3

Extreme Jobs, Extreme Demands

The setting was tranquil enough: an elegant London conference room with celadon carpets, a ming tree, and a misty, romantic view of the River Thames. In sharp contrast, the lives on display at this focus group were hardly serene—or bucolic. Nine corporate executives (seven men, two women) in the thirty-five- to fortyfive-year-old age range were present, all clearly “high potential,” all wrestling with oversized jobs and gargantuan expectations.1

Take Ravi:

I work over a range of time zones, but my main responsibilities are in London and Boston. My “team” is located in both places. That does a number on my evenings. It’s not unusual for it to be midnight and I’m just starting a conference call with my U.S.-based colleagues.

These last six months, with China coming on stream, my days are starting earlier and ending later. I find myself fielding e-mails at 5:30 and 6:00 in the morning. The last thing my wife needs to deal with is me on my BlackBerry before breakfast when I didn’t show up until 11:00 the night before. It’s an issue between us. I’m now unavailable at both ends of the day.

Then there’s Shane:

At least you’re doing something productive when you’re talking to your guys in Boston or China. What sends me nuts here at corporate is the tone at the top. It’s all about jumping through hoops. Here’s what my senior manager likes to do: late on a Friday—it could be 9:00 p.m. or 11:00 p.m., depending on where he is in the world—he sends a two- or three-paragraph e-mail asking me to work on some project. To be honest, these e-mails don’t make a lot of sense. They’re generally full of half-formed ideas and contradictory instructions. But one message is clear. I’m supposed to spend a good chunk of the weekend doing my darnedest to figure out what he wants or needs. And it’s not just me who gets to spend my weekend this way, it’s the support staff too.

So what happens Monday morning? I walk in with all kinds of feedback (facts, figures, analysis, opinion, you name it), and nine times out of ten it’s all irrelevant. I failed to get the assignment quite right.

Does it matter? Not much. It turns out that this exercise is not about what it purports to be about. It’s not about substance, it’s a test. It’s his way of measuring commitment—seeing how high I will jump.

Gwen chimes in:

You guys seem to have complicated challenges. For me, it all comes down to one question—can I grab the 6:30 p.m. to 8:30 p.m. time slot for my kids? I don’t mind going back to work from 9:00 p.m. to 11:00 p.m., but if I can get that earlier window on a regular basis, I’m in good shape. I have three children, and it’s hugely important to me that I’m home a few evenings a week in time to put them to bed. I travel one night a week, on average. I head up a supply chain for the company, and two days a week I have to be somewhere in Europe. The other evenings are precious and I try to protect them. This week I’m beside myself. It’s only Thursday and already two evenings have been shot by business dinners. With our increased global reach, there always seems to be an important customer in town needing to be wined and dined, needing attention.

Ravi’s addendum:

I just want to set the record straight in one regard. I’m obviously dealing with a lot of pressure—and I know I sound stressed out—but I love this job. Riding this wave of expansion in Asia—being part of the reason a country “takes off”—is enormously exciting. Most days, I feel it’s a privilege to do what I do. Add in the fact I’m paid a ton of money to do this job—and you’ve got a pretty alluring package.

Those are just three voices from one of our many focus groups, but enough to afford a glimpse into the escalating tensions, pressures, and rewards of professional life these days. Driven by globalization and facilitated by savvy—and continually improving—communication technology, work pressures are ratcheting up, and jobs, particularly high-level, well-paying jobs, are becoming more and more extreme. As noted by leadership guru Rosabeth Moss Kanter, corporations are increasingly “greedy” institutions and workaholism has become pervasive.2

In the fall of 2005, the Hidden Brain Drain Task Force identified the growth of extreme jobs as a new and urgent challenge facing talented women. American Express, BP, ProLogis, and UBS came on board to fund a research project on this topic, and over a nine-month period (October 2005–June 2006), the task force fielded two surveys and conducted a series of focus groups to investigate the impact of the emerging extreme work model on women’s advancement. What was the trend we suspected we’d find? As work hours and performance pressures ratchet up, women (particularly those with significant caregiving responsibilities) are being left behind in new ways. If an older generation of working mothers had difficulty coping with fifty-hour workweeks, surely their younger peers are having an even more difficult time managing sixty-plus-hour workweeks along with a slew of additional performance pressures.

Before we look at our findings though, it’s important to clarify the components of an extreme job.

OUTSIZE DEMANDS, OUTSIZE RESPONSIBILITIES

I coined the term extreme job four years ago after an interview with a senior banker at a London-based investment bank. Marilyn was enthralled by extreme sports—skydiving, snowboarding, triathlon, bungee jumping, surfing, mountaineering, and the like—anything that provided a rush of adrenalin and a frisson of danger. She urged me to read Jon Krakauer’s Into Thin Air (a book that describes the doomed efforts of a group of amateur mountain climbers who attempted to scale Mount Everest in 1996) to gain a better understanding of why people push themselves to the limits of their physical endurance. Marilyn identified with extreme sports—she felt they spoke to her life as an investment banker. In fact, she admitted, her job and her avocation shared some of the same characteristics. First there were the extraordinary time demands and performance stressors. Seventy-hour workweeks, grueling travel requirements, and relentless bottom-line pressures meant that she was constantly being pushed to the limits of her capacity—both physically and intellectually. Second was the allure of her job. Much like extreme sports, investment banking was exhilarating and seductive, Marilyn told me. “It gives me this adrenalin rush. Like a drug, it’s irresistible and addictive.”3

