Now that we have seen the mechanics of PHP’s object support in some detail, we will step back from the details and consider how best to use the tools that we have encountered. In this chapter, I introduce you to some of the issues surrounding objects and design. I will also look at the UML, a powerful graphical language for describing object-oriented systems.

Design basics: What I mean by design and how object-oriented design differs from procedural code

Class scope: How to decide what to include in a class

Encapsulation: Hiding implementation and data behind a class’s interface

Polymorphism: Using a common supertype to allow the transparent substitution of specialized subtypes at runtime

The UML: Using diagrams to describe object-oriented architectures

Defining Code Design

One sense of code design concerns the definition of a system: the determination of a system’s requirements, scope, and objectives. What does the system need to do? For whom does it need to do it? What are the outputs of the system? Do they meet the stated need? On a lower level, design can be taken to mean the process by which you define the participants of a system and organize their relationships. This chapter is concerned with the second sense: the definition and disposition of classes and objects.

So what is a participant? An object-oriented system is made up of classes. It is important to decide the nature of these players in your system. Classes are made up, in part, of methods; so in defining your classes, you must decide which methods belong together. As you will see, though, classes are often combined in inheritance relationships to conform to common interfaces. It is these interfaces, or types, that should be your first port of call in designing your system.

There are other relationships that you can define for your classes. You can create classes that are composed of other types or that manage lists of other type instances. You can design classes that simply use other objects. The potential for such relationships of composition or use is built into your classes (e.g., through the use of type declarations in method signatures), but the actual object relationships take place at runtime, which can add flexibility to your design. You will see how to model these relationships in this chapter, and we’ll explore them further throughout the book.

As part of the design process, you must decide when an operation should belong to a type and when it should belong to another class used by the type. Everywhere you turn, you are presented with choices, decisions that might lead to clarity and elegance or might mire you in compromise.

In this chapter, I will examine some issues that might influence a few of these choices.

Object-Oriented and Procedural Programming

How does object-oriented design differ from the more traditional procedural code? It is tempting to say that the primary distinction is that object-oriented code has objects in it. This is neither true nor useful. In PHP, you will often find procedural code using objects. You may also come across classes that contain tracts of procedural code. The presence of classes does not guarantee object-oriented design, even in a language such as Java, which forces you to do most things inside a class.

One core difference between object-oriented and procedural code can be found in the way that responsibility is distributed. Procedural code takes the form of a sequential series of commands and function calls. The controlling code tends to take responsibility for handling differing conditions. This top-down control can result in the development of duplications and dependencies across a project. Object-oriented code tries to minimize these dependencies by moving responsibility for handling tasks away from client code and toward the objects in the system.

In this section, I’ll set up a simple problem and then analyze it in terms of both object-oriented and procedural code to illustrate these points. My project is to build a quick tool for reading from and writing to configuration files. In order to maintain focus on the structures of the code, I will omit implementation details in these examples.

The readParams() function parses the same format.

Illustrative code always involves a difficult balancing act. It needs to be clear enough to make its point, which often means sacrificing error checking and fitness for its ostensible purpose. In other words, the example here is really intended to illustrate issues of design and duplication rather than the best way to parse and write file data. For this reason, I omit implementation where it is not relevant to the issue at hand.

As you can see, I have had to use the test for the XML extension in each of the functions. It is this repetition that might cause us problems down the line. If I were to be asked to include yet another parameter format, I would need to remember to keep the readParams() and writeParams() functions in line with one another.

I define the addParam() method to allow the user to add parameters to the protected $params property and getAllParams() to provide access to a copy of the array.

I also create a static getInstance() method that tests the file extension and returns a particular subclass according to the results. Crucially, I define two abstract methods, read() and write(), ensuring that any subclasses will support this interface.

Placing a static method for generating child objects in the parent class is convenient. Such a design decision has its own consequences, however. The ParamHandler type is now essentially limited to working with the concrete classes in this central conditional statement. What happens if you need to handle another format? Of course, if you are the maintainer of ParamHandler, you can always amend the getInstance() method. If you are a client coder, however, changing this library class may not be so easy (in fact, changing it won’t be hard, but you face the prospect of having to reapply your patch every time you reinstall the package that provides it). I will discuss issues of object creation in Chapter 9.

