Chapter Three

The Studio Setup

The best recordings come from properly designed spaces. Before anything is loaded into the room, before any equipment setup begins, you must determine the best ways to take advantage of the recording space. Some studios have dead areas and live areas, each with their individual functions. Some studios have adjustable wall panels that can liven or deaden areas of the room. As you learn the studio’s live and dead areas, you can better decide to, for example, record horns in a live area of the room and record an intimate acoustic guitar in a less live area.

Use your understanding of the physical limitations and characteristics of the room to help decide where each setup will sound best.

Room Preparation

- Clean the place. A clean studio, as with a clean control room, keeps everyone from getting anxious. It makes you look like a professional, not some hack that doesn’t care enough to clean out the dirty food containers.

- Use it or lose it. Remove everything that isn’t involved in your session, such as another client’s equipment. It’s not a storage room. Every item in the room rattles, so if it isn’t there, that’s one less rattle to worry about. As well, when the client books the studio, he wants the whole studio. It isn’t fair to him when you store someone else’s equipment in the corner of the room.

- Go ahead and ask. In an unfamiliar studio, ask a staff member about any standard instrument placements. Then use that information, along with your experience, when placing each instrument. Sketch the layout of the studio and use it to decide where each instrument will go.

- Deal with noisy floors and chairs. Oil squeaky chairs and throw down a carpet over squeaky floors. Everyday noises that are unconsciously blocked out by our ears are not blocked out by the microphones.

- Diffuse the situation. Use diffusion devices, such as sections of acoustic foam, stand-alone baffles, perhaps sections of plywood placed on the floor to fit your specific session needs. Figure 3.1 shows how properly placed baffles will block and absorb most initial reflections. In this instance, reflections coming back off the wall are not an issue. Baffles might be used as absorption devices or reflective devices, depending on the situation. Note that absorption devices do not affect some frequencies, such as low lows.

- Use various soft and hard surfaces aimed in different directions. The original Little Mountain Studios in Vancouver had plywood-covered cupboard-style doors that, when opened wide, contained acoustic absorption foam. Room sound could be absorbed, creating a deader sound, or diffused or reflected, resulting in a live sound, all depending on the particular needs of the session.

- Any size recording studio can make hit records. Good equipment means nothing unless the players are up to the task. Thinking you will get a great recording because you use the best gear is like thinking you can do a great painting because you have the best paintbrushes. Even a broken pencil can draw a masterpiece.

Placement

- Draw a setup sheet with the layout of the room. Before considering where the instruments and players are placed, draw an instrument setup sheet, along with an input list to refer to. This helps when other people are helping to set up the room with you.

- Places, please. Most musicians, if they have been playing together for a long time, get used to certain placement among the rest of the players. Maybe the rhythm guitar player prefers to stand on the left side, while the bassist may like the right. Ask the players if they are used to playing in specific locations in reference to each other, and set them up that way.

- How many players are recording basic tracks? Most recordings are broken down into three sections: basics, also called bed tracks, then overdubs and mixing. In today’s studio, these overlap considerably. Determine how many players will be in the studio during the basics to properly choose which, and how many microphones to use on each setup. Different situations will require different approaches.

- What is the style of music? Determine player placement by using the style of music, how prominent each instrument will be, and how many players there are. Is it:

- A jingle? Jingles are advertisements heard on radio and television—often 30 or 60 seconds long. Recording will often be completed in a single day so there will not be a lot of time for experimentation. The most important factor here is usually the time restraints. Because the musicians that play on jingles are professionals, they will most likely play the part properly every time. The emphasis here is not on setup or performance. It is assumed that the setup is good and the performance will be fine. The important factors here are time and money. Set up and press record. Proper documentation is key for a smooth running jingle session. Many different versions of a commercial or ‘spot’ are recorded, and each spot needs proper documentation during recording, editing, and mixing.

- A film soundtrack? As films and movies get cheaper and more accessible, more engineers are recording soundtracks. While most modern records are recorded to feature vocals or a certain instrument, movie soundtracks are less focused on the individual player and more on creating a feel that complements the movie. There is no strict standard, and you would record what each scene requires, whether a large group of players or an individual musician. As well, you must deal with ‘movie’ people.

- A power rock band? They might sound better in a larger live space. Start the session by concentrating on bass and drums, but also record reference vocals and guitars.

- A jazz session? You may prefer a mellower, drier feel from a less reverberant space. With jazz, often players will want to watch each other without headphones. Everything is recorded live with no overdubs and never a click track. Confirm that your session has enough hard drive space, because left to their own devices, jazz players will never stop playing. Sleep? Food? Time itself? All secondary to the groove.

- A demo? Recording demos is not the time to spend four hours getting that perfect guitar sound. Take less time on setup, and more time recording.

- A television show? Many televisions have smaller speakers that cannot recreate a wide range of frequencies. Therefore, a piano, for example, recorded for a television soundtrack might not have the same equalizer setting as a piano recording for a rock record because on a television soundtrack, boosting low, low frequencies might not have much of an effect. They will equalize and compress it at the TV station.

- A rap or hip-hop session? Commonly electronic drum machines and modern keyboards combine with live vocalists. Vocals might be recorded after all the music is recorded. To play off of each other, sometimes two or more singers record into separate microphones at the same time.

- An independent punk band? They might sound best in a smaller, tighter ‘garage’ style room. You won’t have a lot of setup time, and will often record raw sounds, with minimal time for a studied vocal track.

- A solo acoustic player/singer? Setup may sound best in a smaller more intimate space, and the voice and the musical instrument might have separate microphones. Maybe the microphones will be placed in a stereo array in front of her, as long as she is comfortable.

- A polka band? They will probably all be in one room, with no headphones and all playing together, as most polka bands do.

- No matter what the situation, all aspects of the recording, production and playing must be of the highest quality. The world (hopefully) is going to hear the results, so take the time to set up properly and record everything correctly.

- Don’t isolate the players. Just because an amplifier is isolated doesn’t mean that the player must be isolated as well. Commonly, players being recorded together should be able to see each other, and at least one should be able to see the engineer. The person who can see the engineer normally gets a talkback microphone.

- Carpets and chairs. Before setting up the microphone stands and running the cables, lay out any carpets that will be needed. Tape them to the floor to keep them in place and so no one trips and falls. Once the carpets are down, place chairs for each player. They might not use them when they are actually playing, but they may want to sit down during playback, or during a lull in a long session.

