CHAPTER 10

Issues Management

Plan for what is difficult when it is most easy, do what is great while it is small. The most difficult things in the world must be done while they are still easy, the greatest things in the world must be done while they are still small.

(Lao Tzu [604–581 bc], The Tao-Te Ching, or The Way and Its Power)

10.1 Issues Management Overview

10.3 Developing an Issues Management Plan

10.4 What the Elements of the Issues Management Analysis and Planning Template Mean

10.5 The Issue Management Plan

10.6 The Difference between Issue Management Strategies and Tactics (Actions to Take)

10.7 Ultimate Audience/Influencer Audience

10.9 Questions for Further Discussion

10.10 Resources for Further Study

■ ■ ■

The peanut allergy is one of the most serious and dangerous food allergies a person can have. A severe allergy to peanuts can cause anaphylaxis, a potentially fatal allergic reaction if not treated quickly.

The number of children diagnosed with this allergy has been steadily increasing for years. A 2017 study found that the number of children reported to have a peanut allergy has increased 21% since 2010.1

In February 2016, a new study uncovered groundbreaking information about how to prevent peanut allergies in children. According to the “Learning Early About Peanut Allergy (LEAP)” study, which became the most-read story ever in the New England Journal of Medicine, the development of the peanut allergy in children can be reduced by up to 86% by introducing peanut-containing foods to infants as early as 4 to 6 months of age.2 This new protocol for introducing infants to peanut-containing foods earlier had the potential to be a game changer in the food allergy field, as well as for the peanut industry.

The challenge, then, became how to disseminate this information to parents of young children, many of who would likely be anxious about introducing their infant children to peanuts given the seriousness of a peanut reaction. The National Peanut Board (NPB) and the PR agency Golin, in partnership with the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology and the Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Connection Team, launched a multiyear campaign to build awareness to this new research among parents and to inspire them to follow this new protocol. The key to the campaign was to deliver this message through people that parents would relate to and find reliable.

Justin Baldoni, an actor best known for his role as Raphael Solano on Jane the Virgin and a recent father, fit the bill. In a three-part video series Baldoni described his own journey of tackling the tough decisions of parenthood and why and how he introduced his infant son, Maxwell, to peanut-containing foods. Baldoni’s videos, as well as all of the campaign materials tailored for parents, were made easily available on PreventPeanutAllergies.org. People.com shared Baldoni’s videos, and so did other parenting and allergy publications. Online foodie, parenting and lifestyle influencers were also lined up to follow Baldoni’s videos in sharing their own experiences of introducing peanut-containing foods to their children, and even their favorite peanut-containing food recipes for infants and toddlers. And an online toolkit of promotional campaign resources was released to campaign partners and supporters to share on their channels in advance of Food Allergy Awareness Week.3

According to NPB and Golin, Baldoni’s videos alone generated more than 6.1 million views across Instagram, Twitter and Facebook, as well as 155 million earned media impressions, far exceeding the campaign’s goal of 2 million total views. Additionally, 67% of those exposed to the campaign agreed that peanut-containing foods are safe to feed to children less than 12 months old and 56% of people exposed to the campaign said they intended to introduce peanut foods to their children before 12 months, exceeding the campaign’s goals on both counts.4

The National Peanut Board and Golin received an Award of Excellence in the Issue Management Category from the Public Relations Society of America. By taking the initiative to share this new protocol and engage with parents directly as agents of change, NPB and Golin have now made it more likely that fewer children will develop this life-threatening allergy.

■ ■ ■

10.1 Issues Management Overview

Issues management is a corporate process that helps organizations identify challenges in the business environment.

Before they become crises.

Issues management is a corporate process that helps organizations identify challenges in the business environment—both internal and external—before they become crises and mobilizes corporate resources to help protect the company from the harm to reputation, operations, and financial condition that the issue may provoke. Issues management is a subset of risk management, but the risks it deals with are public visibility and reputational harm.

Enlightened companies have formal issues management processes, at both the enterprise-wide level and in individual business units or geographically defined operations. Sometimes the corporate communication department runs the function, but often the function is run from the legal, quality assurance, government relations or risk management departments.

Wherever issues management may reside in an organization, typically it is an interdisciplinary function.

Wherever issues management may reside in an organization, typically it is an interdisciplinary function involving multiple corporate perspectives and several communication functions.

There is often meaningful overlap among issues management, government relations, public relations, law and other corporate functions. And there is a strong relationship between issues management and crisis management: Issues management can be seen as a subset of crisis management that anticipates and manages long-duration crises that are chronic, in order to anticipate and mitigate harm before the issue explodes into a full-blown crisis. Or as some have said, “Manage the issue so that you won’t have to manage a crisis.”

10.1.1 Establishing the Issues Management Function

A formal issues management function involves establishing a multidisciplinary issues management team consisting of all major business functions.

Every company’s issues management structure should align with its business operations, marketplace realities and leadership styles.

Every company’s issues management structure should align with its business operations, marketplace realities and leadership styles. But as a general principle, the most effective issues management structures have several elements in common. They adapt these elements to their unique circumstances and needs.

Figure 10.1 is a diagram of a typical issues management structure.

The elements of a typical issues management structure are:

That governance structure is responsible for review and approval of major recommendations.

Is a standing group of people who represent core functional areas across the organization.

- 1. Governance. There needs to be some senior body to whom the standing issues management team reports. That governance structure is responsible for review and approval of major recommendations and plans; identification and assignment of resources to manage issues; and supervision of the work of the issues management team.

- 2. Issues management team. This is a standing group of people who represent core functional areas across the organization (e.g., legal, manufacturing, human resources, public relations, marketing/advertising, sales, security, administration, information technology). It meets on a set schedule, and also whenever a pressing or breaking issue warrants.

- The duties of the issues management team include:

- Establishing procedures for consistent assessment of issues, planning for managing the issues, and communicating about events or decisions regarding those issues.

- Serving as the eyes and ears within the company and among stakeholders outside the company.

- Developing an issues agenda and working through that agenda in a systematic fashion.

- Naming individual issue champions to have authority to develop plans and documents on particular issues, to then be reviewed by the entire team. Each issue champion heads a topic-specific task force (see later).