These classes simply provide implementations of the write() and read() methods . Each class will write and read according to the appropriate format.

So, what can we learn from these two approaches?

Responsibility

The controlling code in the procedural example takes responsibility for deciding about format—not once, but twice. The conditional code is tidied away into functions, certainly, but this merely disguises the fact of a single flow, making decisions as it goes. Calls to readParams() and to writeParams() take place in different contexts, so we are forced to repeat the file extension test in each function (or to perform variations on this test).

In the object-oriented version, this choice about file format is made in the static getInstance() method, which tests the file extension only once, serving up the correct subclass. The client code takes no responsibility for implementation. It uses the provided object with no knowledge of, or interest in, the particular subclass it belongs to. It knows only that it is working with a ParamHandler object and that it will support write() and read(). While the procedural code busies itself about details, the object-oriented code works only with an interface, unconcerned about the details of implementation. Because responsibility for implementation lies with the objects and not with the client code, it would be easy to switch in support for new formats transparently.

Cohesion

Cohesion is the extent to which proximate procedures are related to one another. Ideally, you should create components that share a clear responsibility. If your code spreads related routines widely, you will find them harder to maintain as you have to hunt around to make changes.

Our ParamHandler classes collect related procedures into a common context. The methods for working with XML share a context in which they can share data and where changes to one method can easily be reflected in another if necessary (e.g., if you needed to change an XML element name). The ParamHandler classes can therefore be said to have high cohesion.

The procedural example, on the other hand, separates related procedures. The code for working with XML is spread across functions.

Coupling

Tight coupling occurs when discrete parts of a system’s code are tightly bound up with one another so that a change in one part necessitates changes in the others. Tight coupling is by no means unique to procedural code, though the sequential nature of such code makes it prone to the problem.

You can see this kind of coupling in the procedural example. The writeParams() and readParams() functions run the same test on a file extension to determine how they should work with data. Any change in logic you make to one will have to be implemented in the other. If you were to add a new format, for example, you would have to bring the functions into line with one another, so that they both implement a new file extension test in the same way. This problem can only get worse as you add new parameter-related functions.

The object-oriented example decouples the individual subclasses from one another and from the client code. If you were required to add a new parameter format, you could simply create a new subclass, amending a single test in the static getInstance() method.

Orthogonality

The killer combination of components with tightly defined responsibilities that are also independent from the wider system is sometimes referred to as orthogonality . Andrew Hunt and David Thomas discuss this subject in their book, The Pragmatic Programmer, 20th Anniversary Edition (Addison-Wesley, 2019).

Orthogonality, it is argued, promotes reuse in that components can be plugged into new systems without needing any special configuration. Such components will have clear inputs and outputs, independent of any wider context. Orthogonal code makes change easier because the impact of altering an implementation will be localized to the component being altered. Finally, orthogonal code is safer. The effects of bugs should be limited in scope. An error in highly interdependent code can easily cause knock-on effects in the wider system.

There is nothing automatic about loose coupling and high cohesion in a class context. We could, after all, embed our entire procedural example into one misguided class. So how can we achieve this balance in our code? I usually start by considering the classes that should live in my system.

Choosing Your Classes

It can be surprisingly difficult to define the boundaries of your classes, especially as they will evolve with any system that you build.

It can seem straightforward when you are modeling the real world. Object-oriented systems often feature software representations of real things—Person, Invoice, and Shop classes abound. This would seem to suggest that defining a class is a matter of finding the things in your system and then giving them agency through methods. This is not a bad starting point, but it does have its dangers. If you see a class as a noun, a subject for any number of verbs, then you may find it bloating as ongoing development and requirement changes call for it to do more and more things.

Let’s consider the ShopProduct example that we created in Chapter 3. Our system exists to offer products to a customer, so defining a ShopProduct class is an obvious choice. But is that the only decision we need to make? We provide methods such as getTitle() and getPrice() for accessing product data. When we are asked to provide a mechanism for outputting summary information for invoices and delivery notes, it seems to make sense to define a write() method. When the client asks us to provide the product summaries in different formats, we look again at our class. We duly create writeXML() and writeHTML() methods in addition to the write() method. Or we add conditional code to write() to output different formats, according to an option flag.

