Chapter 14

THE BEACON

When Dr. Gregory J. Trench finished his telephone conversation on an unseasonably warm evening in early January 1998, he was wearing a contented smile. The forty-four-year-old physician had been talking to his friend Leonard Richter, who had told him what he wanted to hear: the team was now complete. The team in question had nothing to do with his medical training and everything to do with his religious beliefs. To understand the connection, one must begin with the story of Trench’s conversion to an esoteric faith.

Dr. Trench came from a Catholic family of second-generation Irish immigrants. His grandfather, Tobias Trench, arrived in America from Dublin in 1908 and settled in Chicago, where he opened a small printing shop specializing in religious literature. By the time Gregory was born, in 1954, it was his father, Theodore, who was running the business, which now also included a bookstore: “The Beacon.” Besides its stock of religious publications, the store, located in the basement of the renovated family house, also carried a large selection of books on related subjects ranging from history and philosophy to astrology and esotericism.

Theodore and his American wife Mary Ann were both Roman Catholic. But unlike the woman, who observed the rites and precepts of her creed to the letter, Theodore was not particularly devout. His practice of religion seemed more a matter of tradition than conviction. Even though the couple’s two boys and two girls had been baptized, the father was reluctant to impose the Catholic faith on them. “I shall not indoctrinate my children,” he would say to a disapproving and disappointed Mary Ann. “They are intelligent enough to find their own way. Why would the Lord have given us a brain if we were not supposed to use it?” Far from indoctrinating them, he incited his offspring to be wary of those preaching “the final and absolute truth” in religious or secular matters, and to be open-minded and trust their own judgment.

Gregory was especially receptive to his father’s advice. An avid reader at an early age, he took advantage of the shelves of books around him and resorted to the local branch of the city’s public library for the literary genres missing from his father’s store, notably fiction and science books.

Of the four Trench children, Gregory was the only one to pursue a college education, and in 1979 he graduated top of his class from the Northwestern University School of Medicine. For the next fifteen years, life followed its predictable course for a brilliant young doctor in an affluent society: he completed his internship and specialization—in orthopedics—joined the staff of a private clinic, got married—to Terry Blum, an accountant and financial advisor—and bought a magnificent house in the upper-class Evanston suburb, just north of Chicago. As Dr. Trench’s medical practice flourished, so did the couple’s assets, with the help of Terry’s shrewd investment decisions. It didn’t take long for Gregory and Terry to become multimillionaire-rich.

Despite their wealth, during all those prosperous years the couple led a rather mundane existence. They had no children and didn’t do much socializing; work was their favorite activity and pastime, punctuated with the occasional vacation or family gathering. As for religion, they no longer practiced the faith of their respective parents—Terry came from a Jewish family—or any other faith, for that matter. But that is not to say that Gregory, in particular, was totally indifferent to spiritual or religious questions. In fact, he had not lost his appetite for reading but had become more selective about the subject matter: he had developed a keen interest in the history of religion.

He was also a regular participant in an online forum where questions about the history, psychology, and philosophy of religion were discussed. “The Crucible” had been initiated by Peter Graham, a Canadian Anglican priest. His primary motivation for creating the forum was to fight religious intolerance and to foster a better understanding among believers of different creeds, with some kind of reconciliation of all religions as the ultimate goal. He dreamed of a world free from sterile and divisive fights over which religion is the “true” one, a world in which worshippers of every faith would respect each other and equally honor the teachings and messages of Buddha, Moses, Jesus, Mohammed, or Guru Nanak.

People of all denominations together with atheists and skeptics and the inevitable crackpot logged onto the site, some disillusioned and pessimistic, others full of hope and compassion, all offering their opinion and advice on a wide variety of topics with the common thread of the notions of “God” and “religion.”

There were those who would use the forum to mount provocative attacks against religious beliefs:

“Consider (a) ‘My religion forbids me to kill (or to eat beef, or . . . )’ and (b) ‘My conscience forbids me to kill (or to eat beef, or . . . ).’ Is (a) more respectable than (b) just because ‘religion’ is mentioned? What’s the difference between a ‘religious’ belief and a ‘nonreligious’ one if both are deeply and sincerely held? If a person believes that extraterrestrials visited the earth or that Americans never landed on the moon, why should those beliefs be taken less seriously than, say, believing in angels or that after death we go to heaven (or to hell)?

“Using the alleged ‘religious’ character of some beliefs to demand special treatment, privileges, or fiscal advantages is unfair and discriminatory. When will the artificial distinction between ‘religious’ and ‘nonreligious’ beliefs end and the rights of all believers be equally respected?”

