Chapter 12

Deciding Roles and Responsibilities

In This Chapter

Seeing how PRINCE2 really helps projects with clear roles and responsibilities

Getting to grips with the PRINCE2 ideas behind project organisation

Meeting the PRINCE2 Project Management Team

Coming to terms with the Project Board, change and assurance roles

Being clear on the Project Manager and Team Manager roles

Understanding Project Support

What the method calls the Project Management Team Structure records the detail of the roles and responsibilities in a PRINCE2 project. You’re probably well aware that many projects get into difficulties because people aren’t clear about what they should do and what other people are doing. This leads to confusion, mistakes, and stuff falling through the gaps. Having clear roles and responsibilities is essential for good project control and PRINCE2 provides that clarity. Actually, it does that rather well.

The even better news is that the method approaches project organisation in a really flexible and practical way. A common misunderstanding when someone gets hold of the manual is for them to look at the organisation diagram and say, ‘Okay, so we need ten or more people – and that’s just for the PRINCE2 stuff.’ In fact, you can adapt the project team structure remarkably simply and quickly for very large projects, very small projects, and absolutely anything in between. Quickly, that is, if you know how, and this chapter shows you how. But all that flexibility hinges on that one important word – roles.

Getting the Right People Involved

Before getting into the detail of organisation, you must be clear on one vital fact. You can have all the methods and approaches you like, but if you involve the wrong people then your project is likely to be in trouble. Equally, involve good people and, even if your approach is not that great, you may well end up with a successful project. Methods such as PRINCE2 are really impressive when you use them well, but the people are more important still.

Philipp Straehl, a highly experienced and successful project manager of large projects, said, ‘Have you got the best people, or the best people available? Big difference’.

Understanding PRINCE2 Management

You need to get to grips with some key elements before drilling down into the detail of individual areas of responsibility. So here they are.

Having roles, not jobs

PRINCE2 describes responsibilities as roles. That isn’t very dramatic, you may think; everyone calls them roles. True, but this is significant for two reasons in the method. The first is to do with people doing more than one thing and the second is to do with status – or actually a lack of status.

Taking on multiple roles and sharing roles

First, a role is not the same as a job because

One person can have more than one role (with a few limitations)

A role can be filled by more than one person (mostly)

A simple example where one person can have more than one role is with a smaller project. You may manage the project as Project Manager but also do some of the specialist work of the project – so you’re also a team member. You manage your own work and possibly the work of others too. If you’ve been wondering why you get paid such a lot, that’s probably the reason.

An example of where more than one person can share a role is in the Project Board – the group of managers with oversight of a PRINCE2 project. One of the roles on the Project Board is Senior User. This is a manager who represents the people who actually use what the project delivers. The Senior User is on the board primarily to make sure that the project delivers the right things – that they’re suitable and usable – and to specify and then deliver the business benefits that result from running the project. Take a project that affects two departments. You may want to have two Senior Users, one from Department A and one from Department B, each to make sure that the deliverables work for their staff. The Senior User role is therefore split across two people; two project ‘jobs’ but sharing one role.

Keeping status out of the equation

The second important aspect of the word ‘role’ is that in PRINCE2 this isn’t about status. Someone very senior in the organisation may have the role of a team member doing some of the work of the project, say checking out the legal policy. Someone much more junior may be the Project Manager. This doesn’t matter, provided that the senior people don’t get awkward about it. If you have to explain this to senior people who don’t like the idea then you can describe the project management as ‘co-ordinating’ their work. If you speak slowly when you explain this to them, even the most senior people are usually able to grasp the point that someone has to co-ordinate things, even if they don’t like the idea of someone ‘managing’ them.

Sticking to small Project Boards

In PRINCE2, Project Boards need to be lean and mean. The minimum number of people on a board is one person, covering all three roles, but the maximum is really no more than about six. The PRINCE2 manual has now retreated in the face of the enemy – those determined to get themselves onto Project Boards! The manual no longer gives the guideline of six as an upper limit and instead just talks about keeping boards as small as possible. But ‘as small as possible’, in some people’s eyes, is a committee of 25 – or more! If you’re under pressure to have more than about six on the board, have a look at Chapter 10, which is about setting up and running successful Project Boards and has some ideas for ways to keep the number down.

