Chapter 8. Subnetting IP Networks

Objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, you will be able to answer the following questions:

![]() Why is routing necessary for hosts on different subnets to be able to communicate?

Why is routing necessary for hosts on different subnets to be able to communicate?

![]() How would you calculate the number of host addresses if you were given a network and subnet mask?

How would you calculate the number of host addresses if you were given a network and subnet mask?

![]() How would you calculate the correct subnet mask to accommodate a given number of hosts?

How would you calculate the correct subnet mask to accommodate a given number of hosts?

![]() What are the benefits of Variable Length Subnet Masking (VLSM)?

What are the benefits of Variable Length Subnet Masking (VLSM)?

![]() How would you design and implement a hierarchical addressing scheme?

How would you design and implement a hierarchical addressing scheme?

![]() How are IPv6 address assignments implemented in a business network?

How are IPv6 address assignments implemented in a business network?

Key Terms

This chapter uses the following key terms. You can find the definitions in the Glossary.

Variable Length Subnet Mask (VLSM) page 385

Introduction (8.0.1.1)

Designing, implementing, and managing an effective IP addressing plan ensures that networks can operate effectively and efficiently. This is especially true as the number of host connections to a network increases. Understanding the hierarchical structure of the IP address and how to modify that hierarchy in order to more efficiently meet routing requirements is an important part of planning an IP addressing scheme.

In the original IPv4 address, there are two levels of hierarchy: a network and a host. These two levels of addressing allow for basic network groupings that facilitate in routing packets to a destination network. A router forwards packets based on the network portion of an IP address; after the network is located, the host portion of the address allows for identification of the destination device.

However, as networks grow, with many organizations adding hundreds, and even thousands, of hosts to their network, the two-level hierarchy is insufficient.

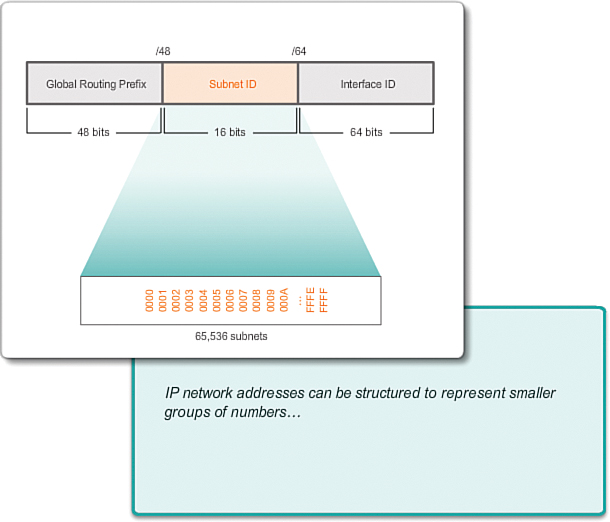

Subdividing a network adds a level to the network hierarchy, creating, in essence, three levels: a network, a subnetwork, and a host, as shown in Figure 8-1.

Introducing an additional level to the hierarchy creates additional subgroups within an IP network that facilitates faster packet delivery and added filtration, by helping to minimize “local” traffic.

This chapter examines, in detail, the creation and assignment of IP network and subnetwork addresses through the use of the subnet mask.

Class Activity 8.0.1.2: Call Me!

In this modeling activity, you are asked to think about a number you probably use every day: your telephone number. As you complete the activity, think about how your telephone number compares to strategies that network administrators might use to identify hosts for efficient data communication.

Subnetting an IPv4 Network (8.1)

One of the most important tasks that you have as a network administrator is to subnet the networks that have been assigned to you. This enables you to manage the limited IP addresses that are available to you. This section discusses the process of subnetting an IPv4 network.

Network Segmentation (8.1.1)

This section takes a look at breaking up a network into smaller networks.

Reasons for Subnetting (8.1.1.1)

In early network implementations, it was common for organizations to have all computers and other networked devices connected to a single IP network. All devices in the organization were assigned an IP address with a matching network ID. This type of configuration is known as a flat network design. In a small network, with a limited number of devices, a flat network design is not problematic. However, as the network grows, this type of configuration can create major issues.

Consider how on an Ethernet local area network (LAN), devices use broadcasts to locate needed services and devices. Recall that a broadcast is sent to all hosts on an IP network, as shown in Figure 8-2.

The Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol (DHCP) is an example of a network service that depends on broadcasts. Devices send broadcasts across the network to locate the DHCP server. On a large network, this could create a significant amount of traffic, slowing network operations. Additionally, because a broadcast is addressed to all devices, all devices must accept and process the traffic, resulting in increased device processing requirements. If a device must process a significant number of broadcasts, it could even slow device operations. For reasons such as these, larger networks must be segmented into smaller subnetworks, keeping them localized to smaller groups of devices and services.

The process of segmenting a network, by dividing it into multiple smaller network spaces, is called subnetting. These subnetworks are called subnets. Network administrators can group devices and services into subnets based on geographic location (perhaps the third floor of a building), organizational unit (perhaps the Sales department), device type (printers, servers, WAN, etc.), or any other division that makes sense for the network. Subnetting can reduce overall network traffic and improve network performance.

Note

A subnet is equivalent to a network, and these terms can be used interchangeably. Most networks are a subnet of some larger address block.

Communication Between Subnets (8.1.1.2)

A router is necessary for devices on different networks to communicate. Devices on a network use the router interface attached to their LAN as their default gateway. Traffic that is destined for a device on a remote network will be processed by the router and forwarded toward the destination. To determine if traffic is local or remote, the router uses the subnet mask.

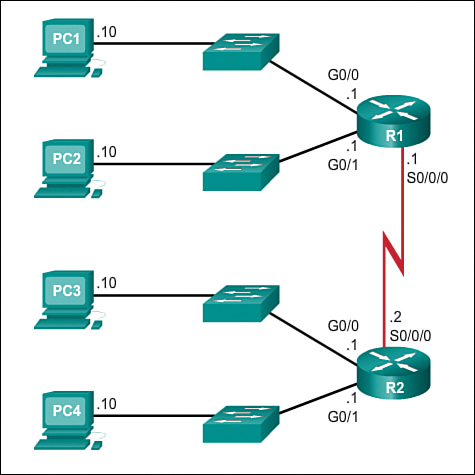

In a subnetted network space, this works exactly the same way. As shown in Figure 8-3, subnetting creates multiple logical networks from a single address block or network address. Each subnet is treated as a separate network space. Devices on the same subnet must use an address, subnet mask, and default gateway that correlate to the subnet that they are a part of.

Traffic cannot be forwarded between subnets without the use of a router. Every interface on the router must have an IPv4 host address that belongs to the network or subnet to which the router interface is connected.

Subnetting an IPv4 Network (8.1.2)

This section provides additional information on how to address the segmented networks.

Basic Subnetting (8.1.2.1)

Every network address has a valid range of host addresses. All devices attached to the same network will have an IPv4 host address for that network and a common subnet mask or network prefix. The prefix and the subnet mask are different ways of representing the same thing—the network portion of an address.

IPv4 subnets are created by using one or more of the host bits as network bits. This is done by extending the mask to borrow some of the bits from the host portion of the address to create additional network bits. The more host bits borrowed, the more subnets that can be defined. For each bit borrowed, the number of subnetworks available is doubled. For example, if 1 bit is borrowed, two subnets are created; if 2 bits are borrowed, four subnets are created; if 3 bits are borrowed, eight subnets are created; and so on. However, with each bit borrowed, fewer host addresses are available per subnet.

Bits can only be borrowed from the host portion of the address. The network portion of the address is allocated by the service provider and cannot be changed.

Note

In the examples in the figures, only the last octet is shown in binary; other octets are shown in numerical format because only bits from the host portion can be borrowed.

