Chapter 7

Encapsulation

Perhaps the most important criteria to be used in decomposing modules is to identify secrets that modules should hide from the rest of the system [Parnas]. Data structures are the most common secrets, and I can hide data structures by encapsulating them with Encapsulate Record (162) and Encapsulate Collection (170). Even primitive data values can be encapsulated with Replace Primitive with Object (174)—the magnitude of second-order benefits from doing this often surprises people. Temporary variables often get in the way of refactoring—I have to ensure they are calculated in the right order and their values are available to other parts of the code that need them. Using Replace Temp with Query (178) is a great help here, particularly when splitting up an overly long function.

Classes were designed for information hiding. In the previous chapter, I described a way to form them with Combine Functions into Class (144). The common extract/inline operations also apply to classes with Extract Class (182) and Inline Class (186).

As well as hiding the internals of classes, it’s often useful to hide connections between classes, which I can do with Hide Delegate (189). But too much hiding leads to bloated interfaces, so I also need its reverse: Remove Middle Man (192).

Classes and modules are the largest forms of encapsulation, but functions also encapsulate their implementation. Sometimes, I may need to make a wholesale change to an algorithm, which I can do by wrapping it in a function with Extract Function (106) and applying Substitute Algorithm (195).

Encapsulate Record

formerly: Replace Record with Data Class

Motivation

This is why I often favor objects over records for mutable data. With objects, I can hide what is stored and provide methods for all three values. The user of the object doesn’t need to know or care which is stored and which is calculated. This encapsulation also helps with renaming: I can rename the field while providing methods for both the new and the old names, gradually updating callers until they are all done.

I just said I favor objects for mutable data. If I have an immutable value, I can just have all three values in my record, using an enrichment step if necessary. Similarly, it’s easy to copy the field when renaming.

I can have two kinds of record structures: those where I declare the legal field names and those that allow me to use whatever I like. The latter are often implemented through a library class called something like hash, map, hashmap, dictionary, or associative array. Many languages provide convenient syntax for creating hashmaps, which makes them useful in many programming situations. The downside of using them is they are aren’t explicit about their fields. The only way I can tell if they use start/end or start/length is by looking at where they are created and used. This isn’t a problem if they are only used in a small section of a program, but the wider their scope of usage, the greater problem I get from their implicit structure. I could refactor such implicit records into explicit ones—but if I need to do that, I’d rather make them classes instead.

It’s common to pass nested structures of lists and hashmaps which are often serialized into formats like JSON or XML. Such structures can be encapsulated too, which helps if their formats change later on or if I’m concerned about updates to the data that are hard to keep track of.

Mechanics

Use Encapsulate Variable (132) on the variable holding the record.

Give the functions that encapsulate the record names that are easily searchable.

Replace the content of the variable with a simple class that wraps the record. Define an accessor inside this class that returns the raw record. Modify the functions that encapsulate the variable to use this accessor.

Test.

Provide new functions that return the object rather than the raw record.

For each user of the record, replace its use of a function that returns the record with a function that returns the object. Use an accessor on the object to get at the field data, creating that accessor if needed. Test after each change.

If it’s a complex record, such as one with a nested structure, focus on clients that update the data first. Consider returning a copy or read-only proxy of the data for clients that only read the data.

Remove the class’s raw data accessor and the easily searchable functions that returned the raw record.

Test.

If the fields of the record are themselves structures, consider using Encapsulate Record and Encapsulate Collection (170) recursively.

Example

I’ll start with a constant that is widely used across a program.

const organization = {name: "Acme Gooseberries", country: "GB"};

This is a JavaScript object which is being used as a record structure by various parts of the program, with accesses like this:

result += `<h1>${organization.name}</h1>`;

and

organization.name = newName;

The first step is a simple Encapsulate Variable (132).

function getRawDataOfOrganization() {return organization;}

example reader…

result += `<h1>${getRawDataOfOrganization().name}</h1>`;

example writer…

getRawDataOfOrganization().name = newName;

It’s not quite a standard Encapsulate Variable (132), since I gave the getter a name deliberately chosen to be both ugly and easy to search for. This is because I intend its life to be short.

Encapsulating a record means going deeper than just the variable itself; I want to control how it’s manipulated. I can do this by replacing the record with a class.

class Organization…

class Organization { constructor(data) { this._data = data; } }

top level

const organization = new Organization({name: "Acme Gooseberries", country: "GB"}); function getRawDataOfOrganization() {return organization._data;} function getOrganization() {return organization;}

Now that I have an object in place, I start looking at the users of the record. Any one that updates the record gets replaced with a setter.

class Organization…

set name(aString) {this._data.name = aString;}

client…

getOrganization().name = newName;

Similarly, I replace any readers with the appropriate getter.

class Organization…

get name() {return this._data.name;}

client…

result += `<h1>${getOrganization().name}</h1>`;

After I’ve done that, I can follow through on my threat to give the ugly sounding function a short life.

function getRawDataOfOrganization() {return organization._data;}

function getOrganization() {return organization;}

I’d also be inclined to fold the _data field directly into the object.

class Organization {

constructor(data) {

this._name = data.name;

this._country = data.country;

}

get name() {return this._name;}

set name(aString) {this._name = aString;}

get country() {return this._country;}

set country(aCountryCode) {this._country = aCountryCode;}

}

This has the advantage of breaking the link to the input data record. This might be useful if a reference to it runs around, which would break encapsulation. Should I not fold the data into individual fields, I would be wise to copy _data when I assign it.