As Marilyn made clear, an extreme job is characterized by a set of outsize demands. Individuals who hold extreme jobs expend huge amounts of talent, time, energy, skill, and commitment on their jobs. These jobs are as noteworthy for their challenge and intensity as they are for sheer hours spent at work. To get at the complexity of extreme jobs we identified ten key characteristics—or performance pressures—in our early focus group research. These characteristics were then layered on top of workweek and income data. Respondents are considered to have extreme jobs if they are well paid, work sixty hours or more per week, and have at least five of the following extreme job characteristics:

-

Unpredictable flow of work

-

Fast-paced work under tight deadlines

-

Inordinate scope of responsibility that amounts to more than one job

-

Work-related events outside regular work hours

-

Availability to clients 24/7

-

Responsibility for profit and loss

-

Responsibility for mentoring and recruiting

-

Large amount of travel

-

Large number of direct reports

-

Physical presence at workplace at least ten hours a day

With this complex definition our data tells us that a great many highlevel, high-impact jobs these days are “extreme.”4 In our national data survey we find that fully 21 percent of high-echelon workers have extreme jobs. In our global companies survey this figure rises to 45 percent (see figure 3-1). These jobs are no longer limited to Wall Street and the City. Extreme jobs are spreading and are now all over the economy, in large manufacturing companies as well as in medicine and the law; in consulting, accounting, and the media as well as in financial services. They are prevalent on a global scale and are held by fifty-five-year-olds as well as thirty-five-year olds. Extreme jobs are not a young person’s game or a short-term sprint anymore. Rather, they characterize the beginning, middle, and tail end of many careers.5

FIGURE 3-1

Who has an extreme job?

For our analysis one fact is particularly important: extreme workers are predominantly male. Rather few highly qualified women hold extreme jobs. Only 4 percent of women in our national sample of highlevel, high-earning workers hold extreme jobs—a figure that rises to 15 percent in our global companies survey. Within the universe of those that hold extreme jobs, 20 percent are women.

What are the hot-button issues? Which characteristics of extreme jobs generate the most stress and strain for high-echelon workers? And why are these stressors “gendered”—why do they have a differential impact and tend to deal out women? In focus groups and interviews, extreme workers talked graphically about the gargantuan demands of work these days. In particular, they emphasized the long workweeks, the always-on 24/7 culture, and the intense performance pressures.

EXTENDED WORKWEEKS

First, there are the time pressures of extreme jobs. According to our data 56 percent of extreme workers are on the job 70 hours a week or more, 25 percent are on the job more than 80 hours a week and 9 percent are on the job a mind-numbing 100-plus hours a week. Fully 42 percent of people with extreme jobs say they are working an average of 16.6 hours more than five years ago—a stunning finding.

What these hours mean in terms of overload is sobering. Add in a modest 1-hour commute, and a 70-hour workweek translates into leaving the house at 7:00 a.m. and getting home at 8:00 p.m. seven days a week. Such a schedule leaves little time—and little energy—for anything else.6 Sudhir, twenty-three, works as a financial analyst at a major commercial bank in New York. He refers to summer—when he works 90 hours a week, including weekends—as his “light” season. The rest of the year he works upward of 120 hours per week—leaving only 48 hours for sleeping, eating, entertaining, and (he smiles) bathing. Sudhir stays late at the office even when he has nothing specific to do. The face-time culture is one of the hazards of his job—but in Sudhir’s eyes, well worth it: this twenty-three-yearold working his first job takes home $120,000 a year and is among the top 6 percent of earners in America.7

The impact of long workweeks is exacerbated by a paucity of vacation time. Forty-two percent of those with extreme jobs take ten or fewer vacation days per year. And 55 percent regularly cancel vacations because of work pressure.

In one focus group that took place at a Los Angeles–based media company, a forty-eight-year-old executive talked about an amazing recent experience he’d had. For the first time in his fourteen-year career, he’d taken two consecutive weeks of vacation. “It was a revelation,” he said. “I had no idea I even had it in me to enter into this other zone where I was able to focus on my nine-year-old son, and I mean really focus. By the second week I was listening to meandering stories of a tiff he’d had with a best friend and his description of what had happened in the last episode of his favorite TV show, without urging him to get to the point or wrap it up. And we spent hours playing Ping-Pong—a game he loves but I generally have no patience for.” The other focus group participants listened intently, clearly trying to wrap their minds around what a two-week vacation would feel like. The fact is, no one else in the room had ever taken that much time off—at least not in one chunk.8

Rather than being part of a three-to-five-year sprint, long workweeks now seem to persist over the arc of an individual career. It used to be that young professionals would prove themselves by working long hours, but once they had made the cut and moved up the ranks they would be rewarded with more manageable schedules and gentler workdays. But our data shows that long workweeks no longer recede with age: professionals between the ages of thirty-five and forty-five are working longer hours than professionals age twenty-five to thirty-four.

