CHAPTER |

4 |

Destiny is no matter of chance. It is a matter of choice. It is not a thing to be waited for; it is a thing to be achieved.

—William Jennings Bryan

Building Relationships

Sponsors expect project managers to achieve results. Project managers expect upper manager support. Clients expect value added from service providers. Providers need to be seen as leaders in front of customers. You have to know the value systems of executives in the client organization if you want to impress them. A wise approach is always to “seek first to understand.” Find out what their goals are. Find out their communication style. Find out what issues or problems they are dealing with, and help them find solutions. Expectations are rampant in every field of endeavor. How we uncover and fulfill them is key to ongoing success.

Sometimes you can help executives get promoted, and this situation makes room for you to move forward. Let them know you need their help throughout the project life cycle. Help client sponsors get what they want and help them look good to their bosses, and reap the benefits of repeat business. Help others, and they will keep you as they move forward.

Taking into account that client expectations will change because clients are, after all, human beings, how can you discover what they want? At any given moment, they probably know what they know and what they don't know about their project requirements.

This chapter covers relationship building within the context of project sponsorship. A suggested mindset is that all relationships are important. It takes concerted, extra efforts on the part of all persons to create and maintain effective relationships. Seek out motivating factors that guide stakeholder behaviors.

We provide general advice on gaining credibility, working through hidden agendas, and dealing with difficult people. This advice is applicable to all relationships.

We also cover special situations when providers do work for clients. The terms customer and client are used almost interchangeably. Client relationships tend to be more intensive because clients usually request that a project be done for them, whereas customers may simply purchase the outcome from the project. We describe ways to improve relationships between provider sponsors and client sponsors by focusing on communication.

Motivation

Daniel Pink (2009) provides a description of Motivation 3.0—a paradigm shift that is highly relevant to our discussion for building relationships among high-performing professionals. Here are three elements from Pink's Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us that sponsors as well as all project leaders are wise to incorporate into daily operations:

Autonomy. People want autonomy over task (what they do), time (when they do it), team (who they do it with), and technique (how they do it). Companies that offer autonomy, sometimes in radical doses, are outperforming their competitors.

Mastery. Engagement produces mastery—becoming better at something that matters. The pursuit of mastery is an important but often dormant part of our drive and is essential to making one's way in the economy.

Purpose. Humans seek purpose—a cause greater and more enduring than themselves. Purpose maximization (alongside profit maximization) has the potential to rejuvenate businesses and remake our world.

To aid in understanding executive motivation, Target Training International (Coles, 2011) reports on business theory that indicates senior executives are driven by six key values and motivators:

- Utilitarian/economic: the primary motivation driver is money

- Theoretical: top motivators are theoretical values and a drive for learning and knowledge

- Social/altruistic: motivated by altruism and a drive to be helpful to others

- Individualistic/political: driven by power, and therefore has a desire for business success

- Traditional/regulatory: primarily driven by a desire for order

- Aesthetic: driven by form and harmony

An interesting aspect of these drivers is that they generally relate to higher-level motivating factors, similar to self-actualization found at the top in Maslow's hierarchy pyramid. Keep these motivators in mind when needing to influence executives.

Gaining Credibility

People need time to build good relationships. Credibility is normally the result of applying authenticity and integrity in a relationship. Sometimes the provider sponsor concentrates on taking care of the project budget and forgets to focus on other aspects, including what is best for project success. At other times, the client sponsor tries to take advantage by setting up a win-lose relationship. That situation is also bad for project success.

In our opinion, credibility requires being able to establish a trust relationship in which the outcome is always win-win. Client sponsor credibility is like a building—it must be built brick by brick, and the mortar needs time to dry before building higher.

Not many organizations have a formal project management selection process in place. But all companies want to have the best project managers ready for managing projects successfully. Managers expect good project results, and team members want to have the best project managers to manage successful projects—good leaders that they will follow. Managers need to cultivate not only hard but also soft skills to be successful. Most soft skills are linked to people's attitudes and behaviors.

Organizations need project managers who are honest, competent, and inspirational. For example, I (Bucero) was involved in a project whose objective was to move one organization from functional to project-oriented organization. I encountered a lot of resistance in the client organization and only a few believers. I tried to act honestly with everyone, and in many meetings, I said, “This change is difficult but not impossible.” My principle is always that today is a good day. Everything can be changed in the project environment. I applied a disciplined process and always did what I promised to do. I agreed with my client to present a project status report every Friday at 10:00 a.m., and I did. I planned to meet somebody at a determined date, and I did. Credibility is built through a succession of little details that accumulate over the course of a project. Everyone must learn from the results and refine subsequent actions. This gives credibility. Credibility and reputation are linked.

