6

Reviewing the Project

| Q: | How do we improve organization-wide project management? |

| A: | Share project experiences through post-project review. |

In this chapter, you will learn how to:

• perform a post-project review for every project to ensure the knowledge management of project intellectual capital.

In previous chapters, you read how to create a project charter in the design phase, create a project schedule in the plan phase, and then implement and adjust the project schedule in the manage phase. When the project is completed, it is tempting to just move on. It’s normal to be pretty sick of it at this point. As project teams move quickly from finished projects to new projects, often no time is taken to reflect on what happened or the ramifications for future project work. As a learning expert, however, you know that learning (a change in behavior) occurs through reflection following mistakes. The post-project review discussed in this chapter holds the key to identifying lessons learned and then, most importantly, changing the behavior you bring to future project work. It is only through this activity that true project management expertise accumulates in an organization and in each person. Personal reflection creates personal improvement, so your time is well invested.

Certainly, personal reflection on project work is of great benefit; just thinking about the project on your own can create a personal behavior change that will improve your own expertise. The true leverage comes, however, through project team reflection. In The Knowledge-Creating Company: How Japanese Companies Create the Dynamics of Innovation (Nonaka, Takeuchi, and Takeuchi 1995), the authors explain the life cycle of knowledge: creation, exchange, transformation, and then recycling, returning to creation with more knowledge. Knowledge creation and transformation occur when project teams reflect on their project experiences together. As their experiences are vocalized and exchanged, new knowledge is created through action plans for the future. Using a post-project review approach ensures that the life cycle of knowledge continues organizationally.

Making Change Work, an IBM survey in October 2008, found that only 40 percent of projects meet schedule, budget, and quality goals. In addition, the biggest barriers to success were people factors: changing mindsets (58 percent), corporate culture (49 percent), and lack of senior management support (32 percent). The influence of people factors on project success provides support for post-project reviews. Unfortunately, in practice, little post-project reflection occurs. Project barriers can only be mitigated through awareness-driving knowledge management—by identifying them in a post-project review and sharing them with future project teams.

Your project will not be exactly the same as someone else’s, and you can be sure that something new will surprise you on every project. All the knowledge from all the previous teams’ experiences cannot save you from surprise glitches. But certain events seem to occur in every project, such as scope creep and communication problems. These problems will be glaringly obvious looking back during a post-project review. In the midst of doing the project, you may not have noticed what was really causing your rework. In this chapter, you will learn about multiple post-project review approaches and information on using systems thinking to review a project.

Post-Project Review Approaches

There are many ways to perform post-project review, as well as many alternatives depending on the type of project and the availability of the participants. Here’s a list of some very simple debrief questions that work well with small in-person meetings:

• What did you learn about project management?

• What would you do differently if you did this project again?

• What would you do the same way?

• What other lessons did you learn?

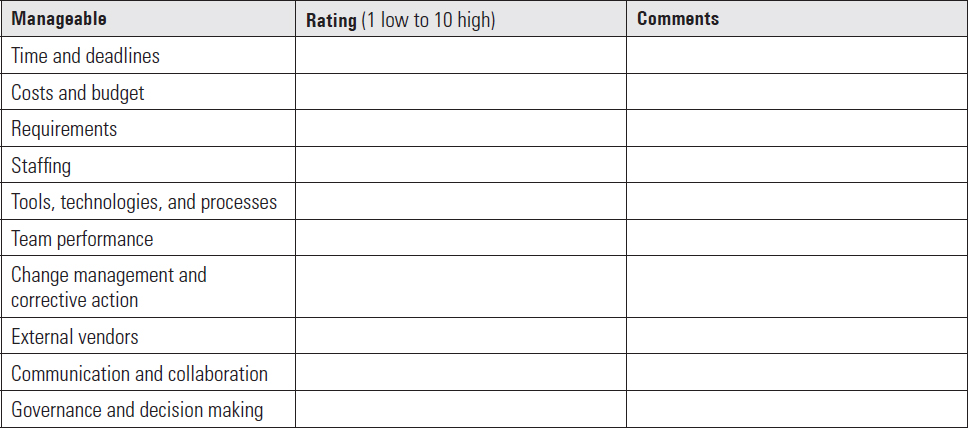

The post-project review gathers information about the “manageables” of a project. Figure 6-1 is a sample template for this type of project—the manageables are listed with a scale to rate the success of each, instead of open-ended questions. You may want to remove or add other rows. Use an online survey tool to gather the data.

