Rebuilding the Relationship Between Manufacturers and Retailers

In the perennial tug of war between manufacturers and retailers, retailers seem to be winning. But manufacturers can benefit by understanding what type of business model a retailer emphasizes — and tailoring their approaches accordingly.

BY NIRAJ DAWAR AND JASON STORNELLI

IN THE PERENNIAL TUG OF WAR between manufacturers and retailers, retailers seem to be winning. Just a few years ago, manufacturers had hopes of being able to manage consumer relationships and product delivery directly. But today’s retail industry is more concentrated than ever; in many industries and markets, a handful of retailers account for the majority of sales. Retailers, whether they operate traditionally or electronically, have become increasingly astute at capturing consumer loyalty with effective merchandising, innovative private-label offerings and targeted pricing and rewards programs. Their ability to control market access and influence consumer buying behavior means not only that manufacturers need retailers more than ever but also that manufacturers’ need to understand what makes retailers tick is more pressing than ever.

As retailer influence has grown, power has moved downstream in a wide range of industries, including hardware, books and consumer electronics. A prime example is the grocery industry, where global manufacturers have seen their brand clout erode in favor of consumer relationships cultivated by retailers. Manufacturers across industries rightly ascribe retailers’ power to their increasing size and concentration. For example, in 2007, Wal-Mart’s sales were approximately 4.5 times greater than those of its largest supplier, Procter & Gamble.1 Consolidation and retailers’ global scale have reduced the number of “buying points” that manufacturers can develop.2 By 2010, the 10 largest grocery retailers represented nearly 70% of U.S. sales, up from less than 30% 10 years earlier. The trade is even more concentrated within regional markets in the United States, as well as in most developed countries.3 Retailer scale has other consequences, too: It makes private-label programs viable, and it justifies the costs and effort of setting up loyalty and data-mining programs.

Recognizing retailers’ clout, manufacturers now routinely allocate two-thirds or more of their marketing budgets to trade marketing, in-store promotions and cooperative advertising rather than to cultivating their own consumer relationships through media advertising and consumer promotion.4

Trade marketing expenditures have been growing in recent years, but neither side is happy about it. Manufacturers’ attempts to influence retailer behavior have been only partially successful. They can help highlight a brand in store or bundle it with complementary products in a custom display, but these tend to deliver tactical gains, not enduring competitive advantage; they last only until competitors outbid the promotion. Ultimately, the retailers decide how the money is spent. It is clear that manufacturers need a better strategy.

Although retailers seem to have the upper hand, they are not satisfied with the current system, either. Most retailers consider manufacturer trade support to be both inadequate and insufficiently strategic.5 They have trouble converting trade promotion into profits. Rather than building longer-term partnerships with suppliers and nurturing store and shopper loyalty, they tend to compete on price and fritter away the trade support they extract from manufacturers.6

Rebuilding the Relationship

Accounts of the rocky relationship between manufacturers and retailers have mostly focused on the balance of power between them: where the power resides, why money changes hands and how the spoils are divided. However, we believe that manufacturers have the ability to rebuild this relationship by understanding the retailers’ business model. (See “About the Research.”)

ABOUT THE RESEARCH

We set out to examine if there was a better way for manufacturers and retailers to manage their fraught relationships. Our goal was to develop a prescriptive framework for manufacturers to improve the allocation of trade marketing resources, which form a significant and increasing portion of any marketing budget. Our analysis of financial reports, trade journals, case studies and the academic literature on channel and trade relationships was supplemented with in-depth interviews with retailers as well as analysts and consultants covering the retail industry.

One of our early insights was that retailers have a broader choice of business models than manufacturers do. We generated an exhaustive list of business models that retailers in the grocery industry could potentially use and then narrowed the scope of our examination to the most prevalent and distinctive models presented here.

Next, we sought evidence for both the presence and the enduring nature of those models by examining multiple years of financial statements for a globally representative sample of retailers, including some from North America, Europe and the United Kingdom. We discovered that the majority of key metrics remained stable over the period we examined, suggesting that the business models selected by retailers tend to endure over time.