Others would argue for tolerance toward different kinds of religious practice, as advocated in “Song of the Hindu,” a poem composed around 5000 BC by Karkarta Bharat, the supreme chief of the Hindu clan, and transferred by oral tradition into the written Vedas several thousand years later:

“Each man has his own stepping stones to reach the One-Supreme. . . .

“God’s grace is withdrawn from no one; not even from those who have chosen to withdraw from God’s grace.

“Why does it matter what idols they worship, or what images they bow to, so long as their conduct remains pure.

“There can be no compulsion; each man must be free to choose the path to his gods.

“A Hindu may worship Agni (fire) and ignore all other deities. Do we deny that he is a Hindu?

Another may worship God through an idol of his choosing. Do we deny that he is a Hindu?

Yet another will find God everywhere and not in any image or idol. Is he not a Hindu?

“How can a scheme of salvation be limited to a single view of God’s nature and worship?

“Isn’t God an all-loving universal God?”

There were echoes of Reverend Graham’s own appeal against dogmatic barriers in this 7,000-year-old poignant plea for freedom of adoration. Sometimes, the convergence of views across the millennia can be truly astonishing.

A posting by a certain Tom Riley caught Trench’s eye one evening, late in the spring of 1994. It vaunted the merits of Neo-Pythagoreanism, an ancient syncretistic religion—that is, one combining different religious and philosophical beliefs—seeking to interpret the world in terms of numbers and arithmetical relationships.

“The origins of Neo-Pythagoreanism,” Riley wrote, “can be traced back to a school of philosophy based on the teachings of the famous Greek philosopher and mathematician Pythagoras that became prominent in Alexandria in the 1st century AD. Number One, or Monad, denoted to the Neo-Pythagoreans the principle of Unity, Identity, Equality, and conservation of the Universe, which results from persistence in Sameness. Number Two, or Dyad, signified the dual principle of Diversity and Inequality, of everything that is divisible or mutable, existing at one time in one way and at another time in another way. Similar reasons applied to their use of other numbers.

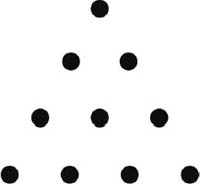

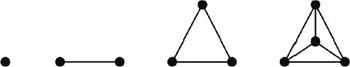

Numbers could also be arranged in geometrical shapes, the most perfect of which is the Tetraktys (=Quaternary) consisting of the first four integers disposed in a triangle of ten points, where the number four is represented by all three sides of the equilateral triangle.

In this context, one represents the point; two represents the line; three, the surface, and four represents the tetrahedron, the first three-dimensional figure.

The Tetraktys

Hence, in the realm of space the Tetraktys represents the continuity linking the dimensionless point with the manifestation of the first body, while in the realm of music the Tetraktys contains the mathematical ratios that underlie the harmony of the musical scale: 1:2, the octave; 2:3, the perfect fifth; and 3:4, the perfect fourth. These ratios are represented by successive pairs of lines beginning from any vertex. For the Neo-Pythagoreans, then, the Tetraktys is the perfect symbol for the numerical-musical order of the cosmos.”

The text explained that for the Neo-Pythagoreans there was a fundamental distinction between the soul and the body. Their religion was a purely contemplative one; they sought harmony, wisdom, and understanding for themselves and did not care about making converts or changing the world, “and in this sense Neo-Pythagoreanism is an inherently ‘pacific’ and tolerant religion,” Riley wrote, “respectful of other faiths or beliefs.” God must be worshipped spiritually by prayer and the will to be good, not in outward action. The soul must be freed from its material envelope by an ascetic way of life. Bodily pleasures and sensuous impulses must be forgone as detrimental to the spiritual purity of the soul.

“The ancient Pythagoreans,” Riley concluded, “preached the virtues of a vegetarian diet and were against the killing of animals and eating animal flesh. The current interest in vegetarianism and a humane attitude toward animals have their roots in Pythagoras’ teachings. Voltaire described Pythagoreanism as ‘the only religion in the world that was able to make the horror of murder into a filial piety and a religious feeling.’ Actually, before the term ‘vegetarian’ was coined around 1842, ‘Pythagorean’ was the common name for those who abstained from eating meat.”

The mysterious Neo-Pythagoreans struck a chord in Trench, and he wanted to learn more about the rites and tenets of their ancient religion. A Google search turned up 412 results on “Neopythagoreanism,” most of them short passages from academic articles or entries from various encyclopedias repeating essentially the same thing:

Very little is known of the members of this school. The Neo-Pythagoreans had no priests or leaders other than Pythagoras himself who, out of reverence, was never named. They referred to him as “the Man” or “the inventor of the Tetraktys.” A sect of Neo-Pythagoreans was founded in the first century AD by Roman aristocrats who, true to their obsession with secrecy, literally went underground to practice their beliefs. In what is now the historic center of Rome, they built a subterranean basilica, the ruins of which were discovered in 1917. The Roman sect disappeared in the third century, but similar groups are known to have existed at different times and places throughout history.

