emerged suggesting two distinct approaches to achieving system-level goals. We called them the sequential and the overlapped approach to recognizing the variance in the extent to which planning and implementation tasks overlap. We continued to iterate between data analysis and conceptual development until we reached theoretical saturation. We now present our analysis and then discuss the contributions to literature and policy.

Analysis

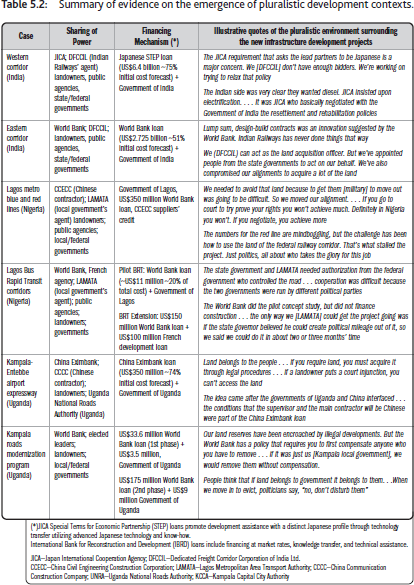

We organize our analysis by first discussing the root causes of pluralism in our sample of new infrastructure development projects in developing economies. With pluralism as a backdrop, we then analyze the structure-performance relationships. We trace evolution in performance to evolution in the project organizational structure and differing structures of the development processes. The development life cycle maps for the six cases represented in Figures 5.1, 5.2, and 5.3, and the excerpts of data in Tables 5.2 and 5.3 illustrate the analysis that follows.

The Emergence of Pluralistic Developments in a Developing Economy

A pluralistic structure boils down to power-sharing across multiple independent actors with conflicting goals. In these settings, the heterogeneity of belief systems, knowledge bases, and ideologies makes it hard to set up a meritocracy-based authority to resolve disputes (Denis et al., 2001, 2011). In turn, the distribution of resources impedes a dominant coalition to impose their preferences on others, as it happens in hierarchical organizations. Hence, in a pluralistic setting, many strategic choices involve bargaining processes that are informed by cost-benefit evidence produced by the technocratic teams of the disputants.

Across our sample, we regularly observed the emergence of a pluralistic structure at the onset of the development processes. Table 5.2 summarizes the evidence. We traced pluralism to two main factors. First is the interdependency between the promoter and the funders. This occurs because governments in developing economies are cash-strapped and struggle to borrow money; private actors also shy away of capital-intensive investments because they are wary of what might happen once the project is completed and the bargaining power shifts to government (Vernon, 1977). It is within the remit of international development agencies to finance capital-intensive infrastructure, but agencies are not altruistic and are accountable to many principals for capital spending. Hence, they want to directly influence strategic choices.

The cases of India's two dedicated freight corridors, illustrated in Figures 5.1 and 5.2 and Table 5.3, are telling. The development of six railway lines (golden quadrilateral) dedicated to freight was idealized around 2005 between the government of India and Indian Railways, the public agency in charge of railroads. The idea was spurred by a sense of deep crisis. By then, the country's Victorian railroads were operating far above design capacity and had lost 50% of the lucrative freight transportation to the roads. This shift had left the main roads chronically congested; it was also undermining the viability of Indian Railways, which relied on freight tariffs to cross-subsidize some of the lowest tariffs worldwide for railway passengers; one public official said:

Railways are India's lifeline…. Everybody looks at this [dedicated freight corridors] as a national thing. People will be questioning if the project is slow or why it cannot be done faster. But there are no opponents…the project is needs based.

Resolution for the financial bottleneck emerged in 2007 when the government of Japan agreed to finance three-quarters of the forecast cost of the western corridor. But it would be a tied loan under the Special Terms for Economic Partnership (STEP), and thus there would be strings attached. And indeed, JICA suggested multiple changes to strategic design choices made by Indian Railways, including: (1) moving from diesel to electric traction, (2) increasing the capacity of the train cars, and (3) adopting a minimum of 30% of Japanese technologies. When the World Bank warmed up to the idea of financing two-thirds of the initial forecast cost for the eastern corridor, more changes ensued. Specifically, the World Bank asked DFCCIL (the semi-autonomous agency set up by Indian Railways to develop the project) to adopt the bank's policies on environment, procurement, and land acquisition. During the five years that it took to complete the negotiations for both loans during planning, the performance targets evolved, as summarized in Figures 5.1 and 5.2 and Table 5.3.

The second major source of pluralism was the local politics around land acquisition. Across our sample, it fell on governments to directly finance the costs of land acquisition. Local laws empowered the governments and their agents to compulsorily buy land, but taking land was a sensitive issue: Many landowners either did not want to move out or demanded more compensation than what was on offer. Land disputes were quick to make headlines in the local press and often became political footballs. To avoid disputes that drag on unresolved for years in the court system, the promoters sought major detours for the routes. If detours were not an option, the promoters faced lengthy negotiations to acquire the land.

One good example is the case of the 37-kilometer expressway linking Kampala, Uganda's capital, to the main international airport in Entebbe, illustrated in Figure 5.3 and Table 5.3. The project was urgent for the socioeconomic development of Kampala, a city with around 1.8 million people (half of the country's urban population) and responsible for half of Uganda's GDP. The 37-kilometer car journey between Kampala and the airport could easily take three hours during the day. And yet, the project suffered many setbacks as disputes with powerful landowners emerged throughout implementation. In some cases, the cash-strapped promoter moved the planned route to avoid paying exorbitant compensations to landowners (in its view). In other cases, the promoter pragmatically started to implement the sections of the highway to the right and to the left of the land yet to be acquired as it waited to resolve the bottleneck.

