2. First Things First

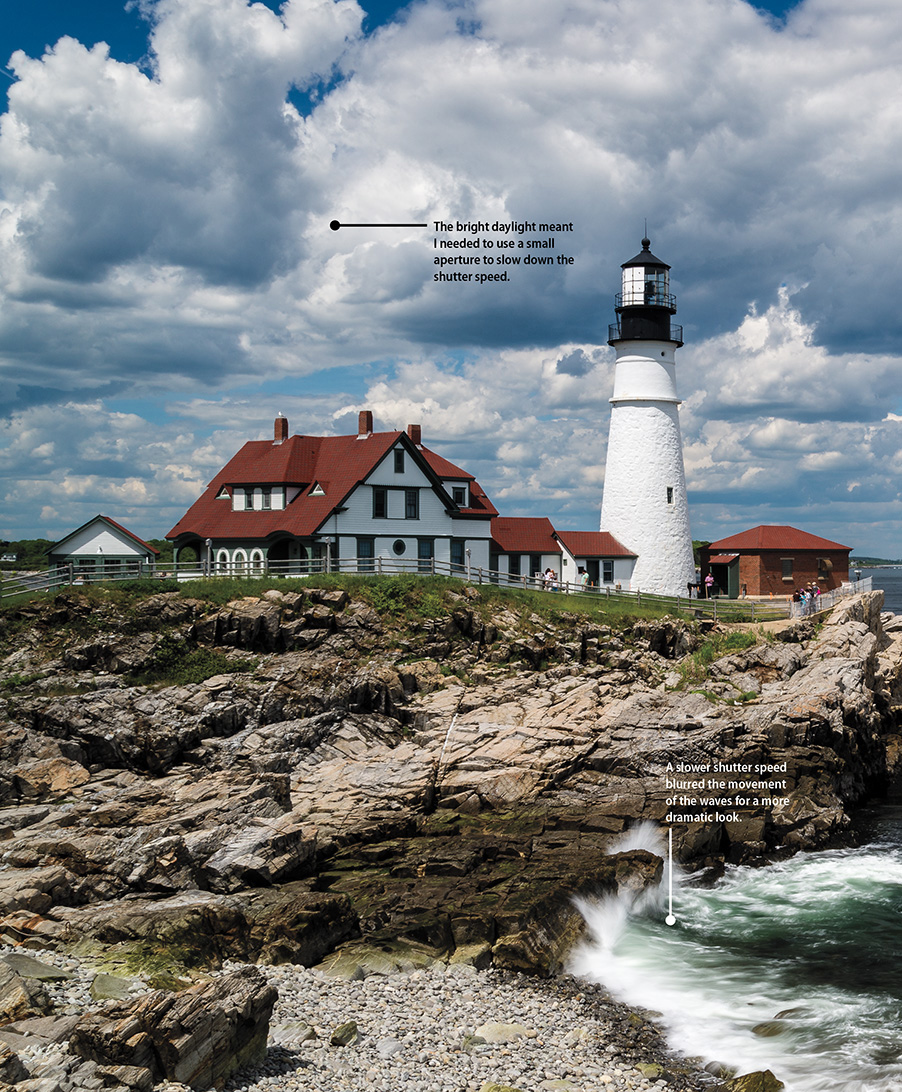

ISO 100 • 1/20 sec. • f/16 • 30mm lens

A Few Things to Know and Do Before You Begin Taking Pictures

Now that we’ve covered the top ten tasks to get you up and shooting, we should probably take care of some other important details. You must become familiar with certain features of your camera before you can take full advantage of it. Additionally, we will take some steps to prepare the camera and memory card for use. So to get things moving, let’s start off with something that you will definitely need before you can take a single picture: a memory card.

I didn’t mean to take this photo. I was leaving my grandmother’s house in Portland, Maine, when I looked up and saw these wonderful puffy white clouds, and my first thought was how awesome for a photograph! Clouds can make or break a landscape photo. Luckily, I wasn’t far from the historic Portland Head Lighthouse, and of course I had my camera with me. Anytime you see clouds like these, it is time to head out and make some photographs.

Choosing the Right Memory Card

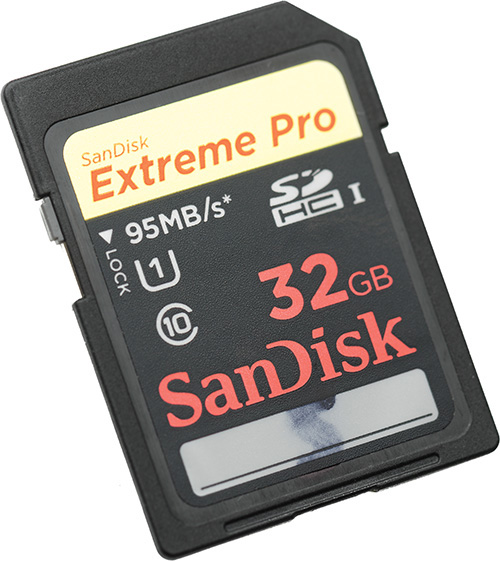

Memory cards are the digital film that stores every shot you take until you move them to a computer. The cards come in all shapes and sizes, and they are critical for capturing all of your photos. It is important not to skimp when it comes to selecting your memory cards. The D750 has two memory slots that accept Secure Digital (SD) memory cards (Figure 2.1).

