CHAPTER 2

Fishing for Ideas: Where Can We Find Good Strategies?

This is the surprise: Finding a trading idea is actually not the hardest part of building a quantitative trading business. There are hundreds, if not thousands, of trading ideas that are in the public sphere at any time, accessible to anyone at little or no cost. Many authors of these trading ideas will tell you their complete methodologies in addition to their backtest results. There are finance and investment books, newspapers and magazines, mainstream media websites, academic papers available online or in the nearest public library, trader forums, blogs, and on and on. Some of the ones I find valuable are listed in Table 2.1, but this is just a small fraction of what is available out there.

In the past, because of my own academic bent, I regularly perused the various preprints published by business school professors or downloaded the latest online finance journal articles to scan for good prospective strategies. In fact, the first strategy I traded when I became independent was based on such academic research. (It was a version of the PEAD strategy referenced in Chapter 7.) Increasingly, however, I have found that many strategies described by academics are either too complicated, out of date (perhaps the once-profitable strategies have already lost their power due to competition), or require expensive data to backtest (such as historical fundamental data). Furthermore, many of these academic strategies work only on small-cap stocks, whose illiquidity may render actual trading profits far less impressive than their backtests would suggest.

TABLE 2.1 Sources of Trading Ideas

| Type | URL |

|---|---|

| Academic | |

| Business schools' finance professors' websites | www.hbs.edu/research/research.html |

| Social Science Research Network | www.ssrn.com |

| National Bureau of Economic Research | www.nber.org |

| Business schools' quantitative finance seminars | www.ieor.columbia.edu/seminars/financialengineering |

| Quantpedia (aggregator of all academic papers on quantitative trading strategies!) | quantpedia.com |

| Financial blogs and podcasts | |

| Flirting with Models | www.thinknewfound.com |

| Mutiny Fund | mutinyfund.com/podcast/ |

| Chat with Traders | chatwithtraders.com |

| Eran Raviv | eranraviv.com |

| Sibyl/Godot Finance | godotfinance.com |

| Party at the Moontower | moontowermeta.com |

| My own! | epchan.blogspot.com |

| Trader forums | |

| Elite Trader | www.Elitetrader.com |

| Wealth-Lab | www.wealth-lab.com |

| Benn Eifert | @bennpeifert |

| Corey Hoffstein | @choffstein |

| Quantocracy (retweet of new articles) | @Quantocracy |

| Mike Harris | @mikeharrisNY |

| Euan Sinclair | @sinclaireuan |

| My own! | @chanep |

| Newspaper and magazines | |

| Stocks, Futures and Options magazine | www.sfomag.com |

This is not to say that you will not find some gems if you are persistent enough, but I have found that many traders' forums or blogs may suggest simpler strategies that are equally profitable. You might be skeptical that people would actually post truly profitable strategies in the public space for all to see. After all, doesn't this disclosure increase the competition and decrease the profitability of the strategy? And you would be right: Most ready-made strategies that you may find in these places actually do not withstand careful backtesting. Just like the academic studies, the strategies from traders' forums may have worked only for a little while, or they work for only a certain class of stocks, or they work only if you don't factor in transaction costs. However, the trick is that you can often modify the basic strategy and make it profitable. (Many of these caveats as well as a few common variations on a basic strategy will be examined in detail in Chapter 3.)

For example, someone once suggested a strategy to me that was described in Wealth-Lab (see Table 2.1), where it was claimed that it had a high Sharpe ratio. When I backtested the strategy, it turned out not to work as well as advertised. I then tried a few simple modifications, such as decreasing the holding period and entering and exiting at different times than suggested, and was able to turn this strategy into one of my main profit centers. If you are diligent and creative enough to try the multiple variations of a basic strategy, chances are you will find one of those variations that is highly profitable.

When I left the institutional money management industry to trade on my own, I worried that I would be cut off from the flow of trading ideas from my colleagues and mentors. But then I found out that one of the best ways to gather and share trading ideas is to start your own trading blog—for every trading “secret” that you divulge to the world, you will be rewarded with multiple ones from your readers. (The person who suggested the Wealth-Lab strategy to me was a reader who works 12 time zones away. If it weren't for my blog, there was little chance that I would have met him and benefited from his suggestion.) In fact, what you thought of as secrets are more often than not well-known ideas to many others! What truly make a strategy proprietary and its secrets worth protecting are the tricks and variations that you have come up with, not the plain-vanilla version.

