Chapter 17. Programming ASP.NET Applications

Developers are writing more and more of their applications to run over the Web and to be seen in a browser. The most popular technology for doing so is ASP.NET, and with AJAX (and now Silverlight), much of the application can be run client-side.

There are many obvious advantages to web-based applications. For one, you don’t have to create as much of the user interface; you can let Internet Explorer and other browsers handle a lot of the work for you. Another advantage is that distribution of the application and of revisions is often faster, easier, and less expensive. Most important, a web application can be run on any platform by any user at any location, which is harder to do (though not impossible) with smart-client applications.

Another advantage of web applications is distributed processing (though smart-client applications are making inroads). With a web-based application, it is easy to provide server-side processing, and the Web provides standardized protocols (e.g., HTTP, HTML, and XML) to facilitate building n-tier applications.

The focus of this chapter is where ASP.NET and C# programming intersect: the creation of Web Forms and their event handlers. For intensive coverage of ASP.NET, please see either Programming ASP.NET by myself and Dan Hurwitz or Learning ASP.NET 2.0 with AJAX by Jesse Liberty et al. (both published by O’Reilly).

Web Forms Fundamentals

Web Forms bring Rapid Application Development (RAD) to the creation of web applications. From within Visual Studio or Visual Web Developer, you drag-and-drop controls onto a form and write the supporting code in code-behind pages. The application is deployed to a web server (typically IIS, which is shipped with most versions of Windows, and Cassini, which is built into Visual Studio for testing your application), and users interact with the application through a standard browser.

Web Forms implement a programming model in which web pages are dynamically generated on a web server for delivery to a browser over the Internet. With Web Forms, you create an ASPX page with more or less static content consisting of HTML and web controls, as well as AJAX and Silverlight, and you write C# code to add additional dynamic content. The C# code runs on the server for the standard ASPX event handlers and on the client for the Silverlight event handlers (JavaScript is used for standard AJAX event handlers), and the data produced is integrated with the declared objects on your page to create an HTML page that is sent to the browser.

You should pick up the following three critical points from the preceding paragraph and keep them in mind for this entire chapter:

Web pages can have both HTML and web controls (described later).

Processing may be done on the server or on the client, in managed code or in unmanaged code, or via a combination.

Typical ASP.NET controls produce standard HTML for the browser.

Web Forms divide the user interface into two parts: the visual part or user interface (UI), and the logic that lies behind it. This is called code separation; and it is a good thing.

Tip

From version 2.0 of ASP.NET, Visual Studio takes advantage of partial classes, allowing the code-separation page to be far simpler than it was in version 1.x. Because the code-separation and declarative pages are part of the same class, there is no longer a need to have protected variables to reference the controls of the page, and the designer can hide its initialization code in a separate file.

The UI page for ASP.NET pages is stored in a file with the extension .aspx. When you run the form, the server generates HTML sent to the client browser. This code uses the rich Web Forms types found in the System.Web and System.Web.UI namespaces of the .NET FCL, and the System.Web.Extension namespace in Microsoft ASP.NET AJAX.

With Visual Studio, Web Forms programming couldn’t be simpler: open a form, drag some controls onto it, and write the code to handle events. Presto! You’ve written a web application.

On the other hand, even with Visual Studio, writing a robust and complete web application can be a daunting task. Web Forms offer a very rich UI; the number and complexity of web controls have greatly multiplied in recent years, and user expectations about the look and feel of web applications have risen accordingly.

In addition, web applications are inherently distributed. Typically, the client will not be in the same building as the server. For most web applications, you must take network latency, bandwidth, and network server performance into account when creating the UI; a round trip from client to host might take a few seconds.

Tip

To simplify this discussion, and to keep the focus on C#, we’ll ignore client-side processing for the rest of this chapter, and focus on server-side ASP.NET controls.

Web Forms Events

Web Forms are event-driven. An event represents the idea that “something happened” (see Chapter 12 for a full discussion of events).

An event is generated (or raised) when the user clicks a button, or selects from a listbox, or otherwise interacts with the UI. Events can also be generated by the system starting or finishing work. For example, if you open a file for reading, the system raises an event when the file has been read into memory.

The method that responds to the event is called the event handler. Event handlers are written in C#, and are associated with controls in the HTML page through control attributes.

