CHAPTER 5

PRIORITIZATION

Bringing Balance to the Force

To build vision-driven products, you’ve defined a clear vision and a strategy. Prioritization is how you can infuse your vision in your everyday decision-making.

In making everyday decisions, you’re intuitively balancing your long-term goals against short-term needs. If you worked purely in pursuit of the long-term vision without acknowledging the reality of survival, you may not survive long enough to make progress toward your destination. On the other hand, in the absence of a clear long-term purpose, your short-term goals, typically profitability and business needs, would become the sole focus. Building vision-driven products requires balancing progress toward the vision while dealing with the practicality of survival.

You may have developed an intuition for finding this balance through your years of hard experiences and learning through trial and error. To use a Star Wars analogy, through years of experience you may have learned to use the Force. However, in the corporate world, as in the movie, it seems that a select few in the organization have the Force and others don’t. Those who don’t have this intuition find it harder to make their own decisions and try new things—they have to await guidance from those who have it. Organizations would be more effective if everyone had the Force and dictating the right trade-offs didn’t fall to a few. It turns out that we all have the Force in us—we just need to learn to use it.

Cultivating this intuition in teams is not just a nice-to-have; it’s crucial for building vision-driven products. All individuals are contributing to the vision and are making trade-offs between the long term and the short term through their own work. A software developer could choose to spend time carefully building software for the long term or could write code quickly to deliver something in the short term and undertake major repairs later. No leader could dictate all the trade-offs at every level. To build vision-driven products, you’ll need to rely on every individual to make the right trade-offs.

You can scale your thinking across the organization by developing in others the same intuition you have for trade-offs. When you take this approach, you won’t need to micromanage because you’ll be influencing others to make decisions like you would, even when you’re not around.

The RPT approach to alignment on prioritization and decision-making gives teams and individuals autonomy to make decisions. Research shows that companies that offer autonomy are 10 times more likely to outperform traditional organizations in the short term and more than 20 times more likely to outperform them in the long term.1

This chapter helps you achieve these benefits by using a powerful two-by-two framework. It will help you infuse your vision into your everyday decision-making and give teams a shared intuition for making the right trade-offs.

VISUALIZING THE TRADE-OFFS

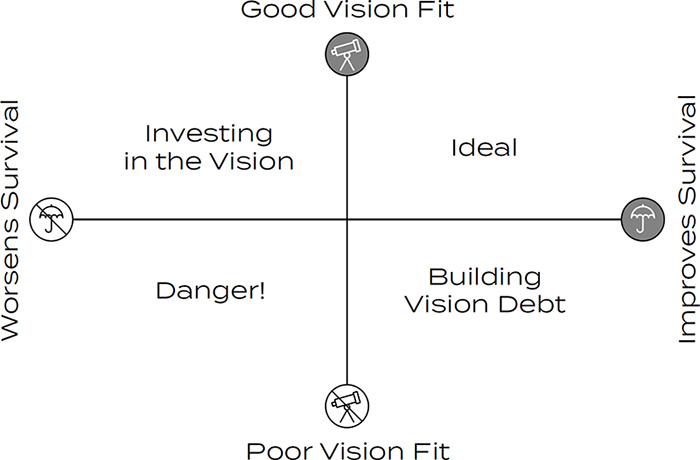

When you use intuition to prioritize and make business decisions, you’re essentially trading off between making progress toward your vision (vision fit) and mitigating short-term risk (survival). You can visualize balancing the two using the two-by-two rubric shown in figure 3.

In an ideal world, of course, everything you’re working on will be a good vision fit and help you survive. Realistically, however, many aspects of your decisions and priorities will represent trade-offs between vision fit and survival. Here’s how to think about the tradeoffs represented by the four quadrants of the rubric:

• Ideal quadrant: Items in the top right quadrant are those that most closely match your vision and improve survival by mitigating risk. These are the easy decisions. But focusing only on opportunities in the Ideal quadrant would mean a persistent focus on the immediate benefits.

• Investing in the Vision quadrant: To progressively deliver on the long-term vision, you need to also selectively pick projects in the Investing in the Vision quadrant. These are typically projects that will bring long-term benefits but increase risk in the short term.

• Building Vision Debt quadrant: Occasionally you may need to take on projects that reduce short-term risk but may be a poor fit for your vision; pursuing them results in vision debt. You have to take on vision debt very carefully, knowing that incurring too much will derail what your product stands for.