Furthermore, your bad ideas will quickly get shot down by your online commentators, thus potentially saving you from major losses. After I glowingly described a seasonal stock-trading strategy on my blog that was developed by some finance professors, a reader promptly went ahead and backtested that strategy and reported that it didn't work. (See my blog entry, “Seasonal Trades in Stocks,” at epchan.blogspot.com/2007/11/seasonal-trades-in-stocks.html and the reader's comment therein. This strategy is described in more detail in Example 7.6.) Of course, I would not have traded this strategy without backtesting it on my own anyway, and indeed, my subsequent backtest confirmed his findings. But the fact that my reader found significant flaws with the strategy is important confirmation that my own backtest is not erroneous.

All in all, I have found that it is actually easier to gather and exchange trading ideas as an independent trader than when I was working in the secretive hedge fund world in New York. When I worked at Millennium Partners—a 40-billion-dollar hedge fund on Fifth Avenue—one trader ripped a published paper out of the hands of his programmer, who happened to have picked it up from the trader's desk. He was afraid the programmer might learn his “secrets.” (Lest you think that Millennium Partners is a bad place to work, I should add that its founder, Izzy Englander, personally spoke with my next employer to vouch for me.) That may be because people are less wary of letting you know their secrets when they think you won't be obliterating their profits by allocating $100 million to that strategy.

No, the difficulty is not the lack of ideas. The difficulty is to develop a taste for which strategy is suitable for your personal circumstances and goals, and which ones look viable even before you devote the time to diligently backtest them. This taste for prospective strategies is what I will try to convey in this chapter.

HOW TO IDENTIFY A STRATEGY THAT SUITS YOU

Whether a strategy is viable often does not have anything to do with the strategy itself—it has to do with YOU. Here are some considerations.

Your Working Hours

Do you trade only part time? If so, you would probably want to consider only strategies that hold overnight and not the intraday strategies. Otherwise, you may have to fully automate your strategies (see Chapter 5 on execution) so that they can run on autopilot most of the time and alert you only when problems occur.

When I was working full time for others and trading part time for myself, I traded a simple strategy in my personal account that required entering or adjusting limit orders on a few exchange-traded funds (ETFs) once a day, before the market opened. Then, when I first became independent, my level of automation was still relatively low, so I considered only strategies that require entering orders once before the market opens and once before the close. Later on, I added a program that can automatically scan real-time market data and transmit orders to my brokerage account throughout the trading day when certain conditions are met. So trading can be a “part-time” pursuit for you, even if you derive more income from it than your day job, as long as you trade quantitatively.

Your Programming Skills

Are you good at programming? If you know some programming languages such as Visual Basic or even Java, C#, or C++, you can explore high-frequency strategies, and you can also trade a large number of securities. Otherwise, settle for strategies that trade only once a day, or trade just a few stocks, futures, or currencies. These can often be traded using Excel loaded with your broker's macros. (This constraint may be overcome if you don't mind the expense of hiring a software contractor. Again, see Chapter 5 for more details.)

Your Trading Capital

Do you have a lot of capital for trading as well as expenditure on infrastructure and operation? In general, I would not recommend quantitative trading for an account with less than $50,000 capital. Let's say the dividing line between a high- versus low-capital account is $100,000. Capital availability affects many choices; the first is what financial instruments you should trade and what strategies you should apply to them. The second is whether you should open a retail brokerage account or a proprietary trading account (more on this in Chapter 4 on setting up your business). For now, I will consider instrument and strategy choices with capital constraint in mind.

