Plan for Managing Your Retirement Risk

Moshe A. Milevsky, Ph.D.

Professor Richard Thaler from the University of Chicago and Professor Shlomo Benartzi from UCLA have devoted a substantial part of their careers to studying the financial mistakes and monetary blunders that people make in their daily lives. Apparently even smart people are not immune. These two researchers are leaders in the nascent field of behavioral finance, which argues that consumers are not cold, calculating machines that optimize their decisions in a rigorous mathematical fashion, but instead they adopt simple general rules for financial decision making, which often leads them far astray.

One of the most egregious behavioral “sins” these two researchers have identified is the tendency of too many Americans to allocate too much of their 401(k) plan—and even their own investments—to company stock. Apparently, more than five million Americans have over 60% of their retirement savings invested in their own company stock. Note that this is well after the notorious cases of Enron or WorldCom, where employees discovered the ruinous risks of such a myopic strategy. Even more surprising, ongoing surveys and focus groups conducted with these same employees indicate that they simply do not view this behavior as problematic. They think it is normal and healthy to invest in “things they know” because they can keep an eye on their investments. This optimism stands in contrast to the fact there is absolutely no evidence that employees have any superior ability to outguess the market or the experts regarding the performance of the stocks they hold and the companies they work for.

Many of the five million Americans who are engaging in this risky practice might be dead wrong. They are improperly investing their human capital and financial capital in the same economic basket, and their retirement might be at risk. Indeed, the evidence suggests that we have a long way to go before individuals truly consider the risk and return characteristics of their human capital and invest their financial capital in a way that balances their comprehensive risks. Hopefully, this book will help along this path. Remember, your 401(k) is a number, not a pension. It is up to you to manage and grow your nest egg so that it can eventually be converted and allocated into a pension.

Retirement Income Planning Is the Goal

At the university where I am a faculty member, I teach a popular 12-week course on personal financial planning to third- and fourth-year undergraduate students. During the semester, I try to cover the entire life cycle of financial issues, from cradle to grave. In the first few weeks, I spend quite a bit of class time on basic topics such as financial budgeting, managing credit card debt, coping with student loans, and so on. I usually get pretty full attendance and engaged interest during these early lectures. In fact, sometimes I get even more than full attendance from non-registered, yet interested students, who want to learn whether leasing is in fact better than buying a car, or whether ETFs are better or worse than index funds for the cost-conscious do-it-yourself investor. They are surprised when I preach that debt can be good. They absolutely resonate with my message that human capital is valuable and should be treated as an asset class to be hedged and insured. In fact, even the topic of life insurance appears interesting to them, perhaps due to some morbid curiosity.

Then, somewhere towards the latter part of the semester, as things are winding down around week number eight or nine, I get to the topic of pensions and retirement income planning. Here I tell them about pension annuities, as well as some of the demographic trends in aging. And, as much as it pains me to admit this, the attendance isn’t great for that lecture. I’m lucky if I get 60% of my enrolled students, and many of those who do bother to show up spend much of the time text-messaging, pod-casting, and whatever else they can do to pass the time. The following week, which is devoted to estate planning, is even worse. In fact—and I’m only half joking here—if you have some extra altruistic energy on your hands and want to take on a challenge, try spending time with a bunch of teenagers explaining the minutia of calculating Social Security payments early on a Monday morning, no less.

And to be honest, I can’t say I blame them. These kids are just not interested in retirement income planning. It is 40 years ahead of its time for them. To many of them that might as well be infinity. They are concerned with finding their dream job, getting rid of their student loan debt, and hopefully accumulating some savings. Even the topic of buying a home is distant to them. The pension is outside their realm of experience.

Yet, when I have the occasional chance to interact with students’ parents and grandparents, the situation is very different. When I mention that I also teach and do research on pensions and retirement income planning, I feel like the only doctor at an evening cocktail party. Everyone wants free advice.

In fact, the personal interest in pension matters extends to my academic colleagues at the University. Around the age of retirement all members of our pension plan must decide whether to take a lump-sum settlement and invest and manage it themselves, or whether to keep the money in the plan and instead receive a monthly income. Many of these professors have heard that I might “know something” about this issue and I get a steady stream of biology, chemistry, and engineering professors visiting my office for a consultation around the time of their big decision. They are wondering whether they should take the money and run, hoping to get a better deal themselves. (Interestingly, I don’t get many humanities professors. I’m not sure why.)

