3.1 INTRODUCTION TO PART 3

In this final Part, we get to apply the essence of NLP, established in Part 2, to the behavioural competencies required for effective delivery, established in our review of the role of BAs in Part 1. In my experience, NLP is the most effective toolset for effecting personal change and developing soft skills. Study and practice of these tools and techniques, ideally with coaching and practical training support, will help you to become even more agile in your behaviours, approach and mindset.

The soft skills described in the following sections are not only very important to BAs, but are transferable to other domains including most aspects of your personal life. Of the top 14 most searched topics in People Alchemy for Managers,1 13 are included in this set.

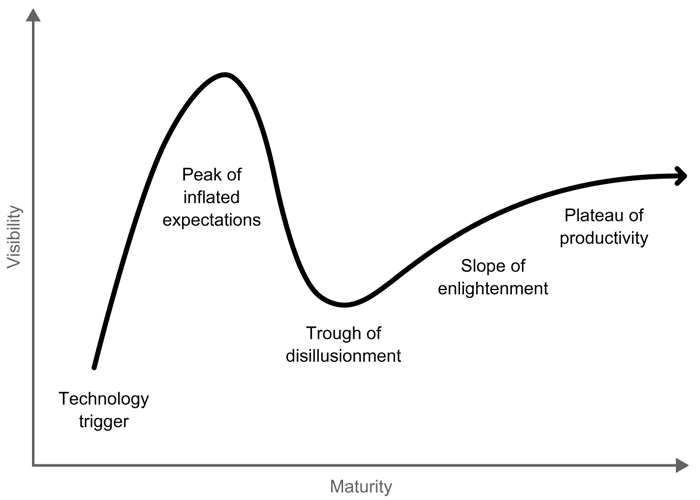

Change management is on that list, and one of the top three headline management issues for leaders in a 2014 BCS survey on IT trends2 was business transformation and organisational change. As I was coaching on transformational change while drafting this book, and it was apparent that a lack of awareness of breadth and depth in change management contributes to high failure rates, I have included a large section on transformational change to give an overview of successful behaviours and tools (see Section 3.18).

It may have come as a surprise to many while reading Section 2.6, that our conscious mind is not actually in charge of what we do. I think of it as the user interface to the complex biological computer that sits behind. I wasted many years trying to intellectualise myself into changing. What we will be changing with the tools and techniques in this Part are behaviours/meta-programs long embedded in the subconscious mind. Many of us working as coaches and counsellors spend a large proportion of our time and effort distracting and disengaging the conscious mind in order to get direct access to the subconscious where we can facilitate change. Hence, when practising exercises like these, disengage your brain – do not think, just do!

Knowing is not enough, we must apply. Willing is not enough, we must do.

Bruce Lee

3.2 ADOPTING AN ATTITUDE OF CONTINUOUS PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT

Be a yardstick of quality. Some people aren’t used to an environment where excellence is expected.

Steve Jobs, Apple founder and Zen Buddhist

Continuous professional development was specifically mentioned in several competency frameworks for BAs reviewed in Section 1.4.2. In this section we will explore what that means, over and above attending talks and seminars.

In Part 1 I mapped the behavioural competencies for effective BAs onto the EI framework. In subsequent sections, I will demonstrate that NLP can be used to develop all aspects of EI, including those supporting effective business analysis.

3.2.1 Increase your emotional intelligence

EQ, far more than IQ, ordains success, and it can be trained.

Victor Serebriakoff, honorary international president of MENSA, in the Foreword to Self-scoring Emotional Intelligence Tests3

Around 1995, while completing an executive MBA, I came across a newly published book on EI.4 I read the book with great interest and, like Victor Serebriakoff and probably most of the millions of others who read this bestseller, I became convinced that EI was the best indicator of future levels of success in the real world. This has been borne out by many studies, including the lifetime tracking of America’s most intelligent kids through school and their careers. That study concluded that, above the modest intelligence equivalent to a good college degree, your career progression is strongly dependent on your EQ rather than your IQ. This is probably true of your life satisfaction too.

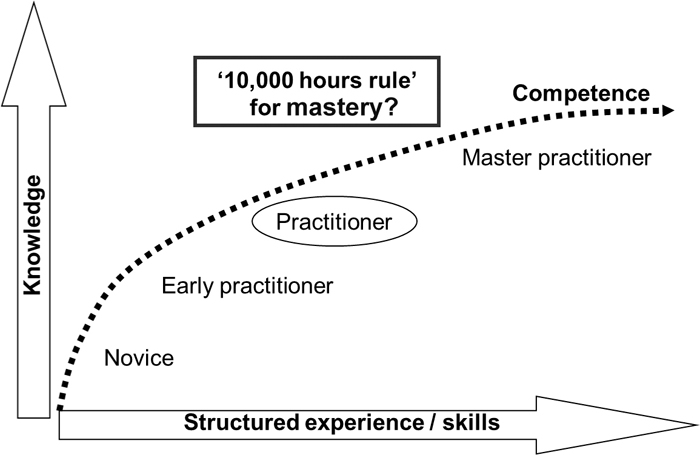

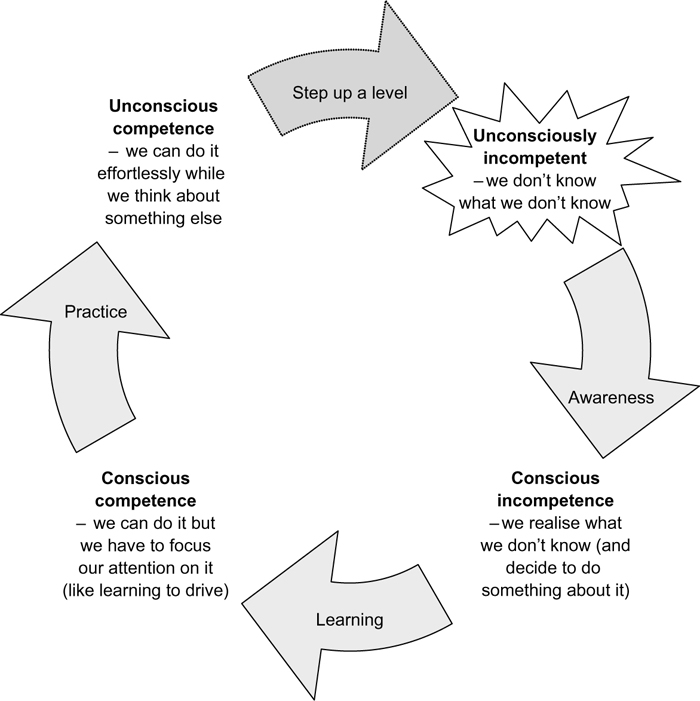

In Malcolm Gladwell’s bestselling book, Outliers: The Story of Success,5 he illustrated quite convincingly that success in any sphere is mostly down to EQ and structured practice. Indeed, it was this book which established the ‘10,000 hours rule’ of experience and structured practice required to achieve mastery in any discipline (see Figure 3.1). Do you think this is true for business analysis?

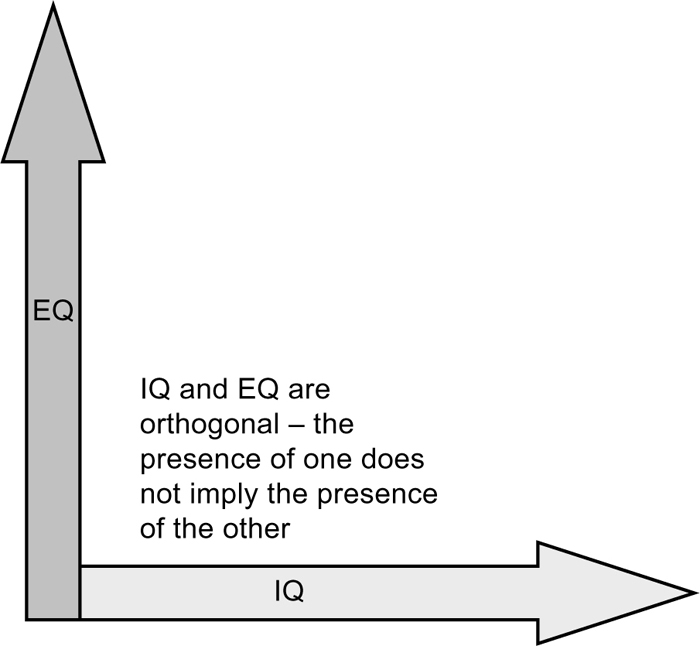

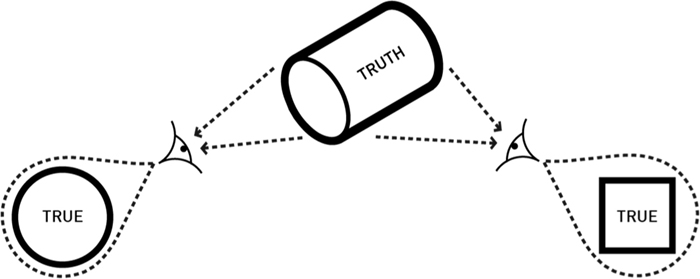

Gladwell illustrates this theory with a story about Christopher Langan, assessed as the world’s most intelligent person with an estimated IQ of 200, the maximum on standard scales. (For comparison, Einstein had an IQ of ‘only’ 150.) Yet he could not complete his college studies, hold down a job or a relationship. Gladwell parallels this with the story of Oppenheimer, the scientist put in charge of perhaps the biggest and most complex of mega-projects, the Manhattan project to develop the atomic bomb. Oppenheimer was no saint, and was caught poisoning his professor and thus putting him in hospital. Yet he was able to talk his way out of any situation and influence those around him with great success (see Figure 3.2).

Figure 3.1 Many hours of experience and structured practice are necessary to develop behavioural competencies

Figure 3.2 EQ and IQ are orthogonal

Gladwell concluded that practical intelligence includes ‘knowing what to say, to whom, knowing when to say it, and knowing how to say it for maximum effect. It is procedural.’ Do you think that ability would be useful to you and those around you?

The last clause, ‘It is procedural’, is particularly significant. When I finished reading that first book on EI I was convinced of my need for development in this area. Unfortunately, as I turned the last page, I realised that the author was merely noting its impact, and had no practical method of improving it. In fact, the general consensus at the time was, like IQ, EQ was more or less fixed. Fortunately, they were wrong, at least about EQ.

