Chapter 14

Where the Rubber Hits the Road: Trial Performance

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Organizing a trial strategy

Organizing a trial strategy

![]() Selecting the jury

Selecting the jury

![]() Presenting the case

Presenting the case

![]() Collecting on judgments

Collecting on judgments

Properly preparing for and carrying out the various tasks involved in trial practice require enormous amounts of the paralegal’s time and energy. When your employer specializes in litigation, you’ll concentrate on making sure your supervising attorney is ready for trial, and you’ll be on hand to assist both during and after trial. In this chapter, we describe the trial process from developing a trial notebook and selecting a jury to presenting a case to a court and collecting a judgment.

Creating the Ultimate Source of Information: The Trial Notebook

Even before you know whether the client’s case is going to trial, your office should begin to develop a trial notebook (which contains all the information and documents pertinent to a client’s case). Make no mistake about it: The best law firms get the jump on early trial preparation, and the paralegal plays a fundamental role in that process. It’s all about preparation and organization. A good trial notebook provides the tool any attorney needs to be a winning professional.

The first thing you do when getting ready to put together a trial notebook is read the client’s file from cover to cover to get a firm grasp on all the facts of the client’s case. As you go through the file, record notes about anything that doesn’t make sense or requires future follow-up. Pay attention to what isn’t in the file, such as medical or other expert witness reports, lab reports, and so on. Keep a sharp eye out for anything that will help you locate witnesses, and make notes of their names, addresses, and other identifying information.

When you have a handle on the facts of your client’s case, you organize the information in a logical fashion so your supervising attorney isn’t fumbling through a mass of information to find case details while working on the case in the office or the courtroom.

Arranging the trial notebook is sort of like putting together a binder for the first day of high school when you had to make divisions for all your classes. Here’s how you build it:

-

Get a three-ring binder wide enough to hold the amount of documents you expect to accumulate and organize over the life of the case.

Usually, the bigger the case, the bigger the binder.

-

Get dividers with large tabs and label them for the various sections of the trial notebook.

These sections roughly follow the order of events in the case as it plays out in court and usually include the following:

- Civil Pleadings/Criminal Charging Documents

- Pre-Trial Motions

- Jury Selection/Voir dire Examination (see “Selecting the Jury: The Paralegal and Voir dire,” later in this chapter)

- Opening Statement

- Witnesses (Direct Examination, Cross Examination, Rebuttal)

- List of Exhibits

- Jury Instructions

- Closing Argument

- Evidence

- Legal Authority

- Trial Notes

- Post-Trial Motions

- Miscellaneous

-

Include a trial preparation checklist in the front of the notebook.

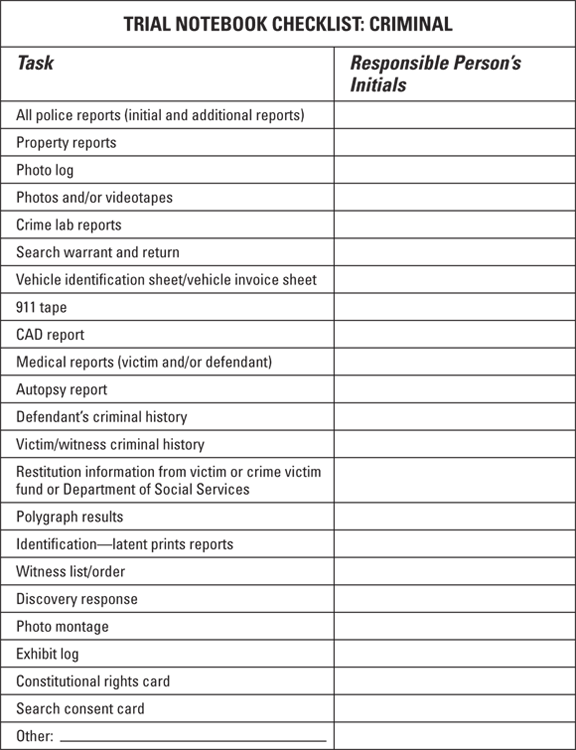

Figure 14-1 shows a sample trial preparation checklist for a criminal case that you can use to guide the way that you gather evidence and store it in your files. The person responsible for collecting each document initials the sheet when it makes its way into the trial notebook.

- Insert case documents into the appropriate sections of the notebook.