- Serving as a central clearing house for any issue that may threaten the company’s reputation.

- Managing the approval process for communications about any particular issue.

- 3.

Topic-specific task forces. Topic-specific task forces are groups of employees tasked with developing understanding of a particular issue or set of issues. The task forces are typically led by a member of the issues management team who has been designated the issue champion for that task force.

The task forces can be assigned based on geography, on functional area, on kind of threat (e.g., litigation) or by any other criteria that the issues management team determines. Each task force reports to the issues management team. - 4. Issues resource team. The issues resource team serves as a group of predesignated experts in particular functional areas who can be harnessed by either the issues management team or by the topic-specific task forces as needed. They may include lawyers, communicators, IT professionals, administrative personnel or members of particular business units. They are not a standing structure, but rather a group of individuals who may be brought into particular issues as needed.

The issues resource team serves as a group of predesignated experts in particular functional areas who can be harnessed by either the issues management team or by the topic-specific task forces as needed.

Initial tasks for the issues management team include identifying issues that matter to the company.

Initial tasks for the issues management team include identifying issues that matter to the company. Typical issues are:

- Possible legislative activity impacting the company, its competitors, its products, its pricing or its marketplace.

- Regulatory events and changes to the business climate. For example, between 2001 and 2005 there were significant changes in the regulatory climate in the United States for the public accounting, investment banking, pharmaceuticals and insurance industries. After the 2008 financial crisis, there was a new round of legislative and regulatory activity affecting companies in a broad range of industries.

- Changes in social trends that make previously accepted practices unacceptable. After a number of prominent men were discovered to have sexually harassed, assaulted or otherwise abused women with whom they worked, the #MeToo movement arose. This dramatically changed the expectations of appropriate relations among genders in the workplace, and caused many organizations to review their own procedures, practices and vulnerabilities.

- Competitors’ activities, both positive and negative.

- Lawsuits, including class action lawsuits where a large number of people claim to have been harmed by a company’s products or business practices.

- Product quality and safety issues, especially issues that require the recall of defective products or put customers’ lives, health, safety or financial condition at risk.

- Internal problems, such as the need to restate earnings or change accounting treatment of previously disclosed earnings.

- Activities by groups, public officials or candidates for public office with agendas that pose a risk to organizations.

10.1.2 Prioritizing Issues

Once an issue is identified, it is important to understand how significant it is and what corporate resources will be needed to manage the issue effectively.

Once an issue is identified, it is important to understand how significant it is and what corporate resources will be needed to manage the issue effectively.

The two critical factors in assessing the importance of an issue are likelihood (how likely is it that this issue will play out to the company’s disadvantage) and magnitude (if it does play out to our disadvantage, how significant could the harm be).

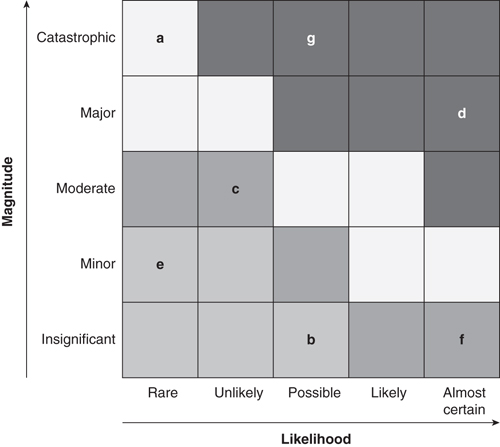

Any given issue can be measured on a magnitude/probability matrix (see Figure 10.2).

The farther up and to the right on the chart, the more compelling the issue. The upper right contains issues with high magnitude and high likelihood; the upper left, issues with high likelihood and low magnitude; the lower right, low likelihood and high magnitude; and the lower left for issues where both magnitude and likelihood are low.

High likelihood/high magnitude issues would get primary attention.

Multiple individual issues can be plotted on this matrix, which functions as a tool to allocate resources and management attention to a given issue. High likelihood/high magnitude issues would get primary attention. Various scenarios of how a single issue might play out can also be plotted on the matrix to help give a sense of the relative resources required to manage an issue in dynamic circumstances. Multiple issues, represented in Figure 10.3 with individual letters, can be plotted to help the issues management team prioritize its work based on the relative magnitude/probability of each issue.

If an issues management team considered a range of issues plotted on the graph in Figure 10.3, it would focus most of its attention and resources on the two issues in the upper right portion, issues g and d. Second, it would appraise the single issue with high likelihood but low magnitude, issue a; and the two issues with moderate magnitude/probability or high probability but low magnitude, issues c and f. The two issues where both magnitude and probability are low, issues e and b, would be put on a watch list and periodically reviewed.

For each issue identified, the issues management team would next develop a plan to analyze it, allocate resources to influence events to lessen its impact and engage stakeholders in support.

For each issue identified, the issues management team would next develop a plan to analyze it, allocate resources to influence events to lessen its impact and engage stakeholders in support.

10.1.3 Issues Management Planning Process

In general terms, the planning process for issue management is similar to the public relations process described by Grunig and Hunt and others.5

Typical steps are as follows:

Formula for Issues Management Success

Three first steps

- Establish a mechanism (e.g., regularly scheduled meetings, ongoing research, periodic discussion with key stakeholders) to identify potential issues crises before they occur.

- Prepare background documents and analysis. The longer the document, the more important the executive summary.

- Empower the communications team to advocate with lawyers, business heads, and company members who might not see the connections between discrete issues and the business interests of the enterprise.

Develop an action plan

- Develop an issues management and communication plan with objectives, strategies, tactics, messages, budgets, timelines and an evaluation mechanism.

Enlist or adapt the current communications program

- Aggressively manage the communication program.

Evaluate and review

- Periodically assess results.

Case Study 1

In early 2000, one of the largest financial services companies in the United States faced a significant business challenge. It had recently lost a major lawsuit; had some serious regulatory setbacks; and was on the receiving end of wave after wave of negative scrutiny, from regulators to customers to the news media to its own employees. It was the subject of major class-action lawsuits and also of major investigative reports on prominent television investigative news programs. And as challenges arose, the company suffered meaningful self-inflicted harm.