Finally, we identified a set of prototypical retailers for each business model by conducting an analysis of the financial filings, company statements, financial analyst reports and trade and popular press reports. The retailers detailed here represent clear exemplars of the four business models that we identified. Based on this analysis, we constructed a prescriptive framework.

Our findings reveal the importance of trade segmentation on multiple levels. We argue that manufacturers should segment their channel partners according to business model, enabling them to pursue differentiated strategies at the bargaining table. Although our findings and recommendations are applicable in many settings, we examined the grocery industry as a model for this approach because of its size and because it represents a bellwether for channel relationships in many other industries.

Retailers have different ways of making money: encouraging customer loyalty, building profitable private labels, relying on financing from suppliers or keeping overhead low. As companies such as Tesco in the United Kingdom, Loblaw in Canada, and U.S.-based Costco and Wal-Mart have shown, multiple strategies are available, but retailers tend to choose one (or in some cases, two) that they emphasize. The particular approach, or mixture of approaches, that retailers select defines their business model and differentiates them from competitors. Manufacturers, by contrast, have much less flexibility; they are locked into large fixed investments and wedded to products and brands with long payback cycles. Like it or not, they need to sell their products through retailers. Expectations of direct sales to consumers through the Internet have not panned out for most manufacturers, because many consumers like to compare products from multiple sellers.

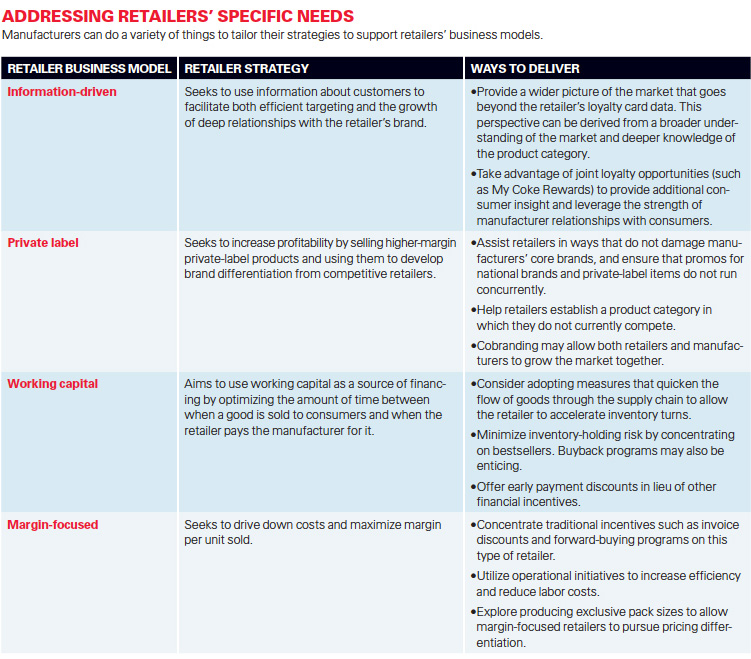

ADDRESSING RETAILERS’ SPECIFIC NEEDS

Manufacturers can do a variety of things to tailor their strategies to support retailers’ business models.

Retailer Business Models What can manufacturers do to improve their power positions, align their efforts with the strengths and objectives of the retailers and better reach their target consumer? We examine four different retail models: Tesco, which excels at connecting with consumers through its loyalty program; Loblaw, which exemplifies relying heavily on private labels; Costco, which gets its suppliers to finance its inventory; and Wal-Mart, which focuses closely on margins. After describing the models, we will recommend tailored strategies manufacturers can pursue. (See “Addressing Retailers’ Specific Needs.”)

The Information Model

Perhaps the largest change in the grocery retail industry during the past 30 years has been the explosion of consumer data. Accurate, real-time and actionable consumer information is particularly important in the consumer packaged-goods trade because of the frequency of consumer visits and fast movement of goods. In recent years, some retailers, including Kroger and Tesco, have seized opportunities to jump ahead of their competitors by connecting information about transactions with information about individual consumers, thereby enabling them to know who buys what when, and at what price. Armed with these insights, they can streamline their sourcing and inventory, target their communications and make their promotions much more efficient.

