Chapter 15

Serious Learning Games: Where Rules Rule

As instructional designers, one of the things we should fear most is creating boring instruction that learners seek to avoid or escape however they can. The very idea of a game seems attractive and energizing, as people engage in games voluntarily—quite the opposite of how they react to another dreary classroom training class or dreadful e-learning course. But games can also consume a lot of the learner's time. And there's the question, Can they really accomplish serious instructional goals?

As with all great creative achievements, it looks to the many designers that one must be born with unusual talents to create successful games or work tirelessly for thousands of hours. When it comes to games, we understand that markets allow corporations to spend extravagant sums to build commercial games just for their entertainment value. They start with multimillion dollar budgets, then search out top talent, outfit them with the latest and most powerful hardware and software tools, and set them to work in very un-corporate-like environments. And still they expect only a few of these efforts to achieve great success.

How then can we even contemplate creating instructional games with essentially no time to develop our game design skills and relatively minuscule budgets?

This chapter reveals the fundamental components of successful games, showing that a game need not be complex or expensive to exhibit strong appeal to players. It notes that nearly all games depend on players learning and that commercial games have surprisingly much in common with e-learning. We set the stage for later chapters in which we see how to integrate instructional content and entertaining games to create effective serious learning games.

Fun and Learning

Learning is often associated with drudgery—a focused effort that isn't pleasant, that isn't playtime. Homework conjures up hours of drudgery and sacrificing time that could be spent with friends, fun, or needed relaxation. When we hear students talk about having to study, many of us recall those nagging obligations. We're relieved we've been there, done that, and no longer have it hanging over our heads. All that work when we would have preferred to be playing and having fun.

Generations have inherited the notion that, if it's fun and something we would do voluntarily, it can't be learning. Learning is a serious thing. It's work and isn't meant to be fun. The implication is that the distinguishing factor between learning and play is that, while play is easy and fun, learning isn't either of these things. And, of course, we've probably all witnessed instructors trying to make learning fun. And it wasn't.

But wait. We expect to expend energy when we play games and sports. And those activities are fun by definition. We participate in them voluntarily and precisely because they're fun. We can be delighted when we've exhausted ourselves and played well. We're doubly delighted if we've won or at least improved over past performances.

Hold on. That sounds like fun and effort are natural ingredients for both play and learning. Why not consider them prerequisites? Just as with games, we should expect to expend energy and have fun learning!

Let's Play! (And See What We Can Learn!)

There's an interesting dissonance here that mustn't be ignored. People, including some of those funding training development, tend to think fun activities aren't particularly valuable (except for relief, maybe). And they think strenuous activities will be rejected by trainees who would be having anything but fun. This line of thinking can lead to unfortunately “easy” e-learning that is dry and, well, boring.

Learning games present great relief from boring e-learning and offer an excellent learning platform, producing significant performance enhancement. We need to get leaders on board with just how smart it is to up the ante for investment in fun Serious Learning Games (SLGs).

It's Not Rocket Science

The ideas that learning can be a game and a game can provide valuable learning aren't hard to grasp, but they may not be everyone's first thought. In support of the hampering perspective of fun versus learning (pick one) are bushels of attempts to make learning fun that resulted in boring games that produce little learning—failures on both scorecards. It would seem a simple and natural concept (fun games + learning activities = fun learning), but the combination has often resulted in anything but fun or learning.

Although learning is integral to games, it nevertheless seems to be quite challenging to inject instructional events into games without annihilating the fun. Is it because as players we sense seriousness when the content appears instructional and therefore take on a recalcitrant attitude? Does content need to be frivolous for us to keep our sporting hats on? Can we have fun only if it's something we don't have to do?

My Stance

Making e-Learning Worse

I have no reservation about promoting e-learning in general. It has many, many capabilities to assist each learner reach competency. Next to a private mentor, whom I'd often (but not always) prefer, e-learning offers great benefits—when it's done right, of course. Not all e-learning is alike. And when e-learning is bad, it's really bad. Even mediocre e-learning is bad.

Make no mistake about it; doing e-learning right isn't as easy as throwing some presentation content together, even if you can present it with crisp clarity and professional-quality media. Although advancing tools help us tremendously to kick out digital courseware, it still takes thought, time, and effort to create e-learning that's worth the learner's time. And, if after that, the e-learning experience isn't fun, I feel we've still missed the mark. We should always create learning experiences that are engaging, valuable, spirited, and, well, fun!

There are many ways to give learning experiences the appeal of games. So many, in fact, that some scholars are grappling to identify and catalog them (Breuer and Bente, 2010). Karl Kapp (2014) is tremendously insightful and helpful in his book on gamification and his fun conference presentations. But as all working studiously in this field note, not all games have equal appeal. And when learning games are bad, they're really bad. Even mediocre learning games are usually worse than straightforward tutorials.

So, how can we get it right?

The Essence of Serious Learning Games

As always, my intent is to drive immediately to practical, applicable principles and guidelines. You will have no trouble finding guidelines for game design, even for learning game design elsewhere. A quick Internet search will return hundreds of links ready to send you on your way. But my assessment is that many of these enthusiastic mentors, while speaking eloquently on the subject, will mislead you or miss the critical points, even while their points seem logical and drawn from experience. Many of these sources oversimplify the issues, whereas some make the topic more complicated than it really is.