Not entirely happy with the results of his search, Trench e-mailed Riley, asking him whether he knew of any group of Neo-Pythagoreans in the United States. He suspected the man—if he was indeed a man—of being himself a member of one such circle. Riley’s brief reply, a few days later, was inconclusive: “It’s not impossible. How would I know? These people are very secretive. Why do you ask?” Good question. Trench wasn’t sure of the answer, or perhaps he didn’t want to admit to himself that his interest in the enigmatic Pythagoras and his followers was becoming obsessive. During the following months, he read all he could lay his hands on about Pre-Socratic philosophy, the early Pythagoreans and, foremost, the life of Pythagoras.

In the fall of 1994, Trench’s tranquil and mostly happy existence was abruptly shattered. One evening, as she was walking back home after her jogging session, Terry was hit by a car that had run a red light. Rushed to the hospital, she never regained consciousness and was declared dead two hours later with an inconsolable Gregory at her bedside.

After the funeral, Trench took a three-week leave from the clinic. Terry’s sudden death would have a dramatic effect on his behavior, or perhaps her absence only precipitated a process that was already in progress. In the space of a few weeks, his personality underwent a radical transformation. He became withdrawn and solitary, and avoided the company of even his closest friends. His parents invited him to spend some time with them in San Diego, where they had moved after his father retired, but he preferred to stay home reading, surfing the Internet, and working out in his well-equipped basement gym.

Going through his e-mail one morning he found a short note from Riley: “Still interested in ancient truths? I might be able to help. Tom Riley.” An exchange of messages followed and a meeting was arranged.

Two days later, at three o’clock in the afternoon, Trench was sitting at one of the tables in the spacious Starbucks store at the intersection of Lake and LaSalle, in downtown Chicago, with a huge, steaming mug of black coffee in front of him. He didn’t have to wait long. “Dr. Trench?” The female voice came from behind him. He turned around to face her. The woman smiled, amused at the surprised look in his eyes as she introduced herself: “I’m Gloria Sweeny, alias Tom Riley.”

They shook hands. She was a diminutive older lady, well past her sixties, wearing a dark suit and holding on to a disproportionately large purse. She sat down and began to talk before Trench could ask for an explanation.

“I’m here on behalf of a group of people having . . . how shall I put it? Some common interests. We call ourselves ‘The Beacon.’ ”

Strange, Trench thought. That was the name of his father’s bookstore until he sold it when he retired.

“We believe,” Ms. Sweeny went on, “that you might be interested in participating in a project of ours.”

“I very well might, if only you could be a bit more specific.” Trench spoke for the first time; he had trouble adjusting to the new Mr. Riley.

“Of course, but let me first ask you a question: Do you care about the future of the world? I mean, the future of the human race.”

“Of course I care. Who wouldn’t? But I don’t see the point.”

“You will soon. Let me ask you another question: Take a look at the state of the world. What do you see?” Before he had time to reply, she answered her own question: “War, widespread poverty, population explosion, rampant epidemics, religious fanaticism, nuclear irresponsibility, air, soil, and water pollution, fish stocks and cultivable land depletion, deforestation, global warming. Not a very pretty picture. And who do you think will be able to fix the mess we’re in? National governments? The UN? The multinational corporations? The scientists? The power of prayer? Certainly not the Church, whose business is to save souls, not the planet. And even less can we count on our typical politicians, short-sighted and controlled by the special interest groups who got them elected, when not downright corrupt.”

She painted a rather gloomy picture. Trench still couldn’t see what the woman was driving at. He had come expecting to learn more about the ancient Pythagoreans and their cult and was now beginning to wonder whether he had wasted his time. Too polite to just get up and leave, he resigned himself to hear the lady out. As if she had read his thoughts, her next question was more to the point.

“What do you know about Pythagoras, I mean, the kind of man he was?”

“Well, from what I’ve read, he was an extraordinary man, a man of many talents, a great thinker, and a brilliant mathematician. He was above all a spiritual leader—and also a political one, you may say—with a superior mind and a magnetic personality. The personage fascinates me, and I wish we had someone of his caliber around today.”

“I couldn’t agree more! But why settle for less, why settle for ‘someone of Pythagoras’ caliber?’ ” There was a pause while Trench tried to figure out what she meant.

“I’m not following you. . . .”

“Dr. Trench, what would you say if I told you that, at this very moment, Pythagoras may be among us, living somewhere in the world? And I don’t mean someone like Pythagoras, but the Man himself.”

