If problems arise during the life of a project, our first hunch would be that the project was not properly planned. Most of the time our hunch would be correct. Inadequate planning is more the case than the exception. We can only guess why. Perhaps the reason is that senior management and/or the PM and/or the project team are impatient. They want "to get on with it." Possibly some of the people who should be engaged in planning have heard Tom Peters, well-known searcher-for-excellence and management guru, comment that good planning almost never cuts implementation time and that "Ready, Fire, Aim" is the way good businesses do it.

As a matter of fact, Peters is wrong. There is a ton of research that concludes that careful planning is strongly associated with project success—and to the best of our knowledge there is no research that supports the opposite position. Clearly, planning can be overdone, a condition often called "paralysis by analysis." Somewhere in between the extremes is the happy medium that everyone would like to strike, but this chapter does not seek to define the golden mean between no planning and over-planning (Langley, 1995). We do, however, examine the nature of good planning, and we describe proven methods for generating plans that are adequate to the task of leading a project work force from the start of the project to its successful conclusion. We must start by deciding what things should be a part of a project plan.

Before considering how to plan, we should decide why we are planning and what information the plan should contain. The primary function of a project plan is to serve the PM as a map of the route from project start to finish. The plan should include the business case or the organization's expected financial benefits that will accrue as well as the strategic reasons for the project. The plan should contain sufficient information that, at any time, the PM knows what remains to be done, when, with what resources, by whom, when the task will be completed, and what deliverables the output should include. This information must be known at any level of detail from the most general overall level to the minutiae of the smallest subtask. As the project travels the route from start to finish, the PM needs also to know whether or not any changes in project plans are contemplated and whether or not any problems are likely to arise in the future. In other words, the PM needs to know the project's current state and its future expectations. Because PMs are sometimes appointed after the project has begun, the PM also needs to know the project's history to date.

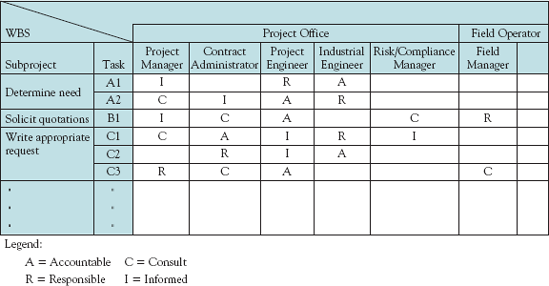

There are several different types of project plans. For example, the PMBOK Project Plan (Chapter 3 and parts of the following chapter of PMBOK) is comprehensive and refers to the Project Charter and all the elements concerning the planning, execution, and control of the project. This is what we refer to as the project plan and is outlined next. (Later we will describe the project itself). It includes the Work Breakdown Structure (WBS), and the RACI matrix (sometimes called a linear responsibility chart) and a few other planning elements which also serve special purposes. As we will see, each of these plays a different role in project management.

The multiple elements required in the project plan fall into one of the following nine categories.

Overview. This section contains a brief description of the project and its deliverables (the latter are the project scope), together with a list of the major milestones or significant events in the project schedule and any constraints on the project scope. It is intended for senior management. This section (or the next) should include the Business Case for the project. The Business Case includes the strategic reasons for the project, its expected profitability and competitive effects as well as the desired scope and any other technical results. The intent of the Business Case is to communicate to project team members (and others) the reasons why the organization is undertaking the project. If not specifically noted elsewhere, the overview can list the project stakeholders, groups (or individuals) who have a legitimate interest in the project or its deliverables.

Objectives. This is a more detailed description of the project's scope, its deliverables and outcomes. Another approach to describing a project's objectives is the project mission statement. While somewhat similar to the Business Case, the focus of the mission statement is to communicate to project team members (and others) what will be done to achieve the project's overall objectives. To foster team understanding of the project as a whole, a representative group of team members and stakeholders are often included in the process of developing the statement of objectives.

General approach. In this section, the technological and managerial approaches to the work are described. An identification of the project as "derivative," "platform," or "breakthrough" might be included, as might the relationship between this project and others being undertaken or contemplated by the organization. Also noted are plans that go beyond the organization's standard management practices. For example, some firms do not allow the use of consultants or subcontractors without special approval.

Contractual aspects. This section contains a complete description of all agreements made with the client or any third party. This list would include all reporting requirements; the technical specifications of all deliverables; agreements on delivery dates; incentives (if any) for performance, for exceeding contractual requirements, and penalties (if any) for noncompliance; specific procedures for making changes in the deliverables, project review dates and procedures; and similar agreements. If relevant, it may contain agreements to comply with legal, environmental, and other constraints on the project work and outputs.

Schedules. Included in this section is an outline of all schedules and milestones. Each task in the project is listed in a project WBS. (The WBS is discussed later in this chapter.) Listed with each task is the time required to perform it. The project schedule is constructed from these data and is included in this section.

Resource requirements. Estimates of project expenses, both capital and operating, are included here. The costs associated with each task are shown, and overhead and fixed charges are listed. Appropriate account numbers to be charged are listed with the relevant cost items. This becomes the project budget, though the PM may use a budget that deletes overhead and some fixed charges for days so-day project management and control. (The details of budget preparation are covered in the next chapter.) In addition, cost monitoring and cost control procedures are described here. The details of materiel acquisition are also detailed in this section.

Personnel. This section covers the details of the project work force. It notes any special skill requirements, necessary training, and special legal arrangements such as security clearances or nondisclosure agreements. Combined with the schedule, it notes the time-phasing of all personnel requirements. Sections 5, 6, and 7 may contain individual notations concerning managerial responsibility for control of each area, or RACI matrix (see later in this chapter) detailing the managerial/informational accountability requirements for each person.

Risk management. "Learn from experience" is a widely ignored adage. This section is an attempt to remedy that condition. Planners should list the major and minor disasters that may strike projects similar to the one being undertaken—late subcontractor deliveries, bad weather, unreasonable deadlines, equipment failure, complex coordination problems, changes in project scope, and similar dire happenings. The argument is made that crises cannot be predicted. The only uncertainty, however, is which of the crises will occur and when. In any case, dealing with crises does not require a which-and-when prediction. In every project there are times when dependence on a subcontractor, or the good health of a software-code writer, or good weather, or machine availability is critical to progress on a project. Contingency plans to deal with such potential crises should be a standard part of the project plan as well as a permanent file in the PMO (or EPMO). A method for quantifying the potential seriousness of risks, Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA), is helpful and is covered in Chapter 4. It is well to remember that no amount of current planning can solve current crises—but developing contingency plans may prevent or soften the impact of some.

Evaluation methods. Descriptions of all project evaluation procedures and quality standards are found in this section. Responsibility and control of all project activities, as detailed in the RACI matrix, may be noted here instead in the Personnel section. Also included are procedures to ensure compliance with all corporate requirements for monitoring, collecting, and storing data on project performance, together with a description of the required project history.

With one important addition, this is the project plan. That addition is known as the Project Charter. The Project Charter contains most, if not all, of the nine items listed above. In practice, the Charter is often an abridged version of the full project plan containing summaries of the budget and schedule details. The major project stakeholders must sign off on the plan. The list of signatories would include a person representing the project sponsor, the client/user, the Project Manager, and the Program Manager if the project is a part of an overall program. In some cases, representatives of other stakeholders may be asked to sign their approval. Clearly, this may require negotiation. Once agreed to, the charter (and the plan) cannot be altered by any signer without acceptance by the others. A bias toward reality requires us to note that different stakeholders have different levels of clout. If senior management and the client both favor a change in the scope of the project, the project manager and his or her team would be well advised to accept the change in good grace unless there is some overriding reason why such a change would be infeasible. Occasionally, stakeholders not directly connected to the organization conducting the project or the client purchasing it can be so demanding that provision is made for them to sign-off on specific changes. Consider, for example, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) and their battles with cosmetic firms over the use of animal testing for cosmetic products. Once completed, the Project Charter becomes a part of the project plan.