Either way, the problem here is that the ShopProduct class is now trying to do too much. It is struggling to manage strategies for display, as well as for managing product data.

How should you think about defining classes? The best approach is to think of a class as having a primary responsibility and to make that responsibility as singular and focused as possible. Put the responsibility into words. It has been said that you should be able to describe a class’s responsibility in 25 words or less, rarely using the words “and” or “or.” If your sentence gets too long or mired in clauses, it is probably time to consider defining new classes along the lines of some of the responsibilities you have described.

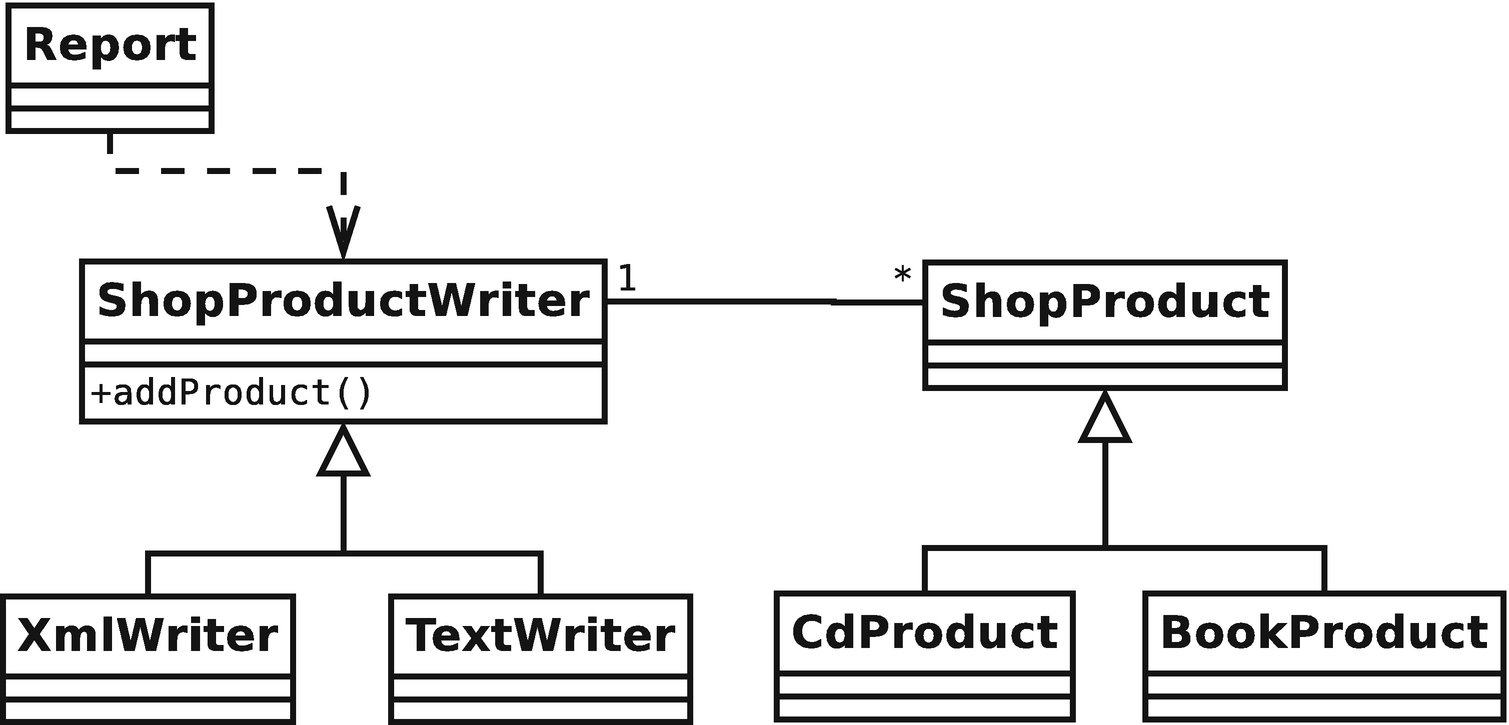

So, ShopProduct classes are responsible for managing product data. If we add methods for writing to different formats, we begin to add a new area of responsibility: product display. As you saw in Chapter 3, we actually defined two types based on these separate responsibilities. The ShopProduct type remained responsible for product data, and the ShopProductWriter type took on responsibility for displaying product information. Individual subclasses refined these responsibilities.

