E-LEARNING:

A POSITIVE SKEPTIC'S JOURNEY INTO NIGHT?

Martyn Sloman

I have daily angst regarding e-learning. What we do in education and training is important. Performance abilities can have profound effects on individual lives as well as the organizations to which they belong. But are we really helping people all that we can, or are we short-changing them? Author Martyn Sloman states bluntly, “Progress to date on implementing e-learning has not reflected well on practitioners; the debate has been about technology rather than learning.” Martyn feels we have not capitalized on the potential and that our failure is due in large part to misplaced focus. He draws on research and experience at the UK Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development to identify a set of key principles for effective e-learning and also considers the new challenges posed by Web 2.0 Social Networking. I appreciate his critically important commentary.

The title of this personal reflection on e-learning is taken from the name of a play by Eugene O'Neill, the great American playwright. To quote from Wikipedia, nearly all O'Neill’s plays involve some degree of tragedy and pessimism; the characters in A Long Day's Journey into Night “constantly conceal, blame, resent, regret, accuse, and deny in an escalating cycle of conflict with occasional desperate and half-sincere attempts at affection, encouragement, and consolation.”

After more than a decade of monitoring and recording the progress of e-learning from a European vantage point, I have frequently felt irritated and frustrated at the misunderstanding of fundamental principles and the associated hype or over-selling. In this article I will try, by outlining progress and offering illustrations, to explain why I think this has happened and what we need to do if we are to move forward on a sounder basis. I remain convinced of the enormous potential of e-learning and, despite the opening paragraph, describe myself as a positive skeptic.

AN OBJECTIVE ASSESSMENT

The term e-learning first emerged in the fall of 1999 (Overton, 2009). There followed a period of great optimism. At the height of that period the management guru and author of In Search of Excellence, Tom Peters, addressed the Conference of the American Society for Training and Development (ASTD) in Florida in June 2002. Urging his audience to progress more rapidly, he argued that the goal should be that 90 percent of training in organizations should be delivered electronically by 2003.

In fact e-learning certainly has not, and will never, amount to 90 percent of training in organizations, however the term is defined. What we have witnessed is a gradual and probably irreversible growth in “learning that is delivered, enabled, or mediated using electronic technology for the explicit purpose of training in organizations,” to draw on the definition advocated by the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD, 2008a).

Between 2001 and 2008 I worked as a full-time researcher at the CIPD, the 130,000-member-strong UK professional association for those involved in personnel management and development. During this period we monitored the progress of e-learning through surveys, case studies, and forums. Together with ASTD we produced a useful body of information and some reliable statistics.

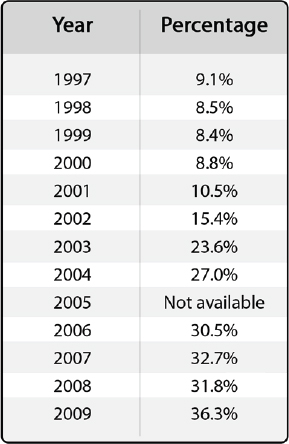

Each year in its State of the Industry survey, ASTD reports on the percentage of training delivered through learning technology. Their reporting began in 1997 with under 10 percent. The percentage then plateaued, then noted steady growth to just over 36 percent for 2009 (the latest available at the time of writing) (ASTD, 2010). This progression is reproduced as Table 1 below.

Table 1. ASTD State of the Industry Reports on Percent of Learning Technology Used in Organizations, Primarily in the United States (Figure 15, p. 16)

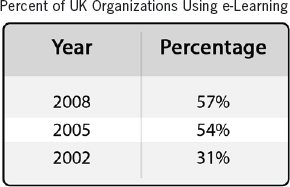

Similarly, the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development conducts an annual survey of their (mainly UK) members to monitor and chart progress of training and learning in the workplace. Every third year (most recently in 2008), an extended section on e-learning is included. The 2008 survey results offer a comparison with the 2005 and 2002 figures and the opportunity to reflect on progress and make some more general observations on technology in the workplace.

The news is mixed. There has been steady progress and good practice can now be identified, illustrated in Tables 2 and 3. The 2008 survey shows that more than half of the respondents (57 percent) reported that they are using e-learning (CIPD, 2008b). Moreover, of those who were not using e-learning, more than one quarter (27 percent) planned to do so in the next year. This proved beyond any doubt that e-learning has arrived. It is firmly established as a key part of training delivery. No questions were asked in the survey on the type of e-learning that respondents are implementing in their organizations. However, we acquired a good base of knowledge that suggested that the predominant form of e-learning is a web-based module format, normally produced for the organization concerned. Customized or bespoke e-learning applications have become predominant.

