CHAPTER THREE

NEED FOR THE SIX SIGMA BUSINESS SCORECARD

A recent business assessment survey [developed by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST)] and conducted by Quality Technology Company led to some interesting findings about business performance. Most respondents reported that they have no idea how company leadership planned to improve the profitability. Only a few people knew how successfully their department was in achieving business objectives.

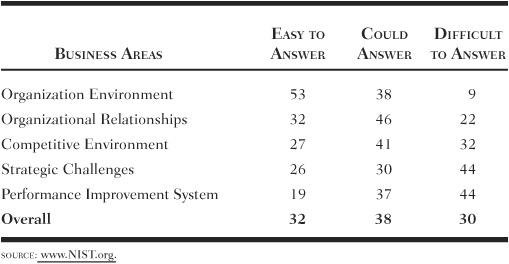

The respondents in the survey represented owners, managers, engineers, and operators of several companies (including those in the Fortune 100). The responses of employees to questions in various business areas are summarized in Table 3-1.

TABLE 3-1. Business Assessment Survey Findings

As is apparent from this table, only about one-third of the employees can easily answer questions about business performance, implying that information about the business performance is not readily available to employees.

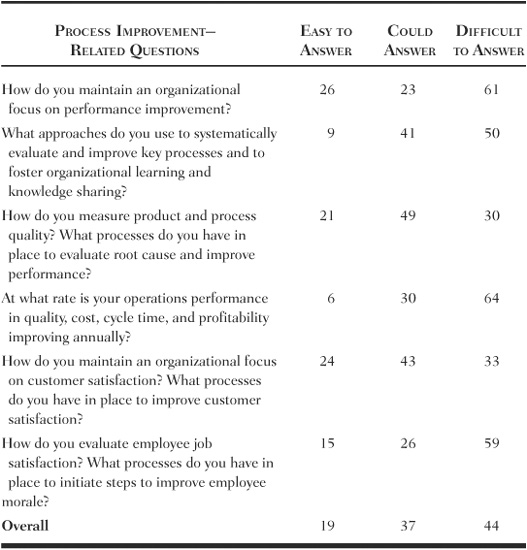

Interestingly, the consistency of responses among the sections was quite surprising. The two weakest areas are the strategic challenges and the performance improvement system. In the case of the process improvement system, only about 20 percent could easily answer any questions. (See Table 3-2 for details on the process improvement area.)

TABLE 3-2. Response to Process Improvement–Related Questions

MISSING RATE OF IMPROVEMENT

The most significant finding is that people are unaware of the rate of improvement in their companies. They are also unaware of their process for improvement, implying that the focus is on delivery, not on getting better. In addition to reporting being unaware of process improvement, most respondents indicate that mechanisms to assess employee satisfaction are very sparse. Only 15 percent of people could easily answer questions about their company’s process for improving employee satisfaction. Considering that employees’ input is critical to the leadership, for generating new ideas as well as for getting feedback about the performance of the company leadership, this finding is troubling. As for the competitive position of the company, only a few employees know about their competitors and their competitive advantages. This lack of awareness can limit a company’s improvement.

Employees are very familiar with their customers, as well as what their customers want. At least they think so! In the current business environment, the supply chain relationship plays a critical role in the success of a company; employees, however, have limited interaction with their suppliers. Supplier relationships have become very important as businesses become increasingly dependent on their suppliers.

These employees know what they are supposed to do, but they have a difficult time figuring out how well they are doing. Whether they are in engineering, sales, purchasing, production, quality, or another department, they do not have measures of performance for the various aspects of their jobs. They believe that their company has measurements for the short term but does not care about long-term performance. They have measurements about the function of the company, but they do not have the measurements about the company’s strategic intent. Employees are unaware of the competitive position of their products and services, mission and values, and results achieved. In summary, employees feel good about their products and services; however, they are not informed of the performance levels expected or what rate of improvement they are supposed to achieve.

INSUFFICIENT PROCESS PERFORMANCE MEASUREMENTS

Most businesses have measurements for sales and profitability. They do not, however, have measurements for operational effectiveness. Every company has an accounting function, whether internal or outsourced, to summarize the accounts payable and receivable, balance sheet, and profit and loss. Many organizations, although they hope to be profitable, are penny-wise and dollar-foolish.

Some companies have established measurements that support the premise that they are profitable. This premise is quite possible in industries with a niche market, a lack of competition, good margins, and some waste that can be tolerated. However, that privilege is only for the lucky few. Most companies have stiff competition, complex products, and a complex system that does not identify opportunities to reduce waste.