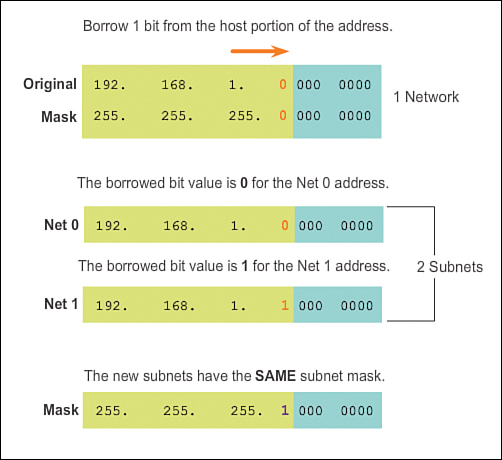

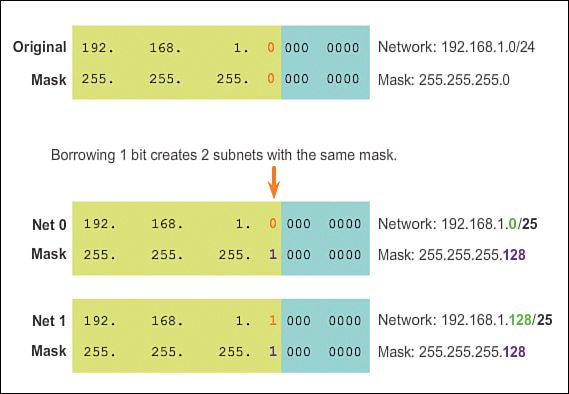

As shown in Figure 8-4, the 192.168.1.0/24 network has 24 bits in the network portion and 8 bits in the host portion, which is indicated with the subnet mask 255.255.255.0 or /24 notation. With no subnetting, this network supports a single LAN interface. If an additional LAN is needed, the network would need to be subnetted.

In Figure 8-5, 1 bit is borrowed from the most significant bit (leftmost bit) in the host portion, thus extending the network portion to 25 bits. This creates two subnets, identified by using a 0 in the borrowed bit for the first network and a 1 in the borrowed bit for the second network. The subnet mask for both networks uses a 1 in the borrowed bit position to indicate that this bit is now part of the network portion.

As shown in Figure 8-6, when we convert the binary octet to decimal we see that the first subnet address is 192.168.1.0 and the second subnet address is 192.168.1.128. Because a bit has been borrowed, the subnet mask for each subnet is 255.255.255.128 or /25.

Subnets in Use (8.1.2.2)

In the previous example, the 192.168.1.0/24 network was subnetted to create two subnets:

192.168.1.0/25

192.168.1.128/25

In Figure 8-7, notice that router R1 has two LAN segments attached to its GigabitEthernet interfaces. The subnets will be used for the segments attached to these interfaces. To serve as the gateway for devices on the LAN, each of the router interfaces must be assigned an IP address within the range of valid addresses for the assigned subnet. It is common practice to use the first or last available address in a network range for the router interface address.

The first subnet, 192.168.1.0/25, is used for the network attached to GigabitEthernet 0/0, and the second subnet, 192.168.1.128/25, is used for the network attached to GigabitEthernet 0/1. To assign an IP address for each of these interfaces, it is necessary to determine the range of valid IP addresses for each subnet.

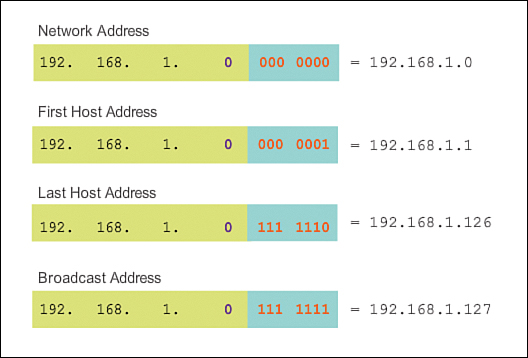

The following are guidelines for each of the subnets:

![]() Network address: All 0 bits in the host portion of the address

Network address: All 0 bits in the host portion of the address

![]() First host address: All 0 bits plus a rightmost 1 bit in the host portion of the address

First host address: All 0 bits plus a rightmost 1 bit in the host portion of the address

![]() Last host address: All 1 bits plus a rightmost 0 bit in the host portion of the address

Last host address: All 1 bits plus a rightmost 0 bit in the host portion of the address

![]() Broadcast address: All 1 bits in the host portion of the address

Broadcast address: All 1 bits in the host portion of the address

As shown in Figure 8-8, the first host address for the 192.168.1.0/25 network is 192.168.1.1, and the last host address is 192.168.1.126.

Figure 8-9 shows that the first host address for the 192.168.1.128/25 network is 192.168.1.129, and the last host address is 192.168.1.254.

To assign the first host address in each subnet to the router interface for that subnet, use the ip address command in interface configuration mode, as shown in Figure 8-10. Notice that each subnet uses the subnet mask of 255.255.255.128 to indicate that the network portion of the address is 25 bits.

A host configuration for the 192.168.1.128/25 network is shown in Figure 8-11. Notice that the gateway IP address is the address configured on the G0/1 interface of R1, 192.168.1.129, and the subnet mask is 255.255.255.128.

Subnetting Formulas (8.1.2.3)

In this section we take a look at some basic formulas that will assist you in subnetting.

2^n (where n = the number of bits borrowed)

As shown in Figure 8-12, for the 192.168.1.0/25 example, the calculation looks like this:

2^1 = 2 subnets

Calculating Hosts

Use this formula to calculate the number of hosts per network:

2^n (where n = the number of bits remaining in the host field)

As shown in Figure 8-13, for the 192.168.1.0/25 example, the calculation looks like this:

2^7 = 128

Because hosts cannot use the network address or broadcast address from a subnet, two of these addresses are not valid for host assignment. This means that each of the subnets has 126 (128 – 2) valid host addresses.

So in this example, borrowing 1 host bit toward the network results in creating two subnets, and each subnet can have a total of 126 hosts assigned.

Creating 4 Subnets (8.1.2.4)

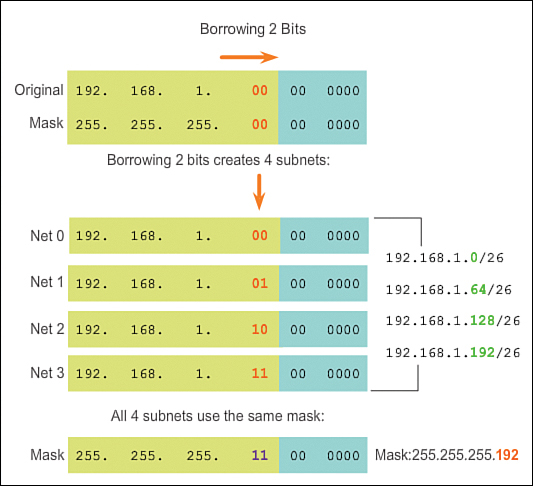

Consider an internetwork that requires three subnets. Using the same 192.168.1.0/24 address block, host bits must be borrowed to create at least three subnets. Borrowing a single bit would provide only two subnets. To provide more networks, more host bits must be borrowed. Calculate the number of subnets created if 2 bits are borrowed using the formula 2^number of bits borrowed:

2^2 = 4 subnets

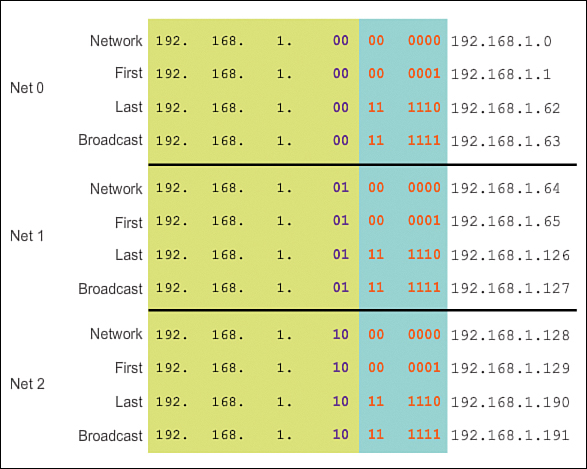

Borrowing 2 bits creates four subnets, as shown in Figure 8-14.

Recall that the subnet mask must change to reflect the borrowed bits. In this example, when 2 bits are borrowed, the mask is extended 2 bits into the last octet. In decimal, the mask is represented as 255.255.255.192, because the last octet is 1100 0000 in binary.

Host Calculation

To calculate the number of hosts, examine the last octet. After borrowing 2 bits for the subnet, there are 6 host bits remaining.

Apply the following host calculation formula as shown in Figure 8-15:

2^6 = 64

But remember that all 0 bits in the host portion of the address is the network address, and all 1s in the host portion is a broadcast address. Therefore, there are only 62 host addresses that are actually available for each subnet.

As shown in Figure 8-16, the first host address for the first subnet is 192.168.1.1 and the last host address is 192.168.1.62.

Figure 8-17 shows the ranges for subnets 0, 1, and 2. Remember that each host must have a valid IP address within the range defined for that network segment. The subnet assigned to the router interface will determine which segment a host belongs to.

Figure 8-18 shows a sample configuration in which the first network is assigned to the GigabitEthernet 0/0 interface, the second network is assigned to the GigabitEthernet 0/1 interface, and the third network is assigned to the Serial 0/0/0 network.