With a low-capital account, we need to find strategies that can utilize the maximum leverage available. (Of course, getting a higher leverage is beneficial only if you have a consistently profitable strategy.) Trading futures, currencies, and options can offer you higher leverage than stocks; intraday positions allow a Regulation T leverage of 4, while interday (overnight) positions allow only a leverage of 2, requiring double the amount of capital for a portfolio of the same size. Finally, capital (or leverage) availability determines whether you should focus on directional trades (long or short only) or dollar-neutral trades (hedged or pair trades). A dollar-neutral portfolio (meaning the market value of the long positions equals the market value of the short positions) or market-neutral portfolio (meaning the beta of the portfolio with respect to a market index is close to zero, where beta measures the ratio between the expected returns of the portfolio and the expected returns of the market index) require twice the capital or leverage of a long- or short-only portfolio. So even though a hedged position is less risky than an unhedged position, the returns generated are correspondingly smaller and may not meet your personal requirements. For certain brokers (such as Interactive Brokers), they offer a portfolio margin, which depends on the estimated risk of your portfolio. For example, if your portfolio holds only long positions of risky small-cap stocks, they may require minimum 50 percent overnight margin (equivalent to a maximum leverage of 2). But if your portfolio holds a dollar-neutral portfolio of large-cap stocks, they may require only 20 percent or less of overnight margin. To sign up for portfolio margin, your broker may require that your account's net asset value (NAV) meets a minimum, often about $100K. But for that $100K of cash, you may be able to hold a portfolio that consists of $250K of long stock positions, and $250K of short stock positions.

Capital availability also imposes a number of indirect constraints. It affects how much you can spend on various infrastructure, data, and software. For example, if you have low trading capital, your online brokerage will not be likely to supply you with real-time market data for too many stocks, so you can't really have a strategy that requires real-time market data over a large universe of stocks. (You can, of course, subscribe to a third-party market data vendor, but then the extra cost may not be justifiable if your trading capital is low.) Similarly, clean historical stock data with high frequency costs more than historical daily stock data, so a high-frequency stock-trading strategy may not be feasible with small capital expenditure. For historical stock data, there is another quality that may be even more important than their frequencies: whether the data are free of survivorship bias. I will define survivorship bias in the following section. Here, we just need to know that historical stock data without survivorship bias are much more expensive than those that have such a bias. Yet if your data have survivorship bias, the backtest result can be unreliable.

The same consideration applies to news—whether you can afford a high-coverage, real-time news source such as Bloomberg determines whether a news-driven strategy is a viable one. Same for fundamental (i.e., companies' financial) data—whether you can afford a good historical database with fundamental data on companies determines whether you can build a strategy that relies on such data.

Table 2.2 lists how capital (whether for trading or expenditure) constraint can influence your many choices.

This table is, of course, not a set of hard-and-fast rules, just some issues to consider. For example, if you have low capital but opened an account at a proprietary trading firm, then you will be free of many of the considerations above (though not expenditure on infrastructure). I started my life as an independent quantitative trader with $100,000 at a retail brokerage account (I chose Interactive Brokers), and I traded only directional, intraday stock strategies at first. But when I developed a strategy that sometimes requires much more leverage in order to be profitable, I signed up as a member of a proprietary trading firm as well. (Yes, you can have both, or more, accounts simultaneously. In fact, there are good reasons to do so if only for the sake of comparing their execution speeds and access to liquidity. See “Choosing a Brokerage or Proprietary Trading Firm” in Chapter 4.)

Despite my frequent admonitions here and elsewhere to beware of historical data with survivorship bias, when I first started I downloaded only the split-and-dividend-adjusted Yahoo! Finance data using a now defunct program. But now you have easy and free access to that via many third-party APIs (more on the different databases and tools in Chapter 3). This database is not survivorship bias–free—but I was still using it for most of my backtesting for more than two years! In fact, a trader I know, who traded a million-dollar account, typically used such biased data for his backtesting, and yet his strategies were still profitable. How could this be possible? Probably because these were intraday strategies. So, you see, as long as you are aware of the limitations of your tools and data, you can cut many corners and still succeed. (There are now affordable survivorship-bias-free stock databases such as Sharadar, so I recommend you pay a small fee to use them.)

