7

Structuring your loans

Summer holidays and jigsaw puzzles went hand in hand for me as a kid. They were an ever-present part of my holidays during my youth at my grandparents' holiday house. There was always a puzzle to work on somewhere on a table.

More so than other investments, property is like a really big jigsaw. It might be just one property, but the entire purchasing process can take an incredible amount of time to pull together.

So many different pieces need to fall into place for a property to end up in your possession. At a minimum, you need to traipse through dozens of properties searching for ‘the one'. At various stages, the buying process can go weeks with little happening. Then other people will chip in and help things along a little. You'll spend countless hours organising your finances, perhaps fail at auctions a few times, waste hours dealing with agents and lawyers. (And if this is for your home, you'll lose days packing, moving and unpacking.)

It doesn't just happen all at once. But right near the end, the pieces come together very quickly.

This chapter is about a very important piece of the property puzzle — structure. Sounds boring? Don't let that fool you. Structure is a crucial part of this whole property purchasing process. You can't just skip it and move on.

That attitude could, literally, cost you a fortune.

A poor structure can really bugger things up. When I talk about structure, I'm predominantly talking about two things — who owns the property and how the property is financed. The simplest errors, lack of thought, or ‘convenient' decision could cost you tens of thousands of dollars. That would almost defeat the purpose of making the investment in the first place.

Think I'm talking rubbish? Well, let me give you simple, but all too common, examples of costly structural mistakes.

The married couple that bought an investment property in joint names, when they were trying to start a family. One partner subsequently spent most of the next five to ten years either unemployed or in part-time employment, while having and raising their kids, while the other partner was consistently earning a salary of more than $100 000 a year.

Cost? Oh, probably tens of thousands of dollars … and counting. This was largely in missed tax deductions because the negative gearing was being claimed jointly against their incomes. Getting a tax deduction on a $0 income is worth, um, nothing. Every year until the property becomes positively geared is going to be expensive for them.

Or another couple who sold their home and wanted to park some cash for about nine months while they built their new residence. Unfortunately, they put the money in the redraw account of an investment property (not an offset account). They could no longer claim a tax deduction on the full loan, but only on the interest on approximately $30 000. It changed the financial viability of the property so much that they had to sell, incurring sales costs, and rebuy another investment property, incurring stamp duty.

Total cost: Around $25 000 in sale costs and stamp duties, not including the capital gains tax bill.

Or the three mates that bought a property together in partnership, who then struggled for years to exit the property at a profit and hold the friendship together. The structure of their loan had an impact on other financial decisions they wanted to make as individuals. (The bigger disaster would have been a destroyed friendship, but they managed to hold that together and come out with a small profit.)

It can get a whole lot worse than that. But it doesn't need to.

By making sure you have the right structures (ownership and loan) in place from the start, you can remove some (but not all) big risks that could otherwise derail or destroy your investment.

Make these decisions before you start looking and certainly before you get your loan (or pre-approval). While no amount of structuring can prepare perfectly for everything that might happen, there are certainly some situations that you should aim to avoid from the outset.

Stopping problems before they occur? Priceless.

Ownership — who's on the title?

Who's going to own it? If the ‘you' is a couple, the ownership options are: one person, the other person, or the couple jointly. Outside of individuals, other property owners can include partnerships, companies, trusts and self-managed super funds (SMSFs). Each is a different legal entity, which comes with differing asset bases, prospects and levels of protection.

If this property thing works out well for you, you'd want to protect the wealth it has created for you, wouldn't you?

The answer is an obvious yes. So, let's shine a light on the ways property can be owned and also, more importantly, how it shouldn't be owned, if asset protection is important to you. And in the second half of this chapter, I'll give you the crucially important section on structuring your loans to maximise your property interests.

Individuals

It seems so obvious, doesn't it? If it's just you, then you might not think you have an option except to buy it in your name. (You do, but I'll come back to that.)

If you're part of a couple, then there are three options: you, me and us.

Buying a property in individual names is the simplest way of doing it. There are no set-up costs and the documents required for borrowing are straightforward. For most individuals, this is the favoured and most cost-effective option.

But from an asset protection perspective, it leaves you (as an individual or a couple) the most vulnerable.

Why wouldn't you own it? There are many reasons, some of which many people don't think of until after it's too late. But the person who holds the property should usually be the person who is least likely to lose it.