Systematically, our findings suggest that the escalation in performance targets, because of difficulties in resolving land disputes, was exacerbated by the lack of slack resources and by ineffective referee structures. Slack resources such as budget contingencies enable incompatible goals to be reconciled without resolving conflict (Cyert & March, 1963). In the United Kingdom, for example, the budgets for complex developments have very large funding contingencies built in at the onset of planning. These contingencies create a buffer to help finance concessions to disputants while keeping the budget stable. But in our cases, the funders ruled out any idea of financial slack. To make matters more complicated, we did not encounter any umpiring structure to help resolve disputes, apart from the ineffective court system. Hence, dispute resolution could take years, creating a dilemma as to whether to overlap planning and implementation or not. We now analyze two approaches to address this dilemma.

Improvisation Under Extreme Planning-Implementation Overlap

The decision to overlap planning and implementation in capital-intensive developments is not uncommon. This approach recognizes that the processes necessary to acquire different resources critical to achieve the system goal unfold at different speeds. The speed at which promoter and other actors can strike a consensus also varies across the strategic design choices that they need to agree upon. Overlapping planning and implementation helps to move parts of a development into implementation while allowing more time to resolve other problems. But if the parts that move first into implementation are interdependent with those yet to be resolved, the overlapped approach increases the risk of rework (Gil & Tether, 2011).

In our sample, the two schemes with major involvement of Chinese actors regularly embraced an extreme overlapped approach. In both of these cases, implementation started soon after a buyer-supplier agreement was forged at closed doors. This approach leveraged suppliers’ credit for a grace period and land that was already under the control of the promoter. It also trusted the promoter's capacity to flex and improvise to eliminate any bottlenecks that could emerge later on because of lack of cooperation with other resource-rich actors, notably landowners that were refusing to part with their land. However, our analysis suggests the promoters and suppliers were systematically overly optimistic about the capacity of improvisation, ingenuity, and flexibility to resolve emerging bottlenecks. Indeed, our findings show that the two cases in our sample that adopted an extreme overlapped approach derailed after complicated bottlenecks emerged. Another cost of this approach was a lack of transparency around the buyer-supplier deals. One Nigerian official explained:

We put the cart before the horse and start building stuff without a translated design from Chinese…the fact they [CCECC] are owned by the China government helps them to be very competitive…they just want to sort out your problems and do the work…they don't mind “getting their hands dirty” [if you will] as long as the business case works for them.

A good example is Uganda's Entebbe-Kampala Expressway, illustrated in Figure 5.4 and Table 5.3. Only a constellation of Chinese actors expressed interest in attempting to rapidly resolve this problem. To speed things up, the Uganda government, the Uganda National Roads Authority (UNRA), and the China Eximbank agreed on a concept design and cost and schedule targets behind closed doors. As part of the US£350 million loan (two-thirds of the initial cost forecast), the contract was awarded to the Chinese firm CCCC with no bid arrangements. This was a controversial decision because CCCC had been recently blacklisted by the World Bank for corruption, and the constitution prescribed competitive bids for major procurement contracts. The deal also relied on changing the laws that prohibited toll roads.

Once implementation started, disputes emerged around private land. To speed up construction and bring costs down, CCCC designed the route to go through a stone quarry from which it planned to extract stone. But the plan backfired after the owner rejected the compensation—“part is greed, part is legal issues. Uganda law doesn't favor development, but we've to work within the law,” said a CCCC manager. With the government cash-strapped and no efficient mechanism to resolve disputes, the dispute dragged on unresolved. Implementation progressed by improvisation at the expense of efficiency and effectiveness. Where possible, the route was changed to avoid land difficult to acquire. And if detours were not possible, construction progressed upstream and downstream of the parcels of land yet to be acquired. On a positive note, the Parliament succeeded in changing the law necessary to make the road a toll road, disarming the cynics who had argued it would never happen.

The case of the blue metro line in Lagos, illustrated in Figure 5.5 and Table 5.3 provides a second example of improvisation under extreme overlap. The scheme was part of a 2018–2020 vision for the city developed in 2006 by LAMATA, a public agency sponsored by the World Bank and set up to tackle the transportation problems of Lagos. The city of almost 20 million people was forecasted to become Africa's largest city by population in a few years’ time, but it still lacked the most basic public transportation. People relied on an incipient road network and informal buses (danfos and molues) to move around, and six-hour daily commutes were the norm. The 2018–2020 transport vision included six railway lines; for LAMATA, it was a priority to first develop two rail lines: the blue line, for which local government controlled some land, and the red line, which would run along an existing federal railway corridor. In 2009, LAMATA awarded a contract to develop the blue line to CCECC, a Chinese firm, after a tender for which only two firms qualified. CCECC started implementation one year later on suppliers’ credit for a grace period. Getting this line done was critical for LAMATA officials; as one official said:

Nobody thought about rail for Lagos…nobody would say, “can we dare to do this?”…the first time we [LAMATA] told the Lagos state commissioner that we needed a railway, he laughed and said, “Come back to the earth. You guys are in the clouds.”