Very few design rules are entirely inflexible. You will sometimes see code for saving object data in an otherwise unrelated class, for example. Although this would seem to violate the rule that a class should have a singular responsibility, it can be the most convenient place for the functionality to live because a method has to have full access to an instance’s fields. Using local methods for persistence can also save us from creating a parallel hierarchy of persistence classes mirroring our savable classes and thereby introducing unavoidable coupling. We deal with other strategies for object persistence in Chapter 12. Avoid religious adherence to design rules; they are not a substitute for analyzing the problem before you. Try to remain alive to the reasoning behind the rule and emphasize that over the rule itself.

Polymorphism

Polymorphism, or class switching, is a common feature of object-oriented systems. You have encountered it several times already in this book.

Polymorphism is the maintenance of multiple implementations behind a common interface. This sounds complicated, but in fact it should be very familiar to you by now. The need for polymorphism is often signaled by the presence of extensive conditional statements in your code.

These statements suggested the shape for the two subclasses: CdProduct and BookProduct.

It is important to note that polymorphism doesn’t banish conditionals. Methods such as ParamHandler::getInstance() will often determine which objects to return based on switch or if statements. These tend to centralize the conditional code into one place, though.

As you have seen, PHP enforces the interfaces defined by abstract classes. This is helpful because we can be sure that a concrete child class will support exactly the same method signatures as those defined by an abstract parent. This includes type declarations and access controls. Client code can, therefore, treat all children of a common superclass interchangeably (as long as it only relies on only functionality defined in the parent).

Encapsulation

Encapsulation simply means the hiding of data and functionality from a client. And once again, it is a key object-oriented concept.

On the simplest level, you encapsulate data by declaring properties private or protected. By hiding a property from client code, you enforce an interface and prevent the accidental corruption of an object’s data.

Polymorphism illustrates another kind of encapsulation. By placing different implementations behind a common interface, you hide these underlying strategies from the client. This means that any changes that are made behind this interface are transparent to the wider system. You can add new classes or change the code in a class without causing errors. The interface is what matters, not the mechanisms working beneath it. The more independent these mechanisms are kept, the less chance that changes or repairs will have a knock-on effect in your projects.

Encapsulation is, in some ways, the key to object-oriented programming. Your objective should be to make each part as independent as possible from its peers. Classes and methods should receive as much information as is necessary to perform their allotted tasks, which should be limited in scope and clearly identified.

Code had to be checked closely, of course, because privacy was not strictly enforced. Interestingly, though, errors were rare because the structure and style of the code made it pretty clear which properties wanted to be left alone.

You may have a very good reason to do this, but, in general, it carries a slightly uncertain odor. By querying the specific subtype in the example, I am setting up a dependency. Although the specifics of the subtype were hidden by polymorphism, it would have been possible to have changed the ShopProduct inheritance hierarchy entirely with no ill effects. This code ends that. Now, if I need to rationalize the CdProduct and BookProduct classes, I may create unexpected side effects in the workWithProducts() method.

There are two lessons to take away from this example. First, encapsulation helps you to create orthogonal code. Second, the extent to which encapsulation is enforceable is beside the point. Encapsulation is a technique that should be observed equally by classes and their clients.

Forget How to Do It

If you are like me, the mention of a problem will set your mind racing, looking for mechanisms that might provide a solution. You might select functions that will address an issue, revisit clever regular expressions, and track down Composer packages. You probably have some pasteable code in an old project that does something somewhat similar. At the design stage, you can profit by setting all that aside for a while. Empty your head of procedures and mechanisms.