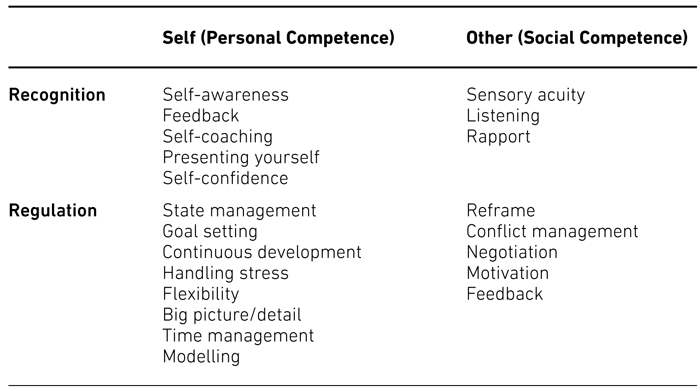

In this book I outline a very effective approach of developing all the areas of the EI framework. The following sections illustrate techniques for developing your self-awareness, managing your emotional state, helping you to be more aware of what is going on around you including other people’s drivers and levers, and how to influence others through your use of language, all of which will help you to be a more effective BA. These aspects are mapped out in Figure 3.3.

Figure 3.3 Skills for knowing and managing self and others

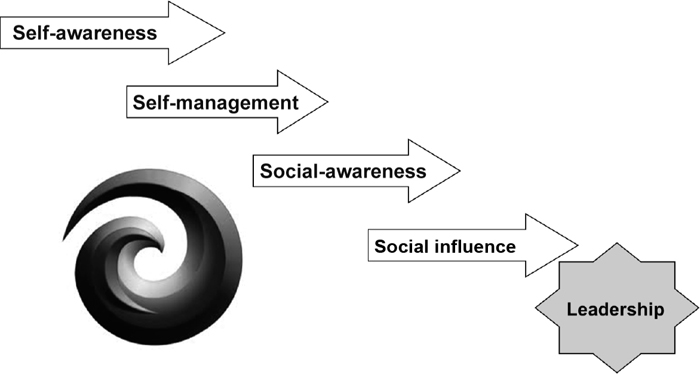

Of course, as we set out, we need to do this in an agile way, cycling through capability levels and embedding new behaviours. As described in Section 1.4, we can even base-line EQ using established methods and demonstrate quantifiable improvements (see Figure 3.4).

There are no limits. There are only plateaus, and you must not stay there, you must go beyond them.

Bruce Lee

Figure 3.4 Emotional intelligence can be improved through a structured approach

3.2.2 ‘Sharpen your tools’

Perfection is not attainable, but if we chase perfection we can catch excellence.

Vince Lombardi, American football player and coach

In Covey’s book, The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People,6 his last habit was what he refers to as ‘sharpening the saw’. I put it as my first behaviour because if we cannot motivate ourselves towards personal improvement then the rest of the book is wasted reading. I relate it by paraphrasing his story:

A man walks to work and notices another man sawing a tree. On the way home he sees that the man is still sawing the same tree. He suggests, ‘Have you thought of sharpening your saw?’ The man replies, ‘I don’t have time to sharpen my saw, I am too busy sawing this tree!’

In my professional life, I often see people who are too busy with the day job to invest in making the day job easier, that is, by developing themselves in parallel through new skills and tools. What proportion of your time do you spend ‘sharpening your tools’?

In my work with the professional bodies, we spent a lot of voluntary effort bringing in a wide range of quality presenters to pass on their substantial experience, but statistics across professional bodies show that engagement with members is consistently below 10 per cent. So, some 90 per cent are always too busy sawing the tree. Bearing in mind that membership of professional bodies is low in the first place where it is not a de facto standard, this means that only a small percentage are actively seeking ongoing development. But do not worry, you picked up the book and so are in the few who want to sharpen the saw. NLP is sometimes called the search for ‘the difference that makes the difference’, so here is the opportunity to really sharpen your saw!

3.2.3 You are the project

We should not judge people by their peak of excellence; but by the distance they have travelled from the point where they started.

Henry Ward Beecher, former US congressman and social reformer

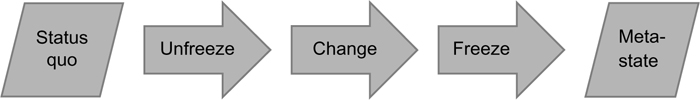

Having spent so much time in change management, I often think of myself as a change management project. As with many change management projects, it is a journey rather than a destination, with many ‘meta-states’ along the way where we pause to consolidate improvements, having achieved our outcomes for the current phase.

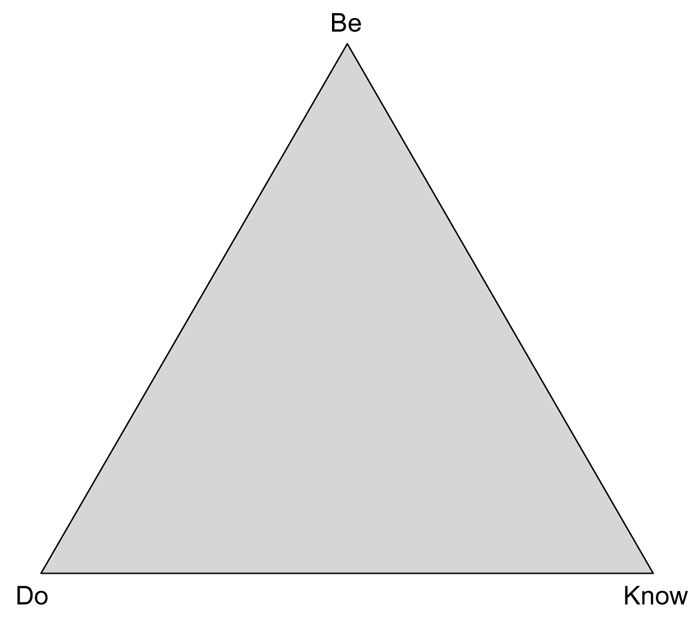

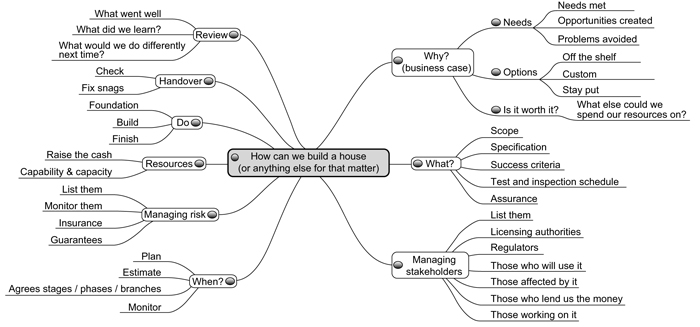

Figure 3.5 The DIY change project

What you get by achieving your goals is not as important as what you become by achieving your goals.

Zig Ziglar

The more naive recruitment agencies ask for BAs who have worked on exactly the same type of project in exactly the same sector, using the same solution vendor, and so on. In NLP we refer to the sameness / difference preference meta-program. People preferring sameness make good operational managers but are not so good at facilitating change. People sometimes say they have 10 years’ experience, but in reality they may have been doing more or less the same thing for 10 years and learned little since their first year.

To develop your potential, seek out challenges and stretch your zone of comfort. It is not necessary to change sector or even employer to get variety, just seek out novelty and set yourself personal development objectives at the start of every assignment.

Active engagement with professional bodies and communities of practice help enormously to structure your development and provide resources and mentoring.

3.2.4 Believing in yourself and removing limiting beliefs

There is a difference between wishing for a thing and being ready to accept it. No one is ready for a thing until they believe they can acquire it. The state of mind must be belief, not mere hope or wish. Open-mindedness is essential for belief.

Napoleon Hill, author of The Law of Success

Dale Carnegie said: ‘In order to get the most out of this book, you need to develop a deep, driving desire to master the principles of human relations.’7 That is good advice, but how do we develop a deep desire? Reading that statement on the page will not change our identity, beliefs, motivating values, behaviours or meta-programs. So how do we develop that motivation and take away our limiting beliefs?

Beliefs are not fixed, but are plastic and fluid. If we choose to, we can change them at will.

If your mind can conceive it, and your heart can believe it, you can achieve it.

Reverend Jesse Jackson

In Section 2.7 we discussed beliefs. These are usually buried deep in our psyche and we are not aware of them ourselves. They are often evident to others via our language and behaviours. Expressions like ‘I am bad at exams’, ‘I am not good with stakeholders’, or ‘I will never be a good business analyst’, do not just fall out of our mouths, but actually represent deeply held beliefs. We all have these types of thoughts in our psyche to a greater or lesser extent at some time or other.

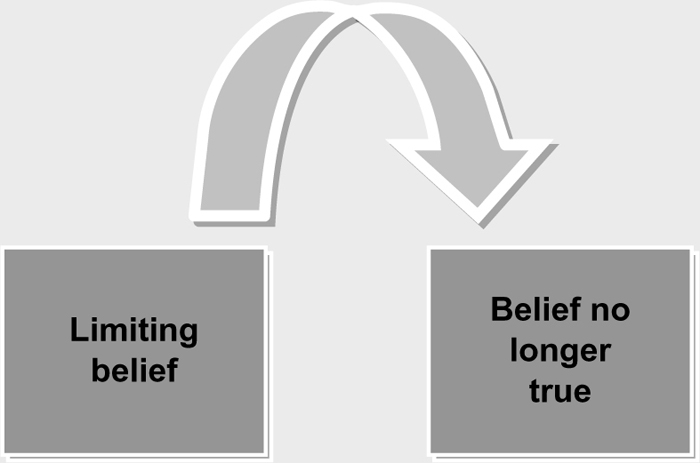

Exercise 3.1 Changing limiting beliefs

Sub-modalities were introduced in Section 2.12. The activities in this exercise, that is, changing sub-modalities, are analogous to the very successful fast phobia cure that many of you may have seen on TV carried out by the likes of Paul McKenna. This very visible demonstration of belief change was also the professional starting point for NLP guru Anthony Robbins.8 The exercise is based on the NLP presupposition that we can change the meaning of memories by changing the way we store them and the way that they are represented.9

- Think of a recent scenario where the outcome has not been satisfactory. What were you believing about yourself that created the outcome that you got?

- Think of the limiting belief that you would like to change.

- Close your eyes. Create a picture as you think about it.

- Explore all the sub-modalities (pictures, sounds, feelings).

- Open your eyes and note down the sub-modalities of the limiting belief (a check-list is shown in Figure 2.14).

- Think of a belief that you once held, but that is no longer true for you.

- Close your eyes and bring up a picture of this belief. Concentrate until it is vivid.

- Explore all the sub-modalities (pictures, sounds, feelings).

- Open your eyes and note down the sub-modalities within this belief.

- Work out which sub-modalities are different, and make a note of what needs to be changed.