Figure 6-1. Sample Post-Project Review With Rating Scale

Please rate the usefulness of each manageable on our project.

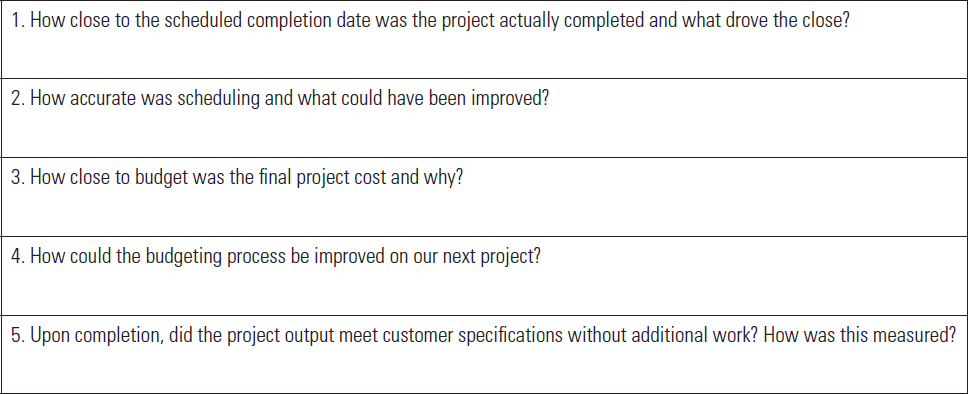

Instead of ranking, you may want to capture similar data with open-ended questions. This is more time consuming for your participants, and thus reduces your feedback, but it will also improve the quality of feedback (see Figure 6-2 for a sample).

Figure 6-2. Sample Post-Project Review With Open-Ended Questions

Although fairly standard, this type of survey can suffer from “leading the witness,” or encouraging people to give feedback on things they might not have thought about much unless they were asked.

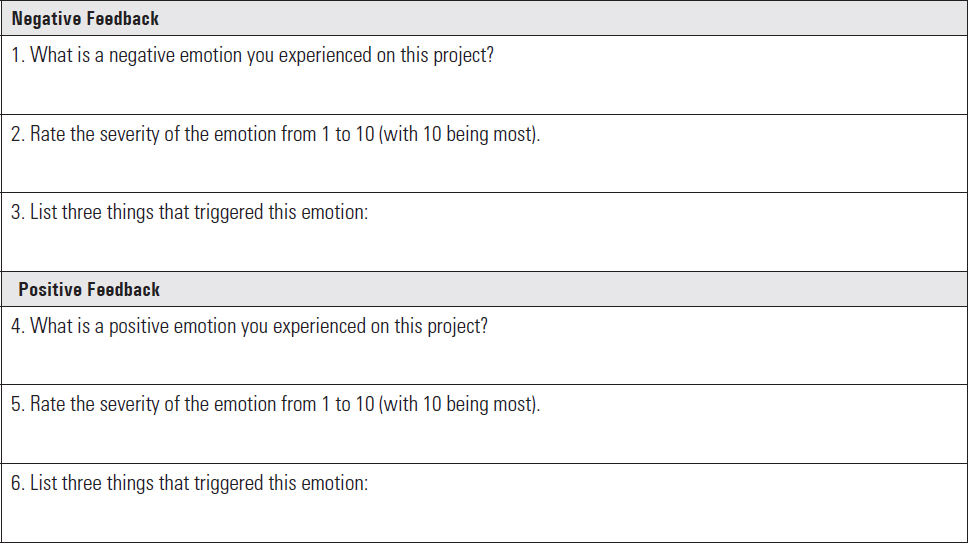

A different approach to getting real feedback from stakeholders about a completed project leverages emotional intelligence. You ask participants to begin with negative emotions and then to describe positive emotions, which allows you to lead them to the real issues they struggled with on the project (see Figure 6-3 for an example). Participants rate the intensity of the emotion on a scale of 1 to 10, with 10 being the most severe. In addition, they list three things that triggered the emotion.

