13

Theories of Power, Dominance and Hegemony

Introduction

Power as an Analytical Variable in Politics

In Chapter 12, we have briefly dealt with the relationship between authority, legitimacy and political obligation. A point has been made there that a citizen's loyalty towards and identification with the authority is assumed because of inherent legitimacy and consent it carries. Political obligation is easily maintained in such a situation and those subject to it, i.e., the modern citizens, follow orders and laws emanating from the authority not merely due to command or force but by willing allegiance. When there is deficit in willing allegiance, it leads to legitimacy crisis and breakdown of political obligation. Authority is a form of power, which has a legitimate claim to exercise power. This means, power is legitimate when it has willing obedience from the citizens. Willing obedience comes only when it is recognized that the power being wielded is not arbitrary, personalized and unjustified or being used for selfish ends. Contrarily, it is generally perceived that authority is the power, which is being exercised according to the rule of law, impersonal order and is being exercised in public interest. Power without willing obedience is a brute force and can be sustained only through coercive means. If we agree with Green, then ‘will, not force is the basis of the state’ and hence, force cannot sustain power of the state for long. Thus, it appears that power must be legitimate and more so in a democratic set-up. It is accepted that power, legitimacy and authority bear relationship with each other. We will seek to explore the scope and nature of this relationship and how power is legitimized and what grounds are invoked. In modern democracies, authority is based on consent of the people who are considered as supreme source of power. German sociologist, Max Weber has discussed three types of authority and the grounds on which they seek legitimacy.

Since power is considered to be a crucial factor in politics and it is said, politics is about power, a survey of its meaning, theories and the relationship between sovereignty, power, dominance and hegemony will be in order. What are the forms of power and how different sections of the society perceive its distribution in society? How different forms of power—economic, ideological and political, related and how they affect authority and its legitimacy? What is the nature of power distribution in different systems, capitalist, socialist and developing? Liberal theorists would argue that power is evenly distributed in society and manifests in different forms; a Marxian theorist would charge that power is a means of class dominance, while a feminist would insist that power in a male-dominated society is manifestation of patriarchy. An elite theorist unequivocally maintains that power distribution in society is shared by the elites, while a democrat scoffs at such an idea and would not settle unless it is agreed that power belongs to the people. A pluralist will be happy if different sectional interest groups are considered as negotiating for their respective power realms to decide resource allocation. An anarchist would associate power with force and seek to abolish any sign of force in society—religious, economic, political or administrative. In this situation of differing and often contesting views, what role power is play to in society and its development?

In political theory, power is also studied in relation to public decision-making, policy formulation, their execution, control and allocation of public and societal resources. In a political system and the structural–functional approach pioneered and advocated by Easton, Almond, Powell and others, it is suggested that to perform its output functions each political system does extraction, distribution or allocation and regulation or control.1

What power does a political system have to perform these functions? Both Easton and Almond agree that the political system has the power of ‘authoritative allocation of values for society’ (Easton) or functions by ‘means of the employment, or threat of employment of more or less legitimate physical compulsion’ (Almond). Significance of understanding the political system in this way is that the political system analysis too has its basic premise grounded on the assumption of power as the main ingredient of output functions.

Power is not only identified with the State or the political system for decision-making, policy formulation, extraction, allocation and regulation but also with the individual for capacity-building and personality development. Positive liberals and those who support grounds for a welfare state such as J. S. Mill, T. H. Green and recently, C. B. Macpherson have discussed about the power of individual self-development. Macpherson has differentiated between developmental and extractive powers. He has argued that for their own self-fulfilment and for translating the liberal democratic government in participatory democracy, individuals need to realize developmental power.2 Libertarian thinker, F. A. Hayek while distinguishing three different notions of ‘freedom’, has termed positive freedom as power to satisfy our wishes. Recently, Nobel Laureate and economist, Amartya Sen has argued that empowerment amounts to capability expansion of individuals so that life choices increase. For example, what choices are available if individuals are not educated, go without medical facilities, sanitation, drinking water and housing or for that matter are discriminated, based on criteria of gender. It brings the concept of empowerment of those who are marginalized. What does power mean in this context and how does public or societal power relate to this?

Conventionally, in political theory some thinkers have been identified with the power approach of politics. Kautilaya's Arthashastra, Machiavelli's The Prince and Hobbes's Leviathan are considered as treatises that have advocated acquisition, maintenance, application and use of power by the rulers or the sovereign. Marx's analysis of economic power has provided a powerful analytical tool to understand political process as an integral part of, and, in fact, a reflection of economic relations. A libertarian theorist, Milton Friedman in his Capitalism and Freedom has argued that economic power must balance political power and hence economic liberty should be treated as a prior condition of political liberty. Engels in his The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State analysed the evolution of ‘public power’3 (armed power of the State—police, jail, army, institution of coercion, etc.) and its association with the State as separated from the people's power. For Gramsci, Engels's agencies of public power are state apparatuses that provide means of coercion and stand in collaboration with the means of hegemony to help maintain overall dominance by the capitalist class. As mentioned above, Max Weber has dealt with the relationship between power, legitimacy and authority and has discussed about various forms of authority.

In the twentieth century, the power approach has been identified with various writers. Harold Lasswell views politics as an arena of Who Gets What, When and How in his book of the same title and Bertrand Russell has analysed the dynamics of power in his book Power: A New Social Analysis. Robert Dahl (Modern Political Analysis, Polyarchy) and C. Wright Mills (Power Elite) have analysed the group and elite power dynamics. In India, Pranab Bardhan in his book, The Political Economy of Development in India has analysed how ‘dominant proprietary classes’ play more or less the same role that Wright Mill's power elite play in America. In the field of international politics, writers such as Hans J. Morgenthau, Kenneth Waltz, Henry Kissinger and others associated with the realpolitik approach, advocate power as an analytical variable for understanding international political process. Is power a relevant and suitable analytical variable for analysing and understanding the political process? Concepts such as balance of power, power vacuum, power elite, power broker, power bloc, power hungry politician, etc. are used not only by academic analysts but also by average citizens. No doubt, power is a powerful variable for analysing and understanding the political process, more so when we study power in its various forms—supremacy, authority, dominance, hegemony and influence.

Many of the developing countries for long have been under colonial power. Kautilaya, Machiavelli and Hobbes had talked about acquisition and maintenance of foreign territory or foreign sovereignty. Kings and rulers used to make colonies and maintain their power over the subjects. Between the seventeenth and twentieth centuries, various Asian, African and Latin American countries were under colonial domination of the imperial powers belonging to Europe—England, France, Spain, Portugal, etc. When we say colonial power, what kind of power was that and how it came to dominate a vast territory of the earth? Was colonial power a manifestation of economic power or political power or ideological and cultural power, or a combination of all these?

Power

Power, Legitimacy and Authority

As our introductory remarks reveal, power is considered as an important analytical variable in the study and understanding of the political system and its processes. It is also important to understand the way institutions of the State exercise their authority and the circumstances in which authority faces legitimacy deficit and deficit of political obligation. This leads to protest against the policies and actions of the state. One may say that politics is all about acquisition, maintenance and use of power. However, what do we mean by power and how do we differentiate its various manifestations?