- Close your eyes and bring back the picture of the limiting belief.

- Change the sub-modalities (from 3 and 4) in turn by making the changes to the picture.

- Open your eyes.

- Now think about the old belief that you used to have and notice how it is no longer limiting your behaviour.

If you believe you can, or believe you cannot, you are probably right. Henry Ford

3.3 KNOW THYSELF – DEVELOPING SELF-AWARENESS

He who knows others is wise; he who knows himself is enlightened.

Lao Tzu

Self-awareness was specifically mentioned in the review of competencies for effective BAs in Section 1.4 under the description ‘understanding how others see us’.

Self-awareness means understanding ourselves and our emotions and is the fundamental step to gaining emotional intelligence. Unless we have deliberately studied them, we are mostly unaware of most of our own core behaviours/meta-programs, or the fact that people have markedly different ones from ourselves, as we usually develop them subconsciously at an early age.

‘Know thyself’, said Socrates. But how many of us do? ‘Know thyself? If I knew myself I would run away’, said Von Goethe.

Here are a few descriptions from various texts which relate to self-awareness:

- reflective, that is, learning from experience;

- open to candid feedback;

- open to new ideas and perspectives;

- aware of our strengths and weaknesses;

- knowing our limitations, and knowing when and how to ask for help;

- able to admit mistakes;

- able to laugh at ourselves (before others do it for us).

In my straw poll of stakeholders, self-awareness was rated the number one characteristic for effective delivery. Hence it sits here, before any other aspect of personal development. If you do not appreciate it yourself, know that people who pay for your services do appreciate it. So do not run away.

I visited the head of capability at one of the big global consultancies several years ago and, rather than attempt to sell myself, I used a tried-and-tested consultancy technique. Since something had already got me through the door, they had obviously seen something they liked, so I asked, ‘What is it about me that you see of value to you?’ (Incidentally, this is a very good technique for convincing a potential client, as they will not resist their own assertions, whereas there will always be resistance to you making your own claims – a sort of one-up on the principle of using third-party advocates and references.) They replied, ‘You are very self-aware, and I want to develop that into my people.’

3.3.1 To see ourselves as others do

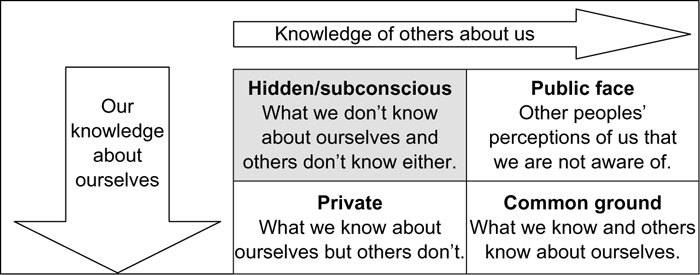

The technique of JoHari Windows10 is used to help organisations form a fuller picture of themselves. We can also apply it to ourselves.

In one of the four boxes in Figure 3.6, we have what we and others agree about ourselves, that is, largely factual. Then we have the stuff that only we know about ourselves, some of which we may want to keep private. Then we have the more interesting area of what people know or think about us, but we do not know or realise ourselves. This would be what our stakeholders know or think, but want to keep to themselves, or just that we have not got around to asking them. Companies spend a fortune on market research to find out what people think about them and their products. You may think that a company should know everything about its own products, but most realise that ‘the only reality is perception’. Companies also spend a fortune on consultancy, many to confirm what their own employees could have told them. Why?

Oh wad some power the giftie gie us

To see oursels as others see us!

It wad fra monie and blunder free us

An foolish notion.

Robert Burns

Aren’t we supposed to get feedback from our managers? How many managers loathe the annual ritual of giving feedback for fear of causing a scene, and often resort to selecting the middle performance marking and writing something mundane. Why? Because they assume that we do not know how we come across. Is it not much better to get into the routine of seeking feedback at the end of each piece of work rather than waiting for the dreaded annual review?

I was fortunate enough to be in a large multinational that adopted 360 degree appraisals for senior staff. This is where you ask peers, subordinates, managers and customers to give feedback via a standard process/tool and the results are fed back in a structured form. The results can be most illuminating, especially if you treat the exercise as a development opportunity and choose people to respond that you have had misunderstandings with, rather than only people you get on with in order to engineer a flattering score. (Hence it is a bad idea to link 360 appraisals with performance pay, as it ceases to be a development tool, which was its original purpose.)

There are many other tools that can help us to understand ourselves which all have value, including: Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI),11 occupational personality questionnaire (OPQ), de Bono’s Thinking Hats,12 and so on. There are also a number that are useful to understand our natural role in teams, including Belbin.13

When I was interviewed as a program manager for a Swiss airline company, part of the interview was with an occupational psychologist, which I was told was routine in Switzerland for senior posts. They ran a number of tests, and I agreed with the results of all of them. Most surprisingly, the handwriting expert was able to give a very detailed analysis of my inner workings that I agreed entirely with. Interestingly, I never went through any of these types of personality or behavioural tests when I went to high level clearance in the nuclear sector.

3.3.2 Behaviours as meta-programs

What does NLP have to contribute to all of these different types of assessment? Fundamentally, tests such as Myers–Briggs are assessing some groupings of behaviours/meta-programs. More than 60 meta-programs have been identified from composite behaviours.14 The basis of meta-programs was introduced in Section 2.8, but to recap a few points:

- Meta-programs are one of the sets of filters that we use to create our worldview and deeply affect how we interpret things, for example, whether the glass is half empty or half full.

- They are systematic and habitual, not random.

- They can be context specific; that is, different in work or in the home environment.

Exercise 3.2 Meta-programs for business analysis

In Figure 3.7 is a selection of the most relevant meta-programs to BAs. Although shown in pairs, they are analogue rather than binary. Think about your work context and score yourself – which end are you closer to? Remember, like MBTI, there is no right or wrong, just an understanding of your natural inclination; and, unlike the earlier story, it is possible to develop flexibility in your meta-programs if you choose to, as demonstrated later.

Having considered what our preferred meta-programs are, and what the alternatives are, we can use this information to develop more flexible behaviour.

Figure 3.7 Scoring your meta-programs

1 → 10 |

|

Proactive |

Reactive |

Initiates action. |

Analyses first then follows the lead from others. |

Towards |

Away from |

Focused on goals. |

Focuses on problems to be avoided. |

Motivated by achievement. |

|

Internal |

External |

Has internal standards. |

Gets reference externally. |

Takes criticism as information only. |

Likes direction. |

Match |

Mismatch |

Notices points of similarity. |

Notices differences. |

General |

Specific |

Likes to take a ‘helicopter view’ and gets bored with detail. |

Likes to work with detailed information and examples. |

Options |

Procedures |

Likes to generate choices. |

Good at generating logical flows. |

Good at developing alternatives. |

Likes to have processes documented. |

Associated |

Dissociated |

Feelings and relationships are important. |

Detached from feelings. |

Works with information. |

|

Task oriented. |

|

In time |

Through time |

Lives in the moment. |

Good at keeping track of time and managing deadlines. |

Creative but poor with deadlines. |

|

Self/Introvert |

Other/Extrovert |

Need to be alone to recharge batteries. Few relationships with deep connections. |

Relaxes in the company of others. |

Interested in a few topics but to great detail. |

Has a lot of surface relationships. Knows about a lot of things, not in detail. |

Sameness |

Difference |

Likes things to be the same. |

Doesn’t like surprises. |

Likes challenge. |

Looks for opportunities to try new things. |

Independent |

Cooperative |

Wants to work alone. |

Wants to work as part of a team. |

Wants sole accountability. |

Likes shared responsibility. |

Person |

Thing |

Oriented towards people and focuses on feelings and thoughts. |

Focused on tasks, systems, ideas, tools. |

People are the task. |

Getting the job done. |

3.4 DEVELOPING AGILITY IN APPROACH AND STYLE

It is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent. It is the one that is the most adaptable to change.

Charles Darwin

Speaking to colleagues about the trend towards agile development, we concur that, although some people, perhaps more detail, process and logic/AD oriented, are promoting defined methods for agile, it is more about having an agile mindset, as per the Agile Manifesto.15

In discussions with other coaches while developing the contents of this book, we reflected on what the most useful behaviours would be for effective BAs. We concluded that it was not particularly any part of the role, but, rather, the attitude and approach to the role itself.

If we could wave our magic wand, we would help BAs to recognise context and flex to the big picture at will from a natural bias towards detail. The main advantage of this would be when presenting to executive audiences. We cover techniques for ‘chunking up’ to big picture in Section 3.5.

Building on this would be practising adoption of the other person’s perspective. This is a true life skill and occupies much of the territory of the third quadrant of the EI framework on social intelligence. Not only are there benefits in understanding the other person, but also in being able to relate to them more effectively. We will practice tools for adopting the other person’s perspective in Section 3.24.3.

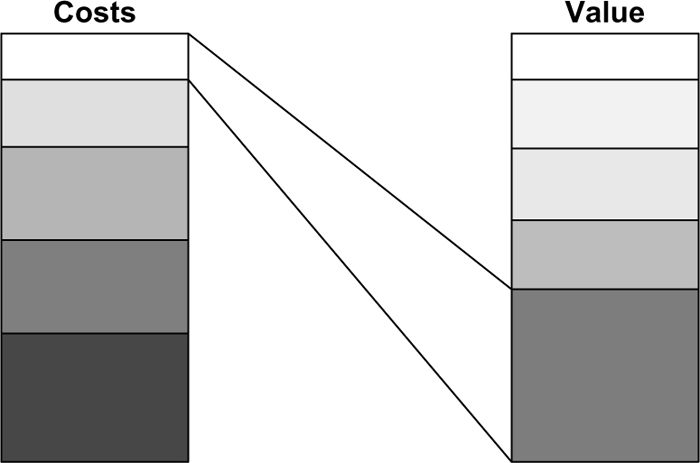

These two aspects together also help us to shift the focus from asset or process to business benefit, which is now included in the scope of BA competency frameworks. As in the current IIBA definition of the role of an effective BA, you need to act as a translator between the business and the delivery capability. To do this you must become fluent in both positions and adept at flexing between the different world-views, behaviours and language patterns. IIBA’s definition of the role of business analysis in v3 goes even further:

Business analysis is the practice of enabling change in an enterprise by defining needs and recommending solutions that deliver value to stakeholders. Business analysis ultimately helps organisations to understand the needs of the enterprise and why they want to create change, design possible solutions, and describe how those solutions can deliver value.16

When you ‘help the organisation to understand’, and ‘describe how solutions can deliver value’, you should provide the translation to their map of the world.