If you have been using a point-and-shoot camera, chances are that you may already own an SD media card. Which brand of card you use is completely up to you, but here is some advice about choosing your memory card:

• Size matters—at least in memory cards. At 24.3 (effective) megapixels, the D750 will require a lot of storage space, especially if you shoot in raw or the Raw+JPEG mode (more on this later in the chapter). You should definitely consider using a card with a storage capacity of at least 8 GB, if not 16 GB (or more).

• Consider buying High Capacity (SDHC) cards. These cards are generally much faster, both when writing images to the card as well as when transferring them to your computer. If you are planning on shooting video, you can gain a boost in performance just by using an SDHC card with a class rating of at least 6 (I recommend class 10). The higher the class rating of the SD card, the faster the write speed is.

• Buy multiple cards. You can quickly ruin your day of shooting by filling your card and then having to either erase shots or choose a lower-quality image format so that you can keep on shooting. With the cost of memory cards what it is, keeping a few extra on hand just makes good sense.

Formatting Your Memory Card

Now that you have your card, let’s talk about formatting for a minute. When you purchase any new memory card, you can pop it into your camera and start shooting right away—and everything will probably work as it should. However, what you should do first is format the card in the camera. This process allows the camera to set up the card to record images from your camera. Just as a computer hard drive must be formatted, formatting your card ensures that it is properly initialized. The card may work in the camera without first being formatted, but chances of failure down the road are much higher.

As a general practice, I always format new cards or cards that have been used in different cameras. I also reformat cards after I have downloaded my images and want to start a new shooting session. Note that you should always format your card in the camera, not your computer. Using the computer could render the card useless. You should also pay attention to the card manufacturer’s recommendations with respect to moisture, humidity, and proper handling procedures. It sounds a little cliché, but when it comes to protecting your images, every little bit helps.

Most people make the mistake of thinking that the process of formatting the memory card is equivalent to erasing it. Not so. The truth is that when you format the card all you are doing is changing the file management information on the card. Think of it as removing the table of contents from a book and replacing it with a blank page. All of the contents are still there, but you wouldn’t know it by looking at the empty table of contents. The camera will see the card as completely empty, so you won’t be losing any space, even if you have previously filled the card with images. Your camera will simply write the new image data over the previous data.

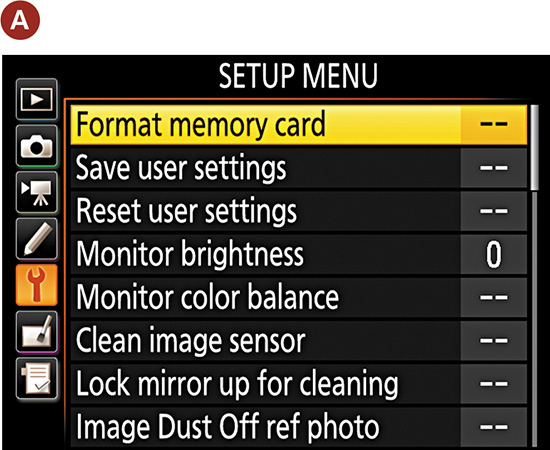

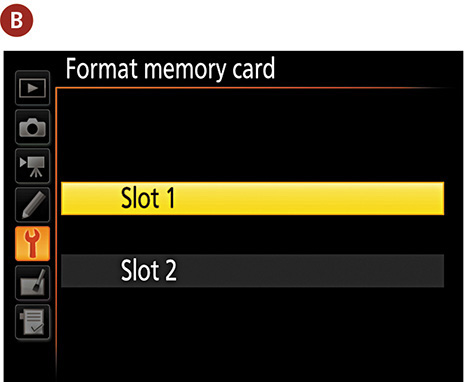

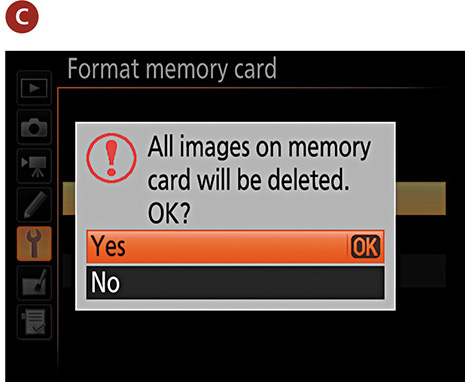

Formatting your memory card

Insert your memory card (or cards) into the camera.