Power is generally understood as capacity to affect other's behaviour by some form of sanction.4 Sanction can be in the form of punishments and coercion or rewards and inducements. As such, power can manifest in the form of reward, inducement, pressure, persuasion, intimidation, coercion or violence. These are intended to affect the behaviour of a targeted person or groups or communities to achieve the desired result. For example, during the colonial rule in India, the government resorted to firing against the Satyagrahis in 1919 at Jallianwala Bagh (Punjab). This was an example of use of power as violence to affect the behaviour of those who were protesting against the Rowlatt Acts. Presently, in the Indian electoral context, media reports suggest that political parties resort to distribution of various material things such as blanket, sarees, dhotis, rice, money, etc. amongst the electorate before the elections to seek votes of the people or groups or communities or a section of them. This can be an example of pressure through inducement to produce favourable electoral behaviour. This material inducement constitutes not only undue use of power but violates the principle that the individual is a rational choice maker and should not be induced or influenced to vote otherwise. We must note here that pressure, material inducements, violence, coercion, etc. are external factors that affect the behaviour of the agent.

There can also be use of influence in the form of moral persuasion, as in Satyagraha, which affects behaviour. Gandhi differentiates between power as ‘brute force’ and power as ‘soul-force or truth-force’.5 Satyagraha or moral persuasion comes under the category of truth-force and should not be considered as either coercion or inducement. For Gandhi, Satyagraha is related to correctness of means to achieve any goal. To counter brute force of the colonial power by violent means was unthinkable for Gandhi. He insisted on moral persuasion. Use of moral persuasion to influence behaviour of another person or agency that wields power, does not constitute use of brute force but only truth force. In Gandhi's views, moral persuasion is an appeal based on truth and does not imply any external pressure or force.

Generally, power is understood as an external factor of affecting or controlling others behaviour. Max Weber defines power as ‘the chance of a man or a number of men to realize their own will in a communal action against the resistance of others who are participating in the action.’6 Realizing one's own will against the resistance of others, means achieving the desired objectives even though those who are the subject of application of the pressure resist. Weber's definition is characterized by use of power in a social relationship where one person or group of people possess power at the expense of others. This is a doctrine of a zero-sum power game. Power is exercised at the cost of others. In cases where two or more actors have equivalent power, then result will not favour either. Bertrand Russell corroborates this view when he defines power as ‘the production of intended results’. This means ability of a person or a group of persons to achieve desired results. This is power to achieve an outcome or intended result.

There can be another understanding of the concept of power. Some of the theorists such as Morton Kaplan, Harold Lasswell and Carl J. Friedrich have defined power in terms of relationship in which a person or a group of persons exercise control over others. While for Weber and Russell, power is power to realize one's will or achieve a goal; for Kaplan, Lasswell and Friedrich, power is power over someone. For example, binding decisions over some one means control is being exercised. Government has power over its citizens because its makes binding decisions. In political systems analysis framework, Easton and Almond's definitions of political system cited above also imply that power is a primary element.

Power is also differentiated from influence. Robert Dahl has made a distinction between power and influence.7 In his book, Modern Political Analysis, Dahl explains influence as relation among actors where intentions, preferences and actions of one or more actors affect the actions or intention to act of other actor(s). This means if action of one or more actors in a social situation affects the actions or intention to act of other actor(s), explicitly or implicitly, it can be said that the first set of actor(s) has influenced the second set of actors. When a binding decision is complied with or an intended result is achieved without use of violence, but by use of persuasion, inducements, controlled information, etc., it constitutes influence. Gandhiji's Satyagraha may come under the category of influence through moral persuasion. Persuasion can be through moral appeal (Satyagraha) or manipulation (by providing incomplete information) or inducements (monetary or material gains). On the other hand, for Dahl, power is exercised when ‘compliance is attained by creating the prospect of severe sanctions for non-compliance’. Power is related to threat or sanction or what Almond would say, threat of employment of more or less legitimate physical compulsion.

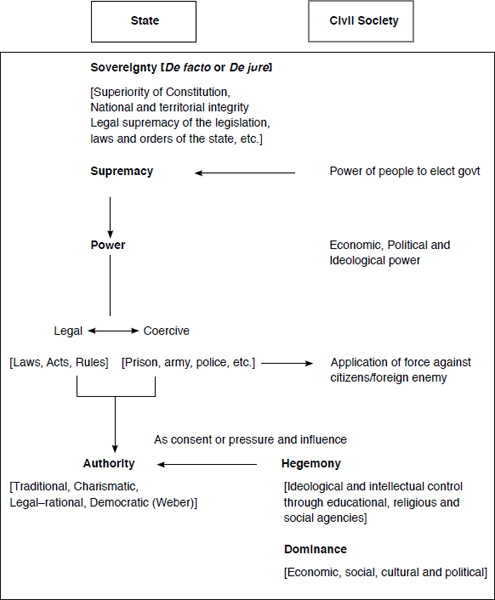

There are a number of concepts that are used in the context of understanding the dynamics of power. For example, sovereignty, supremacy, power, violence, coercion, force, authority, influence, dominance, hegemony, etc., are applied to describe various forms or manifestations of power. We have dealt with sovereignty in two chapters and have tried to discuss its meanings and implication. We can briefly touch upon the concepts in order to understand the context in which ‘power’ is related to them Figure 13.1.

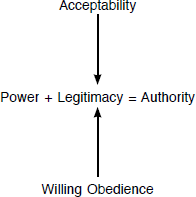

It appears that ‘power’ as a relationship between state and individuals, state and groups, groups and individuals, can manifest in various forms. However, the question arises, on what grounds, that are acceptable, it should be acquired, maintained and used. The relationship between power and legitimacy depends on its acceptability by the subjects and citizens. Acceptability of the use of power by the subjects and citizens depends on various factors. They include:

- Power is not exercised in arbitrary manner but within the framework of law, either constitution, rule of law or an agreed code of law.

- Power is not exercised for selfish and personal gains but for public interests and general welfare including defence, law and order, social welfare, etc.

- Power being exercised has been acquired through acceptable means and the holder has entitlement to it. This has been either based on divine rights and hereditary transfer (monarchies in England, Japan, Bhutan) on democratic consent (democratic governments in countries such as Indian, USA, England and others) or acquisition by justified revolutionary means (Lenin in Russia,1917, Castro in Cuba,1957, etc.).

- Power exercised is reasonable and not coercive and disproportionate to ends to be achieved. Colonial power or authoritarian power, for example are criticized for their use of excessive coercive power and are treated as unacceptable.

Power exercised according to these criteria is generally considered acceptable and acceptability results in willing obedience to power being exercised. If there is willingness from the subjects and citizens to follow and obey, power is treated as legitimate. Thus, power is legitimate when there is willing obedience and allegiance to its exercise and all its products—legislation, laws, acts, orders, rules, etc. are generally obeyed as rightful. We are calling it as generally obeyed because they are subject to a limit on political obligation and right to resist. Green's remark that ‘will, not force is the basis of the state’, should be understood in this context that power of the state is based on will of the people and not mere force of the state. In this way, we have the following equation between power, its acceptability, legitimacy and authority. When exercise of power is generally acceptable and its products willingly obeyed, power becomes legitimate. Legitimate power, we call authority (Figure 13.2).

By its very nature then, authority becomes an acceptable form of exercise of power, influencing behaviour of others for achieving certain ends or desired outcomes, or exercising control over others. Authority is automatically and unquestionably followed. However, there can be circumstances when influencing others behaviour may not constitute exercise of authority. For example, influencing by application of either excessive persuasion or coercion is not authority. As we have defined power, both persuasion and coercion are considered as a means of influencing behaviour of others. However, it may not carry authority. Heywood suggests that ‘Much of electoral politics amounts to an exercise in persuasion …’8 through campaign, rallies and meetings.