A typical business today consists of buildings, equipment, employees, material, customers, and management. The organizational structure may include one or multiple facilities at one or several locations. Besides that, a business may have several parts, products, or types of services that it offers to customers.

Typically, the business is managed by making sure products are delivered to the customer in the best possible manner. The focus is on shipping the product or delivering the service as best as possible to maximize the revenue. At the end of the month, the leadership knows how much money has been made in profits or how much more credit is needed to manage the cash flow.

Inside a company, life is a little more interesting. First, the sales staff are busy selling more to earn a commission than to make margins for the company. For example, a salesperson makes a deal for $500 million and earns a commission. The company finances the sales and pays out the commission. The revenue is recorded on the books, showing sales growth. A few months later, however, the customer files for bankruptcy. The company ends up in debt for $500 million, while the salesperson already earned the bonus and recognition and moved on.

Meanwhile, design engineering is busy designing the part or the product. The product is designed to best-of-design capabilities, which are practically all imaginary and incorporating all the creative juices and genius of the design team in each product. Some prototypes are built and tested for functionality. The design works by hook or crook, and the product is released to production. Production may pilot-test a few runs to verify the design. When the product works, it is signed off for full production and shipment to the customer.

Here is where the fun begins. Purchasing is buying parts from the suppliers. Suppliers celebrate their success in making sales to the company. Production, however, is having trouble producing a good product. Sometimes the product fails due to bad parts; sometimes it is incorrectly assembled by machine operators who are tired of fighting fires. Sometimes failure is due to marginal design specifications; at other times inspection and testing did not catch enough failures. In addition, the product fails at times in the field because the company CEO told employees to ship the product at any cost in order to keep his word to his customers (even if it meant skipping some verification steps).

Now the customer returns the product. Someone receives it in the company, reviews it, and assigns credit to the customer. Someone, if any time can be found, analyzes the root cause of the problems and finds an operator who needs some counseling. Quality engineering issues a corrective action, completes the paperwork, and closes the corrective action. The customer gets a copy of the completed corrective action, accepts the response, completes paperwork, and life goes on.

In addition to this life in sales-to-service operations, other business activities are ongoing. Managers make sure the product gets out the door. The support staff expedite materials and whatever else is needed to keep the operations running. They ensure bills are paid and invoices issued, that employees are paid, and that struggling employees get help when necessary.

The most interesting personalities may be those of the owners, CEOs, or presidents. They are earning a good salary, and their companies have been having some profitable years due to favorable market conditions. They are stressed, though, because they do not understand what is going on in the real business. They ask the staff how things are going, and the staff respond, “Just fine!” They do not probe further, because they believe that is the best answer they can get. Digging any deeper might stir debate, and they want to avoid conflict with the staff, even if it means avoiding the truth.

These situations may typically occur in a privately owned and improperly staffed small business—one run by an old-style management. However, similar situations occur in divisions of large corporations as well. They happen because those in charge lack understanding of the business, fail to identify a common purpose, and cede management of the processes. As a result, each employee is trying to manage his or her time at work independently. Many inefficiencies result from conflicting priorities and questionable interests on the part of employees.

Some companies have a few performance measures in place, even fancy-looking reports and charts. However, their basic goal seems to be to produce parts as fast as possible. Keep everybody physically busy instead of allowing time to be mentally busy.

Many businesses have very few measurements; some have a lot of measurements but not necessarily the right ones; others may have extensive measurements imposed from headquarters. However, these measurements do not correlate with the business reality because of ineffective communication between leadership, management, and staff. The result is insufficient review and analysis and an improper focus on speed instead of doing the job well.

Henry Ford once said that a waste of time is much more significant than a waste of material, because the material has some salvage value, while time has none. Wasted time is a particular problem for many service industries because so much of the work they do is based on intangibles, giving them more “wiggle” room. Yet service industries face similar issues in terms of measurements and performance. The issues of learning to perform better and faster at lower cost in the service industry are identical to the ones faced by the manufacturing industry.

In larger corporations, the complexity and diversity of operations mean that the overhead to arrange a meeting costs more than the meeting itself. In one company, I asked my next-door employee to set up a meeting time, as I was new there. He gave me a date for an hour to meet but a month out. There was no sense of urgency to get the job done at this corporation, and the time spent scheduling and waiting for meetings that should take place quickly wasn’t recognized as a cost.