Implementation of the blue line started concurrently with the processes to acquire the land and the finance necessary to start paying back CCECC once the grace period of the supplier's credit expired. As implementation progressed, improvisation ruled. First, the route was changed after the military refused to sell some critical land. Then a third of the line was put on hold after the federal government demurred to supply another parcel of critical land. Although it was a struggle to find financing to start paying CCECC, implementation continued to bumble along. In 2015, the promoter secured a loan from the World Bank, creating expectations that a first small section would open by 2017–2018. More frustrating for LAMATA has been the failure to acquire federal land and financing for the much-needed red line (favored by the World Bank) after more than 10 years of talks. In this environment, LAMATA officials appreciated the Chinese approach to development; one official said:

Let me give you a good thing about CCECC…they are really ready to deliver and satisfy their clients…. When you award them a particular contract it takes less time for them to start construction and mobilization…. They won't say “the government isn't paying, I won't work.”…I think it's one of the reasons for the success of the Chinese companies in Africa.

We turn now to analyze the sequential approach to capital-intensive developments.

A Linear, Sequential Approach to Capital-Intensive Developments

A linear, sequential approach to capital-intensive developments is an alternative model to structure capital-intensive developments. The advocacy for this model can be traced to social norms rooted in the project management profession, which emphasizes scope freeze and control systems over flexibility (Lenfle & Loch, 2010). From this perspective, projects that miss the initial performance targets “fail,” which impairs professional careers. These norms shape action in agencies such as the World Bank and JICA, and these funders do not disburse funds until they are confident that the implementation can unfold as planned.

One good example is the case of the development of rapid bus corridors in Lagos, illustrated in Figure 5.6 and Table 5.3. When the World Bank sponsored the establishment of LAMATA in 2006, the idea to develop 10 segregated busways gained wide support. The plan was to complete the 173-kilometer network by 2020. But first, the World Bank insisted on building Western organizational capabilities—“we felt there was a need to create an agency that was appropriately structured to drive the level of transportation in Lagos,” said one official. Concurrently, the bank agreed to finance the design of a pilot corridor, which opened two years later in 2008. But then things slowed down dramatically. It took four years of cooperation to acquire financing and land to implement a 14-kilometer extension of the first BRT corridor during which the cost forecast doubled. The implementation stage stayed largely within budget, but took three years instead of two. Though the World Bank argues that LAMATA is a “beacon of good public management in a dark place,” it is unclear if and when the whole vision will be achieved—“one corridor is better than nothing,” said one World Bank official.

The case of the six dedicated freight corridors in India, illustrated in Figures 5.1 and 5.2, offers a second example. The initial 2007 plan was to open the first two corridors by 2012. The idea was well received by JICA and the World Bank, conditional on sequential developments. Both funders ruled out disbursing any funds for implementation before 80% of the land was acquired. The funders also suggested breaking each corridor into multiple smaller sections that could be planned and implemented sequentially. Planning for the first sections of each corridor took between four and six years. In addition to difficulties in acquiring the necessary land and regulatory consent, the funders introduced rigid policies to procure suppliers, further delaying progress. Delays notwithstanding, a sequential approach created greater certainty in implementation. The latest forecasts suggest moderate slippages in the cost targets; the two corridors are due to open partially in 2018, but it is unclear when they will be fully completed. As for the other much-needed corridors, they remain a “dream on paper,” as one officer said.

The case of the road improvement project in Kampala (illustrated in Figure 5.3) provides a last example. The urgency to improve the roads of Kampala was indisputable. In 2007, the population was projected to grow at 4% annually and 1.5 million people entered the city daily. But less than 25% of the roads were paved, and the paved roads had hardly been maintained since the 1940s. To move faster, people relied on informal motorcycle taxis (boda-bodas) that could snake through gridlocked traffic and potholed roads. But boda-bodas were dubbed the “silent killers” because of the thousands of accidents and fatalities they caused every year. The road modernization program started in 2007, when the World Bank signed off on a US$33.6 million loan to support the first phase of a three-phase program to modernize Kampala in 10 years; the approach was sequential, as explained by one official:

The project was conceived as the first of a three-phase Adaptable Program Loan to provide support for the implementation of Kampala's long-term development program, which would require step-by-step policy reform and institutional development over a sustained period.

The first phase revolved primarily around planning and building in-house capabilities ahead of implementation. Investments thus went to develop a land-use database, reform financial and fiscal services, liberalize service provision, and develop the organizational capacity of the local government. But this phase encountered multiple setbacks and took seven years instead of three to deliver. In this period, the World Bank helped improve 12 kilometers of roads, a far cry from the initial plan to rehabilitate 26 kilometers of tarmac roads and 14 kilometers of unpaved roads. Still, by 2014, Kampala was a city “on the rise” in the World Bank's view, even if the traffic problems had worsened as the population had grown at 5% annually and more people were on the roads with the arrival of online marketplaces to buy used cars. A second five-year, US$175 million phase was launched by the World Bank in 2014, allocating 90% of the funds to improve the roads, and assuming the use of public funds to acquire land. The aim was to upgrade between 100 and 200 kilometers of the city roads by 2020. But skepticism has mounted about the realism of this goal; one respondent said:

The difficult part is determining the land values [and] whether certain people are eligible or not…everyone, irrespectively of whether they settled in the road reserve or not, wants compensation…for the World Bank, whoever is being deprived of a livelihood should benefit. Yet government thinks that if you settled in the road reserve you shouldn't get compensation.

All in all, our analysis suggests two very different approaches to structure capital-intensive developments under conditions of urgency and resource scarcity. One approach allows for an extreme overlap between planning and implementation. This approach is attractive for the pledge to speed things up, but it carries major costs. First, it lacks transparency over the cooperation that led to buyer-supplier deals; and second, it cannot offer any certainty that performance pledges will be met if improvisation, ingenuity, and flexibility cannot resolve bottlenecks created by lack of cooperation among the promoter and resource-rich actors.