- Set up and sit down. Bring in and set up the instruments as described in the next few chapters. With the instruments placed according to your setup sheet, begin placing the microphone stands and cables.

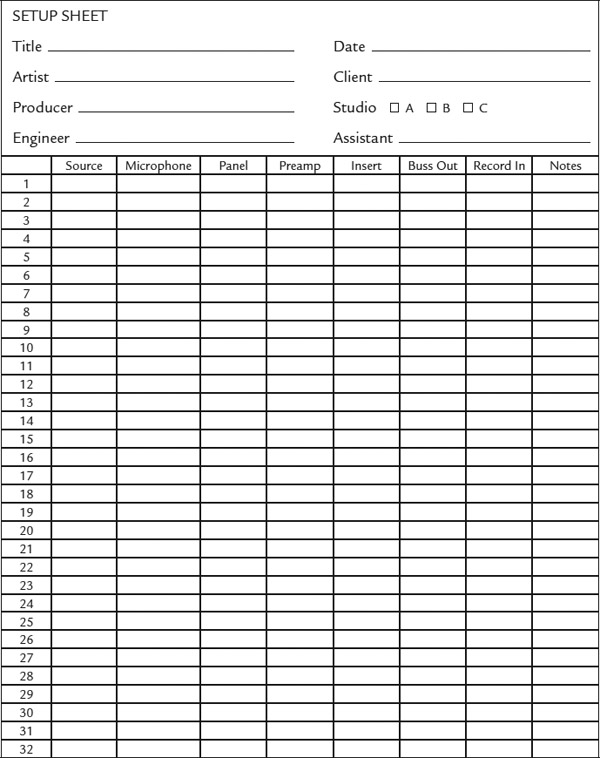

- What is a setup sheet? The setup sheet is a page that the engineer fills in for a visual representation of all the microphones, inputs, and signal routing. Figure 3.2 shows sections that include:

- Source: Instrument, amplifier, vocal, or whatever sound is being recorded.

- Microphone: Obviously what brand and model number. Perhaps even a specific microphone’s serial number.

- Panel: What input the microphone is plugged into at the studio input panel. Perhaps the microphone in panel input 8 needs to route to input 10 before it reaches the pre-amps.

- Microphone Pre-amp: Maybe some tracks need to use an outboard pre-amp rather than the console pre-amps.

- Insert: This is used when a piece of outboard gear is introduced into the signal chain.

- Buss out: Used when more than one channel is being combined to fewer tracks, for example when two snare drum microphones are recorded on a single track. Both channels would be bussed to, for example buss 3.

- Record Input: This is the track to be recorded on. Perhaps you need to record the output of buss 3 onto track 20.

- The setup sheet comes in handy when a few people are helping with the setup.

Microphone Stands

- Use a boom stand. There is no situation where a microphone is left hanging from the cable or sitting on a pillow because there is no boom stand. Take the time to get a proper boom stand. Microphone placement is a cornerstone of good recording. This is the time to put your foot down. Do it right.

- Use a large boomstand. Larger boomstands tend to be more stable, with less resonances and rattles, and they help eliminate rumble from the floor.

- Don’t use a large boomstand. Microphone stands can range from a small stand to hold a tiny microphone, all the way up to a large boom with a big microphone hanging off of the end of it. Sometimes a smaller boomstand will be less obtrusive. Match the stand size with the situation.

- Stand still, laddie. Today’s microphone stands tend to be flimsy, so don’t force any of the clasps. Take the time to unscrew the fastener, set the stand and the arm to the proper placement, and then tighten the clasp. Not Superman tight, but tight enough so the microphone stays at the right spot until the end of the session.

- Duct tape rules. Leave a couple of rolls of duct tape around, but only use it to stop resonance and rattles, not to hold a microphone stand. Duct tape won’t hold a microphone stand in place for long, and it looks unprofessional. But sometimes there is no choice. If you must use duct tape to hold anything, don’t wrap a whole roll around the microphone stand. A few times around will do.

- Stand up. Place all stands and run all cables before attaching the microphone to the stand. Wheeling large boomstands around a cluttered room with a microphone connected to it is just asking for damage. Make a habit of setting up microphones last, and breaking them down first.

- Secure the boomstand. If you must use a smaller tripod boomstand, place the stand so one leg is directly under the boom, then sandbag the other two legs to keep them secure. Place a sandbag on the base of the stand to ensure stability. If someone bumps into it and it topples over, it’s your fault.

- Pair of matching shocks. When setting up to record something in stereo, use matching shockmounts, stands, and microphones. This not only looks professional, but also makes both microphones sound alike. If one microphone has a shockmount, and the other doesn’t, a slight rumble may creep into the one without the shockmount. Then you might need to add a low-end roll-off to one side, thus changing the intended matched sound.

- Weight for the boom. Set the counterweight of larger boomstands high enough so no one hits their head. If someone gets smacked in the nose, it gives the studio a black eye.

Cables

Today’s studio has a combination of analog and digital cables. The main analog cables are balanced and unbalanced, used to carry either microphone level, line level, or instrument level.

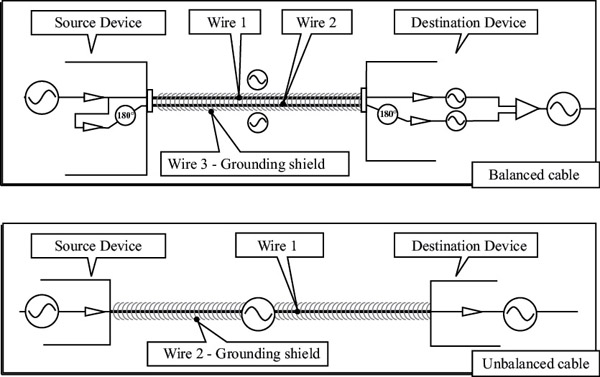

- What are balanced cables? A standard recording studio XLR balanced cable uses three wires—two to carry the signal and one for the shield. The three wires are termed hot, cold, and common. Both XLR and 1/4″ stereo cables are balanced. On a balanced 1/4″ cable the three wires connected are tip, ring, and sleeve (TRS), with the sleeve being the shield terminal.