Think only about the key participants of your system: the types it will need and their interfaces. Of course, your knowledge of process will inform your thinking. A class that opens a file will need a path, database code will need to manage table names and passwords, and so on. Let the structures and relationships in your code lead you, though. You will find that the implementation falls into place easily behind a well-defined interface. You then have the flexibility to switch out, improve, or extend an implementation should you need to, without affecting the wider system.

In order to emphasize interface, think in terms of abstract base classes or interfaces rather than concrete children. In my parameter-fetching code, for example, the interface is the most important aspect of the design. I want a type that reads and writes name/value pairs. It is this responsibility that is important about the type, not the actual persistence medium or the means of storing and retrieving data. I design the system around the abstract ParamHandler class and only add in the concrete strategies for actually reading and writing parameters later on. In this way, I build both polymorphism and encapsulation into my system from the start. The structure lends itself to class switching.

Having said that, of course, I knew from the start that there would be text and XML implementations of ParamHandler, and there is no question that this influenced my interface. There is always a certain amount of mental juggling to do when designing interfaces.

In Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software (Addison-Wesley Professional, 1995), the Gang of Four summed up this principle with the phrase, “Program to an interface, not an implementation.” It is a good one to add to your coder’s handbook.

Four Signposts

Very few people get it absolutely right at the design stage. Most of us amend our code as requirements change or as we gain a deeper understanding of the nature of the problem we are addressing.

As you amend your code, it can easily drift beyond your control. A method is added here and a new class there, and gradually your system begins to decay. As you have seen already, your code can point the way to its own improvement. These pointers in code are sometimes referred to as code smells—that is, features in code that may suggest particular fixes or at least call you to look again at your design. In this section, I distill some of the points already made into four signs that you should watch out for as you code.

Code Duplication

Duplication is one of the great evils in code. If you get a strange sense of déjà vu as you write a routine, chances are you have a problem.

Take a look at the instances of repetition in your system. Perhaps they belong together. Duplication generally means tight coupling. If you change something fundamental about one routine, will the similar routines need amendment? If this is the case, they probably belong in the same class.

The Class Who Knew Too Much

It can be a pain passing parameters around from method to method. Why not simply reduce the pain by using a global variable? With a global, everyone can get at the data.

Global variables have their place, but they do need to be viewed with some level of suspicion. That’s quite a high level of suspicion, by the way. By using a global variable, or by giving a class any kind of knowledge about its wider domain, you anchor it into its context, making it less reusable and dependent on code beyond its control. Remember, you want to decouple your classes and routines and not create interdependence. Try to limit a class’s knowledge of its context. I will look at some strategies for doing this later in the book.

The Jack of All Trades

Is your class trying to do too many things at once? If so, see if you can list the responsibilities of the class. You may find that one of them will form the basis of a good class itself.

Leaving an overzealous class unchanged can cause particular problems if you create subclasses. Which responsibility are you extending with the subclass? What would you do if you needed a subclass for more than one responsibility? You are likely to end up with too many subclasses or an overreliance on conditional code.

Conditional Statements

You will use if and switch statements with perfectly good reason throughout your projects. Sometimes, though, such structures can be a cry for polymorphism.

If you find that you are testing for certain conditions frequently within a class, especially if you find these tests mirrored across more than one method, this could be a sign that your one class should be two or more. See whether the structure of the conditional code suggests responsibilities that could be expressed in classes. The new classes should implement a shared abstract base class. Chances are that you will then have to work out how to pass the right class to client code. I will cover some patterns for creating objects in Chapter 9.

The UML

So far in this book, I have let the code speak for itself, and I have used short examples to illustrate concepts such as inheritance and polymorphism. This is useful because PHP is a common currency here: it’s a language we have in common, if you have read this far. As our examples grow in size and complexity, though, using code alone to illustrate the broad sweep of design becomes somewhat absurd. It is hard to see an overview in a few lines of code.

UML stands for Unified Modeling Language. The initials are correctly used with the definite article. This isn’t just a unified modeling language, it is the Unified Modeling Language.

Perhaps this magisterial tone derives from the circumstances of the language’s forging. According to Martin Fowler (UML Distilled, Addison-Wesley Professional, 1999), the UML emerged as a standard only after long years of intellectual and bureaucratic sparring among the great and good of the object-oriented design community.

