2

The Financial Consequences of Alternative Restructuring Strategies

16

Employment downsizing is not the only way to restructure, although it certainly is a popular strategy. Managers often assume that it will lead to improvements in financial performance. The research presented here tests that assumption.

Are companies better off financially after restructuring? To address this question, two colleagues (one from finance, one from marketing) and I studied financial and employment data from companies in the Standard & Poor’s 500 (the S&P 500) from 1982 to 1994. The S&P 500 is one of the most widely used benchmarks of the performance of U.S. equities. It represents leading companies in leading industries, and consists of 500 stocks chosen for their market size, liquidity, and industry group representation. Each stock’s weight in the index is proportionate to its market value (stock price times number of shares outstanding). However, the stocks that comprise the index do not remain constant over time. In fact, from its inception in 1926 through September 15, 2000, 1,001 companies exited the S&P 500, the overwhelming majority as a result of mergers and acquisitions.1

Our purpose was to examine the relationships between changes in employment and long-term financial performance. Specifically, we measured changes in profitability (return on assets, or ROA) and the total return on common stock (dividends plus price appreciation). We categorized companies based on their level of change in employment and their level of change in plant and equipment (assets), and we observed performance from one year before to two years after the employment-change events.217

Our primary interest was the change in employment from one year to the next. Over the period of the study, however, some companies increased their levels of employment, others decreased their levels of employment, and many did both at various times. Moreover, some changed their employment through hiring and/or layoffs, while others reported employment changes that must have resulted from purchasing or selling plants or divisions. For example, suppose a firm reports a 10 percent reduction in employment from 1990 to 1991. That reduction in employment could be due to a decision to lay off employees without any reduction in assets, or it might be due to a decision to sell off unprofitable plants or divisions. The former set of circumstances represents a pure employment downsizing, while the latter represents a downsizing with divestiture. Each of these scenarios might have a different impact on a firm’s financial performance. For example, the market might react differently over time to a divestiture than it does to an employment downsizing. By considering changes in employment relative to changes in assets, we were able to account for most of the effects of changes in each of them.

To control for the varying impacts of employment increases or decreases, and for changes due to variability in employment per se, versus asset acquisitions or divestitures, we classified each firm into one of seven mutually exclusive categories in each period of the study:

- Employment Downsizers: companies in which the decline in employment is greater than 5 percent and the decline in plant and equipment is less than 5 percent

- Downsizing by reducing assets (Asset Downsizers): companies with a decline in employment greater than 5 percent and a decline in plant and equipment that exceeds the change in employment by at least 5 percent

- Combination employment and asset reduction (Combination Downsizers): companies that reduce the number of employees by more than 5 percent but do not fit into either of the two prior categories

- Stable Employers: companies with changes in employment between plus or minus 5 percent

Although our focus was on downsizing, we also categorized companies based on their employment growth. To do that, we defined three more categories relating to employment upsizing:18

- Employment Upsizers: companies in which the increase in employment is greater than 5 percent and the increase in plant and equipment is less than 5 percent

- Upsizing by acquiring assets (Asset Upsizers): companies with an increase in employment of 5 percent or greater and an increase in plant and equipment that exceeds the change in employment by at least 5 percent

- Combination employment and asset increase (Combination Upsizers): companies that increase employment by more than 5 percent but do not fit into either of the other upsizing categories

We recognize that our classification of companies as Down-sizers, Upsizers, or Stable Employers is somewhat arbitrary. For stable employers, we chose ±5 percent, relative to a base year, as a cutoff point. We considered 3 percent and 10 percent as alternative limits, but we concluded that using ±3 percent would include in the employment downsizing categories too many companies that could have reduced their employment that much merely through attrition and not through a conscious downsizing decision. On the other hand, using ±10 percent excluded from the downsizing categories many larger companies that had announced and implemented employment downsizings that were quite large in terms of the absolute numbers of employees affected.

