3

Perspectives and Theories on the Origin of the State

Introduction

In Chapter 2, we discussed the concept and elements of the State, and the evolution of the State to its present form—the nation-state. In this chapter, we will study the various perspectives and theories of the State by taking into account rival and contested approaches that seek to find out how and when the State originated, its nature, its sphere of action, the roles and functions it performs for the society, its ends and objectives, and what is and should be its relationship with the individual.

We may argue that any enquiry into ‘political’ or ‘politics’ in contemporary times invariably deals with the State as the central operating agency, notwithstanding variations in the understanding and definition of what is ‘political’ or what constitutes ‘politics’. There is no denying the fact that we study the political aspects of non-state and supra-state actors such as regional and global organizations—NATO, UNO, ASEAN, WTO—as well as aspiring states like Palestine. Nevertheless, the logic and the concept of the State remain central.

Politics and the political process may apply to even institutions and processes prevalent in stateless societies, tribes, communities, clans, etc. Hence it has broader scope than the State. We have seen in Chapter 2 that the theorists of the political system approach—David Easton, G. A. Almond, G. B. Powell—suggest that any system, which makes resource allocation in the society in an authoritative and binding manner by use of threat or by use of (legitimate) physical force, qualifies as a political system. As such, the study of political system has a larger scope than the study of State. While this is true that politics of stateless societies can be studied through the political system approach, study of the State has been the main focus of political science.

The Greek words polis and politeia, which roughly stand for ‘city’ or ‘city-state, indicate a relationship between the State and politics. Plato's Republic was an enquiry into and an examination of the polis and so was Aristotle's Politics. The focus of Greek political thought allows us to assume that political science and political thought started with a concern with the State. In medieval times, Bluntschli echoed this when he declared that ‘Political Science in the proper sense is the science which is concerned with the State.’1

In the similar way, some recent commentators and writers like D. D. Raphael (Problems of Political Philosophy, 1970), N. P. Barry (An Introduction to Modern Political Theory, 1981) and others have stated that ‘political’ is generally related to the State and history of political theory has been mainly concerned with the state.2

Perspectives and theories regarding the origin, nature, sphere, role, functions and ends of the State are diverse and mostly partisan—diverse because of their approach and partisan because of their focus. Diversity of approach arises from how the State is viewed in terms of its:

- Origin: Whether the State is a product of force (Force theory); historical and social evolution (Sociological theory); divine dispensation (Divine theory); social contract; private property and class division (Marxian theory), etc.

- Nature: Whether the State is an organism/real personality (Organic theory); ethical or teleological institution (Idealist theory); legal or corporate personality (Legal/Juristic theory); artificial and utilitarian machine and coordinator and referee (Social Contract theory/Utilitarian theory); class instrument (Marxian theory); an agency/association like various other associations in society (pluralist theory), etc.

- Sphere of action: Whether the State should encompass limited aspects of life of the people and interfere sparingly (minimalist approach) or whether it should cover entire aspects of people's life (maximalist approach).

- Roles, functions and ends: Whether the State has its objective as ensuring achievement of moral self-realization by individuals or maintenance of natural rights and fulfilling the terms of social contract only or role in economic growth, equity and redistribution and welfare or being a means of class exploitation, etc.

We may begin by looking at the classification of various perspectives and theories attempted by some commentators and writers like C. L. Wayper, J. W. Garner, Andrew Vincent and Andrew Heywood (See Table 3.1).

Table 3.1 Classification of Various Perspectives and Theories on the State

| Commentator/Writer | Perspectives/Theories |

|---|---|

| C. L. Wayper

(Political Thought)3 |

|

| J. W. Garner

(Political Science and Government)4 |

|

| Andrew Vincent

(Theories of the State)5 |

|

| Andrew Heywood

(Politics)6 |

How the State has been understood:

How Nature of State Power is seen:

How the role of the State is viewed:

|

The functions and roles of the State can be studied in terms of the Idealist, Liberal, Neo-Liberal, Marxist, Neo-Marxist, Communitarian, Gandhian and other approaches. Further, it can be also studied in terms of social and developmental strategies such as private sector economy, public sector economy or mixed economy and stages of economic development vis-à-vis the First World, the Second World and the Third World. This, in turn, may also inform classifications like capitalist states, communist states, welfare states, post-colonial states, social-democratic states, etc.

Various perspectives and theories have evolved to understand the State in terms of its origin, nature of state power, role and the functions, and ends it serves. To organize our discussions on these, we propose to group these perspectives and theories as shown in Table 3.2.

Table 3.2 Grouping of Perspectives and Theories

How did the State Originate?

Political thinkers and analysts have differed about the factors and circumstances that are responsible for the origin of the State. Some attribute it to force, some to a divine dispensation and some to historical and social factors, including social contract by the people living in the state of nature or origin of classes and ownership of property, etc. We can discuss the various approaches briefly.

Force Theory of the Origin of the State

Voltaire's remark that ‘The first King was a fortunate warrior’ exemplifies the notion that a superior force must be behind the origin of the State. Force theory typically implies that the origin of the State is found in the subjugation of the weak by the stronger. In the primitive stage of evolution, physically stronger people must have prevailed over the weak and politically unorganized people, thereby establishing authority as rulers and commanders. This is also true in the case of stronger tribes and clans in relationship to the weaker tribes and clans. Physical force of a person or a tribe or a clan must have established domination over the weaker ones in the process of war and conquest. This might have resulted in the institution of kingship, which continued as a hereditary institution.

Two of the main proponents of the Force theory are Edward Jenks and Franz Oppenheimer. Edward Jenks in his book, A History of Politics (1900), supported the Force theory of origin of the State. He cited the example of emergence of state power in several countries of Europe to prove that the State has been based on force.7 The growth of kingdoms in many Scandinavian countries such as Norway, Sweden, etc. initiated by tribal overlords; conquests of Russia by the ethnic groups such as the Normans in the ninth century AD and the founding of kingdom of Normandy in the tenth century AD may be cited as examples in support of the Force theory. Jenks held that ‘there is not the slightest difficulty in proving that all political communities of the modern type owe their allegiance to successful warfare.’8 Franz Oppenheimer in his book, The State, Its History and Development (1914), also advanced ‘a conquest theory of State origins …’9 and traced the origin of the State through various stages. The main features of this theory can be summarized as:

- State is a product of superior physical force of individual or clan or tribe

- It is the war that begets the State

- War, conquest and domination of a person or a tribe/clan over the others who were weak and unorganized resulted in the institution of kingship

- The relationship between a war chief and his followers in the early periods finds its parallel in the modern feature of military allegiance

- Territorial character of modern states owes its link to the coming together of different races, tribes and people under the domination of a single ruler

The Force theory, by its very focus on force as a single most factor of origin of the State, is partial and one-sided. It ignores other historical and evolutionary factors like kinship, religion, customs, etc. that contributed to the development of the state. Some writers even doubt whether conquest could be a reason for origin of the state. Lowell Field remarks that ‘it may be accepted as a rule that the larger states of the ancient and medieval periods became larger through conquest. Whether in all cases the tiny nuclei of State organization—the city-states—began in the same manner cannot be proved.’10

Even if force can be reckoned as one of the factors in the origin of the state, the same may not qualify for its continuance. Force, domination and coercion alone cannot provide the basis for sustaining the State, it requires willing acceptance of the power of the State by the people. As Thomas Hill Green would say, ‘will’ not force is the basis of the state. Jean Jacques Rousseau says, ‘force is a physical power … To yield to force is an act of necessity not of will—at the most an act of prudence.’11 R. M. MacIver also finds fault with the argument that force alone can bring a group together to form the state.