The attractiveness of the second approach, which is linear and sequential, is more stability in the performance targets during implementation and the safeguards built in against graft. But the time it takes to resolve disputes with resource-rich local actors—a prerequisite to start the capital-intensive implementation—is a major disadvantage from the perspective of the promoter. Importantly, a sequential approach attenuates, but cannot eliminate, slippages in targets during implementation. For example, the lack of enforcement structures and common knowledge that funds have been committed to acquire land both create real risks that land acquired during planning may be occupied by squatters or seized illegally or fraudulently by predators. On balance, it seems fair to say that benevolent local promoters who are genuinely eager to solve local problems find themselves between a rock and a hard place.

Discussion

We return now to the research question central to this chapter: whether to overlap planning and implementation in capital-intensive developments of complex systems. The overlapped approach is rooted in studies of high-speed environments (Eisenhardt & Tabrizi, 1995; Iansiti, 1995). In these settings, the gains for products that reach the market first outweigh the adaptation costs. Furthermore, “nearly decomposable” design structures dampen the cost of delayed commitments and design iteration (Baldwin & Clark, 2000; Simon, 1962).

In contrast, there is no consensus over the value of the overlapped approach in capital-intensive projects. Because of their scale, these developments cannot forge ahead unless the promoter and autonomous development partners cooperate in planning. But if multiple actors with rivalrous preferences share decision-making power over strategic design choices, the final choices need to be mutually consensual (Gil & Baldwin, 2013). Hence, the promoter's capacity to reliably predict the outcome of the planning talks is limited. Complicating matters, in capital-intensive developments, physical constraints make it hard to decompose the design structures into modules, and thus isolate upstream systems (the first to move into implementation), from the downstream systems. The overlapped approach encourages forging ahead with the implementation of upstream systems concurrently with planning talks for interdependent downstream systems. This creates a high risk of rework of the upstream systems if the downstream planning talks resolve unfavorably. Hence, a research strand that emphasizes control, efficiency, and reliability argues that the overlapped approach leads to rework, delays, and a deficit in accountability (Cleland & King, 1968; Flyvbjerg et al., 2003; Merrow, McDonwell, & Arguden, 1988; Morris, 1994). In contrast, research that emphasizes effectiveness argues that this approach permits development to speed up without forcing premature commitments (Miller & Lessard, 2001; Pitsis et al., 2003). For example, a “Last Responsible Moment” policy enabled to start the construction of Heathrow Airport Terminal 5 while the design of the downstream systems was still unresolved (Gil & Tether, 2011). The lack of comparative studies has made it hard, however, to further this debate.

Here, we attempt to move the debate forward by, first, factoring in the evolution of the project organization structure into a comparative analysis, and second, by casting a wider net over the development life cycle. Figures 5.4 and 5.5 conceptually illustrate in a stylized way the two alternative structures’ development processes. It is not our task to contrast the two approaches in terms of robustness to illegal acts. These problems are endemic to developing economies and are not the preserve of a particular approach to development. They are also difficult to research because, as Brautigam (2011) puts it, “how often will people readily admit the existence, let alone the size, of kickbacks and embezzlement?” And indeed, during our fieldwork, we encountered problems with artificial inflation in prices and fraudulent land acquisitions across the spectrum. More to the point of this chapter, we shed light on the strengths and weaknesses of the two approaches to development under pluralism.

In pluralistic structures, many strategic choices are intrinsically political (Jarzabkowski & Fenton, 2006). Hence, strategic choice relies on seeking consensus through negotiation and bargaining informed by evidence assembled by technocratic teams. This makes pluralistic settings vulnerable to cycles of making, unmaking, and remaking strategic choice (Denis et al., 2011). The risk of doing nothing is also high if people refuse to compromise and reciprocate. Under these circumstances, mechanisms that increase the cost of reversing decisions make it more difficult for actors to withdraw their commitments without losing face. From this perspective, the high costs of reversal under the overlapped approach are advantageous to mitigate the risk of defection in planning driven by uncooperative behavior.

The cases of the Kampala-Entebbe Expressway and the Lagos blue metro line illustrate the capacity of the overlapped approach to get the ball rolling. Although both projects aimed to resolve pressing problems, the local actors were scrambling to get them off the ground. What the overlapped approach did was sidestep the risk of impasse by restricting the up-front negotiations to a selected few resource-rich actors. By deliberately excluding multiple claimants from the decision-making process, cooperation emerged between a tightknit constellation of Chinese organizations and the leading local actors. This occurred regardless of whether the buyer-supplier agreement was negotiated behind closed doors (the Kampala-Entebbe expressway case) or preceded by open tendering for a basic concept (the Lagos blue metro line case). With a buyer-supplier deal out of the way based on a rudimentary concept, the implementation stage could start and the development process became harder to reverse.

However, in agreement with extant studies going back to Morris and Hough (1987), the risk that a capital-intensive development may unravel under this experimental approach is high. This structure relies on flexibility, ingenuity, and improvisation to resolve any socioeconomic bottlenecks that emerge later on. To avoid impasse over property rights or organization boundary issues, the promoters can adapt the design choices; they can also change the implementation sequence to gain time to resolve disputes without compromising deadlines. In extremis, plans to develop downstream parts of the system can be put on hold if a consensus cannot be struck. But as Figure 5.4 suggests, the capacity of the overlapped approach to achieve the system-level goal faster in a pluralistic structure is illusive. This approach also has no capacity to produce reliable targets up front and deliver on its pledges.

