CHAPTER 2

Globalization

Embracing the Global Generation

I find that because of modern technological evolution and our global economy, and as a result of the great increase in population, our world has greatly changed: it has become much smaller. However, our perceptions have not evolved at the same pace; we continue to cling to old national demarcations and the old feelings of “us” and “them.”

—The Dalai Lama

The scene of a typical Harvard Business School classroom in the 1950s would seem rather peculiar today. For one thing, there were no women. The MBA class would be composed mostly of white American men, dressed in business suits and taught by a male professor. Fast-forward to 2010. Displayed on the walls of first-year classrooms are the flags of countries from around the world, representing each member of the class. You’ll hear a plethora of accents. More importantly, if you listen closely, you’ll learn that the educational and professional experiences that these students bring to the classroom also span almost every country and region. Globalization has become as commonplace in MBA programs as in business itself.

The next generation, more than others, is taking advantage of the learning opportunities globalization provides. Instead of simply using their formative years to develop their professional skills, young people in business have used globalization to gain practical experience earlier in their careers, learn more about different cultures, and ultimately, learn more about themselves. Like it or not, globalization is now an inescapable part of the emerging millennial zeitgeist, whether this means work experience in a multinational company, participation in addressing global problems such as climate change, the pursuit of new ventures abroad, or connection to an expanded international network.

According to the IBM Global Leaders Survey, when respondents were asked to name the top factors that would impact organizations in the future, globalization garnered the most votes, with 55 percent of students ranking it number one. In contrast, CEOs voted globalization the sixth most significant factor. In the same survey, students were 46 percent more likely than CEOs to identify “global thinking” as a crucial leadership skill in the coming years.1

In short, the next generation views globalization in a fundamentally different way—and this has ramifications for companies, governments, and international institutions around the world.

Can Globalization Build Better Leaders?

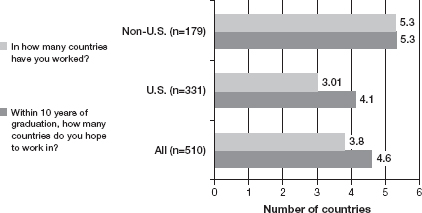

Working in an international setting has become the new normal for young leaders. In our MBA Student Survey, respondents had worked in an average of 3.8 countries, including their country of origin. International students tend to have worked in more countries—MBAs born outside the United States had worked in an average of 5.3 countries, versus 3 countries for those born in the United States (figure 2-1).

FIGURE 2-1

Today’s MBAs seek global experiences

After pursuing international opportunities early in their careers, young MBAs expect to have worked in even more countries by the time they hit their midthirties. Our respondents expect to work, on average, in 4.6 countries within ten years of graduating from business school. Forty-eight percent intend to work in 1–3 countries, 32 percent intend to work in 4–6 countries, while 10 percent would like to work in 7–9. Once again, country of origin also matters in choosing how global one’s future career will be: those born outside the United States intend to work in an average of 5.3 countries in the next ten years, compared to 4.1 countries among those born in the States. As a result, this generation of managers will have more global aspirations and experiences than any in history. This comes with its own challenges and opportunities.

The first challenge is the complexity that a boom in global business creates. Globalization, particularly trade liberalization, doesn’t always move forward in a straight line. Despite the explosion in trade, with more than two hundred free trade agreements signed in the last two decades alone, the global economic crisis has brought about renewed fears of protectionism.2 Yet despite the current gloom, it’s hard to ignore the staggering explosion in the number of multinational companies around the world. There were approximately 79,000 multinational companies around the world in 2006, up from 7,258 in 1970.3 And their leaders are seeing a very different global economic environment from the one that marked the past four decades. In the 2010 McKinsey Global Survey, 63 percent of more than 1,400 executives expected increasing volatility to be a permanent fixture of the global economy.4 And in the IBM Leaders Survey, students pursuing MBAs were 28 percent more likely than CEOs to believe that the new economic environment is increasingly complex.5 Inevitably, young people will play an important role in helping these new multinationals navigate uncertain global markets, especially in demographically young regions like India and Southeast Asia.

One respondent in our survey summed up the next generation’s sentiments about globalization nicely: “Leaders will be forced to unify groups with greater and greater diversity. They will ask for sacrifice from men and women who have rarely been asked to give up much. They will be required to explain issues that are growing in complexity and scope with the same simplicity as leaders have been required to do in the past.”

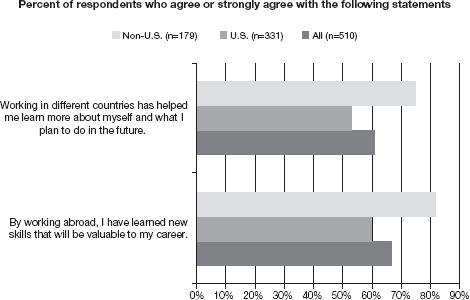

The second challenge is increasing and enriching the global exposure of young leaders early in their careers. This is crucial in helping them to get comfortable with uncertainty, and to grow the knowledge, skills, and networks to thrive in a world filled with it. The general importance of working abroad to develop one’s skills seems to be more important among international MBAs. Eighty-two percent of non-U.S.-born MBAs agree or strongly agree that “by working abroad, I have learned new skills that will be valuable to my career,” compared to 60 percent among American-born MBAs.

Young people will also have to address the crises of identity that globalization inevitably creates. Globalization has influenced young leaders’ sense of identity in two ways: by helping shape common values that transcend national and cultural divisions, and by taking them out of their comfort zone and forcing them to learn more about themselves.

Growing up in a time of ubiquitous globalization and connectivity, today’s twenty-something manager has developed values that transcend country or culture. As one of our respondents said, “Leadership will increasingly be attributed to improving the lives of others around the world. By the end of the twenty-first century, one’s actions will be judged more on [their] impact, on what we call ‘externalities’ today. We will get better at determining the value of these externalities, and this will have to be a priority for any leader.” What’s fascinating is that as young people around the world develop a shared sense of global citizenship, they’ve also become more astute students of local and unfamiliar environments. Consider the cases of contributors such as Andy Goodman, who grew up in the United Kingdom and helped the government of Qatar establish a new educational program, or U.S.-born Christopher Maloney, who worked in Rwanda. Their global perspective is built around a series of local experiences.

Global experiences have also become a crucial way for the next generation to develop a sense of personal purpose. In the MBA Student Survey, 61 percent of respondents agree or strongly agree that “working in different countries has helped me learn more about myself and what I plan to do in the future” (see figure 2-2). This holds more true for MBAs born outside the United States, as they are 42 percent more likely to agree with this statement than those born in the U.S. Part of this is driven by global educational opportunities. In 2005, there were 2.7 million foreign students enrolled at tertiary educational institutions around the world. And though traditional sources of foreign students such as Hong Kong, Japan, Korea, and Malaysia are expected to plateau and eventually decline, “sunshine” markets such as India, China, and Chile are expected to pick up the slack and drive the growth of mobile international students.6

FIGURE 2-2

MBAs find immense benefits in working abroad

The third challenge is adapting to the shift in global political and economic affairs—the “rise of the rest.” While it’s been fashionable to say that globalization is no longer driven solely by the West, nobody really knows for certain how a multipolar world will take shape. This shift has enormous consequences. A unipolar world is shifting to a complex multipolar global economy. Chinese and Indian companies have been aggressively expanding overseas. Indian companies announced more than a thousand M&A deals, valued at $72 billion, between 2000 and 2008.7 Chinese companies, meanwhile, are buying foreign companies from Africa to Singapore to gain access to precious oil, gas, and mineral resources to fuel the country’s expansion. The share of developing Asia in global GDP has more than tripled to 23 percent in 2010, compared to 7 percent in 1980.8

Young MBAs see this trend. When asked which countries are the most important for businesspeople to understand in the next ten years, respondents of the MBA Student Survey voted China the overwhelming favorite, with 63 percent decisively ranking the world’s most populous country first. India came in a distant second with 11 percent, and other developing countries were frequently highlighted.