The result of this struggle is a powerful graphical syntax for describing object-oriented systems. We will only scratch the surface in this section, but you will soon find that a little UML (sorry, a little of the UML) goes a long way.

Class diagrams in particular can describe structures and patterns so that their meaning shines through. This luminous clarity is often harder to find in code fragments and bullet points.

Class Diagrams

Although class diagrams are only one aspect of the UML, they are perhaps the most ubiquitous. Because they are particularly useful for describing object-oriented relationships, I will primarily use these in this book.

Representing Classes

A class

The class is divided into three sections, with the name displayed in the first. These dividing lines are optional when we present no more information than the class name. In designing a class diagram, we may find that the level of detail in Figure 6-1 is enough for some classes. We are not obligated to represent every field and method or even every class in a class diagram.

An abstract class

An abstract class defined using a constraint

The {abstract} syntax is an example of a constraint. Constraints are used in class diagrams to describe the way in which specific elements should be used. There is no special structure for the text between the braces; it should simply provide a short clarification of any conditions that may apply to the element.

An interface

Attributes

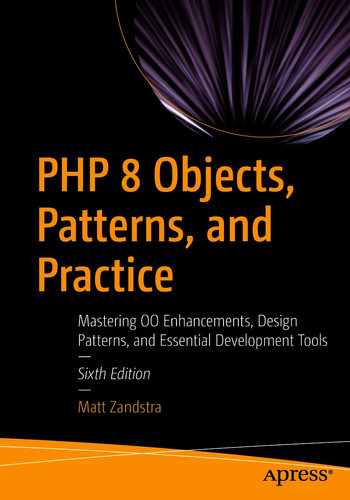

An attribute

Visibility Symbols

Symbol | Visibility | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

+ | Public | Available to all code |

- | Private | Available to the current class only |

# | Protected | Available to the current class and its subclasses only |

The visibility symbol is followed by the name of the attribute. In this case, I am describing the ShopProduct::$price property. A colon is used to separate the attribute name from its type (and optionally, a default value can be supplied at the end, delimited by an equals sign).

Once again, you need only include as much detail as is necessary for clarity.

Operations

Operations

As you can see, operations use a similar syntax to that used by attributes. The visibility symbol precedes the method name. A list of parameters is enclosed in parentheses. The method’s return type, if any, is delineated by a colon. Parameters are separated by commas and follow the attribute syntax, with the attribute name separated from its type by a colon.

As you might expect, this syntax is relatively flexible. You can omit the visibility flag and the return type. Parameters are often represented by their type alone, as the argument name is not usually significant.

Describing Inheritance and Implementation

The UML describes the inheritance relationship as generalization. This relationship is signified by a line leading from the subclass to its parent. The line is tipped with an empty closed arrow.

Describing inheritance

Describing interface implementation

Associations

Inheritance is only one of a number of relationships in an object-oriented system. An association occurs when a class property is declared to hold a reference to an instance (or instances) of another class.

A class association

At this stage, we are vague about the nature of this relationship. We have only specified that a Teacher object will have a reference to one or more Pupil objects, or vice versa. This relationship may or may not be reciprocal.

A unidirectional association

A bidirectional association

Defining multiplicity for an association

Defining multiplicity for an association

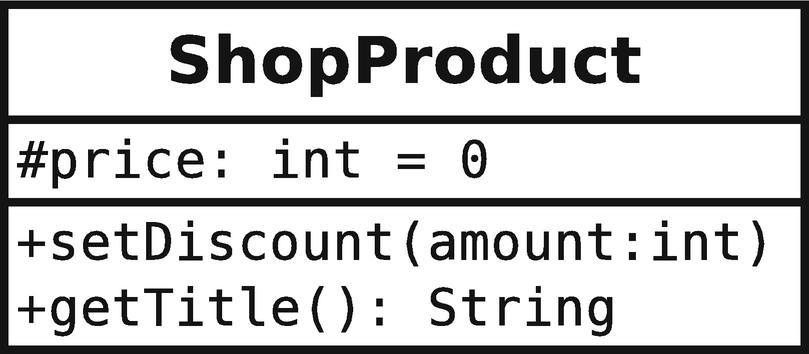

Aggregation and Composition

Aggregation and composition are similar to association. All describe a situation in which a class holds a permanent reference to one or more instances of another. With aggregation and composition, though, the referenced instances form an intrinsic part of the referring object.