Again, using a common addressing plan, the first host address in the subnet is assigned to the router interface. Hosts on each subnet will use the address of the router interface as the default gateway address:

![]() PC1 (192.168.1.2/26) will use 192.168.1.1 (G0/0 interface address of R1) as its default gateway address.

PC1 (192.168.1.2/26) will use 192.168.1.1 (G0/0 interface address of R1) as its default gateway address.

![]() PC2 (192.168.1.66/26) will use 192.168.1.65 (G0/1 interface address of R1) as its default gateway address.

PC2 (192.168.1.66/26) will use 192.168.1.65 (G0/1 interface address of R1) as its default gateway address.

Note

All devices on the same subnet will have a host IPv4 address from the range of host addresses and will use the same subnet mask.

Creating 8 Subnets (8.1.2.5)

Next, consider an internetwork that requires five subnets, as shown in Figure 8-19.

Using the same 192.168.1.0/24 address block, host bits must be borrowed to create at least five subnets. Borrowing 2 bits would provide only four subnets, as shown in the previous example. To provide more networks, more host bits must be borrowed. Calculate the number of subnets created if 3 bits are borrowed using the following formula:

2^3 = 8 subnets

As shown in Figures 8-20 and 8-21, borrowing 3 bits creates eight subnets. When 3 bits are borrowed, the subnet mask is extended 3 bits into the last octet (/27), resulting in a subnet mask of 255.255.255.224. All devices on these subnets will use the subnet mask 255.255.255.224 (/27).

Host Calculation

To calculate the number of hosts, examine the last octet. After borrowing 3 bits for the subnet, there are 5 host bits remaining.

Apply the host calculation formula, 2^5 = 32, but subtract 2 for the all 0s in the host portion (network address) and all 1s in the host portion (broadcast address).

The subnets are assigned to the network segments required for the topology, as shown in Figure 8-22.

Again, using a common addressing plan, the first host address in the subnet is assigned to the router interface, as shown in Figure 8-23.

Hosts on each subnet will use the address of the router interface as the default gateway address:

![]() PC1 (192.168.1.2/27) will use 192.168.1.1 as its default gateway address.

PC1 (192.168.1.2/27) will use 192.168.1.1 as its default gateway address.

![]() PC2 (192.168.1.34/27) will use 192.168.1.33 as its default gateway address.

PC2 (192.168.1.34/27) will use 192.168.1.33 as its default gateway address.

![]() PC3 (192.168.1.98/27) will use 192.168.1.97 as its default gateway address.

PC3 (192.168.1.98/27) will use 192.168.1.97 as its default gateway address.

![]() PC4 (192.168.1.130/27) will use 192.168.1.129 as its default gateway address.

PC4 (192.168.1.130/27) will use 192.168.1.129 as its default gateway address.

Activity 8.1.2.6: Determining the Network Address (Basic)

Go to the online course to perform this practice activity of determining the network address.

Activity 8.1.2.7: Calculate the Number of Valid Hosts (Basic)

Go to the online course to perform this practice activity of determining the number of hosts.

Activity 8.1.2.8: Determining the Valid Addresses for Hosts (Basic)

Go to the online course to perform this practice activity.

Activity 8.1.2.9: Calculate the Subnet Mask

Go to the online course to perform this practice activity.

Creating 100 Subnets with a /16 Prefix (8.1.2.10)

In the previous examples, we considered an internetwork that required three subnets and an internetwork that required five subnets. To achieve the goal of creating four subnets, we borrowed 2 bits from the 8 host bits available with an IP address that has a default mask of 255.255.255.0, or a /24 prefix. The resulting subnet mask was 255.255.255.192, and a total of four possible subnets were created. Applying the host calculation formula of 2^6 – 2, we determined that on each of those four subnets we could have 62 host addresses to assign to nodes.

To acquire five subnets, we borrowed 3 bits from the 8 host bits available with an IP address that has a default mask of 255.255.255.0, or a /24 prefix. In borrowing those 3 bits from the host portion of the address, we left 5 host bits remaining. The resulting subnet mask was 255.255.255.224, with a total of eight subnets created, and 30 host addresses per subnet.

Consider large organizations or campuses with an internetwork that requires 100 subnets. Just as in the previous examples, to achieve the goal of creating 100 subnets, we must borrow bits from the host portion of the IP address of the existing internetwork. As before, to calculate the number of subnets, we must look at the number of available host bits and use the subnet calculation formula 2^number of bits borrowed. Using the IP address of the last example, 192.168.10.0/24, we have 8 host bits; to create 100 subnets, we must borrow 7 bits. Calculate the number of subnets if 7 bits are borrowed: 2^7 = 128 subnets.

However, borrowing 7 bits will leave just 1 remaining host bit, and if we apply the host calculation formula, the result would be no hosts on these subnets. Calculate the number of hosts if 1 bit is remaining, 2^1 = 2, and then subtract 2 for the network address and the network broadcast; the result is 0 hosts (2^1 – 2 = 0).

In a situation requiring a larger number of subnets, an IP network is required that has more host bits to borrow from, such as an IP address with a default subnet mask of /16, or 255.255.0.0. Addresses that have a range of 128–191 in the first octet have a default mask of 255.255.0.0, or /16. Addresses in this range have 16 bits in the network portion and 16 bits in the host portion. The 16 bits that are in the host portion are the bits that are available to be borrowed for creating subnets.

Using a new IP address of 172.16.0.0/16 address block, host bits must be borrowed to create at least 100 subnets. Starting from left to right with the first available host bit, we will borrow a single bit at a time until we reach the number of bits necessary to create 100 subnets. Borrowing 1 bit, we would create two subnets; borrowing 2 bits, we would create four subnets; borrowing 3 bits, we would create eight subnets; and so on. Calculate the number of subnets created if 7 bits are borrowed using the formula 2^number of bits borrowed:

2^7 = 128 subnets

Borrowing 7 bits creates 128 subnets, as shown in Figure 8-24.

Recall that the subnet mask must change to reflect the borrowed bits. In this example, when 7 bits are borrowed, the mask is extended 7 bits into the third octet. In decimal, the mask is represented as 255.255.254.0, or a /23 prefix, because the third octet is 11111110 in binary and the fourth octet is 00000000 in binary. Subnetting will be done in the third octet, with the host bits in the third and fourth octets.

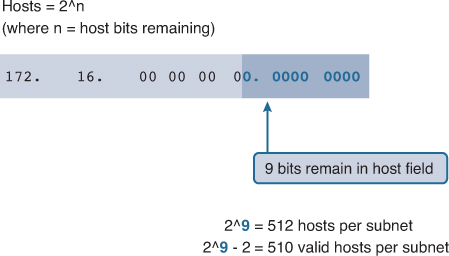

Calculating the Hosts (8.1.2.11)

To calculate the number of hosts, examine the third and fourth octets. After borrowing 7 bits for the subnet, there is 1 host bit remaining in the third octet and 8 host bits remaining in the fourth octet.

Apply the following host calculation formula as shown in Figure 8-25:

2^9 = 512

But remember that all 0 bits in the host portion of the address is the network address, and all 1s in the host portion is a broadcast address. Therefore, there are only 510 host addresses that are actually available for each subnet.

As shown in Figure 8-26, the first host address for the first subnet is 172.16.0.1 and the last host address is 172.16.1.254. Remember that each host must have a valid IP address within the range defined for that network segment. The subnet assigned to the router interface will determine which segment a host belongs to.

Note

Remember that bits can be borrowed only from the host portion of the address. The network portion of the address is allocated by the service provider and cannot be changed. So, organizations that require a significant number of subnets are required to communicate this need to their ISP so that the ISP can allocate an IP address block with a default mask that has enough bits to create the needed subnets.

Creating 1000 Subnets with a /8 Prefix (8.1.2.12)

Some organizations, such as small service providers, might need more than 100 subnets. Consider, for example, an organization that requires 1000 subnets. As always, to create subnets, we must borrow bits from the host portion of the IP address of the existing internetwork. As before, to calculate the number of subnets, it is necessary to look at the number of available host bits. A situation such as this requires that the IP address assigned by the ISP have enough host bits available to calculate 1000 subnets. IP addresses that have the range of 1–126 in the first octet have a default mask of 255.0.0.0 or /8. This means there are 8 bits in the network portion and 24 host bits available to borrow toward subnetting.