Example: Encapsulating a Nested Record

The above example looks at a shallow record, but what do I do with data that is deeply nested, e.g., coming from a JSON document? The core refactoring steps still apply, and I have to be equally careful with updates, but I do get some options around reads.

As an example, here is some slightly more nested data: a collection of customers, kept in a hashmap indexed by their customer ID.

"1920": {

name: "martin",

id: "1920",

usages: {

"2016": {

"1": 50,

"2": 55,

// remaining months of the year

},

"2015": {

"1": 70,

"2": 63,

// remaining months of the year

}

}

},

"38673": {

name: "neal",

id: "38673",

// more customers in a similar form

With more nested data, reads and writes can be digging into the data structure.

sample update…

customerData[customerID].usages[year][month] = amount;

sample read…

function compareUsage (customerID, laterYear, month) {

const later = customerData[customerID].usages[laterYear][month];

const earlier = customerData[customerID].usages[laterYear - 1][month];

return {laterAmount: later, change: later - earlier};

}

To encapsulate this data, I also start with Encapsulate Variable (132).

function getRawDataOfCustomers() {return customerData;} function setRawDataOfCustomers(arg) {customerData = arg;}

sample update…

getRawDataOfCustomers()[customerID].usages[year][month] = amount;

sample read…

function compareUsage (customerID, laterYear, month) {

const later = getRawDataOfCustomers()[customerID].usages[laterYear][month];

const earlier = getRawDataOfCustomers()[customerID].usages[laterYear - 1][month];

return {laterAmount: later, change: later - earlier};

}

I then make a class for the overall data structure.

class CustomerData { constructor(data) { this._data = data; } }

top level…

function getCustomerData() {return customerData;} function getRawDataOfCustomers() {return customerData._data;} function setRawDataOfCustomers(arg) {customerData = new CustomerData(arg);}

The most important area to deal with is the updates. So, while I look at all the callers of getRawDataOfCustomers, I’m focused on those where the data is changed. To remind you, here’s the update again:

sample update…

getRawDataOfCustomers()[customerID].usages[year][month] = amount;

The general mechanics now say to return the full customer and use an accessor, creating one if needed. I don’t have a setter on the customer for this update, and this one digs into the structure. So, to make one, I begin by using Extract Function (106) on the code that digs into the data structure.

sample update…

setUsage(customerID, year, month, amount);

top level…

function setUsage(customerID, year, month, amount) {

getRawDataOfCustomers()[customerID].usages[year][month] = amount;

}

I then use Move Function (198) to move it into the new customer data class.

sample update…

getCustomerData().setUsage(customerID, year, month, amount);

class CustomerData…

setUsage(customerID, year, month, amount) {

this._data[customerID].usages[year][month] = amount;

}

When working with a big data structure, I like to concentrate on the updates. Getting them visible and gathered in a single place is the most important part of the encapsulation.

At some point, I will think I’ve got them all—but how can I be sure? There’s a couple of ways to check. One is to modify getRawDataOfCustomers to return a deep copy of the data; if my test coverage is good, one of the tests should break if I missed a modification.

top level…

function getCustomerData() {return customerData;}

function getRawDataOfCustomers() {return customerData.rawData;}

function setRawDataOfCustomers(arg) {customerData = new CustomerData(arg);}

class CustomerData…

get rawData() { return _.cloneDeep(this._data); }

I’m using the lodash library to make a deep copy.

Another approach is to return a read-only proxy for the data structure. Such a proxy could raise an exception if the client code tries to modify the underlying object. Some languages make this easy, but it’s a pain in JavaScript, so I’ll leave it as an exercise for the reader. I could also take a copy and recursively freeze it to detect any modifications.

Dealing with the updates is valuable, but what about the readers? Here there are a few options.

The first option is to do the same thing as I did for the setters. Extract all the reads into their own functions and move them into the customer data class.

class CustomerData…

usage(customerID, year, month) { return this._data[customerID].usages[year][month]; }

top level…

function compareUsage (customerID, laterYear, month) {

const later = getCustomerData().usage(customerID, laterYear, month);

const earlier = getCustomerData().usage(customerID, laterYear - 1, month);

return {laterAmount: later, change: later - earlier};

}

The great thing about this approach is that it gives customerData an explicit API that captures all the uses made of it. I can look at the class and see all their uses of the data. But this can be a lot of code for lots of special cases. Modern languages provide good affordances for digging into a list-and-hash [mf-lh] data structure, so it’s useful to give clients just such a data structure to work with.