In a market where competitors are heavily oriented toward private labels, Tesco’s Clubcard program isn’t just a vehicle for getting customers in the door; it’s designed to build a long-term “loyalty contract” in which the consumer receives rewards but also gives Tesco information that enables highly targeted promotions and communications.7 Consumers cite the Clubcard program as the No. 1 reason they want Tesco rather than a competitor to open a store in their neighborhood and as the leading driver behind their decision to switch to Tesco for their regular shopping.8

How powerful is Tesco’s Clubcard program? In the early 1990s, Tesco was the United Kingdom’s No. 2 supermarket behind Sainsbury’s. In the year and a half after Clubcard was launched, Tesco gained and held the top spot, increasing sales by 28% at a time when Sainsbury’s revenues fell 16% and it tried to create its own loyalty program.9 Clubcard was probably not the only reason for Tesco’s rise, but for retailers it demonstrated the power of data. Later in the decade, Tesco fought off Wal-Mart, which entered the U.K. market with its purchase of Asda. Instead of trying to compete with Asda across the board on price, Tesco, drawing on Clubcard data, focused on a short list of products (including margarine) that influenced customer price perceptions and slashed prices on those items. By doing so, it was able to retain price-sensitive consumers while maintaining its margins on other products.10

Tesco also uses Clubcard to expand the range of goods customers put in their cart. The company noticed, for example, that new parents often shopped for baby products at Boots, a large pharmacy chain, and that they were willing to pay premium prices because they received helpful advice. Tesco countered with Baby Club, now the Baby & Toddler Club, which leverages the Clubcard infrastructure to give parents helpful and timely information while also providing discounts on baby products. In the first two years, Tesco grew its share of the U.K. baby market by 24%, and it had signed up 37% of parents-to-be as members.11

Tesco’s proficiency with consumer information has allowed it to fend off competitors and target new segments. Though Tesco is strong in many areas — for example, the company also has a high level of private-label sales — its ability to understand and target individual consumers is so well recognized that it now sells its loyalty know-how to other retailers through its dunnhumby subsidiary.12

Building relationships Given the demonstrated benefits Tesco derives from consumer information, why don’t other retailers attempt to follow this model? The reality is that many retailers either aren’t willing or aren’t able to invest the resources to turn shopper data into insight. Some treat loyalty programs as a discount-delivery vehicle rather than as a means of building relationships.

Despite the current hype about big data, in industries such as retail where such data have been available for a number of years, loyalty programs have had an unremarkable record. A 2010 survey by the Chief Marketing Officer (CMO) Council, a marketing industry group, found that 51% of consumers were dissatisfied with their loyalty program memberships. The average consumer belongs to 14.1 loyalty programs but is only active in 6.2 programs. Marketers were even unhappier: only 14% of loyalty program managers reported that they were productively using insights gained from consumer data.13 In 2007, Boise, Idaho-based Albertsons dropped its Preferred Card program in many U.S. markets, and others have done likewise.14

A bigger picture We see a big opportunity for manufacturers. Many manufacturers have experience that can help retailers use information more effectively. For instance, although retailers have access to scanner data that tells them what products consumers buy, their perspective is often limited to the activity in their own stores. Suppliers see a much bigger picture, since they usually sell to other retailers. Thanks to this perspective, they can demonstrate — with data — the effectiveness of new practices that retailers might otherwise not consider. These practices can be profitable for both the retailer and the manufacturer.

Even within their own stores, retailers tend to know little about consumer behavior before the consumer checks out. Vendors act as category captains in many instances, advising grocers on shelf space placement and inventory tracking. For example, Kraft Foods works with retailers on long-term studies of product organization within the dairy case, sometimes resulting in double-digit sales gains for the retailer. It also establishes cooperative funding programs to develop joint merchandising initiatives that have proven successful elsewhere.15

Finally, manufacturers with brands that have strong equity have opportunities to construct their own loyalty programs and use them collaboratively with retailers. For example, Coca-Cola used its My Coke Rewards program in 2009 to build consumer connections while simultaneously offering bonus points to Safeway.com delivery customers.16

The Private-Label Model

For more than three decades, the market share for private labels has been growing at a steady pace. More than half of the respondents to a 2010 survey said private-label products offer superior value at a lower price, and nearly 70% considered them when shopping for premium items.17 Not surprisingly, retailers like private labels for their higher margins and consumer pull.

