2 History and Purpose of Copyright

In this chapter, we will be looking at remixing and its history of moving ideas and creativity forward. Please note that although fair use and copyright are discussed as legal concepts in this chapter, this book is not a legal resource in and of itself. For further information about fair use and copyright law, please refer to the various resources referenced throughout the book and in the appendices.

Whether it is children imitating sounds as they learn their native language, or adults copying bits and pieces of pop culture as they spread memes, catch phrases, or pieces of songs, people can learn by copying. Artist Elisabeth Condon speaks on this issue in her interview (see Appendix A), making note of Chinese traditions of copying as valued learning methods, in contrast with western approaches that value originality.

It should be no surprise then that artists of all kinds, from writers and musicians to visual artists and designers, routinely appropriate or incorporate the work of others—either in full or in part—into their own creative work, and have done so for centuries. This process often has many different names, from sampling, remixing, and recontextualizing, to juxtaposing or recombining. Artist Guen Montgomery emphasizes the importance of remixing in her interview (see Appendix A) when she states (Figure 2.1),

Like most artists I subconsciously borrow from the things I’ve seen, sometimes without realizing that I am picking up things here and there. I also remix my own work – one idea will sprout an offshoot that feels new but borrows conceptually or visually from past works.

In fact, it is very common for an artist’s first pieces to be mimicry of works they admire. The master copy, which is the act of replicating a master work as closely as possible, has been an art school assignment for centuries. Recent advances in technology have further helped artists to borrow and incorporate the work of others, which has made remixing more commonplace now than ever.

Figure 2.1 Justine Fox, Untitled (2010) Charcoal and graphite, approximately 8" x 10", master copy of Frank Magnotta for Intermediate Drawing. © Justine Fox. Color image available at accompanying website - http://RemixingAndDrawing.com.

The widespread use of remixing in the arts has developed alongside cultural appropriation, sometimes also known as cultural misappropriation, which is the process of an individual from a powerful and dominant culture adopting elements from a culture systematically oppressed by the dominant culture. Cultural appropriation involves a power imbalance, as the person doing the appropriating can profit from their creation, while the oppressed people get little or, more often, no compensation. For example, there is a long history of colonialist appropriation, where colonizers in foreign countries take a piece of folk culture—collectively created over generations—and denies local authorship while profiting from the appropriation. An example of this type of cultural appropriation often happens in relation to Native American designs, which are appropriated by non-Native American interior designers and fashion designers for profit. This form of appropriation ignores the difference in power between the privileged designers and marginalized indigenous people. Race, gender, power, globalization, and other markers of privilege and difference must always be taken into consideration when evaluating an appropriation case. Privilege is discussed in more detail in Chapter 4.

As artists, it is important to strive to avoid cultural appropriation and its power abuses. It is also important to note the terminology used here can be confusing because the word appropriation is a part of the phrase. In some contexts, the word appropriation is used to mean “borrowing” or “using without permission” without implying ties to a power imbalance. As we will discuss in our chapter on fair use, there are guidelines for using work without permission; however, cultural appropriation—where there is a power imbalance—is not acceptable. To summarize, anytime you encounter the word appropriation, be sure to ask yourself if a power imbalance is in place.

Certain concepts are often associated with remixing. For example, many artists use remixing to critique consumer culture, reach a wider audience, or to question the idea of originality. We can trace these critical ideas, as well as remixing throughout all forms of art, music, and writing, from the early 1900s to the present using the following timeline.

Note that while this timeline begins in 1900, remixing has been employed by artists for centuries. For example, more than 1000 years ago, the residents of Cacaxtla, a small city-state in Mexico, created a series of murals that looked very much like Maya art from 400 miles to the south. Researchers propose the artists from Cacaxtla appropriated and remixed this imagery as they interacted with traders.1 Similarly, nineteenth-century Chinese artists appropriated and remixed imagery of partial book pages, burned paintings, and other fragments of papers in bapo, a form of painting visually similar to collage.

Timeline 2.1 Remixing, and the Tools that Made It Possible since 1900

NOTE: For a fully illustrated timeline, please visit the accompanying website: http://RemixingAndDrawing.com

1906–1919—Cubism: An art movement that purposefully ignores the traditions of perspective and naturalistic representation through a variety of tactics, including showing multiple views of a subject simultaneously. Two cubist artists, Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, are credited with developing what we now know as collage, which is the act of combining a variety of materials, not just art supplies, to create compositions. An example is Picasso’s Still Life with Chair Caning (1912).