Credibility can be defined as the behavioral evidence the participants would use to judge whether or not the project leader was believable. People commonly report that such leaders “do what they say they will do,” “practice what they preach,” and “walk the walk and talk the talk” (see Englund, 2000). Credibility is something that is earned over time. It does not come automatically with the job or the title. It begins early in our lives and careers.

A credibility foundation is built step by step along a professional career path. As each step is achieved, the foundation of the future is gradually built. Team members do not want to follow a manager who is not credible, who does not truly believe in what he or she is doing and how he or she is doing it.

A manager's credibility has a significant positive outcome on individual and organizational performance. Real leaders strengthen the people around them and make others feel more important. Leaders also act as facilitators. The most important thing is the project, not the project sponsor or the project manager.

Credibility is mostly about consistency between words and deeds. Project stakeholders listen to the words and look at the deeds. Executive sponsors are expected to do what they say. They are expected to keep their promises and follow through on their commitments. But what they say must also be what team members believe. To take people to places they have never been before (as in achieving project results), project leaders and team need to be on the same path. To get people to join the voyage of discovery voluntarily requires that the aims and aspirations of leaders and teams be harmonious.

Thinking “I” instead of “we” has generated many problems for project managers and executives. Their actions run the risk of being perceived as consistent only with their own wishes, not with those of the people they are supposed to lead. When managers resort to the use of power and position, to compliance and command to get things done, they are not leading; they are dictating.

The credible leader learns how to discover and communicate shared values and visions that can form a common ground on which all can stand. Credible leaders find harmony among the diverse interests, points of view, and beliefs of the team. Standing on a strong, unified foundation, project leaders and teams can act consistently with spirit and drive to build viable projects.

Boosting Credibility

Three closely linked aspects combine to boost credibility: sharpness, harmony, and passion. Commitment to credibility begins with sharpness—clarifying the leader's commitment, needs, interests, values, vision, and project objectives.

To build a powerful and viable project, a project team needs to be in harmony about a common cause, united on where the team is going, why it is headed in that direction, and which principles will guide its actions.

Credible leaders need the ability to build a shared vision and values. Harmony exists when team members widely share, support, and endorse the intent of the commonly understood set of aims and aspirations. Not only do team members know what these are, but they are also in agreement that the shared vision and values are important to the future success of the project and the organization. They have a common interpretation of how the values will be put into practice.

Understanding and agreeing to aims and aspirations are essential to the process of strengthening credibility. But actions speak louder than words, so people who feel strongly about the worth of values will act on them. Passion is evident when principles are taken seriously: when they reflect deep feelings, standards, and emotional bonds, and when they are the basis of critical organizational resource allocations. When values are intensely felt, there is greater consistency between words and actions, and there is an almost moral dimension to “keeping the faith.”

Sharpness, harmony, and passion provide a useful framework for looking at the process of strengthening credibility. But what about the project manager's daily actions? When asking project leaders to provide specific examples of what their most admired leaders do to gain respect, trust, and a willingness to be influenced, the most frequently mentioned behaviors are that the leader “supported me,” “challenged me,” “listened to me,” “celebrated good work,” “trusted me,” “empowered others,” “shared the project vision,” “admitted mistakes,” “advised others,” “taught well,” and “was patient.” These are desired universal traits that cross all borders.

All these comments focus on serving others and making others feel important, not about making the project manager or sponsor look important. They are about empowering others, not about grabbing power. Project managers must be consistent and work hard—that is the preferred way to overcome project obstacles. Maintaining credibility requires passion, persistence, and patience, especially in the face of adversity. Often the lessons are learned the hard way, and admired leaders are ones who admit mistakes and learn from their experiences.

Practicing Credibility

Experts James Kouzes and Barry Posner (2011) identify six practices that they call the six “disciplines of credibility.” These practices, which can be adapted for use by sponsors and other project leaders, are as follows:

- Explore yourself. Explore your inner territory. For example, look into the mirror and ask yourself questions such as “Who am I?” “What do I believe in?” and “What do I stand for?” To be credible as an executive, clarify your own values and beliefs. Once you are clear on your own values, translate them into a set of guiding principles and communicate them to the team you want to lead.