In the case of aggregation, the contained objects are a core part of the container, but they can also be contained by other objects at the same time. The aggregation relationship is illustrated by a line that begins with an unfilled diamond.

Aggregation

Pupils make up a class, but the same Pupil object can be referred to by different SchoolClass instances at the same time. If I were to disband a school class, I would not necessarily delete the pupil, who may attend other classes.

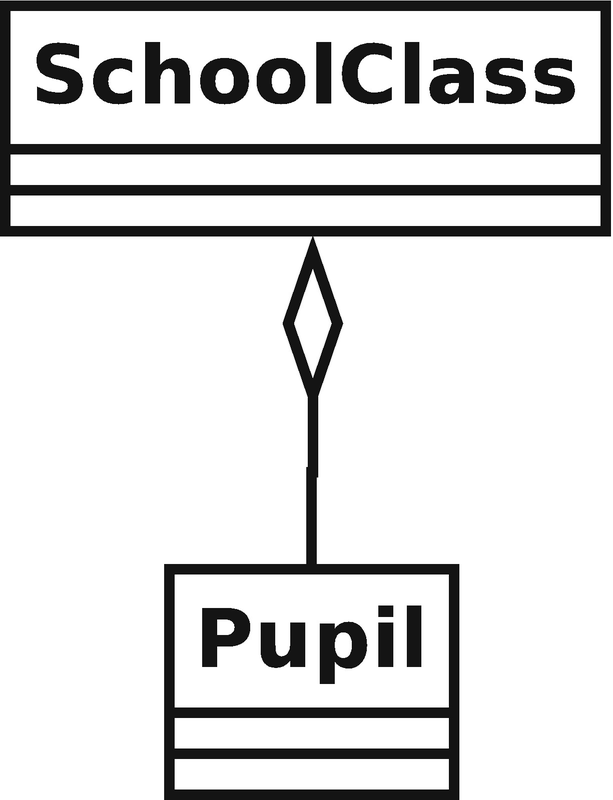

Composition

A Person class maintains a reference to a SocialSecurityData object. The contained instance can belong only to the containing Person object .

Describing Use

The use relationship is described as a dependency in the UML. It is the most transient of the relationships discussed in this section because it does not describe a permanent link between classes.

A used class may be passed as an argument or acquired as a result of a method call.

A dependency relationship

Using Notes

Using a note to clarify a dependency

As you can see, a note consists of a box with a folded corner. It will often contain scraps of pseudo-code.

This clarifies Figure 6-16; you can now see that the Report object uses a ShopProductWriter to output product data. This is hardly a revelation, but use relationships are not always so obvious. In some cases, even a note might not provide enough information. Luckily, you can model the interactions of objects in your system, as well as the structure of your classes.