However, in modern times, many writers and theorists have used force as an element of the State to extend their own arguments. Anarchists, for example, treat the State as a repository of force, which impedes self-realization of individuals and hence an ‘unnecessary evil’. Marxists feel that the State represents domination and exploitation of one class by the other due to economic power. Individualists treat the State, as ‘necessary evil’, which though can perform useful role, is against individual liberty.

The role of force, coercion and violence in establishing and sustaining colonial rule in Asia and Africa by various European powers (particularly Britain and France) give some degree of credibility to the force theory. Mahatma Gandhi's view that the State was a repository of force, coercion and violence was shaped during his stay in South Africa and the British rule in India. Even in contemporary times, we find various manifestations of state power like police and military force. Force remains one of the important elements in present-day state power as well.

Theory of the Divine Origin of the State

The theory of divine origin, considered one of the oldest theories of the origin of authority, covers two related arguments. One relates to the theory of divine origin of kingship as the sole authority of the State in general and the other relates to the theory of divine rights of the kings as a justification of royal absolutism in medieval Europe. The latter witnessed its full-blown operation in the Church versus the State controversy.

According to the theory of divine origin, political power and the State are extensions of divine power and its arrangements. The State has been instituted by the will of God and the king is the agent of that will. All powers and actions of the kings and rulers are supposed to be in the name of God and drawn from God's authority. It is not uncommon, as Gettell has pointed out, that in early Oriental empires rulers claimed a divine right to control the affairs of their subjects. G. Lowell Field, alluding to some of the earliest states in the form of ancient military monarchies, such as Egypt, Babylonia, Assyria, and Persia, mentions that ‘the ruler tended to assume the character of a high priest and even usually of living divinity’.12 This means that the kingly (political) and the priestly (religious/ecclesiastical) powers were neither separated nor differentiated.

We find mention of divine sanction in favour of rulers in the literature of Judaism, Christianity, Hinduism and Islam. According to R. G. Gettell, ‘the Hebrews believed that their system was of divine origin, and that Jehovah took active part in the direction of their public affairs’.13 Early Church Fathers also supported this theory and the Bible in the Old Testament hints at the divine origin of the kingship and rulers. Robert Filmer in his Patriarcha (1680) gave a systematic treatment to this theory by arguing that all authority came from the establishment of patriarchal power in Adam. Thus, all kings become heir to Adam's authority, which has divine origin.

In Islam, the religious–spiritual and the political are not differentiated. In the Quranic vision, there is no dichotomy between the two.14 To begin with, the Muslim ummah or the Muslim community was a politically organized polity in the Medina city-state, which the Prophet led. The Prophet has been described as the vice-regent of Allah on earth. The polity in Islam, inseparable from the spiritual and religious, has a divine origin. This was continued in the form of Khalifah (caliphs), the successors of the Prophet. The divine origin of polity in Islam may be said to manifest in two forms—one as Caliphates, the central seat of Muslim power, which got discontinued after the First World War and the other as theocratic states, based on religious and Quranic injunctions, that still continue in many Muslim countries.

Mention of divine intervention in the origin of kingship is also found in Manu's Dharmashastra or Code of Law and the chapter, Shantiparvan in the Mahabharta. They maintain that when the world became anarchic and greed and selfishness dominated the people, God created the king for protection, peace and order.15 In his Arthasastra, Kautilaya presents the king as occupying the position of both Indra, the god who is dispenser of favour and Yama, the god who is dispenser of punishment. A combination of these two qualities in the king points towards divine rights. However, it seems, Kautilaya's formulation is less developed than that mentioned in Manu's Dharmashastra, where it has been asserted that ‘a king is an incarnation of the eight guardian deities of the world, the Moon, the Fire, the Sun, the Wind, Indra, the Lords of wealth and water (Kubera and Varuna), and Yama’.16 Thus, we find that the theory of divine origin of kingship and the State is present in religious traditions. However, the most relevant use of this theory was to support the royal absolutism in medieval Europe.

In England and France, emergence of the authority of monarchy was preceded by the claim of the Church to both ecclesiastical (religious) and temporal (secular or worldly) authorities during the medieval times. To counter the claim of the church in temporal and secular matters, the doctrine of divine origin of the rights of the kings argued that the power of the kings was derived from the same source from where came the power of the church. When Europe was engaged in the Church–State controversy, the question of political obligation of the people to the king or the monarch was a matter of debate. The very claim by the kings of divine rights raised various issues relating to political obligation of the subjects to the king. Three issues engaged the attention of those who advocated royal and monarchical absolutism (royalists) and those who advocated subject's right to resist the kings (anti-royalists):

- Are the subjects obliged to obey the kings if they command against the law of God or act against the Church?

- What could be the nature of obligation and scope of resistance when subjects following a different path of religion (Catholics, Protestants) than the ruler or the majority, face oppression or tyranny?17

- ‘Is heresy in a ruler a valid ground for civic disobedience?’18

France and England, during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, faced civil and sectarian wars. Protestants and Jesuits attacked the claims of the kings and monarchs and argued for the right of people to resist in such cases. While the divine right doctrine sought to establish legitimacy of the king's right to rule, the anti-royalist attacks gave credibility to bases for resistance against the king's claim to absolute obligation of the subjects.

These circumstances required the absolutist monarchy to invoke the theory of divine rights of the kings to justify their position. The important elements of this theory may be listed as:

- Kings are vicars/representatives of God on earth, hence their actions have divine sanction

- Subjects owe their rulers a duty of passive obedience

- Rebellion against the king is sacrilege, even in the name of religion and by implication, even if the ruler is a heretic

- Divine rights of kings lead to hereditary power and royal legitimacy, which is based on birth and God's choice

Initially, the doctrine of divine rights of kings found its expression against the Pope's refusal to recognize accession of Henry of Navarre as the King of France on the ground of his being Protestant. Henry had to convert to Catholicism.19 William Barclay, a Scotch Catholic, who had taken refuge in France, provided an elaborate statement of the theory in 1600.20 He argued that all political authority proceeded from God and it never came from the people. However, it was James I of England, who, in his The Law of Free Monarchies (1598), gave a fuller exposition of the theory of divine rights of the kings. James I argued that ‘the essence of free monarchy was that it should be power over all its subjects. He stated, ‘Kings are breathing images of God upon earth’ and ‘The state of monarchy is the supreme thing upon earth; for kings are not only God's lieutenants upon earth, and sit upon God's throne, but even by God himself they are called Gods.’21 These statements of James I seek to establish the divine claim of the monarch/king to rule and therefore, to be obeyed, respected and revered by the people and not to be resisted. Secondly, for his activities and actions, the monarch becomes answerable to God only. Thirdly, monarch/king became the divinely instituted lawgiver for his people. This way, legal supremacy is sought through divine dispensation. Further, James I also advocated an inalienable and natural right of the king to his heir and any dispossession of the rightful heir as unlawful. The English royal family employed this argument during the English Civil War to justify their power.

The doctrine of Divine Rights of kings is based on the old theory of divine origin of kingship. This doctrine is weak in its theoretical and intellectual base. In fact, to achieve the same goal that this doctrine sought, Jean Bodin, Hugo Grotius and Thomas Hobbes invoked completely different arguments of sovereignty, which discredited the doctrine of divine rights. However, in a period when religious and political affiliations of the people were pulled against each other, this doctrine enabled the people to remain loyal to the church and religion and at the same time fulfil political obligation to the king and monarchy as if they are serving their faith. Nevertheless, in the wake of emerging constitutional state and liberal values, the doctrine of divine rights of kings was thoroughly discredited.