Because it didn’t have a mechanism to prioritize and coordinate communication around the many challenges it faced, different parts of the company took it upon themselves to communicate—but in ways that were inconsistent with what other parts of the company did. The company also let many challenges go unaddressed, giving its adversaries the upper hand. It needed two different kinds of help. First, immediate crisis response capacity (see Chapter 11). But more important, it needed to take a holistic view of the issues it faced, the resources it deployed, the stakeholders who mattered, and the ways those issues were managed.

As a first step the company created a standing issues management team, drawing two representatives each from the major business functions (law, communication, sales, administration, human resources, business development) and one each from ancillary function (research, operations, compliance, security). The team was charged with coordinating the issues management function across the enterprise, and all other business areas were told to stop attempting to manage issues ad hoc. The issues management team then was trained in the use of the Issues Management Template (see Section 10.3.2), and also in best practices in communicating internally and externally. In the first year, the issues management team met daily for several hours. In the course of the year, it identified and began to manage 153 discrete issues of varying degrees of complexity and significance. In that year it successfully resolved dozens of outstanding difficult issues.

Over time, as the issues management team became better at managing issues, and as the company stopped suffering self-inflicted harm, adversaries became less aggressive in pursuing their own advantage at the company’s expense. And as members of the issues management team rotated off the team and were replaced by others, the business units became populated with issues-sensitive executives who could identify challenges early and refer them to the issues management team for consideration.

In 2019 that company’s issues management team was still in operation—after more than 15 turnovers of team members—and the company has seen significant improvement in its competitive position. And it has gone from one of the least capable to one of the most capable companies in issues management in the financial sector. The keys were discipline, perseverance and continuous learning.6

Case Study 2

As consumer electronics become ubiquitous in American homes, a growing but underappreciated danger arose: The tendency of young children to swallow the small, coin- shaped lithium batteries that power many devices. In the United States, more than 3,500 cases of swallowed batteries are reported to poison control centers each year. And the number of cases involving a fatality increased by 400% between 2005 and 2010.7

Children often put foreign objects in their mouths, and sometimes even swallow them.

But lithium batteries present a particular health concern: Saliva activates an electrical current that can cause severe burns in the esophagus.

This safety issue presented a threat to the battery industry. Left unaddressed, there was a risk of significant numbers of young children being harmed. That, in turn, could lead to public outcry, to regulatory or legislative activity, and to reputational harm to companies that produced the batteries.

Faced with a growing public safety problem, industry leader Energizer developed an issues management campaign, with help from the public relations firm FleishmanHillard, that sought to raise awareness of the safety issue among parents. It also became the first battery maker to voluntarily change its packaging to comply with U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission standards.8

In partnership with Safe Kids Worldwide, FleishmanHillard and Energizer developed “The Battery Controlled” campaign that engaged more than 200 local and community partners. The campaign included education about the risk that coin-shaped batteries pose to young children, helped parents understand how to prevent those batteries coming into children’s reach, and signs to look for that might indicate that a child had swallowed a battery, as well as steps to take immediately if they so suspected.

At the beginning of the initiative, research showed that only 28% of parents of small children were aware of the safety issues. Through traditional and social media and community outreach, the campaign reached more than 220 million people in the first year. And after one year, its research showed that more than 66% of parents of young children were aware of the safety issues.9

For their work, FleishmanHillard and Energizer won a 2013 Silver Anvil—a top award for public relations—in the Issue Management category from the Public Relations Society of America. But more important, they improved public safety in the United States. And by taking the initiative, both to educate parents and to change their packaging to make batteries less likely to get into children’s hands, they avoided significant reputational harm for Energizer and for the entire battery industry.

Case Study 3

In September 2017, the island of Puerto Rico was hit by two Category 5 hurricanes: Hurricane Irma and Hurricane Maria. The hurricanes not only took the lives of thousands of Puerto Ricans, but also devastated the island itself. Images from the seemingly decimated island were broadcast to millions across the world. One of the most iconic images from storm-torn Puerto Rico was the aerial image of “S.O.S. Necesitamos Agua/Comida!!” [S.O.S. We need food/water] drawn in white at an intersection as a signal to passing airplanes.10

In order for the island to recover, Puerto Rico not only needed help to rebuild its infrastructure, but also to revitalize the tourism industry, which represented 6.5% of Puerto Rico’s GDP and approximately 77,000 jobs in tourism-related industries.11 According to the World Travel and Tourism Council, after a natural disaster travelers typically avoid a destination for nearly two years.12 And after the hurricane more than 50% of travelers surveyed said that media coverage of the hurricane had negatively affected their view of Puerto Rico.13 This image needed to change if Puerto Rico was to restore tourism on the island at a faster rate than average.

Work had already been done to revitalize the island’s tourism industry. However, with the one-year anniversary of Hurricane Maria looming, during which the media would predictably re-air the disaster footage that had put travelers off of Puerto Rico, it was vital to convince the media to cover the anniversary not as an island destroyed but rather as a place that has rebounded in a way not seen before.

Discover Puerto Rico, a nonprofit established by the Puerto Rican government, and the PR firm Ketchum partnered to challenge the media to cover the anniversary and tourism on the island in a way that highlighted the resiliency of Puerto Rico and its people. The message of the campaign was #CovertheProgress.