Crucially, however, a sequential approach is disappointingly slow in getting things done. The basic idea here is to first break apart a complex system into multiple parts that can be developed sequentially. By adopting a stage-gate model, planning to develop one part needs to be substantially done (but not completed) before starting implementation (Cooper, 1990). The underlying assumption is that the requirements can be specified in advance of requesting bids to implement the plan (Brooks, 1975). Under pluralism, however, there is no authority or meritocracy-based hierarchy to resolve disputes; market mechanisms are also insufficient to acquire all the critical resources necessary to resolve planning problems. Hence, building consensus over subsets of planning decisions becomes a prerequisite to progress each development phase into implementation. As one phase of planning is resolved and moves into implementation, consensus seeking must start for the next phase, and so forth.

Our findings reveal, however, an optimism bias up front regarding the time and effort it takes to build multiple consensuses under a sequential approach. As a result, the initial plans work as “pseudo comprehensive” plans (Hirchman, 1967) in that they pretend to have more insight into the ensuing difficulties than they actually have. As planning activity drags on and the cost forecast escalates, the risk increases that strategic choices will be unmade because the cost of reversing a choice is low. The cases of the Kampala road modernization and the Lagos busways illustrate how a sequential approach struggles to get things done. In both cases, there was consensus that the schemes were urgent. And yet, attempts to resolve planning for even a small fraction of the system-level goal turned out to be frustratingly protracted. As the initial costs and schedule targets gradually slipped, parts of the scope were abandoned. This led to a growing sense of disappointment in the eyes of third parties. This is not to say that an overlapped approach could have done it faster. But it is important to see the slowness and limitations that are endemic to a sequential development approach in order to understand the attractiveness of the pledges of the overlapped approach to the local actors.

Between a Rock and a Hard Place

If we cast a wide lens over the development life cycle, we cannot argue that the overlapped approach is superior to the sequential approach or vice-versa in terms of getting things done fast and offering reliable outcomes. The difference between the two lies in the stage of the development process in which the performance slippages occur. In the overlapped approach, as Figure 5.4 shows, strategic design choices occur before many resource-rich actors enter the core structure of the project-based development organization. By excluding these future claimants from the decision-making process, this approach fuels a self-serving optimism that amplifies its own attractiveness. As implementation unfolds and the claims of resource-rich actors upend strategic choices, the performance targets need to adapt. Setting new targets is a protracted process that requires cooperation both with the resource-rich actors as well as with the suppliers. In contrast, in the sequential approach, substantial slippages in the performance targets occur during the up-front search for mutually consensual solutions with resource-rich actors (Figure 5.5). However, once a buyer-supplier agreement is negotiated, fewer slippages in the performance targets can be expected to occur.

In our sample, the cases with extreme overlaps show high escalation of performance targets throughout implementation. The US$476 million Entebbe-Kampala Expressway was scheduled to open in 2016 when implementation started, but the latest forecast suggests a 2019 opening date and unknown costs; likewise, the costs of the Lagos blue metro doubled during implementation despite a major reduction in the project scope and a five-year delay. The performance of the sequential developments is equally disappointing. For example, only one busway is done to date, out of a plan to develop 10 bus corridors by 2020 in Lagos; and it is a dream yet to come true to see the completion of the much-needed India golden quadrilateral or the paving of Kampala roads. But our analysis does not trace the slippages in the performance targets of the sequential developments to insufficient time spent in planning. In both cases, the schemes have dwelled in planning for many years. Rather, slippages are rooted in a failure to build consensus within a rigid development structure that puts no trust in the capacity for improvisation, creativity, and flexibility to resolve the system's bottlenecks.

Of course, the opaqueness of the buyer-supplier deals that enable the overlapped approach is at odds with Western professional norms. This opaqueness cannot be eliminated, however, because it is a prerequisite to enact this approach. Covert deals make it harder for resource-rich actors to contest announcements of strategic choices because they lack the data to contest. And yet, our study suggests that murky deals often backfire because they cannot muster the resources necessary to resolve bottlenecks that emerge later on. Furthermore, the costs of modifying strategic design choices in implementation to overcome emerging bottlenecks then raise the threat of opportunistic behavior by the supplier (Stinchcombe & Heimer, 1985; Williamson, 1993). Once implementation has started, replacing the supplier in one-off developments is not trivial. This creates a risk; the supplier might demand far more favorable new terms by threatening not to adapt the work plan. However, it is speculative to suggest that better results could be achieved by adopting a sequential approach instead. We cannot presuppose that a sequential approach would ever be able to encourage sufficient cooperation between the promoter and development partners to progress development.

Complicating the adoption of both approaches is the lack of devices for integrating effort between the promoter and development partners in developing economies. First, there is a lack of slack resources. Organizational slack is useful for reconciling incompatible goals without resolving conflict, what Cyert and March (1963) call “quasi-resolution” of conflict. Funding contingencies enable side payments without compromising budgets, and time buffers allow more time to build consensus without compromising deadlines. But in developing economies, financial resources are scarce; time is also a scarce resource, given the urgency of the problems. Second, there is a lack of affordable conflict-resolution mechanisms—a precept of robust arenas of consensus-oriented collective action (Ostrom, 1990). Aside from inefficient court systems, we did not encounter any external referees empowered to settle disputes. And third, a lack of transportation infrastructure and chronic traffic gridlocks make it costly to engage in face-to-face interaction, an essential communication channel to resolve disputes (Ostrom, 2005). Unresolved disputes—especially around land issues—were thus a major source of performance slippages in both approaches.