Consider Loblaw, Canada’s largest food retailer and a major seller of general merchandise in North America. Loblaw’s President’s Choice and No Name brands are the No. 1 and No. 2 packaged goods brands in Canada.18 There is ample evidence to show that private labels drive innovation and growth. To provide value to retailers like Loblaw, manufacturers must find ways to innovate both at the product level and at the category level. This requires re-examining their brand’s place in the category.

Private label–focused grocers such as Loblaw manage multitiered programs that span the price/quality range within a category: Loblaw’s No Name brand occupies the value-priced position, while President’s Choice aims to match or beat the top national brand. For premium brands, however, maintaining innovation and product quality is essential. Campbell Soup, for example, has introduced portable microwavable soup packaging to appeal to people on the go. Such innovation by leading brands is beneficial to participants across the product category. For grocers with well-established private label programs, too much private-label activity can be harmful; national brands drive traffic, and when store-brand penetration gets too high, consumers may begin to defect.19

Innovative partnering Manufacturers should think about partnering with retailers to produce private-label products. In addition to the obvious volume and capacity utilization gained from producing private labels, there are more subtle benefits, such as acquiring a better understanding of the category and obtaining leverage over private labels. Vendors that manufacture private labels can encourage the retailer to position the private label to compete with other national brands and differentiate their own products with distinctive packaging, product sizes and quantities.

Many manufacturers worry that their branded-goods business will be overwhelmed by private labels if they produce their own private-label entry. But strategies for protecting core brands have been evolving. H.J. Heinz, for instance, produces private-label products in a number of categories where it also sells national brands, with the exception of ketchup.20 Different brands play distinct roles on the grocery shelf; the Heinz products and the retailer’s items don’t always compete head-to-head. Depending on the circumstances, they can appeal to consumers in different ways and can be promoted at different times.

Cobranding opportunities Retailers are beginning to offer cobranded products, in which national brands are an element in a store-brand product.21 Safeway, for example, offers Safeway Select ice cream containing pieces of Nestlé’s Butterfinger candy, with the Butterfinger name prominently featured on the packaging. With cobranding, the retailer benefits by bolstering its claims to uniqueness or quality; the national brand gets to promote its brand.

Retailers focusing on private labels are also attempting to broaden their offerings into largely uncharted territory, including ethnic foods, nutritional supplements, organics and environmentally friendly items. Here, manufacturers with extensive category knowledge can make real contributions. They can often draw upon experience gained from across the globe, allowing retailers to be more regionally focused.

For manufacturers, some of the most promising opportunities may come from no-frills retailers such as Aldi, Dollar General and Family Dollar, which are focused on private labels but seek to drive traffic with branded goods. For example, Aldi, based in Germany but with more than 1,000 stores in the United States, has found that it must carry branded goods such as Colgate toothpaste and Ferrero chocolates to satisfy shoppers.22 A study of European discounters found that there are three ways that national brand manufacturers and discount retailers can cooperate profitably.23 First, the price differential between the national brand and the private label must reflect the perceived quality difference. Second, the price of national brands at the discount store needs to be lower than at mainstream retailers. And third, because discounters frequently offer products in large quantities, manufacturers should invest in packaging and case designs.

The Working Capital Model

Cash flow is critically important to the retailer. All retailers focus on the efficient use of working capital, but for successful players like Costco, it is a pillar of their strategy. Manufacturers have an opportunity to design programs to meet the working capital needs of retailers and to focus these programs on those retailers most concerned with working capital efficiency.

Manufacturers should look for two simple clues. First, does the retailer have a working capital gap — does it sell goods faster than it pays for them? And second, is this gap the result of efficient operations or delayed payments to suppliers?