1. Press the Menu button and navigate to the Setup Menu screen.

2. Use the Multi-selector on the back of the camera to highlight the Format memory card option, and press OK (A).

3. Select the memory slot that you want to format, 1 or 2 (B).

4. The next screen will show you a warning, letting you know that formatting the card will delete all images (C). Select Yes and press the OK button.

5. The card is now formatted and ready for use.

Updating the D750’s Firmware

I know that you want to get shooting, but having the proper firmware can affect the way the camera operates. It can fix problems as well as improve operation, so you should probably check it sooner rather than later. Updating your camera’s firmware is something that the manual completely omits, yet it can change the entire behavior of your camera’s operating systems and functions. The firmware of your camera is the set of computer operating instructions that controls how your camera functions. Updating this firmware is a great way to not only fix little bugs but also gain access to new functionality. You will need to go to the Nikon Service & Support page (support.nikonusa.com); then click the link for updating your camera’s firmware to see if a firmware update is available and how it will affect your camera. It is always a good idea to be working with the most up-to-date firmware version available.

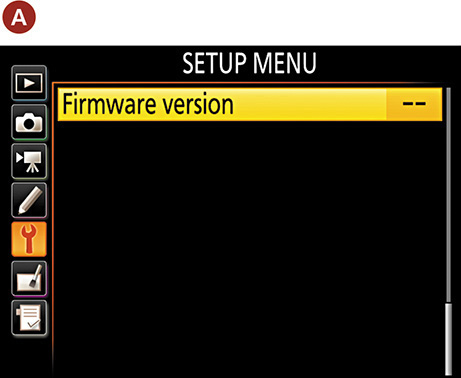

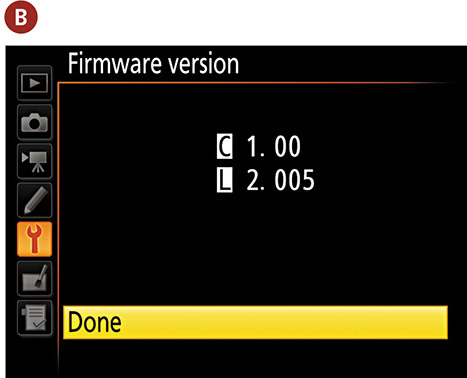

Checking the camera’s current firmware version number

1. Press the Menu button and then navigate to the Setup menu.

2. Use the Multi-selector on the back of the camera to highlight the Firmware version option, and press OK (A).

3. Take note of the current version numbers (there are two of them), and then check the Nikon website to see if you are using the current versions (B).

Updating the firmware from your memory card

1. Download the firmware update file from the Nikon website (support.nikonusa.com).

2. Once you have downloaded the firmware to your computer and extracted it, you will need to transfer it to your memory card. The card must be formatted in your camera prior to loading the firmware to it.

3. With a freshly charged camera battery, insert the card into the camera and turn it on.

4. Follow the instructions listed previously for locating your firmware version, and you will now be able to update your firmware using the files located on the memory card.

As of this writing, there is no firmware update available for the D750. After you check your camera firmware version and the Nikon site for updates, continue to check back periodically to see if any updates become available.

Cleaning the Sensor

Cleaning camera sensors used to be a nerve-racking process that required leaving the sensor exposed to scratching and even more dust. Now cleaning the sensor is pretty much an automatic function. Every time you turn the camera on and off, you can instruct the sensor in the camera to vibrate to remove any dust particles that might have landed on it.

There are five choices for cleaning in the camera setup menu: Clean at startup, Clean at shutdown, Clean at startup and shutdown, Cleaning off, and Clean now. I’m kind of obsessive when it comes to cleaning my sensor, so I like to have it set to clean when I turn the camera on and off.

The one cleaning function that you will need to use via this menu is the Clean now feature. This should be done every time that you remove the lens from the camera body. That’s because removing or changing a lens will leave the camera body open and susceptible to dust sneaking in. If you never change lenses, you shouldn’t have too many dust problems. But the more often you change lenses, the more chances you are giving dust to enter the body. It’s for this reason that I have added the Clean image sensor function to the custom My Menu list (see Chapter 4).

Every now and then, there will just be a dust spot that is impervious to the shaking of the Auto Cleaning feature. This will require manual cleaning of the sensor by raising the mirror and opening the camera shutter. When you activate this feature, it will move everything out of the way, giving you access to the sensor so that you can use a blower or other appropriate cleaning device to remove the stubborn dust speck. The camera will need to be turned off after cleaning to allow the mirror to reset.

If you choose to manually clean your sensor, use a device that has been made to clean sensors (not a cotton swab from your medicine cabinet). There are dozens of commercially available devices—such as brushes, swabs, and blowers—that will clean the sensor without damaging it. If you are not confident in your own ability to clean the sensor, you can always send the camera back to Nikon for cleaning or see if there is a camera store in your area that offers this service. To keep the sensor clean, always store the camera with a body cap or lens attached.