Betty, a fifth-year, newly married associate at a blue-chip law firm, is dismayed by what she sees ahead of her: partners working insanely long hours. Betty regularly bills seventy hours a week—which means she actually puts in closer to eighty to eighty-five hours. Her arduous schedule is becoming problematic—not only because she is thinking of having children but because she sees no prospect of relief. “You work so hard for the brass ring,” she says, explaining what really bothers her, “but getting the brass ring just means you have to work harder. The junior partners at our firm work more hours than the associates. You can no longer look forward to easing up as you go up.”9

Long workweeks—and little vacation—are no longer about breaking into the business; they are the business.

ALWAYS CONNECTED

Overload has, of course, been facilitated by modern communication technology and an always-on 24/7 business culture. The advent of the Internet and its associated hardware (BlackBerrys, Treos, cell phones) has lengthened the working day and blurred the lines between time on the job and off. These “weapons of mass communication” have shifted expectations and behavior. Response time has been reduced from days or weeks to minutes, allowing a 24/7 flow of decision making across sectors, functions, and time zones. We see the result all around us: professionals glued to their cell phones or BlackBerrys, no matter the day, time, location, or occasion.10 In focus groups men and women told anecdotes about how they scrambled to keep up. They pull all-nighters or defy jetlag to attend a meeting in Singapore and immediately return to make a presentation in New York, or they wake up in the middle of the night to participate in global conference calls.11

In our survey 67 percent of people with extreme jobs say that being available for clients all day, every day—in other words, around the clock—is a critical part of being successful at their job.12 Sudhir describes the pressures to stay connected:

Senior people in my industry are very cutthroat and have this belief that everything must be done immediately—at that very instant—even when you’re in a meeting; waiting an hour to respond to an e-mail is just not acceptable. Well, I believe that at the end of the day, this is a financial advisory service. I’m not an ER doctor. Advice can wait. But the senior guys don’t think that way, and in order to get the performance review—and the great bonus—you have to shift your mind-set and think like them. Being on call, every minute, 24/7, is part of the deal. Working weekends is part of the deal. Whatever the client needs or wants is the culture here.

UNPREDICTABLE, ESCALATING PRESSURES

One of the most demanding elements of the always-on 24/7 culture is managing an unpredictable flow of work. In focus groups, executives talked about being constantly sideswiped by deadlines they had not predicted or planned for. One Dallas-based accountant described how, over the previous weekend, her boss had tracked her down at a five-year-old’s birthday party and insisted she join a ninety-minute conference call because something had blown up with a client. A colleague at the same focus group immediately chimed in, explaining how he’d lost all credibility with his wheelchair-bound, elderly father because he’d canceled so many promised weekend visits recently because of work demands.

Finally, extreme jobs often entail intense—and escalating—performance pressures. Again, global competition and modern communication technology are largely, though not solely, to blame. These drivers have contributed to and facilitated a shrinking and flattening of hierarchy—companies and organizations are leaner, and responsibilities are spread across fewer shoulders. Today’s executives often find themselves with dramatically increased and far-flung responsibilities—and very little in the way of support staff to help grease the wheels.

Eighty-two percent of extreme professionals say they must work at a fast pace under tight deadlines simply to do their job. And 66 percent say they don’t have sufficient staffing to manage their work; 71 percent have no dedicated administrative assistant—37 percent don’t even have a shared assistant. All of this contributes to a workload that can spiral out of control—professionals find they ride a razor’s edge that veers between exhilaration and exhaustion.

Alex is a federal prosecutor focusing on securities fraud. He works long hours, typically arrives home at 11:00 p.m., and routinely skips meals. Instead of dinner, he will have a power bar at his desk—or a peanut butter and jelly sandwich when he gets home late at night. He hardly ever makes it home before his two young children are in bed, although he does make a point of taking his oldest to preschool in the morning. He laments that he has made his kids more of a priority than his wife—their time together as a couple is really squeezed—and the occasional “date” seems difficult to manage. On a recent outing with his wife—to a jazz club—Alex found himself falling asleep after just one drink. It’s not hard to imagine why: he averages a seventy-five-hour workweek—but when he’s on trial or preparing for trial the average can rise to ninety-five hours. “I’m just exhausted a lot of the time,” Alex says.13

Nevertheless, he derives enormous satisfaction from his work. A Princeton graduate who majored in urban policy at the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, he has always yearned to give back to the city in which he grew up. He believes his work as a federal prosecutor is enormously worthwhile and he is honored to serve the public in that role. He does, after all, have a hand in enforcing important laws, seeing that justice is served, and helping protect shareholders and employees.

But there’s one real problem with Alex’s great job—its size, he says “makes it undoable. It sometimes seems like we’re painfully understaffed,” Alex explains. “We’re a government agency, and there are severe budget constraints. I always seem to be juggling too many really important cases, asking for an extension here, an adjournment there—and working evenings and weekends. This ‘forever playing catch-up’ is not my preferred way of working but it’s the only way to keep my head above water in this job. Over the last five years I’ve built some great relationships with our FBI agents who often bring me compelling cases—but I can only handle a small proportion of them. It’s disappointing and frustrating, but I just can’t drive myself any harder.”