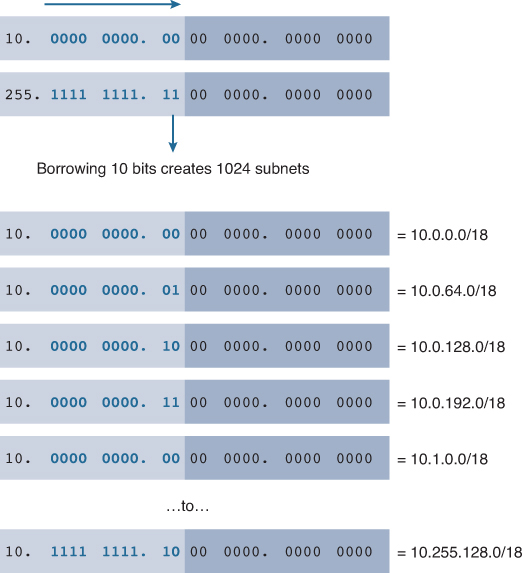

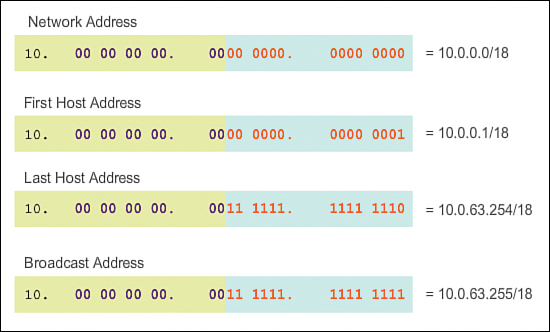

Using the 10.0.0.0/8 address block, host bits must be borrowed to create at least 1000 subnets. Starting from left to the right with the first available host bit, we will borrow a single bit at a time until we reach the number of bits necessary to create 1000 subnets. Calculate the number of subnets created if 10 bits are borrowed using the formula 2^number of bits borrowed:

2^10 = 1024 subnets

Borrowing 10 bits creates 1024 subnets, as shown in Figure 8-27.

Recall that the subnet mask must change to reflect the borrowed bits. In this example, when 10 bits are borrowed, the mask is extended 10 bits into the third octet. In decimal, the mask is represented as 255.255.192.0 or a /18 prefix, because the third octet of the subnet mask is 11000000 in binary and the fourth octet is 00000000 in binary. Subnetting will be done in the third octet, but don’t forget about the host bits in the third and fourth octets.

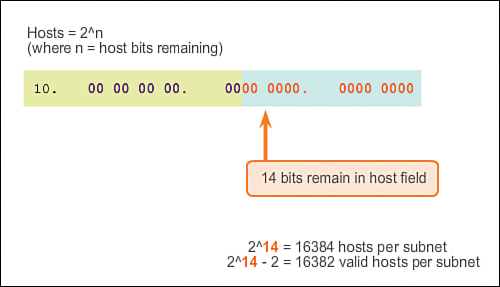

Host Calculation

To calculate the number of hosts, examine the third and fourth octet. After borrowing 10 bits for the subnet, there are 6 host bits remaining in the third octet and 8 host bits remaining in the fourth octet. A total of 14 host bits remain.

Apply the following host calculation formula as shown in Figure 8-28:

2^14 – 2 = 16382

The first host address for the first subnet is 10.0.0.1 and the last host address is 10.0.63.254, as shown in Figure 8-29. Remember that each host must have a valid IP address within the range defined for that network segment. The subnet assigned to the router interface will determine which segment a host belongs to.

Note

All devices on the same subnet will have a host IPv4 address from the range of host addresses and will use the same subnet mask.

Activity 8.1.2.13: Determining the Network Address – Advanced

Go to the online course to perform this practice activity.

Activity 8.1.2.14: Calculating the Number of Hosts – Advanced

Go to the online course to perform this practice activity.

Activity 8.1.2.15: Determining the Valid Addresses for Hosts – Advanced

Go to the online course to perform this practice activity.

Determining the Subnet Mask (8.1.3)

This section covers the parameters for determining the subnet mask you require.

Subnetting Based on Host Requirements (8.1.3.1)

The decision about how many host bits to borrow to create subnets is an important planning decision. There are two considerations when planning subnets: the number of host addresses required for each network, and the number of individual subnets needed. The selection of the number of bits for the subnet ID affects both the number of possible subnets and the number of host addresses in each subnet.

Video 8.1.3.1: Subnet Possibilities

This video shows the subnet possibilities for the 192.168.1.0 network. Go to the online course to view this animation.

Notice that there is an inverse relationship between the number of subnets and the number of hosts. The more bits borrowed to create subnets, the fewer host bits available; therefore, fewer hosts per subnet. If more host addresses are needed, more host bits are required, resulting in fewer subnets.

Number of Hosts

When borrowing bits to create multiple subnets, you leave enough host bits for the largest subnet. The number of host addresses required in the largest subnet will determine how many bits must be left in the host portion. The formula 2^n (where n is the number of host bits remaining) is used to calculate how many addresses will be available on each subnet. Recall that two of the addresses cannot be used, so that the usable number of addresses can be calculated as 2^n – 2.

Subnetting Network-Based Requirements (8.1.3.2)

Sometimes an organization may require a certain number of subnets, with less emphasis on the number of host addresses per subnet. This may be the case if an organization chooses to separate its network traffic based on internal structure or department setup. For example, an organization may choose to put all host devices used by employees in the Engineering department in one network, and all host devices used by management in a separate network, as shown in Figure 8-30. In this case, the number of subnets is most important in determining how many bits to borrow.

Recall that the number of subnets created when bits are borrowed can be calculated using the formula 2^n (where n is the number of bits borrowed). There is no need to subtract any of the resulting subnets, as they are all usable.

The key is to balance the number of subnets needed and the number of hosts required for the largest subnet. More bits borrowed to create additional subnets means fewer hosts available per subnet.

Subnetting to Meet Network Requirements (8.1.3.3, 8.1.3.4)

Every network within an organization is designed to accommodate a finite number of hosts. Basic subnetting requires enough subnets to accommodate the networks while also providing enough host addresses per subnet.

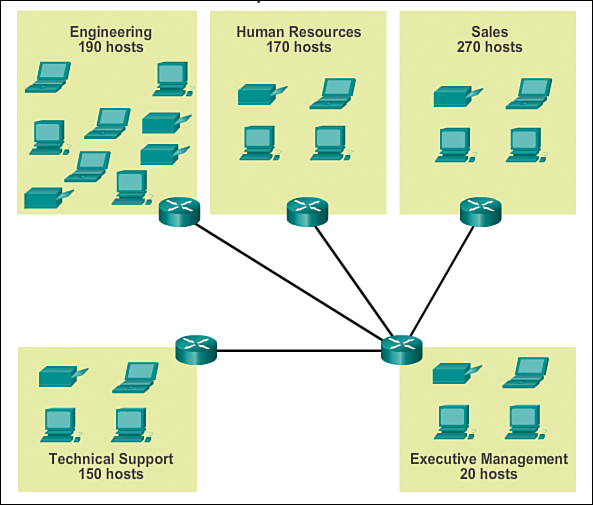

Some networks, such as point-to-point wide area network (WAN) links, require only two hosts. Other networks, such as a user LAN in a large building or department, may need to accommodate hundreds of hosts. Network administrators must devise the internetwork addressing scheme to accommodate the maximum number of hosts for each network. The number of hosts in each division should allow for growth in the number of hosts.

Determine the Total Number of Hosts

First, consider the total number of hosts required by the entire corporate internetwork. A block of addresses large enough to accommodate all devices in all the corporate networks must be used. These devices include end-user devices, servers, intermediate devices, and router interfaces.

Consider the example of a corporate internetwork that must accommodate a total of 800 hosts in its five locations, as depicted in Figure 8-31.

In this example, the service provider has allocated a network address of 172.16.0.0/22 (10 host bits). As shown in Figure 8-32, this will provide 1022 host addresses, which will more than accommodate the addressing needs for this internetwork.

Determine the Number and Size of the Networks

Next, consider the number of subnets required and the number of host addresses needed on each subnet. Based on the network topology consisting of five LAN segments and four internetwork connections between routers, nine subnets are required. The largest subnet requires 40 hosts. When designing an addressing scheme, you should anticipate growth in both the number of subnets and the number of hosts per subnet.

The 172.16.0.0/22 network address has 10 host bits. Because the largest subnet requires 40 hosts, a minimum of 6 host bits should be borrowed. This is determined by using this formula: 2^6 – 2 = 62 hosts. The 4 remaining host bits can be used to allocate subnets. Using the formula for determining subnets, this results in 16 subnets: 2^4 = 16. Because the example internetwork requires nine subnets, this will meet the requirement and allow for some additional growth.

When 4 bits are borrowed, the new prefix length is /26 with a subnet mask of 255.255.255.192.