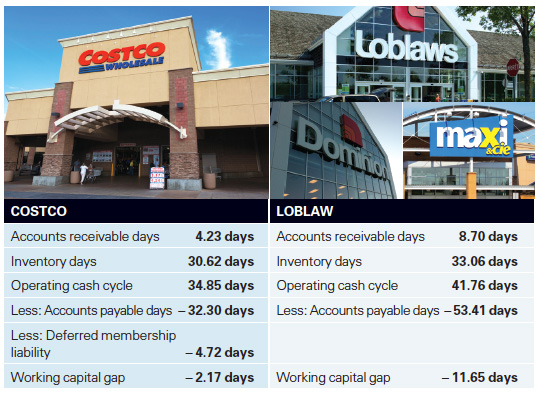

A negative working capital gap can be a significant competitive advantage. Our analysis suggests that while negative working capital gaps are common, their size varies across retailers. To illustrate the differences, let’s compare Costco, the large U.S. warehouse-club retailer, and Loblaw. (See “Analyzing the Working Capital Gap.”)

ANALYZING THE WORKING CAPITAL GAP

A working capital gap analysis compares accounts-receivable days, inventory days and accounts payable to establish the cycle of inventory holdings and cash inflows versus cash payments. The ideal situation for a retailer is to have a negative gap — to sell products faster than they are paid for. Our analysis suggests that while negative working capital gaps are common, their size varies across retailers. To illustrate the differences, let’s compare Costco and Loblaw.

At first glance, the discrepancies in working capital efficiency appear small and suggest that Loblaw is more efficient than Costco. But because its operations require less operating cash (and because it gets working capital from membership fees), Costco pays its suppliers more than 20 days faster than Loblaw. This allows Costco not only to finance its operations with vendors’ cash but also to pay vendors quickly enough to capture early payment discounts.

SOURCE: ThomsonONE, 2010. Used with permission of ThomsonONEi. The method of analysis is adapted from J. Mullins and R. Komisar, “Getting to Plan B: Breaking Through to a Better Business Model” (Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review Press, 2009).

Faster selling cycles At first glance, the discrepancies in working capital efficiency appear small, and they even suggest that Loblaw is more efficient than Costco. Loblaw has a gap of -11.65 days (during which suppliers provide financing for inventory), compared with Costco’s gap of only -2.17 days. However, significant differences emerge when the different components are considered individually. First, Costco collects receivables twice as fast as Loblaw; its receivables are outstanding for 4.23 days versus Loblaw’s 8.7 days. Second, Costco turns its inventory faster than Loblaw. Although mattresses typically take much longer to sell than milk, Costco manages to push its stock out the door quickly. The result: Costco requires nearly one week less of working capital to operate than Loblaw does. Also note how quickly Costco pays suppliers. Because its operations require less operating cash (and because it gets working capital from membership fees), Costco pays its suppliers more than 20 days faster than Loblaw does. This allows the company to finance its operations with vendors’ cash while also paying vendors quickly enough to capture early payment discounts. Costco’s strategy is no accident. Rather, it’s a core component of its operating philosophy.24

Manufacturers have an opportunity to design programs to meet the working capital needs of retailers and to focus these programs on those retailers most concerned with working capital efficiency.

Payment flexibility Retailers that manage working capital well carry merchandise that sells quickly. For example, Costco stores typically carry fewer than 4,000 stock keeping units, or unique products, a small fraction of what most supermarkets and hypermarkets carry.25 Every retailer worries about being stuck with inventory that won’t sell in a timely manner. Manufacturers are well-positioned to provide retailers with market intelligence, sales guidance and buyback programs. Manufacturers can also consider developing exclusive items or assuring retailing companies that they will be the first to receive new products.

Selling to retailers focused on managing working capital is not easy; it requires both financial and inventory efficiency. But developing smart programs to fit the retailers’ need for quick stock movement and payment flexibility can yield significant dividends.

The Margin Model

Of the four retail business models we studied, margin retailers present the thorniest issues for manufacturers. Since the cost of goods sold (COGS) is the retailer’s biggest cost, those focused on margins typically are relentless in their efforts to drive this cost down, even if it means brutal negotiations with their suppliers.