These are aimed at influencing electoral behaviour, as there may not be automatic and willing obedience towards a party's policies and manifesto. There is no ‘duty to obey’ a particular party unless there is political affiliation and membership that is either cadre-based or based on loyalty. In such situations, in the end it cannot be said that authority has been exercised because of two reasons: one, that electorates may not vote for a party or parties that exercised influence, and there is no duty to obey willingly. A second example can be cited of religious conversions. Arguably, it is felt that religious conversions do not always carry the authority of the religions converted to rather they are results of material and economic inducements. This means, if conversion is not a result of conviction of conscience of the person being converted, persuasion and influence in the form of inducement has been used. However, it may also happen that conversion is due to the exploitative and indignifying conditions being offered by a particular socio-religious set-up. In this case, an egalitarian and just order being offered by another religion will exercise authoritative influence. Thus, authority as an automatic and willing influence is distinguished here from influencing by persuasion and inducements. Influencing by coercion does not carry any willing obedience and does not constitute authority. Colonial or dictatorial power is often treated as coercive and devoid of authority.

However, it should be noted here that exercise of authority is dependent upon exercise of power. While power can be exercised with authority behind it, there cannot be authority with power behind it. While power is understood in the sense of power or ability to achieve a desired outcome by influencing others’ behaviour or exercise of control by one over the other, authority is right to influence or control. Thus, authority is the justifying means to exercise power. Authority, in short, is a form of power that carries rightful justification for exercise of power. Heywood while distinguishing between the two, suggests that while ‘power can be defined as the ability to influence the behaviour of another, authority can be understood as the right to do so’.9 He further adds that power brings about compliance through persuasion, pressure, threats, coercion or violence, while authority is based upon a ‘perceived right to rule’ and brings about compliance through a moral obligation to obey. In short, we can say that while power can be coercive either violent or non-violent, authority is always based on willingness of the subjects and citizens. In modern democracies, consent based representative governments are considered to carry authority. This is because their source of power is people's supremacy.

Besides democratically aggregated consent, there can be different grounds to justify power as legitimate. German sociologist Max Weber discusses at least three grounds. Max Weber, while dealing with types of authority, deals with the grounds on which authority is treated as legitimate. He categorizes them into traditional, charismatic and legal–rational authority. While the first seeks legitimacy on the ground of tradition, custom and religious and other beliefs and is characterized by hereditary transfer of power, the second is purely personal and depends on personal traits and charismatic and extraordinary qualities possessed by certain individuals that influence people. The third type of authority is based on impersonal order and seeks legal and rational ground for its justification. The authority that we associate with monarchies presently in Britain, Bhutan and Nepal, etc. according to Weber, would be traditional authority. The authority that people such as Mahatma Gandhi, Nelson Mandela, Mother Teresa, or for that matter, Lenin, Hitler and Mao carried would be charismatic authority. Weber identified ‘bureaucracy’ (as he defined it) with legal–rational authority. However, Weber does not discuss the authority that a Prime Minister or a President carries in a democracy. It appears neither traditional nor charismatic. Some prime ministers or presidents may be charismatic but the authority they carry is not charismatic. Primarily, their authority emanates from the people and hence we may call them popular authority or democratic authority. However, they do carry legal–rational characteristics such as working under the constitution of the country and the rule of law.

While Weber attempted to define legitimacy in terms of sources from which it is drawn, David Beetham in his The Legitimation of Power has sought to show that ‘power can be said to be legitimate only if three conditions are fulfilled’.10

The three conditions include: (i) power exercised according to established rules (formal legal codes or informal conventions), (ii) these rules to be justified in terms of shared beliefs of the government and the governed, (iii) legitimacy to be demonstrated by expression of consent on the part of the governed. Beetham's first condition is similar to that of Weber's criteria of established rules of the legal–rational authority. The second condition is problematic when we judge many rules that the colonial government formulated for the colonized people and have come to be accepted as shared. The third criterion is the basis of democratically elicited representative governments and democratic electoral process.

Suppose we have to consult the political masters of the past, and some of the present, as if we are asking them as to what bases and grounds they would like to attribute for power being legitimate and rightful (See Table 13.1). Can we attribute the following grounds on their behalf?

Table 13.1 Masters’ Grounds for Power Exercised Being Rightful and Legitimate

Dimensions of Power

When we associate the concept of power with political theory, we largely delve in the realm of political power. Concept of political power has been a matter of debate from early times. Plato in his Republic wanted to associate political power with philosophic knowledge lest, he feared, power would always be corrupting. When Lord Acton talked of power corrupting and absolute power corrupting absolutely, he was suggesting corruptible influence of power in the political realm. According to Allan R. Ball, political power is a key concept in the study of politics because it is associated with resolution of conflict. In the liberal view, political power and its distribution are assigned the task of negotiating, reconciling and resolving conflicting interests in society. Political power is treated as broker that performs the function of taking care of varied interests in society. Political power no doubt is an important dimension of power. However, there is emphasis on other dimensions of power also such as economic and ideological. This has been generally from the Marxian perspective. Another aspect of power that we may separately discuss is related to coercive power of the state. The last aspect is important to understand the power exercised by the State to coerce citizens and groups of citizens. Thus, a holistic analysis of dimensions of power requires analysis and understanding of political power, economic power, ideological power and coercive power. Legal power of the State is associated with political, coercive and ideological powers.

Political Power

Interpretation and understanding of political power differ in liberal and Marxian perspectives. In the liberal view, nature and characteristics of political power is related to how the political process is understood. In the Marxian perspective, understanding of the concept of political power is related to the understanding of the economic system. While liberal view treats political power as a mechanism of conflict resolution in society and hence, a neutral arbiter, the Marxian perspective holds political power as a means of domination and legitimation of the exploitative capitalist system and hence, an ally of the bourgeoisie. We can briefly discuss the two aspects.

In the liberal view, political process is treated as a means or mechanism of resolving conflicts through negotiation and reconciliation. Power that is implied in such a process is treated as political power. Conflicts arise on issues relating to distribution of resources in society, for example, welfare and material goods, reservation in employment and public offices, etc. or protection of religious, cultural and other identities. To resolve conflict through negotiation and reconciliation, the liberal view assumes that power distribution in society determines how this resolution is to be done. Allan R. Ball explains this when he says, ‘if politics is the resolution of conflict, the distribution of power within the political community determines how the conflict is to be resolved …’ He further adds that political power can be defined as ‘the capacity to affect another's behaviour by some form of sanction’.11 Balls definition gives a feeling that political power is available to the organs of the State or such agencies only that can exercise sanction, either as coercion or inducement. However, political power is exercised not only by organs of the state but also by groups of individuals, political parties, pressure and interest groups that participate in interest articulation and interest aggregation.

Political power is conventionally identified with the organs of the state that formulate and implement policies. This includes the legislature, executive (including bureaucracy) and judiciary. However, it is apparent that political power is related to various other agencies and organs in society. It is important to understand how power and influence are exercised by those who articulate and aggregate interests in society, on the one hand and, those who make decisions and implement them, on the other? Interests and pressure groups, media, social and political movements, political parties, on the one hand and legislators, executives and judiciary, one the other become two aspects of political power. Generally, political parties in a democratic set-up are considered as important channels of political power because they alternate in government and opposition. Pressure and interest groups also largely work through political parties and influence policies of the political parties or through them the government. For example, in India various trade unions work through their affiliation with parties of the left (AITUC and others with left parties), right (BMS with BJP) and centre (INTUC with Congress) spectrum. Other cultural and pressure groups, such as the RSS, also allegedly work through the BJP. Nevertheless, these organs and institutions also exercise political power.

