WarGames Wirelessly

Like many of the beneficial technologies discussed in this book, wireless networks are also susceptible to a variety of threats; however, wireless is still a growing technology, and today you have the opportunity to protect and secure your network. This section takes a high-level look at some of those threats and why you should secure your network.

You might be familiar with the 1983 movie WarGames, where a young man (played by Matthew Broderick) finds a back door into a military computer and unknowingly starts the countdown to World War III. The movie’s young hacker executes this mayhem all over a modem, which coined the phrase wardialing.

Fast-forward almost 20 years when London-based author Ben Hammersley was writing, and he wanted a cup of coffee or even a bite to eat from the café across the street, but he still needed to work. Ben installed an access point that gave him the wireless access he wanted; he was a giving man, however, and decided to let his neighbors know that they could have free wireless Internet access as well. Disappointingly, no one took him up on his generosity. Enter Ben’s friend, Matt Jones, who posted a set of runes on a website (www.blackbeltjones.com) with the intention of creating a set of international symbols that would let people know that a wireless connection is available. Ben took a piece of chalk and drew these runes on the curb in front of the café and became the first warchalker (see Figure 10-4).

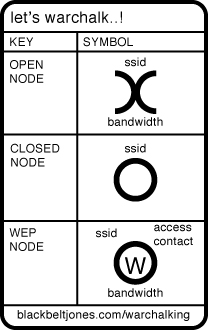

Figure 10-4 Warchalking Symbols

Shortly after Matt (also known as Black Belt Jones) posted these symbols on the Internet, word spread fast and these two individuals started an Internet phenomenon resulting in new words with such ominous names as warchalking, warspying, warspamming, and wardriving—all ultimately a part of the evolution of wireless access. To clarify, none of these terms enhance the security of your network. They are simply terms that attackers use to describe their activities. The following sections review each of these threats.

Warchalking

If you have ever seen a pirate movie in which a fancifully drawn treasure map displayed a large, red X depicting where the ill-gotten gains were buried, you have some basic idea what role symbology has played in man’s pursuit of riches. Much in the same way that the X marked the spot filled with gold, jewels, and silver, so did a series of runes depict areas of danger: which house a policeman might live in, or which houses were considered sympathetic to hobos during the Great Depression. For example, a rune in the shape of the pound sign (#) told fellow hobos that a crime had recently been committed and to avoid the area, or a casually drawn triangle might indicate that there were too many hobos working this area, so pickings were slim.

It was these hobo hieroglyphics from the Great Depression that inspired Ben and Matt to add a new dimension known as warchalking. Warchalking is a practice that originated with the intention of telling fellow wireless warriors where they could get a free wireless connection on a corporate or private wireless network. The symbols used by these warchalkers generally indicate whether the wireless AP is considered open or closed, depicted either by two half-circles back to back or a single regular circle, respectively, and what sort of security protects this AP.

Warchalking in its original form turned out to be a momentary cult-like movement that was fascinating for everyone. However, in practice it has changed significantly to reflect the realities of what people are trying to accomplish. Few people walk around drawing marks on buildings; however, people are “chalking” maps using GPSs to show exactly where wireless access can be gained. Searching the Internet reveals quite a few online maps marked for use (www.netstumbler.com/nation.php). One of the added benefits of putting the maps online is that they are not washed away when it rains.

From a security perspective, it is highly unlikely that you will ever see the side of your building or sidewalk marked with a warchalk symbol; however, it is likely that if your wireless network is not properly protected, it will appear chalked on someone’s map for anyone to use. You might be wondering how attackers find these APs. Consider the last time you saw anyone walking around with a laptop and a GPS. It does happen, but it might not be obvious because warwalkers typically use backpacks to conceal their activities. In addition to the limitations posed by equipment battery life, all this walking can become tiring. Enter the next wireless threat—wardriving—where converters can power a laptop for as long as the car is running.

Note

Wapchalking—A variant of warchalking set up by the Wireless Access Point Sharing Community, an informal group with a code of conduct that forbids the use of wireless APs without permission. The group uses the warchalking marks as an invitation to wireless users to join their community. In warchalking terms, the two half-moon open node mark means that a wireless access device is currently indicating factory default settings and is thus easily detected.

Wardriving

Wardriving makes finding open wireless networks simple and dramatically increases the search area exponentially. The act of wardriving is simple: You drive around looking for wireless networks. Before delving too deeply into this subject, remember that wardriving or LAN jacking an unwary subject’s WAP is possibly illegal, depending on the part of the country in which you live. This book does not imply that you should start security testing outside a sandbox that you own. It merely discusses the technical nature of such a white hat audit. Part of the appeal is that you can now use GPS systems connected to your laptop, which is then powered by your car. This makes the act of wardriving accurate and potentially rewarding for those looking for your wireless network because they can cover a much larger area with a vehicle.

It is disturbing that almost anyone can find your wireless network so easily, isn’t it? Vendors turn everything on by default, regardless of network security concerns; this makes it easy for wardrivers. By default, wireless APs broadcast a beacon frame that identifies (broadcasts the SSID) the wireless network they are a part of, every 10 milliseconds.

The average antennae on a wireless PCI card NIC is not sensitive enough to do a good job of zeroing in on low- to medium-powered WAP signals, so many wardrivers have resorted to using a USB wireless NIC outfitted with a homemade directional Yagi design antennae hardwired into the USB NIC, as shown in Figure 10-5. Various designs yield better or worse results depending on the signal type of the wireless traffic you are trying to snoop. The wireless network is identified by a 32-bit character known as a Service Set Identifier (SSID). For a wardriver, the easiest networks to find are those broadcasting this SSID. Perhaps you do not have any special applications but only a laptop with Windows. From a security perspective, Windows is wireless-aware and perhaps too friendly because it easily picks up any SSID broadcasts and automatically tries to join any available wireless network. With such a friendly operating system, who needs all the special tools?