1920s—The Jazz Age. Jazz music includes standards that are performed again and again by many different ensembles, and improvised jazz solos often navigate towards recognizable melodies, too.

1915–1924—Dada: An art movement focused on anti-war and anti-materialistic middle-class ideas. These artists worked in a wide variety of media from performance to poetry, photography, sculpture, and more. Dada is important to remix culture because it resulted in the readymade, which is a manufactured non-art object that is altered, perhaps only slightly, to reframe it as an artwork. Marcel Duchamp created some of the first readymades, his most famous being a urinal on its side, titled Fountain (1917). Dada also helped create the photomontage, which is a composite photograph made of various other photographs that have been cut and pasted to create a new composition. Hannah Höch’s Das schöne Mädchen [The Beautiful Girl] (1920) is an example of photomontage. Dada artists Tristan Tzara and Kurt Schwitters also pioneered early cut-up methods by cutting the words from World War I propaganda and rearranging them by chance, rendering them nonsensical.2

1928—Magnetic tape was invented for recording sound by Fritz Pfleumer in Germany. This was a vital step towards remixing because it allowed for cutting and rearranging pieces of sound, whereas previous audio recording technologies, such as wax cylinders or vinyl records, were not able to be physically remixed in this way.

1930s—American folk singer Woody Guthrie appropriated common and recognizable folk melodies and changed the words to fight for workers’ rights.

1935—The first audio recorder using magnetic tape, the Magnetophone K1, was debuted at the Berlin Radio Fair in August.3 This invention allowed remixers to incorporate their own sounds, rather than being restricted to prerecorded sounds.

1940s—Musique concrete develops as a way of constructing music by mixing recorded sounds. Pierre Schaeffer, an engineer, radio announcer, and originator of work in this vein, created pieces such as etude aux chemins de fer (1948).

1942—Artist Joseph Cornell creates Homage to the Romantic Ballet, one of many box-based assemblages that built three-dimensionally upon collage traditions.

1955–1959—Robert Rauschenberg’s Monogram is an example of the three-dimensional assemblages, also known as Combines, that built on the tradition of collage.

1959—Twenty-one years after Chester Carlson invented xerography, the first convenient office copier using xerography was unveiled, the 914 copier by Xerox. This invention would lead to the development of zine culture (pronounced /zēn/). Zines are self-published, small-circulation magazines or books that often contain original and/or appropriated text and images reproduced via photocopier. Zines often deal with controversial or niche topics that could be challenging to publish via traditional means.

1950s–1970s—Pop Art: An art movement focused on bringing images from pop culture and mass media into artworks in order to challenge mass consumption of everyday culture. Andy Warhol’s soup cans works showcased Campbell’s canned soup branding as the artwork itself. Richard Hamilton’s collage, Just What Is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, So Appealing? (1956) features a Tootsie Pop, a vacuum cleaner ad, and a canned ham, among other commercial imagery.

1950s–1970s—Artist Henry Darger created a massive collection of drawings and paintings using a number of collage, tracing, and copying approaches. An example of his work is Untitled (At Jennie Richee, they admire the beauty of the tropical nimbus clouds), [no date].

1957–1972—Situationism: An art movement founded by Guy Debord and focused on critiquing capitalism. A key element of situationism was détournement, or the adoption of prevalent words and images from dominant culture and turning them against the system. Debord describes this concept and more in his book, Society of the Spectacle.

1961–1964—Beat writer William S. Burroughs adapted the Dada cut-up approach and published The Nova Trilogy. The first novel in this series, The Soft Machine, is considered his most recognized cut-up work. The Beat Generation of writers met near the end of World War II and was interested in questioning mainstream politics and culture, changing consciousness, and defying conventional writing.

1963—A group of artists in Germany—Gerhard Richter, Sigmar Polke, Wolf Vostell, and others—co-founded Capitalist Realism, a movement inspired by the imagery in newspapers and magazines and influenced by Pop Art in America.

1964—The first VCR for the home was released by Sony. This was a step towards allowing artists to record and view original footage for remixing outside of expensive professional recording studios.