The rise of the rest undeniably requires integrative work across functions, cultures, and classes. Young leaders will have to adapt to places where extreme poverty is spurring new ways of creating value through the role of private enterprise in delivering public infrastructure such as water, energy, and health care, or minimizing externalities such as pollution and social inequality. When asked openly on how leadership will change in the twenty-first century, learning to manage in an interdisciplinary way emerged as a recurring theme on the MBA Student Survey. As one student summed up nicely, “I think that leaders will be forced to work globally in a way they haven’t before—requiring leaders to understand and adapt to different cultures, manage teams and relationships that span the globe, piece together divisions and companies that operate under completely different environments.”

Bridging Two Worlds

An India Story

SANYOGITA AGGARWAL leads business development at Dev Bhumi Cold Chain Ltd. in Delhi, India. She received her MBA at Harvard Business School in 2010. San talks about the decision to return to India after studying abroad and the surprising, often counterintuitive, lessons she’s learned in bringing global best practices to a traditional family business.

Upon graduation from Cornell, I had to choose between two paths. One was to work for Morgan Stanley in New York; the other was to work in our family agribusiness company in India. Most of my best friends were going to be in New York, and Morgan Stanley offered a traditional path to prestigious institutions for higher education. On the other hand, I also longed to be home. It was a personally hard decision to make. But in the end, I chose India.

India was not only my home; it was also the new land of opportunity. It was poised for explosive growth in the coming decade, the place where we would witness societal change unfold. With the second-largest population in the world and retail giants like Walmart and Carrefour zeroing in on India as the “next big thing,” there was no doubt in my mind that the future here would be full of promise and optimism. This was a far cry from the India of the 1970s, which suffered from political instability, hyperinflation, high unemployment, and decrepit industries. The bright optimism in India in the first decade of the twenty-first century mirrored that of the United States in the 1950s. And it was contagious.

So, I decided to work in Delhi with my dad in his agribusiness company, Dev Bhumi Cold Chain Ltd. The company is a complete one-solution provider for farm-fresh produce, starting at the farm and ending on the supermarket shelves. I was beginning to look forward to the experience.

Confronting Reality at Home

When I started working with my father, I was expecting it to be familiar territory. I was hungry and passionate to do big things in an environment I thought I understood. Brimming with ideas, bursting with ambition, and full of confidence, I had no inkling of the troubles ahead. The next few months brought reality home for me.

The company was entrenched in the “family business” way of working. In other words, employees were not evaluated on any performance metrics, work was carried out in an ad hoc manner, and there was a lack of organization and systems. Many thought that the business of fresh produce was fit only for men. Women would never be able to adapt. Consequently, I was the only woman in the company. Not only did some of the old senior management object to my coming to the office, but some of the new female staff that I hired faced a lot of heat. One of the new female MBAs hired for marketing faced significant opposition and noncooperation from various fronts, and eventually she quit. Furthermore, many in the company disproportionately valued experience over education. My American education was seen as an obstacle rather than an accomplishment. My “new” ways were despised, looked upon with suspicion, and labeled as impractical.

One of my very first projects was to set up a mineral water plant at the company’s Himalayan facility. This project had been sidelined due to skepticism and contention within the organization about its future benefits. So when I decided to conduct a feasibility study to conclusively decide the potential, there was widespread dissent, touting this exercise as a waste of energy and company resources. Every activity I undertook for this project met with hostility and noncooperation. Halfway through the study, my budget was completely withdrawn for a few months because I was told that the company resources needed to be dedicated to core activities.

Four months into the job, I was seriously considering quitting. What made me stay?

Establishing Roots, Making a Commitment

Indian agriculture has long suffered from outdated pre- and postharvest technologies as well as antiquated systems. The average yield of apples for the Indian farmer, for example, is approximately 5 metric tons per hectare, compared to a whopping 60 metric tons per hectare for his European or American counterpart. In addition, an estimated 40 percent of fresh produce is lost in value and kind due to the lack of cold chain infrastructure in the country. Despite these dismally low yields and the staggering wastage, India continues to command a 10 percent share of the global production of fruits and 13.7 percent of vegetables. The opportunity is simply mind-boggling. With the right systems in place, India could very well become the “fruit bowl” of the world. A complete cold chain infrastructure that starts at the farm gate with procurement facilities for the farmers; takes the freshly harvested produce through the entire chain of cold storage facilities, uses refrigerated trucking, packaging, and palletizing; and delivers fresh produce into the hands of the end consumer would elevate India to the world platform in agriculture. However, one of the biggest obstacles to achieving this objective is educating the Indian farmer.

To do so, our company started the Yield Improvement Program. The objective of the program was to work closely with farmers to introduce higher-yielding varieties of fruit and educate them on the latest pre- and postharvest technologies, in conjunction with following food safety protocols and promoting sustainable agriculture. During one of our initial visits to the Himalayas, while conversing with the locals, one farmer said, “We absolutely love this program and are fully on board with you. If your intentions materialize, generations to come will never forget you.” This left a lasting impression on me and at that point, I realized the immense impact this program could have on the farmers in the area and, eventually, the entire country. I believed that the goals I was pursuing reconciled the profit motive with the right underlying social objectives. I fell in love with what we were doing, and this outweighed the daily predicaments I faced in the workplace. So, I decided to stay and confront my problems head on.

Changing the Status Quo

I learned several important life-changing lessons, lessons that hopefully will be relevant to anyone hoping to do business in India, working in a family business, or entering an unfamiliar market.

First, I witnessed firsthand how change is always resisted. The best way to make change is to first understand the reasons behind the status quo, then become a part of the system, gain people’s trust, and make the change slowly but steadily. It’s easy to approach problematic situations thinking that most things should be changed from the ground up, as fast as one can. But I realized that confrontational attempts at change are the most damaging. Most of the time, there aren’t any real reasons for this stance except for the manager’s hubris to leave his mark quickly. When I got past my youthful naiveté, it dawned on me that the most meaningful changes must be initiated at a slower pace.

In my particular case, to address the sensibilities of the staff, I started wearing only Indian attire to the office. Once everyone got comfortable with me, I slowly changed to Indo-Western clothing and then to my normal Western outfits. For the female staff, I decided to hire candidates already known and trusted within the company. For example, we hired the daughter of an existing staff member, and since she already knew most of the people in the company, she found it much easier to adapt and fit in. Most of the senior management, who had previously resisted all female hires, considered her like their own daughter. Hence, they were more protective of her and cooperative in helping her understand the work and the systems.

I learned that local conditions can lead to very different and unique solutions. In the United States, for example, I would never have considered this approach for fear that my action be termed as favoritism. But it worked wonders in my Indian situation. This woman quickly grew very comfortable working in the difficult environment, and the staff soon acclimated itself to her. This ultimately opened the door to new female hires who now had not only a more receptive organization but also a ready mentor.