Obviously, all of the plan contents listed above are necessary for large, nonroutine projects such as a major software development project. They are not all required for small, routine projects. Specific items such as task schedules, resource/personnel needs, and calendars are needed for any project, large or small, routine or not. Indeed, even if the project is both small and routine, a section dealing with contractual agreements is often needed if the project is for an arm's-length client or if a subcontractor or consultant is involved.

It is hard to overstate the importance of a clear statement of the purpose of the project. It is not, repeat NOT, sufficient to state the project objectives without reference to its purpose. For example, to reach the Pudong International Airport from Shanghai's business center, China built a magnetic levitation (maglev) train that runs every 10 minutes (PMI, April 2004). Reaching speeds over 300 miles an hour, it whisks people to the airport 20 miles away in less than 8 minutes. However, according to the vice- director of the train company, "We are not lucky with ticket sales." The trains are virtually empty. The reason is simple. To meet the time deadline and budget, the train station was located 6 miles outside the city center, requiring lengthy public transportation to get there. The project met its technical, budgetary, and schedule objectives successfully. It failed, however, to meet the needs of the public. China is currently investigating extending the line to the downtown area, but that will be a much more expensive and time- consuming project.

The importance of a contract specifying the process of potential problem solving between the project's principals in addition to the content of project deliverables is made clear in the following example. $74 million of Philadelphia's $567 million Market Street Elevated train system reconstruction project went to PKF Mark III contractors for one portion of the system (PMI, Feb. 2005). The Philadelphia transportation authority (SEPTA), however, maintained that PKF is was far behind schedule, failed to meet the eight milestones of the contract, or complete any of the activities. PKF, in turn, maintained that SEPTA's failure to accept work performed in accordance with the contract constituted a change in project scope, and SEPTA's lack of timely action regarding submittals, requests for information and drawings, claims and change orders are what took the project off schedule. Both groups have gone into litigation to resolve the issue, but the delays of litigation threaten the loss of federal funding for the project. If mediation instead of litigation had been included in the initial contract, the problem might have been more quickly resolved.

One additional use for a careful, complete project plan is when the project may be small and routine, but it is also carried out frequently, as in some maintenance projects. The complete planning process may be conducted to form a template for such projects—with particular emphasis on evaluation methods. With this template, planning similar projects is simple—just fill in the blanks. If changes in the plan are contemplated, the prescribed evaluation methods can be employed. This allows a "continuous improvement" program, sometimes called "rolling wave" planning, to be implemented with ongoing evaluation of suggested changes.

Note

The project plan should contain nine elements: a project overview, a statement of objectives, a description of the technical and managerial approaches to the work, all contractual agreements, schedules of activities, a list of resource requirements or a project budget, personnel requirements, project evaluation methods, and preparations to meet potential problems. When all stakeholders have signed off on the plan, it becomes an operational Project Charter.

A great deal has been written about planning. Some of the literature focuses on the strategic aspect of planning—(e.g., Webster, Reif, and Bracker, 1989) choosing and planning projects that contribute to the organization's goals (cf., the introduction to Section 1.5, in Chapter 1). Another body of writing is directed at the techniques of how to plan rather than what to plan (e.g., Pells, 1993; Prentis, 1989). These techniques, if we are to believe what we read, differ from industry to industry, from subject to subject. Architecture has a planning process; so does software development, as does construction, as well as pharmaceutical R&D projects, and campaigns for raising funds for charity.

As far as we can determine, the way that planning techniques vary in these different cases has more to do with nomenclature than substance. Consider, for example, the following planning process that has been divided into eight distinct steps.

Develop and evaluate the concept of the project. Describe what it is you wish to develop, including its basic performance characteristics, and decide if getting such a deliverable is worthwhile. If so, continue.

Carefully identify and spell out the actual capabilities that the project's deliverable must have to be successful. Design a system (product or service) that will have the requisite capabilities.

Create such a system (product or service), which is to say, build a prototype deliverable.

Test the prototype to see if it does, in fact, have the desired capabilities. If necessary, cycle back to step 3 to modify the prototype and retest it. Continue until the deliverable meets the preset requirements.

Integrate the deliverable into the system for which it was designed. In other words, install the deliverable in its required setting.

Validate the deliverable—which answers the question, "Now that we have installed the deliverable, does it still work properly?"

If the deliverable has been validated, let the client test it. Can the client operate the system? If not, instruct the client.

If the client can operate (and accepts) the deliverable, make sure that the client understands all standard operating and maintenance requirements. Then shake the client's hand, present the client with a written copy of maintenance and operating instructions, give the client the bill, and leave.

Reread the eight steps. Are they not an adequate description of the planning process for the design of a new pick-up truck, of a high-end hotel room, of a restaurant kitchen, of a machine tool, of a line of toys, etc.? They would need a bit of tweaking for some projects. An R&D project would need a more extensive risk analysis. If the project is a new pharmaceutical, for example, it would need toxicity and efficacy testing, and clearance from the FDA, but the general structure of the planning process is still adequate.

The eight steps above were originally written to describe the planning process for computer software (Aaron, Bratta, and Smith, 1993). There seem to be as many different planning sequences and steps as there are authors writing about planning. Almost all of them, regardless of the number of steps, meet the same criteria if they are meant to guide a project to a successful conclusion. The final plan must have the elements described in the previous section of this chapter.

Note

There are many techniques for developing a project plan and Project Charter. They are fundamentally similar. All of them use a systematic analysis to identify and list the things that must be undertaken in order to achieve the project's objectives, to test and validate the plan, and to deliver it to the user.

This section deals with the problem of determining and listing the various tasks that must be accomplished in order to complete a project. The important matters of generating a project budget and developing a precise project schedule are left to succeeding chapters, though much of the raw material for doing those important things will come from the planning process described here.

Once senior management has decided to fund a major project, or a highly important small project, a project launch meeting should be called. Preparation for this meeting is required (Knutson, 1995; Martin and Tate, 1998).

When a PM is appointed to head a new project, the PM's first job is to review the project objectives (project scope plus expected desirable outcomes that accrue to stakeholders from matters beyond the project's deliverables) with the senior manager who has fundamental responsibility for the project. The purpose of this interview is threefold: (1) to make sure that the PM understands the expectations that the organization, the client, and other stakeholders have for the project; (2) to identify those among the senior managers (in addition to the manager who is party to this interview) who have a major interest in the project; and (3) to determine if anything about the project is atypical for projects of the same general kind (e.g., a product/service development project undertaken in order to extend the firm's market into a new area).

Armed with this background, the PM should briefly study the project with an eye to preparing an invitation list for the project launch meeting. At the top of the list should be at least one representative of senior management, a strong preference given to the individual with the strongest interest in the project, the probable project champion. (The champion is usually, but not necessarily, the senior manager with responsibility for the project.) Recall in Chapter 2 we noted that the project champion could lend the political clout that is occasionally needed to overcome obstacles to cooperation from functional managers—if such obstacles were not amenable to dissolution by the PM.

Next on the invitation list come the managers from the functional areas that will be called upon to contribute competencies or capacities to the project. If highly specialized technical experts will be needed, the PM can add individuals with the required expertise to the list, after clearing the invitation with their immediate bosses, of course.

The PM may chair the launch meeting, but the senior manager introduces the project to the group, and discusses its contributions to the parent organization. If known and relevant, the project's tentative priority may be announced, as should the tentative budget estimate used in the project selection process. If the due dates for deliverables have been contracted, this should also be made clear. The purpose of senior management's presence is to ensure that the group understands the firm's commitment to the project. It is particularly important for the functional managers to understand that management is making a real commitment, not merely paying lip service.

At this point, the PM can take over the meeting and begin a group discussion of the project. It is, however, important for the senior manager(s) to remain for this discussion. The continuing presence of these august persons more or less assures cooperation from the functional units. The purpose of the discussion is to develop a general understanding of what functional inputs the project will need.