1970—Artist Cildo Meires covertly launched his appropriation work Insertions into Ideological Circuits by stamping subversive messages onto banknotes and Coca-Cola bottles, then putting them back into circulation, thereby sharing his messages with people he would not otherwise reach.

1973—The first Xerox Alto computers were released non-commercially for use at various Xerox labs and some universities. This was the first computer to support an operating system based on a graphical (screen-based) user interface (GUI). Its GUI inspired Apple to develop computers that would eventually lead to the massive popularity of personal computing. Putting computers in the home helped remixing become an everyday phenomenon.

1970s—Punk Movement: A musical and cultural movement that borrowed détournement and other subversive political pranks. One of the well-known images of this movement is the Sex Pistol’s God Save the Queen cover art from 1977.

1977—The first commercially available digital audio recorder, the Sony PCM-1, was released, making audio remixing even more accessible to artists.

1977—Curator Douglas Crimp’s “Pictures” exhibition at Artists Space featuring Troy Brauntuch, Jack Goldstein, Sherrie Levine, Robert Longo, and Philip Smith focused on appropriation from photography via mass media, such as newspapers and magazines.

1978—All expression is declared copyrighted from the moment it is reduced to tangible form (ideas cannot be copyrighted)

1979—Sugarhill Gang releases “Rapper’s Delight,” which borrows the bass riff from Chic’s “Good Times.” This is one early example of remixing in hip hop music.

Early 1980s—Artist Barbara Kruger begins making her iconic collaged works that juxtapose words and photos, which question the media’s construction of women as consumers and shoppers.

1980s—Culture Jamming: A term coined by Don Joyce, of the sound collage band Negativland, describing a tactic used to subvert or critique political and advertising messages and promote progressive change, closely related to situationism and détournement. The process critiques mass media, such as magazine advertisements or billboards, and often involves using the original medium’s communication method to create satirical statements. Famous culture jammers include the Billboard Liberation Front and Adbusters.

1987—Public Enemy, a rap group known for their use of sampling, or including clips from other musical works which are repeated and / or rearranged, releases their debut album, Yo! Bum Rush the Show.

1987—Artist Mike Kelley creates one of his most well-known works More Love Hours Than Can Ever Be Repaid and The Wages of Sin, which consists of an assemblage of stuffed fabric toys and handmade afghans from thrift stores on canvas with dried corn and accompanied by wax candles on a table. This work remixes cast-off items to create a representation of time spent in caring for another human being.

1993—Artist Douglas Gordon creates 24 Hour Psycho, a video work that appropriates the entire film of Psycho and slows it down to last 24 hours.

1993—The Yes Men, a two-person collaboration between Mike Bonanno and Andy Bichlbaum, create the Barbie Liberation Organization, which purchased Barbie and G.I. Joe toys and switched their voice boxes. They then covertly placed the toys back in stores for purchase.

1997—Artist Glenn Ligon appropriates text from a 1953 James Baldwin essay to create a series of text-based paintings entitled Stranger in the Village.

1998—The Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) was signed into law. This act stated that internet service providers were vulnerable to prosecution if they didn’t take down content that copyright owners complained about, regardless of whether the work falls under the category of fair use. A counter claim can be filed, but it can take months to get content re-posted.

2004—Kanye West, now well-known for sampling and remixing in hip hop music, debuts his first album, The College Dropout, which pulls samples from songs such as “Mystery of Iniquity,” by Lauryn Hill; “Distant Lover,” by Marvin Gaye; “(Don’t Worry) If There’s a Hell Below, We’re All Going to Go,” by Curtis Mayfield; and “A House is not a Home,” by Luther Vandross, among others.

2006—Artist Steve McQueen appropriates the images of British soldiers killed in the Iraq war for a work titled Queen and Country, which consists of sheets of unofficial postage stamps featuring this imagery.

2009—Artist Shepard Fairey is legally challenged by the Associated Press (AP) over the ownership of the original photo Fairey appropriated for his Hope (2008) poster. Fairey and his attorney claimed that the image was protected under fair use; the AP argued that the copyright of the photo was owned by the original photographer. A settlement was reached between Fairey and the AP in 2011.