In sum, we cannot argue that, in a pluralistic organizational structure, the overlapped approach to structure capital-intensive developments is superior to the sequential approach, or vice versa. This has been, however, the underlying tone of the scholarly debate. Rather, our study suggests that both ways of structuring the development process have advantages and disadvantages. This finding resonates with the notion of equi-finality in complex systems theory, which argues that in open systems similar results can be achieved with different initial conditions and in many different ways (Bertalanffy, 1968). A capital-intensive development has many direct interactions with resource-rich actors in the environment, and thus is an open system. These actors need to contribute individually owned resources in order for the project to forge ahead, meaning that they are de facto development partners of the promoter (Lundrigan et al., 2015). Different development structures show distinct ways to achieve the system-level goal, but building consensus remains a prerequisite to resolve the bottlenecks.

Policy and Practice Implications

Our insights have important implications to public policy and practice. The development of capital-intensive infrastructure in developing economies is a pressing issue. The United Nations (2011) forecasts that most of the global population growth up to 2050 (~2.5 billion) will occur in developing economies. The lack of basic infrastructure in developing economies will exacerbate asymmetries with advanced economies, and create global challenges. This suggests that we want to understand better alternative approaches to capital-intensive developments in these settings. Our study reveals that opaque cooperation between promoters and suppliers suffices to rush planning for capital-intensive developments in contexts of weak institutions and scarce resources. This “mutual benefits” (Brautigam, 2011) approach resonates with Hirchman's (1967) claim that taking more risks is a good way to undercut people's propensity to underestimate the strength that is left in them to tackle difficult tasks. Hirchman traces this propensity to the lack of a tradition in problem solving, innovation, and invention in developing economies—hence, rushing planning works as a “crutch” to help move things forward. However, our study suggests that this approach is overly optimistic. In pluralistic settings, even if institutions are fragile, skills and creativity can be insufficient to resolve emerging planning problems, and developments can then derail. And yet, a sequential approach to development that relies on prearranged dovetailing of tasks and detailed planning to coordinate future action is also frustratingly ineffective.

Interestingly, this choice between two “evils” mirrors a policy debate about how to engage with development economies. As Brautigam (2011) argues, the “Chinese approach” mirrors what the Chinese policymakers learned through similar deals that Japan and the West offered China decades ago. Chinese actors embrace experimentation and avoid easy certainties because it worked for them in the past—“if you want to get rich, build a road first” is a popular Chinese saying. Chinese actors are also comfortable with opaque deals because such deals have not prevented them from lifting millions out of poverty. As the China Eximbank president said, “if the water is too clear, you don't catch any fish” (Brautigam, 2009, p. 296). However, this “Beijing consensus” is at odds with contemporaneous Western norms, the so-called “Washington consensus” (Collier, 2007). In the Washington consensus, foreign aid is conditional on the recipient of funds satisfying multiple political and economic conditions. The value of this conditionality is also being challenged (Jepma, 1991; Sachs, 2006).

Our study suggests that both approaches to structure capital-intensive developments are arguably trying to do too much. Extant studies suggest that effective interventions in developing economies need to “work with the grain” and see “things as they are and to work from there” (Levy, 2014, p. 209). An extreme overlapped approach may be well-intended, but seems oblivious to local laws that govern property rights and set organizational boundaries. This approach seems to be premised on the possibility of changing, during implementation, the economic and sociopolitical fabric and replacing it with new “traits” (Hirchman, 1967). But the developments then become wagers. Given the costs that this predicament accrues in terms of opaqueness, adaptation, and risk of failure, it is reasonable to ask if it is worth it.

The socio-economic conditionality that is a prerequisite to start the implementation stage under a sequential approach has two merits. First, it creates a structure that allows for more transparency in buyer-supplier relationships because there is more common knowledge about the transaction before entering into a formal agreement. And second, less uncertainty improves the reliability of implementation and reduces adaptation costs. The problem is that in an environment of multiple “lacks,” it is difficult to meet all the conditionality needed to move into implementation. Hence, what a sequential approach achieves pales in comparison to what it pledges. This suggests that a sequential approach cannot ward off a less conspicuous failure—the missed opportunities—for which no one seems accountable for.

To choose between an extreme overlapped approach and a sequential approach is, therefore, a choice between a rock and hard place. One possibility worth exploring is the effectiveness of hybrid development structures between the two extremes. Allowing for experimentation toward hybrid structures requires institutional changes for the funders, without trying to alienate anyone. This point is important, considering both China and Western agencies are equally important infrastructure financiers in developing countries (Foster et al., 2009). Furthermore, if we accept the premise that eliminating key system bottlenecks requires consensus, we want to explore ways to speed up consensus building irrespective of the development structure. One avenue worth exploring is the impact of opening up the boundaries of the project organization to local intermediaries with deep know-how of the nuanced local circumstances. Nongovernmental and nonprofit actors may be able to mediate cooperation between traditional project participants, and help them engender solutions for difficult trade-offs. Local intermediaries may also be able to work around institutional voids in ways traditional participants cannot because they either lack the know-how or are shackled by their rules—an idea successfully tried to speed up health infrastructure development in settings of poverty (Dutt, Hawn, Vidal, Chatterji, McGahan, & Mitchell, 2016; McGahan, 2015).