As shown in Figure 8-33, using the /26 prefix length, the 16 subnet addresses can be determined. Only the subnet portion of the address is incremented. The original 22 bits of the network address cannot change and the host portion will contain all 0 bits.

Note

Because the subnet portion is in both the third and fourth octets, one or both of these values will vary in the subnet addresses.

As shown in Figure 8-34, the original 172.16.0.0/22 network was a single network with 10 host bits, providing 1022 usable addresses to assign to hosts. By borrowing 4 host bits, 16 subnets (0000 through 1111) can be created. Each subnet has 6 host bits or 62 usable host addresses per subnet.

As shown in Figure 8-35, the subnets can be assigned to the LAN segments and router-to-router connections.

Activity 8.1.3.5: Determining the Number of Bits to Borrow

Go to the online course to perform this practice activity.

Packet Tracer Activity 8.1.3.6: Subnetting Scenario 1

In this activity, you are given the network address of 192.168.100.0/24 to subnet and provide the IP addressing for the network shown in the topology. Each LAN in the network requires enough space for, at least, 25 addresses for end-user devices, the switch, and the router. The connection between R1 to R2 will require an IP address for each end of the link.

Packet Tracer Activity 8.1.3.7: Subnetting Scenario 2

In this activity, you are given the network address of 172.31.1.0/24 to subnet and provide the IP addressing for the network shown in the topology. The required host addresses for each WAN and LAN link are labeled in the topology.

Lab 8.1.3.8: Calculating IPv4 Subnets

In this lab, you will complete the following objectives:

![]() Part 1: Determine IPv4 Address Subnetting

Part 1: Determine IPv4 Address Subnetting

![]() Part 2: Calculate IPv4 Address Subnetting

Part 2: Calculate IPv4 Address Subnetting

Lab 8.1.3.9: Subnetting Network Topologies

In this lab you will have to determine the number of subnets, design an appropriate addressing scheme, assign IP address and subnet mask to the interface, and examine the use of the available network address space and future growth potential.

Lab 8.1.3.10: Researching Subnet Calculators

In this lab, you will complete the following objectives:

![]() Part 1: Review Available Subnet Calculators

Part 1: Review Available Subnet Calculators

![]() Part 2: Perform Network Calculations Using a Subnet Calculator

Part 2: Perform Network Calculations Using a Subnet Calculator

Benefits of Variable Length Subnet Masking (8.1.4)

This section addresses some of the benefits of Variable Length Subnet Masking.

Traditional Subnetting Wastes Addresses (8.1.4.1)

Using traditional subnetting allocates the same number of addresses for each subnet. If all the subnets happened to have the same requirements for the number of hosts, these fixed-size address blocks would be efficient. However, most often that is not the case.

For example, the topology shown in Figure 8-36 requires seven subnets, one for each of the four LANs and one for each of the three WAN connections between routers. Using traditional subnetting with the given address of 192.168.20.0/24, 3 bits can be borrowed from the host portion in the last octet to meet the subnet requirement of seven subnets.

As shown in Figure 8-37, borrowing 3 bits creates eight subnets and leaves 5 host bits with 30 usable hosts per subnet. This scheme creates the needed subnets and meets the host requirement of the largest LAN.

Although this traditional subnetting meets the needs of the largest LAN and divides the address space into an adequate number of subnets, it results in significant waste of unused addresses.

For example, only two addresses are needed in each subnet for the three WAN links. Because each subnet has 30 usable addresses, there are 28 unused addresses in each of these subnets. As shown in Figure 8-38, this results in 84 unused addresses (28 × 3).

Further, this limits future growth by reducing the total number of subnets available. This inefficient use of addresses is characteristic of traditional subnetting of classful networks.

Applying a traditional subnetting scheme to this scenario is not very efficient and is wasteful. In fact, this example is a good model for showing how subnetting a subnet can be used to maximize address utilization.

Subnetting a subnet, or using Variable Length Subnet Mask (VLSM), was designed to avoid wasting addresses.

VLSM (8.1.4.2)

In all of the previous examples of subnetting, notice that the same subnet mask was applied for all the subnets. This means that each subnet has the same number of available host addresses.

As illustrated in Figure 8-39, traditional subnetting creates subnets of equal size. Each subnet in a traditional scheme uses the same subnet mask.

As shown in Figure 8-40, VLSM allows a network space to be divided in unequal parts. With VLSM, the subnet mask will vary depending on how many bits have been borrowed for a particular subnet, thus the “variable” part of the term VLSM.

VLSM subnetting is similar to traditional subnetting in that bits are borrowed to create subnets. The formulas to calculate the number of hosts per subnet and the number of subnets created still apply. The difference is that subnetting is not a single-pass activity. With VLSM, the network is first subnetted, and then the subnets are subnetted again. This process can be repeated multiple times to create subnets of various sizes.

Basic VLSM (8.1.4.3)

To better understand the VLSM process, consider again the previous example, shown in Figure 8-41, in which the network 192.168.20.0/24 is subnetted into eight equal-sized subnets; seven of the eight subnets are allocated. Four subnets are used for the LANs, and three subnets are used for the WAN connections between the routers. The wasted address space is in the subnets used for the WAN connections, because those subnets require only two usable addresses: one for each router interface. To avoid this waste, VLSM can be used to create smaller subnets for the WAN connections.

In Figure 8-42, the last subnet, 192.168.20.224/27, will be further subnetted.

Recall that when the number of host addresses needed is known, the formula 2^n – 2 (where n equals the number of host bits remaining) can be used. To provide two usable addresses, 2 host bits must be left in the host portion:

2^2 – 2 = 2

Because there are 5 host bits in the 192.168.20.224/27 address space, 3 bits can be borrowed, leaving 2 bits in the host portion.

The calculations at this point are exactly the same as those used for traditional subnetting. The bits are borrowed and the subnet ranges are determined.

As shown in Figure 8-42, this VLSM subnetting scheme reduces the number of addresses per subnet to a size appropriate for the WANs. Subnetting subnet 7 for WANs allows subnets 4, 5, and 6 to be available for future networks and allows several other subnets to be available for WANs.

VLSM in Practice (8.1.4.4)

Using the VLSM subnets, the LAN and WAN segments can be addressed without unnecessary waste. The hosts in each of the LANs will be assigned a valid host address with the range for that subnet and a /27 mask. Each of the four routers will have a LAN interface with a /27 subnet and one or more serial interfaces with a /30 subnet.

Using a common addressing scheme, the first host IPv4 address for each subnet is assigned to the LAN interface of the router. The WAN interfaces of the routers are assigned the IP addresses and mask for the /30 subnets.

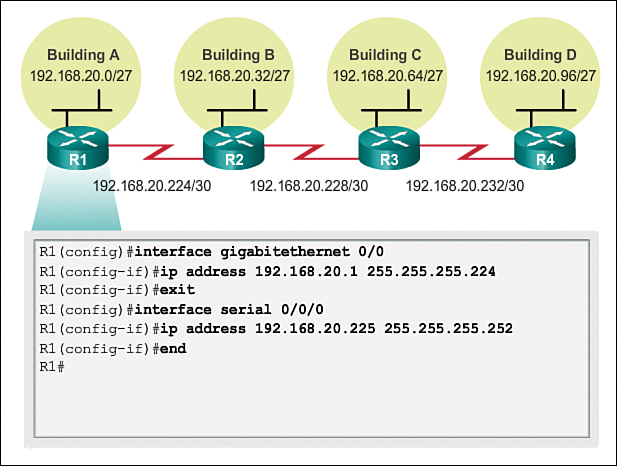

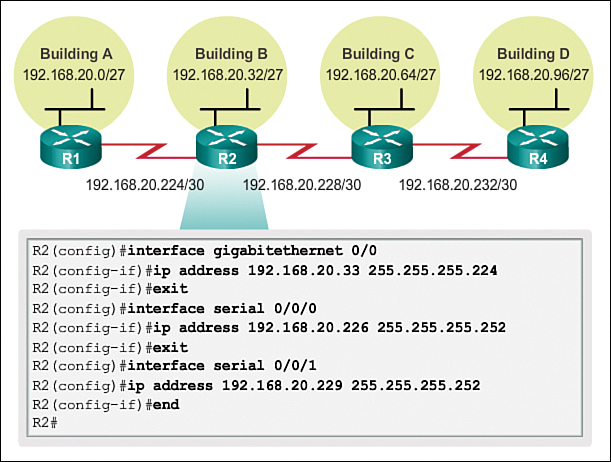

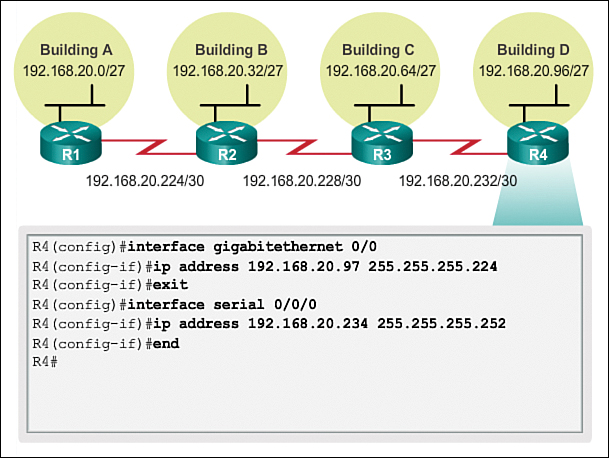

Figures 8-43 through 8-46 show the interface configuration for each of the routers. Hosts on each subnet will have a host IPv4 address from the range of host addresses for that subnet and an appropriate mask. Hosts will use the address of the attached router LAN interface as the default gateway address.