Notice there are no manageables mentioned—each person uncovers what was most important to them, both positive and negative. By starting with an emotion, and then rating the intensity, you lead your stakeholders deeply into their own brain, purposely helping them revisit the experiences that held the most intensity for them. This allows you to get a list of what really bothered and excited them. This approach can also be done immediately after the project or as an online survey later on.

Figure 6-3. Sample Post-Project Review With Emotional Feedback

If you have worked on a large, enterprise project, the lessons are extremely hard and critical to capture. Nobody wants additional meetings after a project is done, especially with the likelihood of some difficult conversations. Consider combining a project celebration with some time for the post-project review.

If you can get people together physically, try using this kinesthetic and emotionally safe exercise to gather a group’s feedback collaboratively. This exercise, based on a facilitation technique created by Thiagi, should take around 30 to 60 minutes.

1. Ask participants to individually reflect on the project by writing quick notes, one on each sticky note. (Time needed: 15 minutes or less depending on meeting constraints.)

2. Ask the participants to put their sticky notes on a wall or whiteboard without speaking to one another. Next, ask them to start grouping similar ideas that they see, regardless of who wrote them, silently. When the grouping is slowing down, ask them to talk together while continuing to create groups of lessons learned. The last step is to have the participants agree on a label (for example, Scope Issues) for each grouping. If you have a large number of participants, divide them into small teams that work in parallel, then combine the results. (Time needed: 30 minutes or less.)

3. Ask a volunteer from each team to explain each group of sticky notes. Challenge the entire group to list a significant lesson learned that can be shared with future project managers. (Time needed: 15 minutes or less.)

If possible, get a neutral facilitator to manage the face-to-face meeting. Project managers are often too close to the issues and their input is too important to also play the role of facilitator.

Using Systems Thinking to Review a Project

For projects that were either mission critical to the company, very problematic, or just very different, investing a little more time capturing the lessons learned creates great benefit. This section explains how to use a learning organization technique called systems thinking. Systems thinking is a group facilitation technique that creates a visual model built with cause-and-effect loops, which represent the different choices that influenced the success of a project. See Peter Senge’s book The Fifth Discipline (1990) for more information on systems thinking and learning organization techniques.

Systems thinking always starts with a “why” question that frames the scope of the challenge. It is a simple and measurable question that asks why a perceived problem is occurring. Creating a good why question—one without bias and blame—is tricky. Notice the differences between good and bad why questions:

• Bad why questions (biased, blaming, and not measurable)

![]() Why is the IT department so difficult to deal with?

Why is the IT department so difficult to deal with?

![]() Why did the software vendor screw this project up?

Why did the software vendor screw this project up?

• Good why questions (neutral and measurable)

![]() Why did this project run months over its initial due date?

Why did this project run months over its initial due date?

![]() Why did stakeholders not attend project status meetings?

Why did stakeholders not attend project status meetings?

![]() Why did learners not register for the course after completion?

Why did learners not register for the course after completion?