If you have a few minutes spare and want some cheap entertainment, do a search for Project Initiation Documents (PIDs) on the Internet and look at the ratio of the number of people on the Project Board to the people actually doing the project work. One I saw had 12 on the board and just 2 on the team doing all the work. To use the old Wild West management joke, ‘Too many chiefs and not enough Indians.’

Seeing the project from three viewpoints

The next aspect of management is powerful. PRINCE2 recognises three key viewpoints in the project: business, user, and supplier.

All three viewpoints are important and you must listen to all three carefully. The business and user interests are from the ‘customer’ side of the project, and the supplier viewpoint is – great surprise – from the supplier side, the people doing the project work. You can trace many project problems back to a lack of involvement of one of these viewpoints.

The business viewpoint

The business viewpoint is primarily ‘value for money’. The project costs a lot and takes significant staff resources. Is it worth it? What will the project deliver and is this worth the cost and the effort involved? This view distils down to the Business Case, which Chapter 11 covers in detail. Although all three of the viewpoints are important, the business viewpoint is the most important of all.

The user viewpoint

The user viewpoint is mostly about the usability of whatever the project is producing, and also for specifying and then delivering the business benefits that will result from the project. The user viewpoint addresses the questions ‘Will it work for our people?’ and ‘Is it fit for purpose?’ Far too many projects deliver things that aren’t what people really want. This can occur for a number of reasons, but a major one is not consulting the users enough. In PRINCE2, one of the users’ own managers is on the Project Board.

The supplier viewpoint

The supplier viewpoint is again concerned about delivery, but in relation to whether the project is workable and the outcome sensible. This viewpoint represents those who work on the project to build the deliverables – in other words, the project teams. Problems crop up where the project does not cover this viewpoint or does not bring it in early enough. If you’ve ever been responsible for work on a project, you may have found yourself saying to managers in a business area: ‘Why didn’t you call us in earlier? You’ve set this up in a really difficult way and there are several ways of doing it that are much easier and better.’

Applying the viewpoints to roles

The three viewpoints are represented very clearly in the Project Board roles (see ‘Viewing the Project Board as central’, later in this chapter), and also in the ‘audit’ areas of Project Assurance.

Recognising a customer/supplier environment

The viewpoints are grouped in two broader categories, as you may have spotted earlier in the chapter. The business and user interests are from the customer side of the project, and the supplier is from the supplier side. The method recognises this customer/supplier environment and manages the potential conflict of interest between the two. If you have an internal supplier for the project, such as your own IT department building the new computer system, then any conflict of interest is small; well, we live in hope anyway.

In recognising this split, PRINCE2 demonstrates that the project is actually the responsibility of the customer; it’s not the supplier’s project. In the world of IT, computer departments have been trying to get the message across for years that the systems don’t belong to the IT department but to the business areas. The IT department is just the supplier that builds and then maintains the system on behalf of the real owner, which is the business area.

Viewing the Project Board as central

The Project Board is the group of senior managers who together own the project. Their place in a PRINCE2 project is extremely important. However, organisations that use the method often misunderstand and completely under-estimate the responsibilities of the board. Chapter 10 covers the effective working of the Project Board and explains the key points where it’s involved in the project. You may understand the function of the Project Board better if you think of it as the Project Manager’s boss.

The Project Board is a group of senior managers, but the word ‘senior’ is relative. On a very small project, for example, the board members may be quite junior in terms of organisational management. Again, the word ‘role’ is significant: As well as putting junior people in ‘senior’ positions, the reverse is true and senior people may hold ‘junior’ positions in the project. Project roles can radically alter the normal management hierarchy and reporting lines.

Keeping the Project Organisation stable

The project organisation must be stable, as far as possible within the limitation of roles. When appointing Project Board members and the Project Manager in particular, you need people who can see the project right through to the end. If you get changes – particularly on the board – during the project, you run the risk of moving goalposts. A new board member taking over part way through the project is likely to say, ‘But I don’t think that the project should be about this at all. What I think is . . .’

A couple of exceptions to this stability are Team Managers, where comings and goings are normal because different work is done on the project, and the Project Board role that represents the supplier viewpoint (see ‘The Senior Supplier(s)’, later in this chapter, for more detail).