- Be sensitive with team members. Understand that your own leadership philosophy is only the beginning. Being a leader requires developing a deep understanding of the values and desires of team members. Listen to them. Leadership is a relationship, and you will only be able to build that relationship on mutual understanding and respect. Team members come to believe in their leaders—to see them as worthy of their trust—when they believe that the leaders have the team's best interests at heart.

- Confirm shared values. Credible leaders honor the diversity of team members. They also find a common ground for agreement on which everyone can stand. They bring people together and join them in a cause. Project sponsors show others how everyone's individual values and interests can be served by coming to consensus on a set of common values. Confirm a core of shared values passionately, and speak enthusiastically on behalf of the project.

- Develop capacity. It is essential for project sponsors to continuously develop the capacity of their members to keep their commitments. Ensure that educational opportunities exist for individuals to build their knowledge and skills.

- Serve a purpose. Leadership is a service. Project sponsors serve a purpose for their people who have made it possible for them to lead their teams.

- Sustain hope. Credible leaders keep hope alive. Teams need a positive attitude from their leaders in troubling times of transition. Optimists are proactive and behave in ways that promote health and combat illness. People with high hope are also high achievers.

Project team members expect their leaders to have the courage of their convictions. They expect them to stand up for their beliefs. If leaders are not clear about what they believe in, they are much more likely to change positions with every fad or opinion poll. Without core beliefs and with only shifting positions, would-be leaders will be judged as inconsistent and be derided for being “political” in their behavior.

Managers expect project managers to lead successful projects and achieve good results. Credibility is a condition for project success that must be earned day-by-day throughout every project.

Hidden Agendas

The project manager needs the sponsor and vice versa. Thus, they need to collaborate for project success to benefit both the project and the organization. The sponsor and project manager need to coordinate their agendas. We cannot forget that on some occasions, priority number one for the executive assigned as a sponsor is not the project they are sponsoring but operational tasks and issues in the organization. In our experience, what happens is that some sponsors have hidden agendas.

The biggest challenge with hidden agendas is the fact that they are hidden. While a person may project an appearance of having an “open door,” in reality the “door” is closed on certain issues or topics. If these issues or topics were not hidden, we would not have issues with them. Just imagine how much easier it would be if your agenda and your sponsor's agenda were transparent. It would be clear to you what his or her intentions are; and it would be clear to your sponsor what your intentions are. No doubts whatsoever!

The relationship needed between the project manager and the sponsor is a partnership, and, like any other type of collaboration, needs trust to be successful. We believe that we have no control over whether or not people will trust us. However, we do control how trustworthy we are. Hidden agendas are partnership killers; the trust in an alliance is killed the moment a hidden agenda becomes apparent or the moment you feel your sponsor has one. You will always doubt what the other one really means and you will never completely trust your sponsor and vice versa.

Our recommendation is to be transparent in your intentions for the partnership and avoid hidden agendas. If you ever suspect your sponsor has a hidden agenda, try to get things clear by asking questions to discover the true meaning behind his or her intentions. This will not be an easy task, but it will be an essential element in building and maintaining a healthy partnership and increased possibilities for successful projects.

Questionnaire

We have created a questionnaire that you could use with your sponsor if he or she appears to have a hidden agenda:

- Will you have at least one hour for me, on a weekly basis, to talk about this project?

- Will you have half a day every 15 days to attend to the project steering committee meeting?

- Is this project a first business priority for you?

- Do you understand the importance of this project?

- Do you feel supported by the board of directors for this particular project?

- Are you sponsoring another project now or in the near future?

- Do you feel work overloaded?

- Will you travel frequently?

- What is your availability for the next 15 days to be dedicated to this project?

- Do you want to be the sponsor for this project?

Dealing with Jerks

Stanford professor Robert Sutton (2007) describes his journey that prompted a very helpful guide to dealing with difficult colleagues: “When I encounter a mean-spirited person, the first thing I think is: ‘Wow, what an asshole!’…You might call such people bullies, creeps, jerks, weasel, tormentors, tyrants, serial slammers, despots or unconstrained egomaniacs, but for me at least, asshole best captures the fear and loathing that I have for these nasty people” (p. 1).