2014—Richard Prince debuts his New Portraits exhibition at the Gagosian gallery in London. The exhibit consists of entirely of the Instagram photos taken by others and used without their permission. Prince’s only alteration is the addition of comments beneath each picture. Multiple subjects of the photos have filed suit against Prince.

These remixing practices continue to be vital to contemporary artists in all media. As you read through the examples cited in this text, and any referenced articles and videos, be sure to return to the timeline to see what other things were happening around the same time. This sense of context can help readers to more thoroughly understand remixing’s development.

Exercise 2.1 Build the Timeline

Find three more works using remixing to add to the timeline. Present images of these three works and share information on how the work utilizes remixing. As a class, compile all your timeline additions in chronological order to view how the timeline has grown.

The processes of copying, integrating, reusing, collaging, and changing is necessary for innovation, creativity, and culture to grow. Through this process of remixing, we can reinterpret and question existing works while producing new art. On some scale, all art is an act of remixing because no artist can produce new works without being influenced by their life experiences and the works—commercial, cultural, artistic, political, etc.—they have seen in the past. In fact, there are many instances of artists and other inventors arriving at similar ideas at almost the same time, despite having no contact with one another. Here is a blog devoted to such cases: http://who-wore-it-better.tumblr.com/. In some situations, one artist might be copying the other, but in many cases, the works were created without each other’s knowledge.

Exercise 2.2 Three Appropriated Elements

Select a well-known drawing and identify at least three clear, visual elements that might have been appropriated. Think in terms of subject, form, content, and context.

As a reminder, the subject is what the artist is portraying such as people, places, and things. The form is the sensorial experience of the work (how does it look, sound, smell, taste, and feel), and includes the media as well as the arrangement of the compositional elements. The content is the meaning or impact of the work, which is created through the intersection of subject, form, and context. Context is the set of factors surrounding the creation and display of the work, and it can include a wide range of elements such as age, class, race, gender identity, sexual identity, geographic location, religion, culture, political affiliation, and so on.

You will likely have to do some research and may end up finding connections not only to other artists, but also to movies, books, and online sources. Report back to the class to examine the variety of approaches taken by different artists.

Often as an artist is creating, there will be intersections with imagery that falls under copyright. It is important to understand why copyright exists, and how it continues to evolve.

Thomas Jefferson considered copyright a necessary evil, in that he favored providing just enough incentive to create, and nothing more, allowing ideas to flow freely.4 It was assumed that people other than the original creator would be able to do a better job developing upon or furthering an idea or work, thereby leading to the advancement of culture as a whole.

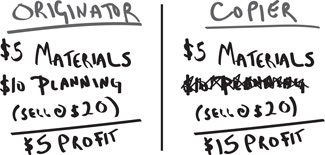

Thus, the original goal of US copyright law, passed in 1790, was to ensure knowledge and culture were spread and promoted. Lawmakers proposed establishing an active and diverse public domain, which is the collection of works not protected by copyright that can be used and built upon by other thinkers and creators. Originally, the law’s primary beneficiary was the public, and it acknowledged the importance of copying, combining, and changing as vital to the development of a dynamic and inventive society. The law struck a deal with creators by granting them the sole rights to their work for a short amount of time—14 years, which could be renewed for fourteen more (twenty-eight in total) if the creator was still alive. These rights encouraged creation and invention by allowing creators to have a short-term monopoly on their creation, thereby profiting from their ideas long enough to cover any startup costs (Figure 2.2). This short-term profit for creators was not the main purpose of US copyright law. Instead, these limited profits were meant as encouragement “to promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts.”

However, over time there have been alterations to copyright law to change the beneficiary from the public as a whole to the individual creator or, in many cases, large corporations and distributers. This phenomenon is practiced by some of the largest and most familiar corporations. For example, the Disney Corporation has appropriated content from a wide variety of sources to create their own animations, but have regularly fought legal battles against other artists incorporating Disney imagery into their own work, such as Dennis Oppenheim or Dan O’Neil. Disney has legally extended their copyright on Mickey Mouse—which was recently scheduled to expire in 1984—to 2023.5 Similarly, Steve Jobs of Apple was very open about appropriating features to make his various successful products, stating in the documentary Triumph of the Nerds, “We have always been shameless about stealing great ideas.” However, he became fiercely defensive when others appropriated from his works. In reference to Google’s Android-based phones, a competitor to the Apple iPhone, he said,

I will spend my last dying breath if I need to, and I will spend every penny of Apple’s $40 billion in the bank, to right this wrong. I’m going to destroy Android, because it’s a stolen product. I’m willing to go thermonuclear war on this.6

Through these examples, one sees loss-aversion, where creators feel it is ok to copy others, but not ok for others to copy what they created. This leads to a lack of acknowledgement of remixing’s role in developing new works (Figures 2.3 and 2.4).