- Figure 3.3 shows the two ends that carry the signal, and one has the polarity (phase) switched. Why? Any interference will affect both wires equally. At the balanced input connector, these equal and opposite interference signals will cancel out. This process is called ‘balancing’ or common mode rejection. This eliminates interference so you can use longer cables with minimal hum pickup.

- What are unbalanced cables? A standard guitar cord is an example of an unbalanced cable. It contains two wires—one wire is the hot, and the other is the shield. The shield is wrapped around the hot wire and used for the return signal. Unbalanced cables are normally used for getting mono signal from the instrument to the amplifier or direct box. Most outboard equipment uses 1/4″ inputs, and all consoles have the option of balanced and unbalanced 1/4″ (line level) inputs.

- Another unbalanced line is a 1/4″ nonshielded speaker cable, which is two heavy-gauge parallel wires. Cables from amplifier to speaker must be heavy gauge for as little power loss as possible. Don’t use speaker cable in place of shielded cable.

- What is microphone level versus line level? The main analog cables that are most common in the studio carry three levels of audio signal. These are:

- Line level (balanced) is the standard signal strength used in pro level gear. There is a switch on the input section of each channel of the console allowing the user to choose whether the incoming signal is line level or microphone level.

- Microphone level (balanced) is plugged into the console with the channel switched to microphone level, which activates the pre-amp, raising the level to line level.

- Instrument level (unbalanced) is the level of the signal coming out of the instrument, such as a guitar, and is boosted to line level using a direct box.

- What is a direct box? A direct box is a device that bumps microphone level to line level before it reaches the console input. The ‘D.I. box’ changes an electric instrument’s high-impedance unbalanced output signal to a low-impedance balanced signal that will properly interface with the microphone pre-amp. Some direct boxes are designed with an input pad and a ground switch on them. Like microphones and amplifiers, they vary widely in sound. Direct boxes are available as passive (transformer only) or active (pre-amp and transformer) where amplification raises the level to improve signal-to-noise ratio. Passive direct boxes might sound more natural than active ones due to lack of additional processing, but active boxes may have better frequency response.

- Advantages of using a direct box include the absence of leakage, no amplifier distortion, and a full clean sound. A good direct box records the full spectrum of the instrument, where a microphone in front of an amplifier may not. Many engineers agree that a direct box alone just can’t recreate that chest-cavity vibrating thump that an amplifier and microphone can deliver.

Running Cables

- Got cables? Confirm that there is enough cables, including 1/4″, XLR, USB cables, power cables, and AC power boxes. Bring them into the room and set them in their appropriate place.

- Use the proper cable and connectors. Adapters will always degrade the signal, so use them as a last resort. For the best results, use the proper cables so no adapters are necessary. One long cable is better than joining two short ones together.

- Respect the studio cables. Wrap and unwrap studio cables correctly and don’t throw them around. Avoid any sort of sticky tape to hold cables together. Use a specific plastic clip, a Velcro strip, or even a piece of rope with a loop on the end.

- Label the cable. Label both ends of XLR cables for easier tracing. For example, if cable 28 is connected to a microphone that is not working, rather than having to trace it through the labyrinth of all the other cables, simply read the number on the cable, then check where the corresponding number is plugged in at the input panel.

- Some studios use colored cables for different lengths, such as orange for 25 feet, blue for 50 feet etc. Use this to your advantage when setting up a large session to avoid having to double up on short cables when you run low.

- Keep it short. Use the shortest unbalanced high-impedance cables as possible. Longer cables can pick up hum and, as length increases, can diminish high frequencies.

- Keep it long. Allow enough length so cables are never taut. Don’t wrap them up in a coil, just leave the excess cable on the floor by the base of the microphone stand, in case you need to move the microphone and stand to a new location.

- Leave a channel or two open when plugging in the drums. You want all the drum microphones to enter the console in the same area. Later in the session, if you need to add another drum microphone for any reason, you won’t need to return it somewhere else on the console.

- Use the best cable. Don’t use a suspect cable on a microphone. If you’re short on cables, use it on headphones. If the cable fails during the session, the recording will not be compromised. No one wants to find out half the piano sound is gone when it comes time to mix. Remove faulty cables from the room so no one mistakes them for usable cables.

- Untie any knots in the cables. This is just good practice, eliminates any minor induction issues and looks professional, especially when you have to trace a cable across a floor covered with cables, or need to quickly wrap or unwrap a cable.

- For best results. Use the shortest, thickest, highest quality cables on the vocal microphone.

- Check your shorts. Keep an ohmmeter close by to determine where a problem lies. Is the microphone not working? Is there a short in the cable? Maybe it can be as simple as a wrong button pressed at the console. A meter tells you instantly if signal is correctly flowing through a piece of gear.

- Three cord rock and roll. Place extra everything close by. The session should never stop due to a lack of workable cables.

- Learn to solder. Anyone with experience and ability to do basic studio maintenance, such as cable repair, will be a valuable asset to any recording studio, and it is almost a necessity for home studio users.

- Power arrangers. Don’t run (high-level) AC power cables parallel with (low-level) audio signal cables. Cross power cables at right angles from signal cables to minimize AC buzz leaking into the microphone cables.

- The wall of sound. To avoid interference, run cables a few inches away from the studio wall. Right behind this wall is a plethora of power cables and other audio lines.

- Don’t plug everything into one AC outlet. You will have a hot, smoking studio with scorching leads and blazing tracks that smolder! Get it?

- Wrap the cable around the stand. If you are sure the microphone stand is properly placed and the signal flow is correct, maybe wrap the cable around the stand to keep it out of the way.

- Don’t wrap the cable around the stand. Unwrapping and removing a cable because the placement is wrong is a waste of valuable setup time. Sometimes, just leave it to hang.

- Neat, tidy, and organized. You job will be so much easier by being organized. All paperwork neat and tidy and no trash. All your computer files and folders should also be clean and easy to navigate using proper labeling techniques. As well, all equipment and cables should be neat and tidy. Treat your room like Diana Ross is coming over.

- Act like a pro and you will be treated like a pro. You run the session, you set the vibe and the tone. If you practice being organized, together, and cool, that comes across as what you are, and is how you are perceived and treated by others. You become what you practice.

Microphones

- What is a microphone? A microphone is a transducer that changes acoustic energy to electrical energy. Sound causes the diaphragm within the microphone to vibrate, creating a small voltage. Louder signals cause the microphone’s diaphragm to vibrate more, creating more voltage.