TABLE 2.2 How Capital Availability Affects Your Many Choices

| Low Capital | High Capital |

|---|---|

| Proprietary trading firm's membership | Retail brokerage account |

| Futures, currencies, options | Everything, including stocks |

| Intraday | Both intra- and interday (overnight) |

| Directional | Directional or market neutral |

| Small stock universe for intraday trading | Large stock universe for intraday trading |

| Daily historical data with survivorship bias | High-frequency historical data, survivorship bias–free |

| Low-coverage or delayed news source | High-coverage, real-time news source |

| No historical news database | Survivorship bias–free historical news database |

| No historical fundamental data on stocks | Survivorship bias–free historical fundamental data on stocks |

Though futures afford you high leverage, some futures contracts have such a large size that it would still be impossible for a small account to trade. For instance, though the E-mini S&P 500 future (ES) on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange has a margin requirement of only $12,000, it has a market value of about $167,500, and a 10 percent or larger daily move will wipe out your account that holds only the minimum margin cash. In case you think that a 10 percent or larger move for the S&P 500 index is extremely rare, check out how many times it happened from February to April 2020. Instead, you can trade the micro E-mini contracts (MES), which has only one-tenth of the margin requirement and market value of the regular E-mini.

Your Goal

Most people who choose to become traders want to earn a steady (hopefully increasing) monthly, or at least quarterly, income. But you may be independently wealthy, and long-term capital gain is all that matters to you. The strategies to pursue for short-term income versus long-term capital gain are distinguished mainly by their holding periods. Obviously, if you hold a stock for an average of one year, you won't be generating much monthly income (unless you started trading a while ago and have launched a new subportfolio every month, which you proceed to hold for a year—that is, you stagger your portfolios.) More subtly, even if your strategy holds a stock only for a month on average, your month-to-month profit fluctuation is likely to be fairly large (unless you hold hundreds of different stocks in your portfolio, which can be a result of staggering your portfolios), and therefore you cannot count on generating income on a monthly basis. This relationship between holding period (or, conversely, the trading frequency) and consistency of returns (that is, the Sharpe ratio or, conversely, the drawdown) will be discussed further in the following section. The upshot here is that the more regularly you want to realize profits and generate income, the shorter your holding period should be.

There is a misconception aired by some investment advisers, though, that if your goal is to achieve maximum long-term capital growth, then the best strategy is a buy-and-hold one. This notion has been shown to be mathematically false. In reality, maximum long-term growth is achieved by finding a strategy with the maximum Sharpe ratio (defined in the next section), provided that you have access to sufficiently high leverage. Therefore, comparing a short-term strategy with a very short holding period, small annual return, but very high Sharpe ratio, to a long-term strategy with a long holding period, high annual return, but lower Sharpe ratio, it is still preferable to choose the short-term strategy even if your goal is long-term growth, barring tax considerations and the limitation on your margin borrowing (more on this surprising fact later in Chapter 6 on money and risk management).

A TASTE FOR PLAUSIBLE STRATEGIES AND THEIR PITFALLS

Now, let's suppose that you have read about several potential strategies that fit your personal requirements. Presumably, someone else has done backtests on these strategies and reported that they have great historical returns. Before proceeding to devote your time to performing a comprehensive backtest on this strategy (not to mention devoting your capital to actually trading this strategy), there are a number of quick checks you can do to make sure you won't be wasting your time or money.

How Does It Compare with a Benchmark, and How Consistent Are Its Returns?

This point seems obvious when the strategy in question is a stock-trading strategy that buys (but not shorts) stocks. Everybody seems to know that if a long-only strategy returns 10 percent a year, it is not too fantastic because investing in an index fund will generate as good, if not better, returns on average. However, if the strategy is a long–short dollar-neutral strategy (i.e., the portfolio holds long and short positions with equal capital), then 10 percent is quite a good return, because then the benchmark of comparison is not the market index, but a riskless asset such as the yield of the three-month US Treasury bill (which at the time of this writing is just about zero percent).

Another issue to consider is the consistency of the returns generated by a strategy. Though a strategy may have the same average return as the benchmark, perhaps it delivered positive returns every month while the benchmark occasionally suffered some very bad months. In this case, we would still deem the strategy superior. This leads us to consider the information ratio or Sharpe ratio (Sharpe, 1994), rather than returns, as the proper performance measurement of a quantitative trading strategy.

Information ratio is the measure to use when you want to assess a long-only strategy. It is defined as

where

Now the benchmark is usually the market index to which the securities you are trading belong. For example, if you trade only small-cap stocks, the market index should be the Standard & Poor's small-cap index or the Russell 2000 index, rather than the S&P 500. If you are trading just gold futures, then the market index should be gold spot price, rather than a stock index.