‘Huh? What the …?'

Let me explain.

Many occupations run a higher-than-average chance of being sued for mistakes or errors (or plain bad luck) in their line of duty. These occupations include doctors, lawyers and accountants, but can include anyone who works with clients where personal or financial damage can be done. That means almost anyone running a small business. Truck drivers can have accidents, builders can make disastrous errors, restaurant kitchens could poison their customers … and the damages could run into the hundreds of thousands, even millions.

If one member of a couple is in the category that might get professionally sued, then would you want to protect the property from being lost if that could be avoided?

Let's take Mick and Jane. Jane is an obstetrician and Mick is employed at a bank. They bought the house in joint names. One of Jane's clients sues her over an error and wins millions. As an asset that Jane partly owns, the house must be sold to help pay the damages (she's later declared bankrupt).

However, had the property been bought in Mick's name only, it wouldn't be an asset that could be forced to be sold in this situation.

Similarly, small businesses can go broke. Too many do. If one member of a couple is running a small business — no matter how good they are at it — consideration should be given to having property assets in the name of the other partner (particularly if they are an employee in a low-risk industry). If you're both in positions that could be sued, then stronger consideration should be given to the likes of a family trust.

Buying with family and friends

With rising property prices, Australians are increasingly looking to co-invest with family and friends. Parents often want to help their kids get into property and offer to buy it with them. Friends who individually don't believe they could afford a property wish to join forces to get a foothold.

As a concept, joining forces and finances to buy property should certainly make it easier, shouldn't it? You can have your cake and …

Actually, hold that cake and don't eat it for a second. You might want it to throw at someone.

Me.

Yup, I'm about to make myself really unpopular to many of you. I've got plenty of tips and warnings in this book. And this is going to be one of the strongest. If you're considering buying property with others … DON'T DO IT!

Avoid going into property ownership with others, wherever possible. Property ownership is a complex and risky financial investment at the best of times. Adding another party will, often, double the potential risks involved, by adding big new dimensions to what could go wrong.

While done with the best of intentions, adding extra parties to the deal will dramatically reduce the chances that you'll be able to make a success of your property investment.

Why? Because you lose control in the following ways:

- You won't necessarily get to determine when you can sell the property. You may wish to hold it, but they want to sell it. Somebody has lost their job, is feeling under financial pressure, or just wants out. There's a divorce, a family bust-up, or just a general sense of panic.

- One party may wish to improve the property, while the other doesn't want to spend any money (or can't afford it at that time).

- One party thinks a particular real estate agent is doing a terrible job, but your partners disagree. You want to sack the agent, but you don't have the power.

They're the main, but by no means the only, potential problems.

Let me put it this way: You are tipping hundreds of thousands of dollars of your money into this investment — money that is either your own or that you're responsible for repaying to a bank.

Do you really want to have to seek agreement, or potentially negotiate, with someone else on whether you can or can't do something to protect this massive investment that you've made?

I've seen it turn ugly on too many occasions. Too much money gets blown on lawyers. Friends now won't speak to each other. Family functions get boycotted.

By no means are things guaranteed to get ugly. Far from it. But the risk of friction between owners when there is only one owner is zero. With multiple owners, it rises exponentially.

If you can avoid buying with others, do. This might mean buying a smaller place on your own, or something a little further out, or waiting until you've saved a bigger deposit, or until your income has increased.

If you can't afford to buy a property on your own, then should you really be buying a property?

However, if you intend to ignore that advice, and I know many will, then I wish you the best of luck and smooth sailing with your property partners.

There are ways of making it work. One way of taking out bickering about management issues is for one investor, preferably one with the most property-investment experience, to take majority ownership of the property, under a tenants-in-common ownership structure (more on this later in this chapter). This involves other investors taking minority shareholdings and effectively coming along for the ride on the investment. This still has its dangers, but at least management control will be understood from the start. Again, seek legal advice on the structure, because it has ramifications you need to understand.

If you do wish to proceed with a multi-person investment, here is a list to help reduce the risks involved.

- Make sure you have a proper written agreement covering who will be in charge of ongoing management decisions, how decisions will be made, when money will be spent.

- Have an exit strategy. Is there a generally agreed holding period? It should be in writing and with an indication, if not a hard date, of when the property will be sold.