DEMING’S 14 POINTS*

All this discussion points to the conclusion that something is missing in our businesses. Deming, who was credited with jump-starting Japan’s economy to its heights, identified 14 organizational transformation points several years ago:

1. Create constancy of purpose toward improvement.

2. Adopt the new philosophy.

3. Cease dependence on inspection to achieve quality.

4. End the practice of awarding business on the basis of the price tag.

5. Improve constantly and decrease costs.

6. Institute training on the job.

7. Institute leadership.

8. Drive out fear.

9. Break down barriers between departments.

10. Eliminate slogans, exhortations, and targets for the workforce.

11. Eliminate work standards (quotas) on the factory floor and management by objectives.

12. Remove barriers that rob the employees of their right to pride of workmanship.

13. Institute a vigorous program of education and self-improvement.

14. The transformation is everybody’s job.

Deming’s 14 points were well recognized in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Each point communicates a strategy that, if implemented, will transform an organization. These 14 points promote improvement through leadership and the system instead of through management by objectives. The first point about creating constancy of purpose is the most critical one. The leadership must be driven to maintain the continuity of the business in a competitive environment by creating jobs, growth, and profitability. The last point emphasizes empowering employees through their involvement in decision making and active participation from planning to performance.

If we look at all 14 points in their entirety, it appears that Deming’s approach is to create an organization that is natural in its functioning. In other words, the organization recognizes the intelligence of all employees, the uncertainties associated with people, superior leadership, performance of processes instead of people, and effective measurements. Deming believed that leadership’s role must be to care for employees, develop their skills, and achieve business objectives through employees’ total involvement. Deming’s main concern was the mobility of leadership and disruption caused by this mobility. Leadership’s lack of commitment to transforming an organization into a profitable one over the long term is a leading cause of poor performance.

MEASUREMENT CHALLENGES WITH QUALITY SYSTEMS

LIMITS OF ISO 9000

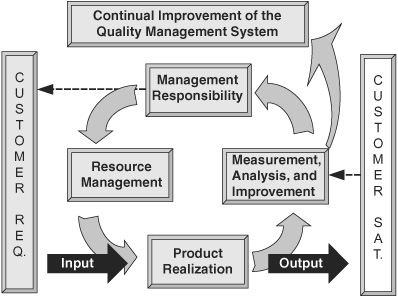

The ISO 9000 standards process model is depicted in Figure 3-1. According to the process model, any activity, or set of activities, that uses resources to transform inputs to outputs can be considered a process. For a company to effectively implement a quality management system, it needs to identify and manage various processes and their interactions. The output of one process is an input to another process. To implement a companywide quality management system, the company must implement process management at each process (function or subsystem) level.

FIGURE 3-1. Process-based quality management system. (ISO 9000:2000.)

To manage a process, the process owner needs to control inputs, in process, and output as shown in Figure 3-1. The process owner must not only understand the requirements but also be able to receive, produce, or supply according to the requirements. Verification methods are needed to ensure compliance to the requirements at various stages of the process. This might involve controlling suppliers or monitoring the product or process through data analysis, inspections, testing, or measurements. If the verification shows that requirements are not met, the process owner needs to initiate corrective action.

Once we learn how to manage a process effectively, we must identify critical process steps throughout operations, verify them, ensure that they comply with requirements, and then produce acceptable results. According to ISO 9001:2000, a process is run effectively when the process owner ensures the following: processes are clearly defined and documented, steps are clearly documented, employees are trained, good data are collected, data are analyzed, and corrective actions are taken.

If the roles and responsibilities of every employee are defined and documented and accountability is established, company management can smoothly run the business with the process management mentality. Of course, if it’s not monitored, the quality management system can be blamed for any problems. With process management, the difference between employees and management disappears. Everyone, including management, must perform the assigned tasks according to the intent and processes of quality management. With this synergy and harmony, the company develops an effective quality management system that can facilitate growth as well as downsizing equally well. A well-run quality management system should make the company perform like a well-oiled machine.

Today, about 500,000 businesses have invested heavily in the ISO 9000 system. The ISO 9000 system allows a company to create an infrastructure that guides process management throughout the organization. The most common benefits of implementing ISO 9000 quality systems include the following:

• Consistency, standardization, and repeatability of processes

• Increased business

• Customer confidence

• Better management and less confusion in the plant

There are challenges with the system, however, that have led to suboptimal performance. Some of the industrywide concerns include

• Excessive documentation or paperwork

• No change in the way of doing business

• Management ignorance

• Invisible improvement in performance

The challenges imply the lack of a performance measurement system that maintains the accountability between leadership and the operator. In other words, some roles are not played well—typically, the nonproduction roles.