But yet, the topic of pensions is more than just a matter of demographic interest. When I pose the question to my undergraduate students—which retirement arrangement would you rather have, defined benefit (DB) or defined contribution (DC)?—most of them select the DC plan. Some of them justify their decision with some fairly persuasive arguments. They point out that they will likely be working for a number of different employers over the course of their life. Some of them will be spending time in different countries, or at least industries. Few, if any, believe (or even dream) they will be working for one company over the course of 30 years. They therefore need retirement savings with mobility and flexibility. Alas, a defined benefit plan with its rigid formulas based on years of service and final salary would make little sense to them. It is a relic from an industrial past. Indeed, this is likely why so many employees are content with 401(k) and IRA plans. The employer’s only responsibility is to contribute 5% to 10% of their annual salary cost to this piggy bank, and the employee is responsible for everything else. They take the risk and get the reward.

The statistics confirm this way of thinking. Many of the companies freezing or converting their defined benefit (DB) pensions and replacing them with defined contribution (DC) plans are doing so partly as a result of the demand from employees.

And yet, as the trends in aging continue to develop themselves out over time, the topic of pension and retirement income will only grow in importance. Remember that retirees face a number of unique financial risks that are not (as) relevant earlier on in life. Retirees face longevity risk, which is the uncertainty of their life horizon and its costs. Retirees face unique inflation risk.” Finally, they have to deal with a particular type of financial market risk, which has been dubbed the term sequence of returns. So, the risks are new and different and you will need a different strategy.

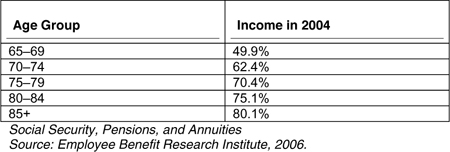

As you can see from Table 1, approximately 80% of the income being received by individuals above the age of 85 is longevity-insured. The remaining 20% of their monthly income might be exhausted prior to the end of their life. For younger individuals the percent that is longevity insured is even lower.

Table 1 What Fraction of Elderly Income Contains Longevity Insurance That Can’t Be Outlived? (Average for U.S. Population)

Step 1: Get a Retirement Needs Analysis

Obviously, boiling down the entire topic of retirement income planning into a 30-second sound bite is impossible. This is likely one of the most complicated calculations that an individual must make over the course of his life, and even the great Allan Greenspan has been quoted as saying this! That said, I can provide some general rules on how to think about this problem.

So, when you are ready to seriously think about the financing of your retirement, the first step is to sit down (perhaps with a financial advisor) and carefully estimate what you will need in retirement. Some people dismiss the importance of a formal written retirement needs analysis altogether. Or some confuse it with its close cousin—the retirement wants analysis, which is much more than your needs. Either way the exercise is informative. Add up the estimated annual cost of all the things you simply can’t live without. These can be items as basic as rent, electricity, and heating, all the way up to the annual cost of a golf club membership, or lease payment on the Mercedes Benz. Do your best to come up with a rough annual retirement needs estimate. Remember, though, it is a number that will not stand still. It is a moving target over time. This is because you will likely experience a higher and unique inflation during retirement. Either way, don’t move to the next step until you have this needs estimate. Also, remember these are your needs, not your wants.

Step 2: Determine Your Income Gap

The next step is to add up the sources of all of your retirement income benefits or guaranteed pension benefits. Start by getting your Social Security estimate and move on to any DB pensions you are entitled to from work. Make sure to differentiate income sources that are adjusted annually for inflation, such as Social Security and many state pension plans, from income sources that are not adjusted for inflation.

The difference between your retirement needs and your guaranteed retirement income is your income gap. This number can be $10,000 or $100,000 or $1,000,000 but is truly the most important number in retirement income planning.

For now, if 85% of your retirement income needs will be supplied by a Defined Benefit (DB) pension that generates inflation adjusted income, then you are hedged against most of your retirement risks. Stated differently, if your income gap is a mere 15% of your projected income needs, then you do not need to get any insurance or other forms of guarantees and protection. For many people though, an 85% replacement rate from pensions and Social Security, is not very likely. Refer back to exhibit 8.1 for a graphical illustration of this calculation.

Now, let’s move to the asset side of your personal balance sheet and the investment assets that are available to close the income gap. Presumably, you have by now converted most of your human capital into financial capital, which is your financial nest egg. Add up the value of the 401(k), 403(b), IRA, stocks, bonds, mutual funds and other investment-based (that is, DC) pensions. Anything you can and are willing to sell should be included in this calculation of wealth. At this point you should not include the value of your house unless you plan to sell, move out, and use the funds to generate your retirement income. For now, this is your “financial assets number.”