By convention, ASP.NET event handlers return void and take two parameters. The first parameter represents the object raising the event. The second, called the event argument, contains information specific to the event, if any. For most events, the event argument is of type EventArgs, which doesn’t expose any properties. For some controls, the event argument might be of a type derived from EventArgs that can expose properties specific to that event type.

In web applications, most events are typically handled on the server and, therefore, require a round trip. ASP.NET supports only a limited set of events, such as button clicks and text changes. These are events that the user might expect to cause a significant change, as opposed to Windows events (such as mouse-over) that might happen many times during a single user-driven task.

Postback versus nonpostback events

Postback events are those that cause the form to be posted back to the server immediately. These include click-type events, such as the button Click event. In contrast, many events (typically change events) are considered nonpostback in that the form isn’t posted back to the server immediately. Instead, the control caches these events until the next time a postback event occurs.

Tip

You can force controls with nonpostback events to behave in a postback manner by setting their AutoPostBack property to true.

State

A web application’s state is the current value of all the controls and variables for the current user in the current session. The Web is inherently a “stateless” environment. This means that every post to the server loses the state from previous posts, unless the developer takes great pains to preserve this session knowledge. ASP.NET, however, provides support for maintaining the state of a user’s session.

Whenever a page is posted to the server, the server re-creates it from scratch before it is returned to the browser. ASP.NET provides a mechanism that automatically maintains state for server controls (ViewState) independent of the HTTP session. Thus, if you provide a list, and the user has made a selection, that selection is preserved after the page is posted back to the server and redrawn on the client.

Tip

The HTTP session maintains the illusion of a connection between the user and the web application, despite the fact that the Web is a stateless, connectionless environment.

Web Forms Life Cycle

Every request for a page made to a web server causes a chain of events at the server. These events, from beginning to end, constitute the life cycle of the page and all its components. The life cycle begins with a request for the page, which causes the server to load it. When the request is complete, the page is unloaded. From one end of the life cycle to the other, the goal is to render appropriate HTML output back to the requesting browser. The life cycle of a page is marked by the following events, each of which you can handle yourself or leave to default handling by the ASP.NET server:

- Initialize

Initialize is the first phase in the life cycle for any page or control. It is here that any settings needed for the duration of the incoming request are initialized.

- Load

ViewState The

ViewStateproperty of the control is populated. TheViewStateinformation comes from a hidden variable on the control, used to persist the state across round trips to the server. The input string from this hidden variable is parsed by the page framework, and theViewStateproperty is set. You can modify this via theLoadViewState( )method. This allows ASP.NET to manage the state of your control across page loads so that each control isn’t reset to its default state each time the page is posted.- Process Postback Data

During this phase, the data sent to the server in the posting is processed. If any of this data results in a requirement to update the

ViewState, that update is performed via theLoadPostData( )method.- Load

CreateChildControls( )is called, if necessary, to create and initialize server controls in the control tree. State is restored, and the form controls contain client-side data. You can modify the load phase by handling theLoadevent with theOnLoad( )method.- Send Postback Change Modifications

If there are any state changes between the current state and the previous state, change events are raised via the

RaisePostDataChangedEvent( )method.- Handle Postback Events

The client-side event that caused the postback is handled.

- PreRender

This is your last chance to modify the output prior to rendering, using the

OnPreRender( )method.- Save State

Near the beginning of the life cycle, the persisted view state was loaded from the hidden variable. Now it is saved back to the hidden variable, persisting as a string object that will complete the round trip to the client. You can override this using the

SaveViewState( )method.- Render

This is where the output to be sent back to the client browser is generated. You can override it using the

Rendermethod.CreateChildControls( )is called, if necessary, to create and initialize server controls in the control tree.- Dispose

This is the last phase of the life cycle. It gives you an opportunity to do any final cleanup and release references to any expensive resources, such as database connections. You can modify it using the

Dispose( )method.

Creating a Web Form

To create the simple Web Form that we will use in the next example, start up Visual Studio .NET and select File → New Web Site. In the New Web Site dialog, choose ASP.NET Web Site from the templates, File System for the location (you can also create web sites remotely using HTTP or FTP), and Visual C# as your language. Give your web site a location and a name and choose your .NET Framework, as shown in Figure 17-1.