If the client wants a data structure, I can just hand out the actual data. But the problem with this is that there’s no way to prevent clients from modifying the data directly, which breaks the whole point of encapsulating all the updates inside functions. Consequently, the simplest thing to do is to provide a copy of the underlying data, using the rawData method I wrote earlier.

class CustomerData…

get rawData() { return _.cloneDeep(this._data); }

top level…

function compareUsage (customerID, laterYear, month) {

const later = getCustomerData().rawData[customerID].usages[laterYear][month];

const earlier = getCustomerData().rawData[customerID].usages[laterYear - 1][month];

return {laterAmount: later, change: later - earlier};

}

But although it’s simple, there are downsides. The most obvious problem is the cost of copying a large data structure, which may turn out to be a performance problem. As with anything like this, however, the performance cost might be acceptable—I would want to measure its impact before I start to worry about it. There may also be confusion if clients expect modifying the copied data to modify the original. In those cases, a read-only proxy or freezing the copied data might provide a helpful error should they do this.

Another option is more work, but offers the most control: Apply Encapsulate Record recursively. With this, I turn the customer record into its own class, apply Encapsulate Collection (170) to the usages, and create a usage class. I can then enforce control of updates by using accessors, perhaps applying Change Reference to Value (252) on the usage objects. But this can be a lot of effort for a large data structure—and not really needed if I don’t access that much of the data structure. Sometimes, a judicious mix of getters and new classes may work, using a getter to dig deep into the structure but returning an object that wraps the structure rather than the unencapsulated data. I wrote about this kind of thing in an article “Refactoring Code to Load a Document” [mf-ref-doc].

Encapsulate Collection

Motivation

I like encapsulating any mutable data in my programs. This makes it easier to see when and how data structures are modified, which then makes it easier to change those data structures when I need to. Encapsulation is often encouraged, particularly by object-oriented developers, but a common mistake occurs when working with collections. Access to a collection variable may be encapsulated, but if the getter returns the collection itself, then that collection’s membership can be altered without the enclosing class being able to intervene.

To avoid this, I provide collection modifier methods—usually add and remove—on the class itself. This way, changes to the collection go through the owning class, giving me the opportunity to modify such changes as the program evolves.

Iff the team has the habit to not to modify collections outside the original module, just providing these methods may be enough. However, it’s usually unwise to rely on such habits; a mistake here can lead to bugs that are difficult to track down later. A better approach is to ensure that the getter for the collection does not return the raw collection, so that clients cannot accidentally change it.

One way to prevent modification of the underlying collection is by never returning a collection value. In this approach, any use of a collection field is done with specific methods on the owning class, replacing aCustomer.orders.size with aCustomer.numberOfOrders. I don’t agree with this approach. Modern languages have rich collection classes with standardized interfaces, which can be combined in useful ways such as Collection Pipelines [mf-cp]. Putting in special methods to handle this kind of functionality adds a lot of extra code and cripples the easy composability of collection operations.

Another way is to allow some form of read-only access to a collection. Java, for example, makes it easy to return a read-only proxy to the collection. Such a proxy forwards all reads to the underlying collection, but blocks all writes—in Java’s case, throwing an exception. A similar route is used by libraries that base their collection composition on some kind of iterator or enumerable object—providing that iterator cannot modify the underlying collection.

Probably the most common approach is to provide a getting method for the collection, but make it return a copy of the underlying collection. That way, any modifications to the copy don’t affect the encapsulated collection. This might cause some confusion if programmers expect the returned collection to modify the source field—but in many code bases, programmers are used to collection getters providing copies. If the collection is huge, this may be a performance issue—but most lists aren’t all that big, so the general rules for performance should apply (Refactoring and Performance (64)).

Another difference between using a proxy and a copy is that a modification of the source data will be visible in the proxy but not in a copy. This isn’t an issue most of the time, because lists accessed in this way are usually only held for a short time.

What’s important here is consistency within a code base. Use only one mechanism so everyone can get used to how it behaves and expect it when calling any collection accessor function.

Mechanics

Apply Encapsulate Variable (132) if the reference to the collection isn’t already encapsulated.

Add functions to add and remove elements from the collection.

If there is a setter for the collection, use Remove Setting Method (331) if possible. If not, make it take a copy of the provided collection.

Run static checks.

Find all references to the collection. If anyone calls modifiers on the collection, change them to use the new add/remove functions. Test after each change.

Modify the getter for the collection to return a protected view on it, using a read-only proxy or a copy.

Test.