The Sharpe ratio is actually a special case of the information ratio, suitable when we have a dollar-neutral strategy, so that the benchmark to use is always the risk-free rate. In practice, most traders use the Sharpe ratio even when they are trading a directional (long or short only) strategy, simply because it facilitates comparison across different strategies. Everyone agrees on what the risk-free rate is, but each trader can use a different market index to come up with their own favorite information ratio, rendering comparison difficult.

(Actually, there are some subtleties in calculating the Sharpe ratio related to whether and how to subtract the risk-free rate, how to annualize your Sharpe ratio for ease of comparison, and so on. I will cover these subtleties in the next chapter, which will also contain an example on how to compute the Sharpe ratio for a dollar-neutral and a long-only strategy.)

If the Sharpe ratio is such a nice performance measure across different strategies, you may wonder why it is not quoted more often instead of returns. In fact, when a colleague and I went to SAC Capital Advisors (assets under management then: $14 billion) to pitch a strategy, their then-head of risk management said to us: “Well, a high Sharpe ratio is certainly nice, but if you can get a higher return instead, we can all go buy bigger houses with our bonuses!” This reasoning is quite wrong: A higher Sharpe ratio will actually allow you to make more profits in the end, since it allows you to trade at a higher leverage. It is the leveraged return that matters in the end, not the nominal return of a trading strategy. For more on this, see Chapter 6 on money and risk management.

(And no, our pitching to SAC was not successful, but for reasons quite unrelated to the returns of the strategy. In any case, at that time neither my colleague nor I were familiar enough with the mathematical connection between the Sharpe ratio and leveraged returns to make a proper counterargument to that head of risk management. SAC pleaded guilty to insider trading charges and ceased to be a hedge fund in 2013.)

Now that you know what a Sharpe ratio is, you may want to find out what kind of Sharpe ratio your candidate strategies have. Often, they are not reported by the authors of that strategy, and you will have to email them in private for this detail. And often, they will oblige, especially if the authors are finance professors; but if they refuse, you have no choice but to perform the backtest yourself. Sometimes, however, you can still make an educated guess based on the flimsiest of information:

- If a strategy trades only a few times a year, chances are its Sharpe ratio won't be high. This does not prevent it from being part of your multistrategy trading business, but it does disqualify the strategy from being your main profit center.