Kautilaya's Arthasastra on Origin of the State

Kautilaya's Arthasastra primarily relates to political economy and statecraft. However, it also mentions how kingship or monarchy came into being. It hints at some type of conscious decision on the part of the people to institute Manu, the son of Vivasvat as the king. Kautilaya locates the origin of monarchy as a result of what he calls matsyanyaya. Matsyanyaya implies an anarchic situation characterized by ‘bigger fish swallowing the smaller fish’. To get out of the situation, people instituted king as the restorer and protector of peace. He further adds that people also agreed to pay certain amount of taxes to the king in return for security and order. Arthasastra mentions that:

When people were oppressed by the law of the fishes, they made Manu, the son of Vivasvat, the king. They fixed one-sixth part of the grain and one-tenth of their goods and money as his share. Kings who receive this share are able to ensure the well being (yogákshema) of their subjects.22

As such, Arthasastra not only hints at the king being instituted by the people, it also makes the king responsible for the welfare of the people in return for the share collected from them. Though Kautilaya's formulation may not amount to some type of contract, as we understand following the tradition of Hobbes and Rousseau, it does hint at authority of the kings flowing from the people. Alternatively, it can be said that Kautilaya may have formulated this position to dissuade people for entertaining feelings of disaffection towards the ruler. This would legitimize the monarch's position and authority to collect taxes as share from the produce and possession of the subjects. In return, it promises welfare of the people.

Liberal Theories of Origin of the State

The Force theory and the divine origin theory both attribute the origin of the State to one of the factors—force or divine dispensation. They are as such mono-causal theories of origin of the State. While one highlights the domination–submission aspect of human relationship, the other bases itself on religious justification. These theories fail to give any comprehensive picture of the origin of the State and are highly speculative.

The social contract theory and the historical–evolutionary theory marshal sociological, anthropological, economic, psychological, political and scientific factors to attribute for the origin of the State. The social contract theory puts forward the concept of contract made by people living in the state of nature as the basis for the origin of the State. As such, it attributes the origin of the State to the collective choice of the individual persons. The historical–evolutionary theory identifies multiple factors as the basis for the origin o the State and attributes it to an evolutionary process. We may classify them as liberal theories of the origin of the State.

Social Contract Theory

Social contract refers to some type of covenant or collective understanding amongst the people in general. It is differentiated from any written legal contract. The Social Contract theory attributes the idea of authority to contract between the people. Though earlier, Cicero, Althusius and Grotius had hinted at social contract as the basis of authority, it came to dominate the political thought of the eighteenth century and found its expression in the writings of Thomas Hobbes, John Locke and Jean Jacques Rousseau. Commonly referred to as social contractualists, the social contract theory is attributed to these three thinkers. They explained that the origin of State was due to contract or agreement or covenant amongst the people living in the state of nature, though they attributed different reasons for the contract. To explain this, they probed: (i) the nature and psychology of human beings, (ii) the condition in the state of nature, (iii) the nature and terms of the social contract, and (iv) the nature or type of state/authority/sovereign power after the contract. Though the three thinkers adopt different explanations for all the above, we may proceed by giving a general statement of the social contract theory:

- The State emerged as a result of covenant or contract amongst the people living in the state of nature.

- The state of nature is considered pre-social as it is characterized by injustice, power play, absence of order, regulation and peace (Hobbes)/pre-political as it is characterized by absence of established authority (Locke) and pre-civil as it is characterized by the absence of true liberty (Rousseau).

- This condition of state of nature is attributable either to the egoistic and selfish nature of man (Hobbes), or to ambiguity in authority to legislate, execute and judge (Locke) or to absence of General Will (Rousseau).

- To secure and lead a peaceful life (Hobbes) or to enjoy certain rights where legislator, executor and judge are different authorities (Locke) or to gain civil liberty by losing merely natural liberty of doing whatever one's desires (Rousseau) lead people to make agreement or covenant or contract and institute authority.

- This contract brings into existence a sovereign authority to which all natural rights are surrendered (Hobbes) or a limited government with people retaining certain natural rights like right to life, liberty and estate (Locke) or General Will as the sovereign authority to which the particular will of individual is surrendered. In short, contract results in institution of authority/sovereignty/state.

- This theory assumes two forms—as theory of the origin of the State and as theory of relation between the governed and those who govern.23

- This theory is within the liberal framework and treats the State as an artificial product, a result of contract.

- Various political principles and concepts such as ‘sovereignty’, ‘unified authority’, ‘stability in the political order’ (Hobbes); ‘representation’, ‘majority rule’, ‘consent as basis of legitimacy’, ‘constitutional or limited government’, ‘individual rights’, ‘right to resist’, (Locke); ‘direct democracy’, ‘consensus/public opinion/general will’, etc., can be attributed to the formulations of the social contractualists.

We may discuss the formulations of the three social contractualists under the four aspects: (i) the nature and psychology of human beings, (ii) the condition in the state of nature, (iii) the social contract, and (iv) the nature or type of state/authority/sovereign power after the contract, differently.

Human nature and psychology of man

The difference in the approach of the three social contractualist thinkers starts with the difference in their understanding of human nature and psychology. Hobbes in Leviathan gave primacy to the instinct of self-preservation as the principle behind all human behaviour. Starting from the assumption that two types of feelings, desire and aversion are the moving factors in human beings, Hobbes stated that ‘what man desires he calls Good … and what he dislikes he calls Evil …’24 According to him then, what is Good is pleasurable and what is Evil is painful. If ‘self-preservation is continuance of individual biological existence, good is what serves this end and evil what has the opposite effect.’25 For Hobbes, it is true of human psychology that ‘the living body is instinctively set to preserve’ and as such man desires to preserve life.

Through his principle of self-preservation as the basic human psychology, Hobbes sought to establish that ‘desire for security’ is the fundamental need of human nature. Along with this principle of desire for security, there is an inseparable ‘desire for power’. As in the state of nature no one is sure of security and benefit of what one has or what one possesses, all seek continual power to secure what one possesses. Hobbes declares, ‘I put for a general inclination of all mankind, a perpetual and restless desire of power after power, that ceaseth only in death … because he cannot assure the power and means to live well, which he hath present, without the acquisition of more.’26 This continued desire for power leads to competition and perpetual ‘war of every man against every man’. As a result, man becomes a selfish, egoistic, and alienated individual, at war with others.

Locke in his Essays on Human Understanding explains the nature of man. For Locke, ‘desire is a feeling of uneasiness identified with pain, a feeling of which men want to get rid themselves.27 Thus, the objective of all human action is to substitute pleasure for pain. However, unlike in Hobbes, to achieve the objective, man does not stoop to selfishness, competition and war. On the contrary, for Locke man in state of nature is ‘sociable, altruistic and peaceful’. This is possible because human beings, for Locke, are rational and can discern and follow the law of nature. Since ‘rational people must concede that every human being has a right to life’,28 the state of nature is peaceful and social.

Rousseau's view on human nature emerges from his image of man as a ‘noble savage’. In his Discourses on the Origin and Foundation of Inequality, Rousseau seems to suggest that man's innate and uncorrupted conscience prevailed in the state of nature. Rousseau's view of idyllic and romantic primitivism in the state of nature and noble savagery of man prompts him to declare that ‘a thinking man is a depraved animal’.29 In this statement, we find Rousseau's rejection of primacy of reason, knowledge, progress of science and intelligence. Rousseau appealed to conscience, piety, sympathy and noble sentiments of man as the basis of progress and self-development of man and society. To him, two original instincts—'self-love or the instinct of self-preservation and sympathy or the gregarious instinct’ make up man's nature.30 These instincts are beneficial for man as an individual and also as a group.