• Danger! quadrant: Items in the bottom left quadrant are a poor vision fit and expose you to additional risk. Pursue items in here only if they unlock important opportunities in the future.

FIGURE 3: RPT prioritization rubric using vision fit versus survival

Of these quadrants, decisions that fall in the Ideal and Danger! quadrants are the easiest. The harder decisions are in the Investing in the Vision and Building Vision Debt quadrants. If we want to build vision-driven products, our trade-offs should be more often in the Ideal and Investing in the Vision quadrants while avoiding Building Vision Debt and Danger! quadrants as much as possible.

MANAGING VISION DEBT

You incur vision debt when you put progress toward your product vision on hold to satisfy more immediate financial constraints. If you are in the tech industry, you may be familiar with its tech counterpart: technical debt. Accumulating tech debt leads to buggy software and brittle code, while accumulating an excess of Vision Debt leads to confused customers, demotivated teams, and a directionless product.

You’re probably taking on vision debt whenever you do one or more of the following:

• Build unique, custom solutions for each customer

• Add one-off features and integrations to your product just to close a sale

• Use a competitor’s technology, content, or data in the core of your product

• Build features that increase revenues but trade off user privacy and well-being

All of these activities represent opportunities to get to market faster, close deals, and increase revenues, but they move you further from achieving your vision. If you need the cash, however, taking on vision debt may be necessary. Just be sure to keep track of activities that incur vision debt, and make a plan with your team to pay it down later in your strategic road map.

But be careful. Like any debt, vision debt comes with compound interest. The longer your product has diverged from your core vision, the more difficult it will be to get executive and team buy-in to return to the central vision of your product.

Once you have chosen to incur vision debt, communicating this choice to your team is critical. Your team will quickly recognize that the product is moving away from the vision they’ve all been asked to buy into. Publicly recognize this fact, and describe the long-term strategic thinking behind it. By acknowledging vision debt, and explaining the plan to pay it back, you can mitigate any short-term damage to your team’s alignment and commitment to the vision.

Nidhi Aggarwal, founder of QwikLABS and cocreator of the Radical Product Thinking framework, was able to successfully leverage vision debt to build up a sustainable customer base in her startup’s early days. The product enabled students to easily access hands-on training labs to learn cloud computing configuration management. Two years after the launch, Aggarwal received a call from the company’s biggest customer. It wanted QwikLABS to develop specific labs just for its own use (more of a consulting arrangement than a product purchase).

Becoming a professional services company was not aligned with the QwikLABS vision but would help short-term survival and growth. After much debate, the QwikLABS leadership team decided to take on the vision debt, directing several developers to focus exclusively on creating content and features for this single client. Normally, this would be an example of the product disease Obsessive Sales Disorder, but Aggarwal and her executives were explicit in acknowledging to the team that this represented a short-term step away from the vision. Most importantly, they committed to a timeline for getting back on track, ensuring that the team saw this as a temporary but necessary detour, not as a top-down loss of confidence in the vision.

INVESTING IN THE VISION

When you invest in the vision, you indicate to your team through your actions that you value the vision and that it affects your decision-making. To get your team to buy into the vision more deeply, you need to role model investing in the vision.

You’re probably investing in the vision if you do the following:

• Spend time fixing technical debt (the technical shortcuts you took when building the product that helped you get to market faster): Addressing technical debt means you’re not working toward delivering an additional feature in the short term, but in the long term it gives you a stronger technological foundation to continue adding features.

• Spend resources on user research: Investing resources to conduct research may not yield immediately visible results, but it helps you build a better product in the long term.

• Invest in R&D: This activity doesn’t help your bottom line immediately, but unless you’re investing in R&D, your lead will eventually be eroded.

All of these activities represent opportunities to make progress toward the vision, but they don’t help your chances of survival in the short term. You’ll need to evaluate how much you can afford to invest in the vision based on the magnitude of your survival risk.

DEFINING SURVIVAL

A radical vision provides clarity on the long term when using the vision-fit-versus-survival rubric as a communication tool. Similarly, you’ll find that defining survival gives you a shared understanding of the biggest short-term risk that threatens your product. Making this definition explicit instead of relying on each person’s intuitive notion of survival helps ensure that everyone is aligned with the end goal in a way that helps you survive long enough to achieve that goal.

Survival is about identifying and mitigating the biggest risks that could shut you down. Your risks will evolve over time but typically fit within the five categories shown in figure 4.