Visual Studio creates a folder named ProgrammingCSharpWeb in the directory you’ve indicated, and within that directory it creates your Default.aspx page (for the user interface), Default.aspx.cs file (for your code), web.config file (for web site configuration settings), and an App_Data directory (currently empty but often used to hold .mdb files or other data-specific files).

Tip

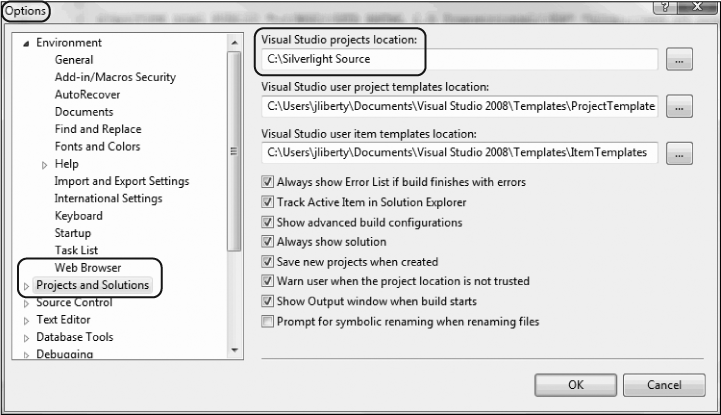

Although Visual Studio no longer uses projects for web applications, it does keep solution files to allow you to quickly return to a web site or desktop application you’ve been developing. The solution files are kept in a directory you can designate through the Tools → Options window, as shown in Figure 17-2.

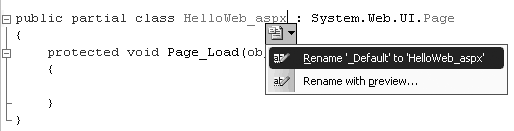

Code-Behind Files

Let’s take a closer look at the .aspx and code-behind files that Visual Studio creates. Start by renaming Default.aspx to HelloWeb.aspx. To do this, close Default.aspx and then right-click its name in the Solution Explorer. Choose Rename, and enter the name HelloWeb.aspx. That renames the file, but not the class. To rename the class, right-click the .aspx page, choose View Code in the code page, and then rename the class HelloWeb_aspx. You’ll see a small line next to the name. Click it, and you’ll open the smart tag that allows you to rename the class. Click “Rename '_Default’ to ‘HelloWeb_aspx’” and Visual Studio ensures that every occurrence of Default_aspx is replaced with its real name, as shown in Figure 17-3.

Within the HTML view of HelloWeb.aspx, you see that a form has been specified in the body of the page using the standard HTML form tag:

<form id="form1" runat="server">

Web Forms assume that you need at least one form to manage the user interaction, and it creates one when you open a project. The attribute runat="server" is the key to the server-side magic. Any tag that includes this attribute is considered a server-side control to be executed by the ASP.NET Framework on the server. Within the form, Visual Studio has opened div tags to facilitate placing your controls and text.

Having created an empty Web Form, the first thing you might want to do is add some text to the page. By switching to the Source view, you can add script and HTML directly to the file just as you could with classic ASP. Adding to the body segment of the .aspx page the highlighted line in the following code snippet:

<%@ Page Language="C#" AutoEventWireup="true" CodeFile="HelloWeb.aspx.cs"

Inherits="HelloWeb_aspx" %>

<!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD XHTML 1.0 Transitional//EN"

"http://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml1/DTD/xhtml1-transitional.dtd">

<html xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml">

<head runat="server">

<title>Hello Web Page</title>

</head>

<body>

<form id="form1" runat="server">Hello World! It is now <% = DateTime.Now.ToString( ) %>

<div>

</div>

</form>

</body>

</html>will cause it to display a greeting and the current local time:

Hello World! It is now 9/9/2009 5:24:16 PM

The <% and %> marks work just as they did in classic ASP, indicating that code falls between them (in this case, C#). The = sign immediately following the opening tag causes ASP.NET to display the value, just like a call to Response.Write( ). You could just as easily write the line as:

Hello World! It is now <% Response.Write(DateTime.Now.ToString( )); %>

Run the page by pressing F5.