Example

I start with a person class that has a field for a list of courses.

class Person…

constructor (name) {

this._name = name;

this._courses = [];

}

get name() {return this._name;}

get courses() {return this._courses;}

set courses(aList) {this._courses = aList;}

class Course…

constructor(name, isAdvanced) {

this._name = name;

this._isAdvanced = isAdvanced;

}

get name() {return this._name;}

get isAdvanced() {return this._isAdvanced;}

Clients use the course collection to gather information on courses.

numAdvancedCourses = aPerson.courses .filter(c => c.isAdvanced) .length ;

A naive developer would say this class has proper data encapsulation: After all, each field is protected by accessor methods. But I would argue that the list of courses isn’t properly encapsulated. Certainly, anyone updating the courses as a single value has proper control through the setter:

client code…

const basicCourseNames = readBasicCourseNames(filename); aPerson.courses = basicCourseNames.map(name => new Course(name, false));

But clients might find it easier to update the course list directly.

client code…

for(const name of readBasicCourseNames(filename)) {

aPerson.courses.push(new Course(name, false));

}

This violates encapsulating because the person class has no ability to take control when the list is updated in this way. While the reference to the field is encapsulated, the content of the field is not.

I’ll begin creating proper encapsulation by adding methods to the person class that allow a client to add and remove individual courses.

class Person…

addCourse(aCourse) { this._courses.push(aCourse); } removeCourse(aCourse, fnIfAbsent = () => {throw new RangeError();}) { const index = this._courses.indexOf(aCourse); if (index === -1) fnIfAbsent(); else this._courses.splice(index, 1); }

With a removal, I have to decide what to do if a client asks to remove an element that isn’t in the collection. I can either shrug, or raise an error. With this code, I default to raising an error, but give the callers an opportunity to do something else if they wish.

I then change any code that calls modifiers directly on the collection to use new methods.

client code…

for(const name of readBasicCourseNames(filename)) {

aPerson.addCourse(new Course(name, false));

}

With individual add and remove methods, there is usually no need for setCourses, in which case I’ll use Remove Setting Method (331) on it. Should the API need a setting method for some reason, I ensure it puts a copy of the collection in the field.

class Person…

set courses(aList) {this._courses = aList.slice();}

All this enables the clients to use the right kind of modifier methods, but I prefer to ensure nobody modifies the list without using them. I can do this by providing a copy.

class Person…

get courses() {return this._courses.slice();}

In general, I find it wise to be moderately paranoid about collections and I’d rather copy them unnecessarily than debug errors due to unexpected modifications. Modifications aren’t always obvious; for example, sorting an array in JavaScript modifies the original, while many languages default to making a copy for an operation that changes a collection. Any class that’s responsible for managing a collection should always give out copies—but I also get into the habit of making a copy if I do something that’s liable to change a collection.

Replace Primitive with Object

formerly: Replace Data Value with Object

formerly: Replace Type Code with Class

Motivation

Often, in early stages of development you make decisions about representing simple facts as simple data items, such as numbers or strings. As development proceeds, those simple items aren’t so simple anymore. A telephone number may be represented as a string for a while, but later it will need special behavior for formatting, extracting the area code, and the like. This kind of logic can quickly end up being duplicated around the code base, increasing the effort whenever it needs to be used.

As soon as I realize I want to do something other than simple printing, I like to create a new class for that bit of data. At first, such a class does little more than wrap the primitive—but once I have that class, I have a place to put behavior specific to its needs. These little values start very humble, but once nurtured they can grow into useful tools. They may not look like much, but I find their effects on a code base can be surprisingly large. Indeed many experienced developers consider this to be one of the most valuable refactorings in the toolkit—even though it often seems counterintuitive to a new programmer.

Mechanics

Apply Encapsulate Variable (132) if it isn’t already.

Create a simple value class for the data value. It should take the existing value in its constructor and provide a getter for that value.

Run static checks.

Change the setter to create a new instance of the value class and store that in the field, changing the type of the field if present.

Change the getter to return the result of invoking the getter of the new class.

Test.

Consider using Rename Function (124) on the original accessors to better reflect what they do.

Consider clarifying the role of the new object as a value or reference object by applying Change Reference to Value (252) or Change Value to Reference (256).

Example

I begin with a simple order class that reads its data from a simple record structure. One of its properties is a priority, which it reads as a simple string.

class Order…

constructor(data) {

this.priority = data.priority;

// more initialization

Some client codes uses it like this:

client…

highPriorityCount = orders.filter(o => "high" === o.priority

|| "rush" === o.priority)

.length;

Whenever I’m fiddling with a data value, the first thing I do is use Encapsulate Variable (132) on it.

class Order…

get priority() {return this._priority;} set priority(aString) {this._priority = aString;}

The constructor line that initializes the priority will now use the setter I define here.

This self-encapsulates the field so I can preserve its current use while I manipulate the data itself.

I create a simple value class for the priority. It has a constructor for the value and a conversion function to return a string.

class Priority {

constructor(value) {this._value = value;}

toString() {return this._value;}

}

I prefer using a conversion function (toString) rather than a getter (value) here. For clients of the class, asking for the string representation should feel more like a conversion than getting a property.

I then modify the accessors to use this new class.

class Order…

get priority() {return this._priority.toString();}

set priority(aString) {this._priority = new Priority(aString);}

Now that I have a priority class, I find the current getter on the order to be misleading. It doesn’t return the priority—but a string that describes the priority. My immediate move is to use Rename Function (124).

class Order…

get priorityString() {return this._priority.toString();}

set priority(aString) {this._priority = new Priority(aString);}

client…

highPriorityCount = orders.filter(o => "high" === o.priorityString || "rush" === o.priorityString) .length;

In this case, I’m happy to retain the name of the setter. The name of the argument communicates what it expects.

