6

Time and Place

“After hard work, the biggest determinant is being in the right place at the right time.”

– Michael Bloomberg, businessperson, politician, and philanthropist

In addition to Ethos, Pathos, and Logos, Aristotle discussed one more element overlapping the principles of rhetorical persuasion: Kairos, or the opportune moment. Kairos is the time and place when conditions are right to persuade. The context in which you deliver your argument. The when and the where.

The When and the Where

The concept of kairos underlies each step of the influence process. From the order of the process, to the communication medium, to evoking the right emotions at the right time, to the right time to make the ask, the principles of kairos have been evident throughout.

According to famed rhetorical theorist Dr. James Kinneavy, kairos is “the appropriateness of the discourse to the particular circumstances of the time, place, speaker, and audience involved.”48

Consider Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s famous “I Have a Dream” speech. Did you know he gave nearly identical speeches at least twice before? Prior to delivering his “I Have a Dream” speech in Washington D.C. in August of 1963, Dr. King delivered dream speeches, with large portions nearly identical, at Booker T. Washington High School in Rocky Mount, North Carolina, in November 1962 and at the Great Walk to Freedom march in Detroit in June 1963.

So, why was Dr. King's D.C. speech so powerful? Well, Dr. King had practiced delivering his speech several times, the where (at the foot of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington D.C.), the when (during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, which also corresponded with the 100-year anniversary celebration of the Emancipation Proclamation), and the who (the more than 250,000 supporters of the civil rights movement) were all opportune.

Another great example of the influence of time, place, and audience is late-night comedy programs like The Late Show and Saturday Night Live. They take that day's and week's news and make fun of it. The timing is perfect, and it is late at night when people are tired. When you are tired, your brain is tired, and its processing is slowed, your inhibitions lifted, and you are apt to find things funnier.

The show's place is great: in front of a live studio audience, who are often cued to laugh. The producers leverage this, often panning the audience to show they are laughing, which makes it more likely you will laugh along at home (remember social proof from earlier). The audience laughter tells you what you are watching is funny and that laughing is okay, even recommended. How important are these social cues? In lieu of live studio audiences during the pandemic, some late-night shows have added a laugh track, a technique used in comedies and sitcoms since the 1950s used to prime the audience to laugh. Late-night comedy takes advantage of the impact of kairos: the time, place, and audience to make their entertainment more appealing.

The Right Time

Timing can be everything. As you have learned, the four fundamental steps in the process build upon each other and need to be employed in a particular order. You must first build credibility and engage emotion because to demonstrate logic and facilitate action, you must be credible and able to connect with individuals to influence and persuade.

One of the first things you need to consider is if your argument is relevant to the time and situation. What are the norms? How are people feeling at that time? What is their mood like?

Take for example, the commercial by Pampers during the 2019 Super Bowl. The Pampers ad featured dads changing diapers, a nod to the changing times. But these were not any dads. These were John Legend and Andy Levine, whose band happened to be playing the Super Bowl Halftime Show. The ad was relevant for the times and the occasion.

Another consideration of time is urgency. Is there a deadline? Have you created an advantage to or need to act now?

In the previous chapter, we discussed the influence of urgency. Attaching time considerations to proposals creates a sense of urgency. Time considerations instill the need to act now. Think of the timers on infomercials or online sales like the Deal of the Day. Think of “Don't miss out” or “You better act now.”

How impactful is timing? Well, in one example, we covered the Linda problem in Chapter 3. Would you be surprised to know that answers changed with the time of day? Research indicates we are sharper in the morning and more creative at night. This is supported by studies on how corporate communication is received by analysts and investors, judges making decisions on cases, students perform in standardized tests, doctors and nurses taking care of patients, and aggregate twitter language. We are more positive, careful, thoughtful, and less likely to make mistakes in the morning. Keep this in mind when you are solving a problem for yourself or are matching this timing to the influencing strategy you are pursuing. If you are persuading someone to complete a creative task, save it for the late afternoon or evening if possible. However, if you are working through something complex and/or analytical, consider communicating the message during the mid-morning. Perhaps the only time that should be avoided is lunch time. Just ask the prisoners who had nearly 0% chance of getting parole shortly before lunch, only to see their early morning and after lunch peers have a probability of approximately 65%.49

If you absolutely cannot avoid optimal timing, then consider implementing a time-out. For long situations, multiple pauses are helpful, especially a pause before key information is provided or a critical decision is made. Other forms of leveraging this concept include taking a lunch break outside or at least not at your desk, going for a walk, or as we wrote previously, listening to your favorite music before a big presentation or test, rather than cramming until the last minute.

These are all examples of timing in a micro context. On a more macro scale, humans tend to be more motivated at the beginning of a pursuit by our progress, but as we near the end, we transition to become more motivated by reaching the end. So, for example, if you were motivating your team to complete a three-month project, during the first two months you might focus on what you have been able to accomplish; however, in the final month, you could spend more time focusing instead on how close the project is to completion and how much of an impact it will have.