© John Wiley & Sons

FIGURE 14-1: A trial preparation checklist, like this one for a criminal trial, should go in the front of your trial notebook.

- Who: Names, addresses, and phone numbers

- When: Dates and times

- What: Discoverable material and physical evidence

- Where: Locations (for maps, photos, and the like)

In anticipation of trial motions and other court procedures, prepare blank documents before the trial starts. If the attorney needs to make a motion or suggest jury instructions in court, the attorney can do so very quickly both verbally and in written form. Having these documents ready at the attorney’s beck and call makes you appear very professional.

Selecting the Jury: The Paralegal and Voir Dire

The first step of the actual trial process for a jury trial is jury selection. Jury selection whittles down a large pool of potential jurors to 6 or 12 final jurors and alternates through a question-and-answer process called voir dire. Jury selection plays a crucial role in getting a fair and impartial jury for the trial. Attorneys question members of the jury pool to eliminate individuals who may be prejudiced in deciding the case. These questions also serve a second purpose: They’re the attorney’s first chance, even before opening arguments, to display the central themes of the case to prospective jurors. As a paralegal, you should assist your supervising attorney in preparing voir dire questions in advance to use with the jury pool, questions that may very well be key to the outcome of the case.

- Eliciting information about the biases of potential jurors

- Educating the jury about factual and legal concepts of the case

- Establishing a rapport with the jury

In important cases, your firm may call in a jury selection specialist to investigate the entire pool of potential jurors, which could consist of hundreds of people. The jury consultant advises attorneys on which jurors are likely to be sympathetic to one party or the other.

During voir dire, attorneys ask the members of the jury pool questions that address their qualifications to sit as jurors. Given a large jury pool, attorneys usually direct questions to the whole group. Based on the responses they get, the attorneys may then question individuals. Although lawyers never want to intentionally embarrass a potential juror, sometimes they have to delve into someone’s personal life. Personal inquiries help your firm weed out those jurors who might view your client’s case unfavorably.

Following is a sample list of voir dire questions directed to the group of potential jurors that you can adapt to fit many criminal or civil cases. Naturally, you alter the questions depending on the subject matter of any particular case.

- Is there anyone here who hasn’t read the juror’s handbook?

- Has anyone sat on a jury before?

- Has anyone heard anything about this case?

- <Names of individuals> may be called as witnesses in this case. Does anyone know any of these potential witnesses? Does anyone know the plaintiff, the defendant, the attorneys, or the judge in this case?

- This event allegedly occurred in <name of area>. Does anyone live near or is anyone familiar with this area?

- Has anyone ever been involved in or witness to the types of events surrounding this case? Does anyone have relatives or close friends who have been involved in or witnesses to the types of events surrounding this case?

- Does anyone have a personal interest in the outcome of a case of this nature?

- For criminal trials: Is anyone employed in law enforcement or in the justice system?

- For criminal trials: Has anyone ever had a bad or unpleasant experience with a police officer?

- Does anyone have religious, personal, or philosophical views that would interfere with sitting as a juror in this particular case?

- Does anyone have strongly held opinions about the nature of this case that would prevent you from following the law in this case?

- Is there anyone who cannot agree to follow the law and instructions as given to you by the court, whether you personally agree with them or not?

- Is there anyone who doesn’t understand that a juror’s job is to weigh the testimony of each witness, which means determining truth in the event that the parties disagree on an account of the facts?

- This case may involve some complicated facts. Is there anyone who has a problem with the time it may take to sift through testimony and evidence to attempt to sort fact from fiction?

- Would you refrain from voicing your opinion if it were unpopular with other jurors?

- Would you listen fairly to the viewpoints of other jurors and give them a chance to persuade you?

- Is there anything about this trial, as it has been described to you, that makes anyone uncomfortable about sitting as a juror?

- Can anyone think of any reason why you could not be a fair and impartial juror?

After attorneys have questioned prospective jurors about the case, they may exercise challenges to excuse those jurors whose biases would make them least favorable to the client’s position. You can assist the attorney so that she can intelligently challenge jurors for bias or otherwise. State law governs how attorneys may challenge prospective jurors.

- Peremptory challenges require no reason to excuse jurors.

- Challenges for cause must be made for a specific reason.

- Challenges to the array involve the removal of the entire panel of jurors.