Now I’m done with the formal refactoring. But as I look at who uses the priority, I consider whether they should use the priority class themselves. As a result, I provide a getter on order that provides the new priority object directly.

class Order…

get priority() {return this._priority;}

get priorityString() {return this._priority.toString();}

set priority(aString) {this._priority = new Priority(aString);}

client…

highPriorityCount = orders.filter(o => "high" === o.priority.toString()

|| "rush" === o.priority.toString())

.length;

As the priority class becomes useful elsewhere, I would allow clients of the order to use the setter with a priority instance, which I do by adjusting the priority constructor.

class Priority…

constructor(value) {

if (value instanceof Priority) return value;

this._value = value;

}

The point of all this is that now, my new priority class can be useful as a place for new behavior—either new to the code or moved from elsewhere. Here’s some simple code to add validation of priority values and comparison logic:

class Priority…

constructor(value) {

if (value instanceof Priority) return value;

if (Priority.legalValues().includes(value))

this._value = value;

else

throw new Error(`<${value}> is invalid for Priority`);

}

toString() {return this._value;}

get _index() {return Priority.legalValues().findIndex(s => s === this._value);}

static legalValues() {return ['low', 'normal', 'high', 'rush'];}

equals(other) {return this._index === other._index;}

higherThan(other) {return this._index > other._index;}

lowerThan(other) {return this._index < other._index;}

As I do this, I decide that a priority should be a value object, so I provide an equals method and ensure that it is immutable.

Now I’ve added that behavior, I can make the client code more meaningful:

client…

highPriorityCount = orders.filter(o => o.priority.higherThan(new Priority("normal")))

.length;

Replace Temp with Query

Motivation

One use of temporary variables is to capture the value of some code in order to refer to it later in a function. Using a temp allows me to refer to the value while explaining its meaning and avoiding repeating the code that calculates it. But while using a variable is handy, it can often be worthwhile to go a step further and use a function instead.

If I’m working on breaking up a large function, turning variables into their own functions makes it easier to extract parts of the function, since I no longer need to pass in variables into the extracted functions. Putting this logic into functions often also sets up a stronger boundary between the extracted logic and the original function, which helps me spot and avoid awkward dependencies and side effects.

Using functions instead of variables also allows me to avoid duplicating the calculation logic in similar functions. Whenever I see variables calculated in the same way in different places, I look to turn them into a single function.

This refactoring works best if I’m inside a class, since the class provides a shared context for the methods I’m extracting. Outside of a class, I’m liable to have too many parameters in a top-level function which negates much of the benefit of using a function. Nested functions can avoid this, but they limit my ability to share the logic between related functions.

Only some temporary variables are suitable for Replace Temp with Query. The variable needs to be calculated once and then only be read afterwards. In the simplest case, this means the variable is assigned to once, but it’s also possible to have several assignments in a more complicated lump of code—all of which has to be extracted into the query. Furthermore, the logic used to calculate the variable must yield the same result when the variable is used later—which rules out variables used as snapshots with names like oldAddress.

Mechanics

Check that the variable is determined entirely before it’s used, and the code that calculates it does not yield a different value whenever it is used.

If the variable isn’t read-only, and can be made read-only, do so.

Test.

Extract the assignment of the variable into a function.

If the variable and the function cannot share a name, use a temporary name for the function.

Ensure the extracted function is free of side effects. If not, use Separate Query from Modifier (306).

Test.

Use Inline Variable (123) to remove the temp.

Example

Here is a simple class:

class Order…

constructor(quantity, item) {

this._quantity = quantity;

this._item = item;

}

get price() {

var basePrice = this._quantity * this._item.price;

var discountFactor = 0.98;

if (basePrice > 1000) discountFactor -= 0.03;

return basePrice * discountFactor;

}

}

I want to replace the temps basePrice and discountFactor with methods.

Starting with basePrice, I make it const and run tests. This is a good way of checking that I haven’t missed a reassignment—unlikely in such a short function but common when I’m dealing with something larger.

class Order…

constructor(quantity, item) {

this._quantity = quantity;

this._item = item;

}

get price() {

const basePrice = this._quantity * this._item.price;

var discountFactor = 0.98;

if (basePrice > 1000) discountFactor -= 0.03;

return basePrice * discountFactor;

}

}

I then extract the right-hand side of the assignment to a getting method.

class Order…

get price() {

const basePrice = this.basePrice;

var discountFactor = 0.98;

if (basePrice > 1000) discountFactor -= 0.03;

return basePrice * discountFactor;

}

get basePrice() {

return this._quantity * this._item.price;

}

I test, and apply Inline Variable (123).

class Order…

get price() {

const basePrice = this.basePrice;

var discountFactor = 0.98;

if (this.basePrice > 1000) discountFactor -= 0.03;

return this.basePrice * discountFactor;

}

I then repeat the steps with discountFactor, first using Extract Function (106).

class Order…

get price() {

const discountFactor = this.discountFactor;

return this.basePrice * discountFactor;

}

get discountFactor() {

var discountFactor = 0.98;

if (this.basePrice > 1000) discountFactor -= 0.03;

return discountFactor;

}

In this case I need my extracted function to contain both assignments to discountFactor. I can also set the original variable to be const.