Structuring the Organisation of PRINCE2

You document the PRINCE2 roles and how they fit together in the Project Management Team Structure, which you then keep up to date throughout the project.

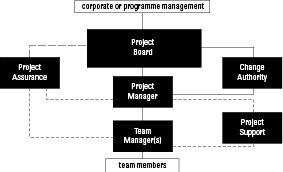

There are four levels of authority in the organisation structure but the first is actually outside the project. Levels 2 to 4 cover the project itself:

1 Corporate or Programme Management: Who the board report to.

2 Project Board: Directing. The board has oversight of the project.

3 Project Manager: Managing. Takes day-to-day responsibility.

4 Team Manager: Delivering. A Team Manager runs a project team.

The roles of Project Board, Project Manager, and Team Manager together with audit (assurance), any change authority and project support (project administration) make up the PRINCE2 Project Management Team, see Figure 12-1. The ‘Project Management Team’ is more than just a label and actually represents a very important PRINCE2 concept.

Figure 12-1: The PRINCE2 Project Management Team.

The PRINCE2 Project Management Team

The word ‘team’ emphasises that the whole group works together to manage the project. Of course you have specialisms within the team, and levels of decision making. But the point remains that everyone on the team is on the same side. If a junior Team Manager has a problem, then potentially everyone has a problem and the whole Project Management Team, right up to Project Board level, may ultimately need to get involved to help solve it.

This PRINCE2 approach of managers working together as a team attacks a common problem in projects. Often, Project Board members somehow think that the project doesn’t have much to do with them. Instead, they delegate the work to the Project Manager and then stay back at a safe distance until the end, when they come back to cut the red ribbon and take the credit if the project works well – or fire the Project Manager if not.

Examining the Project Board

Organisations using PRINCE2 often misunderstand the board responsibilities. To illustrate this area of management, consider a department in an organisation. If you think of the project as a temporary department, then you get the idea. One role, the Executive (representing the ‘business’ viewpoint), is like the department head. Obviously, you have only one head of department and although she listens very carefully to the senior managers in her department, she’s ultimately in charge and makes any necessary decisions if disagreement arises. And, of course, she also takes responsibility for those decisions.

You can think of the two other roles on the board, the Senior User and Senior Supplier (representing the ‘user’ and ‘supplier’ viewpoints), as the senior managers in the department. The head of department values the views of these senior staff and listens very closely to them, bearing in mind their detailed knowledge within their specific areas of responsibility. Normally, this management team in the department agrees on the way to take things forward and reaches decisions by consensus. But in the event of disagreement and when push comes to shove, the head of department makes the decision. In the project and in the Project Board, that’s exactly what the Executive will do. In that sense, the project management of the project is no different to ordinary departmental management in an organisation.

It follows that if the Project Manager is getting conflicting instructions from different board members, she should do what the Executive says.

You can think of the Project Manager as a lower-level manager in the department. The senior staff must have great confidence in that manager; if not, why appoint her to the post? Although the Project Manager doesn’t have ultimate responsibility for the project, she may still have huge amounts of authority and/or responsibility. (Turn to ‘Getting to Know the Project Manager’, later in this chapter, for more on this role.)

Understanding the three Project Board roles

The three roles on the Project Board represent the three key interests of business, user, and supplier.

Executive: The ‘senior’ businessperson, who represents the organisation.

Senior User: A manager who represents those who eventually use whatever the project delivers and who specifies and delivers benefits.

Senior Supplier: A manager who represents the teams that do most of the work on the project.

As well as having oversight, the board is also responsible for providing resources for the project, both the finance and the people. The Executive usually secures the funding, the Senior User provides users to take part in the project, and the Senior Supplier authorises the team hours.

The Executive

The Executive represents the business viewpoint. She’s senior within the organisation, relative to the project, and is responsible for making sure that the project is worth doing. The Executive ‘owns’ the Business Case (please see Chapter 11) and this sums up her interests well. Other board members remain concerned about the value for money of the project, but the Executive particularly focuses on this and takes overall responsibility for it. She analyses the costs of the project (in staff hours as well as capital investment) and the benefits the Senior User is claiming for the project.

The Executive also examines risk: if the benefits are low and the cost is high, the project may still be worth running because the benefits still outweigh the costs. However, if the risks are enormously high, then that may well tip the balance and stop the project running. Equally, a project with fairly low returns, but of negligible risk, may be worth doing.