- The diaphragm is the internal membrane (or the ribbon—depending on the microphone) within the capsule that vibrates. Different microphones will display different frequency response charts. (See more later in this chapter.)

- A small diaphragm microphone will commonly, but not always, accentuate mid- to high frequencies. Due to the smaller mass of the smaller diaphragm, the low frequencies may not be as accurate as in a large diaphragm microphone.

- Large diaphragm microphones might offer the widest range of frequency response to capture warmth, as in low strings or vocals. These microphones tend to naturally recreate better low frequencies simply due to the mass of the diaphragm. Note that the larger the mass, the less accurate the transient response. These microphones may not accurately pick up higher frequencies from side angles, as the sound wave hits one side of the capsule before it reaches the other, causing cancellation.

- What is transient response? Transient response is the measurement of how accurate an electronic device translates its input signal.

- Do a listening test. When you understand the characteristics of each microphone, you are better equipped to choose the best microphone for each situation. A listening test will help train your ears to determine which microphone does what. Once trained, you use your ears and your experience to choose the best microphone.

- Set up the best few microphones available, perhaps four or five at a time, with the individual capsules adjacent to one another. Use no pads or roll-offs, and match the polar patterns. Set the faders so all the microphones have the same perceived volume. Have someone stand at an equal distance from all microphones and speak or sing. Switch one microphone on at a time and listen to which ones:

- Produce a nice crisp high end.

- Produce a warmer midrange.

- Retain warmth and smoothness no matter what frequencies are altered. Lower-quality microphones may start to sound brittle as you boost the higher frequencies.

- Have a thick bottom.

- Produce hums or buzzes. Microphones with inherent lower levels may be noisier simply because the level must be raised to match the rest of the microphones being tested. Older tube microphones can have this problem, but their great sound makes up for it.

- Change level uniformly as the person moves about the microphone. Some cardioid microphones are more omni-directional than others, and some may not be omni-directional at all frequencies.

- What is the proximity effect? The proximity effect is the increase in a microphone’s low frequency response when it’s placed very close to a sound source. Microphones with omni-directional patterns are not affected by the proximity effect.

- What is phantom power? Condenser microphone capsules are very high impedance, so they need an impedance converter circuit that requires power to operate. This power is called phantom power, and it comes from the mixer microphone input. Dynamic microphones have no active electronics, so phantom power is not needed.

- What is a pre-amplifier? Whether inside or outside the console, the microphone pre-amp raises the microphone signal level to a usable ‘line level.’

- What does frequency response mean? A device’s frequency response is its output level versus frequency. Different microphones will display different frequency response charts. All new microphones come with a response chart. Figure 3.4 shows a readout page that shows some microphones will have a smooth high end, while others may have an upper midrange bump. While these charts may not be readily available for you to refer to, simply listening to different microphones on a similar sound source will result in a general idea of how a microphones chart would look.

- What does transient response mean? Transients are the initial sudden peaks of a sound, and are very short in duration. Transient response is the measure of how quickly a device responds to these transients. A percussion instrument contains very high transients, as can vocal sibilance.

- Which microphone is best? The best microphone is the one that sounds best in a particular situation. Unless you are totally familiar with all the microphones at your disposal, the only way to tell is to set up all the available microphones and listen. With experience, you will learn the characteristics of each microphone, and choosing which ones are best for different situations will come naturally. Microphones are the tools of your trade; learn them.

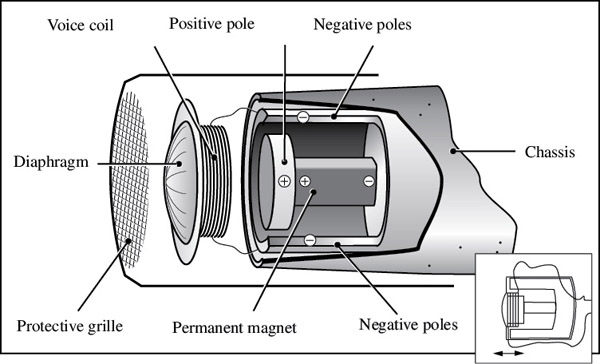

Dynamic Microphone

Dynamic moving coil microphones use a coil of wires attached to a diaphragm, which is suspended within a magnetic field (Figure 3.5). Acoustical vibrations cause the diaphragm and the coil to vibrate within this magnetic field, creating current that electrically represents the audio signal.

Dynamic microphones tend to be robust, and are commonly used for the close miking of louder instrument setups including guitar amplifiers, drums, and live vocals. Characteristics include a good transient response, a natural midrange peak (about 5 kHz), solid low-frequency response, and tight polar pattern to keep leakage at bay. Because of their rugged build, dynamic microphones are often used in live situations.

Condenser Microphone

Condenser microphones use two adjacent plates. One is stationary, while the other, a diaphragm, vibrates to incoming acoustic signal. These two plates are charged with a constant voltage—phantom power. As the distance between the diaphragm and the stationary plate varies with incoming vibrations, a varying electrical current is generated (Figure 3.6).

Condensers tend to be less robust than dynamics, usually a bit warmer and smoother, and they capture a wide frequency range. They might be used on instrument setups such as vocals, acoustic instruments, room ambiance and less powerful electric instruments. Because all condenser microphones have a pre-amp, their output voltage is much higher than a dynamic microphone.

- What are tube microphones? Standard condenser microphones use internal transistors to pre-amplify the very small electrical current produced by the charged diaphragm. Some condenser microphones use tubes, not transistors. These tube microphones have their own power supply that charges the tube and the diaphragm. Tube microphones are expensive and delicate, but create a super warm round sound.

Ribbon Microphone

Ribbon microphones use the same principle as dynamic microphones, only rather than a coil of wire, they use a ribbon of metal foil (Figure 3.7). This foil ribbon vibrates within a strong magnetic field, creating a small electric current. This field is strong. Not strong enough to pull your belt off, but maybe strong enough to erase a tape, if you are fortunate enough to be working with analog tape.

Ribbon microphones traditionally record wonderfully lush low end and sound great for male vocals or bass due to their natural internal compression. Be warned—these microphones are quite sensitive to air movement and tend not to be as robust as dynamic moving coil microphones; too much signal can stretch the ribbon. Additionally, ribbon microphones are known for having a solid Figure-8 pattern that tends to be smooth and accurate.

Due to the sensitive nature of the ribbon, confirm that the phantom power is switched off when using a ribbon microphone.