Then, I inline:

get price() {

return this.basePrice * this.discountFactor;

}

Extract Class

inverse of: Inline Class (186)

Motivation

You’ve probably read guidelines that a class should be a crisp abstraction, only handle a few clear responsibilities, and so on. In practice, classes grow. You add some operations here, a bit of data there. You add a responsibility to a class feeling that it’s not worth a separate class—but as that responsibility grows and breeds, the class becomes too complicated. Soon, your class is as crisp as a microwaved duck.

Imagine a class with many methods and quite a lot of data. A class that is too big to understand easily. You need to consider where it can be split—and split it. A good sign is when a subset of the data and a subset of the methods seem to go together. Other good signs are subsets of data that usually change together or are particularly dependent on each other. A useful test is to ask yourself what would happen if you remove a piece of data or a method. What other fields and methods would become nonsense?

One sign that often crops up later in development is the way the class is sub-typed. You may find that subtyping affects only a few features or that some features need to be subtyped one way and other features a different way.

Mechanics

Decide how to split the responsibilities of the class.

Create a new child class to express the split-off responsibilities.

If the responsibilities of the original parent class no longer match its name, rename the parent.

Create an instance of the child class when constructing the parent and add a link from parent to child.

Use Move Field (207) on each field you wish to move. Test after each move.

Use Move Function (198) to move methods to the new child. Start with lower-level methods (those being called rather than calling). Test after each move.

Review the interfaces of both classes, remove unneeded methods, change names to better fit the new circumstances.

Decide whether to expose the new child. If so, consider applying Change Reference to Value (252) to the child class.

Example

I start with a simple person class:

class Person…

get name() {return this._name;}

set name(arg) {this._name = arg;}

get telephoneNumber() {return `(${this.officeAreaCode}) ${this.officeNumber}`;}

get officeAreaCode() {return this._officeAreaCode;}

set officeAreaCode(arg) {this._officeAreaCode = arg;}

get officeNumber() {return this._officeNumber;}

set officeNumber(arg) {this._officeNumber = arg;}

Here. I can separate the telephone number behavior into its own class. I start by defining an empty telephone number class:

class TelephoneNumber {

}

That was easy! Next, I create an instance of telephone number when constructing the person:

class Person…

constructor() {

this._telephoneNumber = new TelephoneNumber();

}

class TelephoneNumber…

get officeAreaCode() {return this._officeAreaCode;} set officeAreaCode(arg) {this._officeAreaCode = arg;}

I then use Move Field (207) on one of the fields.

class Person…

get officeAreaCode() {return this._telephoneNumber.officeAreaCode;}

set officeAreaCode(arg) {this._telephoneNumber.officeAreaCode = arg;}

I test, then move the next field.

class TelephoneNumber…

get officeNumber() {return this._officeNumber;} set officeNumber(arg) {this._officeNumber = arg;}

class Person…

get officeNumber() {return this._telephoneNumber.officeNumber;}

set officeNumber(arg) {this._telephoneNumber.officeNumber = arg;}

Test again, then move the telephone number method.

class TelephoneNumber…

get telephoneNumber() {return `(${this.officeAreaCode}) ${this.officeNumber}`;}

class Person…

get telephoneNumber() {return this._telephoneNumber.telephoneNumber;}

Now I should tidy things up. Having “office” as part of the telephone number code makes no sense, so I rename them.

class TelephoneNumber…

get areaCode() {return this._areaCode;} set areaCode(arg) {this._areaCode = arg;} get number() {return this._number;} set number(arg) {this._number = arg;}

class Person…

get officeAreaCode() {return this._telephoneNumber.areaCode;}

set officeAreaCode(arg) {this._telephoneNumber.areaCode = arg;}

get officeNumber() {return this._telephoneNumber.number;}

set officeNumber(arg) {this._telephoneNumber.number = arg;}

The telephone number method on the telephone number class also doesn’t make much sense, so I apply Rename Function (124).

class TelephoneNumber…

toString() {return `(${this.areaCode}) ${this.number}`;}

class Person…

get telephoneNumber() {return this._telephoneNumber.toString();}

Telephone numbers are generally useful, so I think I’ll expose the new object to clients. I can replace those “office” methods with accessors for the telephone number. But this way, the telephone number will work better as a Value Object [mf-vo], so I would apply Change Reference to Value (252) first (that refactoring’s example shows how I’d do that for the telephone number).

Inline Class

inverse of: Extract Class (182)

Motivation

Inline Class is the inverse of Extract Class (182). I use Inline Class if a class is no longer pulling its weight and shouldn’t be around any more. Often, this is the result of refactoring that moves other responsibilities out of the class so there is little left. At that point, I fold the class into another—one that makes most use of the runt class.