BADGE OF HONOR

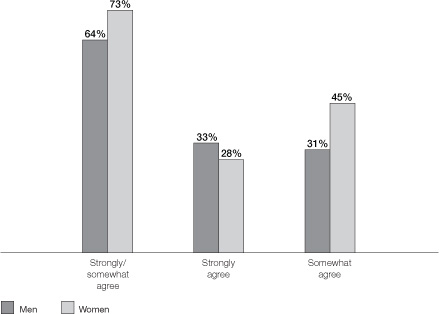

Given the increasingly extreme—and brutal—work model that our data describes, one might imagine that we would have uncovered a great many bitter or burned-out or dissatisfied professionals. Quite the opposite is true. The extreme work model is enormously alluring. Far from resenting the grind, a great many extreme workers adore their jobs. They love the intellectual challenge and the thrill of achieving something big. And they are turned on by their oversize compensation packages, their brilliant colleagues, and the recognition and respect these jobs engender. If extreme jobs have outsize demands they also have outsize rewards. Far from seeing themselves as workaholic drones extreme workers wear their commitments like a badge of honor. There is very little sense of victimization. Two-thirds say that the pressure and the pace are “self-inflicted”—a function of a type A personality. All in all 66 percent of extreme professionals say they love their jobs—and this figure rises to 76 percent in the global companies survey. Nearly 60 percent call their jobs very satisfying—ranking them as 8 or higher on a satisfaction scale of 1 to 10, with 10 being extremely satisfying. Money is an important motivator—especially for men; compensation ranks third for men and fifth for women (see figure 3-2). Only 28 percent of women holding extreme jobs see compensation as a prime motivator, compared with 43 percent of men. For women four other factors weigh more heavily: stimulation, high-quality colleagues, recognition, and status.

FIGURE 3-2

Why extreme workers love their jobs

U.S. survey

Note: multiple responses allowed.

As can be seen from figure 3-3, women are somewhat less likely than men to be completely in love with their extreme jobs. This owes something to the fact that women get fewer payoffs than men from the extreme work model.

GOOD FOR MEN, LESS SO FOR WOMEN

A man in an extreme job is on track to win the triple crown. As psychiatrist Anna Fels points out in her book Necessary Dreams, success at work for men often translates into success in the marriage market and success on the family front. For the male of the species these three things are aligned.14 A man with an extreme job—and an eye-catching compensation package—is seen as extremely eligible. Universally regarded as good husband and father material, he very often gets the girl and the kids. These three dimensions of success are not nearly as aligned for women. Instead, for women, success in an extreme job might well threaten potential mates and get in the way of marriage. These hazards were underscored in a much-talked-about August 2006 opinion piece by Mike Noer in Forbes magazine, which argued that men should think twice before marrying a high-earning career woman because “she is more likely to grow dissatisfied” with her man.15 It seems as though Noer himself is threatened by successful women!

FIGURE 3-3

Men and women love their extreme jobs

U.S. survey

In a similar vein, success in an extreme job may well preempt children for women. A sixty-plus-hour workweek and a variety of other performance pressures are tough things to combine with motherhood in a world where women continue to be the primary caregivers. It’s interesting to note that in the global companies survey 20 percent of women who hold extreme jobs have househusbands. Like Carly Fiorina (whose husband took early retirement), they marry men who are prepared to offer real support at home.

Dessa Bokides, the CFO of ProLogis, has four almost teenage sons—and a stay-at-home husband, Will. He left his career ten years ago to take primary responsibility for their home and children. At the time Bokides had a demanding career on Wall Street and the family was stretched thin. Bokides remembers the moment well: “I had this enormous feeling of relief when Will decided to stay home. Finally I could count on my children being taken care of—not just in terms of their physical care but also in terms of their values and behavior. Having Will at home made it possible for me to do my job.”16

Bokides’s situation is unusual. The survey data shows that men in extreme jobs are much more likely than women in extreme jobs to have the support of an at-home spouse (25 percent versus 12 percent). It’s also true that older men are more likely than younger men to have this kind of support (28 percent versus 21 percent).

TOLL ON PERSONAL LIVES

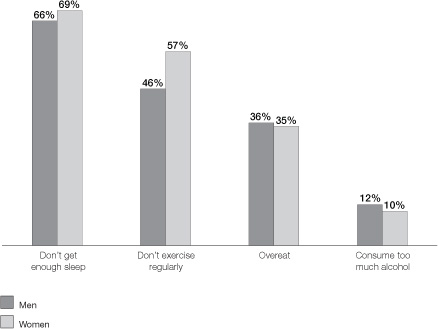

Regardless of gender extreme jobs take a heavy toll on personal lives. Our data shows that the extreme work model is wreaking havoc in private lives—and undermining health and well-being. Much of this fallout has particular significance for women.

Housework and home care seem to be the first things to go. Seventyseven percent of women and 66 percent of men feel they can’t maintain their homes (see figure 3-4). One executive who participated in a Londonbased focus group told us that he had lived in his South Kensington flat for two years but still had no real furniture. A mattress and a sleeping bag were the sum total of his furnishings. His schedule was such that he hadn’t been able to make a commitment to be home to take a delivery.