- Cover what would occur if one person wants to sell, but another party doesn't. Can one buy the other out? How would a price be agreed?

- Determine the sinking fund to cover longer-term maintenance issues. How big does the buffer need to be and under what circumstances will the partners be obligated to tip money into it?

- Determine the emergency fund — how much and when would it be required from partners?

- Decide who is in charge of hiring and firing the agent and deciding on tenants.

- Decide how insurance issues will be handled.

- Decide how stalemates will be decided, or who will be consulted to settle any disputes (an external party you would trust to make an informed independent decision).

That is a start for discussions around a legal agreement that you should have before entering into any sort of shared arrangement. You should see a lawyer in regards to drawing up a property agreement.

Joint tenancy

Joint tenancy is where there is more than one owner and each owner shares an equal portion of the property; and the right of survivorship means that in the event of the death of one of the owners, the remaining owners receive the ownership of the deceased's property evenly.

If there are three owners of the property and one dies, the remaining two owners move from owning one-third each to one-half each.

This is the way that most couples own their home, if they own it jointly. When one partner dies, the living spouse inherits the entire property.

From a property investment perspective, joint tenancy works best for two individuals, or a couple, who have similar incomes (or are in the same marginal tax bracket) and are likely to remain that way.

Tenants-in-common

The other option for individuals to hold property is known as tenants-in-common (or TIC). Tenants-in-common are not required to hold equal portions (though they can) and, as a main distinction, can leave their ownership of the property in their wills to whoever they wish.

For example, you could have three owners, with one having 60 per cent of the ownership and the other two having 20 per cent of the ownership, or any mix, for any number of potential investors. In the example where there is a clear majority owner (greater than 50 per cent), the minority investors might be willing to accept that they have less, or no, say in the running of the property. Any shareholder agreement that they signed should probably reflect that the majority shareholder has management control of the property and the two minority shareholders, while able to voice their opinion on matters, are effectively coming along for the investment ride.

Where friends or family wish to purchase a property together, then using a tenants-in-common structure, where one person has majority control (even if it's 51–49 per cent) can reduce the potential for arguments over the management of the property.

A TIC owner can also sell their portion when they wish (though other buyers would likely be limited as they would have to deal with existing partners). This would usually mean potential purchasers are limited to one of the other TIC partners. That the ownership of the property can also be dealt with in the deceased's will can also mean that the other partners end up with a new partner they had not bargained on when they purchased the property.

TIC is often used by couples to hold property as 99 per cent in the higher-earning spouse's name and 1 per cent in the lower-earning spouse's name, then leaving the remainder to the other surviving spouse in the will. This allows the majority of the property to be tax-deductible for the higher-earning spouse.

Self-managed super funds (SMSFs)

It often seems like property ownership by SMSFs is the new kid on the block. It's not — SMSFs have always been able to own investment property. What is new is that SMSFs, since 2007, have been able to borrow to buy property. This has dramatically opened up the number of SMSFs that can buy property.

It is a highly complex way of holding investment property (if it is geared) and I discuss this in chapter 6. Anyone considering buying geared property in an SMSF is strongly advised to seek advice from a well-qualified financial adviser and/or SMSF-specialist lawyer.

Other significant property holding structures

While individuals and SMSFs are currently among the most popular ways to hold property, they are not the only ways. Other methods include trusts (discretionary, fixed and unit trusts), companies and partnerships. While each of these structures has some great qualities for property investors, specialist legal and financial advice before entering into these ownership structures is recommended.

- Trusts. Legal entities where trustees hold assets on behalf of beneficiaries, under the terms of a trust deed. Trusts can be complex legal entities and one of their main uses is for asset protection.

- Partnerships. Where two or more investors get together, usually for larger projects, to pool their capital and talent to buy, manage and (usually) sell property. A downside of partnerships can be, in some cases, unlimited liability for the partners and difficulty in exiting the partnership without it coming to a natural conclusion on sale of the property.

- Companies. Shareholders are the ultimate owners of companies and shareholders' liability is usually limited to the value of their shares. While companies can own property, they are usually the most expensive holding vehicle, because of regulatory requirements, which will usually require professionals to assist with set-up and ongoing management.

Structuring debt

The next part of the puzzle is how you best structure this monstrous — at minimum it's huge, but will be monstrous if you're building a portfolio — debt that will come with the property you're purchasing.