![]() Building A hosts (192.168.20.0/27) will use router interface address 192.168.20.1 as the default gateway address.

Building A hosts (192.168.20.0/27) will use router interface address 192.168.20.1 as the default gateway address.

![]() Building B hosts (192.168.20.32/27) will use router interface address 192.168.20.33 as the default gateway address.

Building B hosts (192.168.20.32/27) will use router interface address 192.168.20.33 as the default gateway address.

![]() Building C hosts (192.168.20.64/27) will use router interface address 192.168.20.65 as the default gateway address.

Building C hosts (192.168.20.64/27) will use router interface address 192.168.20.65 as the default gateway address.

![]() Building D hosts (192.168.20.96/27) will use router interface address 192.168.20.97 as the default gateway address.

Building D hosts (192.168.20.96/27) will use router interface address 192.168.20.97 as the default gateway address.

VLSM Chart (8.1.4.5)

Address planning can also be accomplished using a variety of tools. One method is to use a VLSM chart to identify which blocks of addresses are available for use and which ones are already assigned. This method helps to prevent assigning addresses that have already been allocated. Using the network from the previous example, the VLSM chart can be used to plan address assignment.

Examining the /27 Subnets

As shown in Figure 8-47, when using traditional subnetting, the first seven address blocks are allocated for LANs and WANs. Recall that this scheme results in eight subnets with 30 usable addresses each (/27). While this scheme works for the LAN segments, there are many wasted addresses in the WAN segments.

When designing the addressing scheme on a new network, the address blocks can be assigned in a way that minimizes waste and keeps unused blocks of addresses contiguous.

Assigning VLSM Address Blocks

As shown in Figure 8-48, in order to use the address space more efficiently, the following /30 subnets are created for WAN links. To keep the unused blocks of addresses together, the last /27 subnet is further subnetted to create the /30 subnets. The first three subnets are assigned to WAN links.

![]() .224 /30 host address range 225 to 226: WAN link between R1 and R2

.224 /30 host address range 225 to 226: WAN link between R1 and R2

![]() .228 /30 host address range 229 to 230: WAN link between R2 and R3

.228 /30 host address range 229 to 230: WAN link between R2 and R3

![]() .232 /30 host address range 233 to 234: WAN link between R3 and R4

.232 /30 host address range 233 to 234: WAN link between R3 and R4

![]() 236 /30 host address range 237 to 238: Available to be used

236 /30 host address range 237 to 238: Available to be used

![]() 240 /30 host address range 241 to 242: Available to be used

240 /30 host address range 241 to 242: Available to be used

![]() .244 /30 host address range 245 to 246: Available to be used

.244 /30 host address range 245 to 246: Available to be used

![]() .248 /30 host address range 249 to 250: Available to be used

.248 /30 host address range 249 to 250: Available to be used

![]() .252 /30 host address range 253 to 254: Available to be used

.252 /30 host address range 253 to 254: Available to be used

Designing the addressing scheme in this way leaves three unused /27 subnets and five unused /30 subnets.

Activity 8.1.4.6: Practicing VLSM

Go to the online course to perform this practice activity.

Addressing Schemes (8.2)

There are several addressing schemes that can be used; this section looks at some of them.

Structured Design (8.2.1)

The first schemes we will examine are the structure design schemes.

Planning to Address the Network (8.2.1.1)

As shown in Figure 8-49, the allocation of network layer address space within the corporate network needs to be well designed. Address assignment should not be random. There are three primary considerations when planning address allocation:

![]() Preventing duplication of addresses: Each host in an internetwork must have a unique address. Without the proper planning and documentation, an address could be assigned to more than one host, resulting in access issues for both hosts.

Preventing duplication of addresses: Each host in an internetwork must have a unique address. Without the proper planning and documentation, an address could be assigned to more than one host, resulting in access issues for both hosts.

![]() Providing and controlling access: Some hosts, such as servers, provide resources to internal hosts as well as to external hosts. The Layer 3 address assigned to a server can be used to control access to that server. If, however, the address is randomly assigned and not well documented, controlling access is more difficult.

Providing and controlling access: Some hosts, such as servers, provide resources to internal hosts as well as to external hosts. The Layer 3 address assigned to a server can be used to control access to that server. If, however, the address is randomly assigned and not well documented, controlling access is more difficult.

![]() Monitoring security and performance: Similarly, the security and performance of network hosts and the network as a whole must be monitored. As part of the monitoring process, network traffic is examined for addresses that are generating or receiving excessive packets. With proper planning and documentation of the network addressing, problematic network devices can be easily found.

Monitoring security and performance: Similarly, the security and performance of network hosts and the network as a whole must be monitored. As part of the monitoring process, network traffic is examined for addresses that are generating or receiving excessive packets. With proper planning and documentation of the network addressing, problematic network devices can be easily found.

Assigning Addresses Within a Network

Within a network, there are different types of devices, including

![]() End-user clients

End-user clients

![]() Servers and peripherals

Servers and peripherals

![]() Hosts that are accessible from the Internet

Hosts that are accessible from the Internet

![]() Intermediary devices

Intermediary devices

![]() Gateway

Gateway

When developing an IP addressing scheme, it is generally recommended to have a set pattern of how addresses are allocated to each type of device. This benefits administrators when adding and removing devices and when filtering traffic based on IP. It also simplifies documentation.

Assigning Addresses to Devices (8.2.1.2)

A network addressing plan might include using a different range of addresses within each subnet, for each type of device, as shown in Figure 8-50.

Addresses for Clients

Because of the challenges associated with static address management, end-user devices often have addresses dynamically assigned, using DHCP. DHCP is generally the preferred method of assigning IP addresses to hosts on large networks because it reduces the burden on network support staff and virtually eliminates entry errors.

Another benefit of DHCP is that an address is not permanently assigned to a host but rather is only leased for a period of time. If we need to change the subnetting scheme of our network, we do not have to statically reassign individual host addresses. With DHCP, we only need to reconfigure the DHCP server with the new subnet information. After this has been done, the hosts only need to automatically renew their IP addresses.

Addresses for Servers and Peripherals

Any network resource, such as a server or a printer, should have a static IP address. The client hosts access these resources using the IP addresses of these devices. Therefore, predictable addresses for each of these servers and peripherals are necessary.

Servers and peripherals are a concentration point for network traffic. There are many packets sent to and from the IPv4 addresses of these devices. When monitoring network traffic with a tool like Wireshark, a network administrator should be able to rapidly identify these devices. Using a consistent numbering system for these devices makes the identification easier.

Addresses for Hosts That Are Accessible from the Internet

In most internetworks, only a few devices are accessible by hosts outside of the corporation. For the most part, these devices are usually servers of some type. As with all devices in a network that provide network resources, the IP addresses for these devices should be static.

In the case of servers accessible by the Internet, each must have a public space address associated with it. Additionally, variations in the address of one of these devices will make that device inaccessible from the Internet. In many cases, these devices are on a network that is numbered using private addresses. This means that the router or firewall at the perimeter of the network must be configured to translate the internal address of the server into a public address. Because of this additional configuration in the perimeter intermediary device, it is even more important that these devices have a predictable address.

Addresses for Intermediary Devices

Intermediary devices are also a concentration point for network traffic. Almost all traffic within or between networks passes through some form of intermediary device. Therefore, these network devices provide an opportune location for network management, monitoring, and security.