Health comes next. More than two-thirds of professionals we surveyed don’t get enough sleep, half don’t get enough exercise, and a significant number overeat, consume too much alcohol, or rely on medications to relieve insomnia or anxiety (see figure 3-5).17 The deficit on the exercise front seems to be most acute for women. In focus groups women with extreme jobs—to a much greater extent than their male counterparts—were conscious of the toll these jobs were taking on their bodies.

At one focus group that took place on Wall Street, senior women from the financial sector shared their concerns over weight gain, sleep deficits, and infertility. One thirty-four-year-old investment banker talked about her brutal travel schedule and how she felt it was impacting her fertility. “I’m pretty much commuting to London these days,” she told me. “Sometimes when I fly overnight, deal with back-to-back meetings, then fly home the same day, I’m so deeply exhausted, I wonder what I am doing to myself. My blood pressure’s up and my menstrual cycle is out of whack. Am I depleting my egg supply? This really worries me. I tell you, I’d jump ship for any employer who offered to freeze my eggs.”18

FIGURE 3-4

Fallout on home and intimate life

U.S. survey

Note: multiple responses allowed.

Moms with extreme jobs tend to do better than dads—in terms of coming through for their children. Women with extreme work schedules really fight to find time for their kids, prioritizing them over exercise, for example.19 Men do less well on this front—and pay a price they might not immediately appreciate.

At a focus group at a media company in Los Angeles, John, a forty-fiveyear-old father of two teenagers, decided to hand out some advice. “My biggest regret is that for years I’ve missed dinner with my kids,” he said, looking around at ten colleagues, some of whom were younger men. “If I’m honest, for at least ten, fifteen years, I’ve gotten home in time for dinner barely once a month. It’s only now, when my kids are too old to want it, that I realize what I’ve missed.” The room was silent, and John let out an embarrassed laugh. The emotion was a little raw for a noontime meeting. “So listen up,” he finally said. “Those of you with young kids need to figure out your priorities—now. Thirteen-year-olds, even when they’re good kids, don’t choose to hang around their parents that much.”20

FIGURE 3-5

Fallout on health

U.S. survey

Note: multiple responses allowed.

Spouses and partners also suffer from this work model. Extreme workers dramatically underinvest in intimate relationships. Some of the data is quite startling. For example, at the end of a twelve-plus-hour working day, nearly half (45 percent) of all extreme workers in our global companies survey are too tired to say anything at all to their spouse or partner—they are literally “rendered speechless.” Intimate life is similarly blindsided. Thirty-four percent of extreme workers in our global companies survey are too tired to have sex on a regular basis. Fully half say that their job interferes with a satisfying sex life—and this rises to 55 percent in our global survey. Focus group conversations were sprinkled with half-joking references to four people in bed these days: oneself, one’s partner, and two BlackBerrys. In the words of one recently divorced thirty-two-year-old: “Before we went to bed my ex would put his BlackBerry on vibrate and hide it under the pillow. It used to go off every half hour or so. I felt he was more turned on by his BlackBerry than by me.”21

In her book The Time Bind, sociology professor Arlie Hochschild gets inside the skin of some dual-career couples and describes how home life can become seriously depleted when both husbands and wives work at long-hour jobs.22 She also shows how the situation is cumulative—becoming ever more exaggerated over time. As households and families are starved of time they become progressively less appealing, and both men and women begin to avoid going home. It’s easy to see how returning to a house or an apartment with an empty refrigerator and a neglected teenager might be an unappealing prospect at the end of a long working day. So why not look in on that networking event or put that presentation through one more draft instead? Hochschild shows that for many professionals “home” and “work” have reversed roles: home is where you expect to find stress—and guilt; while work has become the “haven in a heartless world”—the place where you get strokes and respect, a place where success is more predictable.

Singles who work extreme jobs don’t necessarily have it any easier. In focus groups women voiced their frustration with dating—given the constraints of their jobs making any kind of social arrangement was well nigh impossible. The beginning stages of a relationship, when you need to pay attention, need to come through, were seen as particularly difficult. Sharon, a thirty-four-year-old investment banker with an eighty-hour workweek and a bunch of exceedingly demanding clients told of her most recent disaster:

Last night I had a first date with a guy I was really interested in. I was held up by a conference call that dragged on for three hours. So my “date” drove around the block for an hour. Then he parked in a lot, waited another hour, and tried again. At 9:30 p.m. he gave up—just went to eat dinner by himself. I doubt I’ll hear from him again. One thing I’ve started doing is arranging dinners with more than one person. Then if I can’t show no one is left in the lurch. [Sharon laughed ruefully.] But this doesn’t solve my dating problem—the thing is, you can’t have someone dating for you… if I could have some kind of backup out there it would be great.23

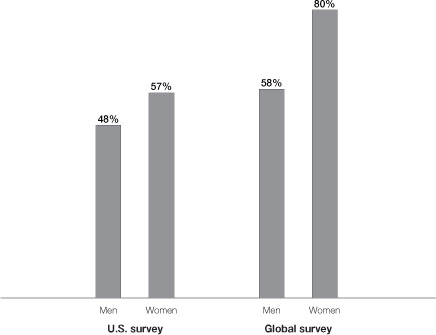

IS THE EXTREME WORK MODEL SUSTAINABLE?