Dr. Sutton goes on to say that his book The No Asshole Rule “shows how to keep these jerks out of your workplace, how to reform those you are stuck with, how to expel those who can't or won't change their ways, and how to best limit the destruction that these demeaning creeps cause” (p. 1). Look for small wins to sustain confidence and a sense of control, consider indifference and emotional detachment, limit your exposure, call their bluff, and seek supportive colleagues are a few ideas. As we have little to offer beyond his very descriptive words and suggestions, other than to validate that difficult people are out there, we highly recommend this reference as a means to “have long and happy lives that are free from entanglements with assholes” (p. 197).

Creating and Maintaining the Relationship

When a project starts, one question that comes to mind is: What does the client want from us as professionals and as an organization? In other words, what does the client expect from us as a result of the project?

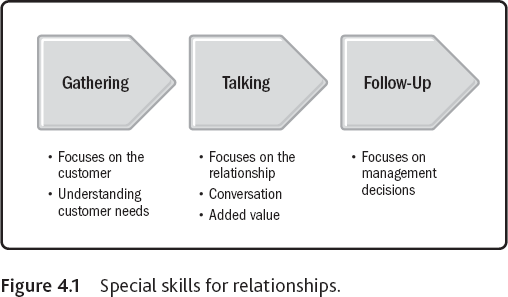

The role played by project sponsors in customer relations depends on the type of client and organization. Usually, clients want to be informed regularly about project status. They want an open path of communication between sponsors. Speaking the truth from project initiation onward is one key for project success. The provider sponsor and the client sponsor need to be open and transparent, creating the right environment for project success. A relationship with a client is a process of human interaction but also a work in progress. It involves much more than just an exchange of money and services. Most client relationships are based on conversations. The project sponsor starts the client relationship through conversations so that he or she can make the necessary management decisions and take appropriate actions during the project life cycle. Creating and maintaining that relationship requires special skills in information gathering, talking, and follow-up (see Figure 4.1).

Information gathering focuses on the customer. It is intended to help learn more about the client, the environment, and behavior patterns or customer reactions during the project life cycle. Understanding what is urgent from the client's perspective is the basis for recognizing and understanding customer needs.

Talking focuses on the relationship. It is intended to ensure that value is created in every conversation with the client. The client expects to get some value from the provider because that is what the client is paying for. The provider needs to be proactive in dealing with facts, anticipating needs, and taking advantage of prior experiences and knowledge.

Follow-up focuses on management decisions that need to be made concerning organizational and management mechanisms that enable continued information gathering and talking. Provider and client sponsors need to meet periodically on their own, not just in project steering committee meetings.

Information gathering, talking, and follow-up are not just a “to do” list for sponsors. They are not a sequence of tasks or steps. Rather, they are separate sponsor-focused, day-to-day preoccupations that create good sponsor relationships.

The following are suggested questions for information gathering, talking, and follow-up.

Information Gathering

Who is my customer? Who is the customer's customer?

What are the client's personal and professional expectations?

What is our value as perceived by the client?

Talking

What type of relationship do I want to build with my client?

How do we foster exchange?

How do we work together and share control?

What unique control mechanism ensures we are on track?

Follow-Up

Who are we?

How should I organize to move value closer to the client?

How do we measure and manage our performance?

How do we increase our capacity for change?

By asking these types of questions, sponsors will be able to guide the evolution of relationships with their clients.

On one project I (Bucero) managed, the client was unhappy with the attitude and actions of the assigned project sponsor. The project was two-and-a-half years long and involved about 150 people on the project team. The project sponsor from the service provider attended all steering committee meetings every month and actively participated during the preliminary sales phase. But he was not actively involved in contract negotiations, and he visited the client only once a month, on the day of the steering committee meeting. Sometimes I felt he delegated too many things to me as project manager. It was very difficult for him to understand the pressure I endured during the project life cycle because he was not present on site every day.

Many times I needed to make a decision because I did not have access to my sponsor (provider sponsor). I was not the right person to make some decisions, but I had to do it. The client recognized that the project lacked adequate sponsorship from the provider, but he also recognized my effort as a project manager to move the project forward. Ramifications of that recognition were that I was invited to the client executive committee to report on project status. The client wanted me attending that meeting instead of my sponsor. Little by little, I gained customer credibility. At the end of the project, the client sent a complaint letter saying that the project had no provider sponsor but the project manager was able to work very successfully with the provider project manager.