The camera sensor is an electrically charged device. This means that when the camera is turned on, there is a current running through the sensor. This electric current can create static electricity, which will attract small dust particles to the sensor area. For this reason, it is always a good idea to turn off the camera prior to removing a lens. You should also consider having the lens mount facing down when changing lenses so that there is less opportunity for dust to fall into the inner workings of the camera.

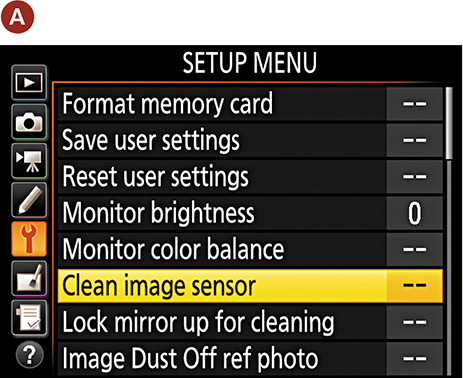

1. Press the Menu button, then navigate to the Setup menu.

2. Use the Multi-selector on the back of the camera to highlight the Clean image sensor option, and press OK (A).

3. Highlight the Clean now option and press the OK button (B). The camera will clean the sensor for about 2 seconds and then return to the menu.

Using the Right Format: Raw vs. JPEG

When shooting with your D750, you have a choice of image formats that your camera will use to store the pictures on the memory card. JPEG is probably the most familiar format to anyone who has been using a digital camera. I touched on this topic briefly in Chapter 1, so you already have a little background on what JPEG and raw files are.

There is nothing wrong with JPEG if you are taking casual shots. JPEG files are ready to use right out of the camera. Why go through the process of adjusting raw images of the kids opening presents when you are just going to email them to Grandma? Also, for journalists and sports photographers who are shooting the maximum frames per second and who need to transmit their images across the wire—again, JPEG is just fine. So what is wrong with JPEG? Absolutely nothing—unless you care about having complete creative control over all your image data (as opposed to what a compression algorithm thinks is important).

As I mentioned in Chapter 1, JPEG is not actually an image format. It is a compression standard, and compression is where things go bad. When you have your camera set to JPEG—whether it is Fine, Normal, or Basic—you are telling the camera to process the image however it sees fit and then throw away enough image data to make it shrink into a smaller space. In doing so, you give up subtle image details that you will never get back in post-processing. That is an awfully simplified statement, but it’s still fairly accurate.

So what does raw have to offer?

First and foremost, raw images are not compressed. Your camera does have a compressed raw format, but it is lossless compression, which means there is no loss of actual image data. Note that raw image files will require you to perform post-processing on your photographs. This is not only necessary—it is the reason that most photographers use it.

Raw images have a greater dynamic range than JPEG-processed images. This means that you can recover image detail in the highlights and shadows that just aren’t available in JPEG-processed images.

There is more color information in a raw image because it is a 12- or 14-bit image (depending on the camera and settings used), which means it contains more color information than a JPEG, which is always an 8-bit image. More color information means more to work with and smoother changes between tones—kind of like the difference between performing surgery with a scalpel as opposed to a butcher’s knife. They’ll both get the job done, but one will do less damage.

Regarding sharpening, a raw image offers more control because you are the one who is applying the sharpening according to the effect you want to achieve. Once again, JPEG processing applies a standard amount of sharpening that you cannot change after the fact. Once it is done, it’s done.

Finally, and most importantly, a raw file is your negative. No matter what you do to it, you won’t change it unless you save your file in a different format. This means that you can come back to that raw file later and try different processing settings to achieve differing results and never harm the original image. By comparison, if you make a change to your JPEG and accidentally save the file, guess what? You have a new original file, and you will never get back to that first image. That alone should make you sit up and take notice.

Advice for new raw shooters

Don’t give up on shooting raw just because it means more work. Hey, if it takes up more space on your card, buy bigger cards or more small ones. Will it take more time to download? Yes, but good things come to those who wait. Don’t worry about needing to purchase expensive software to work with your raw files; you already own a program that will allow you to work with your raw files. Nikon’s ViewNX 2 software comes bundled in the box with your camera and gives you the ability to work directly on the raw files and then output the enhanced results. That said, you will have more control with dedicated raw processing software such as Nikon’s CaptureNX 2 or Adobe’s Photoshop and Lightroom.

My recommendation is to shoot in JPEG mode while you are using this book. This will allow you to quickly review your images and study the effects of the lessons. Once you have become comfortable with all of the camera features, you should switch to shooting in raw mode so that you can start gaining more creative control over your image processing. After all, you took the photograph—shouldn’t you be the one to decide how it looks in the end?

Shooting dual formats

Your camera has the added benefit of being able to write two files for each picture you take, one in raw and one in JPEG. If you have the Raw+JPEG setting selected, your camera will save your images in both formats on your card.

I think shooting Raw+JPEG is actually a good way to transition to shooting raw. You get the ease and safety of the familiar JPEG, and the ability to compare the JPEG against your raw processing experiences. Obviously this will take up more of the space on your memory card and hard drive, but think of it as a stepping-stone on the path to shooting only raw in the future. It took me a little while to make the transition, and looking back there are some shots I took in JPEG mode that I now wish I had a raw version of that I could try to improve. Live and learn.