So, are we heading for a cliff? The data is sobering. Both men and women find it difficult to stay with their extreme jobs; 48 percent of men and 57 percent of women don’t want to continue working at this pace and with this intensity for more than a year (see figure 3-6). And only 24 percent (27 percent of men, 13 percent of women) expect to be working at this pace in five years. In our global companies survey these figures rise appreciably. In this data set fully 80 percent of women in extreme jobs don’t want to work that hard for more than year.

Sustainability is perhaps the key challenge in this world of extreme jobs. In focus groups extreme workers talked about feeling as if they were teetering on the edge. On the one hand they continued to be exhilarated by the tremendous challenges of their jobs. On the other hand they were seriously exhausted and increasingly aware of negative spillover in their private lives. They talked about how they couldn’t keep up the pace much longer; of how they had one foot out the door. But while men threaten to leave (yet often stay put), women actually do quit.

FIGURE 3-6

Flight risk and sustainability

Extreme workers planning to work at this pace for one year or less

In explaining why women are willing to walk out on their extreme jobs two factors are particularly important. To begin with, women want relief from their extreme jobs more urgently than men (as mentioned earlier, 57 percent of women versus 48 percent of men don’t want to work this hard for more than twelve months). This desire to opt out (or ramp down) is often related to what is going on with their children. More so than men women are closely tuned in to—and often deeply pained by—negative fallout on their children. The data shows that a large percentage of women connect their extreme job to a range of troubling problems they face with their children. Whether a child is eating too much junk food or underachieving at school, many working moms with extreme jobs feel directly responsible. The data in figure 3-7 offers up a veritable “portrait of guilt.” Maternal anxiety begins to explain why high-powered women are more likely to quit their extreme jobs than are high-powered men.

FIGURE 3-7

Portrait of guilt

Percentage of extreme workers believing their jobs impact children

Global survey

Note: multiple responses allowed.

Women also have more choices than men—a sizable number continue to have options on the work-life front. Data from the national survey tells us that 24 percent of women in extreme jobs have husbands earning more than them, while only 2 percent of men in extreme jobs have wives who outearn them. Quitting an extreme job is easier—and a whole lot less risky—when you have a partner who earns more than you do.

The data also tells us that Gen X and Gen Y “want out” more than baby boomers. In the twenty-five- to thirty-four-year-old age group more than a third (36 percent) of extreme workers say they are likely to quit their job over the next two years. In the forty-five-to-sixty age group this figure drops to 19 percent.

Does all this mean that women are being left behind in new ways?

Our data has already confirmed that extreme workers are predominantly male. The data displayed in quadrant charts A and B (see figures 3-8 and 3-9) show that women are reluctant to take on the long workweeks associated with extreme jobs—only 6 percent of women in our national sample hold jobs with sixty-plus-hour workweeks compared with 29 percent of men. In our global companies survey 18 percent of women hold jobs with sixty-plus-hour workweeks, compared with 36 percent of men. Women are particularly reluctant to take on long-hour jobs if they do not also carry significant responsibilities. Quadrant II in charts A and B are the least favored quadrants for women to be in—only 2 percent of women in our national sample and 3 percent of women in our global companies sample elect jobs that have sixty-plus-hour workweeks but little in the way of other extreme job characteristics (fast pace, tight deadlines, 24/7 client demands, etc.). Men are somewhat more tolerant of long hours/little responsibility jobs. Perhaps women are more discriminating—less tolerant of low-impact work—and more likely to walk away from jobs that involve unproductive face time, because they are more aware of the “opportunity costs” involved in being at work in the first place. Remember our poignant portrait of guilt? Women who trace a direct link between their extreme job and their child underachieving at school may well have a high bar when it comes to assessing the value of their work.

FIGURE 3-8

Quadrant chart A: more hours, fewer women

U.S. survey

Each figure represents 1% of the total population of high earners.

High number of hours = 60+/week

High number of job characteristics = 5+

Quadrant I represents extreme jobholders.

FIGURE 3-9

Quadrant chart B: more hours, fewer women

Global survey

Each figure represents 1% of the total population of high earners.

High number of hours = 60+/week

High number of job characteristics = 5+

Quadrant I represents extreme jobholders.

In a focus group held at Canary Wharf in London a woman lawyer put it succinctly:

When I walk out the door in the morning leaving my two-yearold with the nanny, there’s usually a bit of a scene. Tommy clings, pouts, and whips up the guilt. Now, I know it’s not serious—most of the time he likes his nanny. But it sure makes me think about why I go to work—and why I put in a ten-hour day. It’s as though every day I make the following calculation: do the satisfactions I derive from my job (efficacy, recognition—a sense of stretching my mind) justify leaving Tommy? Some days it’s close run. One thing I do know. It couldn’t be just the money. I need a whole lot of things to be happening for me at work.24

The data generated by our global companies survey contains some rich additional insights on women in extreme jobs. For starters, women seem to be better represented in extreme jobs in large global companies than they are across a range of sectors and occupations in our national sample (32 percent versus 20 percent). Women are also better represented in extreme jobs in North America than they are in Europe and Asia (40 percent versus 23 percent)

REFORMULATING EXTREME JOB PARAMETERS

Heidi Yang, a Hong Kong investment banker in her mid-thirties, illustrates the “edge” some global companies are developing as an employer of choice for young talented women.