However, Rousseau needs to resolve the dilemma of self-love (love for oneself) coming in clash with sympathy (love or affection for others) as instincts in man when man seeks to satisfy both. To resolve this, a guiding principle grounded very much in the nature and sentiment of man is required. Rousseau finds this guiding principle in the form of ‘conscience’. Conscience is a sentiment, which is natural to man and prior to reason. Conscience makes man do right for himself as well as for others. But this being an instinctive expression, cannot itself tell what is right. It then, further requires another guiding principle that tells what is right. Reason, which helps man know what is right, guides him to do what is right. Thus, for Rousseau, conscience and reason in a man working closely harmonize self-love and sympathy and give rise to a society where man finds the fullest expression of his self.

In all the three social contractualists, we find a common understanding of human nature insofar as they relate to liking for pleasure or self-love and fear against harm to oneself. While for Hobbes, this fear leads to a situation of anarchy in the state of nature, for Locke and Rousseau, this fear is moderated by the sociable and sympathetic instinct in man. Hobbes blames the human nature for ills in the state of nature, for Locke it is absence of external regulation and for Rousseau, it is individual's too much emphasis on a particular will. Their understanding of human nature shapes the views of Hobbes, Locke and Rousseau on the condition in a state of nature and the terms of the social contract.

Condition in the state of nature

‘State of nature’ signifies a condition of human existence from which man seeks to emerge either due to an anarchic condition or an absence of authority or regulation on the activities of individuals or lack of condition of self-expression. In short, it is a stateless condition without a superior authority (either a Leviathan or a Commonwealth or General Will) to regulate and provide the condition of life (Hobbes's self-preservation), natural rights (Locke's life, liberty and property) and liberty (Rousseau's civil liberty). Since this condition of human existence is inadequate, unsatisfactory and undesirable, it requires escape to a better condition and hence, a social contract to set this up.

Hobbes deplores life in the state of nature as ‘solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short’. This condition is attributable to what Hobbes identifies in human nature as competitive, selfish, seeking power continually, diffidence, vainglory and egoist. Due to this, no one is sure of the fruit of their labour and industry. And to keep what one has in possession, he has to secure more power, a continued search for power. In the state of nature, each individual lives in fear of the other. Each one is being more or less equal in power to the other; strength of one offset by ingenuity of the other. This makes them diffident. In the state of nature, there are limited rights available to man and that to what one can secure through physical power. In fact, there being no principle of right or wrong, justice or injustice, honesty or deceit, the cardinal rule in the state of nature is ‘he should take who has the power, and he should keep who can’.31 This anarchic situation is a product of what Hobbes identifies as instinct of self-preservation in the state of nature. To this extent, right to life is an important element but this ‘modest need for security’ becomes equivalent to an endless need for power—’war of every man against everyman’.

Now, if this is the Hobbes's pre-social and pre-civil state of nature, is it worth staying on in such a situation? If not, then what can make men get out of this situation? Man has ‘desire’ which makes him seek what others also want, leading to a war-like situation. However, along with desire, Hobbes adds another principle of human nature—reason. But what role does reason play? Reason adds foresight and regulative power in human nature, which help men realize the importance of effective self-preservation. For Hobbes, reason only can guide men away from a ‘hasty acquisitiveness’ (search for power which prevails in the state of nature) to a more ‘calculating selfishness’ (regulated and adjusted self-interest which is found in society).32 The desire for effective security and self-preservation has to reject the state of nature and be more regulated. This could be possible only when men recognize, through foresight, the value of certain laws. These certain laws which reason teaches men to obey are ‘Natural Laws’. Hobbes's Natural Laws are merely ‘counsels of prudence’ and not embodiment of morality or justice.33 These are counsels of prudence because they teach men not to endanger the security of others, as one reasonable being would not expect the same for oneself. In Hobbes's words, law of nature ‘is the dictate of right reason … is a precept, or general rule, found out by reason, by which a man is forbidden to do, that, which is destructive of his life … ,’34 In short, in consonance with the basic principle of self-preservation and security, reason guides men to follow natural laws. This in turn, teaches that peace and cooperation is desirable for more effective self-preservation and security.

Hobbes identifies nineteen Natural Laws or Articles of Peace that ‘concern the doctrine of civil society’.35 The most important of them, which will help men come out of the state of nature are: (i) every man should seek peace, (ii) surrender equal rights to possess all things and be contented with as much liberty against other men, as he would allow other men against himself, (iii) peace requires mutual confidence and trust and each should keep the covenants/engagements that they make to do this. This for Hobbes becomes the basis for social contract for constituting civil society and instituting the sovereign.

Locke's understanding of human nature as peaceful, altruistic and sociable shapes his views on conditions that prevail in the state of nature. Locke's picture of the state of nature accordingly contrasts with the one painted by Hobbes. Instead of being ‘solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short’ as Hobbes says, for Locke, the state of nature is ‘a State of Peace, Good Will, Mutual Assistance and Preservation’. Locke's state of nature is not pre-social; it is only pre-political, as there is absence of regulating authority and not freedom or equality. Locke's state of nature is a condition of ‘perfect freedom as well as of perfect equality …’36 Men are equal and free to act as they think fit but within the bounds of the law of nature. Thus, equality and liberty to act does not mean it is a state of licence. The presence of the law of nature provides both rights and duties. Locke's state of nature is neither licentious nor lawless, as Locke says:

State of nature is a State of Liberty, yet it is not a State of Licence … Because … The State of Nature has a Law of Nature to govern it, which obliges every one, and Reason, which is that Law, teaches all mankind, who will but consult it, that being all equal and independent, no one ought to harm another in his Life, Health, Liberty, or Possessions.37

This way, Locke provides two aspects of the state of nature—natural rights and acknowledged duties. Natural Law provides certain inalienable or inviolable natural rights—rights to life (life and health), liberty and property (possessions/estate). Right to life is right to self-preserve and secure one's existence, which is the only right Hobbes feels worth providing. However, Locke adds right to liberty, as right to do whatever one wants as far as it is not incompatible with the Law of Nature. Locke also adds right to estate or property or possession as ‘right to anything with which he has mixed labour, provided he makes good use of it, “since nothing was made by God for man to spoil or destroy”’.38 At the same time, Natural Law also enjoins certain acknowledged duties in the form of obligation not to hurt other's life, health, liberty and possessions (or life, liberty and estate). For Locke, man, being a rational creature, is capable of discovering moral truths and recognizing the law of nature. These duties command him to do what he can to preserve others when his own preservation is not at stake; he should keep his promises as keeping promises belong to men as men.

Now, if for Locke, state of nature has inalienable rights and acknowledged duties and is social, moral and peaceful in character, then why men should seek to get out of it and engage in social contract. The identification of reasons for this leads Locke to define the terms of the social contract and character of the political set-up where inalienable natural rights are carried over to lay the foundation of a liberal social and political order. Though for Locke, the state of nature is not a state of war, as Wayper says, ‘it is unfortunately a state in which peace is not secure’. This insecurity of peace arises from ‘corruption and viciousness of degenerated men. Though majority tends to follow the law of nature, a few men may act in self-interest. There being no regulating authority, each one tends it to interpret in his own favour. For Locke, despite all its equality and liberty, state of nature still leaves three important wants unsatisfied—‘the want of an “established, settled, known law”, the want of a “known and indifferent judge”, the want of an executive power to enforce just decisions’.39 In short, state of nature does not have a legislative authority, an executive authority and a judicial authority—the three organs that we identify as organs of a government. It is the requirement of a legislator, an executive and an arbitrator to make enjoyment of right to life, liberty and property meaningful that social contract comes into being.

Rousseau's state of nature has to reflect the quality man possesses as man. In his Discourses on the Origin and Foundation of Inequality, he treats man as ‘noble savage’, who along with self-interest also possesses a feeling of sympathy for others. The feeling of sympathy reflects ‘innate revulsion against suffering in others’, what is called pity. According to Rousseau, the ‘noble savage … tempers the ardor he has for his own well-being by an innate repugnance to see his fellow man suffer.’40 This belief of Rousseau in the innate goodness of man to have pity due to which man feels and shares the suffering of others, leads him to conclude that the state of nature is a state of peace. It is a state of idyllic happiness, romantic freedom and primitive simplicity.