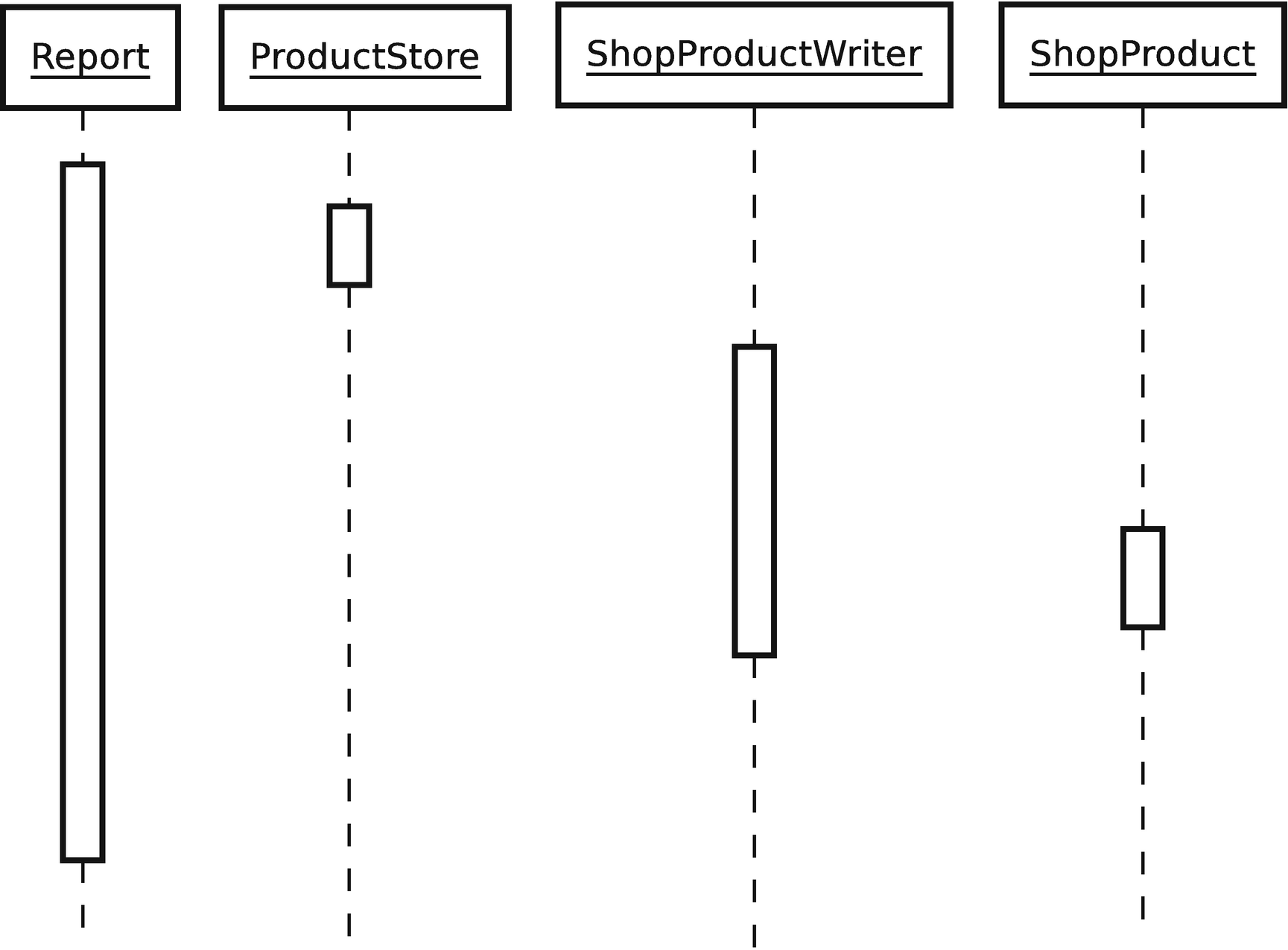

Sequence Diagrams

A sequence diagram is object based rather than class based. It is used to model a process in a system step by step.

Objects in a sequence diagram

I have labeled my objects with class names alone. If I had more than one instance of the same class working independently in my diagram, I would include an object name using the format, label:class (e.g., product1:ShopProduct).

Object lifelines in a sequence diagram

The complete sequence diagram

You can interpret Figure 6-20 from top to bottom. First, a Report object acquires a list of ShopProduct objects from a ProductStore object. It passes these to a ShopProductWriter object, which stores references to them (though we can only infer this from the diagram). The ShopProductWriter object calls ShopProduct::getSummaryLine() for every ShopProduct object it references, adding the result to its output.

As you can see, sequence diagrams can model processes, freezing slices of dynamic interaction and presenting them with surprising clarity.

Look at Figures 6-16 and 6-20. Notice how the class diagram illustrates polymorphism, showing the classes derived from ShopProductWriter and ShopProduct. Now notice how this detail becomes transparent when we model the communication among objects. Where possible, we want objects to work with the most general types available, so that we can hide the details of implementation.

Summary

In this chapter, I went beyond the nuts and bolts of object-oriented programming to look at some key design issues. I examined features such as encapsulation, loose coupling, and cohesion that are essential aspects of a flexible and reusable object-oriented system. I went on to look at the UML, laying groundwork that will be essential in working with patterns later in the book.