Yang is definitely considered a high-potential manager, and she’s on the fast track. During her three and a half years in the investment division of UBS in Hong Kong she’s been promoted twice and now runs a team of twenty-five. When I first interviewed Yang in November 2005 she was pregnant with her first child and trying to figure out how to cope with the immediate future. She described her firm’s parenting leave policy as impressive: she was eligible for fifteen weeks of paid leave in all—which is five weeks more than the Hong Kong statutory ten-week paid maternity leave. She could also add onto the leave any vacation days she had accumulated. In Yang’s view, UBS had every reason to be proud of this policy—it was as generous as any “on the street.” Yang also pointed to two other policies at UBS that had caught her eye: a flexible work option that targets parents, and a short-term, global assignments program that is ideal for working moms. She felt both programs would be useful to her down the road.

Yang’s main worry was that these policies weren’t “for real.” In her words: “I’m fearful that if I take a long maternity leave I won’t be taken seriously ever again. Will taking these options undermine my career? Will they deal me out of the next promotion?”25

A lot was riding on Yang’s ability to balance her extreme job with motherhood from her employer’s point of view as well as her own. UBS—along with most other firms in the financial sector—is attempting to do a much better job of retaining female talent. Yang therefore saw herself as “this huge role model. I sometimes feel that the retention of junior female talent rests on my shoulders.”

The good news is that Yang’s fears were not realized. In a follow-up interview in July 2006 Yang told of taking seventeen weeks of maternity leave, which, in her words, “is extremely long by investment banking standards,” and then going back to work and finding UBS to be surprisingly supportive. “There’s been a real change at this firm,” she says. “The culture is shifting. They’re allowing me to work flexibly—as long as I come through for my clients I can work wherever I want. There’s none of this face time stuff. My bosses seem to understand the importance of keeping women.”26

Kudos to UBS—and other global companies that are beginning to figure out what’s needed in terms of both programs and culture change if they want to retain key female talent. The stakes are high. Our survey data shows that young talented women are particularly well represented in jobs that have moderate hours (forty to sixty hours a week) but high performance requirements (fast pace, tight deadlines, 24/7 client demands, etc.). Our global companies survey shows that fully 39 percent of individuals in these jobs are female (see figure 3-10). This data suggests that women are not afraid of the pressure or the responsibilities of extreme jobs—they just can’t pony up the hours. This fact creates an opportunity for employers. If high-caliber work were “chunked out” differently, if flexible work arrangements were more readily available, companies would have a better shot at tapping into this pool and thus better realize the talents of women who are willing to commit to hard work, pressure, and responsibility but cannot take on the long hours.

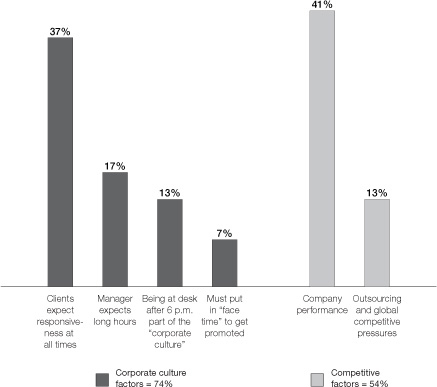

When asked to consider the structural forces that propel the extreme work model, women and men in our survey identified two drivers. First, they pointed to organizational culture. Seventy-four percent of respondents felt that extreme jobs emerge from the value sets and managerial style of a company—or business unit (see figure 3-11). We encountered an example of this at the beginning of this chapter, in our London focus group. When Shane spent his weekend jumping through hoops, he was responding to what he called “tone at the top” in his corporate culture. Second, respondents cited competitive factors emanating from our increasingly “flat” global economy.27

FIGURE 3-10

Targeting high-potential women: young talent, age 25–44

Global survey

Both employers and employees can derive a measure of comfort from this data. If our respondents are correct and extreme jobs are driven more by cultural factors than by economic pressures, it becomes easier to “reengineer” these jobs and create a different and more sustainable work-life model for people who hold them. This would be particularly beneficial to women.

FIGURE 3-11

Drivers of extreme jobs

U.S. survey

Note: multiple responses allowed.

A word on how we categorized the various drivers of extremity. In one of our focus groups a heated discussion erupted as to whether the driver “clients expect responsiveness at all times” belonged in the cultural or the economic category. After an impassioned debate, a consensus emerged: precisely how a business handled responsiveness to clients or customers owed more to tone at the top than any objective business imperative. Executives who had worked in different regional offices of the same multinational firm argued persuasively that expectations on the responsiveness front varied considerably from one regional office to another, and had more to do with managerial style than the corporate bottom line. In some regional offices the value set was crystal clear: the client was king. Whatever the client wanted was done—no matter that the demands placed upon the employee team might be totally unreasonable, including pulling all-nighters or working through the weekend. In these environments, responsiveness was described as “knee-jerk” or “blind.”