I (Englund) had the privilege of talking with Mary Michelle Scott, president of Fishbowl, a leading provider of software for inventory management and asset tracking solutions. She played a key role in a successful company buyback that honored a commitment to build an employee-owned organization, bring a strong community focus, and build the organization from a grassroots start-up to a world-class software provider. She regularly talks about traits needed to create and sustain a successful business and soar as a leader.

On the question of relationships between leaders and followers, Ms. Scott said, “You need to trust each other, open doors, forgive, and get out of the way.” She credits mentors who demonstrated these traits. We can learn from others and inculcate worthy traits into our own belief systems and daily actions.

Theodore Roosevelt said, “The most important single ingredient in the formula of success is knowing how to get along with people” (SJW, 2012). Team members don't care how much you know until they know how much you care. The ability to work with people and develop relationships is crucial to effective leadership.

What can a sponsor do to manage and cultivate good relationships as a leader? Here are a few suggestions:

- Understand people. Many times we are not listening to our team members, just hearing them. The first quality to develop as a relational leader is the ability to understand how people feel and think. As you work with others, recognize that all people, leaders or followers, have some things in common:

- They like to feel special, so sincerely compliment them.

- They want a better tomorrow, so show them hope.

- They desire direction, so navigate for them.

- They are selfish, so speak to their needs first.

- They get low emotionally, so encourage them.

- They want success, so help them win.

Take into account that you, as a leader, should be sensible. Be able to adapt your leadership style to the person you are leading.

2. Love people. Elvis Presley once sang three sentences that are powerful in dealing with people: I want you, I need you, I love you. People need to be loved and respected. You as a leader need to have empathy for others and a keen ability to find the best in people.

3. Help people. Usually people respect a leader who keeps their interests in mind. If your focus is on what you can put into people rather than what you can get out of them, they will love and respect you—and these create a great foundation for building relationships.

In our experiences, we discovered some ways to improve relationships. We suggest the following:

- Improve your mind. If you feel that your ability to understand people needs improvement, jump-start it by reading several books on the subject and then spend more time observing people and talking to them to apply what you have learned.

- Strengthen your heart. If you are not as caring toward others as you could be, get the focus off yourself. Make a list of little things you could do to add value to friends and colleagues. Then try to do one of them every day. Don't wait until you feel like it to help others, instead act your way into feeling.

- Repair a hurting relationship: Think of a valued long-term relationship that has faded; do what you can do to rebuild it. If you had a falling out, take responsibility for your part in it and apologize. A better approach is to understand, love, and serve that person.

Building effective relationships is difficult but it is not impossible. Whether you are a project manager or sponsor, focus on people and relationships. Take your time and persevere.

Relationship Templates

Table 4.1 in the Appendix provides a template for recording the outcome from the information gathering, talking, and follow-up process, and highlights what is important for each sponsor. Documenting this information provides an overview of client sponsors, their agendas, and knowledge about the projects they sponsor. Use it to plan strategies for building and sustaining the relationships.

Table 4.2 in the Appendix summarizes a series of seven steps to stronger relationships between project managers and sponsors. In short, “The project manager and sponsor are the ultimate power couple: They're stronger together than apart” (Bertsche, 2014, p. 50).

Client Expectations

The following are some things clients expect from project sponsors (as solution providers):

- Clients want active participation during the preliminary sales phase and contract negotiation and also during the rest of the project life cycle. The project manager should not be the only person at the customer site dealing with client management. The client sponsor wants to deal with the provider sponsor.

- Clients expect to establish and maintain a high-level client relationship. This means that the solution provider sponsor talks to the client sponsor frequently, and they deal with project strategy and issues together. The most important considerations are always what is best for project success.

- Clients expect the sponsor to assist the project manager in getting the project under way (planning, staffing, and so forth). Clients sense when the provider project manager feels alone or unsupported. Adequate levels of support demonstrate the maturity level or measure of advancement in project management discipline implementation of the provider organization.

- Clients want to know current information regarding main activities of the project. Information can be shared by phone, but we recommend that the project sponsor and project manager have a weekly meeting to keep both updated—twenty to thirty minutes may be enough, depending on the type of project.

- Clients want contractual agreements shared between themselves and the provider. This is fundamental and key for project success, but also takes a lot of time. All contractual matters usually have legal implications and may involve strategic decisions in areas in which the project sponsor needs to be involved. Lawyers are essential and very helpful in this matter.

- Clients want company policies conveyed by the project sponsor to project managers. Project sponsors are usually located at strategic levels in the organization and are more familiar with company policies.