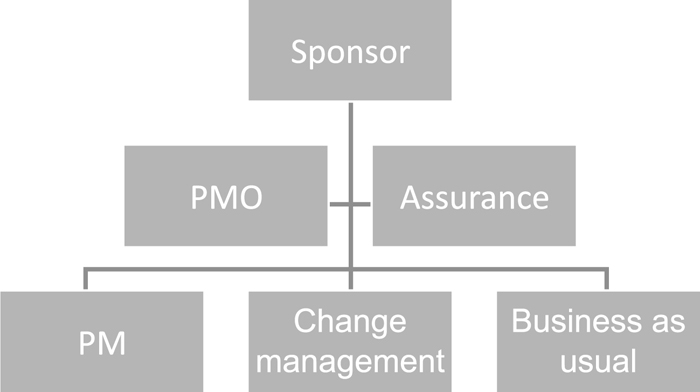

3.4.1 How to assure an agile approach by looking at behaviours

When I was a board member of the professional body, my remit was to sponsor and develop best practice groups, and we launched one on Assurance in 2006. Some excellent work has come out of the group since then, but the growing popularity of agile methods poses some problems for traditional thinkers. For a waterfall approach, assurance is quite straightforward in that you develop a specification and then deliver to it against an agreed plan and budget. For agile, however, the timescale is fixed, our resource pool is assumed fixed, but our scope is variable, and we do not have a forward plan showing all of the activities and when they are supposed to happen. So, how can you and your client have confidence in an agile approach?

Exercise 3.3 Assuring agile behaviours which underpin success

Given that luminaries in the agile world concur that agile is more about mindset than toolset, it follows that, for assurance to be forward looking and provide a measure of confidence in delivery, we should focus on behaviours. So, which behaviours do you think are important to the success of an agile approach? I have started the table in Figure 3.8 from statements in the Agile Manifesto; what behaviours would you add for your team?

Figure 3.8 Agile behaviours underpinning success

Focus on individuals and interactions (over processes and tools)

Customer collaboration (over contract negotiation)

Responding to change (over following a plan)

In the exercise in Section 3.6.4 on developing your team charter, it is not enough to write down only what behaviours we would expect; how would you be able to tell whether people were exhibiting those behaviours? What evidence would you like to see in your team for agile working?

3.4.2 Becoming agile – adapting style to context and environment

Insanity is continuing to do the same thing but expecting to get a different result.

Albert Einstein

One of the presuppositions of NLP, based on the field of cybernetics, is: ‘The person with the most flexibility in a system controls the system.’ This is not about stopping what we were doing. As another presupposition states, ‘All behaviours are useful in some context’, otherwise we would not have embedded them in the first place. When we have problems with behaviour, it is usually that we are transferring a strategy that was successful in the past to a context where it is no longer useful. ‘Choice is better than no choice’; wouldn’t you agree?

Having worked out where your natural preferences are in Section 3.3 on self-awareness, you now have a picture of where you are naturally strong and where you might want to develop flexibility. Alternatively, you could just focus on your strengths and natural preferences.

When we are no longer able to change a situation we are challenged to change ourselves.

Viktor E. Frankl, published psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor

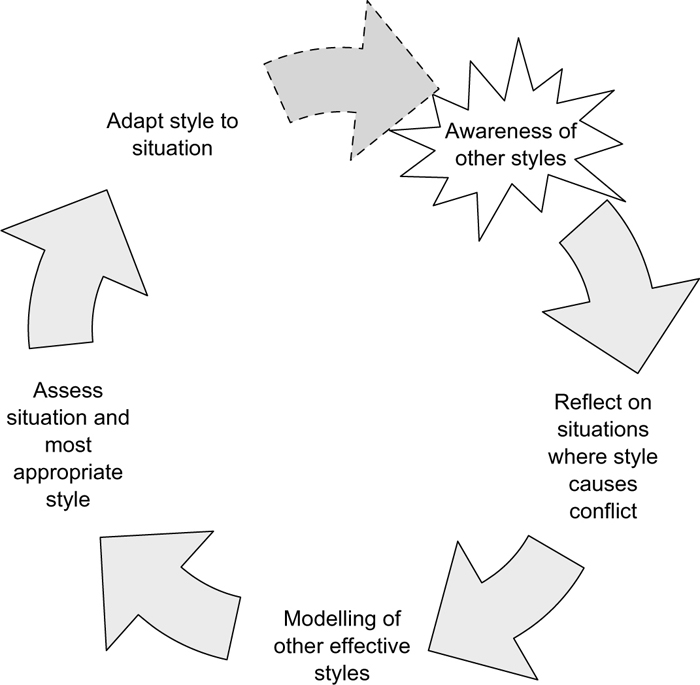

Figure 3.9 illustrates the cycle in which we can start to develop flexibility in behaviours.

Once I have identified a situation in which I am having difficulty, then I identify someone who has achieved success in a similar situation. Ideally, I will look for several people that have solved similar problems in different contexts and in different ways and try to identify common elements to form a new strategy. We can then feed this new strategy into the TOTE model described below, test if it works in a non-threatening environment, and go around the loop until we have sufficient improvement. As we shall see in Section 3.10 on modelling, it is something innate in our nature – NLP just helps to make it more explicit.

3.4.3 The TOTE model – a strategy for personal change

Everyone thinks of changing the world, but no one thinks of changing himself.

Leo Tolstoy

Figure 3.9 Adapting style to context

As human beings, we have strategies for doing everything in life, whether it is motivation, learning, relaxation and even finding love. When things do not work, it means that our strategy is not working in that context. For example, most of us would not talk to our boss in the same way we that talk to our kids, as the context and purpose is different. The TOTE model can help you to understand the current strategy you have, and if it is not working in this context, how you can develop a new strategy. The strategy may be one that is successful for you in another context, for example dealing with your spouse, or from someone that you observe as having success in this area. You may recognise that the TOTE model is widely used in testing, for example whether the code in a computer program actually achieves the desired outcome in real life situations. Here we are applying TOTE to your own strategies/programs to see if they are effective in the context you are applying them.

Exercise 3.4 The TOTE model for internal strategies

- Think of an outcome that you want to achieve and are having problems with. Maybe you do not seem to be able to get on with your sponsor, or maybe you have had a series of miscommunications with one user in particular.

- Test:

- Notice what is happening in the situation. What do you think about the other person? What do they think about you? Are there any peculiarities? Does it remind you of similar situations from your past?

- What would be the desired outcome?

- What are key differences between what happens and what you want to happen?

- What will you notice to be different when things happen the way that you want them to?

- Operate: The idea here is to generate different ways of doing things.

- Think of another area of your life where you deal with similar situations or where you have achieved similar outcomes.

- What were the key features of the successful behaviour?

- What are the main differences in behaviour? Maybe what you thought about the person, maybe tone of voice, maybe use of language such as motivation style, or even choice of words.

- Identify some aspects of your behaviour and actions in the problem situation that might be changed.

- Test:

- Ideally in a non-threatening environment or situation, test whether the revised approach has got you nearer to achieving your desired outcome.

- If the approach works to some extent, continue to cycle through the TOTE model until you are happy with the results.

- If the approach does not work then consider looking for external resources, for example modelling people who do achieve success in this area (see next example).

- Future pace. Think about a time in the future that you will have to deal with the same person in the negative situation. Imagine that you have all the new resources from (c); notice how you act differently and, therefore, how the situation will turn out much better.

- Exit:

- When you are happy with the results then the TOTE model is complete. Were your success criteria met?

I used to clash with the finance department on a regular basis. ‘Why did they need all this information from me, and why don’t they give me reports in the format that I want them?’ The finance department can be a strong ally, but they can also make a bad adversary. Things had to improve.

I realised that I did not appreciate the role of ‘bean counters’, and was going along to meetings expecting a fight in order to put them right. It had not even occurred to me to explore their map of the world, or understand why they were asking me to fill in forms. Outside this minor conflict, relations with others were good.

I decided that the desired outcome was that both parties had to be listened to (rather than me ending up shouting at them). Both parties smiling would be a good indicator of this, followed by common courtesies and show of appreciation for help. When I thought about the ‘test’ part of TOTE, I realised that the present state was vastly different compared to the desired state, that is, neither side was smiling.

I considered how I could reduce the difference between the two states and used the strategy that seemed to be successful for other requests for information, such as with railway enquiries or customer services. On comparison, the two similar situations could not have been approached more differently. My body language, use of words, tone, expectations, and so on were all at opposite ends of the spectrum.

To put this idea into action (operate), I translated the strategy across situations and made a non-urgent enquiry with accounts. (Fortunately, I was able to see a new member of the department, so the relationship was not tainted by previous experiences.) I merely asked for help on how I would go about getting financial approvals, how they could help me, pitfalls to watch out for, and so on. I hope you will not be surprised that the meeting took a completely different tone (test). Having given them personal and professional respect, we had a constructive conversation. Asking for help, instead of telling them what I wanted, removed barriers and built bridges instead.

I could exit as there was no difference between the present state and the desired state.

It was easy to visualise future meetings, where I would go to ask for help, and at worst be redirected (future pacing).

When I was later managing implementations for finance systems, I got to know the world of accounts, processes and financial governance. This gave me an understanding of why they were forced to act as they had. Even later, I ended up as program director with one of the major firms of ‘bean counters’, so we in fact became friends. (Mind you, I seem to have kept the old strategy for dealing with my own bank.)

3.5 SEEING THE BIGGER PICTURE WHILE MANAGING THE DETAIL

In order to properly understand the big picture, everyone should fear becoming mentally clouded and obsessed with one small section of truth.

Xun Zi

We often hear people talking about ‘needing to see the big picture’, but what are they actually talking about? Well, some people at work would naturally see a ‘helicopter view’ of a project, such as purpose, global budget, key stakeholders, rough duration and likelihood of success. Often, they will see this all together in a holistic picture with half a dozen key features. Others would ask to look into the detail of requirements and functional specifications. We need both types of behaviour to deliver a project, though these could be in different team members.

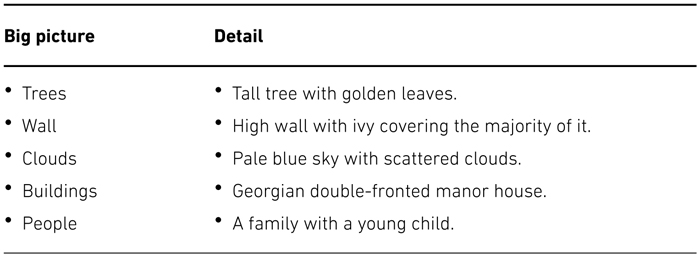

Before you read on, look out of the window for 30 seconds. Now quickly write down the first five things that you remember. Did your words show a clear preference?