Legislature, Executive and Judiciary are considered as formal organs of political power because they exercise the power of the State. On the other hand, interest and pressure groups and other influences coming from society are considered informal organs of political power. As such, political power can be understood by looking at the channels and organs that exercise the power of sanction and participate in conflict resolution such as the formal organs of the State and those which put pressure and articulate interests and influence the decision-making and resource distribution such as the informal organs.

Political power is overwhelmingly exercised by the formal organs of the State primarily because they have the source of sanction—means of legal and physical coercion (laws, acts, rules, legislations, police, para-military forces, prison etc.), redistribution of resources, welfare and other means of inducements. Traditionally, legislature enjoys the supreme power of legislation and is considered as repository of the people's power delegated to it. Executive is considered as the implementing arm of the legislature and judiciary as adjudicator and enforcer. We often discuss how power of office of the prime minister in a coalition situation is weakened vis-à-vis, a bipolar situation. This very idea refers to the limitation or restriction that the political power of office of the prime minister has undergone in a coalition situation due to weakening of party base. In another context, when we say that the prime minister is not effective in resolving the inter-state water dispute or is not able to negotiate with groups demanding regional autonomy, we are talking about the weakening of the political power of the executive vis-à-vis, the federal set-up. Political power of the State is exercised in a variety of ways, which include law enforcement, application of coercive means, inducements and welfare activities, resource generation and redistribution (e.g., tax collection and welfare activities), regulation (licences, permits, ensuring quality and standards), etc.

Participation of informal organs such as interest and pressure groups and political parties, media, etc. in negotiation, reconciliation and conflict resolution is without them exercising political power. Informal organs to influence the decision-making of the formal organs use pressure, persuasion, influence and intimidation and threat of physical violence. In political system analysis, while the formal organs exercise political power for ‘output’ functions, the informal organs exercise political power for ‘input’ functions. The fact is that output functions cannot be meaningfully performed unless input functions are carefully integrated within the political system. Political system analysis takes into account both formal and informal organs of political power as much as it accounts for the inputs, gatekeepers, decision-making and outputs in a networked manner.

Exercise of political power in this interrelated framework means study of power distribution in a society that manifests in a variety of pressure, influence and interest articulation. The liberal view of power distribution in society does not favour the idea of class domination. Instead, it assumes that power is distributed in such a manner that it is self-balancing. This means the liberal perspective views power distribution in society as if one aspect of power, say religious, is balanced by another aspect of power, say educational or economic or political. A classic example was provided by Max Weber, who in his essay on Class, Status and Party, identified, economic, social and political dimensions of power. Weber's multidimensional stratification analysis identifies various bases of power.

Liberal views on politics, political power and distribution of political power in society are interrelated. The idea of politics as resolution of conflict through distribution of power is a liberal interpretation. Bernard Crick in his book, In Defence of Politics has pointed out that Aristotle's Politics is a treatise, which celebrates this idea of politics as a means of reconciliation and conflict resolution. In the liberal view, politics becomes a process, which through distribution of political power seeks negotiation, reconciliation and resolution of conflicts. It becomes important for us to analyse and understand various approaches of distribution of political power within the liberal framework such as political pluralism, elitism, corporatism, etc. Pluralists would argue that associations and groups representing different interests in society should wield political power along with the state. Elitists argue that power is distributed amongst elites in society and the state negotiates with them, the corporatist view holds that certain groups such as the industrial interests, trade unions etc. are incorporated in political decision-making. We will discuss these perspectives on distribution of power in society separately in this chapter and compare them with class perspective of distribution of power.

In orthodox Marxian view, political power is a reflection of economic system and is not separate from class relation. While the liberal view treats political power as neutral arbiter, the Marxian view sees it as a means of class domination, political power is an ally of class power. In the liberal view, political power being a means of negotiation, reconciliation and conflict resolution is associated with piecemeal or incremental change. In the Marxian view, political power is to be taken over by the proletariat through a revolutionary means when the capitalist system is replaced with a socialist system. However, we can note that in a post-revolutionary society, communist party as vanguard, dictatorship of the proletariat and such other organs remain as organs exercising political power.

In the neo-Marxian perspective espoused by Gramsci, Althusser and Poulantzas, we find the political aspect being given almost an autonomous position though integrated with the economic aspect in the last analysis. This is related to how the political process is important for consciousness and legitimation of capitalism. Miliband in his book, Marxism and Politics, accepts that ‘Marxism as a theory of domination remained poorly worked out’.12 We will discuss Gramsci's theory of hegemony to find out how political arena and political power play crucial roles in stabilizing the capitalist system and maintaining its continuity.

We have differing views on political power as to who holds it. Conventionally, political power has been identified with the three organs of the State. The Lockean perspective's threefold division of power and Montesquieu's doctrine on separation of power, provide that legislature, executive and judiciary are important organs of political power. This is amply reflected, for example, in democratic constitutions of America and India. Max Weber's analysis of bureaucracy and subsequent development in the role of bureaucracy in industrial and democratic countries with a complex decision-making process reveal that bureaucracy wields political power as an integral part of the state organs. Political power as power of negotiating, reconciling and resolving conflicts arising on resource allocation and redistribution is considered as being exercised by various groups in a society which puts pressure on the decision-making of state organs. Elites, political oligarchy, ruling class, power elites, dominant classes and such other concepts have been employed to designate those who wield political power. Political parties and their leaders are considered as significant elements that mediate between the state and the social groups. In this, they wield political power.

Our analysis suggests that political power is not ‘the capacity to affect another's behaviour by some form of sanction’ alone, as Ball says. Rather it also means power of negotiating, reconciling and resolving conflicts arising on resource allocation and redistribution, which is exercised by various groups in society, which put pressure on decision-making of the state organs. Political power is understood in terms of how power is applied for negotiation, reconciliation and resolution of conflicts relating to resource allocation. This means when the State and its organs do redistribution and resource allocation, regulation of various actions of individuals and groups and extraction of material resources (taxes, fines, fees, economic benefits) for the benefit of the state and welfare, how political power is applied and how it is influenced.

Economic Power

Economic power is related to material and economic means of production, distribution and its regulation. Those who own the means to produce, control the market, supply and distribute goods and items wield economic power. The industrialists, rich agriculturist farmers, traders, landlords and the big business persons in financial and service sectors wield economic power. We have mentioned that the Marxian analysis focuses on economic factor as the key factor in understanding power dynamics in a society. Capitalists are the owners of the means of production, industrial establishments and financial and commercial interests. The Marxian analysis suggests that the class, which owns the means of production is the dominant class and state power is used to serve its interest. This means Marx associates economic power with dominance of the capitalist class. As such, the state and the political process in a capitalist society serves the interests of the bourgeoisie. It finds no separation between the economic and political interests in capitalist society. This can be rectified, Marx predicted, only when socialist means of production is established.