No retailer is better known for its focus on margins than Wal-Mart. Wal-Mart’s global sourcing initiatives have cut intermediaries and dramatically reduced costs for categories like perishables, leading to significant retail price cuts.26 As a result, it has maintained a favorable COGS-to-sales ratio (approximately 75% of sales) over the past five years, despite its intense focus on everyday low pricing. Wal-Mart’s cost diligence has paid off even as it has grown. Operating costs have remained between 18% and 19%, and net margins have topped 3% over the past five years.

Beyond incentive programs How can suppliers end up on the right side of the cost equation for margin-focused retailers such as Wal-Mart? Incentive programs like invoice discounts, early payment enticements and forward buys are costly, but suppliers may need to offer them strategically; they may be critical to building dominant market share positions.27 Manufacturers should also take advantage of other tools for building close relationships with retailers, including package design and logistics that minimize handling costs and transit time. For instance, Wal-Mart requests that poultry vendors pack trays of chicken in uniform weights to eliminate the need to individually price them in-store.28 Similarly, suppliers can redesign packaging to make it easier for stores to display products and make them more attractive to consumers.29

Although making exclusive products and packages may add to a manufacturer’s costs, they can help margin-focused retailers differentiate their products and improve their pricing power. Nestlé, for example, offers the Germany-based discounter Lidl custom two-liter containers of its Vittel mineral water. Lidl is able to sell the product for significantly less than competing retailers. Nestlé, for its part, is able to boost its margins because higher product volumes allow for more efficient distribution and manufacturing, thereby lowering costs.30

The grocery business is challenging for both manufacturers and retailers. With extremely thin margins, fierce competition both between suppliers and between stores, and rapid change, there are incentives for retailers and manufacturers to find ways to cooperate. When manufacturers work with retailers to optimize shelf layouts, or when retailers approach manufacturers to reach specific consumer segments, they both gain by moving more volume and appealing to more consumers. Manufacturers can enhance their competitive positions by stepping back from harried relationships and intense negotiations to rethink their strategies toward retailers. We suggest that manufacturers tailor their strategies to retailers’ specific business models. The four models described here provide a framework that manufacturers can use, and the lessons from the consumer packaged goods industry can be adapted to other manufacturer-retailer relationships.

Niraj Dawar is a professor of marketing at Western University’s Richard Ivey School of Business in London, Ontario, Canada. Jason Stornelli is a doctoral candidate at the Stephen M. Ross School of Business at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Comment on this article at http://sloanreview.mit.edu/x/54218, or contact the authors at [email protected].

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to thank ECR Europe’s International Commerce Institute for funding that supported this research.

REFERENCES

1. Wal-Mart, “2007 Annual Report” (Bentonville, Arkansas: Wal-Mart, 2007); and Procter & Gamble, “Designed to Grow: 2007 Annual Report” (Cincinnati, Ohio: Procter & Gamble, 2007).

2. D.A. Griffith and R.F. Krampf, “Emerging Trends in U.S. Retailing,” Long Range Planning 30, no. 6 (1997): 847-852; L.W. Stern and B.A. Weitz, “The Revolution in Distribution: Challenges and Opportunities,” Long-Range Planning 30, no. 6 (1997): 823-829; and N. Wrigley, “The Landscape of Pan-European Food Retail Consolidation,” International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 30, no. 2 (2002): 81-91.

3. E. Ogbonna and B. Wilkinson, “Power Relations in the U.K. Grocery Supply Chain: Developments in the 1990s,” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 5, no. 2 (April 1998): 77-86.

4. A.C. Nielsen, “Trade Promotion Practices, 16th ed.” (2007), 20.

5. A.C. Nielsen, “Trade Promotion Practices, 16th ed.” (2007), 18; and L. Moses, “Trade Promotion Better; Frustration Remains,” Supermarket News, March 21, 2005, 51.

6. S.Y. Kim and R. Staelin, “Manufacturer Allowances and Retailer Pass-Through Rates in a Competitive Environment,” Marketing Science 18, no. 1 (winter 1999): 59-76; K.L. Ailawadi, “The Retail Power-Performance Conundrum: What Have We Learned?” Journal of Retailing 77, no. 3 (2001): 299-318; and M. Corstjens and R. Steele, “An International Empirical Analysis of the Performance of Manufacturers and Retailers,” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 15, no. 3 (May 2008): 224-236.