Figure 3.10 Finding your preference

3.5.1 Chunking things up and breaking things down

Details create the big picture.

Sandy Weill, former chairman of CITI Group and author of The Real Deal

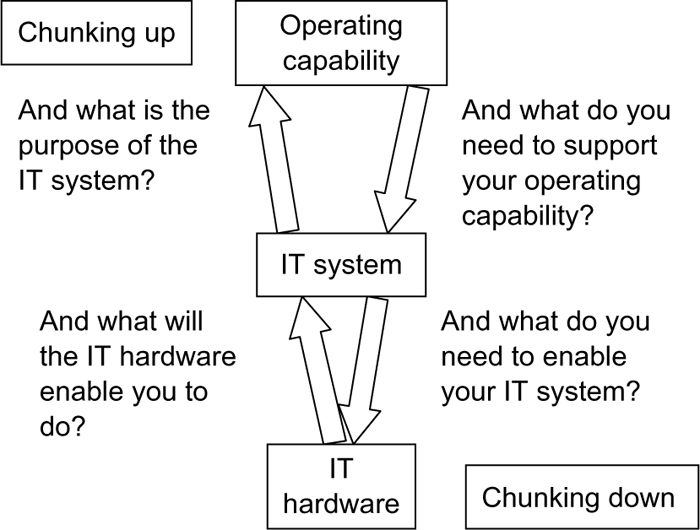

It does not matter where we start from in terms of preference for chunk size, as we can arrive at the same place. In NLP, the process of chunking is used extensively to get to the right level of information; for example, chunking up to arrive at a motive in order to establish alternative strategies, or chunking down to arrive at sufficient detail for an action plan. Both have a time and a place.

Nothing is particularly hard if you divide it into small jobs.

Henry Ford

Figure 3.11 Chunking up and down

In general, project management tools and techniques cater for the two perspectives, especially phasing of a project and use of work break-down structure. Indeed, on reviewing the UK nuclear industry’s £100 billion life-cycle base-line decommissioning program, the whole could be viewed as one entity, important to establish overall budgets and resources for approval, or drilled down through seven layers of work break-down to reveal individual discipline-based work packages in any one of dozens of programs.

3.5.2 Changing meta-programs

We have spoken about the need to develop flexibility, and nowhere is this more apparent than in relation to the meta-program for ‘big picture/detail’. Not only are some tasks more suited to one option than the other, but you will need to reflect the bias of your senior stakeholders when reporting to them and also balance this with the preference of your team.

Do not worry, though you probably have a strong preference, it can be changed at will. (Nearly all of us have a strong preference for using our right or left hand, but you can learn to brush your teeth with the other hand with practice, even though you would never be inclined to do so and it does not feel natural until you have made it routine.)

3.5.3 Communicating with big picture and detail

Do your key stakeholders have a preference for ‘big picture’ or ‘detail’? You are likely to have a mixture of both. You would normally expect to get more ‘big picture’ people higher up the organisation, but this is not always the case, especially where people are promoted within a discipline, for example IT, engineering or finance. Similarly, you would expect to get more ‘detail’ oriented people doing delivery, but I have been caught out by this when working in creative sectors such as digital media. If you do not communicate with them according to their preferences, then it is going to take a while to develop rapport. Have you ever tried to give a 20-page progress report to your sponsor, or five bullet points to an accountant?

Find out what your client’s preference is and communicate with them in their preference, both with written and verbal communication. If you cannot work out your client’s preference, then ask them: ‘How would you like me to present x?’ ‘How much detail would you like me to go into?’ Remember, if you are communicating with a detail oriented person, make sure that you do a thorough spellcheck or your credibility will be severely questioned. (When getting this book reviewed I picked a mix of types. Some advised that I was missing a section while others would pick up on grammar and spelling – we need both.)

Exercise 3.5 Listening and using appropriate vocabulary

Big picture |

Detailed |

Summary |

Precisely |

Overview |

Schedule |

In a nutshell |

First, second, next… |

Generally |

Plan |

3.6 GETTING RESULTS WITH DIFFERENT CULTURES

You would expect different cultures to develop different sorts of ethics and obviously they have; that doesn’t mean that you can’t think of overarching ethical principles you would want people to follow in all kinds of places.

Professor Peter Singer, philosopher at Princeton University

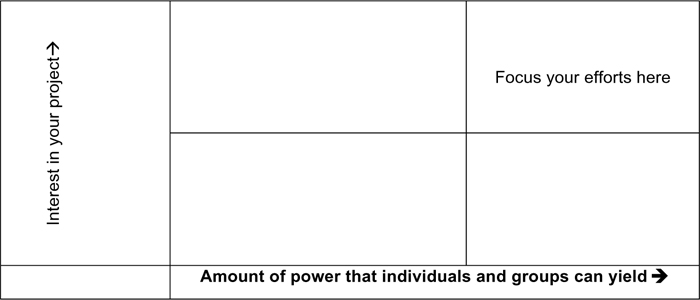

Cultural and political awareness were specifically listed in the review of behavioural competencies for BAs in Section 1.4. The wider topic of social awareness is one of the quadrants of the EI framework.

3.6.1 Better together

Coming together is a beginning; keeping together is progress; working together is success.

Henry Ford

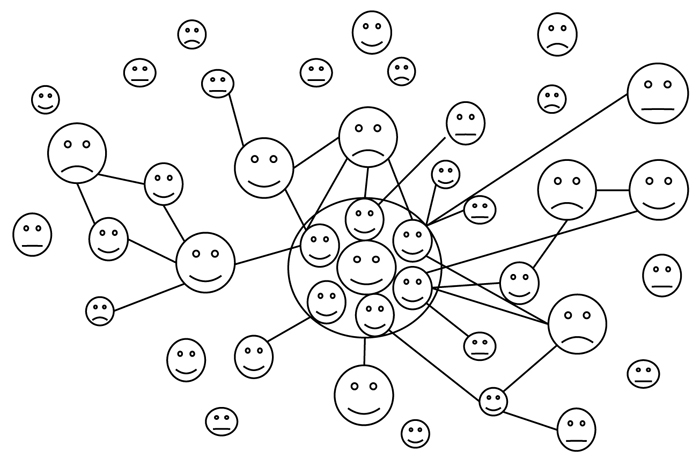

One risk affecting more projects is increased off-shoring, near-shoring and on-shoring, leading to miscommunications from different language and behavioural styles.

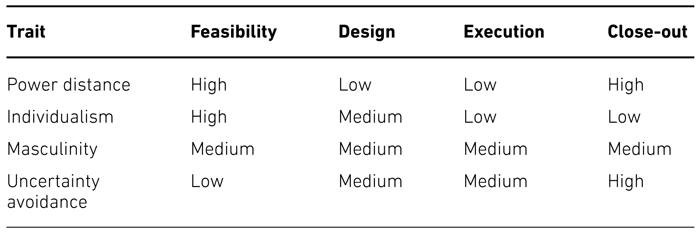

Professor Rodney Turner reviewed data on the abilities of different cultures to perform projects,17 and noted that the Western philosophy of project management did not fit with some cultures. Using some standard parameters for measuring cultural differences, he established that different cultural outlooks were more suited to different phases of the life-cycle. I like this perspective as it reinforces the fact that a diverse group, as long as they have mutual respect and work as a team, creates a stronger entity. He noted that Eastern cultural attitudes were much more suited to initiation and roll-out phases, while Western cultural attitudes were more suited to delivery phases. So, from the table in Figure 3.12, an ideal scenario might be to think like a Latin woman for the initiation stage, turn Anglo Saxon for planning and execution, then Arabic for termination. In other words, you are going to be more successful the more flexible you are.

Figure 3.12 Preferred cultural approach at different stages of the project life-cycle

In her book on the power of the introvert, after pointing out that a cult of the extrovert has ingrained its way into Western societies in recent decades, Susan Cain points out that the role of the quiet, introverted expert is still well respected in Eastern cultures.18

We should not pre-judge individuals by their cultural stereotype, but if we treat cultural differences as if they were not there, we will end up disappointed at best. With the growing reliance on multi-country and multi-cultural delivery, I am being asked to facilitate workshops helping teams to work better together, a kind of ‘project kick-off +’ workshop, though they have usually already attempted to kick off and re-started when difficulties have emerged.

I was called in to one global company, which was Indian owned but with headquarters in London and operations in the Americas. The newly appointed global head of projects had been asked by the new CEO, both from England, to consolidate all project groups and activities across all project types across all countries to create a portfolio management capability. The problem was, people just did not seem to want to do what they were asked and started to become entrenched in whose fault it was. People did not turn up on time for meetings, reports were not submitted, processes were not followed, and so on. This was taken as evidence of unprofessional conduct.

The opportunity was created to get representation from each of the regions in the same room. To me, it seemed evident that the problems arose from a lack of appreciation of the different maps of the world, or even lack of appreciation that there were different maps of the world. Since we were in effect initiating a change program, I took the opportunity to get them to co-create a team charter. The organisation actually had a very good set of corporate values which everyone could buy into. Differences soon surfaced, however, on the behaviours behind those values. The action of one, with good intent, might be taken as a slight by another. Showing respect by remaining with the person you were talking to was disrespect to the person you were late for. Sending report templates to help standardise could be interpreted as undermining trust in ability. Centralisation of process might hamper the way you got things done in another country. Any of this sound familiar yet? As time to get results was short, I facilitated a process of finding accommodations. Having emphasised the source of conflict and the desire to be better together, the result was inevitable. Once everyone started to appreciate that they saw the world differently, the team started to gel.

The effort required to integrate teams can be overlooked when we are asked to migrate diverse organisations onto common platforms and systems. How can you start to resolve differences in your team and find accommodations?

Think about where your preference lies, then think about where that of other parties might be. Better, why not do it together. The simple act of exploring it, working together and appreciating difference will work magic. Better still, put a motivating frame around it such as: ‘In order to work even better together, would you like to explore our different behavioural preferences and how we might make a stronger team?’ How would that make you feel?

The art of leadership is saying no, not saying yes. It is very easy to say yes.

Tony Blair

I was speaking to the head of delivery of an international telecoms company recently who was saying that he was having trouble trusting the on-shoring team because, although they always agreed, sometimes they did not deliver.