While in the Marxian analysis, economic power is associated with the capitalist class and considered as exploitative, libertarian writers such as F. A. Hayek and Milton Friedman have argued that any association between the state and economic power will be inimical to individual liberty. They have argued that economic freedom should be part of individual freedom and insist on elimination of any role of the State in controlling or directing economic activity. Hayek feels that state intervention, through planning and regulation in the economic field, imposes external criteria of choice and destroys individual liberty. Friedman also argues that economic and political power should never combine. Instead, he suggests that individual economic liberty provides a guarantee against any excesses of political power. In brief, the libertarian perspective does not want any economic control by the state and opposes state intervention in planning, regulation and direction of economic activity in society. The libertarian view opposes association of economic power with state and planning because it considers it inimical to individual liberty.

We are aware that state does interfere in economic activities. In liberal democracies, influence of positive liberalism and welfare ideas have led to state intervention in various aspects of economic activity to ensure fair degree of redistribution of material and economic benefits to all sections of the society. In many developing countries, the State has adopted a framework of planned and directed economic development. This has resulted in the state being owner of means of production and distribution. In India, for example, under the framework of Public Sector Undertakings (PSUs) and other commercial activities, the State is a large sharer in economic activities. Planning and central direction of the economy is one of the characteristics of the mixed economy that prevails in India. It is considered that the State wields economic power in two ways: firstly, through ownership of means of production and being a competitor and secondly, through regulation and direction of economic activities through licences, permits, taxation and export-import policies and fiscal, financial and agricultural policies.

Notwithstanding the debate on desirability and efficiency of state intervention in economic activity, it is generally agreed that some degree of intervention of the State will be required and is in any case necessary. The Nobel Laureate Joseph E. Stiglitz, in his book, Economics of the Public Sector has argued that there are at least ‘six basic market failures’ or conditions in which the market is not efficient. They are related to imperfect competition, public goods, externalities, incomplete markets, imperfect information and unemployment, inflation etc. He argues that ‘they provide a rationale for government activity’13. World Development Report, entitled The State in a Changing World recognizes role of the state in ‘addressing market failures’ including regulation, coordination and redistribution.14 Role of the State as such not only provides political power but also makes the State as one of the wielders of economic power.

In socialist countries, the State and the communist party under the dictatorship of the proletariat are supposed to direct the post-revolution economy. As a result, party bureaucracy of the communist party and state officials wield economic power, as the means of production is owned by the state. This was the case in erstwhile USSR and economies of the East European socialist countries. Many observers of communist states have pointed out that ownership of means of production by communist states resulted in privileged salary structure for the elite and bureaucracy. Tony Cliff in his State Capitalism in Russia has discussed about ‘state capitalism’ where surplus was being extracted by the state apparatus from peasantry for industrialization.15

In response to the Marxian position on capitalist ownership of means of production and concentration of economic power in the hands of the bourgeoisie, many observers have pointed out that in capitalist–industrial societies, means of production is not really owned by the bourgeoisie and economic power is not concentrated in the hands of a single class as Marx had described. Views of James Burnham and Raymond Aron are interesting in this context. Burnham in his The Managerial Revolution discussed the phenomenon of ascendancy of the managerial class in the production process. He argued that the capitalist–industrial economic system is characterized by separation between the owner and the manager of the means of production. This has resulted in managers exercising economic power instead of the capital owners. Raymond Aron, a political sociologist, argued that in a capitalist–industrial economy, the capitalist class does not own means of production. This is because ownership has become public and people and groups of people own shares in companies. Public holding of shares has changed the nature of ownership of means of production. While Burnham's analysis argues that ownership and control of capital are separated in the hands of two different classes, Aron suggests that ownership has in fact become public and individual ownership is disappearing. Ralph Dahrendorf in his Class and Class Conflict in Industrial Society has argued that link between ownership and control has weakened due to the development of Joint Stock Company and technological advancements. These are aimed at refuting the Marxian analysis of economic power as power of the capitalist class.

It should also be noted that Marxian theorists such as Miliband and Poulantzas have tried to debunk the theory of managerialism of Burnham and separation of control and ownership of Aron and Dahrendorf in the capitalist economy. Miliband in his book The State in Capitalist Society has argued ‘that in contemporary Western societies there is a dominant or ruling class which owns and controls the means of production’.16 Miliband has further observed that the dominant or the ruling class ‘has close links to powerful institutions, political parties, the military, universities, the media, etc.’ and enjoys disproportionate position at all levels. Miliband's position is that the economically dominant class in capitalist society enjoys organic link with various institutions and organs of power in society. Poulantzas, on the other hand, does not subscribe to Miliband's doctrine of organic link between the ruling class and social background of bureaucracy, officials in educational and military establishments and media, etc. He suggests that instead of a unified and cohesive nature of the capitalist class and its economic power, the bourgeois class is ‘fragmented’ in fractions such as capital, financial, commercial, etc. However, their common economic interest is protected and safeguarded by the state by means of acting as an autonomous entity and balancing the conflict and pressure amongst the fractions of the bourgeoisie. Analysis of Miliband and Poulantzas suggests that the bourgeois class, either as a homogeneous class or as different fractions safeguarded by the State, enjoys economic power. The myth of separation of control and ownership is refuted.

Notwithstanding differing views on the nature of economic power and its holders, it is obvious that particular groups such as the industrialists, agricultural proprietary class, traders and merchants, commercial and financial interests, wield economic power. Chambers and Confederations of industrial houses, Kisan Sabhas of agricultural proprietary class, lobbies and associations of traders and merchants wield influence on the decision-making of the government. This takes place in various ways such as lobbying, financial contribution to party activities, direct participation of members in political decision-making through representation, etc. In India, conventionally budget-making involves wide consultation with various industrial, agricultural, financial and commercial interest groups. It is generally understood that all political parties rely on financial contribution from business and industrial concerns for their party and electoral activities. In fact, many a times, the left parties in India whose policy excludes them from such a linkage have demanded state funding of the electoral expenses so that transparency between financial contribution by industrial and business houses to political parties can be tracked. Not only in India, but in UK and USA also, the undeclared financial contribution to political parties by business and industrial concerns has been a matter of debate and controversy.

Due to a variety of factors as discussed above, those who enjoy economic power do influence political power in the form of professional lobbies and pressure or interests groups. Political parties or even movements also represent many economic interests. During the movement for independence against the colonial rule, Indian industrialists and merchants supported the Indian National Congress in a large number either by joining the party or by providing financial support.17

The capitalist and the bourgeois class in India realized that for the development of domestic industries and enterprises in which rested their long-term interests, they should align with the national movement for an independent India. The capitalist class through its Bombay Plan, 1946 did agree that India should adopt a mixed economy framework with co-existence of public and private sector enterprises.18 They needed the Independent Indian state to protect them from foreign competition; provide basic infrastructural facilities such as roads, highways, railways, ports and docks, airports, hydel and thermal power generating units; make capital available through publicly owned financial institutions such as the Industrial Development Bank of India (IDBI), Industrial Finance Corporation of India (IFCI), etc. It would be a rare encounter when capitalist class in India would have argued against the state intervention and mixed economy after the independence. However, when the capitalist class found it in their favour and profitable to get integrated with outside world for market, finance and capital, raw materials etc. they pressed the Indian state for liberalization and privatization. One may argue that mixed economy was the need in post-independent India, while liberalization and privatization a requirement in today's integrated economy. However, the point being made here is that economic power does influence political decision-making.