A key component of the campaign was to change the image branded in people’s minds from the hurricane. To do so, they took a new aerial shot of the same intersection that immediately after the storm bore the message “S.O.S.” but instead wrote “Bienvenidos! [Welcome!] #CovertheProgress.” They also created a toolkit with imagery from the island before and after the storm, which included new videos, tourism data, testimonials and photos of members of the tourism industry wielding #CovertheProgress signs.14 The campaign was launched on CNN, the same news outlet that first shared the “S.O.S.” photo, one month before the anniversary. #CovertheProgress was then actively pitched to other news outlets, particularly travel, consumer lifestyle and hard news outlets. Local businesses, travel industry partners and social media influencers were tasked with driving positive coverage of the island, including sharing real-time images of Puerto Rico and “throwback” experiences on the island. Celebrities were also deployed to continue spreading the word that visiting the island was the best way to support Puerto Rico’s recovery efforts. And the CEO of Discover Puerto Rico, Brad Dean, met with New York media in advance of the anniversary.15

The results were astounding. The majority of international media coverage of the anniversary—a full 70%—was positive, with popular themes being “Open for Business” and “facilities being better than ever.” The #CovertheProgress anniversary campaign coverage generated more than one billion earned and social media impressions in a span of four months. Best of all, this positive coverage changed the attitudes of travelers and the travel industry. The travel industry media began recommending the island again as a must-go destination. And in January 2019, just over one year after Puerto Rico was once again “Open for Tourism,” the New York Times named Puerto Rico the number one place to go.16

Ketchum and Discover Puerto Rico received a Silver Anvil award—a top award for public relations given by the Public Relations Society of America—in the Issues Management category. Ketchum and Discover Puerto Rico not only restored and strengthened the tourism industry on the island, but tangibly helped Puerto Rico in its recovery from the hurricanes.

10.3 Developing an Issues Management Plan

The starting point of an issues management plan is an analysis that identifies both the problem to be solved and the organization’s ability to provide meaningful impact on the issue.

The starting point of an issues management plan is an analysis that identifies both the problem to be solved and the organization’s ability to provide meaningful impact on the issue. Effective analysis attempts to develop understanding of the external environment and the organization’s internal state, as well as ways the company might need to adapt operations, practices, procedures or structure. In other words, the analysis is intended to develop both situational awareness and self-awareness.

All too often organizations focus on understanding and trying to manage external issues without acknowledging the internal realities of the company. Issues management then becomes ineffective because the company is constrained throughout the process by internal obstacles such as lack of buy-in or sufficient resources. Over 2,000 years ago, the Chinese philosopher-warrior Sun Tzu identified the need for both situational awareness and self-awareness in navigating through perilous times. He wrote:

This chapter describes an approach to issues management planning that has been field-tested by dozens of companies and organizations from Fortune-25-size giants to small not-for-profit advocacy groups; publicly traded companies and private concerns; and by U.S. corporations and organizations based abroad. It has been applied to issues that threatened a company’s survival and to minor bumps that merely caused embarrassment; to issues that were planned for and expected well in advance, and to those that arose suddenly and became public quickly. The planning process allowed these companies to respond effectively, quickly, and definitively, and to protect their reputations, operations, and financial conditions.

The plan should consist of two key sections:

The plan prescribes the steps to take to protect the company from operational harm and protect or restore the company’s reputation and relations with stakeholders.

- An analysis identifies the issue, event, or potential crisis and assesses the risks: the scope and likelihood of financial, operational, or reputational damage. The analysis section names the problem and elucidates how it is likely to affect the organization and stakeholder groups that matter to the organization.

- The plan prescribes the steps to take to protect the company from operational harm and protect or restore the company’s reputation and relations with stakeholders. Bear in mind that drafting the plan—the proposed solution—without a clear understanding of the problem can be highly counterproductive. It is possible to craft at least an outline of an analysis quickly. An analysis can catalyze an entire management team into a common understanding of the problem and of the ramifications if the issue remains unaddressed.

The issues management analysis and plan may be written in complete sentences or paragraphs, in bullet points, in presentation slide format, or in any other medium that works for the organization in question. The style of the written document is less important than the quality of the thinking and the level of engagement by management in the issues raised in the plan.

10.3.1 “Issue” versus “Event”

Following is a quick summary of the Issues Management Analysis and Planning Template, followed by a detailed description of each element. Note the template is similar to the actions mandated in handling crisis communications. The major difference is that an “issue” is more typically a situation played out over a period of time instead of a singular event.

10.3.2 Introducing the Template

The Issues Management Analysis and Planning Template provides a structured way to think about solutions to a problem.

The Issues Management Analysis and Planning Template provides a structured way to think about solutions to a problem. It provides an ordered, outlined overview of a basic, viable, and strategic issue-management approach. It is a predictable, goal-oriented process that clarifies actions and messages in support of business goals.

Issue Management Analysis and Planning Template

Issue Analysis

- Threat assessment

- Risks

- Magnitude

- Likelihood

- Affected stakeholders

- Additional information for research needed

Issue Management Plan

- Business Objectives

- Issues Management Strategies

- Actions to Take (Tactics)

- Staffing

- Logistics

- Budget

Communication Plan

- Communication Objectives

- Communication Strategies

- Target Audience(s)

- External

- Internal

- Tactics

- Targeted Messages

- Documents

- Logistic

- Success Criteria

10.4 What the Elements of the Issues Management Analysis and Planning Template Mean

10.4.1 Issue Analysis

Issue analysis is descriptive. It answers the question what. It addresses what happened, and what could happen if the issue is not handled properly. It helps to establish both self-awareness and situational awareness.

Issue analysis is descriptive. It answers the question what. It addresses what happened, and what could happen if the issue is not handled properly. It helps to establish both self-awareness and situational awareness.

This establishes the context in which an issue is to be understood and the challenges it presents. It leads management toward a crisis response action plan and communication plan calibrated to the magnitude and likelihood of the event or threat. The analysis is intended to provide management, internal and external staff, and other company employees with a common understanding of the nature of the threat and the possible consequences. The subsequent action plan should be crafted to neutralize damage resulting from the threat identified in the analysis.

The key elements of the analysis are:

The analysis begins by naming the problem: It presents a clear description of the threat and the various ways it could play out.

Threat Assessment: The analysis begins by naming the problem: It presents a clear description of the threat and the various ways it could play out. The threat assessment should avoid euphemism and name the threat clearly.

There are many kinds of threats:

- A negative event within the company, such as termination of key employees, discovery of malfeasance, abrupt departure of key leaders, filing a lawsuit or the verdict in a lawsuit.

- A negative event outside the company but directed at it, such as litigation, a competitor’s triumph, or legislative or regulatory activity.

- A routine business process or decision that risks being misunderstood or will be the subject of opposition.

- An accepted business practice that becomes controversial because the political, social or business environment has changed.

- An event or change in the business environment that affects the company’s competitiveness, financial stability or operations. These could include natural disasters, new legislation, acts of terrorism, or similar issues not directed at the company but from which the company suffers collateral damage.