Adding Controls

You can add server-side controls to a Web Form in three ways: by writing HTML into the HTML page, by dragging controls from the toolbox to the Design page, or by programmatically adding them at runtime. For example, suppose you want to use buttons to let the user choose one of three shippers provided in the Northwind database. You can write the following HTML into the <form> element in the HTML window:

<asp:RadioButton GroupName="Shipper" id="Speedy"

text = "Speedy Express" Checked="True" runat="server">

</asp:RadioButton>

<asp:RadioButton GroupName="Shipper" id="United"

text = "United Package" runat="server">

</asp:RadioButton>

<asp:RadioButton GroupName="Shipper" id="Federal"

text = "Federal Shipping" runat="server">

</asp:RadioButton>The asp tags declare server-side ASP.NET controls that are replaced with normal HTML when the server processes the page. When you run the application, the browser displays three radio buttons in a button group; selecting one deselects the others.

You can create the same effect more easily by dragging three buttons from the Visual Studio toolbox onto the form, or to make life even easier, you can drag a radio button list onto the form, which will manage a set of radio buttons declaratively. When you do, the smart tag is opened, and you are prompted to choose a data source (which allows you to bind to a collection; perhaps one you’ve obtained from a database) or to edit items. Clicking Edit Items opens the ListItem Collection Editor, where you can add three radio buttons.

Each radio button is given the default name ListItem, but you may edit its text and value in the ListItem properties, where you can also decide which of the radio buttons is selected, as shown in Figure 17-5.

You can improve the look of your radio button list by changing properties in the Properties window, including the font, colors, number of columns, repeat direction (vertical is the default), and so forth, as well as by utilizing Visual Studio’s extensive support for CSS styling, as shown in Figure 17-6.

In Figure 17-6, you can just see that in the lower-righthand corner you can switch between the Properties window and the Styles window. Here, we’ve used the Properties window to set the tool tip, and the Styles window to create and apply the ListBox style, which creates the border around our listbox and sets the font and font color. We’re also using the split screen option to look at Design and Source at the same time.

The tag indications (provided automatically at the bottom of the window) show us our location in the document; specifically, inside a ListItem, within the ListBox which is inside a div which itself is inside form1. Very nice.

Server Controls

Web Forms offer two types of server-side controls. The first is server-side HTML controls. These are HTML controls that you tag with the attribute runat=Server.

The alternative to marking HTML controls as server-side controls is to use ASP.NET Server Controls, also called ASP controls or web controls. ASP controls have been designed to augment and replace the standard HTML controls. ASP controls provide a more consistent object model and more consistently named attributes. For example, with HTML controls, there are myriad ways to handle input:

<input type="radio"> <input type="checkbox"> <input type="button"> <input type="text"> <textarea>

Each behaves differently and takes different attributes. The ASP controls try to normalize the set of controls, using attributes consistently throughout the ASP control object model. Here are the ASP controls that correspond to the preceding HTML server-side controls:

<asp:RadioButton> <asp:CheckBox> <asp:Button> <asp:TextBox rows="1"> <asp:TextBox rows="5">

The remainder of this chapter focuses on ASP controls.

Data Binding

Various technologies have offered programmers the opportunity to bind controls to data so that as the data was modified, the controls responded automatically. However, as Rocky used to say to Bullwinkle, “That trick never works.” Bound controls often provided the developer with severe limitations in how the control looked and performed.

The ASP.NET designers set out to solve these problems and provide a suite of robust data-bound controls, which simplify display and modification of data, sacrificing neither performance nor control over the UI. From version 2.0, they have expanded the list of bindable controls and provided even more out-of-the-box functionality.

In the previous section, you hardcoded radio buttons onto a form, one for each of three shippers in the Northwind database. That can’t be the best way to do it; if you change the shippers in the database, you have to go back and rewire the controls. This section shows you how you can create these controls dynamically and then bind them to data in the database.

You might want to create the radio buttons based on data in the database because you can’t know at design time what text the buttons will have, or even how many buttons you’ll need. To accomplish this, you’ll bind your RadioButtonList to a data source.

Create a new page (right-click on the project, and choose Add New Item; put your form in split view; from the dialog box, choose Web Form). Name the new Web Form DisplayShippers.aspx.

From the toolbox, drag a RadioButtonList onto the new form, either onto the design pane, or within the <div> in the Source view.