The Forgetting Curve

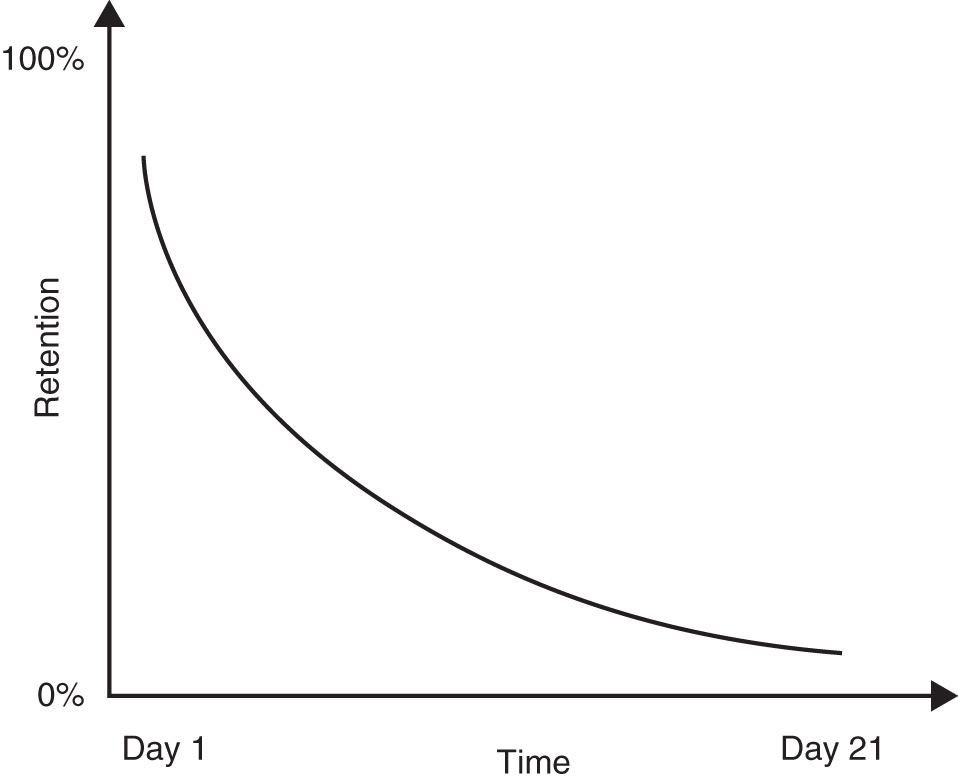

Another consideration related to time is memory. According to what we know about memory and the theory of the forgetting curve, memory, meaning retention, reduces with time. The longer it has been since you have been presented with information, the less you will remember it.

Of course, the complexity and amount of information matter to how long it will be retained. However, for complex, long, and drawn-out instances of rhetoric, information is likely to be lost before recall or decisions.

We have provided you with several tools to overcome the forgetting curve. One way to do this is to employ the summary close. In the summary close, you review the key benefits of your request or proposal.

To make what you say more memorable, you can also make it emotional. We are more likely to remember things we connect with emotionally. Better yet, you can use stories. Stories connect with emotion and are far more memorable than facts and figures. You should also focus on advantages and benefits of whatever you are pitching, to address what your audience cares about.

The Right Place

Choose the location in which you are attempting to influence wisely. To seize the opportune moment, you must choose the right place, or environment, which can have a big effect on your ability to influence or persuade.

The environment refers to the entirety of the location: the setting, the lighting, the noise, the ambiance.

There is no doubt the environment can set the mood.

Are you looking to create an informal environment? If so, meeting for coffee or lunch creates a more informal atmosphere.

Would a more formal environment suit the situation better? Meet in an office or conference room. Meeting at your own office is a power move. Meeting at the other party's office allows you the ability to come and go as you please.

Are you looking for an intimate setting, perhaps to build and nurture the relationship? Try dinner at a small restaurant.

The environment can be used to build credibility. Think about doctors who meet patients at their office where you see their degrees or a courthouse meeting where judges are elevated and behind a big desk, presiding over their courtroom.

Media Richness

Another aspect of “location” is the medium with which you choose to communicate. According to media richness theory, or information richness theory, different communication mediums (i.e. person-to-person, video call, phone call, text message, email) have varying levels of effectiveness conveying information.

For instance, richer communication channels allow you to communicate more information. Where person-to-person communication or a video call might allow body language, facial expressions, and tone of voice to provide richness to your communication, reports, texts, and emails do not afford the same opportunity.

Take sarcasm, for example. Detecting sarcasm in person is easier than when by written communication. Sarcasm relies on a number of cues, including facial expressions (rolling the eyes), tone of voice, and body language, but these cues cannot easily be conveyed in written communication.

On the other hand, if the information you want to convey is complex or highly technical, written communication may be a better option. Even if you are planning on communicating your message in person, you may need to be prepared with a written report, proposal sheet, or contract to convey complex information. Better yet, send an email ahead of time so the other party has time to review the information beforehand.

As you can see in Figure 6.2, it is all about picking the right medium for your message.