SHORTCOMINGS OF SIX SIGMA MEASUREMENTS

At the same time as the ISO 9000 standards were released, the Six Sigma initiative was launched at Motorola. Some companies that have implemented Six Sigma have had difficulty sustaining the optimum level of performance. Each successful Six Sigma implementation was passionately led by the company’s chief executive. Some of the key aspects of successful Six Sigma implementation include the following:

• Commitment

• Accountability

• Aggressive goal setting

• Communication

• Common language

• Process thinking

• Innovation

• Metrics

• Rate of improvement

• Rewarding experience

To ensure that these key aspects are implemented successfully, measurements are needed to monitor progress. Typical measurements include the following:

• Defects per unit (DPU)

• Defects per million opportunities (DPMO)

• Process yields

• Customer satisfaction

• Customer returns

• Employee suggestions

It appears that Six Sigma measurements focus on performance at the process level; however, the measurements are not aggregated and correlated to corporate wellness. Corporations have found it difficult to establish a corporate sigma level that correlates with the overall corporate performance.

LIMITS OF THE BALANCED SCORECARD

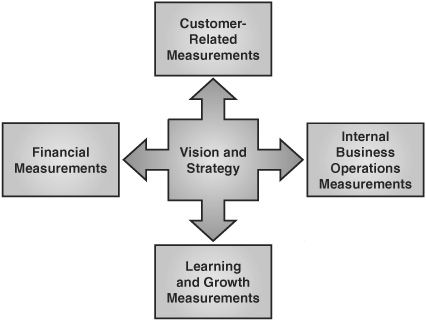

Current measurement systems tend to focus on operations, and measurements for the strategic aspects of the business are limited. This leaves leadership unable to relate to the overall performance of the business. Robert Kaplan and David Norton (1996) addressed this discrepancy when they developed the Balanced Scorecard in the early 1990s. The idea was to supplement the usual financial measures that were insufficient to manage modern organizations. Their view was that a balanced group of measurements that supports the corporate strategy would enable an organization to achieve the business objectives. A Balanced Scorecard includes measures in four areas: Financial, Customer, Internal Business Processes, and Learning and Growth, as shown in Figure 3-2. The Balanced Scorecard reveals a much broader view of what is happening in an organization than traditional financial measures alone do. This broader view, though, is only part of the value added by the Balanced Scorecard approach. The real contribution of a Balanced Scorecard program is to link the objectives in each of the four perspectives. Each organization selects specific measures and draws specific links between them.

FIGURE 3-2. Balanced Scorecard system. (Kaplan and Norton, 1996.)

The Balanced Scorecard is best deployed at the strategic level and flowed down through the organization. Work groups can devise their own Balanced Scorecards that show their contribution to the strategy of the organization. Action plans and resource allocation can be determined according to the work groups’ contributions to the corporate Balanced Scorecard objectives.

While implementing a Balanced Scorecard, managers articulate their strategy for the organization. Departments go through the training and attend sessions to develop the vision, strategy, and measurements that will lead to a Balanced Scorecard. They develop objectives and targets as well as action plans. Weaknesses in the organization can be identified through the reporting process and corrected through the learning process.

In theory, if a Balanced Scorecard is created at each department level, it could become a major measurement challenge. People who have experienced the process, however, say that by the time the Balanced Scorecard gets to work groups, the strategy has become unrelated to employees and too much effort is required to maintain the system. As with any new methods and their associated learning curves, challenges are expected.

The Balanced Scorecard has been successfully implemented at hundreds of companies; however, the remaining millions of businesses still need a practical measurement system that will enable them to improve profitability. As Kaplan and Norton state in The Strategy Focused Organization (2001), the execution of the measurement system is more important than the measurement system itself. Accordingly, fewer than 10 percent of the strategies outlined on the Business Scorecard were successfully implemented. This implies that the measurement strategy must be simplified for a successful execution.

MEASUREMENTS ACCORDING TO THE GOAL

Another classic approach, developed by Eliyahu M. Goldratt and Jeff Cox in the book The Goal (1992), appears more practical in the sense that it simplifies the main strategy for a business: to make money. The key measurements suggested in The Goal are Throughput, Inventory, and Operating Expenses. This approach stresses two main underlying beliefs: (1) Each business has many constraints, and (2) a linear approach to improving profitability sometimes leads either to localized improvement but no impact on profitability or to an adverse impact on profitability. Typically, businesses measure things such as shipments, income, speed, behaviors, work environment, physical space, overtime, efficiency, competition, market, technology, quality, scheduling, delivery, constancy of purpose, expenses (short-term and long-term), loss of good employees, sales, bottlenecks, productivity, effective meetings, R&D effectiveness, return on investment, and cash flow. These measurements tell us how various aspects of the businesses are performing; however, they do not tell us whether they are adding to the bottom line.