Tip

If you don’t see the radio buttons on the left of your work space, try clicking on View → Toolbox to open the toolbox, and then clicking on the Standard tab of the toolbox. Right-click on any control in the toolbox, and choose Sort Items Alphabetically.

In the Design pane, click on the new control’s smart tag. Then, select Choose Data Source. The Choose a Data Source dialog opens, as shown in Figure 17-7.

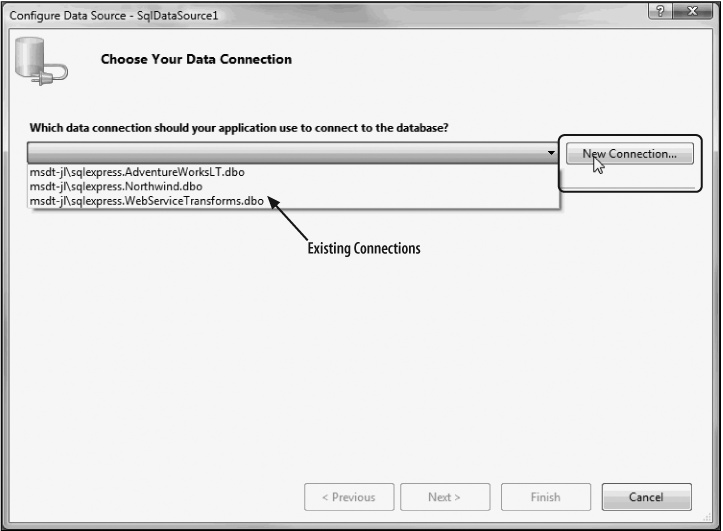

Drop down the “Select a data source” menu and choose <New Data Source>. You are then prompted to choose a data source from the datatypes on your machine. Select Database, assign it an ID, and click OK. The Configure Data Source dialog box opens, as shown in Figure 17-8.

Choose an existing connection, or in this case, choose New Connection to configure a new data source, and the Add Connection dialog opens.

Fill in the fields: choose your server name, how you want to log in to the server (if in doubt, choose Windows Authentication), and the name of the database (for this example, Northwind). Be sure to click Test Connection to test the connection. When everything is working, click OK, as shown in Figure 17-9.

After you click OK, the connection properties will be filled in for the Configure Data Source dialog. Review them, and if they are OK, click Next. On the next wizard page, name your connection (e.g., NorthWindConnectionString) if you want to save it to your web.config file.

When you click Next, you’ll have the opportunity to specify the tables and columns you want to retrieve, or to specify a custom SQL statement or stored procedure for retrieving the data.

Open the Table list, and scroll down to Shippers. Select the ShipperID and CompanyName fields, as shown in Figure 17-10.

Tip

While you are here, you may want to click the Advanced button just to see what other options are available to you.

Click Next, and test your query to see that you are getting back the values you expected, as shown in Figure 17-11.

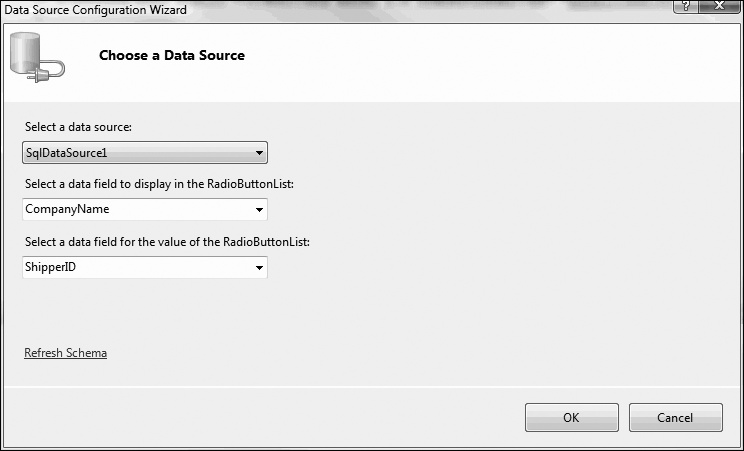

It is now time to attach the data source you’ve just built to the RadioButtonList. A RadioButtonList (like most lists) distinguishes between the value to display (e.g., the name of the delivery service) and the value of that selection (e.g., the delivery service ID). Set these fields in the wizard, using the drop down, as shown in Figure 17-12.