Another reason to use Inline Class is if I have two classes that I want to refactor into a pair of classes with a different allocation of features. I may find it easier to first use Inline Class to combine them into a single class, then Extract Class (182) to make the new separation. This is a general approach when reorganizing things: Sometimes, it’s easier to move elements one at a time from one context to another, but sometimes it’s better to use an inline refactoring to collapse the contexts together, then use an extract refactoring to separate them into different elements.

Mechanics

In the target class, create functions for all the public functions of the source class. These functions should just delegate to the source class.

Change all references to source class methods so they use the target class’s delegators instead. Test after each change.

Move all the functions and data from the source class into the target, testing after each move, until the source class is empty.

Delete the source class and hold a short, simple funeral service.

Example

Here’s a class that holds a couple of pieces of tracking information for a shipment.

class TrackingInformation {

get shippingCompany() {return this._shippingCompany;}

set shippingCompany(arg) {this._shippingCompany = arg;}

get trackingNumber() {return this._trackingNumber;}

set trackingNumber(arg) {this._trackingNumber = arg;}

get display() {

return `${this.shippingCompany}: ${this.trackingNumber}`;

}

}

It’s used as part of a shipment class.

class Shipment…

get trackingInfo() {

return this._trackingInformation.display;

}

get trackingInformation() {return this._trackingInformation;}

set trackingInformation(aTrackingInformation) {

this._trackingInformation = aTrackingInformation;

}

While this class may have been worthwhile in the past, I no longer feel it’s pulling its weight, so I want to inline it into Shipment.

I start by looking at places that are invoking the methods of TrackingInformation.

caller…

aShipment.trackingInformation.shippingCompany = request.vendor;

I’m going to move all such functions to Shipment, but I do it slightly differently to how I usually do Move Function (198). In this case, I start by putting a delegating method into the shipment, and adjusting the client to call that.

class Shipment…

set shippingCompany(arg) {this._trackingInformation.shippingCompany = arg;}

caller…

aShipment.trackingInformation.shippingCompany = request.vendor;

I do this for all the elements of tracking information that are used by clients. Once I’ve done that, I can move all the elements of the tracking information over into the shipment class.

I start by applying Inline Function (115) to the display method.

class Shipment…

get trackingInfo() {

return `${this.shippingCompany}: ${this.trackingNumber}`;

}

I move the shipping company field.

get shippingCompany() {return this._trackingInformation._shippingCompany;}

set shippingCompany(arg) {this._trackingInformation._shippingCompany = arg;}

I don’t use the full mechanics for Move Field (207) since in this case I only reference shippingCompany from Shipment which is the target of the move. I thus don’t need the steps that put a reference from the source to the target.

I continue until everything is moved over. Once I’ve done that, I can delete the tracking information class.

class Shipment…

get trackingInfo() {

return `${this.shippingCompany}: ${this.trackingNumber}`;

}

get shippingCompany() {return this._shippingCompany;}

set shippingCompany(arg) {this._shippingCompany = arg;}

get trackingNumber() {return this._trackingNumber;}

set trackingNumber(arg) {this._trackingNumber = arg;}

Hide Delegate

inverse of: Remove Middle Man (192)

Motivation

One of the keys—if not the key—to good modular design is encapsulation. Encapsulation means that modules need to know less about other parts of the system. Then, when things change, fewer modules need to be told about the change—which makes the change easier to make.

When we are first taught about object orientation, we are told that encapsulation means hiding our fields. As we become more sophisticated, we realize there is more that we can encapsulate.

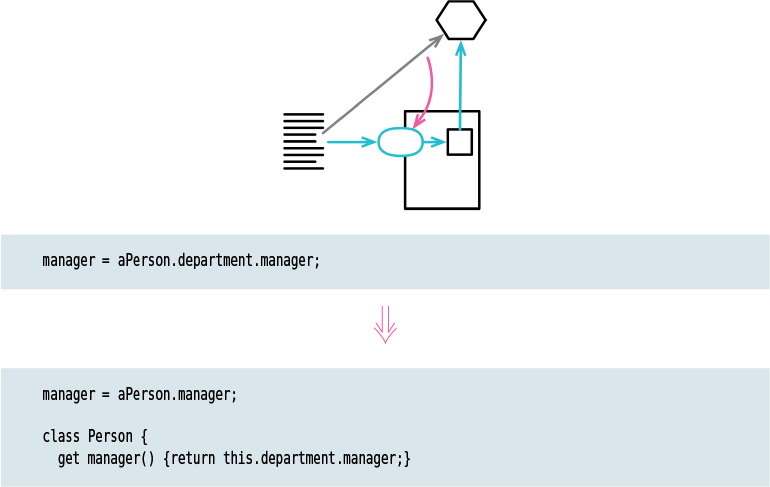

If I have some client code that calls a method defined on an object in a field of a server object, the client needs to know about this delegate object. If the delegate changes its interface, changes propagate to all the clients of the server that use the delegate. I can remove this dependency by placing a simple delegating method on the server that hides the delegate. Then any changes I make to the delegate propagate only to the server and not to the clients.