RESULTS OF THE 1982-1994 STUDY

Impact on Financial Performance

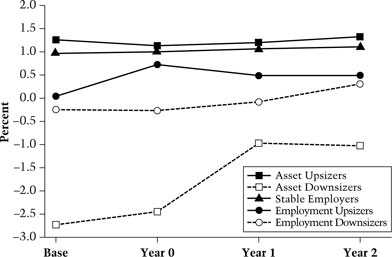

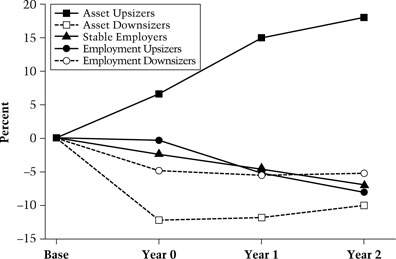

We found no significant, consistent evidence that employment downsizing led to improved financial performance, as measured by return on assets (ROA) and industry-adjusted ROA.a It is important to assess results relative to results for the same industry in which a firm competes, because firms in the same industry face similar economic and competitive conditions. We found that on average, Employment Downsizers were less profitable in the year of the downsizing (the base year) than either the Upsizers or Stable Employers. They remained that way for the subsequent two years. It was only by the end of year 2 that the ROA of Employment Downsizers was slightly higher than that of their industry, but it still fell below that of Stable Employers. Only Asset Downsizers showed a significant increase in their profitability relative to Stable Employers and their industries by the end of year 2. These results are shown graphically in Exhibit 2.319

EXHIBIT 2 Industry-Adjusted Return on Assets for Downsizing Companies

Thus, performance improvement appears to depend on the reason for the downsizing. The firms that engaged in aggressive asset restructuring improved their profitability and outperformed their industries, while those that did not tended to experience declines in their profitability and did not outperform their industries. This suggests that simply laying off employees to improve financial performance may not lead to the intended improvement in a firm’s financial performance if the layoffs are not accompanied by thoughtful restructuring of the firm’s assets.

A striking feature of our findings was that employment downsizing had a negligible impact on profitability when compared to the size of the layoffs. Employment Downsizers reduced their workforces by an average of 10.5 percent, but they failed to increase their profitability (ROA) until the end of year 2. Even then, they were able to attain an ROA that was only 0.3 percent above their industry average, which is not significant, considering the high percentage of layoffs. No matter how many employees they lay off, employers that downsize always seem to trail the performance of Stable Employers. Nevertheless, companies continue to announce large layoffs, assuming that employment downsizing will increase profits.20

Impact on Stock Performance

The second measure of performance used in the study was the total return on common stock. We tracked the stock return for companies in each of the seven categories from one year prior to the employment changes through the second year after the employment changes. We then compared the returns to the Stable Employers and to each company’s industry. The results were very clear. In the year that they increased employment, the three categories of Upsizers generated stock returns that were 50 percent higher than the Stable Employers (0.27 vs. 0.18) did. Over the three-year period, upsizing companies as a group generated cumulative stock returns that were 20 percentage points higher than the Stable Employers did. On the other hand, the downsizing companies as a group performed no better than the Stable Employers over the same three-year period.

We adjusted each company’s stock return for industry performance by subtracting the average industry stock return from the company’s return. The resulting industry-adjusted return implicitly takes account of risk because the industry-average return will, itself, include a risk premium for the systematic risk of that particular industry. Thus, any return that is significantly different from that of the industry is a return that is in excess of the return required for that industry’s level of risk. As it turned out, none of the categories exhibited returns that were significantly different from those of their industries.

EXTENSION AND UPDATE FROM 1995 TO 2000

21

To date, scholars have not found consistent relationships between downsizing and financial performance,4 but they have used different analytical approaches, and generally have not examined performance over multiyear periods. However, one exception is research reported in the 2001 book Good to Great, which identified companies that sustained superior financial performance for 15 or more years. Good-to-great companies generally avoided layoffs:

The good-to-great companies rarely used head-count lopping as a tactic and almost never used it as a primary strategy.… Six of the eleven good-to-great companies recorded zero layoffs from ten years before the breakthrough date all the way through 1998, and four others reported only one or two layoffs.

In contrast, we found layoffs used five times more frequently in the comparison companies than in the good-to-great companies. Some of the comparison companies had an almost chronic addiction to layoffs and restructurings.