As well as owning the Business Case, the Executive also has other important responsibilities. A major one is chairing all meetings of the Project Board. This responsibility underlines the point that the business viewpoint is the most important of the three, and that the Executive is ultimately responsible. The Executive is normally the main channel of communication between the project and corporate management and is therefore the person who’ll usually report progress on the project and advise on things such as the levels of benefits expected.

Very importantly, the Executive is also responsible for business assurance, which means checking that the project runs well from a business perspective. The Executive can do this personally, or delegate business assurance to someone else, who does it on her behalf. See ‘Looking at Project Assurance’, later in this chapter, for more on business assurance.

The Senior User(s)

The Senior User is a manager from the user side of the project. The users are those who use what the project delivers – the new headquarters building, the new computer system, or the new business procedure. The Senior User must make sure that the project delivers suitable or fit-for-purpose results. The Senior User role also sets down the benefits of running the project, and then must deliver those benefits. You can have more than one person in the Senior User role.

The Senior User doesn’t spend endless hours talking to designers of the project deliverables: Remember that the Project Board doesn’t do the work of the project. Instead, the Senior User makes sure that the right people in their business area have been talked to, and allocates user resources to make such time available.

Like the Executive, the Senior User role also has responsibility for Project Assurance. The Senior User is responsible for user assurance, which makes sure that the project runs properly from a user viewpoint. (See ‘Looking at Project Assurance’, later in this chapter, for more on user assurance.)

The Senior Supplier(s)

The Senior Supplier is a manager from the supplier side of the project: the teams doing the bulk of the work. The person taking this role must have authority to commit resources to the project and to check that things are being done properly from that supplier perspective.

Choosing the Senior Supplier can sometimes be difficult, but taking the resource issue and turning it around usually pinpoints a suitable person. Just ask yourself, ‘Who will be authorising the team hours for this project?’ That takes you to the right area, and then you can select someone at the right level and with the right authority.

The Senior Supplier is a very important role on the board for a logical reason. The board can’t make meaningful decisions about resources or timing without the Senior Supplier saying that the resources are available. Plans made without supplier input are just wishful thinking. This is also true with suppliers who are from inside the customer organisation. Many a manager has gone to an IT department and said, ‘We need this work done this month,’ only to be told that the IT people are already fully committed on other work for the next six months.

Things can get more complicated in a project with a lot of suppliers – perhaps several internal areas of interest and many outside companies working on the project too. Like the Senior User role, you can have more than one Senior Supplier. You may have one Senior Supplier from the customer organisation who has authority to authorise internal staff resources to the project, and one from the external supplier company who has authority to commit that company’s staff hours. Not only is that split sensible, but you frequently find it’s necessary, because an organisation is unlikely to want to give an outside company authority over its staff or vice versa.

Looking at Project Assurance

PRINCE2 has three types of project audit or Project Assurance within the project that reflect the three key interests of the Project Board:

Business assurance

User assurance

Supplier assurance

To understand Project Assurance think about financial audit and then apply that to the project. In a financial audit, you check that the accounts are accurate and done to the correct standard. This same check applies with the project. Is the project being run properly? Are calculations that the stage is on track actually correct? Are the benefit projections sensible? Are risks being managed properly? Are the teams consulting the right users to make sure that the project delivers the right thing?

Although the Project Management Team structure shows assurance as separate to the Project Board, assurance is actually the responsibility of the Project Board. But board members can delegate the activity of checking to others in two situations: If the project is quite big and the Project Board members simply don’t have the time to do all the checking; or if board members don’t have the skills to do the checking.

Knowing that Project Assurance isn’t optional

The bottom line is that you must do Project Assurance: It’s not optional or negotiable. But unfortunately, Project Assurance is probably the most neglected part of applying PRINCE2: it’s seldom implemented properly, and often not at all.

Deciding how to do Project Assurance

You can set up Project Assurance in four basic ways:

Board members do their own assurance. The Executive does the business assurance, the Senior User does the user assurance, and the Senior Supplier does the supplier assurance.