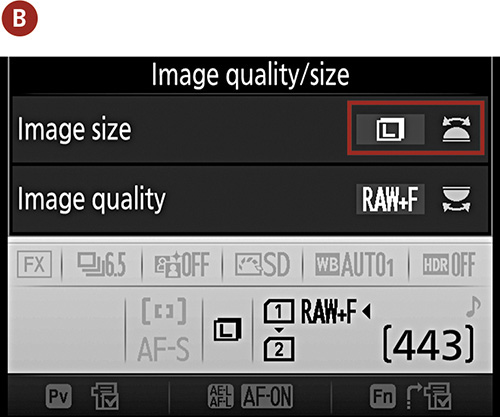

Shooting in raw and JPEG

1. Press and hold the QUAL button.

2. Use the Main Command dial to change the file type to Raw+JPEG.

3. Select one of the three Raw+JPEG settings: Fine, Normal, or Basic (A).

4. Use the Sub-command dial to change the size of the JPEG file (Large, Medium, or Small) (B).

As you change the settings, you should see a change in the number of total images that you can capture before your card is full.

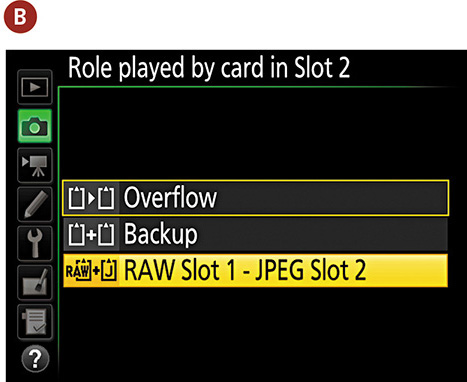

Having two memory card slots is handy for a number of reasons in that you can configure the role of the second card based on your needs. You have three options: Overflow, Backup, and RAW Slot 1 - JPEG Slot 2. For mission-critical work I always choose Backup for the peace of mind of having all photos on two cards simultaneously. When I’m out for more casual shooting I’ll use Overflow, but if you ever have a need to shoot Raw+JPEG and want to keep the JPEGs on their own card, it is nice to have that option, too.

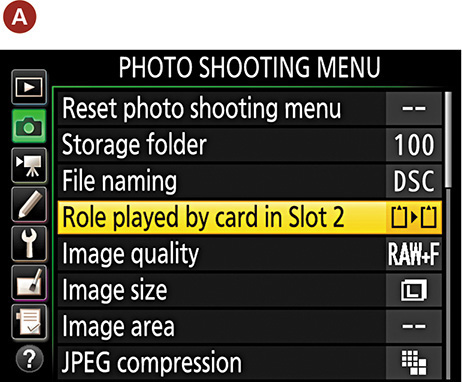

Configure the role of the second card

1. Press the Menu button, then navigate to the Shooting menu.

2. Use the Multi-selector on the back of the camera to highlight the Role played by card in Slot 2 option, and press OK (A).

3. Highlight the option you can want to use, and press OK (B).

Lenses and Focal Lengths

If you ask most professional photographers what they believe to be their most critical piece of photographic equipment, they would undoubtedly tell you that it is their lens. The technology and engineering that goes into your camera is a marvel, but it isn’t worth a darn if it can’t get the light from the outside onto the sensor. The D750, as a digital single lens reflex (DSLR) camera, uses the lens for a multitude of tasks, from focusing on a subject to metering a scene to delivering and focusing the light onto the camera sensor. The lens is also responsible for the amount of the scene that will be captured (the frame). With all of this riding on the lens, let’s take a more in-depth look at the camera’s eye on the world.

Lenses are composed of optical glass that is both concave and convex in shape. The alignment of the glass elements is designed to focus the light coming in from the front of the lens onto the camera sensor. The amount of light that enters the camera is also controlled by the lens, the size of the glass elements, and the aperture mechanism within the lens housing. The quality of the glass used in the lens will also have a direct effect on how well the lens can resolve details and the contrast of the image (the ability to deliver great highlights and shadows). Most lenses now routinely include things like the autofocus motor and, in some cases, a vibration reduction mechanism.

There is one other aspect of the camera lens that is often the first consideration of the photographer: lens length. Lenses are typically divided into three or four groups depending on the field of view they deliver.