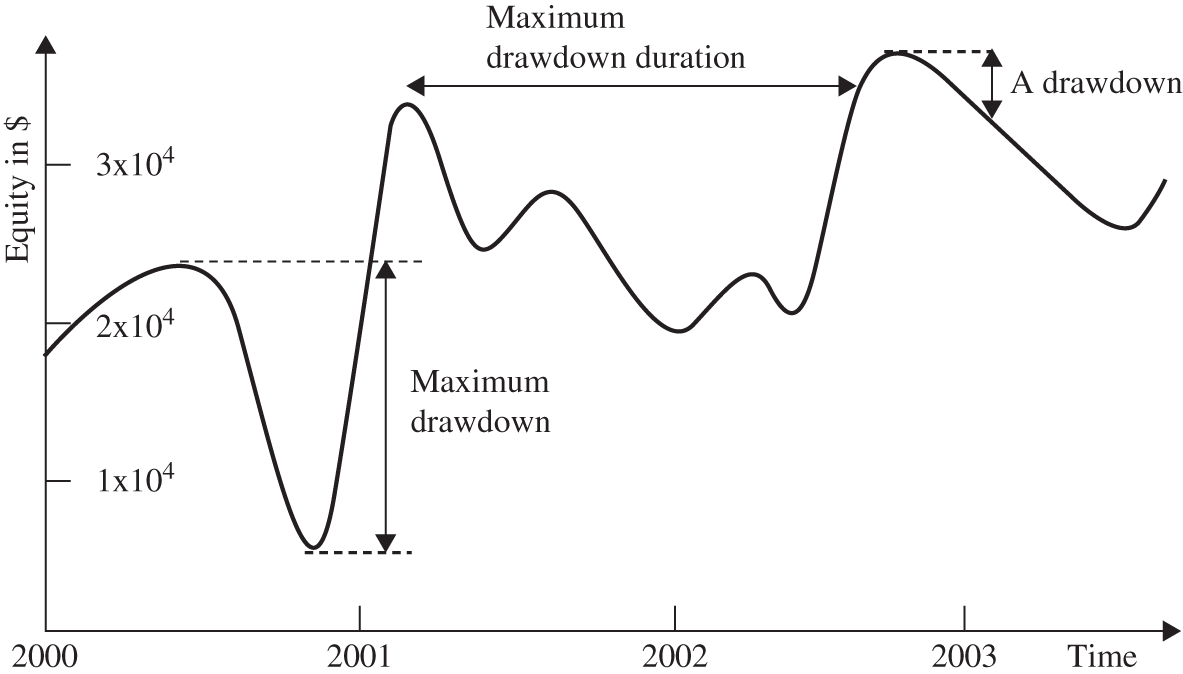

- If a strategy has deep (e.g., more than 10 percent) or lengthy (e.g., four or more months) drawdowns, it is unlikely that it will have a high Sharpe ratio. I will explain the concept of drawdown in the next section, but you can just visually inspect the equity curve (which is also the cumulative profit-and-loss curve, assuming no redemption or cash infusion) to see if it is very bumpy. Any peak-to-trough of that curve is a drawdown. (See Figure 2.1 for an example.)

FIGURE 2.1 Drawdown, maximum drawdown, and maximum drawdown duration.

As a rule of thumb, any strategy that has a Sharpe ratio of less than 1 is not suitable as a stand-alone strategy. For a strategy that achieves profitability almost every month, its (annualized) Sharpe ratio is typically greater than 2. For a strategy that is profitable almost every day, its Sharpe ratio is usually greater than 3. I will show you how to calculate Sharpe ratios for various strategies in Examples 3.4, 3.6, and 3.7 in the next chapter.

How Deep and Long Is the Drawdown?

A strategy suffers a drawdown whenever it has lost money recently. A drawdown at a given time t is defined as the difference between the current equity value (assuming no redemption or cash infusion) of the portfolio and the global maximum of the equity curve occurring on or before time t. The maximum drawdown is the difference between the global maximum of the equity curve with the global minimum of the curve after the occurrence of the global maximum (time order matters here: The global minimum must occur later than the global maximum). The global maximum is called the high watermark. The maximum drawdown duration is the longest it has taken for the equity curve to recover losses.

More often, drawdowns are measured in percentage terms, with the denominator being the equity at the high watermark and the numerator being the loss of equity since reaching the high watermark.

Figure 2.1 illustrates a typical drawdown, the maximum drawdown, and the maximum drawdown duration of an equity curve. I will include a tutorial in Example 3.5 on how to compute these quantities from a table of daily profits and losses using either Excel, MATLAB, Python, or R. One thing to keep in mind: The maximum drawdown and the maximum drawdown duration do not typically overlap over the same period.

Defined mathematically, drawdown seems abstract and remote. However, in real life there is nothing more gut-wrenching and emotionally disturbing to suffer than a drawdown if you're a trader. (This is as true for independent traders as for institutional ones. When an institutional trading group is suffering a drawdown, everybody seems to feel that life has lost meaning and spend their days dreading the eventual shutdown of the strategy or maybe even the group as a whole.) It is therefore something we would want to minimize. You have to ask yourself, realistically, how deep and how long a drawdown will you be able to tolerate and not liquidate your portfolio and shut down your strategy? Would it be 20 percent and three months, or 10 percent and one month? Comparing your tolerance with the numbers obtained from the backtest of a candidate strategy determines whether that strategy is for you.

Even if the author of the strategy you read about did not publish the precise numbers for drawdowns, you should still be able to make an estimate from a graph of its equity curve. For example, in Figure 2.1, you can see that the longest drawdown goes from around February 2001 to around October 2002. So the maximum drawdown duration is about 20 months. Also, at the beginning of the maximum drawdown, the equity was about $2.3 × 104, and at the end, about $0.5 × 104. So the maximum drawdown is about $1.8 × 104.

How Will Transaction Costs Affect the Strategy?