The board appoints three people (or three teams) to do the assurance work. One team does business assurance and reports back to the Executive, another team does user assurance and reports back to the Senior User, and the last team does supplier assurance and reports back to the . . . you guessed it. You’re really getting the hang of PRINCE2!

The board appoints one person to do all three types of Project Assurance and report back.

The board splits the assurance between board members and dedicated assurance staff. For example, the Executive and Senior User may do their own checking, but someone else does supplier assurance and reports back to the Senior Supplier.

The relationship between financial audit and the finance director is exactly the same. If the financial auditors find problems, you don’t blame the auditors. The responsibility for the organisation’s accounts rests firmly with the finance director. In the same way, the responsibility for the project running properly stays with the Project Board and they can’t delegate that – however much they may want to – either to dedicated Project Assurance staff or the Project Manager.

Working with, and not against, the Project Manager

Some financial auditors are bad auditors. They think that they’re only doing their job well if they cause trouble and find big problems. If these auditors can’t find any big problems, they take some small ones and blow them up out of all proportion. You don’t want that mindset in your Project Assurance staff. Project Assurance and the Project Manager are both on the PRINCE2 Project Management Team and so on the same side. The team should normally work very co-operatively together because they share one objective: to get the project right.

Imagine you do a difficult bit of work and ask an experienced colleague to have a look at it to see whether it looks okay to her. Your colleague picks up a couple of points and you talk them through and clear them up. Then she says, ‘Well, that all looks fine to me.’ Your reaction is to feel very pleased and much more relaxed, because someone you trust checked out your work and gave it the thumbs up. Well, that’s exactly how Project Assurance works. It’s an independent but on-side check – an experienced pair of eyes.

Blowing the whistle

Although Project Assurance aims to be helpful and co-operative, the staff do perform an independent check and are accountable to the Project Board. If the Project Manager hides bad news from the board, then Project Assurance reports that. Project Assurance is like a safety valve on the project that ensures the board get correct information.

Understanding Organisational Assurance

Before leaving the topic of assurance, one more needs a mention. PRINCE2 now calls this Quality Assurance. The name is actually rather misleading as it’s not primarily about the quality of products, which is the normal context of this term, but rather of the whole project. It functions the same way as Project Assurance, except that it’s not done by the Project Board or people that the board members appoint. Instead it’s done from outside the project and is accountable to corporate or programme management. Being independent of the project is quite powerful because it allows checks to be made on the Project Board itself.

If the board members are fairly secure and mature, and not all – no, let’s not climb up on that soapbox! If the board members see the true value of this independent check, they can actually ask for a Quality Assurance check of their project. Taken the right way, such a check is a real confidence boost that things are okay because people who don’t have an axe to grind and who aren’t closely involved have taken a look at the project and checked it out.

Changing Things – Board Authority

It’s normal and usually very sensible to give the Project Manager some authority, time and budget to authorise changes. If the Project Board only authorises what’s on the plans, then even small changes must be referred back to the board because the Project Manager has no authority to do anything about them. So the first question the board faces on change is how much authority it wants to delegate to the Project Manager. Anything more than that then has to be escalated. However, a second decision now has to be made. When the Project Manager does escalate something beyond her authority, should it be to the board or someone else?

The Project Board has an option to set up a Change Authority with an intermediate level of authority between the Project Manager and the Project Board. If the Project Manager wants to escalate a change request, she’d then go to the Change Authority and only if it exceeded that delegated authority would it go to the full Project Board for a decision.

You can find more on change and the options for a Change Authority in Chapter 16. The chapter includes a dire warning of the potential for bureaucracy to sneak in here, with the consequent slowing up of the project. So, you have an incentive to read the chapter – unless you like bureaucracy.

Getting to Know the Project Manager

The Project Manager is responsible for running the project on a day-to-day basis on behalf of the Project Board. You can only ever have one Project Manager in a PRINCE2 project. This may sound a little strange if you’re used to having more than one – for example, a Business Project Manager and a Technical Project Manager – but the rule is there for logical reasons.

A useful analogy for a Project Manager is the captain of a ship. I live in Weymouth on the south coast of the UK, where a high-speed car ferry operates out of Weymouth Harbour to the Channel Islands and St Malo in France. This small ferry has one captain. Now, compare that ferry to a huge passenger vessel like the Queen Mary. Surely, a ship the size of the Queen Mary must have lots of captains on a voyage, probably working shifts and with seven or eight on duty at a time? Absolutely not! No matter how big or small the ship, it only ever has one captain. One person knows what’s going on and has the ‘big picture’. So no matter how big or small the project, you only ever have one Project Manager for the same management reasons.