Conclusion

In this study, we sought to advance our understanding of the structure-performance relationship in capital-intensive developments of complex sociotechnical systems. We respond to calls for using developing economies, the last research frontier in management studies, as a context (George, Corbishley, Khayesi, Haas, & Tihanyi, 2016; Kiamerhr, Hobday, & Kermanshah, 2013; Klingebiel & Stadler, 2015). Using urgent infrastructure projects in developing economies as a context, we start by tracing slippages in performance targets to pluralistic organizational structures. We also reveal how scarcity of slack and a lack of umpires exacerbates difficulties in forging consensus and amplifies performance slippages. We then identify two approaches to structure the development process, neither of which is unarguably superior. These insights have important implications to policy and literature.

The debate over the structure-performance relationship in development projects of complex systems has been stuck between two competing arguments: One sees advantages in the overlapped approach to speed things up under conditions of uncertainty. The other advises against it because of high adaptation costs and a deficit in accountability. Our study suggests that a better framing is to see the two approaches as two ends of a spectrum of alternatives that people can choose as a function of the resources available to them and the environmental constraints they face at the time of choosing. This is an analytical choice, though. Our study reveals situations where only one choice is in the cards, and it can be unfair to critique people on the presumption that the environment gives them a choice.

Our research has limitations, of course. By sampling cases from different countries and involving different funders, we show that slippages in performance occur, irrespective of the context and the structure of the development process. However, a unifying characteristic of our sample is a system of property rights in the environment. It remains indeterminate how the lack of this condition would change our insights. Our sample is also limited to what Hirchman (1967) calls “nonsite bound” or “footloose” developments. These schemes are vulnerable to political interference because the promoter is not invested with the authority that comes with developing a nonsubstitutable resource. Hence, disputants tend to disarm late, and once they give up, their fight can be taken up by others. The lack of technological complexity and unmovable deadlines—two characteristics of the projects in our sample—further amplify their vulnerability to political interference. Complicating matters was the existence of alternatives to the services that the sampled projects aimed to provide; as Keynes (1930) put it, “chances for action struggle to take off if there are alternatives (moderate evils) for intolerably bad options” (p. 175). It is reasonable to presume that not all capital-intensive developments are as vulnerable to political interference as the focal ones.

Further research is also merited regarding the extent to which the choice between alternative ways to structure the development processes extends to advanced economies. In advanced economies, “extreme” (Pettigrew, 1973) pluralism makes it hard for a dominant coalition to gain sufficient power to impose its preferences on others. This condition makes it unlikely that an extreme overlapped approach can extend to advanced economies. But the choice of how far to overlap the two stages is still relevant: Cooperation between promoter and development partners dampens uncertainty in implementation, but increases the risk of impasse if cooperation fails to flourish—there is no free lunch. We cannot also assume that disputants will foresee all the potentially contentious issues without accessing the suppliers’ know-how. But they will struggle to access that know-how unless they overlap, to a degree, planning and implementation. Furthermore, some issues may be unforeseeable before starting implementation. Investigating how much difference it makes delaying the point at which planning and implementation overlap in advanced economies merits further research.

Let us conclude by arguing that the structure of the development process is not the determinant to speed up a capital-intensive development or to improve the reliability of the performance targets. These one-off developments represent opportunities of value creation and appropriation for multiple autonomous actors with conflicting subgoals. We want to accept that, under pluralism, what gets done in the end, what it costs, and the time it takes, is all conditioned by what is politically possible, given the resources that are available.

References

Alexander, C. (1964). Notes on the synthesis of the form. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Baldwin, C. Y. (2008). Where do transactions come from? Modularity, transactions, and the boundaries of firms. Industrial and Corporate Change, 17(1), 155–195.

Baldwin, C. Y. (2015). Bottlenecks, modules and dynamic architectural capabilities. Harvard Business School, Working Paper Series, 15-028.

Baldwin, C. Y., & Clark, K. B. (2000). Design rules: The power of modularity (Vol. I). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Bertalanffy, L. (1968). General systems theory: Foundations, development, applications. New York, NY: George Braziller.

Biernacki, P., & Waldorf, D. (1981). Snowball sampling: Problems and techniques of chain referral sampling. Sociological Methods & Research, 10, 141–163.

Brautigam, D. (2011). The dragon's gift: The real story of China in Africa. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Brooks, J. F. P. (1975). The mythical man-month. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Clark, K. B., & Fujimoto, T. (1991). Product development performance. Strategy, organization and management in the world auto industry. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Cleland, D. I. (1986). Project stakeholder management. Project Management Journal, 17(4) 36–44.

Cleland, D. I., & King, W. R. (1968). Systems analysis and project management. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Collier, P. (2007). The bottom billion: Why the poorest countries are failing and what can be done about it. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Cooper, R. (1990). Stage-gate systems: A new tool for managing new products. Business Horizons, 33(3), 44–55.

Cyert, M. D., & March, J. G. (1963). A behavioral theory of the firm. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Davies, A., & Brady, T. (2000). Organisational capabilities and learning in complex product systems: Towards repeatable solutions. Research Policy, 29(7–8), 931–953.

Denis, J.-L., Dompierre, G., Langley, A., & Rouleau, L. (2011). Escalating indecision: Between reification and strategic ambiguity. Organization Science, 22(1), 225–244.

Denis, J.-L., Lamothe, L., & Langley, A. (2001). The dynamics of collective leadership and strategic change in pluralistic organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 44(4), 809–837.

Dutt, N., Hawn, O., Vidal, E., Chatterji, A., McGahan, A., & Mitchell, W. (2015). How open system intermediaries address institutional failures: The case of business incubators in emerging-market countries. Academy Management Journal, 59(3), 818–840.

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532–550.