It would be a mistake—a tragic mistake, indeed—to think that the way you ignite a transition from good to great is by wantonly swinging the ax on vast numbers of hardworking people. Endless restructuring and mindless hacking were never part of the good-to-great model.5

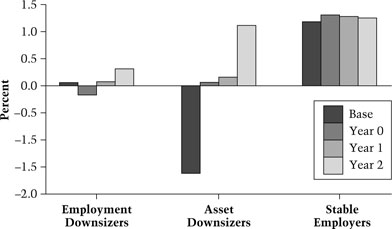

In an effort to provide a large-sample estimate of the relationship between downsizing and financial performance, my colleague Clifford Young and I updated our earlier analysis to include results through the end of 2000.6 Using the same approach as in the previous study, we observed a total of 6,418 occurrences of changes in employment for S&P 500 companies over the 18-year period from 1982 through 2000. Exhibit 3 shows the distribution of cases across the various employment-change categories from the year of the announcement (year 0) through years 1 and 2. Exhibit 4 shows the industry-adjusted return on assets across upsizing and downsizing categories, relative to that of Stable Employers, from the year prior to the announcement (the base year) through the year of the announcement (year 0) and the subsequent two years. Note that for the sake of clarity, Exhibit 4 does not include results for the Combination Downsizers and Upsizers.

EXHIBIT 3 Change in Employment 1982-2000 (percent) by Employment-Change Category 22

As in our earlier study, notice how Downsizers, either Employment Downsizers or Asset Downsizers, never outperform Stable Employers in terms of industry-adjusted profitability (ROA).

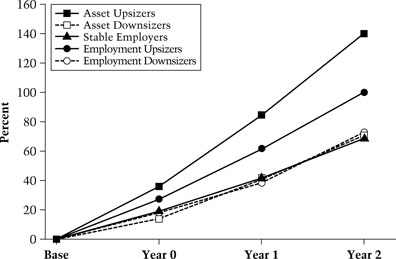

STOCK RETURN

The final judgment as to the effectiveness of a management action is whether it can generate stock returns that are attractive to investors. Exhibit 5 shows the cumulative, industry-adjusted return from investing in a portfolio of companies in each category, starting at the

EXHIBIT 5 Return on Common Stock, Cumulative from Beginning of Event Year, 1982-2000

beginning of the year of the employment/asset change and continuing on through the following two years. These data represent the time period from 1982 through 2000.24

What is the total compound return that an investor would have earned by the end of year 2 from an investment at the start of year 0 in a portfolio of companies in each category that earned the annual returns shown for years 0, 1, and 2? For each $1.00 invested, the investor would have the following by the end of year 2:

Exhibit 6 shows that the Asset Upsizers generated cumulative stock returns that were significantly higher than those of their industries—an average of 18 cents higher by the end of year 2. No other employment/asset change category would have generated returns that were significantly higher than those of their industries.

These results suggest that downsizing strategies, either employment downsizing or asset downsizing, do not yield long-term payoffs that are significantly larger than those generated by Stable Employers. The latter group includes those companies in which the complement of employees did not fluctuate by more than ±5 percent. This conclusion differs from that in our earlier analysis of the data from 1982 to 1994.7 In that study, we concluded that some types of downsizing—namely, asset downsizing—do yield higher ROAs than either Stable Employers or their industries. However, when the data from 1995-2000 are added to the original 1982-1994 data, a different picture emerges. That picture suggests clearly that, at least during the time period of our study, it was not possible for firms to “save” or “shrink” their way to prosperity. Rather, it was only by growing their businesses (asset upsizing) that firms outperformed Stable Employers as well as their own industries in terms of profitability and total returns on common stock.

In pondering these results, it is important to keep in mind two limitations of the study. First, we were not able to adjust statistically for the state of each organization’s financial health or for its industry’s economic conditions prior to the changes in employment or assets. That is, while we did not look at what caused the change, declining sales or profitability are factored into our results because we considered the change in profitability from year 0 to year 1 to year 2. Industry-adjusted returns also take into account the fact that all firms in an industry face the same set of economic conditions.25

EXHIBIT 6 Industry-Adjusted Return on Common Stock, Cumulative from Beginning of Event Year, 1982-2000

Second, we only looked at the specific reduction of expenses due to people. Surely a company facing declining sales must reduce expenses in order to avoid an even greater decline in profits. We did not look at other possible avenues of expense reduction. What our results show, however, is that reducing labor costs per se does not necessarily return a company to profitability.