In other regional offices the tone at the top was quite different. Here the value set allowed a degree of “push-back.” If a deadline had a little give—and was not tightly linked to the success of a project or a deal—it was OK to negotiate with the client to create a more reasonable time frame. Executives who participated in this focus group were at pains to point out that the flexibility that resulted from this push-back was often minimal—a deadline could be pushed from 9:00 Monday morning to noon—but even those few hours could make a huge difference in terms of salvaging a five-year-old’s birthday party or a weekend visit to dad. One thing these executives were sure of: insisting that the client was king did not necessarily produce great bottom-line results. Some of the more profitable regional offices allowed a considerable degree of push-back. Flexibility did, after all, enhance the ability of the firm to retain valued employees—and what clients disliked most were high turnover rates among the professionals they relied on.

Which brings us to possible solutions. Our survey data tells us that flexible work arrangements are at the heart of the challenge—especially for women. The wish list emanating from extreme workers shows that three out of six of their top picks center on flexibility. For example, 71 percent of women currently working in an extreme job would like a flexible schedule within the framework of a full-time job, 52 percent would like a flexible parttime job, and 61 percent would like “time out” after periods of intensive work (see figure 3-12). Many men also want flexibility—49 percent want paid leave after periods of intensive work—as do 61 percent of women—and 45 percent of men want to work flexibly within a full-time job. Generation X and Y in particular (men as well as women) find these options extremely appealing.28 The data shows that for young men ages twenty-five to forty-four, the ability to work flexibly tops their list of solutions.

Extreme workers are also hungry for other kinds of help from their employers. Exercise facilities, stress reduction classes, restrictions on weekend business travel, and redesigning performance evaluations to de-emphasize face time are all in heavy demand—particularly by women.

FIGURE 3-12

Extreme workers hungry for help

U.S. survey

Note: multiple responses allowed.

In our focus groups the yearning for flexibility came through loud and clear.29 And frankly, some of the most sought-after accommodations seem modest in scope. At the beginning of this chapter, in our London focus group, Gwen spoke eloquently about the importance of being able to spend the 6:30 p.m. to 8:30 p.m. time slot at home. She didn’t mind putting in another two hours late at night but a degree of flexibility in those early evening hours was extremely valuable to her. This was a common refrain among all our survey respondents. One woman in another focus group said she would relocate thousands of miles if an employer would guarantee she could be home for her children’s bedtime.

Unfortunately, many professionals with extreme jobs find it difficult to achieve this kind of flexibility. In many corporate cultures, the early evening hours are particularly demanding. According to one focus group participant who regularly arrived at her office at 6:00 a.m. so that she could put in an eleven-hour day and still be home for dinner: “Employees who are around and available between 6:00 p.m. and 8:00 p.m. get special brownie points. My boss literally checks whose car is still in the parking lot at 7:30 p.m. and I’m sure he notices my car is rarely there. No one checks at 6:30 a.m. Those early hours don’t get you points in this culture.” A colleague of hers who participated in the same focus group volunteered the theory that “it’s some kind of macho screening device. When managers give a lot of weight to those early evening hours it becomes a way of discounting women, of shaking them off.”

Some final thoughts: the ratcheting up of work pressures and the growth and spread of more extreme ways of working have serious consequences for women—and huge implications for the themes of this book. From an individual’s perspective the growth in extreme jobs acts as a drag on a woman’s progress, making it even more difficult for her to rise through the ranks or flourish in a top job. And from an organizational perspective, the growth in extreme jobs seriously hinders a company’s ability to fully utilize its increasingly critical female talent pool. All of which is sobering. It’s as though that male competitive model, far from fading, is morphing and becoming newly robust and vigorous as it feeds off the structural shifts of our age.

The truth is, those of us who are committed to women’s progress on the work front have been battling a moving target. Think of the trajectory of workplace demands over the last thirty years. In the 1970s and 1980s, talented women, armed with impressive educational credentials, moved into professional and managerial positions and began doing well—at least in the early stretches of the career highway. Then, well-paying, highlevel jobs got redefined. Workweeks lengthened and work pressures mounted in ways that made them newly inaccessible to women.

Our data captures trend lines over the last five years, but studies show that for at least twenty years there has been a steady escalation in the number of hours worked—especially among professionals. According to a recent study by economists Peter Kuhn and Fernando Lozano, among college-educated men working full-time, the percentage putting in fiftyhour weeks rose from 22.2 percent in 1980 to 30.5 percent in 2001.30 This structural shift toward more intense and pressurizing ways of working is marginalizing talented women (and men) who have serious hands-on family responsibilities. Judith (whom we met in chapter 1) quit her job not because she failed to produce or perform but because work was encroaching on her life in intolerable ways. That’s not to say that some women don’t rise to the challenge of extreme jobs. Some immensely able superwomen do—especially those who don’t have children. But many highly qualified, committed women don’t. The 60 percent who are my concern in this book are undermined anew by the extreme work model.

I generally don’t go in for conspiracy theories. In this particular case I don’t think for a minute that a bunch of male executives got together in a smoke-filled room and invented a more burdensome work model with the expressed intention of leaving women behind—and shaking off the competition. But I do think that one immensely convenient, unintended consequence of extreme jobs is the way in which they reinforce and perpetuate male hegemony. Convenient, that is, for men.31 But as we’ll see in the next chapter, perpetuating male hegemony is already proving to be extraordinarily shortsighted as a confluence of circumstances constricts the talent pool and makes pursuing diversity the most realistic—and economically sensible—way forward.