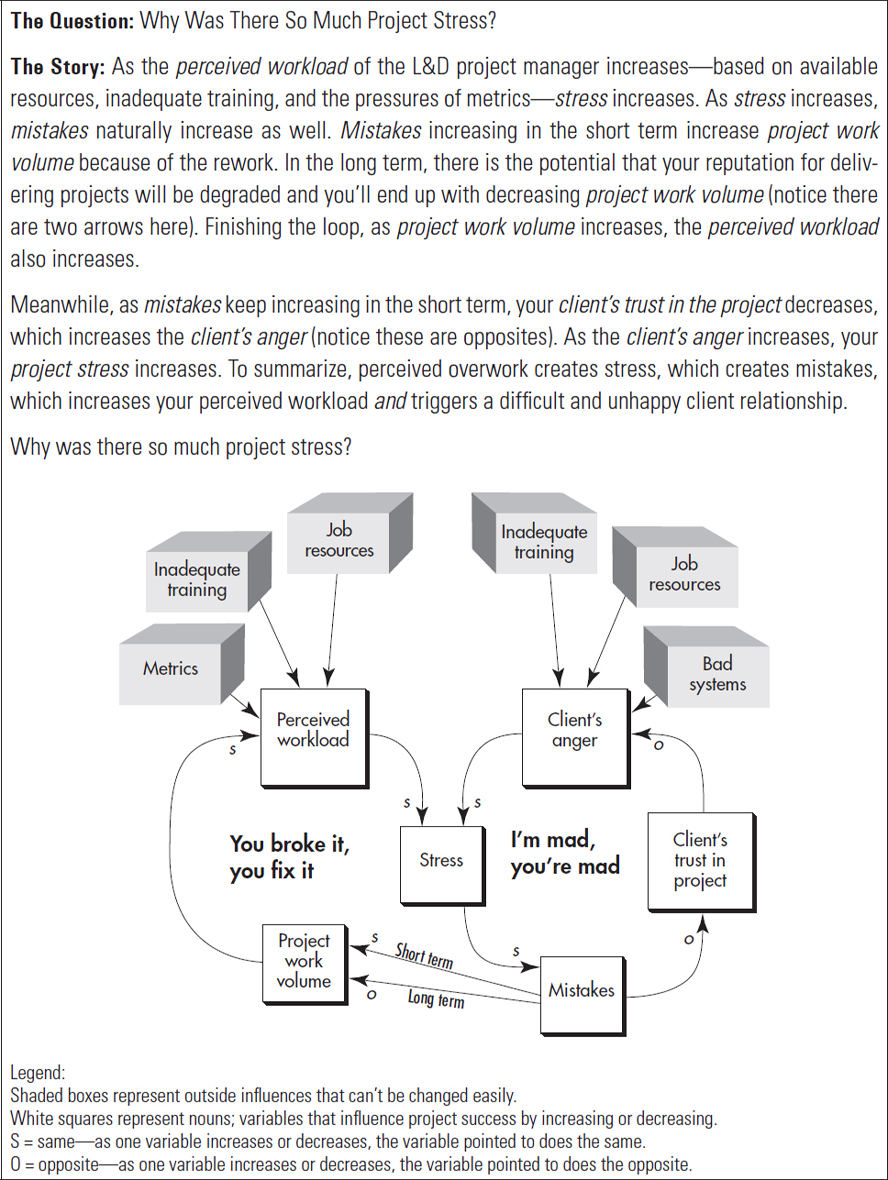

When at a loss, start with the question “Why did this project struggle?” and let the true question evolve as the team proceeds. It is common for the why question to change as you discuss the project more deeply. Keep referring back to the question to see if it still fits. Figure 6-4 shows an overly simple example of a model that answers the question “Why was there so much project stress?”

Once the team agrees that this model tells the “truth” of what happened during the project, it’s time to figure out what you could do to improve the situation. Mistakes foster more mistakes and if the situation continues, the team will lose the project. If you could decrease perceived workload, the other variables will decrease as well, starting a positive cycle of fewer mistakes and reduced workload. But how can you do that? The same would be true with decreasing stress. It seems that reducing stress could really improve project results, but this is not something that most projects work on!

Figure 6-4. Example of a Simple Systems Thinking Model

Here are some other examples for interventions to improve project stress based on Figure 6-4 that a project manager could do:

• Help project team members deal better with stress by helping them be more aware and learn to mitigate.

• Teach project team members to triage and prioritize mistakes so they don’t always add to the project workload.

• Teach project team members how to narrow the scope when mistakes force the project workload to unrealistic levels.

• Manage the customer relationship and customer expectations proactively.

Facilitating this type of session takes an experienced systems thinking facilitator. The sessions can take from a half to a full day, depending on the depth and number of people involved. I recommend that you take time off between the creation of the model and the discussion of the intervention, so people have time to really think about it. It is not recommended that you simply hand the model, without explanation, to future project teams. The model with the “stories” and the proposed interventions are more meaningful when they come from people who were there when it happened.

When creating training, it is important to leave ample time to debrief an exercise. Much of learning occurs in the reflection after the event, not during. Practicing this after a project ends encourages learning that improves your future projects. Even if you only have time to debrief yourself, you will find it valuable and future projects will be affected.

History Tells Us …

All projects have struggles, and looking back at a struggle is no reflection of the inadequacy of any member of a project team. The teams that can look back and learn from struggles will be much more successful in the future than teams that hide from these lessons. The post-project review allows a team and an organization to:

• Build knowledge about success factors of projects for their business.

• Build a team consensus that leaves the participants open, collaborative, and forward-thinking, rather than guilt ridden. This consensus builds bridges for future project teamwork.