Every time a strategy buys and sells a security, it incurs a transaction cost. The more frequently it trades, the larger the impact of transaction costs will be on the profitability of the strategy. These transaction costs are not just due to commission fees charged by the broker. There will also be the cost of liquidity—when you buy and sell securities at their market prices, you are paying the bid–ask spread. If you buy and sell securities using limit orders, however, you avoid the liquidity costs but incur opportunity costs. This is because your limit orders may not be executed, and therefore you may miss out on the potential profits of your trade. Also, when you buy or sell a large chunk of securities, you will not be able to complete the transaction without impacting the prices at which this transaction is done. (Sometimes just displaying a bid to buy a large number of shares for a stock can move the prices higher without your having bought a single share yet!) This effect on the market prices due to your own order is called market impact, and it can contribute to a large part of the total transaction cost when the security is not very liquid.

Finally, there can be a delay between the time your program transmits an order to your brokerage and the time it is executed at the exchange, due to delays on the internet or various software-related issues. This delay can cause a slippage, the difference between the price that triggers the order and the execution price. Of course, this slippage can be of either sign, but on average it will be a cost rather than a gain to the trader. (If you find that it is a gain on average, you should change your program to deliberately delay the transmission of the order by a few seconds!)

Transaction costs vary widely for different kinds of securities. You can typically estimate it by taking half the average bid–ask spread of a security and then adding the commission if your order size is not much bigger than the average sizes of the best bid and offer. If you are trading S&P 500 stocks, for example, the average transaction cost (excluding commissions, which depend on your brokerage) would be about 5 basis points (that is, five-hundredths of a percent). Note that I count a round-trip transaction of a buy and then a sell as two transactions—hence, a round trip will cost 10 basis points in this example. If you are trading ES, the E-mini S&P 500 futures, the transaction cost will be about 1 basis point. Sometimes the authors whose strategies you read about will disclose that they have included transaction costs in their backtest performance, but more often they will not. If they haven't, then you just to have to assume that the results are before transactions, and apply your own judgment to its validity.

As an example of the impact of transaction costs on a strategy, consider this simple mean-reverting strategy on ES. It is based on Bollinger Bands: that is, every time the price exceeds plus or minus 2 moving standard deviations of its moving average, short or buy, respectively. Exit the position when the price reverts back to within 1 moving standard deviation of the moving average. If you allow yourself to enter and exit every five minutes, you will find that the Sharpe ratio is about 3 without transaction costs—very excellent indeed! Unfortunately, the Sharpe ratio is reduced to –3 if we subtract 1 basis point as transaction costs, making it a very unprofitable strategy.

For another example of the impact of transaction costs, see Example 3.7.

Does the Data Suffer from Survivorship Bias?

A historical database of stock prices that does not include stocks that have disappeared due to bankruptcies, delistings, mergers, or acquisitions suffer from survivorship bias, because only “survivors” of those often unpleasant events remain in the database. (The same term can be applied to mutual fund or hedge fund databases that do not include funds that went out of business.) Backtesting a strategy using data with survivorship bias can be dangerous because it may inflate the historical performance of the strategy. This is especially true if the strategy has a “value” bent; that is, it tends to buy stocks that are cheap. Some stocks were cheap because the companies were going bankrupt shortly. So if your strategy includes only those cases when the stocks were very cheap but eventually survived (and maybe prospered) and neglects those cases where the stocks finally did get delisted, the backtest performance will, of course, be much better than what a trader would actually have suffered at that time.

So when you read about a “buy on the cheap” strategy that has great performance, ask the author of that strategy whether it was tested on survivorship bias–free (sometimes called “point-in-time”) data. If not, be skeptical of its results. (A toy strategy that illustrates this can be found in Example 3.3.)

How Did the Performance of the Strategy Change over the Years?

Most strategies performed much better 10 years ago than now, at least in a backtest. There weren't as many hedge funds running quantitative strategies then. Also, bid-ask spreads were much wider then: So if you assumed the transaction cost today was applicable throughout the backtest, the earlier period would have unrealistically high returns.