Influence and pressure of the rich landed class—landlords before independence and landed proprietary class after independence, is visible on political power and decision-making. The landlords opposed land reforms’ efforts and a variety of pressures were created against the state action. Bipan Chandra and others have noted that during the 28 months of Congress rule in many states between 1937–9, ‘the basic system of landlordism was not affected’.19 After independence, zamindari abolition was equally opposed from all sides. The Indian state found itself insufficiently equipped to tackle zamindari abolition and a variety of ad hoc individual voluntarism was started. Vinoba Bhave, a Gandhian, started Bhoodan Movement, voluntary land donation and distribution movement, that aimed at appealing to the heart of the zamindars (landlords) for parting with lands voluntarily which could be distributed to the landless. We know the fate of the Bhoodani romanticism. It was amidst these manifestations of Gandhian romanticism that the Indian state had to apply its force and anti-zamindari acts to tackle the heart of the heartless landlords. It is not hidden that Jawaharlal Nehru's effort at agriculture cooperatives in the late-1950s was opposed by many landed interests including Chaudhury Charan Singh who subsequently became the leader of Green Revolution rich farmers. Many observers and writers have equated the economic powers of the landed proprietary class who benefited from the Green Revolution with that of the kulaks. Pranab Bardhan in his The Political Economy of Development in India (1984) has analysed how ‘dominant proprietary classes’, of which the rich landed proprietary class is a major component, influence government policies through a variety of pressures for subsidies and other benefits and concessions from the state for agricultural inputs (seeds, fertilizers, electricity, low interest rate finance, etc.) and outputs (Minimum Support Price [MSP]). Government's Food Security Policy (FSP) and food supply to Fair Price Shops (FPSs) networks is largely dependent on food and other related products.20 There is no doubt that economic clout of the rich proprietary farmers influence the agricultural and food policy of the Government. Bardhan argues that as a result of subsidies and grants by the State to the economically dominant classes, there is ‘consequent reduction in available surplus for public capital formation’. It means, to the extent the Indian state is unable to resist the demands of the economically rich classes for subsidies, concessions, grants, transfers etc. it would have no surplus left for capital formation and even welfare activities for the poor and the needy.

Our analysis above suggests that power arising out of a variety of economic sources affect political power of the State and its decision-making. A Marxian perspective will attribute political power and state's policy in capitalist society to the economic power of the dominant class. Liberal perspective finds multidimensional bases of economic power in society and hence each countering other, e.g., the capital owner, managerial class, public share holding, etc. In socialist societies, economic power becomes the power of the party bureaucracy and state officials. In developing countries like India, we find influence of the rich landed class and industrial interests on the state decision-making. At the same time, the State through planning and direction and public sector framework continues as one of the economic competitor. In brief, economic power and political power are linked in a complex but dynamic relationship of influencing each other.

Ideological Power

The word ideology seeks its origin from the French, idéologie (ideo + logy) meaning ‘science of ideas’. The French philosopher, Destutt de Tracy is said to have used the term ideology to refer to ‘science of ideas’ in 1796.21 Ideology is described as a set of opinions, ideas, beliefs and values that shape the thought, behaviour and action of a group of people or social class. Generally, an ideology is associated with ideas and thoughts of a particular social class but it enjoys predominance and is taken as if it is the reality. It is presented as an organized and coherent system of ideas, beliefs, values that exercise common acceptance as reality and form the basis of social, economic and political philosophy and programmes. Since predominant ideology is presented for mass acceptance, it can manifest in many forms. Noam Chomsky says that in the name of consent of the people, opinion is manufactured and is ‘manufactured consent’; Gramsci says that ‘common sense’ is hegemonic ideology and the Marxian view depicts ideology as ‘false consciousness’ for the proletariat.

Ideology provides basis for justifying the existing system or alternatively, provoking political action and social change. Ideology involves the following characteristics:

- Ideology refers to a set of ideas and beliefs presented in a coherent manner.

- It justifies the existing order by providing explanation for its legitimacy and creating a general view in such direction, or alternatively, aims at political action and social change to achieve desired order by questioning its legitimacy.

- The ideas that appear as part of ideology, are presented as the only reality.

- Ideologies become basis for political movements.

- We refer to bourgeoisie ideology, socialist ideology, fascist ideology to characterize a set of ideas that appear or are presented as political philosophies of different sets of political movements.

Ideological power flows from how ideology of a social class or a group of people become dominant and is treated by everyone as if that is the only reality. It is power, which a set of opinions, ideas, beliefs and values of a social class exercise in society. It is meant to convince people about legitimacy of the existing system and as such, ideology is status quoist, e.g. the bourgeoisie ideology. Alternatively, it also provides a basis for political action and as such, ideology can be change-oriented, e.g. socialist ideology.

Let us see how certain concepts and causes, that we all subscribe to, can be part of ideological power. For example, the concept of national interest is treated as if every citizen is a uniform beneficiary of everything that a nation owns, produces or distributes. In the Marxian view, national interests are nothing but the interests of the ruling class presented as general interests. Similarly, the government in democracy is presented as representative of the interests of all citizens. However, it would not require philosophic wisdom to decipher that most of the time it represents interests of only a section of people. There can be a variety of examples where specific beliefs, explanations and political concepts could be presented as if they represent the mass base.

Marx was categorical in associating ideology with the ideas of the ruling class. Marx and Engels in their book, The German Ideology dealt with the issue of ‘production of consciousness’ and ideological power. The famous statement appears as:

The ideas of the ruling class are in every epoch the ruling ideas: i.e., the class, which is the ruling material force of society, is at the same time its ruling intellectual force. The class which has means of material production at its disposal, has control at the same time over the means of mental production, so that thereby, generally speaking, the ideas of those who lacks the means of mental production are subject to it.22

The import of the statement is that the bourgeois class not only owns the means of production, industry, finance, capital and market but also presents its ideas as if they are common sense, public opinion and consent of the general mass. For Marx, ideological power lies in its capacity to mystify reality and present a distorted, manipulated and false picture of the material condition. Why does bourgeoisie need ideological power to mystify reality? The Marxian view suggests that a capitalist system has an irreconcilable class division and the two main classes, bourgeoisie and the proletariat, are engaged in a contradictory social relationship. To hide class contradiction and conceal reality, the present capitalism makes the state appear as a neutral arbiter and an agency of welfare of all people and market as an arena of equal opportunity. They delude the proletariat and mystify the true character of economic relations. Acceptance of such a system of ideas leads to false consciousness and until the proletariat fail to understand this mystification, proletarian revolutionary consciousness cannot be attained. Marxian analysis finds ideology and ideological power as a powerful instrument in the hands of the bourgeoisie through which they legitimize their class rule.

However, as Heywood suggests, Marx did not consider his own uncovering of the process of class exploitation, theory of proletarian revolution and socialist–communist society as ideology, rather treats as scientific law of historical development. In the same manner, as Marx portrays bourgeois ideology as manipulative, mystifying and false, one can argue that Marxism represents the same, at least when the socialist states under the party bureaucracy spread their own ideology. However, Marx differentiates between ideology and scientific truth and holds that historical materialism is a scientific theory and proletarian revolution, a historical necessity.