Additional Microphones

Additional microphone styles include:

- Boundary microphone. A boundary microphone uses a flat plate and adjacent microphone capsule placed, commonly taped to a wall, or the floor, or maybe under the lid of a grand piano to pick up direct and reflected sounds in phase.

- Lavalier microphone. Contact microphones, sometimes called lapel microphones or simply ‘lavs,’ are small and commonly used for unobtrusive recording, such as when clipped to a lapel in television interviews.

- Shotgun microphone. This ultra-directional microphone receives all the incoming sounds, but cancels out everything except for what is directly in front of the microphone. Shotguns are commonly used on film and location settings.

- • What are pads/roll-offs? A microphone pad is a circuit inserted at the microphone to lower the level reaching the console, such as −10 dB, −20 dB, even −30 dB. A roll-off is a low-end or high-end filter on the microphone used to eliminate the high or low frequencies that are not needed as an essential part of a sound. Use a low-end roll-off (HPF or high-pass filter) to minimize rumble on a vocal track, or a high-end roll-off (LPF or low-pass filter) to reduce sizzle from a high hat microphone without adding equalization.

Polar Patterns

Signal arrives to the microphone from 360°. A polar pattern is a graph of microphone sensitivity versus the angle of the incoming sound. Signals picked up in front of the microphone, or what the microphone is aimed at, are called on-axis. Signals arriving from the back and sides are referred to as off-axis. Off-axis signal sounds lower in level, duller and less present that the clear crisp on-axis sound.

Some microphones have only one pattern, others have switchable patterns, and even others have changeable capsules, each containing a different pad or polar pattern.

- What is a cardioid pattern? Cardioid patterns are so called because their pickup pattern is shaped not unlike a heart (Figure 3.8). Note that pickup on the front is best, and level decreases as sound arrives from the sides and back. High frequencies are the first to decrease as we approach the sides and back of the microphone. As frequencies lower, cardioid patterns become more omni-directional.

- What is an omni-directional pattern? Omni-directional patterns are so called because they pick up signal from all sides equally (Figure 3.9). This is not so great for live applications as it picks up bleed from the other instruments. As the frequencies rise, the omni pattern becomes more directional.

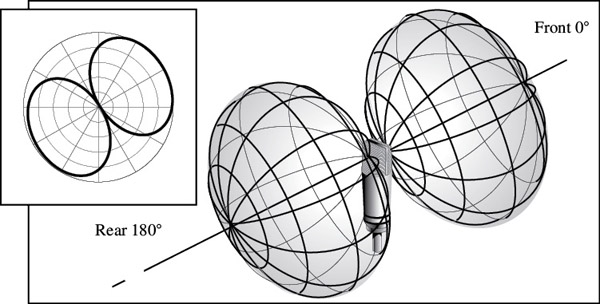

- What is a Figure-8 pattern? The Figure-8 (bi-directional or bi-polar) pattern is so called because it is shaped like an 8, picking up signal from both sides of the microphone while rejecting off-axis signals. In bi-polar patterns, one side of the pattern is internally set out-of-phase with the other (Figure 3.10).

- No more embarrassing leakage. Due to the way sound arrives at the capsule from all angles, the on-axis sound to be recorded is naturally mixed in with the off-axis debris. Proper microphone placement results in reducing off-axis leakage. Of course proper room design minimizes issues created with off-axis sounds, but these reflections still color the sound.

- Minimize leakage by using a Figure-8 polar pattern to cancel off-axis signal arriving from the side of the microphone. Note that any opposite reflection must be addressed as the polar pattern picks up sound on the opposite lobe of the microphone. Maybe aim the back of the microphone into a dead space.

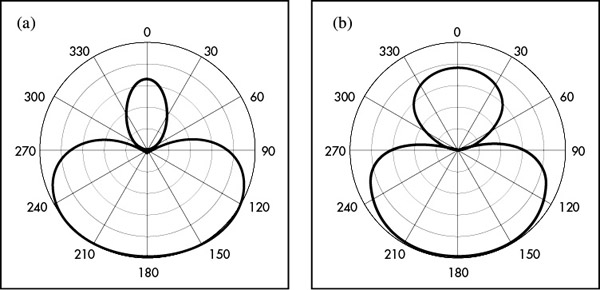

- Additional polar patterns. Additional, more directional patterns are variations on these main three patterns—the omni-directional, the cardioid, and the Figure-8. Figure 3.11 shows additional patterns including (a) super-cardioid and (b) hyper-cardioid patterns. These can be great for live applications as the rejection from sides and some of the back helps reduce feedback and other live sound issues.

Microphone Choice

- Match the microphone to the situation. Match the characteristics of the microphone with the characteristics of the instrument to complement its sound. If, for example, a microphone has a natural low-end boost, maybe use it on a small acoustic guitar that needs a low-end boost, rather than on a bass amplifier, which may have enough low frequencies. Questions to ask before choosing the microphones might include:

- Is a microphone even necessary? Some instruments have a direct output that can be used instead of a microphone. This means no leakage from other instruments. Sometimes, such as in a live situation, the best microphone choice is no microphone at all.

- How much air is being pushed? Does the situation call for a dynamic, a condenser, a ribbon, or another kind of microphone?

- What is the dynamic range of the musical instrument? A piano has a wide frequency range, a triangle doesn’t. Instruments with narrow frequency ranges may not need the best microphone in the house.

- Will an older tube microphone work better than a new one?

- Should a small or large diaphragm microphone be used? Different microphones naturally produce different responses—the ears are the final judges. Commonly, lower-frequency instruments benefit from large diaphragm microphones due to the larger diaphragm mass, which improves low-frequency response.

- How loud is the microphone? A microphone with a high output might not be the best choice for a really loud instrument, just like a low sensitivity microphone might not be the best choice for a low output instrument.

- Where is the best placement for optimum response? Does the situation call for direct signal, close miking, or not so close miking?

- What microphone polar patterns are available, and which is best for this situation? Don’t necessarily choose a cardioid pattern. Sometimes using an omni-directional microphone with properly placed absorption devices works well, as the omni pattern captures a more natural sound, and placement or aim is not as critical. Sometimes a Figure-8 is best to eliminate sounds arriving to the microphone from the side, or off-axis.

- How many microphones are needed? Will one be enough, or are two (or more) needed? Should stereo miking be used?