Rebelling without a cause: Peremptory challenges

Peremptory challenges, as the name implies, are those that don’t require the lawyer to give a reason for excusing a prospective juror. The juror could be giving the lawyer funny looks or could be overly friendly with the opposing lawyer. Your supervising attorney may exercise the peremptory strike because he has a gut feeling that a juror would be bad news for the client.

You don’t get to have as many peremptory challenges as you want — otherwise, there would probably never be enough jurors in the pool to satisfy each side in a lawsuit. Depending on whether you’re involved in a civil or criminal case, each side to the lawsuit gets a certain number of peremptory challenges. For example, some states allow the parties to exercise three peremptory strikes in a civil case, and attorneys in a criminal case may have as many as six or more peremptory challenges. If the case is heard in a court of limited jurisdiction, or if the final jury panel consists of 6 instead of 12 jurors (for a criminal misdemeanor case), the parties may be limited to only three strikes. If there are two or more defendants, each defendant may get an additional challenge, and the prosecution might get an extra one as well.

Making a good excuse: Challenges for cause

Each side to a lawsuit is entitled to an unlimited number of challenges for cause. A challenge for cause is one that lawyers use to kick off a prospective juror for bias, whether implied or actual. Implied bias shows up when, for example, a potential juror is a family member or close friend of one of the parties. Actual bias occurs when a potential juror states that she can’t be fair to one or both of the parties. One classic example might be a rape victim who is called to sit as a juror in a criminal rape case. Although the juror could conceivably be fair, it’s far more likely that she would have an extremely difficult time hearing the facts of the case and keeping them separate from her own experience.

Each party has an unlimited number of challenges for cause. As long as the attorney can articulate a clear reason why a particular juror can’t be fair, the court will excuse that juror for cause.

Dismissing the kit and caboodle: Challenges to the array

A challenge to the array occurs when one of the parties requests the court to disqualify the entire pool of prospective jurors. A challenge to the array is also known as a challenge to the venire. A party may exercise a challenge to the array only in highly unusual circumstances. You might see this type of challenge at play when irregularities or illegalities occur — for example, if the clerk or jury administrator uses some means other than random selection or if he purposely calls in a panel of completely biased prospective jurors. Challenges to the array don’t happen very often; if you ever see this occur in one of your attorney’s cases, consider buying a lottery ticket!

Monitoring the pool

As the lawyers exercise their challenges with jurors and particular jurors are stricken from the panel, new jurors from the pool, or venire, may be brought forward to take their place and the makeup of the jury box changes. You can help your supervising attorney during this process by noting potential jurors’ reactions to questions and observing how they relate to attorneys for both parties. And, while the attorney focuses her attention on questioning one prospective juror, you can watch the reactions of the others.

You may keep track of the panel for the lawyer by drawing a schematic juror seating chart. When a successful challenge has removed a particular juror from the box, you write the name of the next juror in that same location in the box. This allows your supervising attorney to always know which jurors are sitting on the panel at any one time.

© John Wiley & Sons

FIGURE 14-2: A jury panel seating chart can help your supervising attorney keep track of the jurors.

Your supervising attorney may also rely on software to assist with voir dire. Existing programs help attorneys keep track of juror and offer predictions regarding a prospective juror’s potential biases.

Keeping Track of Witnesses

Often, the paralegal is responsible for ensuring that the party and witnesses are ready for trial and that they get to the proper courtroom on time. You should let witnesses know the time and place of the trial, any traffic conditions they might expect, and parking areas and fees if they drive. The party calling the witness needs to make sure that the witnesses are paid for their time as well as mileage.

You should provide your office’s client with the same information you provide the witnesses, and review with the client the plan for his activities during the trial. Usually, your supervising attorney handling the litigation will want the client to be beside the attorney in court for the entire trial. You should also discuss with the clients proper dress, demeanor, and nonverbal communication required to make the right impression on the judge and jury.

The supervising attorney will probably want to meet with as many of the witnesses as possible and, without actually coaching them, practice with them the line of questioning. Paralegals frequently participate in the witness preparation process; Chapter 12 has some helpful hints you can use in preparing the client and any witnesses for what they might expect in court.

You should help your supervising attorney determine the order that she’ll call the witnesses in to testify. She may choose an order that helps tell the story chronologically, or, to make sure she starts and ends her case on a positive note, she may slip the testimonies of weaker witnesses in between the testimonies of stronger witnesses. You can help determine which witnesses are more persuasive than others.