Risks: In addition to naming the threat, the analysis should address why the threat is something to be managed.

- What is the likely impact on the organization? On its financial condition, financial and, operational health, its relationships with stakeholders?

- What is the likelihood that the issue, left unmanaged, will cause harm?

- What is the likelihood the company can minimize or prevent that harm?

- What is the likelihood the company will make matters worse?

10.4.2 Sample Threat Assessment: An Embezzlement

The threat assessment should assess the specific business processes, business relationships and elements of the business environment that might be affected. For example, a company discovering employee embezzlement might identify the following as areas of concerns. Reasons existing control structures did not detect the embezzlement earlier:

- Facilitation by or participation of other employees

- Vulnerability of other areas (financial reporting, physical property theft, accuracy of pre-employment data, etc.)

- History of similar events

- Advisability of involving law enforcement

- The need to dismiss the employee; and what to say internally upon the employee’s dismissal

- Desirability of investigating via internal or external legal and accounting resources

- Likelihood of news of the embezzlement leaking

- Advisability of proactive disclosure of discovery and steps taken to identify scope and prevent recurrence

- Materiality of the dollar amount and the need to disclose into the financial markets

- Connections between the embezzlement and seemingly unrelated problems that might become public in the same timeframe

- The probability that competitors, adversaries, activists, regulators, or others may use the event to agitate against or embarrass the company

In addition to the business processes, relationships, and environmental challenges, the threat assessment should also identify the likely visibility that the threat represents, either left to itself or if mishandled, including visibility in the news media and likely public comment by investors, adversaries, regulators, legislators, ratings agencies, securities analysts, employees, and others.

To the degree that the issue is caused or may be inflamed by an adversary, the threat assessment should also anticipate the adversary’s likely plan of attack and its next moves.

10.4.3 Alternative Scenarios

It may also be useful for the threat assessment to include a number of possible scenarios, particularly when the threat is outside the control of the company.

It may also be useful for the threat assessment to include a number of possible scenarios, particularly when the threat is outside the control of the company. For example, if a regulatory investigation is underway, there may be several scenarios including:

- The investigation concludes that there was no malfeasance on the part of the company or its officers.

- The investigation concludes that there was malfeasance on the part of a single or limited number of employees of the company.

- The investigation concludes that malfeasance was widespread and endemic within the company.

Similarly, in the case of a pending verdict in litigation, the scenarios could include:

- The company has a major victory.

- The company has a major defeat.

- An ambiguous verdict that finds for us in some elements of the case, but against us in others.

- The company settles on favorable terms that are publicly disclosable.

- The company settles on confidential terms.

For each scenario, there would be a corresponding list of considerations, including an assessment of the likely response to each outcome among those who matter to the company, and the company’s and adversary’s likely next steps (appeal, settlement discussion, initiation of new litigation, etc.)

10.4.4 Magnitude Analysis

The magnitude analysis assesses the threat’s relative impact on the company’s reputation and operations.

The magnitude analysis assesses the threat’s relative impact on the company’s reputation and operations. If the threat could play out according to several scenarios, the reputational and operational impact of each scenario should be assessed. This assessment involves the same process as was described earlier, in the discussion of prioritizing various issues.

10.4.5 Likelihood Analysis

The likelihood analysis assesses the relative.

The likelihood analysis assesses the relative certainty or probability that any particular event will take place and will cause operational or reputational damage. As with the magnitude analysis, the likelihood analysis should take account of different scenarios.

Probability that any particular event will take place and will cause operational or reputational damage.

The likelihood/magnitude matrix described earlier in this chapter should be used to plot the relative impact of an issue or set of scenarios.

10.4.6 Affected Stakeholders

The stakeholder analysis creates an inventory of the groups likely to be most affected by the issue and their likely attitudinal or behavioral predispositions. These stakeholders could include internal groups such as employees, specific internal functions or departments, or affiliated groups who function as internal resources, such as contractors, brokers, or an independent sales force; or external groups such as regulators, customers, investors, allies or adversaries.

For each stakeholder group named, the analysis should inventory what is known about the group and how it is likely to interpret the issue in question:

- Which people and groups matter in this situation?

- Which will influence, be influenced by, or form expectations about the outcome of this issue or event?

- What do we know about them?

- What else do we need to know about them?

- What would reasonable members of those groups appropriately expect a responsible organization to do in such a situation? (See Chapter 11 for more on this concept.)

10.4.7 What Additional Information or Research Is Required?

The analysis should also identify additional specific information that needs to be obtained in order to either fully assess the threat or to begin the planning process. It also identifies the internal and external resource persons who need to be consulted or involved in the planning process.

10.5 The Issue Management Plan

Whereas the issue analysis was descriptive, the issue management plan is prescriptive: It prescribes a course of action to deal with the situation as presented in the analysis.

Once the issue or event has been analyzed, the issue management plan can be constructed. Whereas the issue analysis was descriptive, the issue management plan is prescriptive: It prescribes a course of action to deal with the situation as presented in the analysis. Not all of the following categories may apply in every case. However, each category should be considered for each issue, event, or crisis, and the decision not to include one or more categories in any particular written plan should be made based on the issue in question.

At the very least, every plan should include business objectives, issues management strategies, actions to take, communication objectives, communication strategies, messages and tactics.

At the very least, every plan should include business objectives, issues management strategies, actions to take, communication objectives, communication strategies, messages and tactics.

10.5.1 Business Objectives

Business objectives.

Business objectives describe what will be or what ought to be done if the company’s management of the issue is effective.

Define the business goals that the actions and communications will accomplish.

These objectives define the business goals that the actions and communications will accomplish. They are formulated as desired outcomes: the resulting status or change in the business environment that action and communication is intended to create. Typically, the business objective is the mitigation or prevention of the major risks identified in the issue analysis.

For example, for each of the following risks, the business goals could include:

- If the risk is loss of market share, the goal would be to maintain market share despite a product recall or pricing pressures.

- If the risk is adverse action by regulators, the goal would be to prevent regulators from taking action against the company in the wake of discovering problems.