- Is a pad or roll-off necessary? After the levels have been lowered, is signal still too loud?

- Should I have the chicken or the fish for lunch?

- Try all the microphones available. Don’t forget about that one humble microphone that sits in the corner of your arsenal for years and never gets used. I wonder how a shotgun microphone aimed at a guitar amplifier would sound, or a boundary microphone taped to the floor under a guitar amplifier, or a lavalier clipped to the hole of an acoustic guitar?

Microphone Setup

- Treat microphones with the utmost care. Microphones are like children. Handle them with utmost care, never leave them on the floor, and they respond best when locked in a dark closet overnight.

- Bring the microphones into the studio and immediately set them on their proper stand. If you must set the microphone down, place it on a blanket or towel. Your microphones should be treated like gold to stay pristine. Take extra care with older tube microphones as they are expensive to fix and repair can take months.

- Check please. Double check, then triple check that the microphone is attached to the stand correctly, not touching any other stands or instruments, and is solidly in place.

- Mute the microphone before plugging in the cable. At this point of your setup, the proper cable should lie at the base of the microphone stand. Check with the control room that the channel is turned off. This avoids a great loud pop in the speakers and, even worse, through all the headphones.

- Switch off the phantom power. If the microphone has its own power supply, as many tube microphones do, turn off the phantom power at the console. As well, switch it off for dynamic and unbalanced microphones.

- Three-to-one rule. There is an old rule when placing two or more microphones on a single source. Place the second microphone at least three times the distance measured between the first microphone and its sound source. At this distance, the second microphone picks up enough of the room ambiance to minimize any phase interference between the two microphones. Figure 3.12 shows that microphone (a) is one foot from the acoustic guitar source, and that microphone (b) is beyond the three-foot perimeter.

- This rule can be broken when two microphones are placed so close together that they are in phase, such as two microphones taped together and aimed at a snare drum.

- As well as using the 3-to-1 rule on one instrument, the rule applies when you are placing microphones on two different instruments. The second microphone aimed at its own sound source should be at least three times the distance away from the first microphone and its sound source. This is a rule that sounds good on paper, but your situation will dictate.

- Port noise complaint. Blocking the ports of a microphone will change the polar pattern. Placing a microphone too close to the floor, wall, window, or any other reflective surface may cause unwanted reflections to bounce back into the microphone. Tighten the microphone’s polar pattern using damping, such as a carpet on the surface, to reduce these close reflections.

- Set up a talkback microphone. A talkback microphone is a microphone placed in the middle of the recording room so the players can communicate with the people in the control room. Set up an omni-directional patterned talkback microphone early in the setup, as proper communication between studio and control room shortens setup time.

- Install a reverse gate on the talkback microphone. This is what happens. The talkback microphone is turned up so the control room hears someone across the studio talking. When the band starts to play, usually loud, the room sound comes through the talkback microphone loud and clear.

- To avoid this, install a reverse gate. Technically, a reverse gate is a compressor whose response is absolute. When the threshold is met, it shuts off the room microphone. When the players play, the volume in the studio will cause the gate to react, in effect turning off the talkback microphone. When the music stops, the gate opens and activates the talkback microphone. This allows more freedom than always having to reach over and continually turn the talkback microphone on and off.

Close Miking

- Just as it sounds. Close miking means placing the microphone within inches of the source. Some advantages of close miking might include:

- A fuller tighter sound.

- Minimal leakage from other instruments.

- No unwanted ambiance on a track. If needed, ambiance can be added to a dry track, but once recorded, ambiance cannot be removed.

- Easier to return to the same sound if ambiance is different, such as when using a different studio.

- More separation when recording in stereo.

- Pull back. One of the reasons microphones are placed close to the source is to minimize leakage from other instruments from entering our microphone. However, this can compromise the warmth of the sound. A microphone placed too close to a source might compromise warmth. The hottest part of the match is not right at the head, it is farther away in the flame. The strongest part of a waterfall is not at the crest, but farther down, where it has had time to build power. If there are no other instruments in the vicinity, maybe pull the microphone back a bit to allow the sound to build.

- Get down on your knees and play. Every setup has a sweet spot, or the best place for the microphone for your situation. Find the sweet spot by listening. Get down on your knees and have the player play. Not loud, but loud enough for you to move your head around and hear. On an amplifier, ask the player to turn down and play while you find the best place for the microphone.

- Fine placement. You can really hear differences in the sound as you move the close microphone around in front of the source. As the microphone moves away from the source, slight changes in microphone placement aren’t as apparent. Turn the amplifier down while someone moves the microphone around in front of the amplifier while you listen in the control room. When you hear the right spot, ask the player to stop, indicating to the person moving the microphone around that he has found the perfect place, and to secure the microphone in that exact spot.

- Commonly a good placement for a close microphone on an amplifier is aimed a few inches away from where the outer cone meets the inner sphere of the speaker. This is a good starting point.

Distant Miking

- Go the distance. Distant miking means the microphone is placed a few feet or more from the source. Advantages of distant miking include:

- A more ambient sound with greater influence from the surrounding environment. Ambiance can help establish a sense of depth. Take note: ambiance microphones, also called room microphones, can reveal flaws in the room design. This means buildup of certain frequencies in certain areas within the room.

- Not in the way of players, as they need to be totally comfortable.

- A second distant microphone recorded on a separate track can aid in depth and placement within the stereo spectrum when mixing.

- Able to pick up a large group of musicians. (Have you ever tried to pick up a large group of musicians?) When distant miking a group of players, usually for classical music, the tonal balance captured can be better than recording with separate close microphones. The players can mix themselves better than the engineer.

- Less dynamics, often associated with, for example, vocals. With close miking, a compressor is almost a necessity, unless the singer is really good and knows how to control the dynamics of his voice. A foot or more distance between singer and microphone causes less change in level. The farther away the singer is from the microphone the more the surrounding environment gets recorded with the vocal. This is when studio design comes into factor.

- Learn from history. In the early days of recording, one microphone was strategically placed in the studio and moved around until all the instruments were heard properly, then naturally mixed correctly onto one track. They recorded everything onto this mono track, and the recordings were magnificent. The space between the source instruments and the microphone would create its own mix using natural compression, unifying the instruments into a mix that gels the sounds together naturally.

- Plus without the advent of overdubs, everyone was watching each other, sweating together, grooving to the same wave. A group of players playing a song as one cohesive unit will always sound better than each player overdubbing his part.