Gramsci pointed out that in a capitalist society, civil society and its institutions such as family, church, schools etc. produce favourable conditions for justifying the existing system. While the state uses its coercive power through police, prisons and military, civil society generates opinion and consent suitable to the continuance of the capitalist system. In political sociology, what we call political socialization, Gramsci describes as hegemony. As in political socialization, political traits and behaviour are transmitted to the next generation, in hegemony, institutions of the civil society spread the opinion, ideas and beliefs suitable to the capitalist system as if they are common sense matter. For example, in the educational system, grading as per merit points inculcate behaviour suitable to competitive aspect; familial emphasis on respect to elders and obedience prepares for political obedience and obligation, discipline in assembly line production; religious submission teaches submission to the state, capitalist. By inculcating and instilling such behavioural aspects, these institutions produce the conditions of production, discipline in assembly line production, competition, etc. Louis Althusser also supported the view but he maintained that ideological power is exercised by what he calls ‘The Ideological Apparatuses of the State’, such as church, political parties, etc.

The uniqueness of the orthodox Marxian analysis of ideological power lies in identifying ideological power with the ideas of the economically dominant class and not with philosophy, religion, tradition or morality. The Marxian perspective suggests that ideological power emanates from economic power and produces legitimacy for the system.

Some writers have analysed ideology in the context of emergence of totalitarian dictatorships and their official ideology. In the mid-twentieth century, Hannah Arendt (The Origins of Totalitarianism), J. L. Talmon (The Origins of Totalitarian Democracy), Carl J. Friedrich and Zbigniew Brzezinski (Totalitarian Dictatorship and Autocracy), Alex Inkeles (‘The Totalitarian Mystique’) and others have analysed how official ideology of Communism, Nazism and Fascism provides doctrinal basis for a totalitarian system.23

Official ideology provides doctrinal basis of controlling on thought and for exercising ideological power. In this context, ideological power is exercised through social control and control on thought and results in closed society. George Orwell's perceptive novel, Nineteen Eighty-Four24 portrayed the process of ideological control and introduced terms like ‘thought police’, ‘big brother’, etc. Karl Popper in his two-volume book, The Open Society and Its Enemies (1945) argues that ideology is used as a mechanism of social control and results in closed society.

Writers such as C. Wright Mills (White Collar: The American Middle Classes) Vance Packard (The Hidden Persuaders), Herbert Marcuse (One-Dimensional Man), and others have talked about influences and manipulative effects on human beings. Advertisements creating false needs, market requirements creating false and insincere expressions by individual, e.g., compulsive smile of the sales girls/boys at a sales counter etc. are examples of non-visible influences. They come to control thought and behaviour of individuals and overwhelmingly instil the idea that this is the only reality.

Our analysis above suggests that ideological power flows from how ideas, thoughts and beliefs are controlled and used. Official ideology, in fact is used to justify and control political power. The Marxian theory suggests that ideological power is an ally of the economic power. However, in totalitarian systems, including allegedly the communist system, ideological power is used to justify political power.

Two other dimensions of power that we have hinted above, legal and coercive power are by their nature and content, prerogatives of the state. The state and its institutions enjoy coercive power and power to legislate and enforce. The state is generally identified with coercive, legal and political powers.

Political Authority and Its Limitations

In a constitutionally limited state, political authority is generally related with legitimate political power. However, political authority, as in mixed economy or as Marxian writers suggest about the capitalist systems, may also wield economic power or seeks its power on ideological basis. Political authority may exercise its power by using its various dimensions—political, economic and ideological. Political power manifests in legal (e.g. laws, acts, rules, legislations), coercive (e.g. police, prison, military), negotiating and influencing, extracting (e.g. taxes, fines) and redistributing (welfare, social service, public goods) forms. Exercise of power in all these forms must be in a justified, reasonable and acceptable manner. Political power must carry legitimacy with it to be called political authority.

However, though theoretically distinguishable, in practice, power and authority go together. Generally, there cannot be authority without power, though there can be power without authority. This is because power can be exercised in a coercive and arbitrary manner without concern for legitimacy and willing acceptability on the part of the subjects. Nevertheless, there can be cases when authority is recognized but political power cannot be exercised. For example, in post-Saddam Hussain Iraq, political authority of the government is recognized but it is unable to exercise the same because various internal forces are not allowing it to translate the authority into political power. Notwithstanding this limitation on authority, it may happen that exercise of power may be arbitrary for a section or class of people without affecting the others. During revolutionary periods such a situation may arise, when a class perceived to be dominant or exploitative is subjected to power that is considered arbitrary and coercive only by that class and not by all subjects. Use of power may be termed as illegitimate or arbitrary by a class of people when it does not serve their purpose or go against their sectional or class interests. For example, insurgents, secessionists and regional autonomy groups in India charge the Indian state of using excessive power and violence against them. To protect the national integrity and internal peace, the state uses coercive power and physical violence. However, it may be termed as arbitrary and excessive by those who are affected. Thus, the dynamics between power and authority remains contextual. Political authority, many a times, is application of power only. One way of identifying political authority is to observe application of power, that is who applies power using political organs. Seen in this way, there could be problem in differentiating a democratic authority from an authoritarian one.

A more generic view of political authority could be to treat it as right to rule. Allan R. Ball succinctly spells this when he says that ‘political authority is the recognition of the right to rule irrespective of the sanctions the ruler may possess’.25 Obedience and justification may come due to religious sanction as in divine rights, or due to charismatic personality of the ruler as in Hitler, or Lenin or Gandhi even before assuming formal state powers, or rational–legal ground as in bureaucracy. Thus, authority may emerge from a variety of sources. German sociologist, Max Weber discussed three sources of political authority. His threefold classification of political authority includes traditional, charismatic and legal–rational authority.

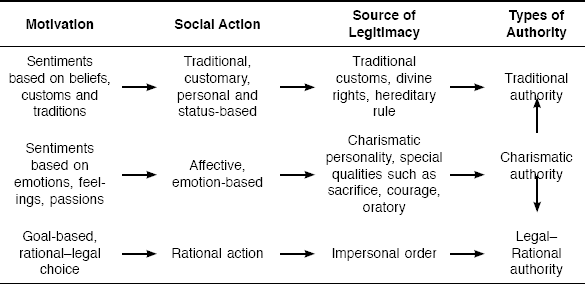

Weber's Classification of Authority

Weber has classified authority into three types based on how they seek legitimacy or which are the sources of legitimacy. His classification correlates right to rule with source of this right. For Weber, power is exercised either as control or influence. As such, it is a social relationship26 where control and influence is exercised through acceptance and willingness of those who are subjects. Weber's main conclusion with respect to authority is that power is institutionalized through acceptance and legitimacy. To ensure acceptance and legitimacy, Weber identifies three main sources, namely, tradition, personal traits and rational–legal order. It may be mentioned here that as sociologist, Weber is concerned with the nature of social activities, social relationships and the motivation behind it. He suggests that social action of a person can be based on either of the three types of motivation—habitual or customary motivation that results in traditional action; emotional motivation that leads to affective or emotional action and rational motivation which gives birth to rational action. Three types of social action by individuals provide three different ways in which the relationship between those who have power and those who are controlled can be expressed. One way of controlling or influencing others is to invoke tradition-based relationship; the second is to invoke emotional relationship and the third to appeal the legal–rational behaviour. Accordingly, we have traditional, charismatic and legal–rational authority.