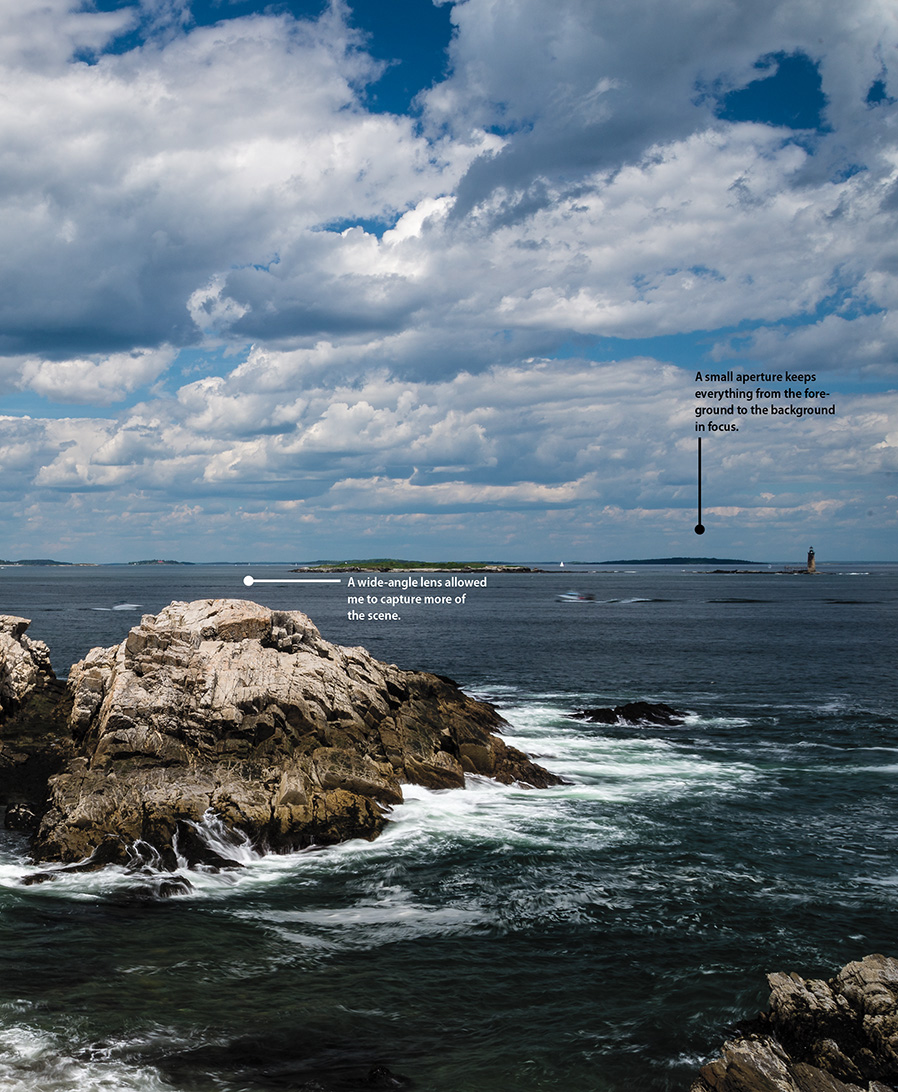

Wide-angle lenses cover a field of view from around 110 degrees to about 60 degrees (Figure 2.2). There is also a tendency to get some distortion in your image when using extremely wide-angle lenses. This will be apparent toward the outer edges of the frame. As for which lenses would be considered wide angle, anything smaller than 50mm could be considered wide.

Figure 2.2 The 24mm lens setting provides a wide view of the scene but little detail of distant objects.

Wide-angle lenses can display a large depth of field, which allows you to keep the foreground and background in sharp focus. This makes them very useful for landscape photography. They also work well in tight spaces, such as indoors, where there isn’t much elbow room available (Figure 2.3). They can also be handy for large group shots but, due to the amount of distortion, not so great for close-up portrait work.

Figure 2.3 When shooting in tight spaces, such as indoors, a nice wide-angle lens helps capture more of the scene.

A normal lens has a field of view that is about 45 degrees and delivers approximately the same view as the human eye. The perspective is very natural and there is little distortion in objects. The normal lens for full-frame digital cameras is the 50mm lens (Figure 2.4).

Figure 2.4 Long considered the “normal” lens for 35mm photography, the 50mm does not offer the same angle as the human eye, but objects seem about the same size in relation to each other.

Normal focal length lenses are useful for photographing people, architecture, and most other general photographic needs. They have very little distortion and offer a moderate range of depth of field (Figure 2.5).

Figure 2.5 The normal lens worked well for this image, which I captured as I walked around a butterfly garden.

Most longer focal length lenses are referred to as telephoto lenses. They can range in length from 135mm up to 800mm or longer and have a field of view that is about 35 degrees or smaller. These lenses have the ability to greatly magnify the scene, allowing you to capture details of distant objects, but the angle of view is greatly reduced (Figure 2.6). You will also find that you can achieve a much narrower depth of field. They also suffer from something called distance compression, which means they make objects at different distances appear to be much closer together than they really are.

Figure 2.6 The telephoto lens allowed me to capture more close-up detail of the distant peak without having to get physically closer.

Telephoto lenses are most useful for sports photography or any application where you just need to get closer to your subject. They can have a compressing effect—making objects look closer together than they actually are (Figure 2.7)—and a very narrow depth of field when shot at their widest apertures.