However, this peaceful and romantic state is disturbed due to emergence of property, institutions and regulations and with it the concept of ‘mine’ and ‘thine’, leading to inequality. This might have destroyed natural liberty and put external law of inequality and property leading to a need for a civil society.

In The Social Contract, however, Rousseau takes a somewhat different view of the state of nature. Though this does not radically alter his understanding of man, however, it presents a different view. As per this formulation, in the state of nature, an individual enjoys natural liberty and is free to act. But this liberty is driven by instinct and self-love. Physical impulsion and appetite is the basis of action. Appetite driven liberty is what Rousseau calls ‘slavery’ to selfish desire. His remark that ‘obedience to the mere impulse of appetite is slavery’ exemplifies this aspect. In the state of nature what man has is actual will—an impulsive and unreflective will, which is based on self-interest and not well-being of the community. Real will, as consciousness of common good, though present is not fully realized. It is this search to locate liberty as an integral part of the community, which expresses itself in the form of General Will that leads Rousseau to find the reason for the social contract. Rousseau presents an ‘organic view’ of liberty, which is not licentious and unlike in the state of nature where actual will is dominant, liberty in civil society presents real liberty as it is a product of the General Will. By formulating that real liberty lies in following the law of the General Will and enjoying civil liberty, Rousseau put the state of nature as an undesirable state of affairs. Thus, a transition from state of ‘actual will’ to a state of ‘general will’ is necessitated for enjoying civil liberty.

Nature and terms of social contract

The three social contractualists viewed human nature and the prevailing condition in the state of nature somewhat differently. However, as Garner opines, ‘whatever the difference of opinion among the philosophers as to the actual character of the state of nature, they were all in accord that it was unsatisfactory condition of society.’41 The unsatisfactory condition for Hobbes is an anarchic situation and threat to life and security; for Locke, absence of appropriate authority to legislate, to execute and to arbitrate; and for Rousseau, it is dominance of self-love (‘actual will’) over consciousness of common good (‘real will’) that hinders men's self-realization. Though Hobbes, Locke and Rousseau identified different compulsions that force men to covenant and establish civil society, they nevertheless, agree that the State and its authority emerged as a result of voluntary social contract.

The social contract should reflect not only the transition from the state of nature to a civil society, it should also set such requirements that exclude any possibility of reversion to the state of nature again. To ensure this, Hobbes institutes the Leviathan, a full sovereign authority; Locke, a limited constitutional government; and Rousseau, the General Will. Hobbes's understanding of human nature in terms of primacy of self-preservation and his fear of a potential anarchic situation that could engulf Britain in the seventeenth century led him to postulate an all powerful sovereign—Leviathan. In fact, Hobbes's Leviathan is a metaphor for excluding any possibility of anarchy. Locke, on the other hand, supports limited/constitutional government that acts as a trust on behalf of society. This is to protect the inalienable rights of individuals. Rousseau gave primacy to community over individual. His understanding that self-realization of individual would be a part of the community led him to set up General Will as the sovereign.

For Hobbes, the social contract is a covenant between individuals by which everyone subjects themselves to a sovereign in the following manner:

I authorize and give up my right of governing myself, to this man, or to this assembly of men, on this condition, that thou give up thy right to him, and authorize all his actions in like manner …42

Hobbes called the receiver of this right ‘that great Leviathan’ or ‘that mortal God’ to which we owe our peace and defence. The following features and characteristics describe the nature and terms of the social contract formulated by Hobbes:

- To seek peace, every one gives up their right to govern themselves and to seek power continuously fearing others—this corresponds with the first law of nature.

- All authorize their natural rights to the receiver, the Leviathan or the sovereign, who is the recipient of power of men—this corresponds with the second law of nature.

- ‘This man or this assembly of men’ seems to envisage or justify a monarchic as well as aristocratic and democratic state—though Hobbes might have a monarchic state in mind.

- The Leviathan is not party to the contract and owes no obligations, though surrender of all powers and rights of men is complete except the right to life.

- Leviathan's authority is legitimate as each individual has consented so.

- It is a single contract that give rise to the Commonwealth (the state) and the Leviathan (the sovereign).

- Hobbes makes no distinction between society and the State and the State and government.

- By contracting, the multitude of individuals becomes a commonwealth, a state which is an artificial person distinct from the multitude—the State as something artificial, ‘a machine, an artefact, a contrivance of man.’43

- Unity of the sovereign represents the unity of the multitude—’the unity of the representer, not the unity of the represented that makes the person one.’44

- The sovereign becomes the repository of all strength and power of the multitude and represents ‘one will.’45

- This one will does not provide place for primacy to any associations including the church, as they are ‘worms in the entrails the body politic’—Hobbes proposes a unitary state not pluralist state.

- Remove the sovereign, the unity goes and so does the commonwealth—state of nature again, which is undesirable and hence the sovereign is absolute and directs the actions of men to common benefit—security and life.

- To do this, the sovereign needs power to keep peace and apply sanctions to curb men's innate unsocial inclinations as ‘covenants without sword are but words’ and ‘the bonds of words are too weak to bridle men's ambition, avarice, anger, and other passions, without the fear of some coercive power.’46

- Leviathan or the sovereign is the sole source of all laws (all laws are command of the Leviathan), rights, justice and possess absolute power—monist concept of sovereignty.

- Neither the law of nature, nor law of God nor conscience can be pleaded against the Leviathan as law is the command of the sovereign and represents public conscience. He is the sole interpreter of law of nature or the law of God.

- Leviathan, thus, is absolute, inalienable, indivisible, irrevocable and permanent.

If such is the nature and terms of contract, Hobbes seems to have removed any fetter to an absolute sovereignty. And by doing so, he even removed what Bodin puts as limitations of the sovereign. However, since the very origin of the social contract and Leviathan is grounded in security and right to life of the individual, Hobbes puts this as the only limitation on the Leviathan. Leviathan cannot will or command a man to kill himself, as it obligated to protect the right to life of the individual. It is the violation of right to life alone that men are empowered to revolt against the Leviathan.

In the backdrop of the Glorious Revolution of 1688, while Hobbes gave enough theoretical backing to absolute monarchy and the rule of Stuart kings, it was left to Locke to take up the same subject and reach to a different conclusion. True to his contemporary backdrop, Locke advocated constitutional monarchy and limited government in his Two Treatises on Civil Government. Locke's formulation of inalienable natural rights and absence of appropriate authority to legislate, execute and adjudicate in the state of nature are the two aspects that determine nature and terms of social contract. For Locke, social contract as a means to transit from the state of nature to civil society means:

Whosoever therefore out of a state of Nature unite into a community must be understood to give up all the power necessary to the ends for which they unite into Society … And this is done by barely agreeing to unite into one Political Society, which is all the compact that is, or needs be, between the Individuals that enter into or make up a commonwealth. And thus that which begins and actually constitutes any Political Society is nothing but the consent of any number of Freemen capable of a majority to unite and incorporate into such a society. And this is that, and that only, which did or could give beginning to any lawful Government in the world.47

The following features and characteristics describe the nature and terms of the social contract formulated by Locke:

- Social contract of all with all to constitute a commonwealth or ‘political society’ (a community) at first and then to institute the government as agent or trust of this commonwealth as ‘a fiduciary power to act for certain end’—some say Locke's formulation implied two social contracts, one to constitute political society and the second to institute government.

- The social contract is by the consent of all and unanimous. But this political society is capable of majority, i.e., decisions to be taken by the political society now would be by majority and need not be unanimous.