Some sources, for example, confuse gamification with SLGs. They may talk about the importance of scoring, power-ups, sound effects, great graphics, high-energy animations, and so on, because those elements are common in games. But while their novelty can be amusing and entertaining, you can create great games, learning and otherwise, without them. And, conversely, you can have all the bells and whistles without having created an effective learning game, serious or otherwise.

As noted, Breuer and Bente have undertaken an effort to categorize games with particular focus on SLGs and how they relate to other educational concepts. These researchers observed there are “many partially conflicting definitions of serious games and their use for learning purposes.” The numerous efforts cited to classify games reflect the complexity of the issue. Indeed, games have many attributes, which, when added to the number of attributes each instructional paradigm has, result in an unwieldy list.

For the pragmatist, it's important not to get hung up on terminology, but rather to focus on the critical attributes of SLGs and to gain confidence that proper deployment of them will make our learning experiences effective. Ornamentation can refine our work, but with much tighter constraints on learning game development than on developing mass-market games for entertainment purposes only, we need to skillfully address critical elements first.

The Fundamentals

What Makes a Good Game?

I've learned you can create great games, instructional or not, without animation, sound effects, and all the typical ornamentation of video games, some of which is very expensive. I learned this from an outstanding keynote presentation given by Eric Zimmerman in 2009 at an e-Learning Guild's DevLearn conference. Eric (here's his website: ericzimmerman.com) asked the audience, “What makes a good game?”

| We answered… | Eric replied… |

| Great graphics? | Nice to have, but no. Not essential. |

| Cool animation? | Nice to have, but no. Not essential. |

| Sound effects? | Nice to have, but no. Not essential. |

| Timer? | Nice to have, but no. Not essential. |

| Story? | Nice to have, but no. Not essential. |

| Scoring? | Nice to have, but no. Not essential. |

| Levels? | Nice to have, but no. Not essential. |

| Leaderboard? | Nice to have, but no. Not essential. |

Failing to provide a satisfactory answer over an extended period of time, we finally gave up. I think it's pretty interesting that the hundreds of us in the auditorium couldn't find the answer Eric was looking for. He finally revealed his insight: “What makes a good game? Good rules.”

“Good Rules–Good Game.”

Zimmerman's repeated answers of, “Nice to have, but not essential to a good game,” are something I've thought about many times as I've pondered why it seems so hard to develop instructional games that have the fun and attractiveness of successful entertainment games. I've come to understand and greatly appreciate his point: “good rules–good game; poor rules–poor game.” He's right. And his insight is particularly important to those of us interested in merging games and instruction. You can have good games without expensive ornaments and enhancements, but you can't have a good game that doesn't have good rules.

Consider tic-tac-toe as an example (as Eric did). Tic-tac-toe is a classic and enduring game based on a simple nine-cell grid. A paper napkin and a pencil are sufficient components (as all parents caught with restless children at slow restaurants know). No graphics, animation, sound effects, story, scoring, levels, or leaderboard required. What more do you need than a napkin and pencil? The rules. Players need to have rules to govern their play and determine who wins and under what circumstances.

Rules and Strategies as Content for Learning

Rules provide a critical element of context for game play while strategies provide the means to winning. Rules and strategies are foundational to the structure and nature of a game. Both rules and strategies have to be learned, of course, so game designers and instructional designers share a common interest in learning. Instructional designers have the additional need for learned skills to be transferable to useful performance outside the game.

Because games succeed based on how much fun they are to play, game designers have a keen interest in making it quick and easy to get started. The learning necessary to play should not be a distraction to the fun of playing. As instructional designers, we should share this interest with game designers, although we have a complementary interest in making sure the fun isn't a distraction to the learning. But game designers are often more adept than we are at keeping learners learning and practicing over extended periods of time, even to the point of overlearning and developing robust skills. We need to understand and apply their techniques.

Types of Rules

For understanding games more deeply and using them for instructional purposes, it is useful to divide game rules into two groups, Rules of Play and Outcome Rules. These rules define how a game works:

| Type of Rule | Definition |

| Rules of Play | What players must, can, and cannot do |

| Outcome Rules | How the game responds to player actions |

Such stipulations can be written as production rules, that is, as specific if-then statements, and often are in game design and development, especially in programming. Here are some examples from tic-tac-toe:

| Type of Rule | Example Tic-Tac-Toe Rules1 |

| (shown in production rule syntax) | |

| Rules of Play | If it's Player 1's turn, then Player 1 must place one and only one X marker in an empty cell. |

| If it's Player 2's turn, then Player 2 must place one and only one O marker in an empty cell. | |

| Outcome Rules | If Player 1 has just placed a marker, it becomes Player 2's turn. |

| If Player 2 has just placed a marker, it becomes Player 1's turn. | |

| If a Player has placed three markers in a row (horizontally, vertically, or diagonally), then that player wins, and the game is over. |

1These are rules for contemporary play. There have been many variations, such as those that allow players only three markers, but markers can be moved from one cell to another as a turn of play.