It reminded me of when I was working in the nuclear industry, back in the days when most people did not travel much, and our biggest clients were Japanese utilities. I was being considered as the new head of the Japanese office and was speaking to some of the people who had progressed through that office. One of them, who went on to be head of site, advised me, when in Japan, never to ask a question for which the answer might be ‘no’. He related the story of when he was in a restaurant there and ordered a specific fish. After a long time waiting, their guide advised him to order something else. Of course, staff had already made subtle hints, but too subtle for his Western ear. As explained to him after the event, they probably felt that they would have lost face by telling him that they did not have what he wanted. I think the world has moved on since, but loss of face remains a big factor in many cultures. He explained how it became a subtle art, like solving a riddle, as to how to infer a ‘no’ without getting them to say it (for example, ‘would you recommend this fish today or a different one?’).

Compare ‘Will this be ready by tomorrow?’, with ‘Given your expertise and experience, when could we guarantee this will be ready?’ Which question type is likely to give the most reliable answer?

Do you think there are different shades of ‘yes’? Usually, I am sure that when you say ‘yes’ you fully intend to deliver on your promise. Sometimes, perhaps out of a work context, have you ever said ‘yes’ while perhaps not being fully committed? How about imagining shades of ‘yes’ from:

Yes, absolutely – I will do my best – I will try – if I can make time – I will add it to my list – yes, I hear you – yes, please go away and bother someone else – NO!

Knowing this, how might you tell which yes you are getting?

We run this as an exercise in workshops where you think of how you might say ‘yes (definitely), yes (maybe) or yes (not likely)’ and your partner has to guess which one you are saying. How successful do you think you can be when you really focus on listening to the other person instead of assuming the answer you want?

3.6.3 Cultures within organisations

Preservation of one’s own culture does not require contempt or disrespect for other cultures.

Cesar Chavez, civil rights activist

Of course, we do not have to cross national boundaries to find different cultures. Cultures vary across sectors, organisations and functional groups. How different do you think the cultures of departments for finance, HR, marketing and IT might be? Do we ever implement projects across these boundaries? Of course we do, but how do we go about encompassing these different cultures in our communications?

The first stage is to recognise that, without crossing international borders, we are entering a different cultural group and should modify our language and behaviour to get quicker and easier engagement.19 The approach remains constant in becoming inquisitive as to their map of the world and how it differs from ours and then tailoring our message to it. Using the techniques described for developing rapport quickly in Section 3.20, especially looking for common ground, is an essential preface to get off on the right foot.

What makes up our maps of the world? Aside from differences in our meta-programs and our preferred representational systems, our values and beliefs really shape how we react to things. If you trespass on someone’s belief system, then they are likely to get emotionally involved. How do you find out about people’s maps of the world quickly?

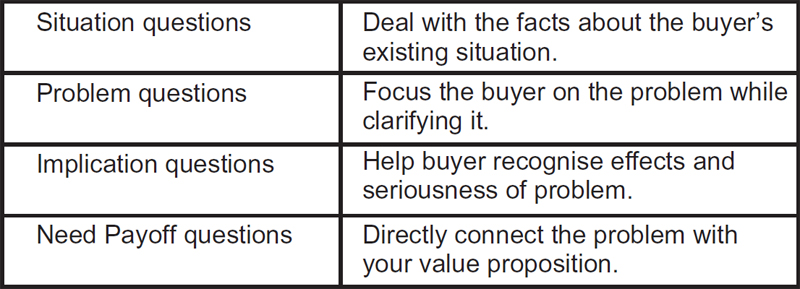

Prior to the days of Wikipedia, a colleague from my executive MBA worked as a salesman for Encyclopaedia Britannica. I asked him his top tips for sales and he confided in me that he used a lot of NLP, not to influence but to understand. He said he gave himself 30 seconds to understand the potential buyer’s map of the world before deciding whether to walk away or commit to make the sale. Specifically, if education and their children did not seem important to the prospective buyer, and they had no aspiration for their children to progress to university, then he would decide to quickly move on to his next prospect. Lesser skilled colleagues would waste potentially productive time hanging in to try to close a sale. (He is now a director at a head-hunting firm placing CIOs.)

You do not have months or years to work out your stakeholders’ maps of the world as you might in operations, but you do have a lot longer than 30 seconds. How might you go about it? What kind of questions are you going to ask? How about some questions like these:

- What is it you value about the work of your department?

- How do you believe this process/system/project might help you?

- What is it specifically that you are interested in?

- Is there anything we could do to help you to create more value?

- How would you like us to involve you?

- How would you like us to keep you informed?

- Will you help us to spread the word to your colleagues?

- Is there anything else we should know?

If you were asked these questions by someone who had already established some measure of rapport with you, how would it make you feel? That you were involved? That they were trying to be helpful? Would you be tempted to contribute in some way?

3.6.4 Co-creating a team charter to help bridge the cultural abyss

The best way to predict the future is to create it.

Peter Drucker, management guru

Co-construction of a team charter is an excellent way to get any initiative off to a great start.20 I have seen very wordy documented team charters, but I much prefer something created in real time using mind-mapping software or even whiteboard/flip charts.

I focus on getting participation and buy-in. Ask questions which help to reveal differences in world-views to make this apparent to all parties so that they realise we are looking for understanding and accommodation, not a set of house rules. I ask questions such as:

- How do you feel if someone doesn’t remember your name?

- How do you feel if someone is late for a meeting with you, or forgets?

- How do you feel when someone doesn’t supply you with information when they promised?

- How do you feel when you can’t seem to get sign-off?

- How do you feel when your team members turn in shoddy work?

- What do you like most about working on projects and in teams?

- What things annoy you most when working in teams and projects?

Notice, I ask a lot of questions based on ‘how do you feel...’ as no one can argue with the way you feel.

I’ve learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.

Maya Angelou, international human rights activist and author

I am looking to construct, in some form or another, information similar to that captured in the table at Figure 3.13. But the content is not important once it is written down; the most important thing is to co-create it in order to get buy-in. Better, if you get a physical copy in draft during the meeting, even if on a flip chart or whiteboard, and each person commits to physically signing up to it. It is your contract and understanding as to how you want to work better together. This approach has been very successful in co-creating a joint team from different partnering organisations to help resolve different organisational drivers from parent organisations.

Figure 3.13 A simple team charter

|

|

Our brand and identity statement: |

‘We are…’ |

Common values |

Behaviours we expect to observe supporting those values |

Value 1 |

Behaviour x |

Behaviour y |

|

Value 2 |

Plan |

Value 3 |

Do you see the value in co-creating a team charter? Do you have a team charter? Do you want one?

3.7 FLEXIBLE APPROACH TO TIME – HOW TO BALANCE BEING ON TIME AND ‘IN THE MOMENT’

How does a project get to be a year behind schedule? One day at a time.

Anne Wilson Schaef, The New York Times bestselling author

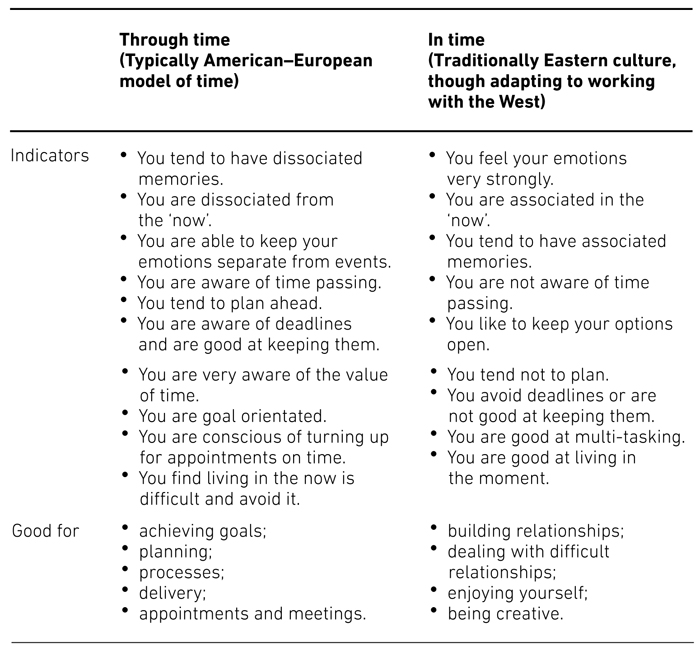

Have you ever noticed how some people always seem to be behind the clock, constantly rushing, often late, while others seem to cruise through life? Have you noticed that some people get reports in on time while others have to be chased? Some people produce a schedule, while others are reluctant to even rough a plan, let alone work to one? On the other hand, which are the people that you would pick to engage a difficult stakeholder, or speak to the unions about a change program? Maybe some of the same people who do not plan?

The essential skill for time management is to be able to assume a ‘through time’ position. The irony of many time management courses is that they are written by ‘through time’ people for ‘through time’ people. They make little sense to people who are predominantly ‘in time’, yet they are the ones who really need time management tools. (If operating ‘through time’, you are mismatching people who are ‘in time’, out of rapport and so the communication is likely to fail anyway.)

In this section we will look at our natural orientation to time and practise techniques for changing orientation to context.

Timelines were briefly introduced in Section 2.16. The NLP meta-program for time helps us to determine which groups people naturally fall into (see Figure 3.14). Like all meta-programs, however, note that they are context-based, so you may behave differently in work situations than in leisure situations. If so, all the better, as you have a good basis for flexibility.

Exercise 3.6 Determining your timeline

- Close your eyes and imagine a line containing your past and your future.

- Does the line pass through you or not?

- Is your past behind you or not?

For through time:

- Timeline lies outside your body.

- Often the past is to your left and the future to the right.

In time:

- Timeline passes through your body

- Often the future is in front of you and past behind.

Which type are you?

Figure 3.14 Different timelines

3.7.2 How to be in time, on time

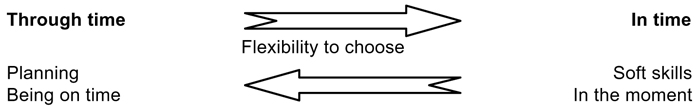

So, now you know what your normal timeline is. Rather than just give you an excuse for not planning, or not being good at one-on-one situations, the main purpose of NLP is to develop flexibility. Wouldn’t it be good to choose which timeline you are operating on depending on the task? Well, you can change your timeline because you created it in the first place and can recreate it if you choose.

You can change the orientation of your timeline so that you can experience a different mindset without changing any of the individual memories and events that your timeline is made up of (see Figure 3.15).

I personally found these exercises very useful, but was taken aback by the widespread sharing of techniques to be ‘in time’, that is, ‘in the moment’, more of the time. Maybe it is something about the world we choose to live in, or its impact on our lives outside work.

Figure 3.15 Choosing timelines

Exercise 3.7 Changing your timeline

If you are a goal-oriented person who generally operates through time, but you want to operate in time for a delicate meeting, you can, with practice.