Second, I learned not to fall prey to a one-size-fits-all philosophy of leadership. Unique problems always call for unique solutions. For example, in my initial months in the company, I came to realize that our employees placed a strong emphasis on relationships with clients and suppliers, and less, or none at all, on quantitative analyses. Business decisions were often made on the basis of old associations and relationships, and completely without any NPV or IRR calculations. Thus, the most important leadership skill I’ve learned—and would encourage my peers to learn—is to be sensitive to the intricacies of the situation at hand.

I soon realized that an amalgamation of both quantitative and relationship-driven approaches would lead to a “best of both worlds” result. Coming from a strong educational background in quantitative business management, I found focusing on relationships baseless and immature. But I soon realized the immaturity of my own thinking. There was no black-and-white answer to this. No one way of working was better than the other; the two were simply different. The Indian way of working relied heavily on a “trust” culture, and a lot of business was conducted based on good faith. One glaring example of this was what I saw in the fields while talking to farmers during the procurement season. Huge multinational mammoths were out to procure from the same fields and the same farmers at higher than market rates. Despite the monetary advantages, the farmers somehow preferred to sell to us. Logically, this made no sense. When asked, one of them replied, “It’s because we have faith in you. We have worked with Dev Bhumi for many years and we know you would never cheat us. Money is not everything and our relationship is based on a lot more than just rupees.”

Last, I learned interesting lessons on how to adapt to a family business environment, a situation that I foresee several of my peers face as they return to Asia, where family-owned and -controlled companies are the norm. Working in a family business is not only about the bottom line, but also about legacy and emotional attachments. Many projects in family businesses are driven more by the founder’s passion than by purely economic reasons. The founders often invest their personal wealth and life into building these businesses, and many of their memories are associated with the grueling efforts they put in.

Family businesses have been and will continue to remain important drivers in India’s economic future. They account for roughly 65 percent of the economy’s GNP and for 75 percent of the employment in the country.9 The new generation inherits the responsibility of taking the business much further than the previous one and needs to earn the credibility and respect of its peers and employees. I learned that working in a family business also requires a very entrepreneurial attitude, especially in interacting within the company.

In my case, as the fourth generation in the family business, I was expected to hit the ground running from day one. My challenge was more than just problem solving; it was also getting buy-in from the staff, proving to them that I was capable of the responsibilities handed to me. The first approach I applied was to start small with projects that could be completed in a short period of time. Small projects allowed me to have a lot of interaction with different groups of people and better get to know them and their problems at work. This increased our comfort level of working together and we soon transformed from a group to a team.

As the next generation transitions in, it becomes important to thoroughly understand the undercurrents of the business. In family-run companies, often the staff members are equally committed and passionate about the business and share the founder’s values and principles. The next generation needs to demonstrate the very same ideals that represent the foundations of the company. One of our company ideals is to provide for better living to all staff members through higher education opportunities and extracurricular experiences. I initiated English classes at the office for staff who were not fluent. We also started the policy of paying for complete school education for children who showed high academic performance in school. All this helped the staff to realize that I was just as committed to them as they were to our company.

In retrospect, the decision to continue on in India turned out to be one of the most fulfilling commitments of my life. It was here that I learned what doing business in the real world truly means, what it means to be a part of the system and yet be an agent of change, and what it means to become “comfortable being uncomfortable.”

QatarDebate

Education, Civic Engagement, and Leadership in the Arabian Gulf

ANDREW GOODMAN graduated from the Harvard Business School in 2010 as a Baker Scholar. Before attending HBS, Andrew cofounded QatarDebate, a civic engagement initiative that aims to develop and support the standard of open discussion and debate among students and young people in Qatar and the broader Arab world. Andrew’s story helps young leaders appreciate the importance of cultural intelligence, the right partnerships, and a pipeline of local leaders in building ventures in unfamiliar markets.

If you had asked me when I started college in England if I expected to find myself two years later in the midday heat of the Qatari desert, being filmed balancing precariously atop a camel with a Scottish man in a kilt, the answer would probably have been no. The state of Qatar is a tiny desert country at the tip of the Arabian Gulf. A conservative Muslim country, ruled by an emir, it is home to 1.6 million people and the world’s third-largest reserves of natural gas, from which the country derives its prodigious wealth. Before the summer of 2007 it was certainly not a place I had ever imagined commuting to every month during my final year at Oxford and the first year of my MBA at Harvard.

It was a passion for education that drew me to the Middle East. Qatar is richer per capita than Luxembourg or Switzerland, but its scores on the PISA tests, which assess students’ educational literacy in math, reading, and science, are comparable to those of the former Soviet republics of Azerbaijan and Kyrgyzstan. In historically failing many students, Qatar’s education system is by no means unique. However, unlike most other countries with very poor educational outcomes, Qatar has a rare combination of advantages: the leadership, willingness, and funding to implement genuine education reforms.

From the early 2000s, the emir, Qatari government, and Qatar Foundation embarked on an ambitious education reform program. From these reforms came substantial changes in both secondary and tertiary education. At the secondary level, reformed, charter-style “independent” schools were created that used a new syllabus and were accountable for their results to a Supreme Education Council. At the tertiary level, Qatar Foundation invested billions of dollars to develop an “Education City” that housed the branch campuses of six leading U.S. universities and numerous other education initiatives.

An Unusual Job Interview

My time in Qatar began in the summer of 2007 with an unusual job interview. Alex Just, a colleague from Oxford, and I were invited by Ali Willis, an executive director at Qatar Foundation, to spend ten days in Qatar, working with students to improve their debating, civic engagement, and critical thinking skills. At the end of the ten days, Alex and I were asked to attend a meeting with Her Highness Sheikha Mozah Bint Nasser Al-Misned, the Queen Consort of Qatar and, in her role as chairperson of Qatar Foundation, one of the leading education reformers in the Middle East. We were told simply to expect the unexpected.

At the meeting, we suggested that Qatar Foundation create and fund a national organization to work with students and teachers within the Qatari education system to improve critical thinking and civic engagement. Our background had been in competitive debate, where teams of students would compete in national and international competitions to hone arguments and marshal evidence to support an assigned position on a variety of moral, political, and social issues. We believed that this type of training—at that time mostly alien to the region—built skills, civic engagement, and a connection to a global community of high-achieving students. Such a national organization could therefore be based initially around a culture of debate and discussion, gradually expanding to incorporate other elements and pedagogies.

As we flew back to the United Kingdom following the meeting, we reflected that Qatar was a fascinating country, and despite our preconceived notions about conservatism in the Arabian Gulf, a large number of the students we had met seemed to embrace the concept of debating important political, moral, and social issues. We knew, though, that governments and national foundations were not generally in the habit of entrusting millions of dollars of funding to unproven undergraduates.

It was therefore a surprise when Ali called us in Oxford a few days later to say that Sheikha Mozah had recommended that Qatar Foundation fund our project, and that we should make arrangements to start work immediately as program directors . . . in Qatar. Alex and I would be working under a mandate to fill just a small piece of Qatar’s broader educational puzzle—student engagement and critical thinking—creating a national organization that would foster an emerging culture of debate and discussion among students in Qatar, with the hope of developing the country’s “leaders of tomorrow.”