7. C. Humby, T. Hunt and T. Phillips, “Scoring Points: How Tesco Continues to Win Customer Loyalty” (London: Kogan Page, 2004), 69.

8. Tesco, “Annual Report and Financial Statements 2011” (Hertfordshire, U.K. http://ar2011.tescoplc.com/business-review/growing-the-uk-core.html).

9. Humby, Hunt and Phillips, “Scoring Points,” 68.

10. Ibid., 273.

11. C. Murray, “The Marketing Gurus: Lessons from the Best Marketing Books of All Time” (New York: Portfolio, 2006).

12. Tesco, “Annual Report.”

13. “The Leaders in Loyalty: Feeling the Love From the Loyalty Clubs,” white paper, CMO Council, Palo Alto, California, 2010, pp. 3, 8, 11.

14. “Loyalty Programs: Mining for Gold in a Mountain of Data,” Aug. 1, 2007, http://knowledge.wpcarey.asu.edu; and Humby, Hunt and Phillips, “Scoring Points,” 79.

15. N. Kumar, “The Power of Trust in Manufacturer-Retailer Relationships,” Harvard Business Review 74 (November-December 1996): 92-106.

16. http://shop.safeway.com/content/touts/landingpages/22_mcr_landing.asp.

17. “Survey: Canadians High on Store Brands,” Private Label Store Brands, Aug. 1, 2010, 7.

18. Loblaw, “Balancing Act: Loblaw Companies Limited 2009 Annual Report” (Brampton, Canada: Loblaw), 4.

19. S.K. Dhar and S.J. Hoch, “Why Store Brand Penetration Varies by Retailer,” Marketing Science 16, no. 3 (1997): 208-227; and K.L. Ailawadi, K. Pauwels, & J.-B.E.M. Steenkamp, “Private-Label Use and Store Loyalty,” Journal of Marketing 72 (November 2008): 19-30.

20. D. Dunne and C. Narasimhan, “The New Appeal of Private Labels,” Harvard Business Review 77 (May-June 1999): 41-52.

21. R. Vaidyanathan and P. Aggarwal, “Strategic Brand Alliances: Implications of Ingredient Branding for National and Private Label Brands,” Journal of Product & Brand Management 9, no. 4 (2000): 214-228.

22. S. Clifford, “Where Wal-Mart Failed, Aldi Succeeds,” New York Times, New York edition, March 30, 2011, p. B1; and B. Deelersnyder, M.G. Dekimpe, J-B.E.M. Steenkamp and O. Koll, “Win-Win Strategies at Discount Stores,” ERIM Report Series ERS-2005-050-MKT (Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Erasmus Research Institute of Management, 2005).

23. Deleersnyder et al., “Win-Win Strategies.”

24. Costco Wholesale, “Annual Report 2010” (Issaquah, Washington: Costco Wholesale), p. 8.

25. Costco, “Annual Report 2010,” p. 9.

26. Thomson Reuters, “Wal-Mart Stores Inc. Analyst and Investor Webcast,” (June 4, 2010): 6, available http://media.corporate-ir.net/media_files/irol/11/112761/Transcripts/Analysts_meeting2010-06-04.pdf.

27. P.N. Bloom and V.G. Perry, “Retailer Power and Supplier Welfare: The Case of Wal-Mart,” Journal of Retailing 77 (2001): 379-396.

28. P. Callahan and A. Zimmerman, “Wal-Mart Tops Grocery List with Its Supercenter Format,” Wall Street Journal, May 27, 2003.

29. Deelersnyder et al., “Win-Win Strategies.” This method is adapted from J. Mullins and R. Komisar, “Getting to Plan B: Breaking Through to a Better Business Model” (Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review Press, 2009).

30. N. Kumar and J.-B.E.M. Steenkamp, “Private Label Strategy: How to Meet the Store Brand Challenge” (Boston: Harvard Business Review Press, 2007).

i. ThomsonONE (New York, NY: Thomson Reuters) www.thomsonone.com.

Reprint 54218.

Copyright © Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2012. All rights reserved.