Some launch meetings are restricted to brainstorming a problem. The output of such a meeting is shown in Table 3-1. In this case, the Director of Human Resources (HR) of a medium-size firm was asked by the Board of Directors to set up a program to improve employee retention. At the time, the firm had a turnover rate slightly above 60 percent per year among its technical employees. (A turnover rate of 50 percent was about average for the industry.) The HR Director held a launch meeting of all department heads, all senior corporate officers, and members of the Board. At this meeting, the group developed a list of "action items," each of which became a project.

When dealing with a single project, it is common for a preliminary plan to be generated at the launch meeting, but we question the advisability of this. For either functional managers or the PM to guess at budgets or schedules with no real study of the project's deliverables is not prudent. First, the transition from a "tentative, wild guesstimate" made by senior managers or the EPMO to "but you promised" is instantaneous in these cases. Second, there is no foundation for mutual discussion or negotiation about different positions taken publicly and based on so little knowledge or thought. It is sufficient, in our judgment, to get a firm commitment from functional managers to study the proposed project and return for another meeting with a technically (and politically) feasible plan for their group's input to the project.

Table 3.1. Program Launch Meeting Output, Human Resources Development

It has been said, "If this means many planning meetings and extensive use of participatory decision making, then it is well worth the effort (Ford and McLaughlin, 1992, p. 316). If the emphasis is on "participative decision making," we agree. Actual planning at the launch meeting should not go beyond the most aggregated level unless the deliverables are well understood or the delivery date is cast in concrete and the organization has considerable experience with similar projects. Of course, if this is the case, a major launch meeting may not be required.

The results of the launch meeting should be that: (1) the project's scope is understood and temporarily fixed; (2) the various functional managers understand their responsibilities and have committed to develop an initial task and resource plan; and (3) any potential benefits to the organization outside the scope of the project are noted. In the meetings that follow, the project plan will become more and more detailed and firmer. When the group has developed what appears to be a workable plan with a schedule and budget that seem feasible, the plan moves through the appropriate management levels where it is approved, or altered and approved. If altered, it must be checked with those who did the planning. The planners may accept the alterations or a counterproposal may be made. The project plan may cycle up and down the managerial ladder several times before it receives final approval, at which time no further changes may be made without a formal change order (a procedure also described in the plan).

Irrespective of who alters (or suggests alterations to) the project plan during the process described above, it is imperative that everyone be kept fully informed. It is no more equitable for a senior manager to change a plan without consultation with the PM (and, hence, the project team) than it would be for the PM or the team to alter the plan without consultation and approval from senior management. If an arm's-length client is involved, the client's approval is required for any changes that will have an effect on the schedule, cost, or deliverable. Clearly, the PMO (or EPMO) can facilitate this process.

Open, honest, and frequent communication between the interested parties is critical for successful planning. What emerges from this process is sometimes called the project baseline plan. It contains all the nine elements noted in Section 3.1 and all amendments to the plan adopted as the project is carried out. As noted above, when senior management, the client, and other stakeholders have "signed-off" on the plan, it becomes a part of the Project Charter, a contract-1ike document affirming that all major parties-at-interest to the project are in agreement on the deliverables, the cost, and the schedule.

Inadequate up-front planning, especially failing to identify all important tasks, is a primary contributor to the failure of a project to achieve its cost and time objectives. Therefore, a primary purpose for developing a WBS is to ensure that any task required to produce a deliverable is not overlooked and thereby not accounted for and planned.

The previous subsection discussed the planning process as seen from the outside. The PM and the functional managers developed plans as if by magic. It is now time to be specific about how such plans may be generated. In order to develop a project plan that will take us from start to finish of a project, we need to know precisely what must be done, by whom, when, and with what resources. Every task, however small, that must be completed in order to complete the project should be listed together with any required material or human resources.

Making such a list is a nontrivial job. It requires a systematic procedure. While there are several systematic procedures that may be used, we advise a straightforward and conceptually simple way to attack the problem—the hierarchical planning process— which is how to build a Work Breakdown Structure (WBS) for the project.

To use this process, one must start with the project's objective(s). The planner, often the PM, makes a list of the major activities that must be completed to achieve the objective(s). The list may be as short as two or three activities, or as large as 20. Usually the number is between 5 and 15. We call these Level 1 activities. The planner now takes each Level 1 activity and delegates it to an individual or functional group. (The PM might delegate one or more Level 1 tasks to him- or herself.) The delegatee deals with the task as if it is itself a project and makes a plan to accomplish it; that is, he or she lists a specific set of Level 2 tasks required to complete each Level 1 task. Again, the breakdown typically runs between 5 and 15 tasks, but a few more or less does not matter. The process continues. For each Level 2 task, someone or some group is delegated responsibility to prepare an action plan of Level 3 subtasks. The procedure of successively decomposing larger tasks into their component parts continues until the lowest level subtasks are sufficiently understood so that there is no reason to continue. As a rule of thumb, the lowest level tasks in a typical project will have a duration of a few hours to a few days. If the team is quite familiar with the work, longer durations are acceptable for the lowest level tasks.

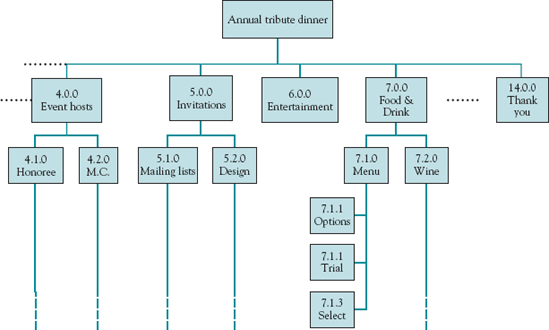

Another simple approach to creating the WBS begins by gathering the project team together and providing each member with a pad of sticky-notes. After defining the project's objectives, and Level 1 tasks, team members then write on the sticky-notes all the tasks they can think of that are required to complete the project. The sticky-notes can then be placed on the wall and arranged in various ways. One advantage of this approach is that it provides the entire team with a better understanding of the work needed to complete the project. The fact that it is a cooperative exercise also helps the project team to bond. Finally, this exercise can generate a WBS tree. Figure 3-1 illustrates the tree. A colleague called this a "Gozinto chart." (He said it was named after a famous Italian mathematician, Prof. Zepartzat Gozinto. The name has stuck.)

Microsoft Project (MSP) will make a WBS list (but not a tree-chart) at the touch of a key. The task levels are appropriately identified; for example, the WBS number "7.5.4" refers to the "Level 3, task Number 4" that is needed for "Level 2, task 5" that is a part of "Level 1, task 7." (The PM has the option of using any other identification system desired, but must enter the identifiers manually.)

Task levels are appropriately organized on the MSP printout, with Level 1 tasks to the left and others indented by level. If one uses a tree diagram and each task is represented by a box with the WBS identifier number, one can add any information one wishes—given that it will fit in the box. Such an entry might be the proper account number to charge for work done on that task, or the name of the individual (or department) with task responsibility, or with a space for the responsible party's signature denoting that the person has accepted accountability by "signing-off. " As we will see, additional information is often added by turning the "tree" into a list with columns for the additional data.

1n doing hierarchical planning, only one rule appears to be mandatory. At any given level, the "generality" or "degree of detail" of the tasks should be roughly at the same level. One should not use highly detailed tasks for Level 1 plans, and one should not add very general tasks at Level 3 or more. This can best be done by finding all Level 2 subtasks for each Level 1 task before moving one's attention to the Level 3 subtasks. Similarly, break all Level 2 tasks into their respective Level 3 tasks before considering any Level 4 subtasks, if the breakdown proceeds that far. A friend of ours who was an internationally known artist and teacher of industrial design explained why. When producing a painting or drawing, an artist first sketches-in the main compositional lines in the scene. The artist then adds detail, bit by bit, over the whole drawing, continuing this process until the work is completed. If this is done, the finished work will have "unity." Unity is not achieved if individual areas of the picture are completed in detail before moving on to other areas. A young art student then made a pen-and-ink sketch of a fellow student, showing her progress at three different stages (see Figure 3-2).