Technology or operational risk is the risk that you might not be able to invent key technology or solve operational issues (such as scalability) that are critical to your business model. Legal or regulatory risk might result in your company being sued or otherwise legally prevented from operating. Your top concern may be personnel risk if your product would not survive the departure of key personnel. If you’re the founder of an early stage company, your biggest risk is usually running out of cash (financial risk). On the other hand, in a large company, even if your product is losing money, the company often has the ability to pull cash from its reserves or from other, more profitable operations to keep paying employees and suppliers. Your biggest risk may come from a powerful but skeptical stakeholder who wants to pull the plug on your product (stakeholder risk).

FIGURE 4: Survival risk—the biggest risk that could kill your product tomorrow

While all of these risks are important, not all of them are going to get you simultaneously, but like a gazelle, you can effectively run from only one or two at a time.

You can define your biggest risk by writing a Survival Statement—a sentence or two that encompasses the gravest and most immediate dangers to your product’s existence. This will work as the counterpart to your Radical Vision Statement.

The following fill-in-the-blanks statement makes it easy to craft a Survival Statement as a group exercise:

Currently, the greatest risk to our product’s existence is that [greatest risk].

If this happens, we won’t be able to continue operating because [consequences of risk].

This risk will most likely come true if [factors that increase or amplify risk].

Some factors that could help us mitigate this risk are [factors that decrease/mitigate risk].

EXAMPLES OF SURVIVAL STATEMENTS

For Likelii, a startup I founded in 2011 and sold in 2014, the risk that we couldn’t show product-market fit (and would thus be unable to raise additional funding) represented financial risk. This is the Survival Statement I would have written for Likelii:

Currently, the greatest risk to our product’s existence is that [we may not be able to raise venture funding].

If this happens, we won’t be able to continue operating because [we won’t be able to make payroll].

This risk will most likely come true if [we fail to demonstrate traction through user growth].

Some factors that could help us mitigate this risk are [ focusing on growing the user base over the next six months, giving us time to seek funding before our cash runs out].

A Survival Statement for a larger company may look different. When I was working at a large enterprise, our customers were cable companies with sales cycles measured in years. Our product addressed a key pain point and was much simpler and faster to use than existing products in the market. It effectively replaced multiple tools and interfaces that the end users were juggling, and this drove rapid adoption.

When the company was acquired by a much larger company, the new parent company had a similar product in its lineup, although it wasn’t nearly as easy to use (and in fact required a large support staff dedicated to helping customers with basic tasks). However, a large, politically powerful contingent within the parent company preferred the existing in-house solution.

This is the Survival Statement I would have written when I was heading up product management at that company:

Currently, the greatest risk to our product’s existence is that [we lose executive sponsorship for our product].

If this happens, we won’t be able to continue operating because [our budget will be zeroed out and our team will be reassigned to other projects].

This risk will most likely come true if [stakeholders don’t value the importance of the simplicity and speed of our product, and we have not gathered political capital by driving sales into new accounts].

Some factors that could help us mitigate this risk are [cultivating relationships with stakeholders at the acquiring company and getting their support while growing sales over the next year].

To write a Survival Statement, start by identifying all of the risks you can name within each of the five risk categories (financial risk, stakeholder risk, personnel risk, legal or regulatory risk, and technology or operational risk). Then, depending on your scenario, pick one or two of these classes of risk that might be nipping at your toes more than the others.

Once you’ve identified your biggest risk, think about the biggest consequences of this risk. What would happen if the risk were to come true? If our early stage startup failed to raise funds, we would no longer be able to pay employees, and that would kill our product. In a larger company, if a skeptical stakeholder were to pull the plug, we’d no longer have the resources to continue working on the product. One trick to identify the consequences is to keep asking “So what?” until you arrive at the final consequence.

Next, think about how you would mitigate your biggest risk. At an early stage startup, you may be able to mitigate risk by showing specific financial metrics to convince your investors that you are a worthwhile investment. In a larger company, if your biggest risk is losing stakeholder support, evaluate what may cause you to lose that support and how you could prevent it.