You can improve the look and feel of the radio buttons by binding to the Shippers table, clicking the Radio Button list, and then setting the list’s properties and CSS styles, as shown in Figure 17-13.

Examining the Code

Before moving on, there are a few things to notice. When you press F5 to run this application, it appears in a web browser, and the radio buttons come up as expected. Choose View → Source, and you’ll see that what is being sent to the browser is simple HTML, as shown in Example 17-1.

<!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD XHTML 1.0 Transitional//EN"

"http://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml1/DTD/xhtml1-transitional.dtd">

<html xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml">

<head><title>

Display Shippers

</title>

<style type="text/css">

.RadioButtonStyle

{

font-family: Verdana;

font-size: medium;

font-weight: normal;

font-style: normal;

border: medium groove #FF0000;

}

</style>

</head>

<body>

<form name="form1" method="post" action="DisplayShippers.aspx" id="form1">

<div>

<input type="hidden" name="_ _VIEWSTATE" id="_ _VIEWSTATE"

value="/wEPDwUJMzU1NzcyMDk0D2QWAgIDD2QWAgIBDxAPFgIeC18hRGF0YUJvdW5kZ2QQFQMOU3BlZWR5

IEV4cHJlc3MOVW5pdGVkIFBhY2thZ2UQRmVkZXJhbCBTaGlwcGluZxUDATEBMgEzFCsDA2dnZ2RkZA9Nylp

g2lObPr0KzM1NvwXJoMBn" />

</div>

<div>

<table id="RadioButtonList1" border="0">

<tr>

<td><input id="RadioButtonList1_0" type="radio"

name="RadioButtonList1" value="1" />

<label for="RadioButtonList1_0">Speedy Express</label></td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td><input id="RadioButtonList1_1" type="radio"

name="RadioButtonList1" value="2" />

<label for="RadioButtonList1_1">United Package</label></td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td><input id="RadioButtonList1_2" type="radio"

name="RadioButtonList1" value="3" />

<label for="RadioButtonList1_2">Federal Shipping</label></td>

</tr>

</table>

</div>

<div>

<input type="hidden" name="_ _EVENTVALIDATION" id="_ _EVENTVALIDATION"

value="/wEWBQLIyMfLBQL444i9AQL544i9AQL644i9AQL3jKLTDcEXOHLsO/LFFixl7k4g2taGl6Qy" />

</div></form>

</body>

</html>Notice that the HTML has no RadioButtonList; it has a table, with cells, within which are standard HTML input objects and labels. ASP.NET has translated the developer controls to HTML understandable by any browser.

Warning

A malicious user may create a message that looks like a valid post from your form, but in which he has set a value for a field you never provided in your form. This may enable him to choose an option not properly available (e.g., a Premier-customer option), or even to launch a SQL injection attack. You want to be especially careful about exposing important data such as primary keys in your HTML, and take care that what you receive from the user may not be restricted to what you provide in your form. For more information on secure coding in .NET, see http://msdn.microsoft.com/security/.

Adding Controls and Events

By adding just a few more controls, you can create a complete form with which users can interact. You will do this by adding a more appropriate greeting (“Welcome to NorthWind”), a text box to accept the name of the user, two new buttons (Order and Cancel), and text that provides feedback to the user. Figure 17-14 shows the finished form.

This form won’t win any awards for design, but its use will illustrate a number of key points about Web Forms.

Tip

I’ve never known a developer who didn’t think he could design a perfectly fine UI. At the same time, I never knew one who actually could. UI design is one of those skills (such as teaching) that we all think we possess, but only a few very talented folks are good at it. As developers, we know our limitations: we write the code, and someone else lays it out on the page and ensures that usability issues are reviewed. For more on this, I highly recommend every programmer read Don’t Make Me Think: A Common Sense Approach to Web Usability by Steve Krug (New Riders Press) and Why Software Sucks . . . and What You Can Do About It by David Platt (Addison-Wesley).

Example 17-2 is the complete HTML for the .aspx file.