We have said that the breakdown of Level 1 tasks should be delegated to someone who will carry out the Level 2 tasks. It is the same with Level 2 tasks being delegated to someone who will design and carry out the required Level 3 tasks. A relevant question is "Who are all these delegatees?" Let's assume that the project in question is of reasonable size, neither very large nor small. Assume further that the PM and the functional managers are reasonably experienced in dealing with similar projects. In such a case, the PM would probably start by working on Level 1. Based on her background, the PM might work on Level 2 of one or more of the Level 1 tasks. Where recent experience was missing, she would delegate to the proper functional manager the task of specifying the Level 2 tasks. In the same way, the latter would delegate Level 3 task specification to the people who have the appropriate knowledge.

In general, the job of planning should be delegated to the lowest competent level. At Level 1, this is usually the PM. At lower levels, functional managers and specialists are the best planners. In Chapter 2 (Section 2.1) we described that strange bugbear, the micromanager. It is common for micromanagers to preempt the planning function from subordinates or, as an alternative, to allow the subordinate to develop an initial plan that the micromanager will amend with potentially disastrous results. The latter is an event reported with some frequency (and accuracy) in Dilbert©.

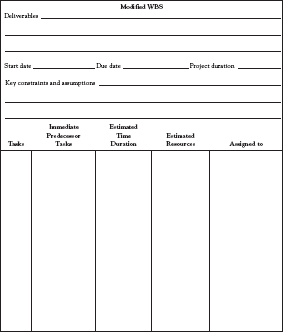

The WBS can be reshaped and buttressed with some additional data often not included in the project's WBS. The WBS is generally oriented toward the project's deliverables. The additions increase its orientation toward the planning and administration of the work. It does this by using available material, while adopting a format that is not typically used by the WBS. Figure 3-3 illustrates a layout that helps to organize the required information. We refer to these layouts as "modified" WBSs. The additional data in the columns are: (1) estimates of the resources required for each task in the plan, (2) the estimated time required to accomplish each task, (3) information about who has responsibility for the task, and (4) data that will allow tasks to be sequenced so that the set may be completed in the shortest possible time. Once the project starting date is known, item 2 in the preceding list may be changed from the time required for a subtask completion to the date on which the subtask is scheduled for completion.

To understand the importance of item 4 in the list, consider a set of subtasks, all of which must be completed to accomplish a parent task on a higher level. It is common in such a set that one or more subtasks (A) must be completed before one or more other subtasks (B) may be started. The former tasks (A) are said to be predecessors of the successor tasks (B). For instance, if our project is to paint the walls of a room, we know that before we apply paint to a wall, we must do a number of predecessor tasks. These predecessors include: clear the floor area near the wall to be painted and cover with drop cloths; remove pictures from the wall; clean loose dirt, oil, grease, stains, and the like from the wall; fill and smooth any cracks or holes in the wall; lightly sand or score the wall if it has previously been painted with a high-gloss paint; wipe with a damp cloth or sponge to remove dust from the sanding; and mask any surrounding areas where this paint is not wanted. All these tasks are predecessors to the task "Paint the walls."

The predecessor tasks for "paint the walls" have been listed in the order in which they might be done if only one person was working. If several people are available, several of these tasks might be done at the same time. Note that if three tasks can be done simultaneously, the total elapsed time required is the time needed for the longest of the three, not the sum of the three task times. This notion is critical for scheduling, so predecessors must be listed in the WBS. One convention is important. When listing predecessors, only the immediate predecessors are listed. If A precedes B and B precedes C, only B is a predecessor of C.

While Table 3-1 illustrates the output of a project launch meeting (more accurately a program launch meeting), Table 3-2 shows a WBS for one of the action items resulting from the launch meeting. With the exception of tasks 3 and 4, it is a Level 1 plan. Three Level 2 items are shown for tasks 3 and 4. Because the HR Director is quite familiar with such projects, violating the one-level-only rule is forgivable. Note also that the HR Director has delegated some of the work to himself. Note also that instead of assumptions being shown at the beginning of the WBS, project evaluation measures were listed.

The WBS not only identifies the deliverable, but also may note the start date if it is known or other information one wishes to show. Once the subtasks and their predecessors have been listed along with the estimated subtask activity times, the probable duration for the set of subtasks, and thus the task due date, can be determined as we will see in Chapter 5. If the estimates for the durations and resource requirements for accomplishing the subtasks are subject to constraints (e.g., no overtime work is allowed) or assumptions (e.g., there will be no work stoppage at our subcontractor's plant), these should be noted in the WBS.

Table 3.2. A Modified WBS for Improving Staff Orientation

A Modifi ed WBS for Improving Staff Orientation Project Objective: Enhance new employee orientation to improve retention and more effectively communicate organization's policies and procedures. Measurable Outcomes: Increase in retention rate for new hires. New hires better understand mission, vision, and core values of organization. Competency level of new hires increased. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Task | Duration | Predecessor | Resources | Assigned To |

1. Orientation task force launched 2. Compile orientation evaluations for areas of improvement | 2 weeks 4 weeks | − − | Education Manager, Education Staff (3), two Department Managers, three Staff representatives, facilitator | HR Director Education |

3. Enhancement proposal prepard

| 2 weeks 1 week 2 weeks | 1, 2 3(a) 3(b) | Orientation Task Force Education Manager Orientation Task Force | Education Manager HR Director Education Manager |

4. Orientation presentations enhanced

| 4 weeks 6 weeks 6 weeks | 3(c) 4(a) 4(a) | Speakers, Education Staff IS trainer, Education Staff, Speaker Education Staff, Speaker | Education Staff Education Staff Education Staff |

5. Review evaluation tool to measure outcomes | 2 weeks | 3 | Education Manager | Education Manager |

6. Facilitate physical changes necessary to orientation room | 4 weeks | 4 | Education Staff, AV Staff, Facilities Staff | Education Manager |

7. Implement revised orientation program | 0 days | 5, 6 | Education Staff, Speakers, HR Staff | Education Manager |

8. Evaluate feedback from first two orientation sessions | 2 months | 7 | Education Staff | Education Manager |

9. Present findings to executive team | 1 week | 8 | Education Manager | HR Director |

10. Evaluate feedback from first six orientation sessions | 6 months | 7 | Education Manager | Education Manager |

11. Develop continuous process improvement systems for feedback results | 4 weeks | 7 | Education Staff | Education Manager |

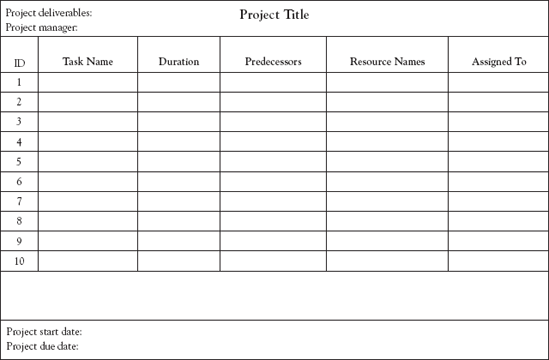

If one wishes, the information in the form shown in Figure 3-2 can be entered directly into Microsoft Project® (MSP). Alternatively, one can produce a WBS using MSP, directly, as shown in Figure 3-4. The project title can be entered in a header or footer to the form, as can other information such as a brief description of the deliverables, the name of the PM or the task manager, the project start and/or due dates, and the like.

Table 3-3 shows a WBS generated on MSP with task durations, and start and finish times for the Level 1 tasks in an infection control project. The project begins on September 12 and ends on November 30. As is customary, people work a five-day week so a three-week task has 15 work days and 21 calendar days (three weeks), assuming that the individual or team is working full-time on the task. As we will see in Chapter 5, one usually dares not make that assumption and should check carefully to determine whether or not it is a fact. If the one performing the task is working part-time, a task that requires five days of work, for example, may require several weeks of calendar time. We will revisit this problem in Chapter 5.