Figure 2.7 The compressing effect of the long telephoto lens makes the foreground rock, lighthouse, and moon look a lot closer together than they really are.

A zoom lens is a great compromise to carrying a bunch of single focal-length lenses (also referred to as “prime” lenses). They can cover a wide range of focal lengths because of the configuration of their optics. However, because it takes more optical elements to capture a scene at different focal lengths, the light must pass through more glass on its way to the image sensor. The more glass, the lower the quality of the image sharpness. The other sacrifice that is made is in aperture. Zoom lenses typically have smaller maximum apertures than prime lenses, which means they cannot achieve a narrow depth of field or work in lower light levels without the assistance of vibration reduction, a tripod, or higher ISO settings. (We’ll discuss all this in more detail in later chapters.)

Throughout the book, I will occasionally make references to lenses that are wider or more telephoto than the lenses that you may own, because I have a multitude of lenses that I use for my photography. This doesn’t mean that you have to run out and purchase more lenses. It just means that if you do this long enough, you are sure to accumulate additional lenses, which will expand your ability to be even more creative with your photography.

What Is Exposure?

In order for you to get the most out of this book, I need to briefly discuss the principles of exposure. Without this basic knowledge, it will be difficult for you to move forward in improving your photography. Granted, I could write an entire book on exposure and the photographic process—and many people have—but for our purposes I will just cover some of the basics. This will give you the essential tools to make educated decisions in determining how best to photograph a subject.

Exposure is the process whereby the light reflecting off a subject reflects through an opening in the camera lens for a defined period of time onto the camera sensor. The combination of the lens opening, shutter speed, and sensor sensitivity is used to achieve a proper exposure value (EV) for the scene. The EV is the sum of these components necessary to properly expose a scene. A relationship exists between these factors that is sometimes referred to as the “exposure triangle.”

At each point of the triangle lies one of the factors of exposure:

• ISO: Determines the sensitivity of the camera sensor. ISO stands for the International Organization for Standardization, but the acronym is used as a term to describe the sensitivity of the camera sensor to light. The higher the sensitivity, the less light is required for a good exposure. These values are a carryover from the days of traditional color and black and white films.

• Aperture: Also referred to as the f-stop, this determines how much light passes through the lens at once.

• Shutter speed: Controls the length of time that light is allowed to hit the sensor.

Here’s how it works. The camera sensor has a level of sensitivity that is determined by the ISO setting. To get a proper exposure—not too much, not too little—the lens needs to adjust the aperture diaphragm (the size of the lens opening) to control the volume of light entering the camera. Then the shutter is opened for a relatively short period of time to allow the light to hit the sensor long enough for it to record on the sensor.

ISO numbers for the D750 start at 100 and then double in sensitivity as you double the number. So 400 is twice as sensitive as 200. The camera can be set to use 1/2- or 1/3-stop increments, but for ISO just remember that the base numbers double: 200, 400, 800, and so on. There are also a wide variety of shutter speeds that you can use. The speeds on the D750 range from as long as 30 seconds to as short as 1/4000 of a second. Typically, you will be working with a shutter speed range from around 1/30 of a second to about 1/2000, but these numbers will change depending on your circumstances and the effect that you are trying to achieve. The lens apertures will vary slightly depending on which lens you are using. This is because different lenses have different maximum apertures. The typical apertures that are at your disposal are f/4, f/5.6, f/8, f/11, f/16, and f/22.

When it comes to exposure, a change to any one of these factors requires changing one or more of the other two. This is referred to as reciprocal change. If you let more light in the lens by choosing a larger aperture opening, you will need to shorten the amount of time the shutter is open. If the shutter is allowed to stay open for a longer period of time, the aperture needs to be smaller to restrict the amount of light coming in.

How is exposure calculated?

We now know about the exposure triangle—ISO, shutter speed, and aperture—so it’s time to put all three together to see how they relate to one another and how you can change them as needed.

When you point your camera at a scene, the light reflecting off your subject enters the lens and is allowed to pass through to the sensor for a period of time as dictated by the shutter speed. The amount and duration of the light needed for a proper exposure depends on how much light is being reflected and how sensitive the sensor is. To figure this out, your camera utilizes a built-in light meter that looks through the lens and measures the amount of light. That level is then calculated against the sensitivity of the ISO setting, and an exposure value is rendered. Here is the tricky part: there is no single way to achieve a perfect exposure, because the f-stop and shutter speed can be combined in different ways to allow the same amount of exposure. See, I told you it was tricky.

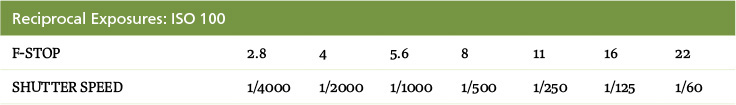

Here is a list of reciprocal settings that would all produce the same exposure result. Let’s use the “sunny 16” rule, which states that when using f/16 on a sunny day, you can use a shutter speed that is roughly equal to the ISO setting to achieve a proper exposure. For simplification purposes, we will use an ISO of 100.