Survivorship bias in the data might also contribute to the good performance in the early period. The reason that survivorship bias mainly inflates the performance of an earlier period is that the further back we go in our backtest, the more missing stocks we will have. Since some of those stocks are missing because they went out of business, a long-only strategy would have looked better in the early period of the backtest than what the actual profit and loss (P&L) would have been at that time. Therefore, when judging the suitability of a strategy, one must pay particular attention to its performance in the most recent few years, and not be fooled by the overall performance, which inevitably includes some rosy numbers back in the old days.

Finally, regime shifts in the financial markets can mean that financial data from an earlier period simply cannot be fitted to the same model that is applicable today. Major regime shifts can occur because of changes in securities market regulation (such as decimalization of stock prices or the elimination of the short-sale rule, which I allude to in Chapter 5) or other macroeconomic events (such as the subprime mortgage meltdown).

This point may be hard to swallow for many statistically minded readers. Many of them may think that the more data there is, the more statistically robust the backtest should be. This is true only when the financial time series is generated by a stationary process. Unfortunately, financial time series is famously nonstationary, due to all of the reasons given earlier.

It is possible to incorporate such regime shifts into a sophisticated “super”-model (as I will discuss in Example 7.1), but it is much simpler if we just demand that our model deliver good performance on recent data.

Does the Strategy Suffer from Data-Snooping Bias?

If you build a trading strategy that has 100 parameters, it is very likely that you can optimize those parameters in such a way that the historical performance will look fantastic. It is also very likely that the future performance of this strategy will look nothing like its historical performance and will turn out to be very poor. By having so many parameters, you are probably fitting the model to historical accidents in the past that will not repeat themselves in the future. Actually, this so-called data-snooping bias is very hard to avoid even if you have just one or two parameters (such as entry and exit thresholds), and I will leave the discussion on how to minimize its impact to Chapter 3. But, in general, the more rules the strategy has, and the more parameters the model has, the more likely it is going to suffer data-snooping bias. Simple models are often the ones that will stand the test of time. (See the sidebar on my views on artificial intelligence and stock picking.)

Does the Strategy “Fly under the Radar” of Institutional Money Managers?

Since this book is about starting a quantitative trading business from scratch, and not about starting a hedge fund that manages multiple millions of dollars, we should not be concerned whether a strategy is one that can absorb multiple millions of dollars. (Capacity is the technical term for how much a strategy can absorb without negatively impacting its returns.) In fact, quite the opposite—you should look for those strategies that fly under the radar of most institutional investors, for example, strategies that have very low capacities because they trade too often, strategies that trade very few stocks every day, or strategies that have very infrequent positions (such as some seasonal trades in commodity futures described in Chapter 7). Those niches are the ones that are likely to still be profitable because they have not yet been completely arbitraged away by the gigantic hedge funds.

SUMMARY

Finding prospective quantitative trading strategies is not difficult. There are:

- Business school and other economic research websites.

- Financial websites and blogs focusing on the retail investors.

- Trader forums where you can exchange ideas with fellow traders.

- Twitter!

After you have done a sufficient amount of Net surfing or scrolling through your Twitter feed, you will find a number of promising trading strategies. Whittle them down to just a handful, based on your personal circumstances and requirements, and by applying the screening criteria (more accurately described as healthy skepticism) that I listed earlier:

- How much time do you have for babysitting your trading programs?

- How good a programmer are you?

- How much capital do you have?

- Is your goal to earn steady monthly income or to strive for a large, long-term capital gain?

Even before doing an in-depth backtest of the strategy, you can quickly filter out some unsuitable strategies if they fail one or more of these tests:

- Does it outperform a benchmark?

- Does it have a high enough Sharpe ratio?

- Does it have a small enough drawdown and short enough drawdown duration?

- Does the backtest suffer from survivorship bias?

- Does the strategy lose steam in recent years compared to its earlier years?

- Does the strategy have its own “niche” that protects it from intense competition from large institutional money managers?

After making all these quick judgments, you are now ready to proceed to the next chapter, which is to rigorously backtest the strategy yourself to make sure that it does what it is advertised to do.

REFERENCES

- Duhigg, Charles. 2006. “Street Scene; A Smarter Computer to Pick Stock.” New York Times, November 24.

- Sharpe, William. 1994. “The Sharpe Ratio.” The Journal of Portfolio Management, Fall. Available at: www.stanford.edu/~wfsharpe/art/sr/sr.htm.