<%@ Page Language="C#" AutoEventWireup="true" CodeFile="DisplayShippers.aspx.cs"

Inherits="DisplayShippers" %>

<!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD XHTML 1.0 Transitional//EN"

"http://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml1/DTD/xhtml1-transitional.dtd">

<html xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml">

<head runat="server">

<title>Choose Shippers</title>

<style type="text/css">

.RadioButtonStyle

{

font-family: Verdana;

font-size: medium;

font-weight: normal;

font-style: normal;

border: medium groove #FF0000;

}

</style>

</head>

<body>

<form id="form1" runat="server">

<table style="width: 300px; height: 33px">

<tr>

<td colspan="2" style="height: 20px">Welcome to NorthWind</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td>Your name:</td>

<td><asp:TextBox ID="txtName" Runat=server></asp:TextBox></td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td>Shipper:</td>

<td>

<asp:RadioButtonList ID="rblShippers" runat="server"

DataSourceID="SqlDataSource1" DataTextField="CompanyName"

DataValueField="ShipperID">

</asp:RadioButtonList>

</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td><asp:Button ID="btnOrder" Runat=server Text="Order"

onclick="btnOrder_Click" /></td>

<td><asp:Button ID="btnCancel" Runat=server Text="Cancel" /></td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td colspan="2"><asp:Label id="lblMsg" runat=server></asp:Label></td>

</tr>

</table>

<asp:SqlDataSource ID="SqlDataSource1" runat="server"

ConnectionString="<%$ ConnectionStrings:NorthwindConnectionString %>"

SelectCommand="SELECT [ShipperID], [CompanyName] FROM [Shippers]">

</asp:SqlDataSource>

</form>

</body>

</html>When the user clicks the Order button, you’ll check that the user has filled in his name, and you’ll also provide feedback on which shipper was chosen. Remember, at design time, you can’t know the name of the shipper (this is obtained from the database), so you’ll have to ask the Listbox for the chosen name (and ID).

To accomplish all of this, switch to Design mode, and double-click the Order button. Visual Studio will put you in the code-behind page, and will create an event handler for the button’s Click event.

Tip

To simplify this code, we will not validate that the user has entered a name in the text box. For more on the controls that make such validation simple, please see Programming ASP.NET.

You add the event-handling code, setting the text of the label to pick up the text from the text box, and the text and value from the RadioButtonList:

protected void btnOrder_Click(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

lblMsg.Text = "Thank you " + txtName.Text.Trim( ) +

". You chose " + rblShippers.SelectedItem.Text +

" whose ID is " + rblShippers.SelectedValue;

}When you run this program, you’ll notice that none of the radio buttons are selected. Binding the list did not specify which one is the default. There are a number of ways to do this, but the easiest is to add a single line in the Page_Load method that Visual Studio created:

protected void Page_Load(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

rblShippers.SelectedIndex = 0;

}This sets the RadioButtonList’s first radio button to Selected. The problem with this solution is subtle. If you run the application, you’ll see that the first button is selected, but if you choose the second (or third) button and click OK, you’ll find that the first button is reset. You can’t seem to choose any but the first selection. This is because each time the page is loaded, the OnLoad event is run, and in that event handler you are (re-)setting the selected index.

The fact is that you only want to set this button the first time the page is selected, not when it is posted back to the browser as a result of the OK button being clicked.

To solve this, wrap the setting in an if statement that tests whether the page has been posted back:

protected override void OnLoad(EventArgs e)

{

if (!IsPostBack)

{

rblShippers.SelectedIndex = 0;

}

}When you run the page, the IsPostBack property is checked. The first time the page is posted, this value is false, and the radio button is set. If you click a radio button and then click OK, the page is sent to the server for processing (where the btnOrder_Click handler is run), and then the page is posted back to the user. This time, the IsPostBack property is true, and thus the code within the if statement isn’t run, and the user’s choice is preserved, as shown in Figure 17-15.

Example 17-3 shows the complete code-behind form.

using System;

public partial class DisplayShippers : System.Web.UI.Page

{

protected void Page_Load(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

if (!IsPostBack)

{

rblShippers.SelectedIndex = 0;

}

}

protected void btnOrder_Click(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

lblMsg.Text = "Thank you " + txtName.Text.Trim( ) +

". You chose " + rblShippers.SelectedItem.Text +

" whose ID is " + rblShippers.SelectedValue;

}

}