CHAPTER 3

Levels of Measurement

Far too often, measurement fails because of a “one size fits all” approach. At least three measurement programs must be in place for measurement to succeed: an executive or strategic level, a management or tactical level, and a task or technical level. It is important to remember that the purpose of measurement is to inform. Informed decisions enable some type of action to be taken; what is not quite as obvious but equally essential is that measurement can beneficially support the decision not to act. For measurement to fulfill this role, it must be focused at the level at which the decision is made or where the assurance that no action is needed lies.

One way to characterize the different measurement programs is to consider the decision support in a time perspective. Most executive decisions affect the relatively distant future. Decisions must be made, for example, about a two-, five-, or ten-year plan. Long-range forecasts, next year’s budgets, and multiyear projects fill the executive’s decision agenda. Contrast this with the line manager’s short-term focus on the current quarter’s budget or this month’s performance, or a worker’s attention to the current task.

EXECUTIVE MEASUREMENT PROGRAM

Who has not heard something to the effect of “just give me the bottom line”? Most often, the request comes from upper management or someone with aspirations of upper management. The “big picture” is a concept echoed throughout boardrooms and offices continually.

Considering the perspective of the properties of measurement, what implications would apply to executive metrics in terms of their validity, accuracy, and precision? Validity is a binary property of measures: they are either valid or not. A good example is the tenuous relationships of all of the parameters in weather forecasting models. As long as the ocean surface temperature and temperature patterns remain close to their values when all the forecasting models were made, certain parameters such as air pressure gradients are valid predictors of near-term weather. Too often, the term “accurate” is used when what is meant is “valid.” When the ocean temperatures changed due to El Niño, many of the parameters that drive the forecast models were no longer valid, and the forecasts were incorrect. Yet validity is still expressed as a confidence interval where there is a certain percentage of confidence that the measure lies within a certain range or has a certain relationship to the inferences that are relying on the measure. Although there are no rules, most executives are uncomfortable if the confidence interval expressed as a percentage is below about 70 percent.

Accuracy is another consideration that contrasts the executive measurement program with the others. One description that is often used when discussing far too much measurement effort is: “Measure it with a micrometer, mark it with a grease pencil, and cut it with an ax.” It is funny until one really considers what these micrometers and their use cost. People are usually uncomfortable dealing with imprecise numbers. A schedule to the nearest day may give a greater sense of comfort than one to the nearest month. However, the effort needed to produce the more detailed estimate may be considerably more than the effort needed to produce a general estimate even though a general estimate would satisfy the need for a schedule estimate at the time it is taken.

Translate that into a cost of accuracy and it is obvious why measurement activity fails for cost reasons. The nearest calendar quarter for time measures, or the nearest hundred dollars for cost measures, for example, are typically at the level of accuracy needed to support executive decisions. It is also important to note that any metric is only as accurate as the least accurate measure from which it is developed, no matter how precisely it is stated.

Precision, the level of detail of the metric, also needs to be consistent with accuracy. To say that a project will be complete on Friday at noon two years from today, plus or minus three months, may sound silly; however, far too often, precise measures are given to the nearest month that have an accuracy to the nearest quarter or to the dollar or nearest hundred dollar precision with an accuracy to the nearest ten thousand dollars.

Measurement malpractice, notwithstanding outright fraud, usually lies in problems with the validity, accuracy, and precision of the measures and metrics used to support decisions.

Another key observation about the executive measurement program is that virtually none of the measures or metrics directly originates from or is constructed at the executive level. The measures come from lower levels in the organization; in “rolling up” to the executive level, metrics are aggregated among the several activities and organizational units that contribute to the overall operation of the organization.

MANAGEMENT MEASUREMENT PROGRAM

For our purposes, the management measurement program is the most important. Project managers, department managers, and process or functional managers must all make informed decisions that have an immediate or near-immediate and direct impact on the performance of the part of the organization for which they are responsible. These decisions usually also have at least an indirect impact on other parts of the organization. Compared to executive measures, most managers deal with a time frame that is limited to the present and the immediate or near future.

The accuracy of management measures generally needs to be greater than the accuracy of executive measures. The independence of measures and metrics is higher for managers than for executives. For example, a headcount growth measurement will also impact specific office space and equipment considerations. At lower levels of detail such as at the management level, if a program must be completed in two years, certain things within some departments or projects must be done now or in the very near future.

At the managerial level, for example, payments are made, bills are cut, and taxes are calculated, all of which must be precise to the nearest penny (or appropriate lowest unit of currency). Even where lower levels of precision are acceptable, in general, the managerial level measures need to be at a much higher level of precision than do most executive measures. Many measures are comparisons, such as actual to budget. At executive levels, where many individual budgets are precise to the nearest thousand dollars as they are rolled up to include many budgets for executive decision support, the precision also is reduced to reflect the cumulative effect of the combined uncertainty and the level at which the executives make their decisions.

To illustrate the concept simply, consider if there were 10 department budgets of $10 million each and accurate to 10 percent (or plus or minus $10,000). Therefore, expressing these budgets to anything more precise than the nearest $10,000 dollars is inappropriate. When all these budgets are rolled up, there is $100 million in the total and a combined inaccuracy of plus or minus $100,000. It is still plus or minus 10 percent accuracy, but the precision is now to the nearest $100,000.

TACTICAL MEASUREMENT PROGRAM

The lowest level of the measurement program is at the tactical level. This level will have the highest variability, since it supports the actual performance of tasks and the execution of processes. People and equipment operating at this level usually need a lot of information to ensure that the right tasks are carried out and that they are performed correctly. At this level, the source of the measures, the construction of the metrics, and the communication of the results are all at the same level. These measures can be very effective without much formality.

An important reason to have a good measurement program is the information available concerning any data item before it is reported. If the reported data are inconsistent with the expectation, then the data should be investigated. Most often the first things checked and the most common causes of discrepancies are errors in the data. Once the data have been checked and determined to be correct, if a discrepancy between the expectation and the value still exists, then an investigation is warranted.

One of the primary purposes of a measurement program is to effectively allocate the scarce resources available to fix problems by ensuring that a problem gets fixed at its source. Another key advantage of good measurement is the ability to distinguish the need to fix a problem from a need to fix the process.

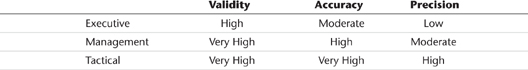

Table 3-1 compares the validity, accuracy, and precision requirements for each of the three general measurement programs. It is worthwhile to note that high validity is very important at all levels. Invalid measures support invalid decisions. Slang for the wrong precision is “gnat’s eyebrow” or “picky;” slang for low accuracy is “close enough;” while invalidity is usually referred to as “apples and oranges.” So make sure your measurements are “in the right church” (valid), “in the right pew” (accurate), and you are “in the right seat,” “singing the right hymn,” and “on key” (precise). As we will see in Chapter 4, treating measurement as a service by identifying the right customers and incorporating their requirements ensures that all three levels are appropriately covered.

TABLE 3-1 Requirements for Measurement Programs![]()

![]()