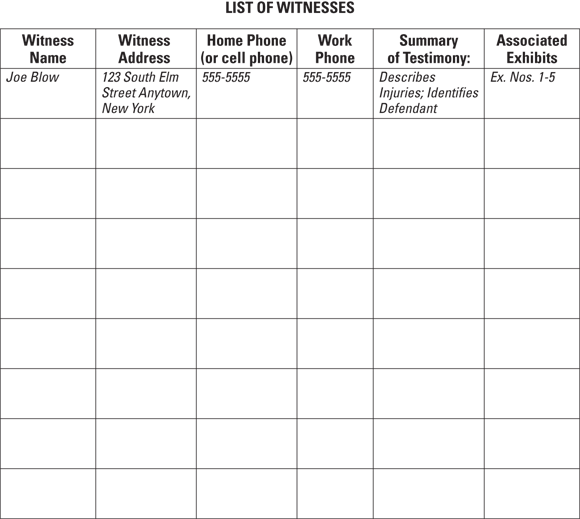

You may want to prepare a master witness list for use in trial preparation, but the master witness list comes in especially handy during the heat of the trial battle. Having witness contact information at your fingertips is critical, because your attorney may have to call a witness unexpectedly. Updating witness information is easy when you can rely on electronic trial notebook software applications.

© John Wiley & Sons

FIGURE 14-3: A master witness list can come in handy. You never know when you’ll need a witness’s contact info.

Weighing Testimony: The Paralegal’s Take on the Jury’s Reaction

Because the attorney focuses on the witness during examination, he cannot effectively evaluate the jury’s reaction to the witness’s testimony. This places you, as the paralegal, in a unique situation. Although your supervising attorney questions witnesses, you provide vital assistance by simply paying attention to what’s going on with the jury.

During trial, you take notes on witness testimony and evaluate the jury’s reaction. Most courtrooms don’t have the capability to instantaneously produce transcripts of the trial testimony, so your notes are invaluable to the attorney. They give him a check on what was actually said in the trial. Your notes of the proceedings remind the attorney of what areas need to be covered or followed up through the remaining witnesses. You further demonstrate your true value to the attorney by providing him with helpful hints on what points the jury felt particularly positive or negative toward. Your suggestions to the attorney often show him where he may have missed something important. You contribute a second set of eyes, a second set of ears, and even more brainpower to evaluate the proceedings.

Preparing Questions for the Attorney

Immediately before trial, the legal team begins writing speeches. The attorney prepares opening and closing arguments to emphasize to the judge and jury the overall point of the case. These oral arguments should be emotional and persuasive, and the attorney is likely to recruit you for practice and suggestions. He may also request your help in formulating questions for direct-examining witnesses.

-

Review the trial notebook for all documents related to a particular witness.

These documents include, but aren’t limited to, witness statements, notes from witness interviews, and deposition transcripts.

- Summarize all knowledge of the witness in an outline.

- Keep track of the witness’s testimony in rough chronological order.

- Formulate a question that will elicit each important element of the witness’s story for the court.

In addition to developing questions for the attorney to ask witnesses, you should also anticipate the other side’s testimony long before they testify to it at trial. This preparation allows you to help your attorney develop a line of cross-examination questions. Anticipating the opposition’s testimony is somewhat akin to playing chess. You need to figure out your moves ahead of time. If the other party says x, your attorney needs to be able to ask follow-up questions a, b, and c. If the other party answers with y, you need to come back with questions d, e, and f. This demonstrates to your attorney, and especially to the other party, that your trial team is thoroughly in control of the proceedings. Likewise, every time the opposing counsel examines a witness, you should take notes to prepare questions on the spot for your attorney to use in cross-examination and redirect.

Settling Up: Preparing the Cost Bill

You’re still not done when your client wins a judgment against the other party. A judgment is the final determination of the rights and obligations of the parties toward each other. If neither party appeals the judgment within a certain period of time, generally 30 days, the judgment becomes final. After the final judgment comes back in your favor, you need to notify the other side regarding its legal obligation to cough up and pay the piper. They usually don’t take it upon themselves to pay up, and they have no incentive to perform unless you tell them in the legal format of a cost bill. The cost bill is a summary of all the items the other side owes you now that the lawsuit is terminated.