QatarDebate

Over the eighteen months after our initial meeting, Alex and I, under the direction of Ali and with the support of Qatar Foundation, created and managed a national civic engagement initiative for Qatar that would become known as “QatarDebate.” Life took on a surreal rhythm, writing undergraduate essays in the rain and gloom of the Oxford winter one day, and the next, pitching the importance of debate as an educational tool to education ministers from around the Arab world in the heat of the Qatari capital, Doha, living out of suitcases and working from Qatar Foundation’s headquarters, airport lounges, and our university dorm rooms.

In its first eighteen months of operation as a not-for-profit start-up, QatarDebate worked with more than three thousand students and teachers in thirty schools and universities in Qatar. We delivered a curriculum to students that encouraged them to think critically about the world, contest complex concepts, and challenge political and social beliefs. Schools and universities formed debate teams that constructively and often heatedly discussed policies from censorship to negotiating with terrorists to Islamic dress on a weekly basis. At an international level, we created, selected, and coached the first Qatari national debate team, which went on to break records at the World Schools Debating Championship as a first-time entrant. We distributed curriculum materials on debate and civic engagement to partners in more than fifty countries, including every state in the Arab world. We even successfully bid to host the world championships in Qatar in 2010, exposing Qatari students to some of the brightest young minds from more than forty countries, including the United States, Israel, and Mongolia.

We were given access to former heads of state and education ministers from around the Middle East to explain the importance of debate and citizenship education, and provide a blueprint for similar national programs in their countries. In the media, we brought student debate to prominence on the often controversial satellite channel, Al Jazeera, and were featured in an award-winning documentary that premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival in New York. Sitting in a cinema on the Lower West Side and observing New Yorkers watch Qatari, Iraqi, and Syrian students engaging in an intellectually rich discussion of U.S. policy in the Middle East since 9/11 on screen is an experience that I will never forget.

Launching a Start-Up in the Arabian Gulf

The experiences of launching and operating QatarDebate highlighted several of the challenges that come as part of launching an organization as an outsider in an unfamiliar environment.

How to organize. The relatively simple process of creating an LLC, public limited company, 501(c)(3), or registered charity is typically taken for granted in the United States and Western Europe. In an emerging market like Qatar, the process of creating an organization presents often overlooked challenges and pitfalls. To create a new charity in Qatar requires paperwork, time, and approval from the government. We launched QatarDebate within an existing organization, Qatar Foundation, and as a result were able to start operations immediately and benefit from the foundation’s funding and goodwill. In contrast, even major multinationals entering Gulf markets as new entities find themselves waiting several months for the required documents and permits to be approved. However, to position your new entity within or in partnership with an existing organization is to be bound by additional policies, procedures, and protocols in the longer term. Young managers confronted with the realities of an unfamiliar market must find balance between speed to market and freedom of operation, or be fortunate enough to find a rare partner that offers both.

How to bridge cultural divides. Within our first few weeks in Qatar, it quickly became apparent that there was a gulf between the fundamental paradigms of U.S. and Qatari education. When our Western-educated trainers entered the classroom, one of the first questions they faced from Arab students was simply, “What is debate?” To many students, the concept of critically discussing important political, moral, and social issues was entirely new. Alex and I were often unsettled early on when confronted by culturally “different” events—in one instance a highly educated woman wearing the niqab (face veil) and yet strongly advocating that this choice was a woman’s right and an expression of freedom. We quickly learned that the Arabic word inshallah (God willing) had a multiplicity of meanings, and often wondered if specific divine intervention was required to accelerate meetings, permits, and procurement orders. Managers in emerging markets must draw a mental line between those cultural differences they will embrace and those things on which they will stand firm.

How to measure impact. Observing the academic progress of students who had been through QatarDebate’s programs demonstrated in our minds the ways in which the coaching improved their critical thinking, structure, and English fluency. To prove impact, though, we needed to develop a much more rigorous assessment process that tracked cohorts of students over time. Young managers in emerging markets should be aware that they will have to modify their existing assumptions about research and tracking. Market research in the Gulf is thought to be at least twice as expensive as in Western markets, and traditional survey methods face severe constraints. When entering a market in the Gulf, organizations need to have rigorous KPIs (key performance indicators) to avoid spending large amounts with limited ability to prove impact, but managers also need to be specific up front about what meaningful data they will actually be able to collect, sometimes departing from standard metrics and getting creative about what measures might provide a reliable proxy for some other outcome that they are not able to observe directly.

How to lead. When it comes to leadership in the Gulf, we found that small is often beautiful. By working with students in a relatively small country, we genuinely had the potential to change the way those young people will think about the world in the future, for better or for worse. Those students whom QatarDebate spent hundreds of hours coaching, now imbued with a new set of tools with which to evaluate the world, will very likely become the key decision makers within business, government, and society in Qatar. When observing those multinationals who had been successful in Qatar, we saw a similar phenomenon. Successful companies who had entered the market brought experienced expat staff, but over time, the most successful companies hired a small number of very talented locals into genuine leadership development schemes. These Qataris were given incredible amounts of training and exposure, and they were told to aspire to be the future CEOs and executives at those multinationals. Less successful firms complained about a dearth of local talent, but the market leaders set about generating their own local talent pipelines from the very beginning.

How to transition. For a national organization to become truly sustainable in a world in which individual leadership is only ever temporary, it needs to be run, at least in part, by nationals. Expatriates can bring significant expertise and dynamism, but they will never quite be able to match local managers in cultural insight, local knowledge, and a desire to make their lives in that country. Resistance to this reality is dangerous—the Gulf has historically seen many examples of the vicious cycle in which expats fear losing their positions in the longer term and therefore act to maximize short-term gains. Locals in turn perceive foreigners as concerned more about their short-term gains than long-term sustainability. Handing over control of QatarDebate’s day-to-day operations and watching a new, Qatari leadership team embark on a new and different path was extremely challenging—QatarDebate was after all something that we had created—but it was the right thing to do to create a truly national organization.

Leaving Qatar

My time in Qatar drew to a close in July 2009 as the full transition to a Qatari leadership team for QatarDebate concluded, and I decided that I would return to the United Kingdom after completing the MBA. I look back on those eighteen months as my first leadership role—a plethora of incredible enriching, rewarding personal experiences. Many of the challenges faced were similar in nature, although definitely not in scale, to the challenges faced by countless case protagonists that I have subsequently encountered during my two years at HBS. With hindsight and the imparted wisdom of various cases and scenarios, I would certainly make many decisions differently. However, Qatar “made real” for me some things that had been lost over the course of the seven hundred or so MBA cases.

As I sat with a Qatari friend on Doha’s Corniche on one of my last evenings in Qatar, watching the sun set over the Arabian Gulf, we found ourselves discussing the fascination modern business education in the United States has with “leadership.” Leadership in the Gulf and beyond, my Qatari friend concluded, required the serenity to accept the things you cannot change, the courage to change the things you can, and the wisdom to know the difference.

Emerging Social Enterprise

Learning the Business of Agriculture in Tanzania

KATIE LAIDLAW is a consultant in the New York City office of the Boston Consulting Group. Prior to joining BCG, Katie was a senior associate at the Parthenon Group and served as executive director of Inspire, Inc., a nonprofit organization that advises community-based nonprofits. She is passionate about international development and future growth in public-private partnerships.