Eisenhardt, K. M., & Tabrizi, B. N. (1995). Accelerating adaptive processes: Product innovation in the global computer industry. Administrative Science Quarterly, 40(1), 84–110.

Flyvbjerg, B., Bruzelius, N., & Rothengatter, W. (2003). Megaprojects and risk: An anatomy of ambition. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Foster, V., Butterfield, W., Chen, C., & Pushak, N. (2009). Building bridges. China's growing role as infrastructure financier for Sub-Saharan Africa. Public-private Infrastructure Advisory Facility. Trends and Policy Options. No. 5. The World Bank, Washington D.C.

George, G., Corbishley, C., Khayesi, J. N. O., Haas, M. R., & Tihanyi, L. (2016). Bringing Africa in: Promising directions for management research. Academy of Management Journal, 59(2), 377–393.

Gibbons, R., & Henderson, R. (2012). Relational contracts and organizational capabilities. Organization Science, 23(5), 1350–1364.

Gil, N. (2007). On the value of project safeguards: Embedding real options in complex products and systems. Research Policy, 36(7), 980–999.

Gil, N., & Baldwin, C. (2013). Sharing design rights: A common approach for developing infrastructure. Harvard Business School Working Paper, 14-025.

Gil, N., & Tether, B. (2011). Project risk management and design flexibility: Analyzing a case and conditions of complementarity. Research Policy, 40(3), 415–428.

Gil, N., Tommelein, I. D., & Schruben, L. W. (2006). External change in large engineering design projects: The role of the client. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 53(3), 426–439.

Hall, P. (1972). Great planning disasters. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Hirchman, A. O. (1967). Development projects observed. Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institution.

Hobday, M. (1998). Product complexity, innovation and industrial organisation. Research Policy, 26(6), 689–710.

Hobday, M. (2000). The project-based organization: An ideal form for managing complex products and systems? Research Policy, 29(7–8), 871–893.

Hughes, T. P. (1987). The evolution of large technological systems. In W. Bijker, T. P. Hughes, & T. Pinch (Eds.), The social construction of technological systems (pp. 51–82). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Iansiti, M. (1995, Fall). Shooting the rapids: Managing product development in turbulent environments. California Management Review, 38(1), 37–58.

Jarzabkowski, P., & Fenton, E. (2006). Strategizing and organizing in pluralist contexts. Long Range Planning, 39(6), 631–648.

Jepma, C. J. (1991). The tying of aid. Paris, France: OECD Development Centre Studies.

Jessop, B. (1997). The governance of complexity and the complexity of governance. In A. Amin & J. Hausner (Eds.), Beyond market and hierarchy (pp. 95–128). Cheltenham, England: Edward Elgar.

Jick, T. D. (1979). Mixing qualitative and quantitative methods: Triangulation in action. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24(4), 602–611.

Ketokivi, M., & Mantere, S. (2010). Two strategies for inductive reasoning in organizational research. Academy of Management Review, 35(2), 315–333.

Keynes, J. M. (1930). A treatise on money. London, England: Macmillan.

Khanna, T., & Palepu, K. G. (2010). Winning in emerging markets: A road map for strategy and execution. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press.

Kiamehr, M., Hobday, M., & Kermanshah, A. (2013). Latecomer systems integration capability in complex capital goods: The case of Iran's electricity generation systems. Industrial and Corporate Change, 1–28.

Klingebiel, R., & Stadler, C. (2015). Opportunities and challenges for empirical strategy research in Africa. Africa Journal of Management, 1(2) 194–200.

Langley, A. (1999). Strategies for theorizing from process data. Academy of Management Review, 24(4), 691–710.

Lenfle, S., & Loch, C. H. (2010). Lost roots: How project management came to emphasize control over flexibility and novelty. California Management Review, 53(1), 32–55.

Levy, B. (2011, October). Can islands of effectiveness thrive in difficult governance settings? The political economy of local-level collaborative governance. Policy Research Working Paper 5842. The World Bank, Public Sector Governance Unit.

Levy, B. (2014). Working with the grains: Intergrating governance and growth in development strategies. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). But is it rigorous? Trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation. In D. D. Williams (Ed.), Naturalistic evaluation (pp. 73–84). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Lundrigan, C., Gil, N., & Puranam, P. (2015). The (under) performance of megaprojects: A meta-organizational approach. Proceedings of the 75th Academy of Management Conference.

McGahan, A. (2015). The power of coordinated action: Short-term organizations with long-term impact. Rotman Magazine, 7–11.

Merrow, E. W., McDonwell, L. M., & Arguden, R. Y. (1988). Understanding the outcome of megaprojects. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1984). Qualitative data analysis: A sourcebook of new methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Miller, R., Hobday, M., Lewroux-Demer, T., & Olleros, X. (1995). Innovation in complex systems industries: The case of flight simulation. Industrial and Corporate Change, 4(2), 363–400.

Miller, R., & Lessard, D. (2001). Strategic management of large engineering projects: Shaping institutions, risks and governance. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Morris, P. W. (1994). The management of projects. London, England: Thomas Telford.

Morris, P. W., & Hough, G. H. (1987). The anatomy of major projects: A study of the reality of project management. Chichester, England: Wiley.

Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions of collective action. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Ostrom, E. (2005). Understanding institutional diversity. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Ostrom, E., Gardner, R., & Walker, J. (1994). Rules, games, and common-pool resource problems. In Rules, games, and common-pool resources (pp. 3–21). Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Press.

Pettigrew, A. M. (1973). The politics of organizational decision making. Abingdon, England: Taylor & Francis.