Table 2. CIPD Annual Learning and Development Survey: Percent of Organizations Using e-Learning, Primarily in the UK

It is important to note that the percentages reproduced in Tables 1 and 2 are not in any sense comparable. The U.S. data relates to the percentage of learning hours available through technology. The UK data relates to the proportion of organizations that are making e-learning available to their workforce. There is no established data available on the UK percentage of learning hours delivered through technology. However, less formal indications uncovered in the course of CIPD research have suggested that progress in the UK has not been as dramatic as in the United States. For example, using returned data from the 2008 annual survey, CIPD researchers estimated learning hours delivered through technology to be 12 percent, compared with a U.S. figure of above 30 percent (CIPD, 2008a).

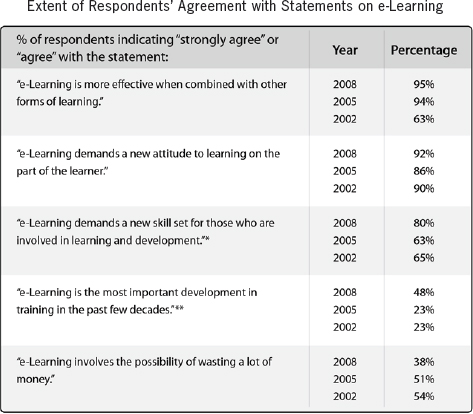

One other insight can be drawn from the CIPD surveys. In 2008, 2005, and 2002, respondents were presented with a series of statements on e-learning and asked whether they strongly agreed, agreed, neither agreed nor disagreed, disagreed, or strongly disagreed. Table 3 shows the extent of agreement for the five statements that appeared in all five surveys. It can be seen that two statements have emerged as representing shared wisdom on e-learning. The first, “e-Learning is more effective when combined with other forms of learning,” is the acceptance of the importance of what has become known as “blended” learning; the second, “e-Learning demands a new attitude to learning on the part of the learner,” emphasizes the need for a learner-centric approach to the subject. We need to act on as well as recognize this finding.

Table 3. CIPD Annual Learning and Development Survey

*In the 2005 and 2002 surveys, the statement used was “e-Learning demands an entirely new skill set for people involved in learning and development.”

**In the 2005 and 2002 surveys, the statement used was “e-Learning is the most important development in training in the past few decades.”

WHAT MUST WE LEARN?

So, after a shaky start, we have witnessed a gradual but inexorable rise in e-learning. However, such progress bears little relation to the wild optimism evident in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Actors in e-learning may not have “constantly concealed, blamed, resented, regretted, accused, and denied.” However, many of them have consistently oversold and overstated the advantages of e-learning; many more have ignored the need to proceed from an understanding of the basic principles that must underpin any intervention to promote training and learning in a corporate organization. Certainly, in the UK, government has behaved particularly badly as it has seized on e-learning as a cheap and easy way to encourage skills development (as one of the three illustrations below will demonstrate).

In the next section of this article, three short case cameos are presented. Taken together they provide the backcloth for an articulation of the basic principles that must govern any learning intervention.

Cameo 1. The first of the three cameos is hypothetical and is a direct quotation from a 2002 UK government publication (Transforming the Way We Learn, 2002).

“After assembly, the first period is GNVQ Science, in which digital learning materials on the school's intranet feature prominently. Currently, pupils are working through these in a three-week block. Uzman works independently on the unit on physical forces and regularly discusses his experiences with other pupils doing this through a virtual community of which he is a member. However, he knows that he can e-mail his science teacher to seek help with any assessment he has not understood. He also knows that, for this lesson, the teacher has prioritized direct support for another group of pupils who are having rather more difficulty with some of the ideas than he is.”

GNVQ is a UK vocational qualification and the assumption must be that Uzman is a sixteen-year-old school student.

Cameo 2. This cameo, which has the advantage of being true, is drawn from a family experience. My wife and I live in Norfolk, an agricultural part of the country, and she has a large extended family living nearby. One of her cousin's children was facing major problems at school. At the age of eleven he had difficulties reading and writing and his classroom behavior was unruly; the school was contemplating serious action. Matters were due to come to a head at the forthcoming parents' evening, when the teachers were due to give feedback to the mothers and fathers. To avoid what would be a very uncomfortable experience, the young man in question constructed a letter to the school, purporting to come from his parents. This stated that they would be unable to attend the parents' evening due to a death in family and went on to ask the school not to reply or contact them because they were so upset about the tragic occurrence. Not a bad achievement for someone with literacy problems!