Traditional action is guided by sentiments attached to belief, custom and tradition and accordingly, traditional authority seeks justification through these bases. For example, people had accepted that kings exercise powers as divine rights and they have a hereditary right to inherit this divine right. Political authority exercised by contemporary dynastic and hereditary rulers and monarchies are such examples, which are found in England, Saudi Arabia, Bhutan, Nepal, etc. Legitimacy and acceptance of the political authority is based on traditional relationship and tradition based motivation of the subjects. The authority is hereditary based on personal order and distribution of offices and this is based on personal, familial or status-based considerations.

Affective or emotional action is guided by emotions, feelings and passions and accordingly, an authority establishes a controlling relationship by appealing to these motivations. To do so, the leader or person seeking such authority must be capable of exercising such appeal. This requires a charismatic personality, exceptional personal qualities that attract people such as sacrifice, oratory, courage and heroic strength, or exemplary character, etc. Political authority is legitimized based on a charismatic personality and it generally arises in transitional situations such as revolution, defeat and subjugation, struggle for independence of a country, or an internal crisis such as a civil war or political emergency, etc. Generally, charismatic personality arises in the field of religion or politics. Charismatic authority commands followers, wields unchallenged power and undisputed acceptance. Some of the examples of such authority are Lenin who organized the Russian Revolution, Gandhi who organized massive mass movements against colonial rule in India, Hitler who emerged by invoking the post-Versailles humiliation of Germany and undue dominance of Jews in Germany, Mao who led the Chinese Revolution, etc. Basic features of charismatic authority include unorganized and personal authority; no hereditary transfer of power except for the same charisma being found in the next person; temporary and unstable authority, etc. However, according to Weber, charismatic authority can be transformed into either traditional or legal–rational authority. In case, sons/sdaughters or close relative inherit charismatic authority, it is transformed into traditional authority and is routinized through hereditary rule. If it is codified that whosoever possesses certain qualities as was the case in the charismatic leader, can become the leader then it is regularized as legal–rational authority. Weber cites selection of Dalai Lama of Tibet as an example of regularization.

Legal–rational motivation refers to goal-oriented and impersonal motivation. Rationality is related to the goal and the means to achieve the goal. A rational action is one, which seeks to achieve the goal or maximize it by choosing the best possible means. To this extent, neither personal charisma nor traditional beliefs and customs play any role. Rational action derives from an impersonal and rule-based order. The authority rests in the office not in the person that holds the office. We often use the terms, the office of the Prime Minister or the office of the President to denote that the authority of these functionaries emanates from an institutionalized and established office and though the occupants change, the office remains. Citizens obey the authority of the prime minister or the president not because a particular person occupies the post but because of the post itself, whosoever occupies it. However, it may happen that a particular occupant may introduce personalized behaviour and does not follow set rules. In this case, we say that the authority of a particular office has been de-institutionalized or has degenerated. The factor of impersonal continuity of the office despite personal transition is the significant feature of legal–rational authority. If neither charisma nor custom or belief provide the basis for legal–rational authority, then where does legitimacy come from?

As mentioned above, an impersonal order established by law, which separates the office from the office holder, is the source of authority. The impersonality of the order is grounded in:

- A set of official rules

- Written documents

- Hierarchy of offices

- Official position with duties and rights

- Division of work

- Fixed procedure for recruitment to offices

- Separation of the official and the personal

Through established order, officials draw their authority to use particular means to achieve set targets and goals. Impersonal order implies impartial and faceless decision-making. This means decisions taken or policies made are not based on considerations of personal or familial or sectionally-motivated interests, rather they are made irrespective of who is affected both positively and negatively. For example, office of the prime minister or the cabinet secretary in India may not formulate a policy that harms others but benefits them. We often use the term ‘faceless’ bureaucracy meaning that offices are important not the persons who occupy it, to pay tribute to Weber's conceptualization of a rational and impersonal order. As such, the source of authority is found in legal–rational order. Weber found that in contemporary industrial societies this process has emerged as the basis of organization of offices. He calls this process as ‘rationalization’. Weber's observation about bureaucracy is applicable in bureaucracy of the state. Due to welfare activities and complex modern policy-making and policy execution processes, contemporary states, are known for their huge and complex bureaucracies. Political parties, governments and political offices are all bureaucratically organized and run. Weber found this impersonal order as the source of political authority (see Figure 13.3). Constitution, rule of law, separation of powers and charter of citizen's rights are some of the elements that are source and limitations on political authority.

Legal–rational authority is the hallmark of contemporary democratic constitutions based on rule of law. We obey and respect political authority not because of their charisma or piousness, but because of their officiating within the framework of impersonal order, rule of law, legal–rationality set-up. When we say that the political authority has degenerated or has become corrupt, or is based on nepotism and familial and caste considerations, we compare their working with the Weberian legal–rational expectation. In fact, in many a transitional societies (transition from feudal to capitalist, colonial to independent, monarchical and feudal to democratic or socialist, etc.), transformation of traditional authority to legal–rational authority has been made possible with the help of charismatic leaders like, Lenin, Gandhi, Mao, Mandela and others. However, despite emergence of legal–rational authority in many cases, charismatic and traditional elements of motivation and social action remain there.

Andrew Heywood compares legal–rational authority with de jure authority and charismatic authority with de facto authority to denote legal backing for the first and lack of the same for the second.27 However, differentiation between de jure and de factor authority is a legal division and presents formal and informal aspects of recognition of power and may not capture the dynamics of sociological analysis done by Weber. In fact, authority can be identified with three different aspects—power, legitimacy and legality. Political power can be exercised as it is, without concern for either legality or legitimacy. Power during revolutionary transition, colonial power, power used by dictatorial and authoritarian rulers, power exercised by proxy, e.g., USA's power over Iraq presently, etc., are examples that fit in this category. Political power as authority requires legitimacy and Weber seeks to present sources of such legitimacy. Legitimacy in a democratic constitution is mostly based on consent of the people. The third aspect of political power is legal recognition, which is based on constitutionalism, rule of law and legislative recognition.

In India, we have manifestation and co-existence of mix of authority. For example, despite a well-laid constitution, rule of law, separation of powers and ‘faceless’ bureaucracy, it would not be uncommon to hear that people vote because of the charisma of a particular leader, or political reign should be handled by people belonging to a particular dynasty or family, or bureaucracy extends it help according to caste affiliations, etc. Politically, they are not wholly undesirable, but then what happens to modern constitutionalism? The phenomenon of giving titles to political leaders is a manifestation of recognizing charismatic elements in political authority. In India, for example, we have Mahatma (Great Soul—Gandhi), Lauh purush (Iron man—Patel), Loknayak (Leader of the masse—Jayaprakash Narayan), Durga Mata (Goddess Durga as Bajpayee called Indira Gandhi after the victory in the angaldesh War against Pakistan in 1971). At the top of it, we have a second versions of all this. Added to this, we still encounter a variety of Rajmatas, Ammas, Bahenjees, Chachas, Bhaiyajees, and others wielding political authority. We have a modern constitution, a Weberian bureaucracy, rule of law and a socialist, secular, democratic republic.

The apprehension and worry is that: are the two orientations in political authority in India—modern constitutionalism, rule of law and Weberian bureaucracy on the one hand, and charismatic and feudal elements on the other, contradictory phenomenon in India's republic? Is there hope of institutionalizing an impersonal order, rule of law and modern constitutionalism? Alternatively, Is India still a mix of tradition–feudal, charismatic and legal–rational political authority? Weber, of course, is no more to give us an authentic direction, but suffice is it to conclude that contemporary political authority in India does manifest a combination of all, at least at the operational level.

Limitation on Political Authority