- Clients expect provider sponsors to help project managers solve problems in which a business or strategic decision has to be made. The client pays the provider to add value.

- Clients want general managers and client managers to be kept advised about critical or significant project problems or issues. Because of the importance of these areas to a successful outcome, the relationship between the project sponsor and the project manager needs to be fluent, timely, and concise.

Sustaining Supplier-Client Relationships

The project sponsor has the responsibility of maintaining executive customer contact. Doing this with excellence requires knowing the client sponsor extremely well, being open and transparent, and being able to establish a good relationship. The basis of a good relationship is truth. The win-win approach has more benefits than disadvantages for project success.

In addition to a sponsor, an assigned executive from senior management can be helpful. This person's role may be ceremonial at times but involves an ongoing commitment from the supplier to the client. The executive knows his or her counterparts in the other organization and is familiar with the history of the relationship. This executive meets with the client during company visits, expresses the highest level of support from the company, and can be called on if an issue needs escalation to the top of the company. An assigned executive represents a known person. Invoking this practice conveys that the company cares deeply about its best clients and accords them preferential treatment. It may also be the competitive advantage that allows the relationship to move forward.

Establishing good relationships between client and provider sponsor requires time together. They must talk with each other. In Spain, for instance, it is common to take a long lunch during which people get to know more about one another's professional and personal objectives in an open environment. Professional relationships are human relationships; project sponsors also have personal and professional objectives for a particular project. The client wants to have a provider who is always available.

At the beginning of a project, the sponsor is actively involved. For instance, he or she helps validate and set the project mission, objectives, constraints, and main priorities and responsibilities during a project start-up meeting. Upper managers and senior executives who act as project sponsors must establish project priorities for their assigned projects. However, in the execution phase, sponsors play a more reactive role; they act when requested by the project manager or by the client organization.

Project sponsors need to be careful that they are not involved in all project problems because it may undermine the authority of the project manager. Only the problem or issues that need business or strategic support or decisions should be solved by the project sponsor.

Key traits that enable a relationship to be sustained include trust in each other, confidence that the other has the skills and wherewithal to accomplish his or her commitments, and openness about all things good, bad, and ugly. This may also require that the parties sign a nondisclosure agreement to ensure that competitive information does not leak out. Perceive the relationship as a collaboration rather than a competition.

When problems arise that do not appear solvable by the project team or linger beyond reasonable expectations, develop or invoke a clearly defined escalation path or flowchart. Having this process mapped out before it is needed indicates a powerful commitment to satisfying the client. Likewise, the client sponsor may need to be called on when unreasonable demands or work outside the contract comes up.

CASE STUDY

How a Project Manager Can Effectively Utilize Executive Sponsors

James Stephen Cummins (“Steve”), a Business Analyst III in Texas, shares a case study about managing up the organization. The case involves how IT needs all questions answered before starting their part and managing the volume of data (and issues related to management), while the risk department wants every source of data imaginable (without knowing what is in each source) but cannot answer every question on how it might be used. Three executive sponsors worked to mediate the situation to find common ground, aided by a project manager.

The Organization. The Trust Company was created by the state government as a special purpose entity to efficiently and economically manage, invest, and safeguard state funds and its various subdivisions. The Trust Company is first and foremost a fiduciary organization. As such, it is held to the highest standard of care imposed by either law or equity and is obligated to subordinate its own interest to those of its beneficiaries. The Trust Company's mission is to preserve and grow the state's financial resources by competitively managing and investing them in a prudent, ethical, innovative and cost-effective manner.

The Project: Implement a Risk Analytical Tool. The Investment Risk Team was responsible for ensuring that investments were “prudent.” A project was established to implement advanced mathematical modeling techniques to measure investment “returns” and “exposure risks” compared to industry standards, called benchmark indexes. A mathematical modeling tool was selected, but to build models the team needed benchmark data to compare portfolio results and risk. Of many thousands of benchmarks available, an obvious solution was to house the benchmark data in a database, which necessitated the involvement of the IT department.

The IT department needed requirements to design the database, outlining how the data would be managed and projecting data volume in order to size a new server.

The two major stakeholders faced the following obstacles: IT wanted details relating to model, data source, frequencies, formats, sites, and responsibility for data integrity—before estimating work effort or beginning database planning. On the other hand, the Risk Department, which had initially selected five major benchmark providers, wanted all data sources automated and fed into the database. The Risk Department appeared to not understand the complexity of data management or data integrity, and could not answer what types of questions would be asked/answered. Each of the primary stakeholders went to their executive sponsor to complain about the other. IT did not want to commit to a database development until fully understanding the data, and Risk believed IT was obstructing their every move.