Deo, the local government agriculture officer assigned to Mhonda, directed me to sit in a red plastic chair as farmers entered the weathered brick structure in the center of the village. Mhonda, Tanzania, was my first stop along a series of village visits to gather field data through farmer group interviews during a summer internship with TechnoServe, a U.S-based international nonprofit focused on poverty reduction through economic development. TechnoServe hired me to work independently on a three-month study to analyze the fruit and vegetable markets of Tanzania. After a seven-hour truck ride over freeways, dirt roads, mud trails, and mountainous terrain, I was excited to continue learning about the business of agriculture in Tanzania firsthand from farmers.

I smiled at each farmer who entered the meeting space. They stared back at me with facial expressions exhibiting everything from cautious optimism to anxious skepticism. They were not yet sure of what I wanted or offered. I noticed how each farmer arrived with his or her own smoothed sitting stone. Seeing them sitting perched upon stones in seemingly uncomfortable, crouched positions, I felt instantly self-conscious about my thronelike chair. I then nearly committed a serious, albeit unintentional faux pas by attempting to lower myself discreetly to the dirt floor to join them. Deo quickly corrected my move before I fully sat down by simply stating, “Visitors sit in the chair. You must sit, you are a visitor.”

Feeling a bit flustered, I quickly reviewed my questions for the group interview. The purpose of my project was twofold: to identify opportunities within or beyond the existing supply chain that could result in increased farmer income, and to submit a completed grant proposal in order to access funding for the implementation of any proposed plans.

For me, this opportunity to gain international field experience across private, nonprofit, and public sectors through TechnoServe was a dream. Social enterprise, the pursuit of innovative opportunities to create social value through market mechanisms, is one of my personal passions. I knew that this three-month experience would be a short-term entrée into a lifelong, multisector career at the intersection of business and social change.

Assembling the Puzzle Pieces

The data I gathered through farmer interviews informed the creation of a pro-forma profit and loss statement for growing and selling fruits and vegetables throughout the year. Starting with a baseline financial perspective, I brainstormed ways to change assumptions of cost and revenue drivers, with the goal of increasing farmer income. In addition to the more specific data inputs, farmer group interviews also answered questions about their savings rates (low), up-front seed and fertilizer input costs (high), and investments in more sophisticated processes like irrigation (low and rare). Due to the seasonality of planting and the lack of access to savings or banking, I could not directly ask farmers how much money they had made in profit in the past year. Instead, I cobbled this data together by analyzing what was planted and harvested throughout the year, typical high and low market prices, and what volumes were actually grown and sold.

Data collected in each village helped to narrow my focus on farmers producing primarily mparachichi (avocados) and nyanya (tomatoes). And thus, my “guacamole plan” was born. I honed in on the differences between these two fruits and suggested a comprehensive plan to support groups of farmers through pilot programs in two distinct farming regions in Tanzania. I supported TechnoServe’s Tanzania country director to complete a grant proposal to a large U.S. international development funding agency identifying the need and income increases possible through interventions with avocado and tomato farmers. As the grant proposal served as a summary of my field findings to date, I started to recognize other peripheral constraints to operating in the international nonprofit space that impacted my understanding of the sector.

Patience, Not Speed, Is Required for Results

Constraints on time, human capital, or funding (or all three) are common across the private, public, and nonprofit sectors. While success in the for-profit sector is often measured by stock performance, progress in the nonprofit sector, particularly international development, can be more challenging. Stock prices change in real time. Measurable gains in tomato production or avocado quality require a longer runway to implement change and measure impact, and adjustments in perceptions, culture, and expectations in emerging economies are even more ethereal.

I was surprised to discover that most global aid programs are built upon the expectation of three to four years of funding, often with no renewal. This funding approach is severely disconnected from any longer-term goal of institutionalizing improvement. Just as many development programs hit their stride in meeting goals, funding ends, leaving a well-designed idea half-tested and uncertainty around what truly “worked.”

The nonprofit sector plays a unique role in global capitalism. It is not predominantly concerned with campaigning and election as in the public sector, nor subject to the scrutiny of private sector shareholders. It is, instead, a useful go-between. The sector provides a way to work with and within global markets and local politics to encourage real, on-the-ground change. But the nonprofit sector, particularly in the field of international development, will need to increasingly free itself from the constraints of short-term financing to achieve lasting impact.

Applying Lessons from One Sector to the Other, and Vice Versa

At the end of my time in Tanzania, I felt confident in what I had learned from my experience as well as in what I had contributed to designing a program for agricultural economic development. This experience confirmed my own hypothesis that future leaders will be better equipped to tackle the problems of tomorrow by being successful in operating across geographies and sectors today. Leaders must also recognize that there are no longer silos but, rather, continuous opportunities to achieve greater social good through collaboration.

Throughout my time in Tanzania, I relied upon skills from my private sector training, my previous nonprofit sector involvement, and my willingness to learn and understand new approaches specific to the international development community. The opportunity to work in agriculture provided me with new information and perspectives that I have since applied in other industries. By establishing a consistent company relationship with a single organization or encouraging employee choice, for-profit businesses today can benefit from expanded employee perspectives gained by working in a nonprofit or public sector arena, in very unfamiliar environments.

The same benefits of global, cross-sector involvement can result when nonprofits seek for-profit or public sector resources as a complement to their internal capabilities. Though I lived and worked in Tanzania for a brief time, I felt that my final outputs contributed to longer-term knowledge and resources of TechnoServe. Nonprofit leaders today can fill gaps or further challenge their organizations by looking beyond their sector and benefiting from short-term engagements with public and private sector organizations.

Investing Time and Resources for the Changing Global Economy

Upon returning to the HBS campus, I served as a copresident of the Social Enterprise Club, the student-run umbrella organization offering programming and networking opportunities for HBS students interested in this intersection of market mechanisms and the social sector. The Social Enterprise Club continues to grow in membership and is currently one of the largest clubs on campus. This membership metric demonstrates the increased awareness by business school students of the personal value of doing good in one’s community and doing well in one’s professional life, concurrently throughout a career.

During the start of my fall semester, I learned that the proposal submitted for this avocado and tomato project had received a multimillion dollar grant. It was a deeply fulfilling and satisfying outcome. News of winning the grant reminded me of so many distinctive memories of my summer traversing along the highways and dirt roads of Tanzania’s Southern Highlands. My awkward and uncertain start in Mhonda village, seated in a red plastic chair, was a distant but wonderful reminder of future possibilities to tackle some of our society’s largest problems through the intersection of private, nonprofit, and public resources. And young people like me can find an enhanced sense of purpose through pursuing them.

Global Citizen Year

Learning from the World

ABIGAIL FALIK is the founder and CEO of Global Citizen Year and a recognized expert in the fields of education reform, international development, and social innovation. For her work as a leading social entrepreneur, she has received awards from the Draper Richards Foundation, the Mind Trust, and the Harvard Business School. Abigail has made a commitment to using global immersion as a way to equip the next generation of leaders with the empathy and insight needed to overcome twenty-first-century challenges.

Today, fewer than 1 percent of American college graduates have ventured beyond the wealthiest environments to meet any of the world’s 4 billion people living on less than $3 a day, according to the Open Doors report sponsored by the U.S. State Department. Without firsthand experience with the global majority, how can American leaders possibly expect to lead with global skills and insight?