“Now you’ve completely lost me. Is this some kind of joke?”

“I’ve never been more serious; but I can understand your bewilderment. I’m going to tell you a story. Please listen without interrupting me until I finish. I’ll be glad to answer any questions later.”

Trench took a sip of lukewarm coffee. The woman was searching for something in her purse. Her left hand came out holding a leather-covered flask, and he noticed that she was wearing a silver ring with a white stone. She unscrewed the top, took a long gulp, replaced the top, and quickly put the flask back in her purse. Trench had watched the entire operation in silence. When their eyes met, she smiled, said “My medicine,” and began her story.

“As you know, Pythagoras lived in the sixth century BC. What we know about him and his school was transmitted to us mostly through the writings of Greek historians. By some accounts, Pythagoras was a demigod endowed with supernatural powers, son of the god Apollo and the human Phytais. According to other sources, his father was Mnesarchus, a tradesman from the Island of Samos. While Mnesarchus was at Delphi on a business trip, he was told by the oracle that his soon-to-be-born son would ‘surpass all men who had ever lived in beauty and wisdom, and that he would be of the greatest benefit to the human race.’

“Unfortunately, that happened 2,500 years ago, and it is today that the human race could most benefit from Pythagoras’ wisdom and supernatural powers.”

Trench was about to ask something but remembered he had agreed not to interrupt her. The woman went on.

“Now, the works of Greek historians and philosophers that are our main source on Pythagoras were written several centuries after his death. Some of these works hint at the existence of an older and more reliable set of documents on the Man and his philosophy, a first-hand account written by some of his disciples shortly after Pythagoras’ death and meant to preserve their Master’s teachings, but only among the closed circle of the Pythagoreans and their descendants.”

She paused and moistened her lips. Trench sensed that the woman was approaching the story’s high point.

“One of the members of our group, I shall call him Mr. S, traveled extensively throughout Europe and the Near and Middle East, visiting libraries, archives, and antiquarian book dealers, including underground traders and private collectors, in search of some trace of the documents supposedly written by Pythagoras’ disciples. Although he didn’t find any of these, he did discover compelling evidence, such as verbatim quotations from very reliable sources, pointing to an extraordinary fact: around the years of the 680th Olympiad, Pythagoras would be reincarnated to ‘combat the evil.’ Now, the years of the 680th Olympiad in the ancient Greek calendar correspond to the middle of the twentieth century. . . .”

She looked intently at Trench. If she had expected some reaction from him, the doctor disappointed her.

“Mr. S then founded The Beacon,” she went on, “a select society of worshippers of Pythagoras whose main purpose is to find the Man reincarnate, the only person who can save the human race from extinction and prevent the disappearance of intelligent life from this planet. He’ll become our Master, Dr. Trench. He will lead and we shall follow.”

Trench thought: Her “society” sounds to me very much like a sect of Neo-Pythagoreans.

“But there’s more,” she continued. “Mr. S’ research also revealed that the clues that would allow us to recognize Pythagoras were contained in a parchment or papyrus written by one of his followers, or maybe by the Master himself. The original document has almost certainly been lost or destroyed, but some sources point to the existence of a well-preserved copy waiting to be found by someone who would know where to look and what to look for.

“Would you be interested in joining our group and help us find Pythagoras, Dr. Trench? We need all the help we can get—from people we trust, of course.”

It was a direct question. Trench was beginning to assess all its implications when Ms. Sweeny spoke again:

“Naturally, like any other potential member you would have to undergo an acceptance process: answer some questions, disclose some facts about yourself, that kind of thing. We need to find out how serious your intentions really are. And we would expect you to devote all your time and energies to our common cause.”

A strange thing then happened to Trench. A few moments earlier he would have regarded the woman’s offer to become a member of her mysterious circle as preposterous: How could she dare imagine he would abandon a successful and lucrative medical practice to join a bunch of religious freaks believing in reincarnation?

But the next moment it struck him, with the force of a revelation, that accepting the woman’s offer was the right thing to do, that for some obscure but compelling reason it was an opportunity not to be missed. As if in a dream, he heard himself saying, “Just tell me what I have to do to join The Beacon.”

At the end of his three-week leave, Trench did not return to work. When his secretary called to find out what was going on, she listened in disbelief as he spoke in a calm but resolute voice: “I’m not coming back, Sarah. Please tell Dr. Thompson that my letter of resignation will be on his desk by tomorrow. My attorney will take care of the loose ends and the legal stuff. I’m going to take a trip and won’t be around for a while. Don’t worry, I’m alright. I know what I’m doing. Thanks for everything.” And he hung up.