MSP makes the task of Level 1 planning of the broad project tasks quite straightforward. The same is true when the planners wish to generate a more detailed listing of all the steps involved in a project. The PM merely lists the overall tasks identified by the planning team as the activities required to produce the project deliverables—for example, the output of a brainstorming session. The PM and the planning team can then estimate task durations and use MSP to create a WBS. Table 3-4 shows a planning template used by a software company when they have their initial project brainstorming meetings about delivering on a customer request.

MSP has a planning wizard that guides the PM through the process of identifying all that is necessary to take an idea for a project activity and turn it into a useful WBS.

Table 3-5 is an example of a template developed by a computer systems support company. Company planners repeatedly performed the same steps when clients would ask for a local area network (LAN) installation. They treated each job as if it were a new project, because costs and resource assignments varied with each assignment. To improve efficiency, they developed a planning template using MSP. After meeting with a client, the project manager could add the agreed-upon project start date, and any constraints on the schedule required by the client. The steps to install the LAN remained the same. The start and finish dates, and the number of resources needed to meet the schedule were adjusted for each individual client, but the adjustments were usually small. Once the schedule of a specific job was decided, the PM could determine the resources needed to meet that schedule and find the cost of the project.

Table 3.3. A WBS Showing Level 1 Tasks for an Infection Control Project (MSP)

Pulmonary Patient Infection Control Project F. Nightingale, RN | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

ID | Task Name | Predecessors | Duration | Start | Finish | Resources |

1 | Form a task force to focus processes for pulmonary patients | 2 wks | 9/12 | 9/25 | Infec. Control RN, Dr., Educator | |

2 | Identify potential processes to decrease infection rate | 1 | 3 wks | 9/26 | 10/16 | Team |

3 | Develop a treatment team process | 1,2 | 3 wks | 9/26 | 10/16 | Team |

4 | Education | 3 | 1 wk | 10/17 | 10/23 | RNs, LPNs, CNAs |

5 | Implement processes on one unit as trial | 4 | 3 wks | 10/24 | 11/13 | Unit staff |

6 | Evaluate | 5 | 1 wk | 11/14 | 11/20 | Infec. Control RN |

7 | Make necessary adjustments | 6 | 1 wk | 11/21 | 11/27 | Infec. Control RN |

8 | Implement hospital-wide | 7 | 3 days | 11/28 | 11/30 | Unit staffs |

Table 3.4. Template for a Brainstorming Planning Meeting

ID | Potential Steps | Objective | Success Measure | Barriers | Notes | Contact | E-mail Address |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 | Idea1 | ||||||

2 | Idea 2 | ||||||

3 | Idea 3 | ||||||

4 | Idea 4 | ||||||

5 | Idea 5 | ||||||

6 | Idea 6 |

Table 3.5. An MSP Template for a LAN Installation Project

Template for LAN Installation Project | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

ID | Task Name | Duration | Start | Finish | Predecessors | Resource Names |

1 | 13 days | |||||

2 | Project start | 0 days | ||||

3 | Technical specifications determined | 10 days | 2 | Project Manager, System Analysts, Systems Consultant, Writers, Chief Editor, Senior Programmer, Vice President-Management Information Systems, Senior Writers, Administrative Assistant | ||

4 | Design plan developed | 3 days | 3 | Project Manager, System Analysts, Chief Editor, Vice President—Management Information Systems | ||

5 | Phase II—Preparation for installation | 22 days | ||||

6 | Equipment ordering | 2 days | 4 | Administrative Assistant | ||

7 | System prototype | 20 days | 6 | System Analysts, Systems Consultant, Programmers, Senior Programmer, Junior Programmers | ||

8 | Configuration | 10 days | 6 | System Analysts, Programmers, Tester, Senior Testers | ||

9 | Testing | 5 days | 8 | Tester, Senior Testers | ||

10 | Site analysis | 5 days | 6 | System Analysts, Programmers, Tester, Junior Programmers | ||

11 | Phase III—Installation | 13 days | ||||

12 | Site installation | 3 days | 7,8,10 | Tester, Project Manager, System Analysts, Systems Consultant, Senior Testers | ||

13 | Documentation set-up | 10 days | 12 | Writers, Chief Editor, Senior Writers | ||

14 | Phase IV—Installation follow-up | 12 days | ||||

15 | Orientation for client | 2 days | 13 | Project Manager, System Analysts, Systems Consultant, Programmers, Administrative Assistant | ||

16 | Support to client | 5 days | 12 | |||

17 | Post-installation review | 3 days | 16 | Project Manager, System Analysts, Systems Consultant, Chief Editor, Vice President-Management Information Systems | ||

18 | System acceptance | 0 days | 17,15 | |||

Creating this kind of template is simple. The software can calculate the cost of each different project which is most helpful to the project manager if cost, prices, or schedules must be negotiated. If the client wants the project to be completed earlier than scheduled, the PM can add the additional resources needed and project management software can determine the costs associated with the change.

If the PM wishes to include other information in the project's modified WBS, there is no reason not to do so. Some include a column to list the status of resource or personnel availability. Others list task start dates.

Note

The project launch meeting sets the project scope, elicits cooperation of others in the organization, demonstrates managerial commitment to the project, and initiates the project plan. The plan itself is generated through a hierarchical planning process by which parts of the plan are sequentially broken down into finer levels of detail by the individuals or groups that will implement them. The result is a WBS that lists all the tasks required to carry out the plan together with task resource requirements, durations, predecessors, and identification of the people responsible for each task.

At times, PMs seem to forget that many of the conventional forms, charts, and tables that they must fill out are intended to serve as aids, not punishments. They also forget that the forms, charts, and tables are not cast in bronze, but, like Emeril's recipes, may be changed to fit the PM's taste. In addition to the matters just covered, there is more about the WBS and two other useful aids—the Responsible-Accountable-Consult-Informed Matrix (RAC Matrix), and Mind Mapping—that merits discussion.

The process of building a WBS is meaningful. The PM and individual team members may differ on the technical approach to working on the task, the type and quantity of resources needed, or the duration for each subtask. If so, negotiation is apt to accompany the planning process. As usual, participatory management and negotiation often lead to improved project performance and better ways of meeting the project's goals. We have described the process to construct the project WBS above, but it bears repeating.

All project activities will be identified and arranged in successively finer detail, that is, by levels.

For each activity, the type and quantity of each required resource (including personnel) are identified.

For each activity, predecessors and task duration are estimated.

All project milestones are identified and located on the project schedule following their predecessor activities.

For each activity, the individual or group assigned to perform the work is identified. Acceptance of the assignment is noted by "signing-off."

In addition, we can determine several other pieces of information from the items previously listed.

If project milestones, task durations, and predecessors are combined, the result is the project master schedule. (The master schedule is illustrated in Chapter 5.) Additional time allowances for contingencies may be added, though we will later argue against this way of dealing with uncertainty.

The master schedule allows the PM to compare actual and planned task durations and resource usage at any level of activity, which is to say that the master schedule is also part of a control document, the Project Charter. The need for such comparisons dictates what information about project performance should be monitored. This gives the PM the ability to control the project and take corrective action if the project is not proceeding according to plan. (More information on project control is in Chapter 7.)

The project plan and the WBS are baseline documents for managing a project. If all of the above information is contained in a WBS, the WBS is not distinguishable from the project plan. WBSs, however, rarely contain so much information. Instead, they are typically designed for special purposes; for example, ensuring that all tasks are identified, and perhaps showing activity durations, sequencing, account numbers for charges, and due dates, or other matters of interest. They may be designed in any way that is helpful in meeting the needs of communicating their content.

Like the WBS, the RACI Matrix comes in a variety of sizes and shapes. Typically, the RACI matrix is in the form of a table with the project tasks derived from the WBS listed in the rows and departments or individuals in the columns. The value of the RACI Matrix is that it helps organize the project team by clarifying the responsibilities of the project team members. For an example of a simple RACI Matrix, see Figure 3-5.