DEVELOPING A NEW MEASUREMENT SYSTEM

What an organization truly needs is measurements that start with its objectives and relate to processes that can be aggregated to overall performance. When this happens, measurements directly relate to profitability. In other words, the measurement system starts with a goal, it flows down to the process level, and it can be optimized. The measurement system must be able to provide a prompt and futuristic snapshot of the business’s health to the executives.

A measurement system itself should not be a major expense. The ideal system can be quickly summarized, reported, communicated, and acted upon to prevent opportunities for waste of resources, including intellect. A good measurement system promotes intellect rather than effort.

For example, a company of about 150 employees wanted to implement an improvement process to reduce waste and improve profitability. The initial attempt to develop a well-defined strategy with goals, objectives, targets, and a sound plan for execution failed. The plan was impossible to implement due to the required effort, existing culture, and skills of the employees. The company’s leadership then changed tactics. A new system was devised in which (1) each area supervisor was given a continual improvement goal, (2) a weekly review was performed, and (3) appropriate feedback was given on a green sheet or a red sheet. To our surprise, the supervisors were able to improve processes in 44 out of 52 weeks and reduce waste by about 80 percent. The company experienced its best-ever operational and financial performance.

Soon after, a new leadership team lands in the company. The leaders decide to bring their cronies and implement their own system. Soon enough, the company loses all the benefits of its previous system, loses money, and eventually closes.

Time after time, it is not the company’s processes or measurements that are the problem; rather it is that leadership is not defined as a process that should be measured for maintaining constancy of purpose, direction, and profitability. In other words, a good measurement system must include measurements for leadership as well.

Profitability is a real challenge in today’s business environment due to increased competition, reduced development time, shrinking margins, and pressures on price. To achieve increased profitability, objectives must be clearly defined and communicated, and the system must be optimized. The measurement system must provide feedback to fine-tune the system so that the business can achieve its profitability objectives— just as a guided missile that, with some statistical variation, hits its target. With the help of the right measurements and proper execution, the accuracy of the business system to hit the target must be refined for long-term sustainability.

Typically, leadership has focused on sales, finances, and the operational measurements of quality and cycle time. The more recent Balanced Scorecard measurements focus on financials, learning, internal processes, and customers—all linked to the strategic level. The Balanced Scorecard measurements, however, have not worked effectively at the operations level; thus, they are not suitable to a business’s organizational structure.

A new business scorecard system based on the knowledge gained thus far through various efforts is called for—one that not only directs the organization to achieve profitability, but also maintains profitability by ensuring a high rate of improvement in internal operations. The level of performance is not what counts; instead the rate of improvement is what matters to achieve profitability. The Six Sigma methodology, if executed as intended, achieves improvement objectives, and the Six Sigma Business Scorecard helps to achieve the intended profitability objectives.

The Six Sigma Business Scorecard combines information from the strategic, operational, and execution aspects of the business. Only through aggressive goal setting, effective data collection, analysis, reporting, communication, and improvement efforts can a business achieve the desired objectives. A Six Sigma Business Scorecard reflects the effectiveness of all processes at the action level instead of the strategic level. The Six Sigma Business Scorecard relates to the organization instead of viewing the organization from the measurements perspective.

TAKE AWAY

1. Most employees have no idea how company leadership plans to improve the profitability.

2. Most people are unaware of the rate of improvement in their companies. They are also unaware of their process for improvement, implying that the focus is on delivery, not on improvement.

3. Employees’ lack of awareness of their competitors and competitive advantages can limit a company’s rate of improvement.

4. Each employee is trying to manage his or her time at work independently with the focus to stay physically busy instead of being mentally active.

5. Fewer than 10 percent of the strategies are successfully implemented. The execution of the strategy is equally important that can be facilitated by effective performance measurements.

6. The measurement system must provide a prompt and futuristic snapshot of the business’s health to the executives. A good measurement system promotes investment rather than cost to fight fires.

7. With the help of the right measurements and proper execution, the accuracy of the business system to hit the target must be refined for sustained profitable growth.

8. The Business Scorecard coalesces the strategic, execution, and innovation aspects of the business.