Is It Always a Mistake to Downsize Employees?

Our results do not suggest that firms should not reduce the size of their workforces under any circumstances. In fact, many firms have downsized and restructured successfully to improve their productivity. General Electric under Jack Welch is a prime example.8 In the aggregate, the productivity and competitiveness of businesses in many different industries have increased in recent years. However, the lesson from our analysis is that firms cannot simply assume that layoffs are a quick fix that will necessarily lead to productivity improvements and increased financial performance. Increasing the likelihood that employment downsizings will result in the desired improvements requires a careful analysis of the expected consequences on all of a firm’s stakeholders, including customers and local communities.26

Managers of publicly owned firms have an obligation to run them as efficiently as possible. Even if these firms are large and stable, managers should be searching for ways to improve their firms’ profitability, including adjusting their workforces. Yet, what is striking about the results of the employment downsizings is the negligible impact on firm profitability relative to the size of the layoffs. The Employment Downsizers reduced their work forces by an average of 10.87 percent in the year of the announcement and 5.66 percent by the end of year 2. While they did increase their returns on assets (ROAs) slightly (0.5 percent), their profitability never exceeded that of Stable Employers that did not downsize. Relative to their industries, they were able to attain a ROA that was only 0.3 percent above their industry average by the end of year 2. The Combination Downsizers reduced their workforces even more—20.3 percent in the year of the announcement and 15.71 percent by the end of year 2—yet showed profitability results that were little better than those of the Employment Downsizers.

What are the implications of this study? Senior managers are under considerable pressure from their stockholders to improve financial performance. Often they try to do this by cutting costs or restructuring assets. Many managers have accepted employment downsizing as a strategy for cutting costs in a manner that is tangible and predictable. Does such cost cutting translate into higher profits? Our research, done at the firm level rather than at the level of the strategic business unit, has not produced evidence that downsizing firms were able generally and significantly to improve profits or cumulative returns on common stock. On the other hand, the evidence indicates that upsizing firms were able to please their stockholders, and Asset Upsizers generated stock returns that were superior to those of their industries in every year after the base year.

Given these results, we conclude that employment downsizing may not generate the benefits sought by management. Managers must be very cautious in implementing a strategy that can impose such traumatic costs on employees, both on those who leave as well as on those who stay.9 Management needs to be sure about the sources of future savings and carefully weigh those against all of the costs, including the increased costs associated with subsequent employment expansions, when economic conditions improve.27

EMPLOYMENT DOWNSIZING AND FLEXIBILITY

This study did not directly address the issue of flexibility. However, many firms may have increased their strategic flexibility by thoughtful downsizing and asset restructuring. Certainly they sharpened the focus of their businesses by divesting business units that did not fit with their missions. Others eliminated excess employees and cut costs to improve their competitiveness.

However, there is a paradox in the attempt to make a company “lean and mean,” while maintaining the flexibility to “turn on a dime.” To turn on a dime, a company must have the flexibility to take advantage of emerging prospects. To a great extent, flexibility depends on the firm having some excess capacity, or slack. For example, to increase production when demand increases, a manufacturing firm needs to have some excess production capacity in its plants; and, to take advantage of new investment opportunities, a firm needs unused financial resources. This need for excess capacity applies at least as much to its people as it does to its physical plant or its financial resources. Even if the firm has the physical and financial resources, its ability to make productive use of those resources will be constrained by its human resources. Simply put, it needs people to implement its plans, expansions, and investments, particularly in the increasingly service and information-dominated economies around the world. Consequently, it may be advantageous to maintain human resources even in slower periods to support flexibility. We will have more to say about the virtues of employment stability in chapter 6.

aA standard measure of the financial performance of a firm is ROA, measured as operating income before depreciation, interest, and taxes divided by total assets. Any changes in the firm’s performance that result from employment downsizing should show up in this measure.