To play a game, it's sufficient to learn the Rules of Play and Outcome Rules. But players must learn more to be successful (unless the opponent is clueless). The successful player learns strategies—when and how to take specific actions—and applies them effectively. This is where we see the primary opportunity to use games for serious instructional purposes.

Strategies are actions taken based on learning, recognition, recall, and reasoning. Even if these mental processes don't reveal a strong basis for an action decision, they can narrow the choices from which to make an “educated” guess. Developing successful strategies requires learning both types of rules (Rules of Play and Outcome Rules). Strategies are useful, of course, only in games that give players options and a basis for choosing among those options. Therefore, an important criterion for choosing a game structure for an SLG is the extent to which it gives players options and relevant criteria for choosing among them.

Merging targeted performance outcomes into the game rules themselves separates SLGs from the generally less effective, less serious, but still valuable and easier to create gamification, as we'll see in a later discussion. But for SLGs, the parallel between successful player strategies and successful job performance is a key concept.

Anatomy of a Game of Strategy

Again I'll use tic-tac-toe as an example of rules and strategies. I hasten to point out that the content and strategies of tic-tac-toe are not very transferable to performance abilities outside the game, but we'll get to that essential element in the next chapter.

Rules of Tic-Tac-Toe

Rules of Play: What must, can, and cannot be done

- Players must alternate turns.

- Each player must use a unique set of markers (commonly Xs and Os).

- Each player must add one and only one marker per turn.

- A marker may not be placed in an occupied cell.

- Once placed, markers cannot be moved.

Outcome Rules: The Games Response to Player Actions

- 6. The game ends if all cells are occupied.

- 7. A player wins and the game ends if he or she has three markers in a row, whether vertically, horizontally, or diagonally.

Strategies of Tic-Tac-Toe

- If it's the first play, then (as production rules) the player should take a corner cell, as the second player will then have the fewest winning options.

- If the first player initially takes a corner cell and the second player does not take the center, then the first player can win by next choosing another corner (leading to two incomplete rows, only one of which the second player can block).

- If the first player takes a corner cell, then the second player should take the center square to avoid losing per consequence number 2 (assuming the first player plays strategically).

- If one player has two markers in a row, then the other player should fill the third cell in the row to block (or risk a likely loss).

The Rules of Play need to be learned first and then the strategies can be learned. It's essential to know what options you have as a player—what you can and cannot do—before you can begin to understand how strategies work, let alone discover valuable strategies yourself. With multilevel games, players learn a basic set of rules and then learn how to apply them successfully. Successes at the first level reveal additional rules associated with newly activated options, which enable additional strategies. Learning advances by alternatively learning rules and then mastering strategies.

Making a Serious Learning Game

Understanding the essential role rules play in games provides the basis for SLGs. As we either develop an entirely new game or adapt an existing one to use instructionally, rules and strategies that build on the rules are a prime design focus. As we'll explore in much more depth in the next chapter, instructional content can usually, if not always, be written in the form of rules. Examples:

- If the product being returned was purchased within the last 60 days, then offer the choice of a cash refund, product replacement, or store credit.

- If the light switch works sometimes but not always, then check to see whether other switches are on the same circuit and exhibit the same behavior.

- If writing for publication, then make sure you schedule time to set aside your first draft for several days before making a second pass.

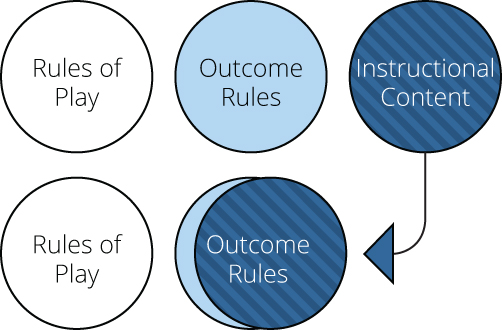

Once instructional content is formatted in this way, the design objective is to see how fully the content can become the game's Outcome Rules. Ideally, all instructional content rules would overlap on the Outcome Rules and/or the Rules of Play. See Figure 15.1

Figure 15.1 SLGs merge instructional content and Outcome Rules.

The Takeaways

Games require players to learn something even if it's only the Rules of Play. And learn we do in the fun spirit of playing games. Games prove that learning can be fun and that we need not think learning must be an arduous task to be undertaken only when forced. Many past attempts to combine games and learning have not recognized the fundamental requirements of each, resulting in boring games that are neither fun nor instructional.

Developing successful learning games requires understanding what's essential to a successful game. A primary concept is that good games are founded on good rules. If the rules are poor, no amount of ornamentation will sustain interest and involvement for long.

There are two types of game rules: Rules of Play and Outcome Rules. Both types can be written as production rules (i.e., in an if/then format) and have to be learned to be a successful game player. A third type of rule, Game Strategies, must also be learned to be successful in most games, even in tic-tac-toe. SLGs are made by making the content to be learned and game rules the same—at least to a large extent.

Instructional content can be written as production rules also, which facilitates integrating instructional content and game structures.