- Close your eyes and imagine your timeline. For through time, this will generally be in front of you running left to right (or vice versa).

- Now step on to the timeline.

- Give yourself a minute to adjust as it can be disorientating, especially as you become more practiced at the switch.

- How does that feel? You may feel more grounded, more in the moment.

- Turn your head so that it faces your future. Imagine your future.

- Now rotate your head so that your timeline is running from your future, through your body, to your past.

- Take a moment to reorient.

- Immerse yourself in your planned task and let time slip away. (I like to imagine a clock melting away like a Dali painting while I am doing this.)

- Now open your eyes.

Conversely, if you are generally an ‘in time’ person but you have a deadline to meet, you may wish to choose to operate ‘through time’ for a period.

- Close your eyes and imagine your timeline. For in time this will generally be running through your body.

- Now step to the side, off your timeline.

- Give yourself a minute to adjust as it can be disorientating, especially as you become more practiced at the switch.

- You may feel a little more objective, a little more able to take an overview.

- Turn your head to look up and down your timeline, which will now be in front of you. You are now observing time and have control over it.

- Imagine your task superimposed along this timeline, with key activities laid out in the correct order.

- Feel your internal clock running like your own metronome.

- Now open your eyes and let your internal clock guide you through the day. As you go through your day, think about the most appropriate way to be operating with regards to time according to what you are trying to achieve. Practise the technique and the changes will move from subtle to dramatic. Being in time or through time is a choice, not who you are.

3.7.3 Gaining rapport through matching timelines

Have you realised yet how much easier it would be to gain rapport and understanding with other people if you could match their timeline? It is difficult to explain to someone who is ‘in time’ while being ‘through time’, and vice versa. Some of the give-aways for which timeline people generally operate in are shown in Figure 3.14. You can find out a lot about how people think about time, together with their critical sub-modalities, by listening to their language, for example:

- It was in the dim and distant past.

- He has a bright future.

- I am looking forward to a holiday.

- Put the affair behind you.

- Time is running out.

- Time is on my side.

Think of one of your key stakeholders. Recall how they behave and what they say. Do you think that they operate in time or through time? How could you check? What might you do before your next meeting?

3.7.4 Use of future pacing and ‘as if’ reframes to aid problem solving

In several of the exercises in this book you will see the final stage being to ‘future pace’, that is to imagine yourself in the problem situation in the future and imagine how you would react with the clarity and changes of mindset from the exercise. This is similar to one of the exercises on reframing, where we act ‘as if’ something has already happened, then test our reaction while looking on it with a different mindset. The advantage of going to a future state is that it dissociates the individual from difficult situations. Just as we can have 20:20 hindsight, it also allows people to move past obstacles that they cannot resolve when the obstacles are in front of them.

Things work out best for those who make the best of how things work out.

Zig Ziglar

Exercise 3.8 Future pacing

- Imagine a problem/obstacle preventing project completion.

- Now imagine you have successfully finished the project and are at the lessons learned/celebration meeting.

- Looking back:

- How did you solve it?

- Who helped you?

- What was the critical step?

- What was the one thing that you had to do to move forward?

Conversely, verb tenses can be used for putting a problem into the past, for example: ‘That has been a problem, wasn’t it.’ Note that the grammar is purposely mixed to confuse the conscious brain so that the instruction to put things in the past can speak directly to the subconscious. A slight change of emphasis also acts as instruction.

3.8 PLANNING FOR SUCCESS – LOOKING BACK FROM THE FUTURE USING PRE-MORTEM

Tomorrow belongs to those who prepare for it today.

Malcolm X

Too many projects fail, but most of these can be avoided by a simply using a pre-mortem, adopting the NLP concept of future pacing.

As a ‘Gateway Reviewer’ for mega-projects and high risk projects across the UK plc estate, as well as spending a lot of time on intervention and turnaround, I see more than my fair share of project failure. Often I am surprised that the high failure rates which are widely reported are not even higher. The saddest part for me is that the reasons for failure were probably knowable and avoidable from the outset.

We know why projects fail; we know how to prevent their failure; so why do they still fail?

Cobb’s Paradox

This means that when projects do fail, sacrificial lambs are easy to find. When your project has failed, you will probably do a post-mortem to find out what went wrong anyway, so why not do it up-front instead and either save your resources by not starting or manage-out the risks that might knock your train off the rails?

How can we implement the lessons learned before we start the project? In the NLP world we often use the technique called ‘future pacing’ to get our clients to imagine themselves in the future, both to mentally rehearse going through the steps to get there and also to look backwards to help the imagination create insights about what must be done to get them there. Imagining we are in the future beyond the problem helps to set our thinking free and unleash our imagination.

Exercise 3.9 Carrying out a pre-mortem

Set time aside. You can do this exercise quite quickly, but half a day to avoid failure is a good investment. Think of a venue, ideally away from the work environment as you want people to speak freely and be unconstrained (as you read in Part 2, physical locations like the workplace anchor behaviours).

Pick people. Between 6 and 12 is a good number to get enough ideas without losing contributions from the quieter ones in the group. You will want a range of perspectives and thinking styles in the room. Now would be a good time to get your client/end user in the room. Also get your critics and ‘black hats’21 in the room. Maybe you should even consider inviting Cassandra.22

If you do not have a good facilitator, then bring one in – the project and people’s time are valuable, so do not waste them in order to save a tiny fraction of a per cent of the project value. A good insurance policy is worth the investment.

Tell people why they are here: to help the project to succeed, and success is thinking about as many ways as possible of why the project might fail. Or, rather, to work out, from a future perspective, why the project might fail.

Set the stage – people are most creative when they are having fun, so why not get into the spirit and play-act a little. (How would a ‘who dunnit’ murder mystery, or even a funeral ‘wake’, where people reminisce about the dear departed, stimulate the creative process?)

I use ‘spatial anchors’ to separate out the present and the future in different locations on the floor. In the future spot it is useful to have a flip chart to record ideas, and when we come back to the present we will have another flip chart making action plans for the present.

Initially, I use some Milton language and deliberately confuse timelines to improve chances of side-lining people’s conscious minds and assisting creative thinking. Something like, ‘Are you curious as to why, in the future, we will look back to when the project was to be implemented; and think about what we could be doing now; and wonder what people will say about why the project failed; and do those things now that will help future success’ (no question mark, i.e. no inflection in voice).

Now I play-act a short story to get us from the present to a safe distance in the future. ‘We are here today [standing on spatial anchor for the present] to have some fun, by imagining [while walking slowly across to spatial anchor for the future] that we have miraculously been transported to the future, at the company’s expense, business class, to look back on our project. And moving forward [while walking], through requirements, specification, design, build, test and roll-out. But the project failed [pause at half way mark]. But five years beyond that, when we have moved on to other successful projects, and maybe met up again like this [now on the future anchor], and look back at today [looking across at present anchor], what are the things, with the benefit of hindsight, that might have been the cause of failure. Shall we see if we can work it out between us?’

Pick someone out to start who is likely to make a good contribution to get things started. We are in brainstorm23 mode, so do not allow filtering or critique of people’s contributions. Use your facilitator’s skills to draw out reasons from everyone, especially those who might usually be quiet or reserved. Conclude with, ‘So, is our reason for failure in that list, or are we still missing something? And if we were missing something, what might it be?’

Now we return to the present. ‘So, coming back to today, here in this room, now [while walking to the anchor spot for the present]. Looking at that list, given to us with the benefit of 20:20 hindsight, is that a good list, does it contain that gold nugget that will save our project?’ Take confirmation, or recycle back to the future anchor and extract additional learnings.

Next we deal with each of the un-filtered ideas on the flip chart and quickly filter them for likely probability and impact, as we would do in a traditional risk workshop. From the refined list, we can then task pairs or groups to work up initial ideas for mitigation plans for remaining items. If time is short, this can be done by a sub-group after the event.

Bring the session to an end by thanking everyone for their input and creativity and pledge to work up the outputs to improve the risk register.

If you have found the thing that everyone knew but no one wanted to talk about, the elephant in the room, or some other nugget, then you will have saved everyone from a lot of wasted effort and maybe saved your project. Wasn’t that much better than waiting a while to present at the project autopsy?

If there was nothing new, then you have done a fantastic job at project assurance, done an excellent job at stakeholder engagement with your client, and carried out a first class team-building event– well done!

The process of ‘future pacing’ helps us to gain emotional distance to speak freely. If you are new to this game it may sound fanciful, but the results are well researched by Daniel Kahneman.24 If you are not yet brave enough to try it out, you can start with a tame version from the Harvard Business Review25 based on research at the University of Colorado in the late 1980s.

When working in the automotive industry we carried out an engineering technique with some similarities called Failure Mode Effects Analysis (FMEA), where you predict what symptoms a failed component might display, once built and in operation, and then work backwards to identify candidates for the root cause. From there you go into re-design, and work out tests to identify and eliminate root causes should symptoms manifest in operation.

A fellow author related to me a second hand story about a similar kind of workshop for Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic project. I have to admire a man for whom the epithet, ‘The sky is the limit’ is not empowering but a limiting belief! For him it was a window to an opportunity for a new line of business. What could go wrong?

Well, his team did not find it difficult to come up with a few potential showstoppers: they did not have a space plane, if they built one it might blow up, they might not get a licence to fly a commercial plane in space, they did not have a space port, no customers, no money … ‘Enough,’ he cried, counting the risks and issues and the number of people around the table. ‘Right, you [pointing], sort the funding out, you get me a space port, you build me a space plane, you make sure it doesn’t blow up, you get it licenced … Well that was easy.’ I saw their program manager present at APM’s annual conference in 2011; they had funding, customers, a futuristic spaceport in New Mexico, and a space plane which hadn’t blown up when I first wrote this as a blog.26 (OK, so the project is really behind and the customers have not flown yet, but they still seem happy, because their imagination bought into a story.)

Do you or your sponsor or any of the other senior stakeholders have an uneasy feeling about any of your projects?

I was invited to give a talk to a large community of practice and spoke on the topic of a forthcoming book, How to Make all Your Projects Succeed.27 I had trained many of the people in the room, so was intent on ‘walking the talk’ and demonstrating some of the NLP tools and techniques on public speaking, presenting yourself and use of stories and metaphors, so I was actually training while talking. For emphasis, I focused on five topics. Afterwards, one of the earlier speakers, who had presented lessons learned on a major project failure, confided to me, ‘I spotted four of the five reasons in my feedback report.’ I had spotted all five while the project was still alive, so it was little surprise to most people that the project failed.

Would it be useful to give yourself and your sponsor assurance through a technique like this? So that you can honestly say after the event, ‘it was not foreseeable’?