• Create a building block for implementing knowledge management in a pragmatic manner so that knowledge can be created, exchanged, and transformed for measurable business return.

Summary

In this chapter, you read about how to review a learning event project once it ends. To review a project requires honest reflection and sharing. Denial is not healthy during or after a project. Now practice the review-phase activities using your own experience.

Practical Exercise

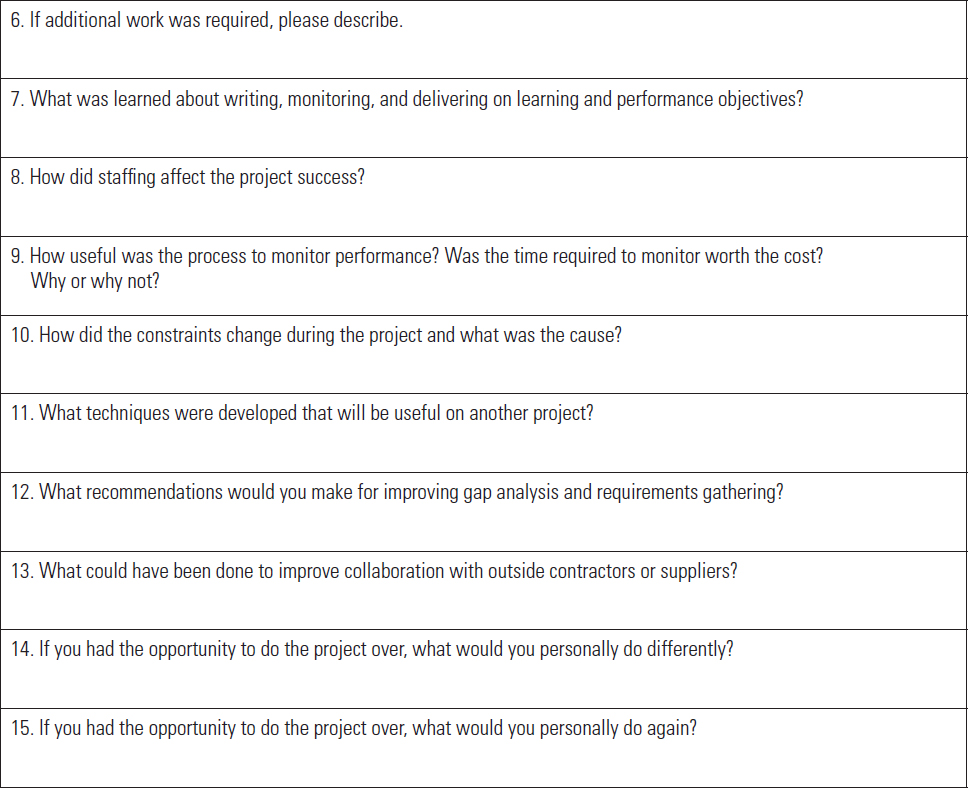

Exercise 6-1. Post-Project Review

Complete the post-project review template on the next page for a project you have worked on by answering each of the questions in the template. Find one other person who was involved with that project, and ask her to reflect on the project, following the template as much as possible, and to share her answers with you.

Use your answers to reflect on the questions below. Write down your answers in the space provided.

What did you learn about project management?

What would you do differently?

What would you do the same way?

Post-Project Review Template

1. How close to the scheduled completion date was the project actually completed and what drove the close? |

|

2. How accurate was scheduling and what could have been improved? |

|

3. How close to budget was the final project cost and why? |

|

4. How could the budgeting process be improved on our next project? |

|

5. Upon completion, did the project output meet customer specifications without additional work? How was this measured? |

|

6. If additional work was required, please describe. |

|

7. What was learned about writing, monitoring, and delivering on learning and performance objectives? |

|

8. How did staffing affect the project success? |

|

9. How useful was the process to monitor performance? Was the time required to monitor worth the cost? |

|

10. How did the constraints change during the project and what was the cause? |

|

11. What techniques were developed that will be useful on another project? |

|

12. What recommendations would you make for improving gap analysis and requirements gathering? |

|

13. What could have been done to improve collaboration with outside contractors or suppliers? |

|

14. If you had the opportunity to do the project over, what would you personally do differently? |

|

15. If you had the opportunity to do the project over, what would you personally do again? |