People who think a PRINCE2 project can have two Project Managers misunderstand PRINCE2 roles. The project may involve specialised areas of work, such as the business area, but Team Managers of the respective teams head these areas up, not multiple Project Managers. The Project Manager is exactly that – the manager of the whole project and not just one bit of it.

You may think that if the board owns the project, the Project Manager has very limited authority and responsibility. But that’s not correct. Going back to the analogy of the Queen Mary passenger liner, does the captain have no authority and no responsibility? Clearly he does. But on that size of vessel the captain doesn’t own the ship, and doesn’t choose the voyage either. In PRINCE2, the Project Board owns the ship and chooses the voyage (the project and the scope); the Project Manager runs the project on a day-to-day basis and perhaps has very substantial authority to do so.

Considering Team Manager(s)

The teams are those people doing the work of the project and in PRINCE2 each team has a Team Manager. The Team Manager is the only role in the main organisational structure that’s optional. On a very small, one-team project, the Project Manager may also manage the team. Most projects have more than one team, however, and some have many.

Teams can come from inside the customer organisation and from outside suppliers. Either way, they’re project teams and are under the control of the Project Manager. In other words, although some teams may be from outside the customer organisation, they’re nevertheless inside the project. This is quite an important point in PRINCE2 project and stage planning; Chapter 14 tells you more about planning and ‘internal’ and ‘external’ deliverables.

Knowing How Project Support Helps

Project Support is mostly an administration service for Project and Team Managers. Think of a good personal assistant (PA) and translate that into a project environment, and then you get the idea. Project Support is a person or people who are excellent administrators, but who also understand projects and PRINCE2.

Some argue that Project Support is also an optional role, but don’t listen – there’ll always be some administration work, even if the person who is the Project Manager does it herself. Often, this admin work falls to the Project Manager by default, and nobody really thinks about it. But if you accept that Project Support is a mandatory role, then adding it to the load of the person who is also the Project Manager is a conscious decision, albeit fully justified for a particular project.

In most cases, the Project Manager spending a large chunk of her time doing administrative work doesn’t make sense. Getting someone else to do the administration – often at lower cost, faster, and better – is much more practical, and this frees up the Project Manager to concentrate on running the project, or perhaps more than one. But flexibility is always the order of the day in PRINCE2, so exceptions include the following scenarios:

The project is geographically distant from where administrators are based and communications are problematic (not just physically, but in terms of the potential for misunderstanding too)

The admin load is light and having the Project Manager do it is simpler and more convenient

The Project Manager can be full-time on the project and can concentrate on it, rather than part-time and having to do non-project work as well

The organisation has money to burn and insists on doing administration as expensively and inefficiently as possible

Many organisations seem to be very committed to the last of these scenarios. Interestingly, though, most of those organisations don’t apply the same principle to their top organisational managers, who all have PAs or secretaries.

Setting up a Project Office

In larger organisations centralising the support function with a Project Office can be very effective. Project Offices can be excellent, or extremely bad – much depends on how organisations set them up.

If you set up an office with good staff who understand their role (support) and take professional pride in that, the Project Office can be stunningly good. It can actually take on a greater role than just administrative support and offer advice to Project and Team Managers in areas such as planning and risk management. In that way, Project Offices can act like an internal project consultancy unit.

Where Project Offices tend to go wrong is where the staff involved aren’t content to support and want to control the projects. Then the office gets involved in monitoring and even enforcing standards. This confuses the role of support with assurance and is bad news indeed. In some cases, Project Offices have taken over so completely that they even bypass Project Managers and Project Boards and report on project progress – with beautifully standardised reports – directly to corporate management. This causes all sorts of problems, and if you translate this situation back to organisational management you can immediately see why: Imagine some small unit in a department telling more senior managers how to do their jobs and then reporting direct to the management board, bypassing not only those managers but also the department’s own top managers and head of department. This locks back to the warning earlier in the chapter on not allowing Project Offices to get involved with Quality Assurance; the external auditing of projects.