PUTTING THE PRIORITIZATION RUBRIC INTO ACTION

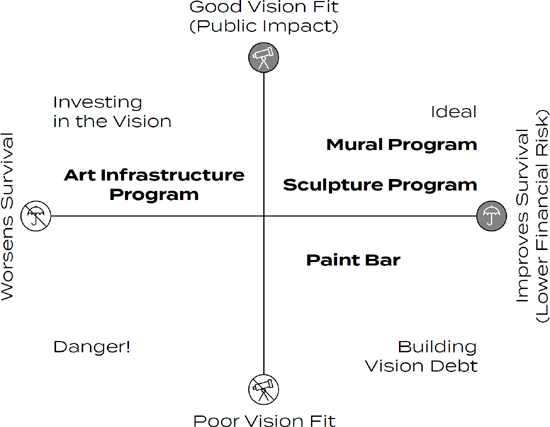

Using the vision-fit-versus-survival rubric for prioritization helps simplify the discussion on priorities and can become an ongoing communication tool. The Avenue Concept (TAC), a nonprofit in public art, used the two-by-two rubric to communicate its three-year strategic plan to the board and to its own team.

The organization, and specifically the executive director, Yarrow Thorne, had accomplished a series of major installations of public art including sculptures and murals and was laying the groundwork for art infrastructure in the city of Providence, Rhode Island. Over time, as awareness grew of TAC’s ability to complete public art installations in short periods of time, other organizations and even individuals began to reach out to the nonprofit to engage it on new projects.

TAC’s team members began to feel stretched thin across too many projects and were wary of catching Strategic Swelling. They realized the need to carefully manage their resources to maximize impact. The team used the two-by-two rubric to prioritize their strategic initiatives and shared these with the board so that the organization could plan its budget and resources appropriately. TAC began by defining the two axes:

• Vision: TAC’s vision was to create a deep social impact by bringing art into public awareness.

• Survival: For TAC, as for many nonprofits or startups, survival was defined as continued access to funding.

With these concepts defined, the TAC team evaluated and plotted opportunities into quadrants as shown in figure 5:

FIGURE 5: Prioritization rubric for The Avenue Concept

• Ideal quadrant: For TAC, the Sculpture and Mural Programs were close vision fits—they were both very visible and therefore raised awareness of public art. Because TAC’s executive director had crafted a model that allowed the team to scalably source and install artworks, these programs fit in the Ideal quadrant. But focusing only on opportunities in the Ideal quadrant would have been myopic.

• Investing in the Vision quadrant: To progressively deliver on the long-term vision, TAC was also selectively investing in projects in the Investing in the Vision quadrant. TAC’s Art Infrastructure Program installed lighting to highlight installations in the evenings. The lighting raised the visibility of the artworks in the dark and brought art into the evening ambiance—as a result, the program was high on the vision fit axis. But on the survival axis, developing this art infrastructure across the city was resource-intensive, so it presented a higher financial risk. TAC used the two-by-two framework to explain to the board that investing in the vision increased the organization’s fundraising needs and required the team to pick selectively from this quadrant.

• Building Vision Debt quadrant: One way of offsetting some of the fundraising requirements was to thoughtfully take on vision debt. The Paint Bar (TAC’s paint store and studio for local artists) was an example of using vision debt wisely to get to the next milestone. The Paint Bar didn’t create deep and meaningful impact through art for the public, but it brought in revenues through paint sales. It made creating murals more sustainable for TAC and promoted engagement with local artists.

• Danger! quadrant: TAC didn’t have opportunities in the Danger! quadrant.

TAC used this two-by-two framework to align its board and the team on its strategic plan and the rationale for the projects the team was selecting to deliver on the vision.

Similarly, at an executive level, you can evaluate your strategic initiatives and prioritize them based on the quadrants they fit in. You could also use these to discuss major sales opportunities and how they fit with the overall vision.

Product teams can use these to prioritize features. Start by drawing the two-by-two rubric on a whiteboard and restating your two axes (vision fit and survival). Write each feature on a sticky note and as a team decide which quadrant each feature belongs in.

Most likely you’ll prioritize more features from the Ideal quadrant and a few from the Investing in the Vision quadrant. You’ll want to avoid what’s not a good vision fit as much as possible while being practical about survival. It’s a balance. For example, Spiro.ai, the AI CRM (artificial intelligence customer relationship management) startup, dedicates 25 percent of engineering bandwidth to work on the Investing in the Vision quadrant in each sprint.

What’s most important in this exercise is that all team members should be able to engage in this discussion and share their rationale for why a feature belongs in a particular quadrant. As individuals get comfortable sharing their rationale using the two-by-two rubric, it becomes a helpful tool for communicating your rationale for your priorities to stakeholders. This communication helps to continuously reinforce the alignment between product teams and executive leadership on the product vision.