Most intermediary devices are assigned Layer 3 addresses, either for the device management or for their operation. Devices, such as hubs, switches, and wireless access points, do not require IPv4 addresses to operate as intermediary devices. However, if we must access these devices as hosts to configure, monitor, or troubleshoot network operation, they must have addresses assigned.

Because we must know how to communicate with intermediary devices, they should have predictable addresses. Therefore, their addresses are typically assigned manually. Additionally, the addresses of these devices should be in a different range within the network block than user device addresses.

Address for the Gateway (Routers and Firewalls)

Unlike the other intermediary devices mentioned, routers and firewall devices have an IP address assigned to each interface. Each interface is in a different network and serves as the gateway for the hosts in that network. Typically, the router interface uses either the lowest or highest address in the network. This assignment should be uniform across all networks in the corporation so that network personnel will always know the gateway of the network no matter which network they are working on.

Router and firewall interfaces are the concentration point for traffic entering and leaving the network. Because the hosts in each network use a router or firewall device interface as the gateway out of the network, many packets flow through these interfaces. Therefore, these devices can play a major role in network security by filtering packets based on source and/or destination IP addresses. Grouping the different types of devices into logical addressing groups makes the assignment and operation of this packet filtering more efficient.

Lab 8.2.1.3: Designing and Implementing a Subnetted IPv4 Addressing Scheme

In this lab, you will complete the following objectives:

![]() Part 1: Design a Network Subnetting Scheme

Part 1: Design a Network Subnetting Scheme

![]() Part 2: Configure the Devices

Part 2: Configure the Devices

![]() Part 3: Test and Troubleshoot the Network

Part 3: Test and Troubleshoot the Network

Lab 8.2.1.4: Designing and Implementing a VLSM Addressing Scheme

In this lab, you will complete the following objectives:

![]() Part 1: Examine Network Requirements

Part 1: Examine Network Requirements

![]() Part 2: Design the VLSM Address Scheme

Part 2: Design the VLSM Address Scheme

![]() Part 3: Cable and Configure the IPv4 Network

Part 3: Cable and Configure the IPv4 Network

Packet Tracer Activity 8.2.1.5: Designing and Implementing a VLSM Addressing Scheme

In this activity you are given a network address to develop a VLSM addressing scheme for the network shown in the included topology.

Design Considerations for IPv6 (8.3)

This section looks at how to design an IPv6 network.

Subnetting an IPv6 Network (8.3.1)

As shown in this section, the rules for subnetting an IPv6 network are entirely different from the rules for subnetting an IPv4 network.

Subnetting Using the Subnet ID (8.3.1.1)

IPv6 subnetting requires a different approach from that taken in IPv4 subnetting, primarily because IPv6 has so many addresses that the reason for subnetting is completely different. An IPv6 address space is not subnetted to conserve addresses; rather, it is subnetted to support hierarchical, logical design of the network. Whereas IPv4 subnetting is about managing address scarcity, IPv6 subnetting is about building an addressing hierarchy based on the number of routers and the networks they support.

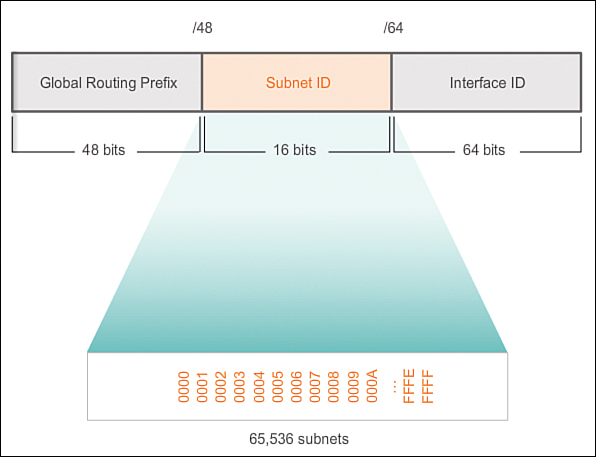

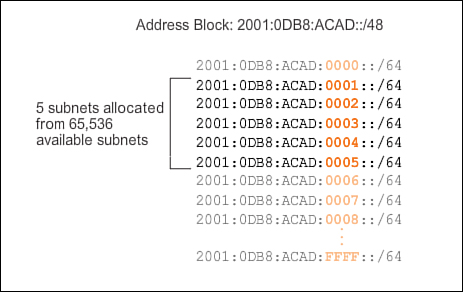

Recall that an IPv6 address block with a /48 prefix has 16 bits for the Subnet ID, as shown in Figure 8-51. Subnetting using the 16-bit Subnet ID yields a possible 65,536 /64 subnets and does not require borrowing any bits from the Interface ID, or host portion, of the address. Each IPv6 /64 subnet contains roughly 18 quintillion addresses, obviously more than will ever be needed in one IP network segment.

Subnets created from the subnet ID are easy to represent because no conversion to binary is required. To determine the next available subnet, just count up in hexadecimal. As shown in Figure 8-52, this means counting by hexadecimal in the subnet ID portion.

The global routing prefix is the same for all subnets. Only the subnet ID quartet is incremented for each subnet.

IPv6 Subnet Allocation (8.3.1.2)

With more than 65,000 subnets to choose from, the task of the network administrator becomes one of designing a logical scheme to address the network.

As shown in Figure 8-53, the example topology will require subnets for each LAN as well as for the WAN link between R1 and R2. Unlike the example for IPv4, with IPv6 the WAN link subnet will not be subnetted further. Although this may “waste” addresses, that is not a concern when using IPv6.

As shown in Figure 8-54, the allocation of five IPv6 subnets, with the Subnet ID field 0001 through 0005, will be used for this example. Each /64 subnet will provide more addresses than will ever be needed.

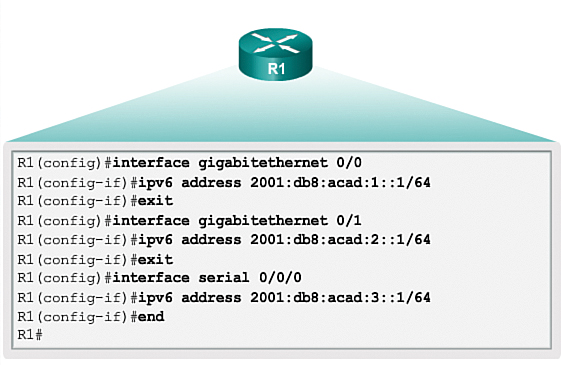

As shown in Figure 8-55, each LAN segment and the WAN link are assigned a /64 subnet.

Similar to configuring IPv4, Figure 8-56 shows that each of the router interfaces has been configured to be on a different IPv6 subnet.

Subnetting into the Interface ID (8.3.1.3)

Similar to borrowing bits from the host portion of an IPv4 address, with IPv6, bits can be borrowed from the interface ID to create additional IPv6 subnets. This is typically done for security reasons, to create fewer hosts per subnet, and not necessarily to create additional subnets.

When extending the subnet ID by borrowing bits from the interface ID, the best practice is to subnet on a nibble boundary. A nibble is 4 bits, or one hexadecimal digit. As shown in Figure 8-57, the /64 subnet prefix is extended 4 bits or 1 nibble to /68. Doing this reduces the size of the interface ID by 4 bits, from 64 to 60 bits.

Subnetting on nibble boundaries means only using nibble-aligned subnet masks. Starting at /64, the nibble-aligned subnet masks are /68, /72, /76, /80, etc.

Subnetting on a nibble boundary creates subnets by using the additional hexadecimal value. In Figure 8-57, the new subnet ID consists of the five hexadecimal values ranging from 00000 through FFFFF.

It is possible to subnet within a nibble boundary, within a hexadecimal digit, but it is not recommended or even necessary. Subnetting within a nibble takes away the advantage of easily determining the prefix from the interface ID. For example, if a /66 prefix length is used, the first 2 bits would be part of the subnet ID and the second 2 bits would be part of the interface ID.

Packet Tracer Activity 8.3.1.4: Implementing a Subnetted IPv6 Addressing Scheme

In this activity your network administrator wants you to assign five /64 IPv6 subnets to the network shown in the topology. Your job is to determine the IPv6 subnets, assign IPv6 addresses to the routers, and set the PCs to automatically receive IPv6 addressing. Your final step is to verify connectivity between IPv6 hosts.

Summary (8.4)

Class Activity 8.4.1.1: Can You Call Me Now?

Note

This activity may be completed individually or in small/large groups using Packet Tracer software.