Due to loss-aversion and these profit-oriented interests, both the length and breadth of copyright has been extended. Currently, there is no registration requirement, and any creative act in tangible form is now protected by copyright, including emails, texts, or children’s drawings. These changes have limited the public’s ability to build on works of the past. The current term of copyright is the life of the author plus 70 years, or if it is a work of corporate authorship, 95 years from publication or 120 years from creation, whichever expires first, which is significantly longer than the original term of 14–28 years. Monopolies such as these are counter to the public interest, as they limit the development of the public domain. As Lethem states, “Whether the monopolizing beneficiary is a living artist or some artist’s heirs or some corporation’s shareholders, the loser is the community, including living artists who might make splendid use of a healthy public domain.”7

As the duration of copyright has expanded, so too has the concept of intellectual property, which implies that our culture is a market and everything of value should or can be owned by someone. Under the guise of intellectual property, Girl Scouts have been asked to pay royalties for singing songs such as “Puff the Magic Dragon” and “Over the Rainbow” around a campfire, corporations filed for patents for human gene sequences, and only since December 2015 have movie-makers been allowed to use one of the best-known songs in the world “Happy Birthday” (1893), without paying royalties. As society continues to intensify its belief in private ownership, it is the responsibility of its citizens to remain vigilant and call out attempts to disadvantage the greater good for the financial benefit of the few. This was the case with “Happy Birthday”—the lawsuit was filed in 2013 by musicians and film-makers who were billed for using the song, and two years later it was found that the music publisher did not own the song, but only some musical arrangements and therefore could not charge for its use.

Of course, individual artists also rely on copyright to generate their income, which is a positive application of the law. Having work copied can be financially harmful to the original artist, as in multiple cases of large corporations stealing work from independent artists. It is important to point out that copyright makes sense for individuals over a relatively short amount of time (14–28 years), but for large corporations and artists’ heirs—whose interest is in distributing rather than producing new creative goods—copyright becomes a tool of profit, rather than a tool to promote the creation and spread of new works, which was the original intent of the copyright and patent acts of 1790. This challenge is fixable; copyright is a continually renegotiated and imperfect idea. Just as it has been moved towards a more profit-centered system, it can also be steered towards embracing copyright’s original goal, ensuring knowledge and culture are promoted and spread. Regardless, there are multiple ways to work within the current copyright system. Read more in the section on Fair Use and Creative Commons Licenses.

Notes

1 Allen, Susie. “Mexican Murals Reveal Art’s Power,” University of Chicago. Accessed August 5, 2017. www.uchicago.edu/features/mexican_murals_reveal_arts_power/.

2 McLeod, Kembrew and Rudolf Kuenzli. Cutting Across Media: Appropriation Art, Interventionist Collage, and Copyright Law. Duke University Press, 2011.

3 Steven Schoenherr, Steven. “The History of Magnetic Recording,” Audio Engineering Society, 2002. Accessed September 30, 2016. www.aes.org/aeshc/docs/recording.technology.history/magnetic4.html.

4 Lethem, Jonathan. “The Ecstasy of Influence.” Harper’s Magazine, February 2007.

5 Schlackman, Steve. “How Mickey Mouse Keeps Changing Copyright Law,” Art Law Journal. Accessed September 24, 2016. http://artlawjournal.com/mickey-mouse-keeps-changing-copyright-law/.

6 Jobs, Steve. “I’m going to Destroy Android, Because It’s a Stolen Product.” Accessed September 4, 2016. www.dailytech.com/Steve+Jobs+Im+Going+to+Destroy+Android+Because+Its+A+Stolen+Product/article23077.htm.

7 Lethem, Jonathan. “The Ecstasy of Influence.” Harper’s Magazine,February 2007.