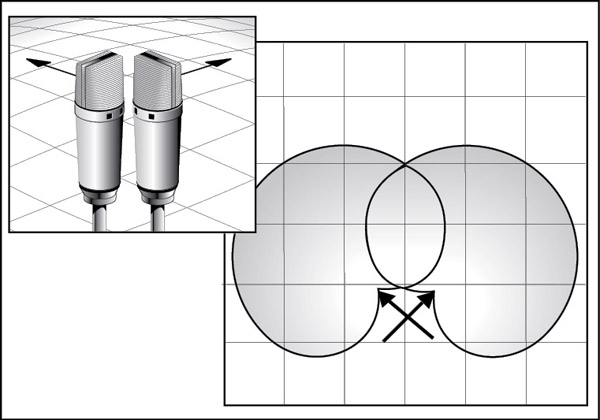

X/Y Stereo Miking

- X marks the spot. To produce a full stereo sound, place matching microphones (often microphones with concurrent serial numbers are very close in sound) in an ‘X’ position with their capsules close together (Figure 3.13). This setup essentially eliminates any phase problems between the two microphones. Use X/Y miking in restricted spaces where microphones need to be somewhat close together yet produce a good stereo image such as over a piano, or above a violin section.

- The angle of the microphones will determine the stereo spread. The wider the angle, the more stereo spread, until the angle gets too wide, creating a hole in the middle. The narrower the angle, the less of a hole, creating more of a mono signal.

- Set up the two microphones so both are at the same height, and have the same directional polar pattern with matching pads and roll-offs.

‘Spaced Pair’ Stereo Miking

- Get spaced. A standard spaced pair technique places the microphones far apart within the recording room. The darker areas on Figure 3.14 show the common pickup areas. Setups might include:

- (a) Quite a few yards apart. These room microphones pick up an ambient stereo room sound.

- (b) Two feet to three feet apart. The wider the spacing, the wider the stereo spread. This setup gives a good stereo image without too much ambiance.

- (c) Parallel, in front of an instrument. Both microphones aimed toward the source gives a wide stereo image. For an even wider image, place a baffle between the microphones.

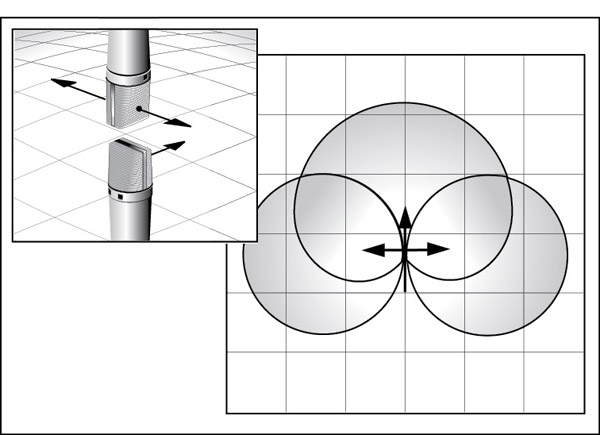

M/S Stereo Miking

- We both have mono. M/S stands for either middle/side, or mono/stereo. This method ‘sums and differences’ the polar patterns of two microphones.

- Use M/S when you need to decide later how wide the stereo image should be (Figure 3.15). To monitor and control the depth of the stereo image, three channels are needed on the console. These channels are mixed to two tracks.

- (1) Set up two microphones, one with a cardioid pattern ‘M,’ the other with a Figure-8 pattern ‘S.’

- (2) Aim the M microphone toward the source. Position the S microphone on the same plane, but at a 90° angle.

- (3) Route the M microphone to record on track one, and route the S microphone to record on track two. The M microphone returns from the multitrack recorder into channel one, and the S microphone returns into channel two.

- (4) Route the S signal out of channel two into channel three so it returns on both two and three. Switch channel three out of phase.

- (5) Pan channel one to the center, then pan two and three hard L/R.

- (6) Raise channel one to set the appropriate mono level, then raise channels two and three to control the stereo width.

- Note that while collapsing your two XY stereo channels to mono can result in some phase cancellation, MS folds into a perfectly clean direct mono sound.

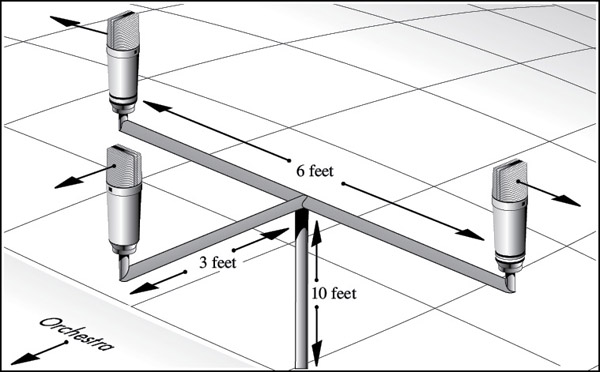

Decca Tree Stereo Miking

- Decca records. The Decca tree setup, used for larger situations, uses a three-microphone array (Figure 3.16). All three are set in an omni-directional pattern, then placed left, center, and right a few feet behind and about ten feet above the conductor. Decca tree recording is becoming more popular in L-C-R (left, center, right) stereo, and 5.1 surround DVD recordings.

- Decca tree stereo miking records not only on the left/right location of instruments but the fore and background location, crucial for orchestral sessions where depth and dimension would be lost with close miking.

Ground

- Ground hum. Ground loop and the resulting hum occur when electrical equipment is grounded to more than one location, creating multiple paths. As well, hum can originate from fluorescent lights, video monitors, dimmer switches, refrigerators, and more.

- Eliminate the hum. If your audio equipment setup is humming:

- Use a dedicated AC power circuit for the studio. Some studios have outlets strictly for audio equipment, often indicated by orange wall outlets. Sometimes all the audio equipment is plugged into a large 12-outlet box, with everything on the same circuit. The outlets in the rest of the studio would be on a separate circuit, and used for the coffee machine, the video games, and the vibrating bed.

- Don’t plug a power strip into another power strip.

- Eliminate all fluorescent lights in the vicinity.

- Don’t use a ground lifter—a converter that changes a three-prong plug to a two-prong plug. This can be dangerous. The third pin is there to keep you safe. Most equipment today is fitted with three-prong outlets, the third being a chassis ground just to avoid any bothersome recording engineer electrocution issues.