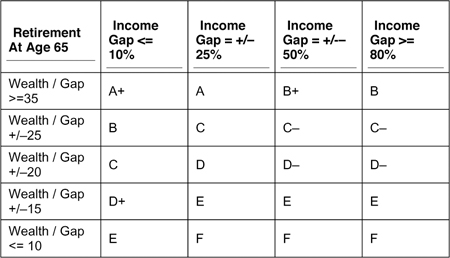

We are now ready for the big question. What is the mathematical ratio between the market value of your financial assets and your income gap? The larger the mathematical ratio is, the better your situation. For example, if your financial asset value is $1,000,000 and your income gap is $50,000, then your ratio is 20. But, if you have the same $1,000,000 in financial assets and your income gap is a higher $100,000 then your ratio is 10.

You will notice that so far I have not mentioned anything about your age, your gender, your marital status, or even your health. The calculation of the mathematical ratio between your wealth and your income gap doesn’t depend on any of these demographic factors.

Now you are ready for some general recommendations. Please don’t take this as investment advice, but rather as a blueprint for discussion.

Table 2 The Two Dimensions of Retirement Income Risk Management: How Much Wealth Do You Have to Finance Your Income Gap?

Grade Legend:

A: You are in great shape. Don’t worry about insuring any retirement risks. You can finance your income gap using a systematic withdrawal plan. However, make sure to invest your nest egg in a portfolio of diversified stocks and some inflation-adjusted bonds, and then periodically withdraw your income needs.

B: You are in good shape, although you might want to consider allocating a token 5% to 10% of your nest egg to protect against longevity risk, either using an immediate annuity or a variable annuity with a guaranteed living income benefit, especially if you are not willing to consider your personal residence as an eventual retirement income vehicle.

C: You should have enough, but you might consider allocating 10% to 20% to one of the many pension-like annuity instruments to help manage retirement risks, especially longevity risk. The exact amount would depend on the strength of your bequest motives, or how much of your financial estate you would like to leave to the next generation.

D: You are at the lower edge of income sustainability. This is where product allocation is most important and has the greatest impact. You should consider allocating 20% to 40% to annuity products with an emphasis on instruments that protect against longevity risk and the risk of sequence of returns.

E: It’s going to be very tight. That said, you might want to consider allocating 10% to 20% of your wealth to some sort of annuity instrument with insurance against longevity risk and sequence of returns, especially if there is no flexibility in your spending. You might want to delay retirement for a few years.

F: Not good. At some point during your retirement, you will be forced to reduce your standard of living. You should consider delaying retirement for a few years. Don’t try to gamble or speculate your way out of this problem.

As you can see from the table, for those retirees and near-retirees who have 90% of their income guaranteed from pensions plus Social Security, they don’t have to worry about product allocation or converting their nest egg into more pension income. Indeed, the billionaire Bill Gates does not need an annuity. He will never outlive his money, even if he doesn’t have a defined benefit pension from Microsoft.

Obviously, many variations exist on Table 2. Needless to say, if you are thinking of retiring at a younger age (say 60 or 55) then your investment wealth multiple—the first column in Table 2—should be higher in order to get a high grade in the safe region. Likewise, if you are retiring in your early or late 70s, you might not need as much. Also, if you are trying to protect a spouse and are planning for two people, then you should do these calculations jointly. Compute your total income gap and the total amount of assets to support that gap. Also, and just as importantly, there are health risks that go beyond the financial realm, which is why you should consider long-term care insurance, or at the very least learn something about it, so that you can talk intelligently about why you are not insuring against this risk. This is the beginning of a planning process, not the end. A new generation of retirement income products is now available. Figure 1 is just one indication that there is more innovation to come.

Figure 1 Innovation in the insurance industry

In sum, the money in your 401(k), 403(b), or IRA plan is just a random number. Hopefully it’s a big number, but by now you should know that it’s not a pension. That part is up to you. So, don’t let your fickle moods, fears, and phobias exert undue influence on the composition of your nest egg. Rather, use the unique nature and composition of your human capital to approach the management of your financial capital. Think and manage risk comprehensively, like the chief financial officer of You, Inc. Your future depends on it!

Endnotes

Benartzi and Thaler (2007) review the many biases that impact retirement saving behavior. They have collectively and individually conducted and reported on many experiments in behavioral finance and are two of my favorite authors and pioneers in this field. Belsky and Gilovich (1999) and Bazerman (1999) are two great and readable books on the systematic mistakes we make with money. Finally, Swenson (2005) and Malkiel (2003) are references for the individuals who truly want to embark on this journey themselves, with low costs, low fees—and no one to blame if something goes wrong.