Cameo 3. I know this cameo to be true but did not personally witness it. It concerns the introduction of e-learning through the distribution of CD-ROMs in a medium-sized UK supermarket chain. A PC was made available in each of the stores, relevant product dispatched, guidance material issued, and a telephone help-line established. An early call was received from an enthusiastic manager in a Midlands store who said: “We've hit a major problem. It says in the guidance you should look on the desktop. We didn't have any desks here, so we've put the computer on a table. What do we do now?”

LESSONS LEARNED—LEARNING VS. TRAINING

What should we take from these cameos? The Uzman cameo is hypothetical nonsense. It may be attractive, even inspiring nonsense, but it is nonsense nonetheless. Uzman is from a different planet from the teenage boys who attended a North London School with my two sons. Left to themselves with a PC and asked to work independently on the unit on physical forces, they would have done no such thing. They would have discussed the Arsenal score from the night before (and may well have accessed the site on the web). Getting them back into line would have demanded time from the teacher at the expense of the direct support for the other group of pupils.

The story of my wife's delinquent relative brings us to an important reality. It focuses on the distinction between ability and motivation and the importance of the latter in many situations. The boy was highly motivated by fear of consequences and produced a coherent letter (alas, in this case it was not coherent enough). This was something no one thought he had the ability to do and was not a skill he was willing to deploy in “normal” circumstances.

In our third cameo, the supermarket, the learners were motivated, but the interventions that were put in place simply did not take adequate account of their prior knowledge or starting-point.

Please note that all three cameos are about learning not training. This difference is absolutely fundamental. The 2004 CIPD Research Report “Helping People Learn” offered precise definitions of the terms training and learning: training was defined as “an instructor-led, content-based intervention, leading to desired changes in behavior” and learning as “a self-directed, work-based process, leading to increased adaptive capacity” (Reynolds, 2004). Training and learning are related, but conceptually different activities.

The critical point is that the same considerations apply to e-learning as to any other form of learning in the organization. Learning is a discretionary activity that takes place in the domain of the learner. Learning activities, of whatever form, will only receive managerial support if they are seen to add value to business and its customers or clients. They will only receive support from the learner if the learner is motivated and feels capable of undertaking them. Simply making content available on a personal computer and hoping that something will happen is not good enough. It has taken us far too long to grasp this essential truth. It forms the basis of a set of guidelines issues by the CIPD in a fact sheet and are listed below in Exhibit 1.

Exhibit 1. Implementing e-Learning—Key Lessons to Date

As e-learning has progressed, there has been a growing understanding of the steps that need to be taken to make it effective. Based on the experience gained over the last decade, the CIPD view is that the following principles should underline any strategy for e-learning.

- Start with the learner—Recognize the limitations of the population that you are trying to reach.

- Drive out resistance with relevance—If the e-learning material is seen as relating to something that matters in the organization, people are more likely to try to use it.

- Take account of intermediaries—Much learning requires an intermediary to advise and direct the learner. This is just as true of e-learning; it will not be successful if taken in isolation from other learning.

- Embed activity in the organization—This is a subtler point, but follows from the previous one. e-Learning modules should be seen as one element in an organizational learning strategy; where possible their use should be linked with instructor-led courses and other human resource management systems (for example, performance appraisal).

- Support and automate—This final catch-all point reinforces and underlines the others. e-Learning does not offer us the opportunity to automate all our learning processes. Instead, it is a powerful new element in a wider strategy, which requires support for learners in the context in which they learn.

GOING FORWARD IN DAYLIGHT

We have not made a good job of implementing e-learning for two reasons. First, we have been overly optimistic; we have allowed overstatement and hype to develop. Secondly, we have neglected basic learning principles and have been seduced by the technology. “Start with the learner—recognize the limitations of the population that you are trying to reach” rightly appears first on the list of principles set out above.

The most important challenge facing the training professional is to gain a better understanding of how people learn in his or her organization. Given that this is still true, we have not made a good job of the introduction of e-learning over the last decade. If we do not understand how people learn and impress our colleagues with that understanding, we are indeed likely to embark on a “long day's journey into night.” This has become particularly urgent with the emergence of what is now known as Web 2.0. It is essential that we do not repeat our mistakes now at a time of considerable new opportunity.

Over the last few years we have witnessed a series of interrelated factors that make collaborative learning using technology look like a more attractive option. Quite simply, people are likely to be more comfortable with this style of working. More people use a PC at work; broadband penetration is increasing—and it's a global phenomenon.

The second half of 2007 witnessed a huge increase in the use of the term “social networking.” The term is used imprecisely and often interchangeably with Web 2.0. At present there seems to be a clearer definition of Web 2.0 than of social networking. Web 2.0 is a term given to the second generation of Internet-based communities that encourage collaboration between users. A 2005 conference developed the idea that there were emerging changes in the way software developers and end-users were using the web as a platform:

“Web 2.0 is the business revolution in the computer industry caused by the move to the Internet as platform, and an attempt to understand the rules for success on that new platform.”