- Special damages (medical bills, auto repair bills, and so on)

- General damages (like pain and suffering or embarrassment)

- Punitive damages (if allowed and ordered)

- Attorney and paralegal fees (if allowed by law)

- Filing fees (paid to the court)

- Court costs (set by statute or court rule)

- Process server fees (for service of summons and complaint)

- Expert witness fees (big bucks!)

- Court reporter fees (for depositions and so on)

- Jury demand fee (set by statute or court rule)

In some cases, it’s not entirely uncommon for the costs and fees associated with the litigation to far exceed the amount of damages recoverable.

Blood from a Turnip: Collecting a Difficult Judgment

Winning a judgment from another party in court and collecting on that judgment are entirely separate tasks. Unless the losing party is an insurance company or other large entity, your attorney probably won’t receive an immediate payment for a client’s judgment, which means you have to do some collection work.

For nearly every case, you have to find and quantify the assets of the losing party. To promote this process, you may draft interrogatories in aid of judgment (which are questions directed to the judgment debtor about her assets). In fact, the process of quantifying the opponent’s assets is so important that you may complete that task before the client files the suit rather than after. There’s no point in winning a judgment that you can’t collect.

Assets exist in many forms. All the following assets might be useful sources of revenue for a party collecting a judgment:

- Bank accounts

- Real estate

- Business and personal property

- Debts owed to the debtor by a third party

- Business ownership

- Financial instrument ownership, like stocks and bonds futures

- Good-will ownership in a business and its trademarks

- Intellectual property rights ownership, like copyrights, patents, and trade secrets

- Future income

- Cash holdings (Dishonest people have escaped from paying debts by eliminating their assets, hoping that those investigating them would forget to inquire about the retained cash.)

The point: If your legal team has gone so far as to prevail over the other side in court, you’ve demonstrated your tenacity and should be able to find creative ways to beat them in the asset recovery game. As a paralegal, you may be instrumental in the recovery efforts.

Trial notebooks may be paper based, electronic, or a combination of both. We outline the process for compiling a paper notebook here, but many law offices use trial notebook software programs and apps so that they can access information on a laptop or tablet. Electronic notebooks may integrate online legal research programs and may allow for evidence to appear on courtroom monitors. Even if you rely entirely on electronic data organization, print out a copy of the notebook for trial or mediation just in case you encounter Wi-Fi or Internet connection issues.

Trial notebooks may be paper based, electronic, or a combination of both. We outline the process for compiling a paper notebook here, but many law offices use trial notebook software programs and apps so that they can access information on a laptop or tablet. Electronic notebooks may integrate online legal research programs and may allow for evidence to appear on courtroom monitors. Even if you rely entirely on electronic data organization, print out a copy of the notebook for trial or mediation just in case you encounter Wi-Fi or Internet connection issues. Trial notebook preparation also includes organizing evidence. As a paralegal, you need to make sure that each and every item is ready for production at trial, accompanied with the necessary supporting documentation. Usually, you complete the evidence organization along with the trial notebook. You can store your side’s evidence electronically or in folders and boxes and gather it in one place for safekeeping. Each item of evidence consists of the original, any necessary copies, and notes on its history, including how and when it was found, how it was handled from its finding to the day of trial, and the names of the individuals involved in each step. You should then index the evidence collection so that at trial the attorney can instantly access any required piece of evidence. (For more about collecting and organizing evidence, see

Trial notebook preparation also includes organizing evidence. As a paralegal, you need to make sure that each and every item is ready for production at trial, accompanied with the necessary supporting documentation. Usually, you complete the evidence organization along with the trial notebook. You can store your side’s evidence electronically or in folders and boxes and gather it in one place for safekeeping. Each item of evidence consists of the original, any necessary copies, and notes on its history, including how and when it was found, how it was handled from its finding to the day of trial, and the names of the individuals involved in each step. You should then index the evidence collection so that at trial the attorney can instantly access any required piece of evidence. (For more about collecting and organizing evidence, see  Three primary goals of voir dire include the following:

Three primary goals of voir dire include the following:  Jurors who hold preconceived ideas about the nature of a case may not necessarily be disqualified for bias. If they demonstrate that they can set aside their prejudices to render a fair verdict, the court may not see cause to excuse these jurors.

Jurors who hold preconceived ideas about the nature of a case may not necessarily be disqualified for bias. If they demonstrate that they can set aside their prejudices to render a fair verdict, the court may not see cause to excuse these jurors.