- If the risk is legislative action that would restrict a company’s activity, the goal would be to prevent legislation from being introduced that would restrict a company’s ability to operate in its marketplace profitably.

- If the risk is the loss of workforce productivity, the goal would be to sustain productivity during a management shakeup.

- If the risk is that investors would stop investing in the company, the goal would be to preserve the ability to raise capital in the wake of a financial scandal.

- If the risk is that the company could go bankrupt, the goal would be to avoid involuntary bankruptcy.

10.5.2 Issue Management Strategies

The issue management strategies describe how the business objectives will be achieved.

The issue management strategies describe how the business objectives will be achieved. They delineate the conceptual frameworks that a company will use to organize its energies and deploy its resources to influence the business environment, and protect the company’s operations and reputation, and to remedy any damage. They further describe ways the problems identified in the analysis will be fixed.

Strategies are not actions to take. It is easy to confuse the two.

Strategies are not actions to take. It is easy to confuse the two, and the difference between strategies and actions to take (tactics) is described in greater detail next. In general terms, though, strategies will be the constant processes to be employed using many changing tactics.

10.5.3 Actions to Take (Tactics)

Actions to Take describes the specific business decisions that need to be made or steps that need to be taken. These are the tactics to implement in order to reduce vulnerabilities, mitigate harm, or to restore trust or confidence quickly. The actions could be changes to an operating process, convening of a team of people designated to handle the company’s response to a crisis, articulation of steps to take to reach various stakeholder groups or any other concrete step. For the plan to work well, the actions to take should each put into operation at least one of the issue management strategies. An action that does not derive from one of the issue management strategies is likely to be counterproductive in at least three ways: First, it may not help solve the problem and could even make it worse; second, it expends resources that could otherwise be directed to solving the problem; and third, the misguided action makes management believe that it is taking effective steps to solve the problem.

The Actions to Take section could also include a menu of possible actions to be considered under various scenarios, as well as timelines of events known or expected to take place in the future, or targets for certain company-initiated activities to take place. The timetable may also prescribe regularly scheduled meetings or conference calls for the core team, its advisers, and management to review progress and facilitate decision-making.

10.5.4 Secure Area

A company may consider establishing a secure room or suite of rooms (known informally as a “war room” or “operations center”).

Depending on the scope and duration of an issue, a company may consider establishing a secure room or suite of rooms (known informally as a “war room” or “operations center”) to serve as a location for the issues management team to work. Such a facility usually has restricted access and robust technological capability including phone lines, conference call capability, secure computers, printers, fax, and copiers, plus cable television, presentation slide projection capability, and a shredder. Much of the work product generated by the team can be produced in the room, and meetings of the core team can take place there, which will reduce distraction and curiosity in normal operating areas of the company and diminish the flow of rumors.

10.6 The Difference between Issue Management Strategies and Tactics (Actions to Take)

It is easy but counterproductive to confuse strategies and tactics. The two must be kept clear and distinct. The tactics serve the strategies, which in turn serve the business objectives.

Issue management strategies describe in conceptual terms how the objectives will be accomplished. The strategies are unlikely to change as the crisis unfolds. But the actions to take—the tactics—are likely to change. Multiple actions can support a single strategy. And as the circumstances evolve, some actions may be discontinued and others begun, all in the service of a single strategy.

For example, a strategy could be: Identify the scope and severity of an embezzlement.

For that single strategy there could be a number of actions to consider. These could include:

- Retain a forensic accountant to review the books and determine whether other funds were stolen, as well as how the embezzlement took place

- Retain an outside law firm to conduct a thorough investigation

- Review whether there were any other instances of dishonesty by the employee, including expense reports, prior employment and educational data, vendor relationships, and the like

- Cooperate with law enforcement authorities investigating the criminal elements of the embezzlement

These actions are not mutually exclusive, but all or part could be conducted simultaneously or in sequence. New tactics may arise as the issue unfolds, as the company learns more about the embezzlement, and as the stakeholders who matter to the company react to the issue and to the company’s initial responses. All proposed tactics should be compared to the strategies to determine whether each possible tactic serves an existing strategy. No tactic should be embraced unless it demonstrably supports at least one strategy. And the totality of tactics needs to demonstrably support the totality of the strategies. If there is a strategy that is not supported by at least one tactic, the tactics list is not sufficiently developed.

If it becomes difficult to differentiate between strategies and tactics, a simple rule of thumb could help: Strategies are conceptual; tactics are tangible. You can assign a precise cost or date for the tactics, whereas the strategies transcend such tangible precision. In the earlier embezzlement example, the strategy is to identify the scope and severity of an embezzlement. However tempting, it is difficult to assign a particular cost or date to that strategy. The tactics, on the other hand, are more concrete. The first tactic is to retain a forensic accountant to review the books.

This is tangible. You can point to a particular accountant to be hired for a particular fee to deliver a report on a particular date. The other tactics are similarly concrete, and each could be quantified if necessary.

10.6.1 Staffing

The issues management plan should designate the team or teams who will work on issues day to day. Most plans identify a core team that is accountable for results. That team is often empowered to prepare the plan for management review and approval, and to implement the plan once approved.

Some plans identify both the core team and a governing group of managers to whom the core team will report and who can quickly facilitate the allocation of resources.

The plan should also identify other resources, both internal and external, that the team can draw upon or who may be asked to join the core team. These can include legal counsel, accounting or investment banking counsel, crisis communication counsel, operations, security, human resources, and other functional experts who can contribute based on the company’s needs and the specifics of the issue.

Part of organizing the core team is developing a complete and up-to-date working group list of all the people involved in the issue. This should include names; titles; assistants’ names; and all relevant addresses, phone, mobile phone, email, pager and other contact information.

The staffing section of the plan may also describe the frequency of core team or management team meetings, conference calls, and other contact, as well as an expedited process for review and approval of documents.

10.6.2 Logistics

The logistics section of the plan, which is optional, identifies the operational details that need to be addressed for the plan to work. The logistics section covers everything from who will be responsible for what work product; to the number of desks, printers, photocopiers, phone lines, etc. that will be required for the secure war room; to ensuring access to the building after hours; to making certain that teams working late are fed and have transportation home at night or a place to sleep.