For some, the answer is simple. If you're buying your first property (home or investment) with a healthy deposit, the answers are generally going to be reasonably straightforward. That doesn't mean you can just slap this thing together, or that you should necessarily just take a bank's recommendation. (I assure you, they will have their own best interests at heart, not yours. Mortgage brokers at least have a degree of independence.)

And anyone who has aspirations of building a property portfolio needs to get things right from the start. Sometimes when you get things wrong, it simply can't be undone. Other times, it can be undone, but it can be very expensive (in money and/or time).

There is no perfect set-up that can be laid out in a book like this. That's because we're all different. There are many base scenarios, which I lay out in this chapter and elsewhere in this book, but you will inevitably need to tailor those solutions to your circumstances. If you can confidently put together the basics for yourself, great. If not, get a mortgage broker involved.

Your first home loan

As discussed in chapter 6, the best way to buy your first home is with a big deposit. Having a deposit of 20 to 25 per cent — depending on first-home buyer concessions and grants in your state — will mean that you won't have to pay lender's mortgage insurance (LMI — see later in this chapter).

If you borrow above 80 per cent, you'll likely have to pay LMI.

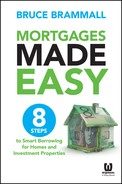

In figure 7.1, I show how best to set up your loans for a reasonably straightforward home loan.

Figure 7.1: setting up your offset account

In most cases, you will simply want one loan (with a redraw option), one offset account, possibly one credit card, and away you go (see table 4.3 on p. 60). If you want to have all of your loan as variable-rate (see chapter 4), have all of your income put in the one offset account and pay your mortgages from there. This set-up will be efficient, making the most of your offset account and potentially benefiting also from the credit card.

However, if you want to split your loan to have it part fixed and part variable, then you will end up with two loans. This will usually still come with one offset account, which will save you interest on the variable loan only (though banking products are evolving quickly). As displayed in figure 7.2, it will usually be most efficient (as in, save you the most money) to have all loans paid from the same offset account.

Figure 7.2: setting up your offset account for multiple loans

Technically, you can have any number of loans against the one property, though some banks will limit you to two, or will charge extra fees for extra splits. Having extra loans can be useful for a car loan, an investment loan, or line of credit, and many banks can accommodate this.

What if there's a chance I might turn my home into an investment?

If this is a possibility at some stage, then getting the structure right at the start is crucial to how successful the property will be as an investment, as well as how low the mortgage is on your next home. This could save you thousands of dollars, potentially each year after you turn it into an investment property.

I lay this out in detail in chapter 5. Essentially, if your home is going to be turned into an investment property, don't pay down the loan. Keep as much of your own money for the deposit on the next home. At the same time, you wish to keep the debt on the current home as high as possible to keep the maximum deductions you can claim when it becomes an investment property.

You should consider the following:

- Make sure you use an offset account, not a redraw account. They both save you the same interest. However, the tax office sees redraw accounts very differently. This could affect your tax deductions when you convert this into an investment property (see chapter 5).

- Have an interest-only loan for your main home loan. Put any extra savings that you haven't paid off the principal into your offset account and allow that balance to build. (Though the temptation to spend might be greater, which you will need to weigh up.)

- Consider using a lender that allows you to have multiple offset accounts, so that you can still park your longer-term savings in a separate account from your normal savings.

- Keep receipts for all major improvements to the house. They might become tax-deductible when you rent the house out.

The distinction between offset and redraw is particularly important from a tax perspective.

This sort of structure will allow you to take all of your savings to your new home when you move into it. For example, say you buy a home for $500 000 with a $450 000 loan, using the structure I've outlined here. Over the next five years, you manage to save $90 000 in your offset account, so you're only paying interest on this loan for $360 000 ($450 000 minus $90 000).

Then you buy another home. By using the offset account correctly, you can take the $90 000 as a deposit or equity for the new home. And when you convert it to an investment property, you will get a tax deduction on the interest for the full $450 000 again.

(If you had used a redraw account, the ATO would allow a tax deduction on the interest of $360 000.)

If you eventually decide not to rent it out, but to sell it (to take the equity with you to your new property), the above structure will mean that you won't be in a worse position — no damage will have been done, if you have been able to save the money and not spend it. And at any time, you can switch to principal and interest, or make extra repayments into your redraw account.