- Once consented, the contract is irrevocable and each generation must consent to it.

- Social contract results in partial surrender of rights whereby all surrender their rights to be a single power of punishing and be the interpreter of natural law and its executor as well as adjudicator.

- Inalienable rights of life, liberty and estate is retained by the individual in political society also.

- Even partial surrender of rights, then, is to the political society which retains ‘supreme power’ and as such people organized as political society are sovereign.

- This sovereign subsequently institutes government as a trust to perform the functions that ensure the end for which the contract has been entered into—to have a legislator on behalf of all, and executor and an impartial adjudicator.

- The primary end of government is to secure and protect the inalienable rights of life, liberty and estate.

- The political society is both creator and beneficiary of the trust/government.

- To the extent the government breaks the trust of protecting these inalienable rights, it forfeits the trust of the people and the latter can revolt against it—Locke sought to defend the right of revolution in context of Glorious Revolution of 1688—this is Locke's justification of revolution without incurring instability.

- Revolt against government, however, does not constitute dissolution of political society and is only change in government.

While Hobbes transferred all rights of the individual, except the right to life, to the great Leviathan, Locke allowed rights to life, liberty and estate as indefeasible rights to be retained by the individual. While sovereignty of the Leviathan is supreme, it is much curtailed and trimmed in Locke's state. From Hobbes to Locke, the concept of sovereignty or supreme authority travelled from absolutism to a limited government.

Notwithstanding Rousseau's views contained in his Discourses on Inequality on the emergence of state, our focus here will mainly be on his formulation contained in his The Social Contract. The thematic concern of Rousseau's thought revolved round the inquiry to:

Find a form of association which will defend and protect with the whole common force the person and the property of each associate, and by which every person, while uniting himself with all, shall obey only himself and remain as free as before.48

This form of society is possible only when an organic unity is achieved with every individual having consciousness of the common good. This is exactly what General Will represents. In the state of nature, individual gives primacy to actual will (sense of self-love), though real will (consciousness of common good) is also present. For Rousseau, this impulsive and unreflective self-interest is an undesirable state of affairs, if man has to realize ‘moral liberty’, liberty with consciousness of common good. To enjoy moral liberty and not merely instinctive liberty, social contract is required and this is how the liberty of the individual and necessity of social order must converge. This requires transiting from the state of nature to civil society. For Rousseau social contract comes into being when:

… each of us puts his person and all his power (faculties) in common (stock) under the supreme direction of the general will, and, in our corporate capacity, we receive each member as an indivisible part of the whole.49

The following features and characteristics describe the nature and terms of the social contract formulated by Rousseau:

- It's a single contract of all with all to let their ‘real will’ (individual sense of common good) prevail and constitute a volonte generate, the general will (common consciousness of the common good).

- The General Will, which is the common consciousness of the common good, represents the organic unity of the people who constitute a civil society or a body politic.

- It is ‘a common Me’—Un Moi commune, my real will writ large and in association with the similar real will of others writ large includes me as well as others.

- This civil society now acts as a corporate unity and is repository of all powers which an individual had in the state of nature and in addition also has civil liberty which it creates.

- This way, ‘each man giving himself to all, gives himself to none’ and by ‘what he loses by the social contract is his natural liberty and unlimited right to do anything that tempts him which he can obtain … what he gains is civil liberty and the ownership of all that he possesses’.50

- By virtue of this, it is sovereign and source of all rights and justice, liberty and freedom—individual liberty is neither beyond nor above what General Will prescribes—’one can be forced to be free’ as General Will only know what freedom is.

- Sovereignty remains with the general will and cannot be represented—it is popular sovereignty that characterizes Rousseau's civil society.

- General Will is indivisible, absolute, inalienable, permanent and all comprehensive.

- Sovereign is not concerned with details of the government. People entrust executive powers to the government as an agent. As long as the General Will is sovereign, form of government—monarchy, aristocracy or democracy does not matter.51 However, generally, direct democracy is associated with Rousseau's idea of General Will.

For Rousseau, social contracting involves ‘the total alienation of each associate and all his rights’52 and a complete surrender of an individual to a corporate body. For Hobbes, this corporate body is the Leviathan, standing external to the people in one man or assembly of men. For Rousseau, it is the Volonte Generate, residing within the people impersonally. It seems, Rousseau's general will is Hobbes's Leviathan with its head chopped off (impersonal). Locke, one the other hand, does not require complete submission of individual to the Commonwealth. The commonwealth is supreme in certain ways and the individual retains inalienable natural rights. This sounds like the community having partial sovereignty amidst individual retaining natural rights outside the sovereignty of the community. What does this difference mean for the type of the State and government in a post-social contract society?

Nature and type of state in the civil/political society

Since the State is a result of contract, it is an artificial construct. So is the post-contract civil society, except for Rousseau. As such, one of the challenges is to achieve unity and stability in the civil society. Hobbes sought to achieve this by assigning unity to the Leviathan, the sovereign; Locke did that by retaining most of the rights with the individuals and letting the State interfere minimally. For Rousseau, the General Will itself is an organic unity.

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Europe was undergoing various revolutionary changes—political, economic and social. Political, to chart a direction from royal absolutism to constitutional democracy; economic, in the form of industrial and capitalist production; and social, as a result of rise of the bourgeois and middle classes and decline of the aristocratic and feudal structure. The three social contractualists were responding to the upheavals and drama that was integral to these changes. While Hobbes was sympathetic and in fact supportive of royal absolutism, Locke was convinced that a limited constitutional state was the only suitable political expression in times of rising bourgeois class (the class of rising entrepreneurs/capitalists) in England. Rousseau's views influenced the French Revolution and found its expression as the ‘will’ of the people at the centre stage of political arena.

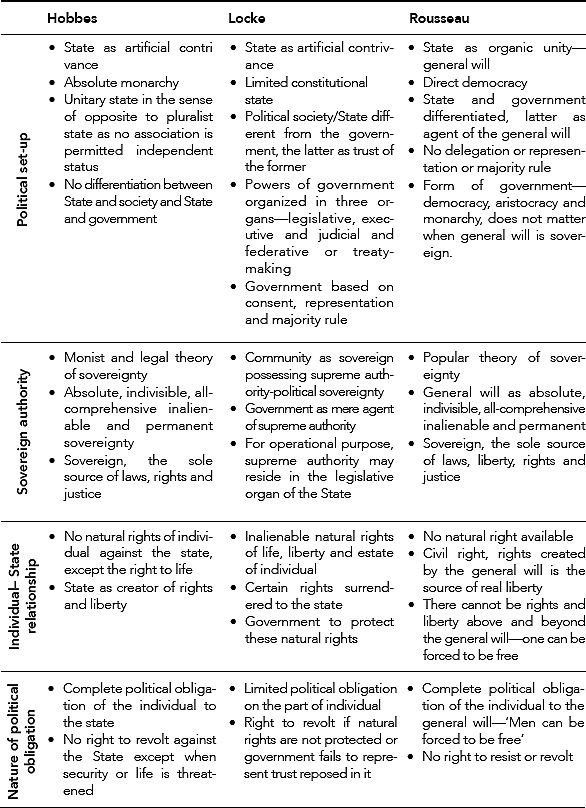

The type of political set-up, nature of sovereign authority in the state, relationship of the individual with this authority and the nature of political obligations that the individual and the State bear towards each other reflect the vision of the contractualists. We may put these briefly as shown in Table 3.3.