The logistics section of the plan can range from a single piece of paper to a large three-ring binder to a computerized database. This helps the core team or its leaders understand how to operationalize the tactics they recommend and the day-to-day procedures of the crisis team.

10.6.3 Budget

The budget section is also optional and addresses the costs of managing the crisis, including the retention of outside experts, out-of-pocket expenses, and remediation of the underlying crisis, including possible costs of litigation, medical care, reconstruction of facilities, etc.

Very often cost is the least important consideration in managing an issue. But it is useful to have some accountability and predictability in cost; at the very least to have a mechanism to ensure that resources are properly allocated and to understand the consequences of assigning additional resources to a crisis. But in general terms, responses are not driven by a budget, and certainly should not be held up while a budget is being developed and approved.

10.6.4 Communication Planning

Because most issues are or could become public, and because much damage to an organization’s operations and reputation are based on public reaction and criticism of the company, each issue management plan should include a communication section.

Because most issues are or could become public, and because much damage to an organization’s operations and reputation are based on public reaction and criticism of the company, each issue management plan should include a communication section.

The communication section is intended to support the business strategies and actions to take. It should be written following the establishment of the business strategies and specification of the actions to take. Because speed is sometimes a factor in issues management, it may not be necessary to wait until the logistics and budget sections are fully completed before beginning communication planning. Ideally, the communications plan should be written as an integral part of the issues management plan.

10.6.5 Communication Objectives

Communication objectives answer the “conceptual what” questions. What will be the end result of our communications efforts, effectively implemented? Objectives describe desired outcomes, not the processes by which these outcomes will be accomplished. Communication objectives answer these questions:

- What do we want those who matter to us to think, feel, know and do?

- What are the changes we seek in what they think, what they feel, what they know and what they do?

Communication objectives describe the attitudes, emotions or behaviors to be exhibited by your stakeholders.

Whereas business objectives describe the desired change in the business environment, communication objectives describe the attitudes, emotions or behaviors to be exhibited by your stakeholders as result of your communication program. Communications objectives could include:

- Changes in knowledge, awareness, understanding, support or feelings

- Steps we expect our audiences to take, such as approving a course of action, supporting a point of view or trying a new product

- Neutralizing or minimizing the impact of negative visibility on audiences’ thinking

For example, if a business objective is to maintain the company’s stock price, the communication objective may be to maintain investor confidence in the company’s management team and prospects for future success.

10.6.6 Communication Strategies

Communication strategies are ways in which the communication goals will be achieved. Communication strategies answer the “conceptual how” questions. In broad overview, how will the communication objectives be accomplished? Once we know what we want our stakeholders to think, feel, know and do, the communication strategies answer these questions:

- How do we get them to think, feel, know and do those things?

- What are the ways we can organize our audience engagements to get them to think, feel, know and do those things?

As with business strategies and actions to take, it is common to confuse communication strategies, which answer “conceptual how” questions, with communication tactics, which answer “operational how” questions. The difference between business strategies, communication strategies, and communication tactics is critical.

The communication strategies provide the broad game plan for all communication activities.

The communication strategies provide conceptual frameworks for accomplishing the communications objectives. They provide the broad game plan for all communication activities. For example:

- A business objective could be: Maintain the company’s stock price.

- A communication objective to support the business objective may be: Maintain investor confidence in the company’s management team and prospects for future success.

- A communication strategy to support that communication objective may be: Keep analysts and investors aware of progress being made to solve problems.

- Among the many communication tactics to support that communication strategy could be:

- Send an email to all analysts with an update

- Hold a conference call with analysts and investors

- Post regular updates on the website

- Be prepared to field inquiries from analysts and investors

- Conduct an interview with a financial newspaper that is read by investors

10.6.7 Audiences

The audiences section lists the stakeholders to whom the communications will be directed.

The audiences section lists the stakeholders to whom the communications will be directed. While not every communication plan needs an audience section, it provides a reality check in the form of an inventory of the groups who matter and to whom communications will be directed.

The audience inventory, in turn, informs the balance of the plan. In general, the tactics section ought to include at least one mechanism for reaching each audience, either directly or indirectly.

It is common for audiences to be prioritized in a number of ways. A typical prioritization order is:

- Internal: board of directors; all employees; departmental, regional, or specific-level employees; senior management; etc.

- External: current shareholders, the market as a whole, governments, academics, activists, etc.

It’s also common to differentiate ultimate audiences, those you ultimately want to reach and who matter directly to the success of the organization, and indirect or influencer audiences, who are not necessarily your stakeholders but through whom you reach your stakeholders.

Examples include:

- Ultimate audiences: employees, shareholders, regulators, the general public

- Influencer audiences: media, investment analysts, academics, consumer advocates, etc.

10.7 Ultimate Audience/Influencer Audience

A stakeholder that in some circumstances is an ultimate audience can be an influencer audience in other circumstances. For example, if we are seeking initial analyst coverage of our stock, analysts are an ultimate audience. However, if we wish to persuade shareholders to accept a point of view, we may consider the analyst to be an intermediary audience, to whom we communicate in order for the analyst to then communicate our message to shareholders.

The list of audiences in the plan may or may not be identical to the list of affected stakeholders in the analysis portion of the template. The difference is the following: For purposes of analysis it is useful to identify those stakeholders who are affected by the issue in question. However, not every affected stakeholder group would necessarily be an audience of communication. Similarly, some audiences (e.g., the media) may not be an affected stakeholder group, but may be instrumental in reaching an affected stakeholder group (such as customers) to whom direct communication will not be attempted.

10.7.1 Messages

Messages are the critical thoughts we wish the audiences to internalize; the core themes we wish to reinforce in all communications.

Messages are the critical thoughts we wish the audiences to internalize; the core themes we wish to reinforce in all communications.

The word “message” has many possible meanings, but for the purposes of developing an issues management plan, it should be understood to mean what you want those stakeholders who matter to the company to think, feel, know or do—and what you need to say in order for those groups to think, feel, know and do those things. As a general rule, the messages can be determined by focusing on the communications objectives: The desired attitudinal, emotional or behavioral outcomes among ultimate audiences.