- Use a transformer, or hum remover, made specifically to eliminate hum by removing any common ground between devices.

- Use the highest quality, shortest cables.

- Rearrange the way the outboard equipment is stacked. A transformer in one unit may cause hum in an adjacent unit.

- Use a filter. Although not recommended, a 60 Hz hum can be removed using a filter set at 60 Hz and 120 Hz. But this pulls that frequency on any musical content and can affect harmonics.

- Switch the direct box ground. Some direct boxes have a ground switch that disconnects the input cable shield from the output cable shield, eliminating ground loops and the resulting hum.

- When the hum is from a guitar amplifier, plug the amplifier into a different wall outlet on a different circuit.

- Have the player rotate. Single-coil pickups in guitars are notorious for humming when the player is aimed in a certain direction. The hum disappears when he points in another direction. When you find the quietest angle for the player to stand, run a section of sticky tape across the floor so the player knows just what the angle should be.

- If you still can’t find the hum, use the process of elimination: shut everything off, and start at the beginning turning everything on again. When the hum starts, that’s the culprit.

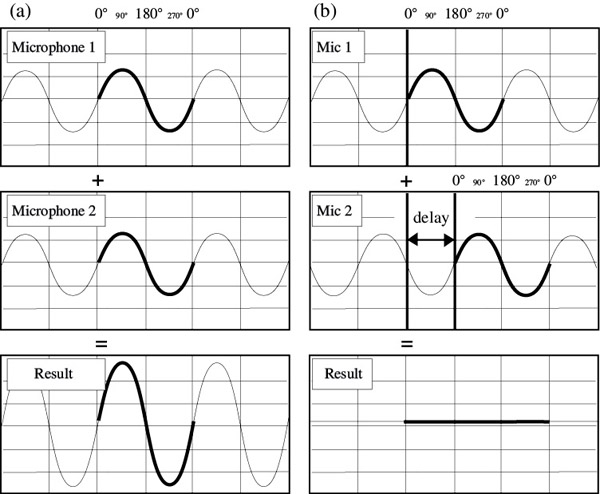

Phase

- Phase issues. When identical signals combine, such as when two microphones are bussed to one track, phase shift can be introduced when one of the signals is delayed. This shift or delay is measured in degrees. Figure 3.17 (a) shows that when similar sine waves combine with no delays, the signal doubles. Figure 3.17 (b) shows that when one signal is delayed exactly half the length of the sound wave, its polarity is 180° out-of-phase with the other signal. When combined, these signals will cancel each other out. Note that phase or phase shift involves delay. Polarity does not. Polarity refers to the + or − direction of an electrical signal.

- What is a phase meter? The readout pattern on the phase meter screen displays a L versus R output that corresponds with the tracks you are monitoring.

- Check for polarity. Somewhere along the line between microphone and monitor, the polarity may be reversed. Perhaps it’s a miswired connector or input jack, maybe even a wrong button pressed. To check for polarity:

- (1) Place matching microphones right next to each other, with the capsules as close as possible, both aimed toward a source.

- (2) Have someone stand a few feet away and speak.

- (3) Solo the two channels, and listen in mono.

- (4) Press the phase button (sometimes mislabeled as polarity) on one of the microphone channels. If the signal cancels, the microphones have the same polarity. If the signal cancels when no buttons are pressed, the two microphones are wired in opposite polarity (the wiring to pins 2 and 3 are reversed in one microphone’s XLR connector).

- Phase—the facts. Every foot that you move a microphone away from the source results in about a one-millisecond delay. If a second microphone is placed incorrectly, the signal reaches it at a different time in the cycle.

- At specific distances, certain frequencies will be out-of-phase, resulting in a thin, incomplete sound. This phenomenon occurs when recording any sound with two inputs, such as when combining a direct box and a distant microphone.

- What does out of phase sound like? Phase issues occur between at least two inputs from a common source, such as between top and bottom snare microphones, kick and snare, microphones inside and outside the kick drum, overheads and tom-tom microphones, and all combinations.

- Phase can be checked by listening to the whole kit in mono, or listening to various combinations of microphones on the drums. Traditionally, a phase meter sits near the recording engineer, showing a readout of the phase on any give track or combination of tracks.

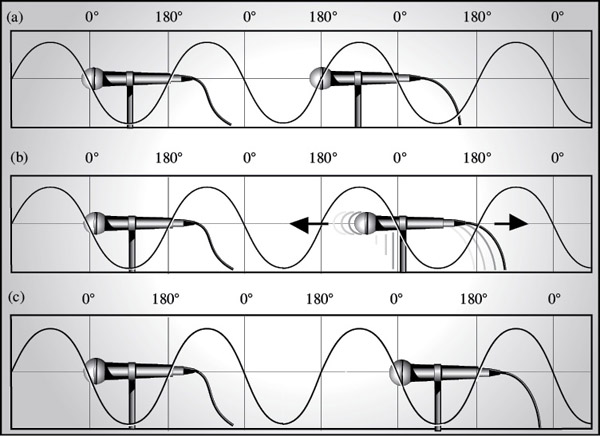

- Figure 3.18 (a) shows two microphones placed as the session dictates. Solo the two channels, match the levels, and listen in mono. At the console, temporarily switch the polarity on the channel with the farthest microphone from the sound source. With the phase button pressed, you should lose lots of low end because of signal cancellations.

- Can you fix the phase issues using a switch at the console? During basics, yes you can, by using the phase button to pinpoint an issue at the source, then fix the issue before recording. Go out into the room and physically move the microphone a bit, then go back into the control room and start the listening process over. Soon everything should be well in phase.

- Move the microphone and stand. To check for phase issues between two microphones near and far on an amplifier, switch the phase button on the input channel with the farthest microphone in the setup. Have the player play, preferably a single note, while an assistant moves the distant microphone, Figure 3.18 (b), stand and all, forward and back again. When the combined sound source almost disappears, the two signals are out-of-phase, canceling each other.

- Place the distant microphone in that spot. Switch the phase button on the console back again. Figure 3.18 (c) shows the farthest microphone is back in phase with the close microphone.

- Which way to the bar? When you think you are in phase, record a few bars of music, then go to the edit window, zoom in on the tracks and see if the waveforms line up. Slightly move one of the microphones and record another few bars until the phase is perfect.