Your first investment property

The structure of the loan for your first investment property will depend on a few things. Do you already have a home loan? If not, are you intending to buy a home in the future? If owning a home to live in is not part of your plans, then is this likely to be your only investment property, or are you looking to build a portfolio?

Already have a home

If you already have a home loan, your aim should be to have a structure that allows you to maximise the tax deductions on your investment property, while minimising the amount of interest you pay on your home loan (which is not a tax deduction).

Some people see this and believe that it must be trickery — how can you pay less on your home loan? It's this simple. If you had an extra $10 000, would you use it to pay down your home loan, or your investment property loan?

Your home loan, of course.

So, then, it's just a matter of creating that extra $10 000 (or $1000, or $5000 or $20 000 — the amount doesn't matter). How do you do that?

Take an investment property loan of $400 000, on 6.5 per cent over 30 years. If the loan is principal and interest, the repayments would be $2528 a month. If it is interest-only, the monthly repayment would be $2167. The difference is $361 a month, or $4332 a year.

The owners of this investment property also have a home loan of $450 000, on which the monthly repayments are $2844. By diverting the extra $361 a month into paying down their home loan, they will shave nearly eight years (seven years and 11 months) off their home loan and save approximately $176 000 in interest.

They will also benefit in other ways. They will maintain higher tax deductions on their investment property, which could also be directed to paying down the home loan faster.

It's powerful stuff.

Figure 7.3 (overleaf ) differs from the previous figures in that there is rent coming in to the offset and an investment mortgage to pay also.

Figure 7.3: setting up your offset account for a property portfolio

So, in order to take advantage of these potential benefits, you are looking to use this model to set up your loans in roughly the following way:

- on your investment property, you pay interest-only

- on your home loan, you pay principal and interest

- have all incoming money paid into your offset account, including rent from the investment property

- set up direct debits from your offset account for bills, including the credit card, to be paid on their due dates.

Looking to buy a home after investment property

This is the situation I found myself in. I told Mrs DebtMan (then my girlfriend) that I wanted to buy a home. She said: ‘No, you can't buy a home until we can buy a home.' She was not long out of uni, had no savings and some credit card debt.

But I desperately wanted to buy. I gave her one year to save for a home, but I decided I would buy an investment property in the meantime. And off I went.

I had two choices. I could use all of my then savings to keep the loan on the investment as low as possible. Or, I could get a larger loan and hold on to some of my savings, so that I could put it towards buying our home (which happened about 15 months later).

The second option will often work better, although consideration always needs to be given to the fact that if you buy an investment property first, you will not get the benefits of first-home owner grants, or first-home buyer stamp duty concessions (see chapter 5 for a bigger discussion). Here's why.

Let's say a couple has $110 000 in savings. For whatever their personal reason, they want to buy an investment property first, then a home in a year or three.

The investment property is worth $450 000. They could use their entire deposit to effectively pay the 20 per cent deposit (to escape lender's mortgage insurance) and stamp duty, leaving them with a loan on the investment property of approximately $360 000.

Or they could pay for 10 per cent ($45 000), plus stamp duty and costs (say $20 000), which would use approximately $65 000 of their savings, leaving $45 000 in savings for when they buy their own place. They should pay interest-only on the debt of their investment property and save what they would have had to pay in principal payments towards their deposit for the new home they will eventually purchase.

And they can start to build their savings again.

Other advantages and disadvantages:

- Advantage: They have maintained a higher tax-deductibility on the investment loan.

- Advantage: The eventual loan for their home, which is non-deductible, will be lower as a result.

- Disadvantage: They will have to pay some LMI for borrowing more than 80 per cent of the value of the investment property.

Investment only

You're not looking to buy a home. You're happy to rent forever (or for the foreseeable future anyway) and want to buy an investment property, or potentially build your investment portfolio.

Years ago, banks wanted you to be paying principal on at least one of your loans, but now they are usually happy for you to pay interest-only on your investment loans. If your bank isn't, another one will be.

If you just want to buy one investment property and won't be buying a home, then your choices are to either pay interest-only and use your money to build investments elsewhere (or enjoy a nicer lifestyle), or pay principal and interest to help build your equity faster.

It can still be a good idea to pay interest-only and use an offset account for your savings, which will minimise the interest you have to pay each month.