If you were to use any one of these combinations, they would each have the same result in terms of the exposure (i.e., how much light hits the camera’s sensor). Also take note that every time we cut the f-stop in half, we reciprocated by doubling our shutter speed. For those of you wondering why f/8 is half of f/5.6, it’s because those numbers are actually fractions based on the opening of the lens in relation to its focal length. This means that a lot of math goes into figuring out just what the total area of a lens opening is, so you just have to take it on faith that f/8 is half of f/5.6 but twice as much as f/11. A good way to remember which opening is larger is to think of your camera lens as a pipe that controls the flow of water. If you had a pipe that was 1/2” in diameter (f/2) and one that was 1/8” (f/8), which would allow more water to flow through? It would be the 1/2” pipe. The same idea works here with the camera f-stops; f/2 is a larger opening than f/4 or f/8 or f/16.

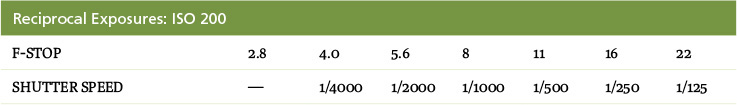

Now that we know this, we can start using this information to make intelligent choices in terms of shutter speed and f-stop. Let’s bring the third element into this by changing our ISO by one stop, from 100 to 200.

Notice that, since we doubled the sensitivity of the sensor, we now require half as much exposure as before. We have also reduced our maximum aperture from f/2.8 to f/4 because the camera can’t use a shutter speed that is faster than 1/4000 of a second.

So why not just use the exposure setting of f/16 at 1/250 of a second? Why bother with all of these reciprocal values when this one setting will give us a properly exposed image? The answer is that the f-stop and shutter speed also control two other important aspects of our image: motion and depth of field.

Motion and Depth of Field

There are distinct characteristics that are related to changes in aperture and shutter speed. Shutter speed controls the length of time the light has to strike the sensor; consequently, it also controls the blurriness (or lack of blurriness) of the image. The less time light has to hit the sensor, the less time your subjects have to move around and become blurry. This can let you control things like freezing the motion of a fast-moving subject (Figure 2.8) or intentionally blurring subjects to give the feel of energy and motion (Figure 2.9).

Figure 2.8 A fast shutter speed was used to freeze the water cascading out of this fountain.

Figure 2.9 The slower shutter speed coupled with a neutral density filter shows the blurred motion of the bus moving up the road.

The aperture controls the amount of light that comes through the lens, but it also determines what areas of the image will be in focus. This is referred to as depth of field, and it is an extremely valuable creative tool. The smaller the opening (the larger the number, such as f/22), the greater the sharpness of objects from near to far (Figure 2.10). A large opening (or small number, like f/2.8) means more blurring of objects that are not at the same distance as the subject you are focusing on (Figure 2.11).

Figure 2.10 Because I used a small aperture, the area of sharp focus extends from a point that is near the camera all the way out to distant objects. In this photo, taken at “the Racetrack” in Death Valley, California, I wanted the rock closest to the camera to be in focus while maintaining good focus into the distance to show how far these mysterious rocks have traveled.

Figure 2.11 Isolating a subject is accomplished by using a large aperture, which produces a narrow area of sharp focus.

As we further explore the features of the camera, we will learn not only how to utilize the elements of exposure to capture properly exposed photographs, but also how we can make adjustments to emphasize our subject. It is the manipulation of these elements—motion and focus—that will take your images to the next level.

An old Pontiac quietly rusts in the back lot of Old Car City.

Chapter 2 Assignments

These assignments focus on helping you get to know your equipment better and ensuring that everything is in tip-top shape before you head out to shoot.

Formatting your card

Even if you have already begun using your camera, make sure you are familiar with formatting the Secure Digital card. If you haven’t done so already, follow the directions given earlier in the chapter and format as prescribed (make sure you save any images that you may have already taken). Then perform the format function every time you have downloaded or saved your images or use a new card.

Checking your firmware version

Using the most up-to-date version of the camera firmware will ensure that your camera is functioning properly. Use the menu to find your current firmware version, and then update as necessary using the steps listed in this chapter.

Cleaning your sensor

You probably noticed the sensor-cleaning message the first time you turned your camera on. Make sure you are familiar with the Clean Now command so you can perform this function every time you change a lens.

Exploring your image formats

I want you to become familiar with all of the camera features before using the raw format, but take a little time to explore the format menu so you can see what options are available to you.

Exploring your lens

If you are using a zoom lens, spend a little time shooting with each focal length, from the widest to the longest. See just how much of an angle you can cover with your widest lens setting. How much magnification will you be able to get from the telephoto setting? Try shooting the same subject with a variety of focal lengths to note the differences in how the subject looks, and also the relationship between the subject and the other elements in the photo.

Share your results with the book’s Flickr group!

Join the group here: www.flickr.com/groups/nikond750_fromsnapshotstogreatshots