Mass Production

New mass-production and distribution methods, along with new packaging materials, changed the way food was integrated into people's lives. In 1899, wax-seal packaging, invented by Henry G. Eckstein, gave manufacturers the ability to more widely distribute fresh, perishable goods. These advances in packaging technology made staples like flour and meat more readily available. Hermetically sealed containers, which offered consumers shelf-stable food products, were another major development. The use of tin cans to seal cooked food made possible a yearround supply of foods that previously had been available only seasonally.

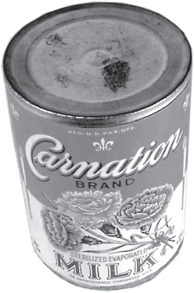

Fig. 1.18

Carnation condensed milk.

All the products that used these new inventions were advertised through the packaging design. This marked the beginning of the use of packaging design to communicate technological innovation and product developments (figs. 1.18 through 1.22).

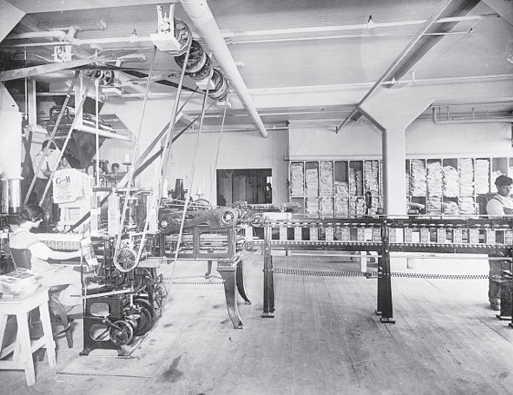

Fig. 1.19

Carton machine, circa 1910. This machine—which folded, glued, filled, weighed, and sealed thirty 2-pound or 5-pound cartons per minute and required only one operator—was revolutionary for its time.

The U.S. Congress, struggling with how to manage a free-market system and still protect consumers, passed the Pure Food and Drug Act in 1906. It was the first set of regulations imposed on packaging design. Although the law prohibited the use of false or misleading labeling, it did not require an accurate statement of ingredients, weight, or measure. Its mandate was, therefore, difficult to enforce.

With the occasional sale of inferior or impure goods making them wary, product protection became increasingly important to consumers. Honest merchants marked their goods with their own identification, both for consumer protection and as a way to build brand awareness. Aluminum foil, which was developed when the first aluminum manufacturing plant opened in Switzerland in 1910, made it possible to effectively seal medications and other air-sensitive products such as tobacco and chocolate.

Fig. 1.20

Waiter holding a bottle of Budweiser beer on a tray, circa 1908.

Fig. 1.21

Making up butter in pound packages, circa 1910.

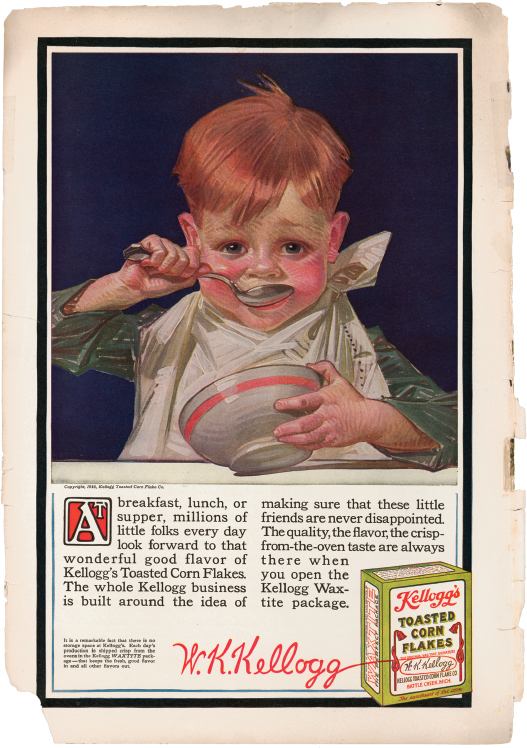

Fig. 1.22

Ad for Kellogg's Waxtite Toasted Corn Flakes, Ladies Home Journal, April 1916. Kellogg's used paperboard cartons to hold flaked corn cereal. A heat-sealed bag of Waxtite was initially wrapped around the outside of the box and printed with the brand name and product information. Later, the waxed bag was moved inside the carton.

The marketing of cereal through paperboard packaging reveals Kellogg's keen understanding of its brand's strength through the marriage of the structural and visual elements of the packaging design.

With the assembly line instituted by Henry Ford in 1913, mass production took off in the United States and soon included the food industry. A number of technical innovations led to the continued improvement of packaging and, consequently, to expanded food choices, thereby improving the standard of living—and increasing the demand on the design of its packaging. Manufacturers needed to address the concerns of consumers leery of paying for the packaging rather than the actual product. Many manufacturers had their printers design labels with a price, so consumers could see that they were not paying for the weight of the packaging materials or a marketer's surcharge. Labels for tea packets were among the first to include weights and prices along with product information.

In 1913, the Gould Amendment to the Pure Food and Drug Act required labeling to state the net quantity of a package's contents, either by weight, measure, or numerical count. This act did little to protect consumers, however, since many took no notice of this statement and continued to purchase products based on the size and shape of the package. This led Supreme Court Justice Louis D. Brandeis to apply the term caveat emptor, or “buyer beware.”