Building a property portfolio

And if you're looking to build a property portfolio … getting the structure right early is particularly important.

Building a valuable property portfolio is usually a decades-long process. It starts with a single property, for which the rules I've just outlined generally apply. If you have a home, use the offset account to keep interest payments on that debt to a minimum.

If you don't own a home, but intend to in the future, it is crucial that you use an offset account, and not a redraw account (as explained in chapter 5).

Multiple offset accounts — the new star on Mortgage Street

In recent times, banks have started offering packages with multiple offset accounts to assist you with managing your own money, which work together to reduce interest on your loans.

For example, you might have, say, three offset accounts for your home loan of $530 000. The first account might have $15 000 in it, the second has $5000 and the third has $8000. For that month, you will only pay interest on $502 000 ($530 000 minus $28 000).

This is a great innovation in banking and allows for many different types of money personalities, particularly couples, to benefit from offset accounts.

Yours, mine and ours

From my experience as a financial adviser and mortgage broker, I understand that it's actually the norm for couples to have separate money. They will often have an account for each partner and then potentially a joint account. The joint account is the account from which shared bills are paid and they often both pay a weekly or monthly amount into that account for that purpose. But they still have their own money in their own accounts for their own spending.

Unfortunately, if there is only one offset, but three accounts are required, then there is always going to be money that is in regular savings accounts, earning interest on which tax has to be paid.

Being able to have multiple offset accounts attached to the one home loan means a couple can have separate money, if that's what works best for them, but still have every dollar saving them interest on their home loan.

Separate accounts

Multiple offset accounts can also work well for people who like to have money separated into different accounts for different purposes. These could be for any reason, including for travel, medical costs, emergency funds, to buy cars, to pay bills and so on.

Obviously, multiple offset accounts are often perfect for organising your finances like this (though some of the providers have rules about how much money must be deposited in each account each month to avoid fees). But having two or three offset accounts can be useful for, particularly, having separate accounts for general banking, and short-term and long-term savings.

Having multiple banking partners

There are often good reasons for having all of your banking with one lender. Often, for an annual fee of $200 to $400, you can get very good value from a banking package, including loan discounts, free banking, free credit cards, and so on (see the section on professional packages in chapter 4).

However, there will be times when you both want to deal with multiple banks and need to deal with multiple banks.

This could be because your existing bank won't lend to you at the time that you need the money, or they won't lend for the particular property you want to buy, or any one of a number of different reasons. Sometimes, the bank you wish to deal with will come back with a valuation that doesn't suit, or make possible, what you want to do.

Some of my clients have wanted to grow their property portfolios fairly aggressively. And, at some points, their preferred lender has let them down. Often, you will need to use another bank who will play ball on terms that are acceptable to you.

You might develop a good relationship with a particular bank. But don't swallow everything they say hook, line and sinker. Banks do take their clients for granted — don't expect them to ever volunteer to reduce the interest rate you're paying, unless you threaten to leave or complain occasionally — and sometimes they need to show some love to you, or you should threaten to go elsewhere.

Structuring of multiple loans

For those who are buying a second property — whether that second property is going to be a home or an investment property — some thought needs to be put into the structure of the loans.

As you're building an asset base of properties and associated debt, important questions need to be answered along the way, including whether your relationship will be with one bank or many.

But before we go on, there is something important that you need to understand, regarding the ways that security can be taken by a bank to cover their loans.

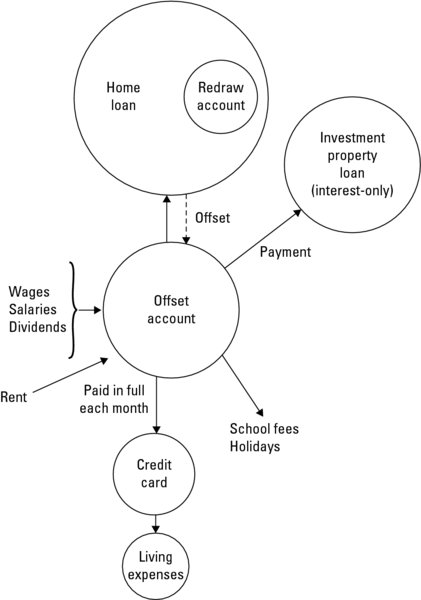

Cross-collateralisation

Cross-collateralisation means that a bank holds security over more than one property for a loan. Most commonly, a borrower might have, for example, two properties and there are two loans on the properties. The securities on the two properties are crossed, which means that the bank can sell both properties, if it needs to, to settle the loans.