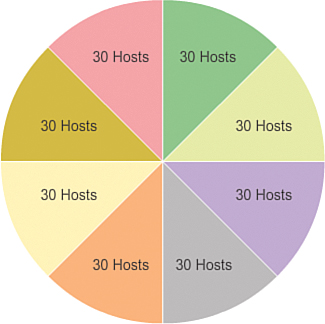

You are setting up a dedicated, computer addressing scheme for patient rooms in a hospital. The switch will be centrally located in the nurses’ station, as each of the five rooms will be wired so that patients can just connect to an RJ-45 port built into the wall of their room. Devise a physical and logical topology for only one of the six floors using the following addressing scheme requirements:

![]() There are six floors, with five patient rooms on each floor, for a total of 30 connections. Each room needs a network connection.

There are six floors, with five patient rooms on each floor, for a total of 30 connections. Each room needs a network connection.

![]() Subnetting must be incorporated into your scheme.

Subnetting must be incorporated into your scheme.

![]() Use one router, one switch, and five host stations for addressing purposes.

Use one router, one switch, and five host stations for addressing purposes.

![]() Validate that all PCs can connect to the hospital’s in-house services.

Validate that all PCs can connect to the hospital’s in-house services.

![]() Keep a copy of your scheme to share later with the class or learning community. Be prepared to explain how subnetting, unicasts, multicasts, and broadcasts would be incorporated, and where your addressing scheme could be used.

Keep a copy of your scheme to share later with the class or learning community. Be prepared to explain how subnetting, unicasts, multicasts, and broadcasts would be incorporated, and where your addressing scheme could be used.

Packet Tracer Activity 8.4.1.2: Skills Integration Challenge

As a network technician familiar with IPv4 and IPv6 addressing implementations, you are now ready to take an existing network infrastructure and apply your knowledge and skills to finalize the configuration. The network administrator has already configured some commands on the routers. Do not erase or modify those configurations. Your task is to complete the IPv4 and IPv6 addressing scheme, implement IPv4 and IPv6 addressing, and verify connectivity.

In this chapter you have learned how devices can be grouped into subnets, or smaller network groups, from a large network.

The process of segmenting a network by dividing it into multiple smaller network spaces is called subnetting, and is depicted in Figure 8-58.

Every network address has a valid range of host addresses. All devices attached to the same network will have an IPv4 host address for that network and a common subnet mask or network prefix. Traffic can be forwarded between hosts directly if they are on the same subnet. Traffic cannot be forwarded between subnets without the use of a router. To determine if traffic is local or remote, the router uses the subnet mask. The prefix and the subnet mask are different ways of representing the same thing—the network portion of an address.

IPv4 subnets are created by using one or more of the host bits as network bits. Two very important factors will lead to the determination of the IP address block with the subnet mask: the number of subnets required, and the maximum number of hosts needed per subnet. There is an inverse relationship between the number of subnets and the number of hosts. The more bits borrowed to create subnets, the fewer host bits available; therefore, fewer hosts per subnet.

The formula 2^n (where n is the number of host bits remaining) is used to calculate how many addresses will be available on each subnet. However, the network address and the broadcast address within a range are not useable; therefore, to calculate the useable number of addresses, the calculation 2^n – 2 is required.

Subnetting a subnet, or using VLSM, was designed to avoid wasting addresses.

IPv6 subnetting requires a different approach from that taken in IPv4 subnetting. An IPv6 address space is not subnetted to conserve addresses; rather, it is subnetted to support hierarchical, logical design of the network. So, while IPv4 subnetting is about managing address scarcity, IPv6 subnetting is about building an addressing hierarchy based on the number of routers and the networks they support.

Careful planning is required to make best use of the available address space. Size, location, use, and access requirements are all considerations in the address planning process.

After it is implemented, an IP network needs to be tested to verify its connectivity and operational performance.

Practice

The following activities provide practice with the topics introduced in this chapter. The Labs and Class Activities are available in the companion Network Basics Lab Manual (978-1-58713-313-8). The Packet Tracer Activities PKA files are found in the online course.

Class Activities

Class Activity 8.0.1.2: Call Me!

Class Activity 8.4.1.1: Can You Call Me Now?

Labs

Lab 8.1.3.8: Calculating IPv4 Subnets

Lab 8.1.3.9: Subnetting Network Topologies

Lab 8.1.3.10: Researching Subnet Calculators

Lab 8.2.1.3: Designing and Implementing a Subnetted IPv4 Addressing Scheme

Lab 8.2.1.4: Designing and Implementing a VLSM Addressing Scheme

Packet Tracer Activities

Packet Tracer Activity 8.1.3.6: Subnetting Scenario 1

Packet Tracer Activity 8.1.3.7: Subnetting Scenario 2

Packet Tracer Activity 8.2.1.5: Designing and Implementing a VLSM Addressing Scheme

Packet Tracer Activity 8.3.1.4: Implementing a Subnetted IPv6 Addressing Scheme

Packet Tracer Activity 8.4.1.2: Skills Integration Challenge

Check Your Understanding

Complete all the review questions listed here to test your understanding of the topics and concepts in this chapter. The appendix, “Answers to the ‘Check Your Understanding’ Questions,” lists the answers.

1. How many host bits must be borrowed from an IPv4 address in order to create exactly 32 subnets of equal size?

A. 3

B. 4

C. 5

D. 6

2. Given the subnet 192.168.1.0/26, what are the first and last valid host addresses of the first subnet?

A. 192.168.1.0 and 192.168.1.255

B. 192.168.1.1 and 192.168.1.254

C. 192.168.1.1 and 192.168.1.126

D. 192.168.1.0 and 192.168.1.63

E. 192.168.1.1 and 192.168.1.62

3. A PC has been assigned the IP address 192.168.0.168/29. How many more useable host addresses are left to be assigned on this network?

A. 1

B. 5

C. 6

D. 7

E. 13

F. 28

4. A host has been assigned an IP address and network prefix of 192.168.1.59/28. What is the network address of the subnet on which the host resides?

A. 192.168.1.0

B. 192.168.1.16

C. 192.168.1.32

D. 192.168.1.48

5. Which pair of hosts will require a router to forward packets between them?

A. Host A: 192.168.1.32/24 and host B: 192.168.1.64/24

B. Host A: 192.168.1.34/25 and host B: 192.168.1.55/25

C. Host A: 192.168.1.59/26 and host B: 192.168.1.71/26

D. Host A: 192.168.1.3/28 and host B: 192.168.1.12/28

6. What is the prefix notation for the subnet mask 255.255.254.0?

A. /23

B. /24

C. /25

D. /29

E. /30

F. /31

7. When applied to network 192.168.0.0, what subnet mask will yield 126 usable host addresses on two equally sized subnets?

A. 255.255.255.128

B. 255.255.255.240

C. 255.255.255.248

D. 255.255.255.252

8. A host is assigned the IP address of 192.31.7.200/28. Which two IP addresses could be used for other network devices on the same network? (Choose two.)

A. 192.31.7.1

B. 192.31.7.192

C. 192.31.7.193

D. 192.31.7.200

E. 192.31.7.208

F. 192.31.7.206

G. 192.31.7.222

9. What is the main reason that a network administrator would use VLSM?

A. Cost savings

B. Enhanced security

C. Efficient use of address space

D. Shorter delay of data transmissions

10. What is the size of a nibble in binary bits?

A. 2 bits

B. 4 bits

C. 8 bits

D. 16 bits

11. How many usable host addresses are on the same subnet as host 10.10.30.40/20?

A. 1022

B. 1024

C. 2047

D. 2048

E. 4094

F. 4096

12. What does the acronym VLSM stand for?

A. Variable length subnet mask

B. Very long subnet mask

C. Vociferous longitudinal subnet mask

D. Vector length subnet mask

E. Vector loop subnet mask

13. R1 has configured interface Fa0/0 with the ip address 10.5.48.1 255.255.240.0 command. Which of the following subnets, when configured on another interface on R1, would not be considered an overlapping VLSM subnet?

A. 10.5.0.0 255.255.240.0

B. 10.4.0.0 255.254.0.0

C. 10.5.32.0 255.255.224.0

D. 10.5.0.0 255.255.128.0

14. R4 has a connected route for 172.16.8.0/22. Which of the following answers lists a subnet that overlaps with this subnet?

A. 172.16.0.0/21

B. 172.16.6.0/23

C. 172.16.16.0/20

D. 172.16.11.0/25

15. A design already includes subnets 192.168.1.0/26, 192.168.1.128/30, and 192.168.1.160/29. Which of the following subnets is the numerically lowest subnet ID that could be added to the design, if you wanted to add a subnet that uses a /28 mask?

A. 192.168.1.144/28

B. 192.168.1.112/28

C. 192.168.1.64/28

D. 192.168.1.80/28

E. 192.168.1.96/28