Early Journey, Lifelong Commitment

When I was sixteen, my sense of self and the world was blown open when I spent a summer in a rural Nicaraguan village. Living with a host family, I learned to speak Spanish and make tortillas by hand, spent my days working in the fields, and taught English in the community’s schools. And while my motivations as a do-gooder high school student were initially to provide some form of “help” to a community plagued by material poverty, it didn’t take long for me to realize that my hosts were far from victims to be pitied. Instead, they were resourceful, persistent, and better attuned than any well-intentioned foreigner to what was really needed to lift themselves out of poverty.

Energized by my first experience working abroad, I called the Peace Corps to see if I could join when I graduated from high school. When I was told to call back in four years, I was struck by the incredible irony that our country allows young people to wield a gun in military service at age eighteen, but requires a college degree or significant work experience to join the Peace Corps.10

I was determined to find a way to continue learning from the world. Without these experiences, how could my higher education be relevant to life outside the classroom?

As an undergraduate at Stanford, my coursework focused on poverty, inequality, and international development. Always eager to test what I was learning in my classes in the real world, I took time off midway through college to return to my host community in Nicaragua and support them in developing their first library.

Armed with grant money and Spanish language books, I arrived in Nicaragua with what seemed like a simple goal: to help bring to life a community’s dream of building a library. What transpired, however, was far more messy and challenging than I could ever have imagined. Soon, I was the forewoman on a construction project in a culture and language that weren’t my own. The daily obstacles ranged from navigating political faultlines to secure the permits for our new construction site, to waiting for days on end for the rains so that we could mix the cement foundation.

My learning that year was incalculably more valuable than anything I had gleaned in a classroom. The experience was so profound that it left me with a question that I’ve now spent my professional life trying to answer: how different would the world be if every young American had experiences like this?

Years later, after a decade spent working across the nonprofit sector in the United States and abroad, I found myself increasingly disillusioned watching good intentions and resources fall short in the face of intractable social challenges. It was when one boss told me to rein in my ambition and begin to “think smaller” that I realized I needed to go to business school. With my vision for using education to drive social change on a global scale squarely in mind, I hoped to learn how to build a high-impact enterprise where “nonprofit” would describe our tax status, but not our management style.

Global Citizen Year Is Born

Just before graduation from HBS, I entered the Pitch for Change competition—an annual event that features the most promising new social ventures from around the world. With an impassioned elevator pitch, I proposed something outrageous: that someday, every American student would have an opportunity to spend a “Global Citizen Year” working in the developing world before college.

When I won first prize in the competition, I was shocked and humbled. Most important, the experience served as a critical moment of commitment. From the excitement in the nine-hundred-seat Burden Auditorium, I could tell that this wasn’t just my idea anymore; instead it was a vision that had resonance far beyond me. In that moment, I realized that my calling as a leader is to help catalyze a transformation in how America prepares its young people for effective leadership in our globalized world.

We all have a sense that today’s youth have not been well prepared for college or for a twenty-first-century global workforce. The statistics are striking. Fewer than 9 percent of anglophone Americans develop fluency in another language (compared to 54 percent of our European peers), and just 1 percent study abroad (and of those who do, two-thirds don’t venture beyond Western Europe). In a world where economic recession, climate change, and poverty transcend geopolitical boundaries to affect us all, how can we possibly expect to overcome these challenges if we can’t work effectively—and collaboratively—across borders?

One year after graduating from HBS, I had raised over $1 million from leading venture philanthropists—individuals and foundations looking to maximize the social return on their early investment—to launch Global Citizen Year. I built a founding team, and together we launched a pilot program with an inaugural cohort of Fellows—young people from across the United States who had the courage to buck the cultural pressure that moves our youth straight along the conveyor belt from high school to college. Instead, each deferred admission from schools ranging from Harvard to Evergreen State, with the aim of taking their education into their own hands and out into the world, then starting college the following year with a clearer sense of purpose and a more global perspective.

Our founding Fellows came from diverse geographies and varied socioeconomic and cultural backgrounds, but they were united by their passion and potential as leaders.

In September, as their friends were heading off for their first weeks in college dorms, our Fellows came to the Bay Area for our inaugural U.S. Training Institute. We introduced them to leaders across the public, private, and social sectors, and helped them develop a framework for understanding the experience they would soon embark on overseas. During the U.S. training, the Fellows had to reflect on two core questions that would help focus their learning objectives in the months ahead. The first was external: What are the causes of poverty? What approaches are most effective in improving peoples’ lives? The second was internal: What is my authentic style as a leader? Who am I when I’m so far from my comfort zone? What is it that really makes me happy? While these may seem like obvious questions for a young person, for the most part, this type of inquiry is systematically excluded from the conventional high school and college curriculum.

From here, our Fellows traveled in teams, each guided by a youth development professional we hired and trained to be a “team leader,” to their country posts in Africa and Latin America. The first month was in an urban center where the group members acclimated to their new context while engaging in an intensive language immersion and cross-cultural orientation. Next, the Fellows moved to more rural communities, where they were paired with host families and apprenticeships—work placements that matched their interests and skills with the needs of the community.

In Sengalkam, Senegal, an aspiring doctor spent a few days a week shadowing a traditional healer, and the other days working in a public pharmacy and a private clinic. In Seibkotone, Senegal, another Fellow revived the school’s library and unpacked the box of U.S. government– donated computers that no one knew how to set up. A few weeks later she was holding workshops to teach teachers to use Google and Wikipedia for the first time. In Santo Tomas, Guatemala, another Fellow worked with a women’s group on nutrition issues, and supported the development of a community garden.

Our Fellows had netbooks and flipcams, and throughout their experience corresponded regularly with K–12 classrooms and communities in the United States. Stateside, as interest in their work grew, we helped ensure that our Fellows’ experiences touched the lives of their parents, peers, and a broader public through partnerships with Current TV and op-eds in the Huffington Post and New York Times. A change of mind-set may begin with our Fellows, but ultimately, we hope they will create a ripple that reverberates across America.

In May 2010, our first class of Fellows returned home—transformed in their sense of themselves and the world and hungry to start their college careers. They spent the summer sharing what they had learned about their guiding questions through presentations in classrooms, blog posts, and publications in their hometown papers. In the fall, they headed off to colleges across the country, having developed the passion and perseverance that make the difference in college, careers, and life.

With this first year’s success, my vision is emboldened and we are now on track to triple the size of next year’s cohort, with the aim of engaging ten thousand Fellows annually by 2020. We are working to do more than build another exchange program—our aim is to catalyze a movement that engages colleges, companies, governments, and social enterprises around the world.

As our effort gains momentum, Global Citizen Year can fundamentally restructure the way young Americans learn about and engage with the world. By supporting emerging leaders at the moment they are most ripe to new ideas, growth, and exploration, we can awaken their true potential. Our Fellows enter college knowing what they want to pursue, why, and how to use their education to have an impact in business and public service—for our nation and our world. Over time, we will build an undeniable force: a pipeline of new American leaders with an ethic of service, the fluencies needed to communicate across languages and cultures, and the ability to work at the interface of the public, private, and nonprofit sectors to build a more peaceful and prosperous world.

Broader Lessons for Business Leaders

At its core, good leadership requires empathy, and empathy requires firsthand experience. If we aspire to develop global leaders, then we must also understand the breadth and diversity of experiencing people, places, and problems that we won’t otherwise experience if we stay close to home.