If you are wondering how much of a difference the medium makes, Daniel Balliet, Professor of Human Cooperation at Vrije Universiteit (VU) Amsterdam found that face-to-face meetings are 2.63 times more effective as a means of communication than written communication.50 So, how can you use your knowledge of media richness to improve your ability to influence? One thing you can do is to build relationships through more personal communication channels, such as in person or via video chat when face to face is not possible. Richer communication channels allow you to take in more verbal and nonverbal cues, get to know and understand the other party better, and form a deeper connection.

That said, there are times when other less rich communication can be more effective. For example, you send texts to signal responsiveness and have more frequent and informal dialogue with people. You email people if you want them to read and digest information prior to a meeting. This can be particularly useful when the subject matter is sensitive or there is too much information to absorb in one meeting. Email also works well to follow up and document what was discussed during a meeting and lay out the agreed upon action steps.

So, what is the rule of thumb? Generally, richer is better, but richer means more time consumption and less efficiency, so advantages exist to using other media in specific situations, the most common example being written forms to document or increase precision.

The Right Audience

Just as important as the right time and the right place is the right audience. You must understand and be aware of whom you are trying to influence and persuade. What is important to them? What messages will resonate with them?

To do this, you need to focus on the individuals. What are their wants and needs? What objections might they have? What is their body language conveying? What is their personality? What is your audience's mindset?

In the next two chapters, we will address more of the who. But, if you have been following the process thus far, you should have a good idea of your audience.

The Influencer's Toolbox

The Empathy Gap

Dr. George Loewenstein, professor of psychology and economics at Carnegie Mellon University, coined the terms hot-cold and cold-hot empathy gap in the early 2000s. It referred to the concept that humans are state dependent and, as a result, struggle to empathize with themselves and others in different states. He found that if we are upset, we tend to overestimate how long we will be upset and as a result make suboptimal decisions; for instance, say, we are angry our car has required repairs and we sell it, remembering shortly after we need a car to get to work. The same occurs in reverse; when we are in a good mood, we have a hard time understanding what it is like to be in a bad mood. An example of this would be smokers who, when not craving cigarettes, decide to quit but underestimate the difficulty to control the urge to smoke when their state changes.

This empathy gap is one of the many reasons the right time is so important for influencing, and this impacts both parties. The most powerful communication occurs when all parties are in sync and in the same state. This is why attending a rally, march, or sports home game is so powerful and even creates that goose-bump feeling. Almost all people there are sharing the same state and objective, and that creates a unique environment, which makes people particularly impressionable and persuadable.

Happy Endings

How you end an activity has a large bearing on how people remember it. Countless studies have shown how gifting a chocolate or mint at the end of a meal results in a larger tip. Elizabeth Dunn from the University of British Columbia found the same occurs with vacations. Make the last day of vacation great and you are more likely to have better memories. How something ends has a disproportionate and lasting impact on memory of the entire event. So, how do we use this when influencing others? Ensure to have a strong positive ending to your presentations and people will remember the entire meeting better. Or if you manage people, suggest they write down a few things they accomplished at the end of each day.

Putting It All Together

The Opportune Moment

Kairos is the idea of the opportune moment to influence and persuade, underlying the entire process.

The Right Place and the Right Time

The opportune moment all boils down to being in the right place at the right time.

- The Right Time: The right time refers to the relevance of your message to the time at hand and to the situation. To get the timing right, work through the Four-Step Process of Influence and Persuasion, building on the previous steps. You also need to consider how the individuals are feeling at that time. What is your state and the state of the party you are trying to influence? Keep in mind that the ending of a situation has a disproportionate impact on how it is remembered.

- The Right Place: Another important element of finding the opportune moment is the location and environment in which you will be influencing and persuading. The environment sets the mood. Pay attention to your communication mediums. The complexity of the information determines the richness of the communication medium through which you should converse.

- The Right Audience: Keep your audience in mind. Better yet, take the time to get to know your audience. The other people's state, their mood, whether they are a morning person or a night person, could all determine the opportune moment to persuade.

The Influencer's Toolbox

- The Empathy Gap: Understand that people are state dependent, and it can be a challenge to empathize with them and others in different states. Recognize the hot-cold state disparity and use it in deciding the time and place of communication.

- Awareness of State: Being aware of your own state and the state of others to help you determine when and how to best reach them. Your frequency of interaction with other people can also affect your ability to gauge your communication with them as well.

- Happy Endings: Know that how an activity ends has a huge impact on how it is remembered. If you end a conversation, meeting, or day with something positive, everyone will walk away with more enthusiasm about it.

End Notes

- 48. Kinneavy, James L. “Kairos: A neglected concept in classical rhetoric.” Rhetoric and praxis: The contribution of classical rhetoric to practical reasoning (1986): 79–105.

- 49. Danziger, Shai, Jonathan Levav, and Liora Avnaim-Pesso. “Extraneous factors in judicial decisions.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108, no. 17 (2011): 6889–6892.

- 50. Balliet D. “Communication and cooperation in social dilemmas: A meta-analytic review.” Journal of Conflict Resolution (2010) 54(1): 39–57.