This can be a particular problem when a borrower deals directly with a bank. Banks seem to have as a default setting that they suggest cross-collateralisation to clients. And you can understand why — they have security over more properties and that gives them greater assurance that they can get their money back if trouble with the borrower is afoot.

If it can possibly be avoided, it should be. If you have multiple properties and growing equity in those properties, then it can usually be done. And, if you have sufficient equity, you can often just insist that the properties not be cross-collateralised. Figure 7.4 shows how loans and properties can be interconnected via cross-collateralisation.

Figure 7.4: an example of cross-collateralisation

Stand-alone loans

How can cross-collateralisation be avoided when you're borrowing more than 100 per cent of the property (to take in stamp duty) and if you want to avoid LMI? Potentially by structuring it as two loans against separate properties.

Say your home is worth $800 000 and there is a home loan of $250 000 on that. You wish to purchase an investment property for $500 000, with total debt for that purchase of $530 000.

This property loan can be structured by having three loans over the two properties. There's the existing home loan, then a loan for 80 per cent of the value of the investment property against that property (loan of $400 000), with the remaining $130 000 against the home. The final $130 000 will still be tax-deductible debt, because the purpose of the loan is for the investment property. In table 7.1 I show how this loan can be structured without having to incur lender's mortgage insurance, despite technically borrowing more than 100 per cent of the value of the investment property.

Table 7.1: stand-alone loans

Value |

Loan |

Loan-to-valuation ratio (LVR) |

|

| Home | $800 000 |

$250 000 | 31.25% |

| Home | $130 000 | 16.25% | |

| Investment property | $500 000 | $400 000 | 80.00% |

| Total | $1 300 000 | $780 000 | 60.00% |

In this example, the total loan to valuation (LVR) over all of the properties is only 60 per cent. There is no LMI to pay, because the combined debt on each property is below 80 per cent.

Lender's mortgage insurance (LMI)

LMI has been raised many times throughout this book. It's a nasty, often large, charge that is essentially the bank getting you to pay the premium for an insurance policy for them. This is in case you fail on your loan and the bank has to sell your property, but the property isn't worth enough to repay the loan.

The reason LMI is needed is probably best explained with an example. Let's say Ajit and Susan bought a home for $500 000 and borrowed $450 000 (90 per cent of the value of the property).

A year after they bought the property, the economy turns south. As the result of the downturn, Ajit loses his job and they can't afford to continue paying the mortgage. The bank moves in to sell the property to recover the loan. However, the downturn has affected property prices and the property only fetches $410 000 — not enough to repay the $450 000 borrowed.

Lender's mortgage insurance then allows the bank to make a claim with the mortgage insurer against the loss of that $40 000 and other costs.

As a result, anyone who borrows more than 80 per cent of the value of a property is generally liable to pay LMI. This charge will be passed on directly by the bank to the borrower.

The rate at which LMI is charged is exponential and can also jump far higher when the value of the property being purchased increases. In table 7.2, we use the $500 000 purchase price from our previous example.

Table 7.2: lender's mortgage insurance (LMI) premiums

| Loan-to-valuation ratio (LVR) |

Loan amount |

LMI premium |

LMI premium as % of loan |

| 80% | $400 000 |

$0 |

0% |

| 81% | $405 000 |

$2405 |

0.594% |

| 82% | $410 000 |

$2435 |

0.594% |

| 83% | $415 000 |

$2592 |

0.625% |

| 84% | $420 000 |

$3700 |

0.881% |

| 85% | $425 000 |

$4006 |

0.943% |

| 86% | $430 000 |

$4716 |

1.097% |

| 87% | $435 000 |

$4813 |

1.106% |

| 88% | $440 000 |

$6132 |

1.394% |

| 89% | $445 000 |

$6706 |

1.507% |

| 90% | $450 000 |

$8533 |

1.897% |

| 91% | $455 000 |

$12 917 |

2.839% |

| 92% | $460 000 |

$13 343 |

2.901% |

| 93% | $465 000 |

$15 252 |

3.280% |

| 94% | $470 000 |

$15 416 |

3.280% |

| 95% | $475 000 |

$17 242 |

3.630% |

Note: For consistency, we have used the same major lender in the above calculations, with a house purchased in Victoria. Other banks may use insurers whose charges and percentages might differ from those above. LMI-charge percentages may increase for higher-priced properties.