In Figure 3-5 letters are used to indicate the nature of the responsibility link between a person and a task. Note that there must be at least one A in every row, which means that someone must be accountable for completion of each task. For example, examine the row with the task "Solicit quotations." In this case the Project Engineer is accountable for the task being carried out while the Field Manager will be responsible for actually doing the work associated with soliciting quotations. The project's Contract Administrator and the Compliance Officer/Risk Manager must be consulted about the solicitation process. The PM must be informed before documents are sent to potential vendors. Note that a particular individual or department can be assigned multiple responsibility links. For example, it is common for a person to be both accountable and responsible for a particular task. Other common combinations include consulted/ informed and accountable/informed.

Standard RACI Matrix templates are available to facilitate their development. One can use symbols or numbers as opposed to letters to refer to different responsibility relationships, and the references may be to departments, job titles, or names. Only imagination and the needs of the project and PM bound the potential variety. Likewise, additional columns can be added to the RACI Matrix to capture the due dates of tasks, actual dates completed, the status of tasks, performance metrics, and so on.

A final observation is needed on this subject. When we speak to functional managers about project management, one comment we often hear is anger about changes in the project plan without notification to the people who are supposed to conduct the tasks or supply services to the project. One quote from the head of a statistics lab in a large consulting firm is typical. The head of the lab was speaking of the manager of a consulting project for a governmental agency when he said, "I pulled three of my best people off other work to reserve them for data analysis on the XYZ Project. They sat for days waiting for the data. That jerk [the PM] knew the data would be late and never bothered to let me know. Then the *%$#@% had the gall to come in here and ask me to speed up our analysis so he could make up lost time."

Make sure to use the Inform category, not simply to report progress, but also to report changes in due dates, resource requirements, and the like.

In today's fiercely competitive environment, project teams are facing increasing pressure to achieve project performance goals while at the same time completing their projects on time and on schedule. Typically project managers and project team members rely on the "left" side or the analytical part of the brain to address the challenges. Indeed, if you are a business or engineering student, the vast majority of techniques that you have been exposed to in your studies relies on the logical and analytical left side of your brain. On the other hand, art students and design students tend to be exposed to techniques that rely more on imagination and images which utilize the creative "right" side of the brain. Importantly, many activities associated with project management can be greatly facilitated through the use of a more balanced whole-brain approach (Brown and Hyer, 2002).

One whole-brain approach that is particularly applicable to project management in general, and project planning in particular, is mind mapping. Mind mapping is essentially a visual approach that closely mirrors how the human brain records and stores information. In addition to its visual nature, another key advantage associated with mind mapping is that it helps tap the creative potential of the entire project team, which, in turn, helps increase both the quantity and quality of ideas generated. Because project team members tend to find mind mapping entertaining, it also helps generate enthusiasm, helps get buy-in from team members, and often gets quieter team members more involved in the process.

To illustrate the creation of a mind map, consider a project launched at a graduate business school to improve its part-time evening MBA program for working professionals. The mind mapping exercise is initiated by taping a large sheet of paper (e.g., 6 ft × 3 ft) on a wall. (One good source of such paper is a roll of butcher's wrapping paper. Several sheets can be taped together to create a larger area if needed.) It is recommended that the paper be oriented in landscape mode to help stimulate the team's creativity as people are used to working in portrait mode. In addition, team members should stand during the mind mapping exercise.

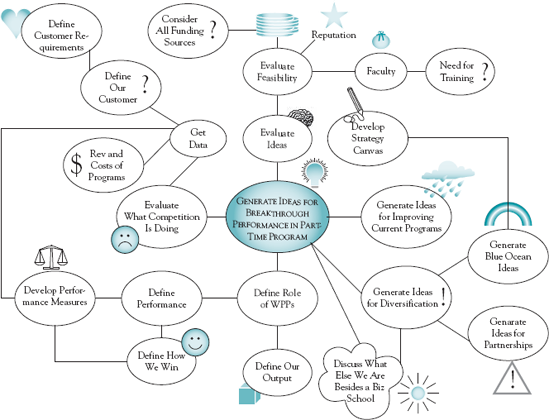

The process begins by writing the project goal in the center of the page. As is illustrated in Figure 3-6, the part-time MBA project team defined the goal for the project as generating ideas for breakthrough performance in the part-time MBA program. In particular, notice the inspirational language used in defining the project goal which helps further motivate team members and stimulate their creativity.

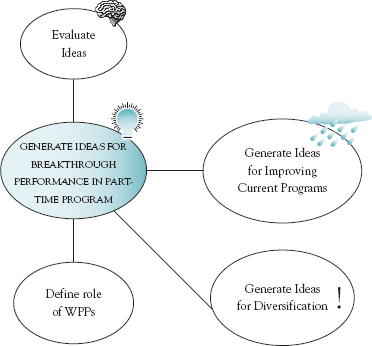

Once the project goal is defined, team members can brainstorm to identify the major tasks that must be done to accomplish this goal. In developing the mind map for the project, the MBA team initially identified four major tasks: (1) define the role of working professional programs (WPPs), (2) generate ideas for improving current programs, (3) generate ideas for diversification, and (4) evaluate the ideas generated. As illustrated in Figure 3-7, these major tasks branch off from the project goal.

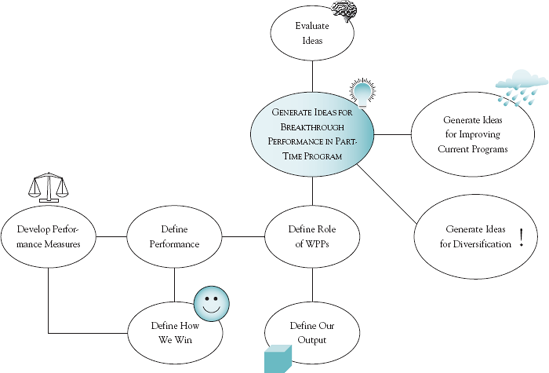

Developing the mind map proceeds in this fashion whereby components in the mind map are continuously broken down into more detailed tasks. For example, Figure 3-8 illustrates how the define role of the WPPs task was broken down into more detailed tasks. Figure 3-9 provides the final map for the MBA project.

A couple of comments regarding the process of mind mapping are in order. First, color, word size, word shape, and pictures should all be used to add emphasis. In fact, team members should be encouraged to use pictures and images in the mind map over using words. The brain processes and responds to symbols and pictures differently than it does to words. When using words, key words as opposed to full sentences should be used. Also, it should be noted that it is OK to be messy when developing the original mind map. Indeed, one should not expect the original mind map to resemble something as polished as the mind map shown in Figure 3-9. Rather, the mind map will typically need to go through several iterations of polishing and refining. It should also be noted that the polishing and refining can be greatly facilitated with the use of a computer graphics program.

In addition, multiple team members can and should contribute to the mind map simultaneously. In fact, one team member should be formally designated as the facilitator to ensure that all team members are contributing to keep team members focused on the project, and to ensure that team members are focusing on project tasks—not goals. Finally, at the most detailed level, tasks should be expressed using a noun and a verb (e.g., develop measures, generate ideas, define output).

Unfortunately, it is all too common for projects to go over budget and/or be completed late. In many cases insufficient upfront planning is the major culprit. With inadequate upfront planning, important tasks are overlooked, which in turn results in underestimating the project budget and duration. Mind mapping is a fast and effective tool that can greatly facilitate project planning and help minimize problems that result from inadequate upfront planning.

A polished and refined mind map facilitates a number of other project-related activities. For example, the mind map can be easily converted into the traditional WBS. Furthermore, the mind map can be used to facilitate risk analysis, setting project team meeting agendas, allocating resources to project activities, and developing the project schedule (see Brown and Hyer, 2002, for additional details on the use of mind mapping for project management).