As Global Citizen Year prepares the next generation of leaders, American corporations can—and should—be equipping our current leaders with the empathy and judgment they need to make effective decisions in a globalized world. Following the lead of programs like IBM’s Corporate Service Corps, a growing number of companies have developed programs that enable employees to live and work in the developing world as a means of learning about new markets, building internal capacity, and supporting employee retention. But this kind of experiential learning must become the norm, not the exception. GE should send product designers to rural communities to truly understand which technological innovations are—and are not—appropriate in improving lives at the bottom of the pyramid. The Gap should send product managers to work in the plants where their clothing is being produced.

Not until we walk in another’s shoes can we truly feel others’ hopes and fears, and have the wisdom to know what it would mean to work together toward a common cause. One day, we will have redefined effective leadership training to include firsthand knowledge of people, languages, cultures, and solutions that can only be found beyond our borders. Simply put, we can’t afford not to.

The Business of Reconciliation

How Cows and Co-Ops Are Paving the Way for Genuine Reconciliation in Rwanda

CHRIS MALONEY works as a management consultant on projects for public and private sector clients across Africa, especially in agriculture, health care, and policy. A native of New York, he holds a BA in economics and African/African-American studies from Stanford University, and both an MPA/International Development and an MBA from Harvard University. In reflecting on his experience in Rwanda, Chris realizes how unfamiliar environments abroad can lead one to reevaluate traditional notions of business risk and social return.

It was late at night, and I was tired. Perfect timing for my inner consultant to become narrow and critical. I had come up to Rwanda to look at ways in which the main agriculture challenges in the country were being addressed by both the government and foreign donors. I was knee-deep in documents, sitting outside on a typically breezy, eerily silent Kigali evening. As I read through the reports, my mind started raising red flags on two programs in particular:

- The “one cow per poor family” program intended to get every poor family in Rwanda a cow—thereby increasing the amount of milk, protein, and fertilizer available to the average family, which sounded good on paper.11 But this was in the most densely populated country in Africa, where almost everyone was poor (living on less than $1 per day) and stuck on tiny hillsides. How on earth would this work? There were few people with the skills to care for the cows, little land for grazing, little land on which to use the new source of fertilizer, and little credit to allow the farmers to expand their farming activities once they had the cow—it was hard to see how this program could be sustainable.

- In the government’s action plan, the co-op approach seemed to be the main way of solving problems—a tough way to go.12 For farmers to move beyond subsistence, they need to be able to buy the right inputs to grow more and access the right markets to sell more. Co-ops are one way to do this (form a group to access credit for inputs and sell products in bulk), but they are notoriously messy and hard to sustain. There are challenges with misaligned incentives, poor leadership and management, and too many stakeholders. Individual entrepreneurs, on the other hand, were more what I was used to seeing in African agriculture transformations—individuals who would have private sector incentives to work with farmers to help them access inputs, and aggregate their output to help them access markets in bulk and get better prices for everyone. But such entrepreneurs seemed to figure only vaguely in the Rwandan government’s plans, and I couldn’t figure out why. Why take the riskier co-op approach?

My mind started to wander. As with everything in Rwanda, one cannot ignore the 1994 genocide, in which Hutus, the largest ethnic group, systematically slaughtered a million Tutsis in one hundred days under an extremist Hutu government. This led to the displacement of millions of Rwandans, both Hutu and Tutsi, before Tutsi rebels came in and stopped the genocide. This was a brutal time, involving machetes and constant fear, where friends and neighbors somehow switched off their humanity for four months. This hotel where I stayed—the Serena, Kigali’s main business hotel—was called the Hotel des Diplomates during this awful period. The Diplomates was the antithesis of the Hotel des Mille Collines, which was right down the road, and now famous from the movie Hotel Rwanda. As opposed to the Mille Collines, which had served as a sanctuary during the genocide, the Diplomates served as the genocidal Hutu government’s headquarters as the Tutsi rebels eventually closed in on Kigali. It was here at the Diplomates where district governors of the Hutu extremist government were ordered to update the ministers on how fast their “work” was progressing—that is, killing all the Tutsis in their home regions—and where many grisly executions were carried out on the top floors. But now, sixteen years later, I couldn’t even fathom such a thing. The hotel had since been bought, gutted, and transformed into a modern facility that could have been anywhere in the world. Today the place was sterile, and it was comfortable. And just below this shiny surface, it was filled, like everything in Rwanda, with the ghosts of the past.13

How does a country begin to put such spirits to rest? Perhaps, amazingly, the way the government was going about its agriculture transformation activities was one such way. As I thought about these programs, and as I pressed for more feedback in interviews with various people around Rwanda over the subsequent days, I realized that both the cow program and the co-ops were trying, perhaps, to use business as a means of reconciliation. To me, it was a startling idea.

Spending some time in the rural villages and meeting with farmers themselves painted the picture for me. After the genocide, many villages’ lands had to be completely reconfigured as many families had been killed, or fled, while other people, sometimes totally new, came to the village for the first time. In a few places I visited, genocide victims were given plots of land right next door to someone who had been a perpetrator of the genocide, thereby encouraging some form of reconciliation since they had to see each other every day. It was not easy. One woman I spoke to, who had lost most of her family, simply said, “It’s very hard, but he is my neighbor.” How does one rebuild in a setting like that? It was here where I began to see that the cow program had a part to play in this story. A program rule in many places was that the first calf of the cow must be given to a neighbor. In this way, the cow program was not just a subsidy or “gift from the government,” but rather an asset with a strong future value that brought neighbors together and gave strength to families where so much had been lost. This gift of the first calf was incredibly significant. A cow, it turns out, can often provide a family with just enough cash to access higher education, and have a steadier, more diversified diet, among other benefits. As I began to understand it, the gift of a cow could change lives, as it would work across families, and help, in some small way, to aid in reconciliation—if nothing else, it would certainly help bind neighbors together.

Rebuilding communities was the other big challenge. The fractured villages needed something to pull them together—not just at the family-to-family level (as was being done with the cows), but at the community level. This is where the co-ops came in. As tough as they are to build, manage, and sustain, the role of co-ops in a Rwandan village was more than just helping farmers improve their income. Looking closer, I saw that the co-ops would give farmers a common sense of purpose, an incentive to want to work together and achieve a positive outcome. A co-op changed the lives of farmers economically and socially. It could be a critical tool for pulling a community together and provide an incentive for it to rebuild itself. It also avoided the appearance of favoritism. If the government was seen as supporting one individual entrepreneur over another in some of these places, the fractures in the community could grow. But the co-ops could avoid all of this, as they would first pull the community together, and maybe at a later point spur more individual entrepreneurship.

Stepping back, I realized the co-ops and cows were important in ways that no IRR (internal rate of return) or competitive strategic analysis could measure. I learned that, as with so many things in Africa, the context was everything. It is hard to put a number on the “value” of reconciliation, but it is here where measures like social return on capital and deeper cost-benefits would be critical. Indeed, the amount of effort that would be needed to make “one cow one family” and the co-ops work would be high, but the value it could create was socially tremendous, and something I might have missed had I not gone into the villages themselves, or thought more deeply about the programs’ unspoken motivations. You wouldn’t see any explicit reference to reconciliation in the dry, official policy document. Instead of thinking of the cows and co-ops as too risky, in fact I realized it was this high amount of risk that could possibly guarantee a very high return—one that went far beyond monetary value, but helped families confront the horrors of the past, and reconcile entire communities.