Using the two-by-two rubric for prioritization is an easy way to bring Radical Product Thinking into your organization. Teams at any level—whether the executive leadership team or a product development team—can use it to infuse the vision into their everyday decision-making.

YOUR PRIORITIES (AND YOUR RUBRIC) MAY EVOLVE

Most likely, your rationale for priorities will change over time and you’ll find that your vision-fit-versus-survival definitions may need to evolve. Just as your vision requires periodic review to account for changing market conditions, the same applies to survival. Your biggest risk might change over time, and your rubric for decision-making should change to accommodate this evolution. If your Radical Vision Statement needs to change, it’s important to acknowledge that and communicate the new trade-offs. Every time you use the two-by-two rubric, start by restating your two axes and confirm they are still valid.

Explicitly stating your two axes is also helpful because your priorities aren’t uniform across an organization. A team working on a long-term R&D project may write a Survival Statement focused on the technological risk, whereas a team working on an existing product may define survival by financial risk.

In larger companies with multiple products, each team’s priorities are driven by that team’s specific vision and the survival risk, which may be different from those of another team. Each team should write vision and survival statements and create its own two-by-two to balance the long term against the short term.

When you’re talking to someone on a different team and draw up a two-by-two, you can pick which product’s vision fit and survival you’re referring to or you may choose to refer to the vision fit and survival axes at a company level if you’re talking about your collective priorities. The prioritization rubric is a communication tool to explain your rationale for priorities and decision-making across the company.

SIMPLICITY OVER PRECISION

The Radical Product Thinking approach to prioritization is based on a clear choice of simplicity over precision. Many companies choose to create complex spreadsheets to calculate numerical rankings for priorities. The simple two-by-two rubric is deliberately, radically different. It’s designed to develop intuition so that, like Jedis, everyone in the organization can learn to use the Force and find the right balance.

A few years ago, when I started consulting for a company to help increase alignment in the organization, product teams were using a numerical approach to prioritization and decision-making. The company culture was very analytical and data-driven and this desire for precision permeated the prioritization process. One product team showed me their painstaking work in prioritizing over 150 features: The team had picked five principles that were important for the product and scored each feature on how well it achieved a certain principle. Each of the principles had a weighting, and once the team had scored a feature against the five principles, the spreadsheet would spit out a magic number that indicated the feature’s priority from 1 to 150. The spreadsheet looked really detailed and seemed very precise.

But it turned out that this approach was giving the team a false sense of precision; no one could explain why a particular feature ranked number 57. The rationale always came back to the spreadsheet itself: “Well, this is how the feature ranked on the five principles and hence its priority.” While the team had a list of priorities, they didn’t have an intuition for making the right trade-offs; the product leader’s influence on decision-making was limited to the spreadsheet.

The magic spreadsheet approach to prioritization had another undesirable side effect: its complexity was leading to fewer prioritization discussions with stakeholders. These discussions, when they happened, often devolved into tweaking the scores and masked the more fundamental misalignments. When we switched to the RPT approach to prioritization, several leaders commented that it had become easier to understand the team’s rationale for prioritization and provide feedback.

The RPT approach to prioritization opens conversations and leads to a more facilitative approach. As a result, not only does this approach lead to more buy-in for decisions, it also leads to rich discussions that create a shared intuition in the team for decision-making.

You could spread your influence and help others develop your intuition by having others observe your decision-making without the two-by-two, but this approach takes a long time. In my workshops I often explain this with the analogy of doing algebra. Imagine you’re introducing smart students to algebra. When you show them the problem x — 1 = 0 and tell them the solution is x = 1, your students will quickly see the pattern for solving the next such problem using intuition.

But the more complex your problems and the more variables, the harder it is to see the pattern and develop intuition. When we dictate priorities top down, the obvious decisions will make intuitive sense to your team. But for the more complex scenarios, the decisions and priorities you hand down to your team may seem arbitrary. Some may see your pattern and keep up, but others may not. By using the two-by-two and explicitly discussing trade-offs, you build intuition faster in your teams and bring the whole team with you on the journey.

Your vision gives you the drive and the purpose on this journey; it’s like having a powerful engine in a car. Prioritization is like the tires—it’s where your vision meets the reality on the ground (your business needs). To build vision-driven products, you need both the power of a good vision and the ability to translate that into priorities. The RPT approach to prioritization and decision-making helps your team internalize and use your vision every day.