Note

From the Work Breakdown Structure, one can extract a list of all tasks arranged by task level. The WBS will show numeric identifiers for each task plus other information as desired. The WBS may take a wide variety of forms. From the WBS one can also develop the RACI Matrix which details the nature of responsibility of each individual or group involved in the project to the specific tasks required to complete the project. Mind mapping can greatly enrich the planning process.

In Chapter 2 we promised further discussion of multidisciplinary teams (MTs) on projects. We will now keep that promise. We delayed consideration of MTs until we discussed planning because planning is a primary use for such teams. Using MTs (or transdisciplinary teams as they are sometimes called) raises serious problems for the PM. When used on sizable, complex projects that necessitate inputs from several different departments or groups, the process of managing the way these groups work together is called interface coordination. It is an arduous and complicated job. Coordinating the work of these groups and the timing of their interaction is called integration management. Integration management is also arduous and complicated. Above all, MTs are almost certain to operate in an environment of conflict. As we will see, however, conflict is not an unmitigated disaster.

A great deal has been written about the care and feeding of teams, and much of it has been encapsulated in a delightful short work by Patrick Lencioni (2002). He writes of the "Five Dysfunctions of a Team." They are "absence of trust," "fear of conflict," "lack of commitment," "avoidance of accountability," and "inattention to results." These dysfunctions transform a team into a collection of individuals in spite of the appearance of harmony (artificial) among the team members. We have emphasized that team members be honest in their dealings with one another, which is required for the development of intrateam trust. We would add that it is imperative that all members understand that they are mutually dependent on each other for achievement of the team's goals.

The problems of integration management are easily understood if we consider the traditional way in which products and services were designed and brought to market. The different groups involved in a product design project, for example, did not work together. They worked independently and sequentially. First, the product design group developed a design that seemed to meet the marketing group's specifications. This design was submitted to top management for approval, and possible redesign if needed. When the design was accepted, a prototype was constructed. The project was then transferred to the engineering group who tested the prototype product for quality, reliability, manufacturability, and possibly altered the design to use less expensive materials. There were certain to be changes, and all changes were submitted for management approval, at which time a new prototype was constructed and subjected to testing.

After qualifying on all tests, the project moved to the manufacturing group who proceeded to plan the actual steps required to manufacture the product in the most cost-effective way, given the machinery and equipment currently available. Again, changes were submitted for approval, often to speed up or improve the production process. If the project proceeded to the production stage, distribution channels had to be arranged, packaging designed and produced, marketing strategies developed, advertising campaigns developed, and the product shipped to the distribution centers for sale and delivery.

Conflicts between the various functional groups were legend. Each group tried to optimize its contribution, which led to nonoptimization for the system. This process worked reasonably well, if haltingly, in the past, but was extremely time consuming and expensive—conditions not tolerable in today's competitive environment.

To solve these problems, the entire project was changed from one that proceeded sequentially through each of the steps from design to sale, to one where the steps were carried out concurrently. Parallel tasking (a.k.a. concurrent engineering or simultaneous engineering) was invented as a response to the time and cost associated with the traditional method. (The word "engineering" is used here in a generic sense.) Many years before the General Motors example noted near the beginning of Chapter 2, Section 2.6, Chrysler used parallel tasking to make their PT Cruiser ready for sale in Japan four months after it was introduced in the United States. U.S. automobile manufacturers usually took about three years to modify a car or truck for the Japanese market (Autoweek, May 22, 2000, p. 9). Possibly, "PT" for parallel tasking was the source of PT for the Cruiser.

Parallel tasking has been widely used for a great diversity of projects. For example, PT was used in the design and marketing of services by a social agency; to design, manufacture, and distribute ladies' sportswear; to design, plan, and carry out a campaign for political office; to plan the maintenance schedule for a public utility; and to design and construct the space shuttle. Parallel tasking has been generally adopted as the proper way to tackle problems that are multidisciplinary in nature.

Monte Peterson, CEO of Thermos (now a subsidiary of Nippon Sanso, Inc.), formed a flexible interdisciplinary team with representatives from marketing, manufacturing, engineering, and finance to develop a new grill that would stand out in the market. The interdisciplinary approach was used primarily to reduce the time required to complete the project. For example, by including the manufacturing people in the design process from the beginning, the team avoided some costly mistakes later on. Initially, for instance, the designers opted for tapered legs on the grill. However, after manufacturing explained at an early meeting that tapered legs would have to be custom made, the design engineers changed the design to straight legs. Under the previous system, manufacturing would not have known about the problem with the tapered legs until the design was completed. The output of this project was a revolutionary electric grill that used a new technology to give food a barbecued taste. The grill won four design awards in its first year.

The word "engineering" is used in its broadest sense, that is, the art of making practical application of science. Precisely which sciences is not specified. If the team members are problem oriented, parallel tasking works very well. Some interesting research has shown that when problem-oriented people with different backgrounds enter conflicts about how to deal with a problem, they often produce very creative solutions— and without damage to project quality, cost, or schedule (Hauptman and Hirji, 1996, p. 161). The group itself typically resolves the conflicts arising in such cases when they recognize that they have solved the problem. For some highly effective teams, conflict becomes a favored style of problem solving (Lencioni, 2002).

When team members are both argumentative and oriented to their own discipline, parallel tasking appears to be no improvement on any other method of problem solving. The PM will have to use negotiation, persuasion, and conflict resolution skills, but there is no guarantee that these will be successful. Even when intragroup conflict is not a serious issue with discipline-oriented team members, they often adopt subopti-mization as the preferred approach to problem solving. They argue that experts should be allowed to exercise their specialties without interference from those who lack expertise.

The use of MTs in product development and planning is not without its difficulties. Successfully involving transfunctional teams in project planning requires that some structure be imposed on the planning process. The most common structure is simply to define the group's responsibility as being the development of a plan to accomplish whatever is established as the project objective. There is considerable evidence, however, that this will not prevent conflict on complex projects.

One of the PM's more difficult problems when working with MTs is coordinating the work of different functional groups interacting as team members. The team members come from different functional areas and often are not used to dealing with one another directly. For the most part, they have no established dependencies on each other and being co-members of a team is not sufficient to cause them to associate—unless the team has a mission that makes it important for the members to develop relationships.

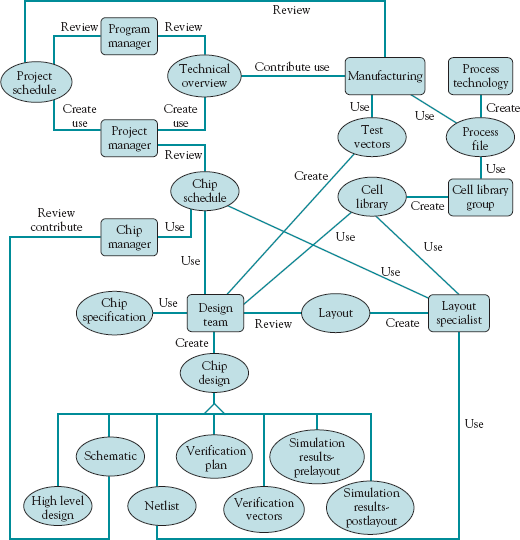

One approach to the problem of interface coordination is to expose the structure of the work assigned to the team (Bailetti, Callahan, and DiPietro, 1994). One can identify and map the interdependencies between various members of the project team. Clearly, the way in which team members interact will differ during different phases of the project's work, so each major phase must be mapped separately. Figure 3-10 shows the mapping for the design of a silicon chip.

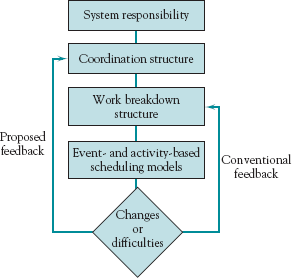

The logic of this approach to structuring MTs is reasonable. The original project plans and charts are a good initial source of information on interfaces, but project plans change during the execution of a large, complex project. Further, project plans assume, implicitly, that interfaces somehow change automatically during the different project phases—an assumption generally contrary to fact. This does not ignore the value of standard project planning and control tools of long-standing use; it simply uses interface maps to develop the coordination required to manage the interdependencies. The fundamental structure of this approach to interface management is shown in Figure 3-11.