As you can see, it increases relatively smoothly ... until the loan goes above a 90 per cent LVR. Above 90 per cent, LMI spikes, as insurers and banks charge for the increased risk of loan failure. Understand that this is an insurance premium that does not cover you. The bank is passing on the cost of the insurance premium it has to pay to cover itself against your potential failure to repay the loan.

Obviously, if you're going to borrow more money, your repayments are going to be higher also. But LMI is the really significant difference between buying your first home sooner rather than later. Most of the rest of the costs of purchase do not change depending on the amount borrowed.

If you have the patience to save 20 per cent plus legals, then that is a great target to achieve and all power to you. For most, having enough to ensure your loan is below 90 per cent of the property's purchase price (and therefore with a reduced LMI premium) will be sufficient and will allow people to purchase their homes sooner.

LMI: Advantages for buyers

LMI means that buyers can purchase properties sooner than they might otherwise be able to. If LMI didn't exist, banks would probably insist on minimum deposits of 20 per cent plus stamp duty and costs.

With many lenders, the actual LMI premium can be capitalised — that is, it can be added to the loan. In our previous example, the $450 000 loan would become a loan of $458 533.

For investors, if the LMI premium is added to the loan, the interest on that premium therefore becomes a tax deduction (a small benefit that will add up over the years).

Another reason for paying LMI could be in keeping some of your money for yourself, as raised earlier in this chapter, potentially to fund your own home purchase.

That is, if you had $130 000 in savings to buy a $500 000 investment property, but you were also wanting to buy a home in a year or so, then you might only use $80 000 of those savings to pay a 10 per cent deposit and cover your stamp duty, leaving you with a loan of approximately $450 000, which would require paying LMI.

But it would allow you to keep $50 000 in savings for your future home. This is something that needs to be weighed up by individual circumstances.

Property purchasing principles

It's not all about the house and the garden! Those attributes for the property are really important, either for you to live in or for you to make money from as an investment property.

But there are plenty of other 1 percenters that you need to get right. And those 1 percenters include making sure you get both the ownership and banking structures right.

These are not matters that you want to get wrong, as the financial consequences can be devastating. They can potentially raise the risk of you losing your property, can cost tens of thousands of dollars to fix and, sometimes, cannot be fixed at all and just become an expensive black hole for cash.

Don't risk it. Don't do this on your own unless you're absolutely certain that you've got it right. You're far better off talking to the required professionals — be they mortgage brokers, financial advisers, accountants or solicitors — to get personalised advice than to risk getting it horribly wrong.

And just to ram it home … here are the key points to take away from this chapter.

- Failure to properly structure your loans can end up costing you a lot of money — it really pays to take the time to get it right.

- Whose name is on the title, whether you're buying alone, with a partner or family or friends, is an important decision with many potential repercussions.

- If you are going to pursue a multi-person investment property, make sure you have a proper written agreement about the various factors involved in maintaining an investment property.

- Joint tenancy is one way to structure a multi-person investment, but it works best for two individuals with similar incomes. When one owner in a joint tenancy dies, their share is automatically divided among the remaining partners.

- Tenants-in-common is another option, where not all partners have to have equal portions of the property, and the partners can technically sell at any time or leave ownership of the property to whoever they desire in their will.

- Other ways to hold property include SMSFs, trusts, partnerships and companies.

- The structure of your debt is incredibly important to get right, and whether it's your first home, whether you plan on turning your home into an investment property, or it's your first investment property, different factors will have to be taken into account.

- If you already have a home, are looking to buy your home after your investment property, are only planning on owning investment property, or are planning on building a property portfolio, your situation needs individual consideration.

- Loan products with multiple offset accounts can be great tools for organising your finances.

- Sometimes multiple banking partners will be required over the life of your property investing.

- Multiple loans will be required if you want to invest in multiple properties, which involves more structuring considerations.

- You can secure multiple properties through cross-collateralisation or through stand-alone loans.

- Lender's mortgage insurance is the cost of the insurance premium the bank has to pay to cover itself against your potential failure to repay the loan; it passes that cost on to you.