(From Wikipedia and attributed to Tim O'Reilly, a well-known U.S. writer and author)

For the advocates, there has been a sudden emergence of new opportunities for collaboration, co-creating and sharing of content, and enhanced communication. Wikis and blogs have entered the vocabulary of the learning and development manager. Certain activities, which can be included in social networking, have shown exponential growth. Among these are the networking sites like MySpace, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

A 2009 research report, “Web 2.0 and Human Resource Management” asks:

“Groundswell or Hype?” Working for the CIPD, Martin, Reddington, and Kneafsey offered the following working definition of Web 2.0 for HR professionals:

“Web 2.0 is different from the earlier Web 1.0, which focused on the one-way generation and publication of online content. Web 2.0 is a ‘read-write’ web providing a democratic architecture for participation, encouraging people to share ideas, promoting discussion and fostering a greater sense of community.” (emphasis in original)

(Martin, Reddington, & Kneafsey, 2009, p. 2)

Although the authors recognized the limited applications of Web 2.0 to HRM practice to date they identified the following as one of five ways in which Web 2.0 could add strategic value to organizations:

“Supporting employees using Web 2.0, such as wikis, employee discussion forums, and virtual reality sites, tools to help them to learn and share knowledge and experience.” (p. 32)

So does Web 2.0 mark a significant breakthrough in e-learning? Does it transform opportunities by creating a new environment in which the expert tacit information held within the firm could be widely shared, creating a powerful business advantage?

More sophisticated technology and more confident users certainly create new opportunities. However, these will not necessarily translate into activities that develop the knowledge and skills that deliver added value to a business and its customers or clients. Whether this welcome outcome occurs must depend on the nature of the business and the way it generates value through its people. Again, this is about learning, not about technology. Unfortunately, to date, the Web 2.0 vocabulary has developed from technology not from training or learning. “Blog,” for example, is an abbreviated form of weblog; “wiki” (a Hawaiian word meaning very quick) was coined to describe a type of computer software. These two terms and others are being used very imprecisely in a learning context as applications and understandings evolve.

There is a need to develop a better vocabulary if we are to grasp and address the implications for learning. This process must proceed by asking learners what mechanisms and practices they use themselves to acquire knowledge and skills. We can expect their answers to embrace less formal categorizations, for example, studying manuals, books, videos CD-ROMs or online materials; accessing information from the Internet; watching and listening to others at work; doing a job or similar work on a regular basis. This will take us in a learner-centred rather than a technology-centered vocabulary. Training and learning professionals must recapture the initiative from those who would promote technology for its own sake.

FINAL THOUGHTS

In some sense, little has changed since the arrival of e-learning in the late 1990s. Technology may have advanced and new potential opportunities created as a result. Learners may have become more sophisticated and confident in using the personal computers that are now on their desks. However, it is their preferences, attitudes, and motivation that must be understood if their learning is to deliver value to the organization. Our ten-year CIPD research program concluded that the best definition of the role of the trainer was: “supporting, accelerating, and directing learning interventions that meet organizational needs and are appropriate to the learner and the context.” This is as true of e-learning (whether Web 2.0 or previous applications of technology) as it is of the classroom.

REFERENCES

American Society for Training and Development. (2010). State of the industry report-2010, Alexandria, VA: ASTD. See www.astd.org.

CIPD. (2008a). CIPD fact sheet, e-learning: Progress and prospects. Accessible at www.cipd.co.uk/subjects/lrnanddev/elearning/elearnprog.htm.

CIPD. (2008b). CIPD annual survey report: Learning and development. www.cipd.co.uk/subjects/lrnanddev/general/_lrndvsrv08.htm?IsSrchRes=1

CIPD. (2008c). CIPD research insight: Supporting, accelerating, and directing learning: implications for trainers. www.cipd.co.uk/subjects/lrnanddev/general/_sadlrng.htm.

Martin, G., Reddington, M., Kneafsey, M.B. (2009). Web 2.0 and human resource management: ‘Groundswell’ or hype? London: CIPD.

Overton, L. (2009). 10 years on … the e-learning debate continues. Retrieved March 25, 2010 from www.towardsmaturity.org/article/2009/10/29/10-years-on-the-elearning-debate-continues/.

Reynolds, J., (2004). Helping people learn. London: CIPD.

Sloman, M. (2009). Learning and technology—What have we learned? Impact: Journal of Applied Research in Workplace e-Learning. Inaugural issue.