Critical Evaluation of the Social Contract Theory

Social contract theory may be termed as the most influential political doctrine that came up in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and that could boast of a long line of supporters and sympathizers. Besides Hobbes, Locke and Rousseau, various philosophers, jurists, political writers, poets, and religionists supported the social contract theory. These included ‘Hooker, Milton, Grotius, Pufendorf, Wolff, Suarez, Kant, Blackstone, Spinoza, Fichte, and many others’53

However, equally impressive is the list of those who criticized and attacked the theory. Amongst them, we may count David Hume, Jeremy Bentham, Edmund Burke, Austin, Lieber, Henry Maine, Thomas Hill Green, Bluntschli, Pollock and others. Further, as Andrew Vincent maintains, ‘the development of the historical school of law, legal positivism and sociological theories uniformly rejected contractual ideas.’54 A critical evaluation of the social contract theory finds faults with its historical and sociological possibility, philosophical tenability and legal soundness. We may see the grounds that challenge the social contract theory.

Historical and sociological possibility

The critics invariably doubt the historical possibility of such a social contract. It is said that historical and sociological evidences do not support validity of the state of nature. By challenging the very basic assumption of the theory about the existence of the state of nature, the critics push the social contract theory in the realm of speculative theory. As the advocates of the Historical–Evolutionary theory of origin and development of the State suggests, it may not be feasible to divide evolution of social and political organizations into pre-and post-social. Men are incapable of living otherwise than in society. It can be argued that human beings, due to their associative and social nature, cannot be said to have existed in the state of nature, as mere individuals competing (Hobbes), deciding on their own (Locke) and wandering aimlessly (Rousseau). A more logical position could be to see the State as a continuous and gradual evolution, instead of a one-time transition as a result of the social contract.

Henry Maine, who supports the Historical-Evolutionary theory, pronounced the social contract theory as ‘worthless’. Some of the instances that are cited as providing historical proof of a covenant are The Mayflower Compact (1620) and The Constitution of Massachusetts (1780). However, upon examination these are found to be by those men who were already conscious of political authority and the concept of the State and should not be taken as an example of founding a new commonwealth.55 The Mayflower episode relates to the visit of 101 British emigrants in the ship Mayflower to America who ‘reached Cape Cod, in what was to be Massachusetts, in 1620.’56

However, before landing, they ‘entered into an agreement whereby they “solemnly and mutually, in the presence of God and of one another, covenanted and combined themselves together into a civil body politic for better ordering and preservation”…’ Similarly, the constitution of Massachusetts (1780) ‘which asserted, “that the people have entered into an original, explicit, and solemn compact with each other” is sometimes cited as furnishing historical proof’.57 These examples hardly provide any indication of the social contract that Hobbes, Locke and Rousseau talked about, as these men were already familiar with the institution of government. Garner says, ‘the transaction was nothing more than the extension of an already existing state to a country not yet inhabited by civilized races. The Mayflower covenants, in fact, expressly acknowledged that they were “loyal subjects” of an existing sovereign’. Thus, historically, the social contract remains in speculative realm.

Sociological, anthropological and historical researches by Morgan, Maine and others suggest a multi-factor possibility of emergence of the State and political institutions. In fact, Maine has maintained that evolution has been from status to contract, the latter being a very late development. As such, the idea of contract cannot be treated as having existed from the beginning itself.

Philosophical tenability

The critics hold the social contract theory as philosophically untenable. The reason being, it: (i) treats State and society as a mechanical contrivance merely to fulfil selective needs; (ii) assumes a state of nature and also automatic endowment of political consciousness within it; (iii) assumes existence of rights and liberty independent of society and state. Firstly, the artificial contrivance view of the State espoused mainly by Hobbes and Locke is not acceptable to those who treat the State as something of a fulfilling and teleological nature.

Idealists and those who view the State and individual relation in terms of organic unity, treat the State as having a certain purpose—ultimate abode of man as a social being (Aristotle) or march of God on earth (Hegel) or self-realization of the individual. The State, instead of being a mere artificial and mechanical product, is the ultimate goal of man's associative instinct and ethical realization. Secondly, the social contract theory presupposes political consciousness in the minds of those who are staying in the state of nature. Political consciousness and rational faculty are part of men's social existence. Thirdly, many thinkers such as Green, Bentham and others criticized the theory and doubted the possibility of ‘natural rights’ and ‘liberty’ in the state of nature. Green, for example, criticized the concept of natural rights on the basis that rights are not exterior to man and do not emanate from something transcendental. He feels that rights emanate from the moral character of men. This character is the basis of moral freedom or a positive power of doing or enjoying something worth doing or enjoying. In short, for Green true liberty is liberty of self-realization. And to achieve this goal, men require rights. Thus, moral freedom postulates rights, and rights as such are recognized by the moral consciousness of the community as conditions of attainment of the moral end. Rights cannot exist unrecognized, hence concept of natural rights without the recognition of the society is untenable.

Bentham dismissed the theory as ‘rattle’ for amusement. The reason for this could be Bentham's view of legislative supremacy of the State and being ‘sole source of rights’. If the State is the sole source of rights, to accept that rights can be ‘natural’ and exist beyond the State is, what Bentham says ‘simple nonsense—natural and imprescriptible rights rhetorical nonsense—nonsense upon stilts’.58 For him, rights cannot be natural, they can only be recognized and prescribed by the state. For Edmund Burke, even if social contract is assumed to exist, it marked the end of natural rights rather than it continuance, as Locke would say.

Legal soundness

The social contract theory has been charged with lacking legal soundness. Tom Paine criticized it on the ground that it required an eternally binding contract on each generation. For Hobbes, Locke and Rousseau, it is an irrevocable contract and consent once given is binding not for only those consenting but for all the coming generations implicitly. Paine terms this as ‘dead weight on the wheels of progress’. Leon Duguit, a French jurist, rejects the theory as ‘unsustainable hypothesis’. Duguit feels that ‘since men who are not already living in society cannot have any notion of contractual relations and obligations’,59 the idea of the presence of contract in the minds of those in the state of nature is unsustainable. Henry Maine also concluded that contract, as a way of relationship amongst men is a later development than status. Furthermore, it may also be argued that contract implies a voluntary relation, contractual relation between parties. Conversely, one can also choose to stay out of it. As a contract, it should be restricted only to the original contracting parties and should not be binding on those who did not consent. Thus, in the face of legal meaning of the word, contract as voluntary relation and absence of expressed consent of subsequent generations—state becomes a ‘matter of caprice’. As Garner say, ‘if followed out to its logical conclusion, it would lead to the subversion of all authority and possibly the dissolution of the state’.60 As a result, the social contract theory appears anomalous as a theory of the origin of state. One more aspect that appears anomalous from the legal angle is the priority of contract over authority—social contract creates authority. Generally, as we understand today, there should be some sanction or authority behind a contract, i.e., a contract must derive from a source of authority standing independent and above the contracting parties.

Nevertheless, the terminology of legal contract, as it appears in modern parlance, may not be the appropriate way of appreciating the social contract theory. A more plausible way is to look at this in terms of the past as future. Given the contemporary social, political and economic conditions, the social contract theorists seem to extrapolate a condition of the state of nature (at least Hobbes and Locke) in the past. The state of nature is a picture as if a sound ground of political allegiance of the individual and the authority of the state is not defined. In fact, for Locke and Rousseau, the resulting state is a better guarantee for enjoyment of natural rights and civil rights, respectively. It seems, the social contract theory is less a theory of origin of the State and more a doctrine of nature of the state and relationship of the individual with the state. It redefines the principles of political obligations and deals with the crucial theme of political theory, i.e., resolving the state-individual anti-thesis; why should the individual obey the State and what rights of the individual should the State protect. In the social contract, the individual obeys its own creation and the State serves its creators. The following contributions of the social contract theory may be listed:

- It sought to establish that all authority is derived from the people and provided justification for resistance and revolt against tyranny of rulers. It discredited the divine rights of the kings.