Figure 10-5 Pringles Can Used as a Yagi Antenna

By default, the SSID is included in the header of the wireless packets broadcast every 10 milliseconds from a WAP. The SSID differentiates one WLAN from another, so all APs and all devices attempting to connect to a specific WLAN must use the same SSID. A device is not permitted to join the wireless network unless it can provide the unique SSID. Because an SSID can be sniffed from a packet in plain text, it does not supply any security to the network, even though it does function as a wireless network password. It is strongly recommended that WAPs have the broadcasting of their SSID disabled.

The presence of an SSID in a wireless network means that those engaging in the search should have more powerful wireless antennas that enable them to pick up and detect wireless signals. For example, if you want to “LAN jack” 802.11b 2.4-Ghz wireless network connections, you would most likely opt for a “helix” or “helical” design, which is basically tubular in design with a series of copper wire wrappings around a central core. This custom-made antennae style can be difficult to build because of its exacting standards and rather pricey parts list. On the other hand, a “wave guide” style can be made from rather inexpensive components such as a Pringles can (as shown in Figure 10-5), coffee can, or juice can.

Depending on your frame of reference (and why you are reading this book), you might be wondering whether wardriving is a crime. Of course, those doing the wardriving do not view it as such; however, those of you who own the wireless networks might have a slightly different perception. While doing research, I stumbled across a quote—supposedly from the FBI—that states its position as follows:

Identifying the presence of a wireless network may not be a criminal violation, however, there may be criminal violations if the network is actually accessed including theft of services, interception of communications, misuse of computing resources, up to and including violations of the Federal Computer Fraud and Abuse Statute, Theft of Trade Secrets, and other federal violations.

Therefore, if you deploy a wireless network, you are likely to have someone try to find it, so your security depends on that individual’s understanding that it is his responsibility to ensure that he does not violate any local, state, or federal laws that might pertain to his area. To slightly rephrase: You have gone through all the trouble of purchasing equipment, learning the process, loading the tools, and setting everything up. Your wireless network is not secured, and law enforcement expects the wardriver not to do anything illegal. Are you prepared to leave your network vulnerable to those who do not support this law-abiding scenario? If you are, go back to Chapter 1, “There Be Hackers Here,” and start reading again!

Warspamming

Everyone has received spam or junk mail; it is a plague on the Internet and, frankly, in my mailbox at home. I believe in free speech; however, that freedom does not give you the right to be heard. Fortunately, lawmakers and politicians around the world are beginning to notice our feelings on this matter and developing laws to penalize spammers. These laws might or might not be effective—time will tell. However, it is becoming more difficult for spammers to source their spam from countries beginning to develop these laws. Also organizations list IP addresses of places where spam has originated from, so what is a spammer to do? Many are now sourcing their spam from other countries; this presents all sorts of logistical problems and additional costs to spammers. As a spammer, what if I could drive downtown or hire someone to find an open wireless network, join that network, and send my spam?

Remember the concept of downstream liability discussed in Chapter 5, “Overview of Security Technologies?” It would be simple to find an open wireless network and join it to send spam. The attacker (spammer) could be sitting in a café across the street, and you might never know. Now fast-forward a bit; the spam is sent to thousands of people who report that they received it, and yet another wrinkle—the spam was pornographic in nature. Yes, it can be even worse than that. (Remember, we are not talking about people who have morals—they are driven by other goals and needs.) A quick check reveals your network’s IP address, which is then blacklisted and reported to your ISP—and do not forget about the new antispamming laws. The result is that all outgoing email from your company is blacklisted. How embarrassing when your customers get the bounce message saying that your company is spamming, the ISP shuts off your Internet connection, and law enforcement comes knocking. Also, if you have one of those Internet connections where you are billed by usage, expect a big bill this month.

The truth of the matter in warspamming is that your network did spam others, and although it might have been as a result of an attacker, you are now liable because your wireless network was not properly secured. Who do you think is responsible for that, and are they looking for a new job? Expect to see warspamming increase as it becomes more difficult for spammers to operate. Those who want to do questionable things will always find a way; some will stop as it becomes too difficult, and others will not.

Warspying

A nice follow-up to warspamming is warspying, which is a relatively new phenomenon coming to a wireless video network near you. The most popular method of warspying is using those wireless X10 cameras. X10 is the camera featured in pop-up ads all over the Internet, and they invariably have some gorgeous woman in them. X10 is also a means by which to automate your home, as in a smart house; however, that topic is beyond the scope of this book.

Warspying was first documented in the magazine 2600, an interesting read if you can find the few nuggets of technical worth from the rants it prints. Regardless, it outlined how to make a wireless device that can pick up wireless surveillance systems transmissions. Since then, many people have explored and documented the topic online, and there are now reports of people tapping into all sorts of cameras that are transmitting over a wireless network.

Notice I have completely avoided all discussions of the other nefarious uses into which this could develop. The key is awareness and an understanding of how to protect your network.

This section was rather revealing about how wireless networks are found and, to a lesser degree, what some of the threats are. In addition, a variety of more specific threats are possible. Plus, after an attacker joins a wireless network, you have a host of other problems. The following sections examine these topics in more detail.