There are known knowns. These are the things that we know that we know. There are known unknowns. That is to say, there are things that we know we don’t know. But there are also unknown unknowns. There are things that we do not know we do not know.

Donald Rumsfeld, former US Secretary of Defence

3.9 DEVELOPING FLEXIBILITY IN LEADERSHIP STYLE

There is nothing more difficult to take in hand, more perilous to conduct, or more uncertain in its success, than to take the lead in the introduction of a new order of things.

Niccolo Machiavelli

‘Leadership and influencing’ is one of the three core skills assessed for the ‘Expert BA’ qualification. Leadership invariably comes up when I ask audiences for the key behavioural competencies. But that label means different things to different people, in different cultures, and indeed morphs over time. Historically, in most cultures leaders were born into position, and in the past our military officers could only gain that rank through birthright rather than ability or experience. Note how such world-views have moved on in the light of overwhelming experience over the last century. Now, it is widely appreciated, and readily measured, that high scores for EI make for better leaders as well as all round better performers.

3.9.1 The rise of emotional intelligence in leadership

I think for leadership positions, emotional intelligence is more important than cognitive intelligence. People with emotional intelligence usually have a lot of cognitive intelligence, but that’s not always true the other way around.

John Mackey

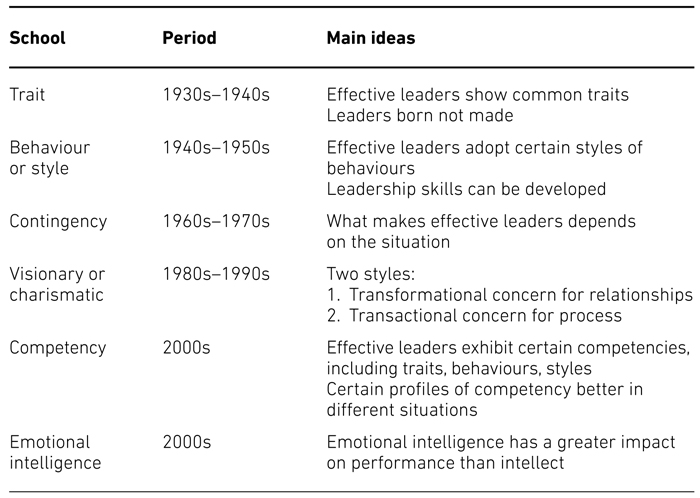

Figure 3.16 Schools of leadership

Professor Rodney Turner observes that there is little work setting leadership in projects within the context of the emotional intelligence school, but there is a significant relationship between project success and inner confidence and self-belief.28 The latter element is what NLP refers to as the self-reference meta-program (as against the opposite, external reference). Note that self-reference tends to make people more resilient, though less open to feedback.

Turner also observes that, while some say leaders are born not made, and some people are naturally more suited to leadership than others, everyone can improve their leadership skills.

My hope was that organizations would start including this range of skills in their training programs – in other words, offer an adult education in social and emotional intelligence.

Daniel Goleman

3.9.2 Six styles of leadership

As we look ahead into the next century, leaders will be those who empower others.

Bill Gates

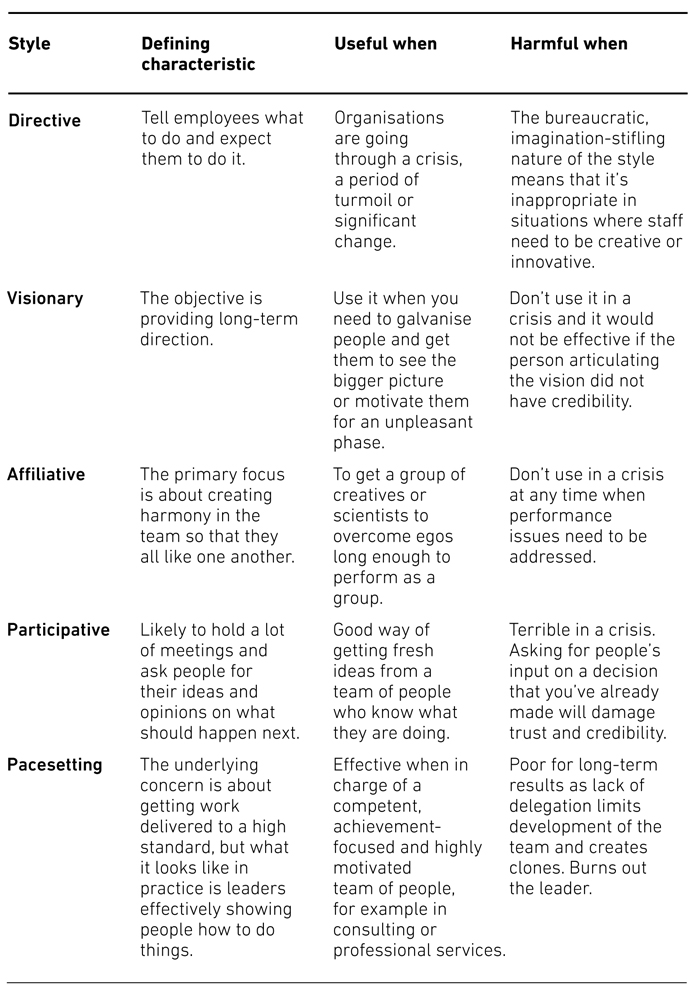

Turner wrote a comprehensive series on leadership in the project context based on research as to whether different leadership styles influenced project success, and whether different leadership styles were more appropriate to different types of project.29 There is no right or wrong style, only the wrong context. I think each of these styles has use for some types of project in some situation or other. What is your preferred style?

Figure 3.17 Six styles of leadership

Source: Compiled from leader articles in The Sunday Times, January–March 2008.

Reflecting on the past, do you think you have flexed your style to situations and been as effective as you could be? What style do you think works best in an agile environment? Looking to the future, can you think of a situation where you might want to flex your style?

At times in my career my strategy was so forceful and aggressive that I effectively bludgeoned dissenters and got my own way without taking any prisoners (including the client on some occasions). This might kindly be referred to as an extreme instance of the ‘directive’ style of leadership. The directive style can be useful in turnaround situations and projects where there is no clear plan and lack of direction. When I moved on to change management projects, however, I quickly realised that this approach was not achieving desired outcomes. I had to learn to do things more elegantly; that is, develop more flexibility in style and approach. If we do not adapt our style to the situation, aside from achieving limited success, we are liable to suffer excess strain and burn-out.

Reflecting back, I can see a progression in my career from a pure directive style, through pacesetting to be more facilitating. I now focus on spending more of my time in a coaching style. Of course, that is my own opinion. In a survey by the CMI Institute, most managers said that they used a coaching style, yet replied that their managers used a directive style. Perhaps CMI members are truly different, but perception obviously comes into it. There is in fact no best style of leadership, as it should be contextual. So, how do you plan to become more agile in your leadership style?

3.9.3 Supervising, managing or leading – what got you here might not get you there

Leaders are people who do the right thing; managers are people who do things right.

Warren Bennis, leadership guru

I was in the headquarters of a professional body when someone asked the question in relation to an application for chartered status, ‘Can I put my time as a supervisor down under leadership experience?’ ‘Yes’, came the reply. I disagree; though both have a part to play, leading and supervising are poles apart. If someone is not sure what they are doing and does not know how to do it, then we might have to give them detailed instructions if we are short of time in order to meet a deadline. Ideally, we would have sufficient time to bring them up to speed and coach them to an acceptable standard.

When I started my career, I was informed about ‘The Peter Principle’,30 which says that people are promoted to a level at which they become incompetent, and then they do not rise any more. Years later, Marshal Goldsmith, probably the most influential executive coach in the Western hemisphere, penned the bestseller, What Got You Here Won’t Get You There.31 Basically, you need to stop doing some of the behaviours that served you in the past in order to adopt those which will serve you in the future.

This reminds me of a story I was told on my slow path towards enlightenment in martial arts. A novice in a Shaolin Buddhist temple, perhaps Kwai Chang Cain himself, goes to have tea with the wise old monk (a man as bald and eminent as Marshal Goldsmith himself). The novice holds out his cup for tea. The monk delicately pours tea, and continues to pour. Eventually, still holding a serene smile that only an enlightened one can, the monk pours until the cup overflows. The novice, at first reluctant to interrupt the monk, now says, ‘Master, there is no room in the cup for more tea!’ To which the master replies, ‘So student, how will you empty your cup to receive the new knowledge that you seek?’

Exercise 3.10 Progressing from supervising to leading

- Look at the mix of words below

checking quality describing tasks listing activities describing a vision disciplining staff coaching managing your state managing stakeholders using stories and metaphors

- Where do you think these fit along the path from supervising to leading?

- On that continuum, where do you see yourself now?

- Where do you think others see you?

- Where do you see yourself in the future?

- Before you take on those new behaviours ahead of you, what behaviours which served you in the past might it be worth doing less of in order to practice more of the behaviours which will serve you in the future?

- When will you start on your future path and let go of what got you here?

Your attitude determines your altitude.

Zig Ziegler

During training courses, we do a kinaesthetic version of this exercise where we get delegates to write words associated with supervising, managing and leading and place them on a continuum on the floor. We then walk along this timeline to where they think others see them, envisioning letting go of some of the behaviours behind them in order to focus on the behaviours in front of them. The effects have proven to be profound. Why do you think it works?

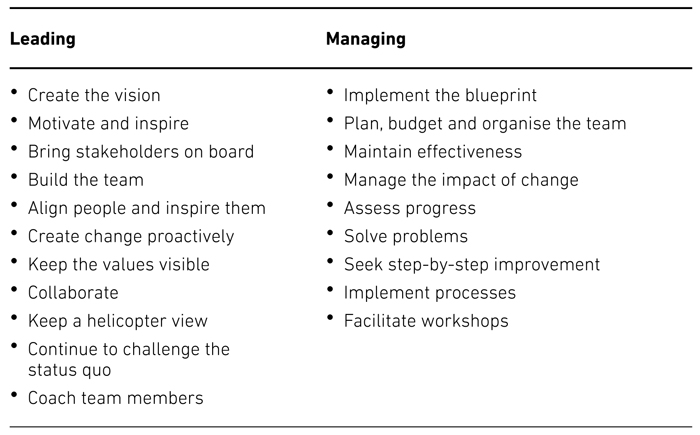

So, should a BA/change manager be a manager or a leader? I think an effective change manager requires awareness of the context in order to flex between managing and leading depending on the activity being undertaken. Does the table in Figure 3.18 reflect your map of the world?

How can you spend more time on leading change?

Figure 3.18 Change managers need to be both managers and leaders depending on context