- By bringing the individual at the centre stage of political thought, it was responding to the need of an emerging capitalist society and what Macpherson calls, ‘possessive individualism’.

- The social contract theory is within the framework of liberalism and has contributed to the principles of liberal democracy—the principles of consent, majority rule, representation, government as trust, limited government, separation of powers, collective will of the people (public opinion).

- State as an artificial construct and trust of the people is a conciliator of interests and a neutral arbiter.

- Principles of individualism, liberalism, democracy, sovereignty, political obligation and legitimacy owe to the social contract theory.

- Political commentators and philosophers such as Ernest Barker and John Rawls have sought to highlight the relevance of the contract theory in terms of constitutionalism and welfarism, respectively. Barker maintains that ‘constitutionalism is a modern substitute for contractu-alism’.61 Constitutionalism is used in the meaning of limitations on government through rights of the individual and separation of powers, which, in turn, provides doctrinal basis for liberal democracy. American philosopher, John Rawls has used the contract theory to build up his theory of distributive justice and welfare.

Notwithstanding, it remains a doubtful theory of the origin of the State and even fails to fully capture the nature of state power. For pluralists, it fails to account for the role of associations through which individual identity and relationships with the State are mediated. For Marxists, its identification of reason for origin of the State is misplaced, as it ignores the role of property. Further, it is a theory of bourgeois State and hides class differences under the cover of individualism. For the exponents of Historical-Evolutionary theory of the origin of the state, it is an incomplete theory of origin of the state, as it does not account for historical, sociological, economic and other relevant factors in the origin of the state.

Historical-Evolutionary Theory of Origin of the State

The Historical-Evolutionary theory does not appreciate that origin of the State is due to some social contract or force or divine dispensation alone. Rather, it adopts a multi-causal approach and attributes the origin of the State to a variety of causes. These relate not only to force, war and power and religion but also to other social-economic factors. It has been noted that ‘there is no reason to regard the State historically as a universal feature of social organization’ and this has validity due to the fact that ‘many relatively primitive peoples lacked either a distinctly territorial basis of organization or any permanent institutions of command, coercion, or punishment’.62 This is to suggest that a journey from statelessness to complex state organization must have been achieved through a variety of factors. A general statement of the Evolutionary-Historical theory may be given as follows:

- It treats the origin and development of the State neither as a result of divine dispensation nor of force, nor of contract but of a variety of factors, a multi-causal approach.

- It deals with forces and factors that worked in primitive conditions of human life and helped evolution of institution of the state. It seeks to map various factors that are responsible for further development and transition of the State from one stage to another—primitive to the modern stage.

- This approach is based on anthropological, sociological, historical and economic evidences.

- As the State is treated as a product of society or social factors, State and society are differentiated.

Contributions to the theory

Lewis H. Morgan, Friedrich Engels, Sir Henry J. Sumner Maine, J. F. McLennan, Edward Jenks, R. M. MacIver are some of the jurists, historians, ethnographers and sociologists who have studied and commented on various aspects of primitive social relationships, authority and evolution of the state. While Morgan, Maine, and Jenks have analysed the way authority, marriage, descent and kinship, etc., are organized amongst the primitive people and forces that worked in evolution of the state, Morgan, Engels, Maine, Bagehot and MacIver seek to show not only the evolution of the State but also its historical development. Engels offers a Marxian perspective and builds up his thesis of class nature of power and social relations drawing from Morgan's researches.

Lewis Morgan in his Systems of Consanguinity and Affinity of the Human Family (1871) and Ancient Society (1877) analysed the system of kinship, i.e., the way descent and lineage is sought, e.g. male line or female line and the basis of social organization.63 In these two books, he presented that a system of kinship prevailed among various aboriginal people. Taking the systems of kingship as the starting point, he reconstructed the forms of family corresponding to them. He stated that tribes were endogamous. Groups within tribes who were related by blood on the mother's side (gentes, which signify kinship or descent within which marriage was strictly prohibited) were exogamous. This was based on system of consanguinity, kinship based on blood relationship and not relationships based on marriage. He further concluded that gentes organized according to the mother's right were the original form, out of which, gentes based on the father's right originated. This, in one way, shows that matriarchy was the earliest form of social organization. Engels analysis of Morgan's work on Iroquois (American Indian Tribes) suggests that these gentes being part of tribes, elected a tribal chief and tribes had their confederacy. However, they represented a form of society ‘which as yet knows no state’.64 According to Engels, in the social evolution, the state developed much later when patriarchy gave way to inheritance of property by children and then hereditary nobility and finally to some form of public power.

J. F. McLennan in his Studies in Ancient History (1886), traced descent through mothers and kinship through the female line. He also suggested that initially, polyandry prevailed. He found examples of two types of marriages—marriage within the tribe (endogamous) and marriage outside the tribe (exogamous). He maintains that exogamy was due to scarcity of females within the tribe. This led to forcible acquisition/abduction of women from other tribes. Scarcity necessitated exogamy and also common possession. Thus, McLennan's hypothesis leads us, as Engels says, to conclude ‘all the exogamous races as having originally been polyandrous’. In this situation, though the mother is known, the father is not. Kinship is taken from the female line and mother's right prevails. This also suggests that patriarchal power must have evolved later and any concept of authority related to male descent is subsequent development.

Edwards Jenks also supported primacy of the matriarchal family and maintained that motherhood in such cases is a fact, while paternity is only an opinion’.65 According to Jenks, tribe was the earliest group from which other forms of social organizations like clan and then family came. However, both McLennan and Jenks are concerned only with the earliest form of social organization and do not at all deal with the origin and development of the state.

Henry Maine is one of the early contributors of evolutionary theory. His book, Early History of Institutions is considered an important study in social evolution. He supported patriarchal hypothesis and suggested that the early form of social organization was the family, which was characterized by the authority of the male descendant. The eldest male descendant must have become protector and ruler of patriarchal family. He supported the idea of consanguinity/kinship-based social groups and stated that one's status in the kin-group (father, mother, son, daughter, family head, elder and younger brother, etc.) determined their mutual relationships. As such, status was considered as the initial stage of social relationship. From the paternal authority and status-based social relationships, Maine traces further evolution of social organization. According to Maine, ‘the elementary group is family connected by common subjection to the highest male ascendant. The aggregation of families forms the Gens or House. The aggregation of Houses makes the Tribe. The aggregation of Tribes constitutes the Commonwealth.’66 Maine's primary observation in this regard could be said to be what Engels says, that ‘entire progress in comparison with previous epochs consists in our having evolved from status to contract, from an inherited state of affairs to one voluntarily contracted …’67 Thus, social evolution from social relationship based on assigned position to one where the person, action and possessions are freely contracted becomes the path from one stage to another.

Interestingly, Maine's proposition in terms of evolution from status to contract has implication for argument of ‘natural rights’ and individual equality in the state of nature propounded by the social contractualists. If status, in terms of an assigned role, was the primary deciding factor in social relationships, the individual's natural rights go without historical evidence. In short, Maine's position is that paternal power and status-based roles were the initial social forms from which higher forms like contract-based social organizations emerged. Paternal authority does not recognize individual rights, but evolution in the form of the authority of the State does recognize individual rights.

Contrary to Maine, Edward Jenks treats tribe as the earliest form of social organization, from which clan and finally the family evolved. Jenks supports the matriarchal form of authority according to which polyandry, mother right and females succession were primary features of social groups. To support his contention, he cited the examples of certain groups in Australia and Malay Archipelago.68 Matriarchal (both matrilineal and matrilocal) societies are still found in many parts of the world, including India. The female-based societies of Khasi Hills of Meghalaya and also in parts of Kerala could be few examples. For Jenks, then mother's right-based social group was the initial stage, which later gave way to a patriarchal society.