One way to determine the messages is to undertake the following process:

- 1. Assume your ultimate audiences. What do you want them to know, think or feel about either the company or the issue in question? What is the strongest credible thing you can say that, if believed, will cause them to know, think or feel this way? This becomes your first message.

- 2. Assume that your audience has fully internalized the first message. What is the second thing you want them to know, think or feel about either the company or the issue in question? This becomes your second message.

- 3. Assume that your audience has fully internalized the first two messages. What is the third thing you want them to know, think or feel about either the company or the issue in question? This becomes your third message. As a general principle, three messages are the maximum you can expect any audience to internalize.

These three sentences become the three topic sentences that drive all substantive communication about the issue. Just as tactics may change but strategies usually will not, the factual support to a particular message may change as the crisis unfolds, but the message usually will not. And different support statements may be used with different audiences, or with the same audience at different times, while the message remains unchanged.

10.7.2 Using Core Messages

The three core messages stand by themselves, and should be included in each communication the company makes regarding the issue: These three messages become the quote in the press release; they become the topic sentence in employee meetings; they become the outline of presentations to the investment community; they become the three themes in letters to regulators or to customers; they serve as hyperlinks on the company’s website, driving a visitor deeper into the supporting detail of each. The three messages need to be repeated every time the company communicates about the issue, requiring a very high tolerance for repetition.

The ability to consistently articulate the top three things a company wants its stakeholders to know is a critical attribute of leadership and essential to effective management of issues.

It is only at this point in the planning process that attention should turn to the tactics.

Paradoxically, most companies reflexively default to tactics as a first resort.

This is the rookie’s mistake in issues management and crisis avoidance.

Paradoxically, most companies reflexively default to tactics as a first resort: “We need to hold a press conference” or “We need to send out a press release.” This is the rookie’s mistake in issues management and crisis avoidance. It is impulsive, unthoughtful activity, and it is often both self-indulgent and self-destructive. But once the plan is in place, a framework for using the tactics effectively can be established, and the implementation of the plan can be accomplished in a flexible, effective and cost-effective way.

10.7.3 Communication Tactics

Communication tactics are the specific communications techniques that will be employed to convey the messages to the ultimate audiences. The tactics part of the plan is a substantive inventory of the communications activities to be undertaken. It is what will actually be done to send the messages. As a result, it tends to get the most attention.

Because communication tactics involve what people actually do, they may tend to drive the communications planning process. It is easy for people to focus on interesting tactics (“let’s hold a press conference,” “let’s do a Facebook page,” “let’s launch a Twitter campaign”) regardless of the purpose or whether sufficient resources are available for effective execution.

Choice of tactics should be driven by two general considerations, each of which requires a degree of discipline.

- First, communication tactics should be driven by the communication strategies: The tactics should not be determined until after there is a clear articulation of the analysis, the business objectives and strategies, and the communication objectives and strategies. There should be at least one strategy that demonstrably accomplishes each objective. And each tactic should demonstrably support at least one strategy.

- Second, tactics should be doable. Napoleon once remarked, “Amateurs worry about tactics, professionals worry about logistics.” What is sustainable should govern tactics. The plan should not, for example, include labor-intensive tactics unless it also addresses staffing and other resources. And it shouldn’t promote “gee-whiz” technologies unless it also addresses how those technologies will be obtained and delivered.

There should be specific communication tactics listed to support each strategy (and, as appropriate, each audience).

Communication tactics are deliverable items. They may include:

- Employee memoranda or emails

- Press releases

- Website postings, social media posts

- Press conferences

- Op-ed articles in newspapers

- Advertisements

- Investment community conference calls

Because each tactic is subordinate to a specific strategy to achieve a known objective, it becomes easy to discard tactics that aren’t working and replace them with new tactics that are more likely to work.

One virtue of the systematic planning process that this template represents is that it allows for prompt midcourse correction without losing sight of objectives. If the objectives, strategies, audiences and messages are clear, it is easy to adapt the plan to ensure it is accomplishing its purpose.

10.7.4 Documents

The documents section of the plan is optional. It is intended to serve as an inventory of specific pieces of writing necessary to execute the communication tactics.

The document section identifies each individual communication required to implement the tactics. Since each piece of communication needs to be drafted, and since all need to be consistent and mutually reinforcing, this section constitutes a work list of documents to be produced before tactics can be executed.

These documents will include:

- Press releases

- Media Q&A

- Employee emails

- Employee Q&A

- Call-center scripts

- Call center Q&A

Note three different Q&A documents are called out. Since each is a Q&A format, a document inventory makes it clear that a separate Q&A is needed for three separate audiences. The three Q&A’s will provide different emphases and different levels of detail, but all three will be consistent with and mutually supportive of each other.

10.7.5 Communication Logistics

The communication logistics section identifies the resources and tools necessary to implement strategies and execute tactics. Like the documents section, it is optional. Like the documents section, it serves as a kind of reality check against tactics. It may include timeline of preparation and execution of tactics. It may also include the resources necessary to prepare the tactics for execution, or the individuals tasked to draft documents, seek approvals, or perform other tasks.

10.8 Best Practices

- Focus on the goal, not just on the processes

- Get management buy-in

- Name an accountable leader

- Involve all relevant business functions

- Set tangible communication objectives and measure success against them

- Follow the plan, focusing on the goal; adapt the tactics to changes in the environment, but keep the emphasis on the goal

10.9 Questions for Further Discussion

- 1. Why is it so important to get management buy-in for an issues management process?

- 2. What is the optimal relationship between the issues management process and media relations and employee communications?

- 3. How can an effective plan make issues management more effective?

- 4. What is the difference between ultimate audiences and intermediate audiences?

- 5. Why is message discipline so important in issues management?

10.10 Resources for Further Study

Issue Action Publications, affiliated with the Issues Management Council, publishes a range of resources for those with issues management responsibility. It publishes two monthly newsletters:

- Corporate Public Issues and Their Management

- The Issues Barometer

It also publishes a range of issues management books. It can be found at www.issueactionpublications.com.

The Issue Management Council is a professional membership organization for people whose job includes issues management. It offers conferences, publications and other resources. It can be found at www.issuemanagement.org.