Mechanics

For each method on the delegate, create a simple delegating method on the server.

Adjust the client to call the server. Test after each change.

If no client needs to access the delegate anymore, remove the server’s accessor for the delegate.

Test.

Example

I start with a person and a department.

class Person…

constructor(name) {

this._name = name;

}

get name() {return this._name;}

get department() {return this._department;}

set department(arg) {this._department = arg;}

class Department…

get chargeCode() {return this._chargeCode;}

set chargeCode(arg) {this._chargeCode = arg;}

get manager() {return this._manager;}

set manager(arg) {this._manager = arg;}

Some client code wants to know the manager of a person. To do this, it needs to get the department first.

client code…

manager = aPerson.department.manager;

This reveals to the client how the department class works and that the department is responsible for tracking the manager. I can reduce this coupling by hiding the department class from the client. I do this by creating a simple delegating method on person:

class Person…

get manager() {return this._department.manager;}

I now need to change all clients of person to use this new method:

client code…

manager = aPerson.department.manager;

Once I’ve made the change for all methods of department and for all the clients of person, I can remove the department accessor on person.

Remove Middle Man

inverse of: Hide Delegate (189)

Motivation

In the motivation for Hide Delegate (189), I talked about the advantages of encapsulating the use of a delegated object. There is a price for this. Every time the client wants to use a new feature of the delegate, I have to add a simple delegating method to the server. After adding features for a while, I get irritated with all this forwarding. The server class is just a middle man (Middle Man (81)), and perhaps it’s time for the client to call the delegate directly. (This smell often pops up when people get overenthusiastic about following the Law of Demeter, which I’d like a lot more if it were called the Occasionally Useful Suggestion of Demeter.)

It’s hard to figure out what the right amount of hiding is. Fortunately, with Hide Delegate (189) and Remove Middle Man, it doesn’t matter so much. I can adjust my code as time goes on. As the system changes, the basis for how much I hide also changes. A good encapsulation six months ago may be awkward now. Refactoring means I never have to say I’m sorry—I just fix it.

Mechanics

Create a getter for the delegate.

For each client use of a delegating method, replace the call to the delegating method by chaining through the accessor. Test after each replacement.

If all calls to a delegating method are replaced, you can delete the delegating method.

With automated refactorings, you can use Encapsulate Variable (132) on the delegate field and then Inline Function (115) on all the methods that use it.

Example

I begin with a person class that uses a linked department object to determine a manager. (If you’re reading this book sequentially, this example may look eerily familiar.)

client code…

manager = aPerson.manager;

class Person…

get manager() {return this._department.manager;}

class Department…

get manager() {return this._manager;}

This is simple to use and encapsulates the department. However, if lots of methods are doing this, I end up with too many of these simple delegations on the person. That’s when it is good to remove the middle man. First, I make an accessor for the delegate:

class Person…

get department() {return this._department;}

Now I go to each client at a time and modify them to use the department directly.

client code…

manager = aPerson.department.manager;

Once I’ve done this with all the clients, I can remove the manager method from Person. I can repeat this process for any other simple delegations on Person.

I can do a mixture here. Some delegations may be so common that I’d like to keep them to make client code easier to work with. There is no absolute reason why I should either hide a delegate or remove a middle man—particular circumstances suggest which approach to take, and reasonable people can differ on what works best.

If I have automated refactorings, then there’s a useful variation on these steps. First, I use Encapsulate Variable (132) on department. This changes the manager getter to use the public department getter:

class Person…

get manager() {return this.department.manager;}

The change is rather too subtle in JavaScript, but by removing the underscore from department I’m using the new getter rather than accessing the field directly.

Then I apply Inline Function (115) on the manager method to replace all the callers at once.

Substitute Algorithm

Motivation

I’ve never tried to skin a cat. I’m told there are several ways to do it. I’m sure some are easier than others. So it is with algorithms. If I find a clearer way to do something, I replace the complicated way with the clearer way. Refactoring can break down something complex into simpler pieces, but sometimes I just reach the point at which I have to remove the whole algorithm and replace it with something simpler. This occurs as I learn more about the problem and realize that there’s an easier way to do it. It also happens if I start using a library that supplies features that duplicate my code.

Sometimes, when I want to change the algorithm to work slightly differently, it’s easier to start by replacing it with something that would make my change more straightforward to make.

When I have to take this step, I have to be sure I’ve decomposed the method as much as I can. Replacing a large, complex algorithm is very difficult; only by making it simple can I make the substitution tractable.

Mechanics

Arrange the code to be replaced so that it fills a complete function.

Prepare tests using this function only, to capture its behavior.

Prepare your alternative algorithm.

Run static checks.

Run tests to compare the output of the old algorithm to the new one. If they are the same, you’re done. Otherwise, use the old algorithm for comparison in testing and debugging.