Figure 3.10. An interface mapping of a silicon chip design project (Bailetti, Callahan, and DiPietro, 1994).

No approach to interface coordination and management, taken alone, is sufficient. Mapping interfaces does not tell the PM what to do. The maps do, however, indicate which interfaces have a high potential for trouble. As usual, populating the project team with problem-oriented people will help. If a team member is strongly oriented toward making the project a success, rather than optimizing his or her individual contribution, it will be relatively easy for the PM to identify troublesome interfaces between members of the project team.

One observation that can be made regarding integration management and parallel tasking is that both are fundamentally concerned with coordinating the flow of information. Furthermore, while the need to coordinate the flow of information is a challenge that confronts virtually all projects, the use of MTs tends to magnify this challenge. This is particularly true for new product development projects.

Compounding this problem is the fact that traditional project management planning tools such as Gantt charts and precedence diagrams (both discussed in Chapter 5) were developed primarily to coordinate the execution of tasks. This is because these tools were originally developed to help manage large but relatively well structured projects such as construction projects and ship building. However, in some cases such as new product development projects, the issue of information flows can be as important as the sequencing of tasks. In essence, traditional project management planning tools help identify which tasks have to be completed in order for other tasks to be started. Often, however, a more important issue is what information is needed from other tasks to complete a specific task?

Figure 3.11. A coordination structure model for project management (Bailetti, Callahan, and DiPietro, 1994).

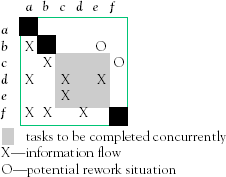

To address the issue of information flows, Steven Eppinger (2001), a professor at MIT's Sloan School of Management, proposes the development and use of a Design Structure Matrix (DSM). The first step in developing a DSM is to identify all the project's tasks and list them in the order in which they are typically carried out. This list of tasks makes up both the rows and columns of the DSM. Next, moving across one row at a time, all tasks that supply information to the task being evaluated are noted. When the DSM is completed, all the tasks that provide information that is needed to complete a given task can be determined by looking across that particular task's row. Likewise, moving down a particular task's column shows all the other tasks that depend on it for information.

An example DSM corresponding to a project with six activities is shown in Table 3-6. According to the table, completing activity c requires the gathering of information from activities b and f. Furthermore, the table indicates that activities c and f both depend on information from activity b.

As the example illustrates, a key benefit of constructing a DSM is the ability to quickly identify and better understand how information is needed. It can also highlight potential information flow problems even before the project is started. For example, all the X's above the diagonal in Table 3-6 are related to situations where information obtained from a subsequent task might require the rework of an earlier completed task. To illustrate, in the second row we observe that activity b requires information from activity e. Since activity e is completed after activity b, activity b may need to be revisited and reworked depending on what is learned after completing activity e.

The DSM also helps evaluate how well the need to coordinate information flows has been anticipated in the project's planning stage. To make this assessment, a shaded box is added to the DSM around all tasks that are planned to be executed concurrently. For example, the DSM would appear as shown in Table 3-7 if it had been planned that tasks c, d, and e were to be done concurrently. Also notice that in Table 3-7 any remaining entries above the diagonal of the matrix are highlighted as potential rework by replacing each X with an O.

In examining Table 3-7 there are two potential rework situations. Fortunately, there are a couple of actions that can be taken to minimize or even eliminate potential rework situations. One option is to investigate whether the sequence of the project activities can be changed so that the potential rework situations are moved below the diagonal. Another option is to investigate ways to complete additional activities concurrently. This latter option is a bit more complex and may necessitate changing the physical location of where the tasks are completed.

The use of a participatory management style has been, and will continue to be, emphasized in this book. In recent years several programs have been developed to institutionalize the participative style. Among these programs are Employee Involvement (EI), Six Sigma (SS), Quality Circles (QC), Total Quality Management (TQM), Self-Directed Work Teams (SDWT) [a.k.a. Self-Directed Teams (SDT) by dropping the word "work," which is what SDTs sometimes do], and Self-Managed Teams (SMT). While these programs differ somewhat in structure and in the degree to which authority is delegated to the team, they are all intended to empower workers to use their knowledge and creativity to improve products, services, and production processes.

There is no doubt that some of these teams meet their goals, and there is also no doubt that many of them do not. Research on the effectiveness of these programs yields mixed results (Bailey, 1998). The research (and our experience supports this) leads to the tentative conclusion that the success or failure of empowerment teams probably has more to do with the way in which the team program is implemented than with the team itself. When empowerment team programs are implemented with a well-designed plan for involvement in solving actual problems, and when the teams have full access to all relevant information plus full support from senior management, the results seem to be quite good. When those conditions are not present, the results are mediocre at best.

Some of the more important advantages of empowerment are:

All of these advantages are strong motivators for team members. If the team is self-directed, however, an additional element must be present for the team to have a reasonable chance at success. Senior management needs to spell out the project's goals and to be quite clear about the range of authority and responsibility of the team. "Self-directed" does not mean "without direction"—nor does it apply to the team's mission. Furthermore, taking an active role in the team's work is not "voluntary" for team members. There must be a well-publicized way of "deselecting" team members who do not actively participate and do not carry a fair share of the team's workload.

The rapid growth of virtual projects employing team members from different countries, industries, and cultures raises additional problems for empowering work teams. Customary worker/boss relationships and interactions vary widely across industrial and cultural boundaries. In such cases, the potential PM needs some training plus experience with the different cultures before taking full responsibility for empowering and leading globalized multidisciplinary teams.

For MTs and parallel tasking to be successful, whether or not the teams are self-directed, the proper infrastructure must be in place, proper guidance must be given to the teams, and a reward structure that recognizes high-quality performance should be in place.

All of the potential problems that MT and parallel tasking can suffer notwithstanding, teams are extraordinarily valuable during the process of planning a project. They are certainly worth the effort of managing and coordinating.

Note

The task of managing the ways in which different groups interact during planning and implementation of projects is called "interface coordination." An important aid to interface coordination is mapping the interactions of the various groups. The task of integrating the work of these groups is called integration management. Parallel tasking allows all groups involved in designing a project to work as a single group and join together to solve design problems simultaneously rather than separately and solving the problems sequentially. When information from some project activities is required to complete other activities, the Design Structure Matrix may be quite useful.

In the next chapter, we use the project plan to develop a project budget. We discuss conflict surrounding the budgetary process. Then we deal with uncertainty, the project's (and PM's) constant companion.

What are some of the benefits of setting up a project plan for routine, frequent projects?

Discuss the reasons for inviting the functional managers to a project launch meeting rather than their subordinates who may actually be doing the work.

Discuss the pros and cons of identifying and including the project team at the project launch meeting.

Why do so many "self-directed teams" perform poorly? What can be done to improve their performance?

Why is participatory management beneficial to project planning? How does the process of participatory management actually work in planning?

What is the difference between the Resource column on the WBS (that would include personnel needed by the project) and the Assigned To column?

Under what circumstances is it sensible to do without a project launch meeting?

What limitation associated with traditional project management techniques like Gantt charts and precedence diagrams does the Design Matrix Structure overcome?

9. For each one of the nine components of a project plan, discuss the problems that might be raised if the element was incomplete.

10. Give several examples of a type of project that would benefit from a template project action plan being developed.

11. Why is the hierarchical planning process useful for project planning? How might it influence the plan if the hierarchical planning process was not used?

12. What causes so much conflict on multidisciplinary teams? As a PM, what would you try to do to prevent or reduce such conflict?

13. Of what help is a "map of interdependencies" to a PM who is managing a transdisciplinary team?