Executive Sponsor Culture. Executive sponsors at the Trust Company play an active role in all projects assigned to them. There are monthly Project Prioritization Committee Meetings attended by all executives where each active and potential project is reviewed. Each project lead provides project status, and executives ask pertinent questions. Each project lead should be prepared to respond to any inquiry. After status is reviewed, project priority is updated. Priorities are changed only if new information makes the change advisable. In addition to probing questions, executives listen to and frequently follow the advice of project participants or explain big picture reasons why they want to go in different directions.

Dig Deeper. The project manager first prepared himself by understanding needs of both sides in the debate. It could all be reduced to volume of data. The project manager dug deeper with the risk analyst about the mathematical models and was able to help reduce the number of benchmarks that needed to be automated. While greatly reducing the volume, the issue of data management still remained.

Know the Alternatives. One clear alternative option was to use a data feed vendor, thereby reducing daily data management work and offering a single point of contact for problem resolution. The project manager negotiated with the IT manager and IT analyst to accept this option as the preferred data delivery method.

Gather Information. The project manager and IT analyst gathered information on data feed vendors in general and two specific vendors, through phone conversations, test files, and face-to-face visits. They prepared a list of basic requirements and in-depth research from an industry alliance group.

Be Prepared. When he was confident that he was prepared, the project manager scheduled a series of conversations with the CFO executive sponsor to explain the benefits and drawbacks of the different data delivery options (multiple direct versus single aggregated).

Executive Sponsors in Action. A short time afterwards, the CFO, chief investment officer, and the chief executive officer (CEO) were together on an unrelated due diligence site visit. While observing IT operations, they learned that the company had eight full-time data analysts who “scrubbed the data” every day from multiple data providers. The CFO, having been educated on the benefits of a data feed vendor, told the other two that they should pursue the vendor approach. Having seen and heard from an external company about the resources it took to maintain daily data, the CEO commented, “We are not going to do this in house.”

Conclusion. Using negotiation, preparation, and the influence of executive sponsors, the major obstacles were substantially removed. The CFO instructed the IT department to start the database using the information that was currently available. The chief investment officer told the risk manager that a data feed vendor would be used for daily data scrubbing and delivery. The project moved forward and achieved its intended results.

Insights from Clifford Cohen, IT Manager

Few people really know why the sponsor is considered the sponsor and why it is important to understand exactly why the person's role—and the reason for that role—needs to be clear. Whenever I found myself talking to a “user champion” who thought he was a sponsor, I quickly corrected the situation by identifying a sponsor and clarifying the extent of the user champion's responsibilities. If I was in a meeting and someone referred to anyone as a sponsor who was not one by definition, I reminded everyone why this was inappropriate and ultimately deleterious to the success of the project. If one person assumed both roles, I would deal with him as if he were two different people. I never mixed discussion appropriate for one role with that of another role. I would meet with the individual and discuss project status, strategic direction, personnel issues, risks, and other sponsorship matters in one meeting and raise system requirement and functionality issues in another one.

This constant and strict adherence to role clarity was perhaps the single most effective thing I brought to troubled projects. My sponsors welcomed this clarity and moderated their input and influence accordingly, based on the situation once they saw the wisdom of it. The bottom line with me was that only through such diligence was it possible to ensure that all key roles were being played and being played right. In every case, my first action on taking over a troubled project was to clarify roles. Doing so never failed to impress both the business side and the technical side and made my job much easier from the outset.

Summary

This chapter addresses relationship building in general and the sponsorship role in the very specific form of a project-based organization in which providers conduct projects on behalf of clients. Extra effort is required to build and maintain successful relationships. Trust in each other is vital to every partnership. Important actions are to be trustworthy and credible. Pay attention to clues about what motivates people involved in project-based work; for example, gather information about each other, talk frequently, follow through on commitments, and perhaps deal with hidden agendas.

Expectations are high in these business transactions. Some key points to consider are: Know that clients want active and sustaining participation from the provider sponsor throughout the project life cycle, find out specifically how clients want their needs met, focus on ensuring that excellence in project sponsorship is a competitive advantage that keeps customers wanting to do business with you, and commit to exploring your values and behaviors that gain the credibility required for successful relationships.