For me, the lessons from this experience are twofold. First, business can be used to create incentives not just for economic return, but also for social return. This is happening all over Africa and across the world, but Rwanda was the first place I saw business used as a cornerstone of such broad social transformation. Second, it is not always easy to see this idea of “social return,” nor is it easy to quantify. The risks of “social business” are high, and likely require some economic cost to capture the value of increased social return. Efforts need to be placed on understanding how to mitigate these risks to maximize the social return, and shed new light on what might have originally been a questionable business case. For young managers seeking to grow global careers, this implies several things:

- First, working in environments completely different from the ones you are used to requires you to push harder to understand the context and keep an open mind. Though difficult, you must think through the project from the point of the view of “the other side,” looking at all the players’ motivations and incentives, or else you might miss the whole point. No one ever explicitly told me these projects were about reconciliation—my realization came through getting out into the field and interacting with a range of people, from individual farmers to political and social experts. What would the government want? A country put back together and moving forward. What did the villagers need? A stronger social fabric and a way to start lifting themselves out of poverty. Using this lens, I began to see how these projects were using business to achieve such outcomes.

- Second, because projects in areas with profound social challenges may have positive externalities that are hard to quantify, the process may be as valuable as the end product. While the programs are rolled out, the “cow annuity” and the small businesses formed by the co-ops bring families, neighbors, and communities together. Therefore, when weighing the risk of a particular project in such a situation, one must consider all of the possible effects that might come out of the process of implementing it—and what might happen if it is not implemented. This then needs to be weighed against what the project will ultimately create, to see if the trade-offs between the various costs, risks, and returns are worth it.

- While perhaps stating the obvious, when you work in socially troubled areas, there is a high risk of failure. Alternatives to achieve the implicit outcome (in this case, reconciliation), as opposed to just the explicit outcome (income generation for poor farmers), should be explored up front, to see which approach makes the most sense. From the cows to the co-ops, many of the programs I saw in Rwanda are risky and difficult to implement. But the social return I believe is worth the risk, and we need to shift the focus to ways to increase the likelihood of success and to solve the execution problems during roll-out.

What I love about working in Africa is that I am constantly reminded that I don’t know what I don’t know, and that with every project there is something more to learn, a new perspective to add to my toolbox as I work on various projects around the continent. In the end, I cannot guarantee the cows will turn Rwanda into the next Wisconsin, nor can I guarantee that every co-op will run smoothly. However, I do believe that the process of working through this venture can help put many of Rwanda’s ghosts to rest.

INTERVIEW WITH . . .

Dominic Barton

Global Managing Director of McKinsey & Company

Dominic Barton talks about his own global experience, what globalization will mean to organizations and young leaders, and how businesspeople can use global experience to improve themselves and their organizations.

As a firm with a global footprint, McKinsey has nurtured an organization that cuts across cultures and boundaries. How have McKinsey and its clients responded to globalization over the past several decades?

In the late 1950s, we began to help emerging multinational companies expand their presence in Europe, South America, and parts of Asia. We also began hiring global talent (at some scale) in key universities in the U.S. and Europe. This helped to set us up for globalization over the next fifty years. Over the past several decades we have broadened our geographic footprint (now fifty-five countries with the opening of our Nigeria office in November 2010). In fact, McKinsey—and many of our clients—have responded to globalization by expanding physical presence to where demand opportunities are in key geographic nodes around the world and by becoming locally relevant in each of those nodes. We have also pursued a global or “one firm” culture—a common standard across geographies for our client service approach (e.g., all clients are clients of the firm and not the local office—we serve our clients with global teams and bring to each of them the most relevant parts of our global knowledge); global training; one language; our talent development approach (e.g., all partners are elected globally and have been from the beginning; a strong encouragement of mobility between countries throughout one’s career—I have personally lived in seven countries on all major continents while at McKinsey), which encourages a global perspective; and our remuneration approach (e.g., one firm global profit pool).

In your experience, how has globalization affected the careers of today’s young managers? How is this different from the previous generation of managers?

Managers today are playing and need to be equipped to play in a significantly larger, more diverse—but interrelated—and fast-moving playing field. They need to understand the broader world context in which they are operating—rather than just their immediate surroundings. This applies not only to new potential “demand” markets, but new sources of supply, innovation, and talent. For many, if not most, industries, disruptive change and innovation is as likely to originate from across the globe and adjacent businesses as it is in just the local market, and managers will need a wide field of view that includes deep awareness of global trends. Technology has a role to play in making emerging managerial challenges easier. There are also new decision-making and oversight skills to learn to ensure that the challenges associated with globalization and increased volatility and risk are met.

Young managers will also need to be much more versatile and mobile. Of course, overseas “chapters” in a career will be a much more prevalent part of career development for a far greater portion of leaders than in the past. However, versatility will need to go much farther—including the ability to work more seamlessly across public, private, and social sectors. The challenges we see in a globalizing world (for example, job losses in developed economies) require the strong collaboration of business, government, and social sectors. I think that young mangers should seek out opportunities to work across those areas—in effect becoming “tri-sector” athletes over the course of a career—and some parts of the world do this more naturally, such as India, China, South Korea, and Singapore.

Finally, for all mangers, the bar for depth of knowledge and the ability to work across cultures continues to rise in a globalizing economy. It is not sufficient to be the best within a market or region. In today’s world, young leaders must have relevant expertise and skills in a multicountry setting.

In what ways does global experience early in a businessperson’s career help him or her become a better leader?

Global experience early in one’s career can be likened to a “leadership accelerator”—developing a broader understanding of cultures and of decision-making and team-building approaches, as well as the challenge of what can be built from a “standing start,” enhances leadership “muscle.” Global experience early on forces one to challenge basic assumptions—for example, what is important to customers; what is important to talent; how to get things done—skills that are important for innovation and improving performance anywhere in the world. These managers will understand the cultures and values of partners outside their home country—making them more effective in building relationships everywhere. They will also develop bonds with suppliers and customers that are much harder to achieve at a distance. I spend a lot of time encouraging CEOs to take their boards into emerging markets to see in-person the changes taking place. The earlier that businesspeople can get to grips with the communities in which their customers live, the more likely that they will successfully lead companies that serve those customers well.

There are broader macroeconomic benefits as well. Workers overseas often act as ambassadors for their home country—making connections and opening pathways for other business leaders in their home country.

What are the skills and experiences that managers and organizations should nurture in their young business leaders that will enable them to succeed in tomorrow’s global marketplace?

One of the most important, but least valued, skills is the ability to put oneself in the shoes of others. We have been living in historic times with continued—and often disruptive—changes from all sectors and all parts of the globe, creating a constant stream of new possibilities.

In this context, leaders should seek out experiences outside their own country to understand dynamics, trends, and approaches that could create opportunities and challenges for their businesses.

Cross-sector perspectives can also be very helpful. Retailing and technology, health care and telecom, banking and consumer goods are all examples of industries where connection and cross-experiences will benefit young leaders. Even today, many CEOs get a lot of value from connecting with leaders in industries unrelated to their own.

Young leaders also need to be constantly open to change—seeking and even stimulating continuous experimentation with new technologies, new products, and new business models. One of the hardest things for any of us to do is to let go of business models that have proven successful in the past. Leaders need a “healthy paranoia” that will keep them on a high state of alert for new possibilities. By constantly questioning assumptions and orthodoxies, we can avoid becoming too comfortable with past success models. As the rate of change in the world increases, leaders need to learn to do this even more aggressively than their predecessors.