By the early twentieth-century, the dependence of manufactured products on packaging materials and design had become complete: to the consumer, the product and the packaging were perceived as one and the same. Matches could not be sold without a matchbox. Dry goods were boxed through proper and affordable filling and storage methods. Canned goods provided safely preserved foods and consumer convenience (figs. 1.23 through 1.31).

In 1920, Clarence Birdseye, the father of frozen food, invented a system for flash-freezing fresh food. The process safely preserved the taste and appearance of food, which was then packed in waxed cartons. (The practice of preserving food by freezing can, however, be traced back to the early seventeenth century; the first time a business produced frozen food was late in the same century.)

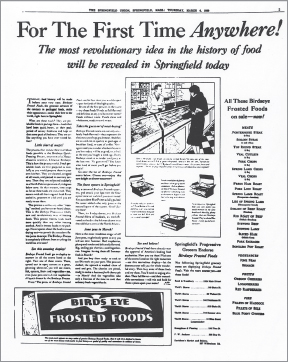

Fig. 1.23

Birds Eye Frosted Foods advertisement, circa 1930.

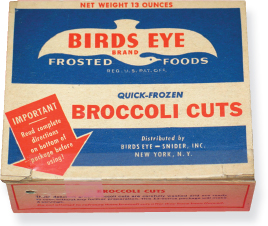

Fig. 1.24

Birds Eye Frosted Foods box, circa 1930.

Fig. 1.25

G. W. Armstrong drugstore, circa 1913.

Fig. 1.26

Sunday shoppers on New York City's Lower East Side, circa 1915.

Fig. 1.27

Interior view of a Piggly Wiggly self-service grocery store, circa 1917.

Fig. 1.28

Bottles of shampoo and lotions manufactured by the C. L. Hamilton Co. of Washington, DC, circa 1909–1932.

Fig. 1.29

Woman shopping for canned goods at a Chicago grocery store, 1920s.

Industrial plastics development began in the mid-1800s, with celluloid material used for photographic film. But the invention of cellophane in the early 1920s marked the beginning of the era of plastics. Every decade since has seen the introduction of new plastic materials. Plastic, in all of its forms and formulations, became one of the most widely used materials for product packaging.

Post–World War I America was marked by several decades of urbanization and industrialization—and an increase in the availability of massproduced merchandise. The 1920s brought an advertising boom as companies responded to postwar consumerism. New products, introduced at an accelerated rate, created demand and forced leading manufacturers to invent new ways of selling them. Products needed to look good, distinguish themselves from one another, and reflect the ever-changing values of the consumer if they were to sell. Marketing became a priority, and the business of packaging design developed as an important strategy for consumer products companies (figs. 1.32 and 1.33).

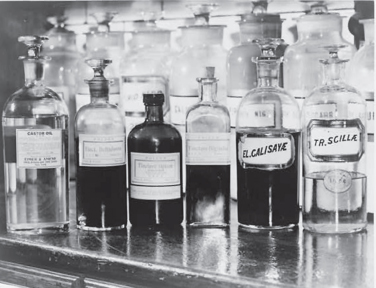

Fig. 1.30

Apothecary bottles.

A display of several apothecary bottles containing drugs, on the shelf of the Eimer and Amind Drugstore, 1940.

By the early 1930s, packaging design was blossoming into a mature industry. The American middle class constituted a growing consumer base, and women, as the decision makers for most household purchases, began to play a greater role in the economy. Marketers competing for their attention sought new ways to attract them to the marketplace.

Fig. 1.31

Arm & Hammer Brand Soda.

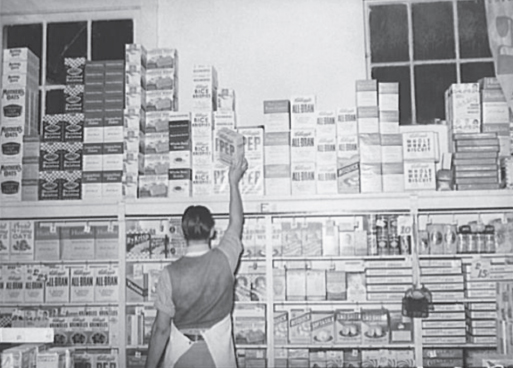

Fig. 1.32

Placing packaged goods on a display shelf, circa 1939.

Fig. 1.33

Woman speaking to Congress about the misleading packaging of tea and tomato juice, circa 1939.

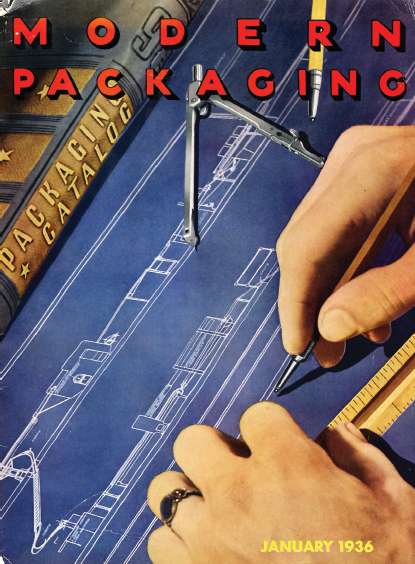

A variety of publications provided suppliers, designers, and clients with the latest information in the field. Advertising Age devoted attention to packaging design, as did industry-specific magazines such as American Druggist, the Tea and Coffee Trade Journal, and Progressive Grocer. The publication of magazines such as Modern Packaging and Packaging Record signaled the complexity of this growing profession and the collaboration of consumer product companies with packaging design and advertising leaders, packaging materials manufacturers, printers, and others in production roles (fig. 1.34).